Borderline cuisine

“Cocktail Teaser” (oil on canvas), by Boston-based artist Campbell-Lynn McLean, in her show “Acquired Tastes,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Feb 2.

David Sterling Brown: Of Trump and Richard III

Earliest surviving portrait of Richard III, from circa 1520.

HARTFORD

Written around 1592, William Shakespeare’s play “Richard III” follows the reign of England’s infamous monarch and charts the path of a charismatic, cunning figure.

As Shakespeare depicts the king’s reign, from June 1483 to August 1485, Richard III’s kingdom was wrought with chaos, confusion and corruption that fueled civil conflict in England.

As a scholar of Shakespeare, I first thought about Richard III and his similarities with Donald Trump after the latter’s debate with President Joe Biden in June 2024. Those similarities – and Shakespeare’s depictions – became even clearer after Trump’s election in November 2024.

Shakespeare’s play highlights the flawed character of a man who wanted to be, in modern terms, a dictator, someone who could do whatever he pleased without any consequences.\

In his 1964 essay, “Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare,” writer James Baldwin concluded that Shakespeare found poetry “in the lives of people” by knowing “that whatever was happening to anyone was happening to him.”

“It is said that Shakespeare’s time was easier than ours, but I doubt it,” Baldwin wrote. “No time can be easy if one is living through it.”

An undated portrait of Richard III. Universal History Archive/Getty Images?

In Act 2, Scene 3 of Shakespeare’s play, a common citizen says Richard is “full of danger.”

“Woe to the land that’s govern’d by a child,” the citizen further warned.

Beyond hiring murderers to kill his own brother, Shakespeare’s Richard was keen on belittling and distancing himself from people whom he viewed as being not loyal or being in his way – including his wife, Anne.

To clear the way for him to marry his brother’s daughter – his niece Elizabeth – Richard spread what now would be called fake news. In the play, he tells his loyalists “to rumor it abroad that Anne, my wife, is very grievously sick” and “likely to die.”

Richard then poetically reveals her death: “Anne my wife hath bid this world goodnight.”

Yet, before her death, Anne has a sad realization: “Never yet one hour in Richard’s bed / Did I enjoy the golden dew of sleep.”

That sentiment is echoed by Richard’s mother, the Duchess of York, who regrets not strangling “damned” Richard while he was in her “accursed womb.”

As Shakespeare depicts him, Richard III was a self-centered political figure who first appears alone on stage, determined to prove himself a villain.

In Richard’s opening speech, he even says that in order to become king, he will manipulate his own brothers George, the Duke of Clarence, and King Edward IV, “in deadly hate, the one against the other.”

But as his villainous crimes mount up, Richard shares a rare moment of self-awareness: “But I am in / So far in blood that sin will pluck on sin.”

Shakespeare’s Richard III and Trump

While the details of Trump’s and Richard’s lives differ in many ways, there are some similarities.

Much like Trump during his first term, Shakespeare’s Richard did not lead with morals, ethics or integrity.

Richard lied compulsively to everyone, as his soliloquys that contain his innermost thoughts make clear.

An illustration of English writer William Shakespeare (circa 1600). Rischgitz/Getty Images

Like Trump, Richard used empty rhetoric to persuade people with “sugared words” – he was not interested in speaking or promoting truth.

Moreover, Shakespeare’s Richard was a sexist and misogynist who verbally and physically disrespected women, including his wife and mother.

In the play, for example, Richard calls Queen Margaret, widow of King Henry VI, a “foul wrinkled witch” and a “hateful withered hag,” thus disparaging her older age.

He refers to Queen Elizabeth, wife of Edward IV, as a “damned strumpet” or prostitute, which she wasn’t.

Additionally, in order to cast doubts on his nephews’ legitimate claims to the throne, Richard spread false rumors about his mother, claiming that she was unfaithful.

Kamala Harris shakes hands with Donald Trump before their debate. AP Photo/Alex Brandon

For his part, Trump has no shortage of disparaging remarks about women. He once called his Democratic presidential rival Hillary Clinton “the devil” and characterized former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi as “crazy.”

Trump repeatedly peppered Vice President Kamala Harris during the presidential campaign with sexist and racists attacks.

He initially refused to pronounce her name correctly and openly mocked her racial identity as a Black woman, even questioning her “Blackness.”

A new day?

Like Trump, Richard III used religion to manipulate and confuse public perception of his amoral image.

In the play, Richard stages the equivalent of a modern-day photo op, standing between two “churchmen” with a “prayer-book” in his hands.

Much like Richard, Trump has courted evangelicals and used organized religion to his political advantage, most publicly by selling a “God Bless the USA Bible.”

Trump’s 2020 photo op in front of St. John’s Church in Washington is another example. It occurred during protests over the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man killed by a white police officer. Police in riot gear used tear gas to force protesters away from the White House; then Trump was escorted to the nearby church along with several administration officials.

As a political leader, Richard III left a legacy in English history as one of England’s worst monarchs.

That legacy includes his decisive defeat in the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 that led to his death and to a new era for England under King Henry VII.

After winning the throne, the new king offered a message of hope that suggested England would one day emerge from its time of civil discord:

Let them not live to taste this land’s increase That would with treason wound this fair land’s peace!

Now civil wounds are stopped, peace lives again. That she may long live here, God say amen.

David Sterling Brown is an associate professor of English at Trinity College in Hartford.

He receives funding from the Mellon Foundation and American Council of Learned Societies.

In the dim

“Edge of the Pond” (oil on canvas) (circa 1910), by Robertson Kirtland Mygatt, in the show ‘“Dawn and Dusk: Tonalism in Connecticut,’’ at Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum opening Jan. 17.

Jokes between strips

“The Naked i, one of the old Boston Combat Zone's larger strip clubs.’’

— Photo by Peter Vanderwarker

“Back in Boston, I discovered the great starting ground for so many comics: strip clubs! Since the early days of burlesque, these places always had a guy come out and tell jokes between every dancer’s turn onstage. I guess it was supposed to break the horrible monopoly of ogling bare flesh.’’

Jay Leno (born 1950), American TV host and comedian. He grew up in Andover, Mass.

Llewellyn King: My frightening, splendid Christmas in a Rhode Island emergency room

Photo by Peachyeung316

WEST WARICK, R.I.

Most people have horror stories about emergency rooms. Whether it is in Boston, Washington or Los Angeles, the stories are appalling.

Gurneys, sometimes with critically ill patients, lined up and left unattended along walls. Hurting people waiting for hours because of a shortage of staff, a shortage of beds, and a prevailing shortage of resources. Systems that are stressed and seem to be near breaking point.

Well, I have a story about my recent ER visit, which was pure joy and likely saved my life.

The story begins just before Christmas with my travels on crowded Amtrak trains and even more crowded airplanes.

I was wearing a mask during these trips, and had gotten flu and Covid shots, but I caught the flu. I received prompt and proper treatment for it, but I wasn’t licking it.

The Saturday before Christmas, early in the morning, I was having a fever hallucination: I sat bolt upright in bed and told my wonderful wife, Linda Gasparello, that I was preparing my maiden speech to the British House of Commons.

As I haven't set foot in the U.K. parliament for years, and then only in the press gallery, this insane bravado led her to call an ambulance at around 2 a.m. — over my protests that I was getting better, and taking a Tylenol would take care of everything. “Just you see,” I said.

What Linda saw was a very sick man clearly delirious and in need of urgent medical help.

Kindly men from the West Warwick, Rhode Island Fire Department’s ambulance service quietly entered our apartment and wafted me into the ambulance, where they checked my vital signs, did an electrocardiogram, and other work. I was in good, strong, comforting and knowledgeable hands.

When they were done, they drove me a few miles to Kent Hospital, part of Care New England, which has the second-busiest ER in the state. Not auspicious? Read on.

I wasn’t parked along a wall or interrogated about my insurance, but rushed straight to waiting nurses and the emergency medical technicians stood by until I was hooked up to an IV and a doctor had seen me. Shortly afterward, I was seen by two doctors.

Emergency rooms are, by all accounts, hellholes. I expected the worst, but I got two days of excellent care and pleasant attention. I have stayed at some of the best hotels in the world, including the Carlyle, in New York, the Ritz, in Paris, the Hassler, in Rome, and Brown’s, in London, and I had the same feeling of wellbeing at the Kent Hospital ER — people who cared and told me they were just a bell-ring away.

When my vitals were stable in a couple of days, I was invited to participate in a unique and remarkable system called “Kent Hospital at Home.”

Under this system (some form of which is operational at nearly 400 hospitals in 39 states), select patients can go home without being discharged, and the home becomes a hospital room. You are hooked up with a monitor, which sends data about your vitals to ER nurses. You can read these on an iPad, which also has contact information for the nurses and doctors assigned to you. You also get an emergency alarm on a wristband.

Everything the patient might have needed in the hospital is transported to the home. This might include an IV, oxygen, and other necessary equipment that might be used in the ER.

Best of all, you get visits twice a day by a nurse and once a day from a physician, either in person or virtual. I was in the system for just two days before discharge and saw the doctor in my home once and on Zoom once. I was given his cell phone number with instructions to call whenever I needed to.

The hospital-at-home concept was pioneered by the Mayo Clinic, among other medical facilities, during the Covid-19 pandemic. It has a waiver from Medicare, which means that you are billed as an in-hospitable patient not an outpatient.

Kent Hospital emphasized that when they moved me from the hospital to my home — in their vehicle — it was a “transfer” not in any way a discharge.

Research suggests that hospital-at-home care saves the provider between 19 percent and 30 percent on keeping the same patient in the hospital.

I am grateful to all who played a role in my recovery, from the ambulance crew to the emergency nurses, doctors, radiologists and porters.

Also, I am grateful for an insight into how medicine should work and how it will be enhanced in the future through technology of the kind that makes hospital-at-home care possible and viable.

For the record, I had Influenza A and sepsis pneumonia.

I had magnificent treatment and thank all who handed me a Christmas present beyond value. And I even saw a doctor making a house call. I wasn’t hallucinating.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. and he’s based in Rhode Island.

The cold fends them off

“I am lingering in Maine this winter, to fight wolves and foxes. The sun is less strong than Florida’s, but so is the spirit of development.’’

— Essayist and children’s book author E.B. White (1899-1985), in “A Report in January’’ (1958). He lived for many years on a farm in Brooklin, Maine.

Dressed for hydraulics

“Flood Drought Sisters,’’ by Cori Champagne, in her show “Water Mgmt,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery through Jan. 26.

Edited from commentary by the gallery:

“Cori Champagne's exhibition features a new series of functional garments addressing our most precious resource. Intended to navigate shifting hydrological cycles, Champagne’s hand-made clothing resembles streetwear, but is designed to collect, store and distribute water in preparation for a changing eco-future.

“At the center of the exhibition, ‘Flood Drought Sisters’ posits the extremes of floods and droughts in a more advantageous relationship to one another. The exquisitely crafted rainwear for Champagne’s ‘Flood’

ensemble gathers rainwater into a series of funnel-like flower forms protruding from the back and shoulders. Collected in modular containers, the rainwater can then be transferred, transported, and utilized via the wearable storage provided by the complementary ‘Drought’ garment. The two figures face each other, inviting viewers to appreciate various details in their creation, including the upcycling of ExxonMobil coveralls in the ‘Flood’ vest. A short video expands on the narrative. Shot with the artist in multiple locations, it further illustrates the symbiotic nature of both sides of the piece.

Llewellyn King: Trump’s law-of-the-jungle approach to foreign policy

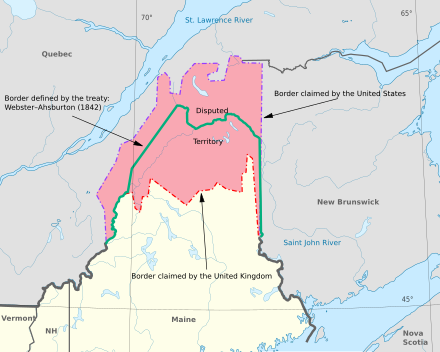

Map shows how the U.S.-British Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 resolved a border dispute that had threatened to to lead to war.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When Donald Trump began his first term as president, in 2017, I wrote that he came to office not as a politician who had won an election, but rather as a businessman who had won a takeover battle and was ready to hire, fire, sell-off, and generally to reshape the property he had bought.

On Christmas Day, Trump – with a series of posts on social media — revealed himself as a businessman who believes not that he has won the nation in a takeover battle, but rather that he has won the whole world and that he is ready to hire, fire and sell-off.

Also, like a canny takeover artist, he didn’t reveal his hand during the takeover struggle. During the election, there was no assertion from him that Canada should become the U.S. 51st state, that Panama was overcharging U.S. shipping or that ownership of Greenland was essential over and above the key role it already plays with a vital U.S. base, happily provided for by treaty with Denmark.

Like a businessman, Trump offered to buy Greenland during his first presidential term. His offer was soundly and summarily rejected. Now he is back and the answer hasn’t changed.

Canada, Trump believes, takes unfair advantage of the United States in trade, although the regime of the flourishing cross-border trading is the selfsame one: the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, signed in July 2020 by Trump himself as a vast improvement over its predecessor, the North American Free Trade Agreement, although in substance and spirit it is very similar.

When it comes to Panama, Trump has a double accusation. Beyond the belief that Panama is ripping us off, this kind of national business paranoia is part of the Trump manual of expectations in foreign policy: All foreign governments are scalawags bent on cheating America.

It is part of a kind of permanent, low-grade C-Suite paranoia that is present in many companies: Who is stealing an advantage, who is going to concede to the unions, who is angling for more shelf space, etc. You might call it corporate situational awareness paranoia.

Statesmanship is learned; good instincts help, but it isn't intuitive for most leaders. It is learned through studying history, meeting, talking, traveling, and moving in foreign policy circles. It is learned best on the job, if the job is in the House or the Senate.

Trump has learned not in that world, but in the world of New York real estate with its own jungle law — deals are done, undone, litigated, and political influence is brought to bear. Ultimately, there is victory for one side.

Trump correctly — and it could be said belatedly because he took no action during his first administration — has cast a penetrating light on China in the Americas. Trump has erroneously said that China runs the Panama Canal. No, Panama does. A subsidiary of Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison Holdings manages two ports at the canal's entrances, with Chinese firms providing more than $1 billion for the construction of a new bridge over the canal.

Panama’s revenues are up as a result of congestion charging, but fewer ships are transiting the canal due to drought. The vast Lake Gatun, which feeds the canal and keeps the lock system viable, is only partially full. The less water available, the fewer transits are possible. These dipped from 38 large ships to just 22 but rains have recently improved the situation and transits have risen.

Seizing canals is a fraught business, witness the disaster of France and Britain trying to seize the Suez Canal in 1956. Major damage to the Panama Canal would cost the United States for decades. It is a masterpiece of big, intricate engineering. I took a cruise through it for the purpose of understanding it better.

The British word “gobsmacked” is easily understood: smacked in the mouth. That is what happened to the commentariat — those who comment on national affairs. Trump’s Christmas Day declarations on Truth Social, his social-media network, went almost unmentioned. The reporting was there, the networks and newspapers turned up the volume, but the commentators were silent,

That, in its way, is as notable as Trump’s implication that he has bought the world and plans to take possession. We, the opinion writers, have been struck dumb, you might say. That is news in itself.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

White House Chronicle

James B. Rebitzer: Market concentration by CVS and other PBM’s helps boost drug prices

BOSTON

Wegovy and Ozempic are weight-loss drugs that promise to transform the treatment of obesity, heart disease and other chronic conditions that afflict millions of Americans. But while everyone agrees these drugs have the potential to transform lives, no one can agree on how best to pay for them.

Wegovy sells for a list price – or price before discounts – of $1,349 per month in the U.S. The same drug lists for $265 in Canada and less than half of that in the U.K. These dramatic differences illustrate a larger issue: The list price of patented drugs in the U.S. are far higher than in other rich countries.

U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont) spoke for many Americans when he said the high cost of drugs in America was “not just an issue of economics” but rather “a profound moral issue.”

Moral outrage leads to a search for villains. Joe Kernan, host of CNBC’s business show Squawk Box, cut to the chase when he asked: “Who is screwing us here? The PBMs? The drugmakers?”

As a health economist who writes about innovations in the health sector, I have spent a good portion of the past five years thinking about these questions. What I’ve learned is that high list prices for drugs don’t tell us much about who is screwing whom. To truly understand the problem of drug pricing in the U.S., you need to start with the tricky economics of the PBMs, or pharmacy benefit managers.

Pharmacy benefit managers started popping up in the late 1960s as providers of claims processing and administrative services for health insurers. Over time, they became essential middlemen between drugmakers and the many insurers, employers and government entities who purchase drugs on behalf of their members, constituents and beneficiaries.

Mergers between PBMs have led to a market dominated by a small number of very large players. In 2023, the three biggest ones – OptumRx, Express Scripts and CVS Caremark – managed 79% of U.S. prescription claims and served roughly 270 million customers. (CVS is based in Woonsocket, R.I.)

The primary role of these companies is to negotiate price, affordability and access to prescription drugs. They do this by operating and designing formularies, which are lists of drugs that insurers cover.

A drug’s listing on a formulary determines its price. Joe Buglewicz/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Formularies also assign drugs to different tiers that determine what patients must pay out of pocket to access the drug. Generic drugs are typically placed in the tier with the lowest out-of-pocket costs. Patented drugs that insurers prefer are placed in a tier with higher costs, and nonpreferred drugs are in a tier that requires patients to pay even more. Some drugs can even be excluded from the formulary altogether, meaning insurance won’t cover them.

Tier placement determines how affordable a medication is to consumers and the effective drug price that insurers pay. Drugmakers compete with each other for placement on desired formulary tiers by offering PBMs significant discounts off their list price. The price at which the PBM obtains the drug for its clients is the net price – the list price minus the drugmaker’s discount.

If a drugmaker increases its rebate, the net price falls, even if the publicly posted list prices remain high. This is why focusing on list prices to determine the cost of a drug can be misleading.

The price is right?

List prices for drugs are public knowledge, but drugmakers’ discounts to PBMs are closely held secrets. As a result, it’s hard to know exactly how much insurers pay for most prescription drugs.

This secrecy raises challenging questions. Do PBMs use their size and negotiating power to win lower net prices from drugmakers? Or do PBMs use their dominant market position and opaque business practices to enrich themselves at the expense of their customers and the rest of society?

The answer to both these questions is, surprisingly, yes. If the contest for formulary placement works as it should, competition compels drugmakers to offer substantial discounts off the published list price. As a result, insurers and consumers benefit from a reduced net price for drugs. However, formulary competition can be undermined in various ways.

In a 2024 report, for example, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission found evidence that the manufacturer of a patented form of insulin offered higher rebates to a PBM if competing insulins were placed on a less favorable tier of a formulary or excluded altogether. This arrangement reduces consumer choice. If a cheaper generic equivalent is excluded, the arrangement would also favor a more expensive drug that raises patient costs. Widespread use of such exclusionary rebates might even discourage new generics and reduce competition.

Introducing biosimilar drugs manufactured specifically for PBMs to substitute for expensive biologics manufactured elsewhere can also undermine formulary competition. When PBMs favor their in-house products in formularies, this reduces the incentive for other drugmakers to introduce competing products. The result is both less competition and higher prices.

Competition within the formulary can also be distorted when drugmakers post very high list prices. This artificially inflates rebates for PBMs without lowering net prices for insurers and other parties. Inflated list prices also increase the cost of drugs for some groups of patients – notably, people who lack health insurance or have high deductible plans.

Market competition

Just as fair competition can break down within the PBM’s formulary, it can also fall apart in the market for PBM services.

The current regulatory environment in the U.S. tolerates overly large PBMs that engage in anticompetitive practices to accumulate excessive profits. Without strong competitors, dominant PBMs are free to charge their customers high fees and keep a larger portion of drugmaker rebates for themselves.

In theory, this problem should be self-correcting. High profits should attract new competitors into the industry. Competition from these entrants should lower fees and reduce the fraction of rebates these companies keep. However, things work out differently in practice because the largest PBMs have merged with the largest health insurers. CVS has merged with Aetna. Express Scripts and OptumRx merged, respectively, with Cigna and UnitedHealthcare. These combinations reduce the number of potential customers for new PBMs and so keep new competitors from entering the market.

CVS Health has its own PBM (CVS Caremark), pharmacy chain (CVS Pharmacy) and health insurer (Aetna). Charles Krupa/AP Photo

Scrappy upstarts that could shake up the status quo also find themselves at a disadvantage due to common contracting practices. Large PBMs, for example, often insist on “most-favored-nation” contracts that require drugmakers to meet or beat the prices they offer to other buyers. These contracts eliminate the competitive advantage a new PBM might gain from obtaining better prices than incumbent companies.

There is growing concern among experts that dominant PBMs also use formularies to steer profitable “specialty prescriptions” to pharmacies with whom they are affiliated. The pharmacies affiliated with the three biggest PBMs expanded their share of the specialty drug market from 55% to 67% between 2016 and 2023. Concerns over such anticompetitive practices have led to bipartisan legislation to force PBMs to sell off their retail or mail-order pharmacies.

Who are the villains?

So, are PBMs screwing us? If we didn’t have PBMs, we would need to invent them – or something like them – to obtain reasonable prices on patented drugs. But the concentration of market power among a few companies threatens to dissipate the value they create.

Increasing competition within the PBM marketplace will likely require a larger number of smaller PBMs, and large insurers may also be required to divest their PBM units.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, smaller PBMs will likely be just as able to negotiate a low net price for Wegovy and other patented drugs as larger PBMs. Beyond a certain minimum scale, it is competition for formulary placement, not PBM size, that matters. A more competitive and transparent market for PBM services will help keep that contest fair and transparent – to the benefit of customers and society.

In that sense, PBMs aren’t the villain. Too much market power in too few hands is the problem, and that’s something more competition, sensible regulation and vocal consumers might fix.

James B. Rebitzer is Wexler Professor of Management, Economics and Public Policy at Boston University

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Chris Powell: Minimizing college arrogance, hypocrisy; take on liquor-store lobby

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Gov. Ned Lamont is right that the expense-account exploitation perpetrated by the chancellor of the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities system, Terrence Cheng, and his fellow top administrators is "small ball," insofar as the financial expense goes. It doesn't compare to the hundreds of millions of dollars in cost overruns incurred in the New London state pier project by the Connecticut Port Authority, which haven't offended the governor either.

Even so, there is much to be offended about in the CSCU system, and it goes beyond Cheng's awarding himself the perks of royalty on top of a salary and benefit package worth a half million dollars annually while constantly pleading poverty for the higher education system, which chronically operates at a deficit and is always asking for more money.

Cheng's arrogance and hypocrisy are not "small ball" but major-league.

So is the unaccountability of the college system, which is supposed to answer to its 15-member Board of Regents. While the board includes former state House Speaker Richard J. Balducci, a Democrat, and New Britain Mayor Erin Stewart, a Republican who may run for governor, it did not rush to investigate when Connecticut's Hearst newspapers exposed Cheng's exploitation of his expense account. Instead the governor had to ask state Comptroller Sean Scanlon to investigate, apparently assuming that the Board of Regents is just for show and its members are airheads. (The governor might know, since most of the regents are his appointees.)

The regents have escaped critical questioning not just by the governor and the comptroller but also by news organizations covering the expense-account scandal. How did the regents fail to learn how Cheng and his gang were abusing their expense accounts while pleading the college system's poverty? If Cheng and his gang weren't reporting to the regents, to whom were they reporting? Who was supposed to supervise their expense claims? Apparently no one.

How do the regents justify the half million dollars in compensation conferred on Cheng every year? What is so special about his leadership? Why do they continue to let Cheng live out of state, far from his workplace? What do the regents think about the example Cheng gang has set?

The regents are off the hook until someone bothers to ask.

Having decided to minimize the scandal, the governor probably won't be asking.

The leaders of the Republican minority in the General Assembly, Sen. Stephen Harding, of Brookfield, and Rep. Vincent J. Candelora, of North Branford, declared that Cheng should be fired, but Democratic legislators said only that they'd welcome proposals for tighter standards for purchases by college administrators. The arrogance, hypocrisy and bad examples of the administrators seem not to bother the Democratic legislators any more than they bother the governor.

During the legislature's budget deliberations in a few weeks will the Democrats even remember the high living of the Cheng gang when they show up again to ask for more money?

BREAK THE LIQUOR LOBBY: When the legislature convenes next month Connecticut's supermarkets again may ask to be allowed to sell wine along with the beer they already sell. Most state residents would like the convenience, which is enjoyed in 42 other states. Again the problem will be the liquor stores and particularly the "mom and pop" stores, which fear that ordinary free-market competition will put them out of business.

So what if it does? Supermarkets and other retailers in Connecticut fail and close all the time and no legislators propose to restrict competition in those businesses. But the liquor stores purport to be special and to deserve protection against competition. They get this protection not only through the ban on supermarket sales of wine but also through the state's grotesque system of minimum prices for alcoholic beverages, which assures retailers a profit and customers high prices.

Most legislative districts have at least several "mom and pops" and statewide they form a powerful lobby against the public interest in more competition and lower prices. Will legislators dare to stand up against this special interest next year?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Hatchlings’ show brightens Boston’s winter

“Hatchlings’’ at Boston’s Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway.

Edited from a Boston Guardian report by Brandon Hill

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

“Hatchlings,’’ Boston’s captivating winter lights installation created by interdisciplinary design team Studio HHH first graced The Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway last winter, lighting up the park with vibrant, animated arches that offer a playful nod to one of Boston’s most iconic landmarks, the Hatch Shell on the Esplanade.

“Hatchlings” brings to life the whimsical idea of the Hatch Shell "hatching" a series of baby shells that wander off along the Greenway like a multicolored parade of ducklings. This year, the installations have expanded from seven to nine mini-Hatch Shell structures scattered across the park, including a new arrangement of three “Hatchlings’’ in a single space, creating a primary destination for visitors near the summer site of the Trillium Beer Garden. The smallest measures 2.5 feet, while the largest reaches 8.5 feet tall. The bright, joyful display invites visitors to engage with the park in a new way, serving as an interactive photo backdrop and a perfect spot for informal gatherings.

“We really loved the challenge of creating an experience specific to Boston’s identity,” said Vanessa Till Hooper, founder and creative director of Studio HHH.

“The Hatch Shell design has these wood baffles that bounce the sound from the stage out into the grassy area in front of it. Those angles are what we were replicating in the weaving of the lights to mimic those baffled angles. So, what you see in wood in the Hatch Shell is what you see in the lights in the “Hatchlings.”

Each “Hatchling” is powered by solar energy, a symbolic aspect of the artwork that functions as a model of smart implementation of solar energy even in the darker winter months. “Sustainability these days is so much about awareness and also proving that things are possible,” Till Hooper said. “It was a mission for us to prove that it was possible to do a winter lights installation that had a solar element and really showcasing it as an opportunity for other people to consider the use of solar in their holiday lights.”

This year’s setup is about 50/50 solar and hybrid energy. With some of the installations relying entirely on solar energy, some entirely on the grid, but mostly a hybrid mix.

Initially, the “Hatchlings” were intended to be small performance spaces to book live music or throw impromptu performances, but the studio quickly learned last year that the public wanted to engage with the structures more directly. They moved performances to be adjacent to the ”Hatchlings,’’ opening up the structures as a collection of Boston’s brightest holiday photo backdrops.

The “Hatchlings” will remain on display until February.

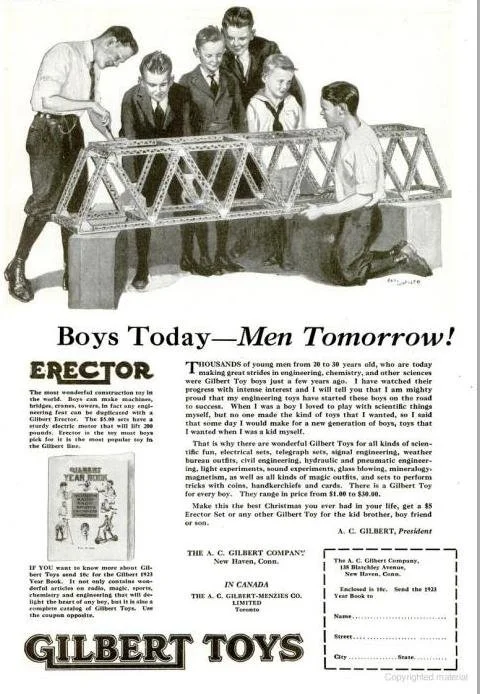

‘The toys did it’

Text from The New England Historical Society

“In 1918, America was at war. The country needed to devote all of its industrial might to victory in Europe. A war council considered banning all toy production and prohibiting gift-giving at Christmas. It took A.C. Gilbert, inventor of the Erector Set, to save Christmas.

“Gilbert led a remarkable life. He was a medical doctor, an Olympic gold medal winner, a magician, a toy millionaire, a big-game hunter and, most of all, a kid at heart.

“He wore old gabardine suits and rubber soled shoes, and he always carried a pipe that he sometimes stuck into his pocket while lit. In late October 1918, he brought a satchel full of educational toys to Washington, D.C., and let a room full of Cabinet secretaries play with them.

“He persuaded them that children needed toys because the nation needed scientists and engineers. The war council decided to give Santa free rein after all.

“‘The toys did it, Gilbert said.’’

It’s a living

“The Maine Lobsterman,’’ in Lobsterman Park, Portland. Standing at the intersection of Middle Street and Temple Street, it was sculpted by Victor Kahill.

“I conversed with a young lobster fisherman who gets up at 5 in the morning and goes home again from the sea at 3 in the afternoon. I asked him if he liked lobstering. ‘You get used to it’ was his reply.’’

—From Back Roads of New England (1974), by Earl Thollander

The white stuff

“Whispers of Winter” (oil on canvas), by Louie Pisterzi, in the “Let There Be Love’’ show at Spectrum Art Gallery, Centerbrook, Conn., through Jan. 11

William Morgan: Postcard of assignation?

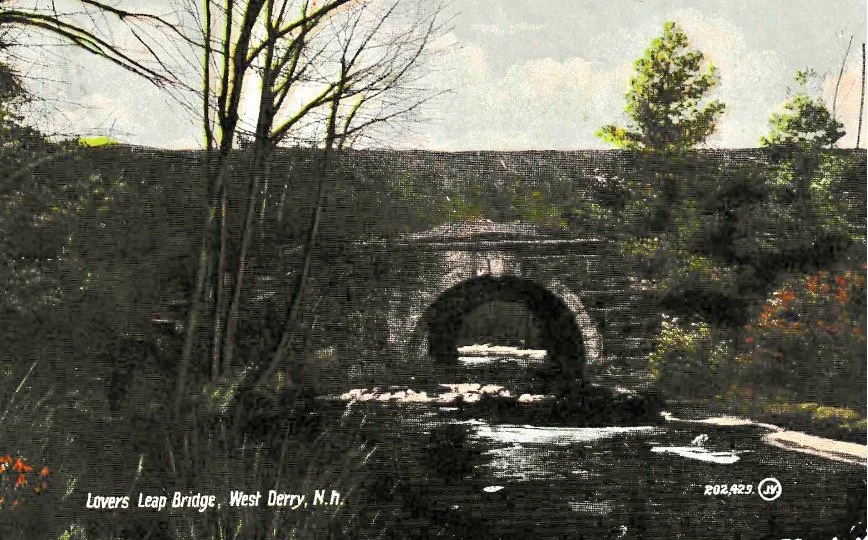

Unlike the usual old postcard finds, with their recitation of visiting the scene on the front of the missive, this one, sent 114 years ago to Fred P. McFarland in the New Hampshire town of Raymond, offers both a bit of mystery and a hint of romance. The unnamed sender, M.––––, got across quite a bit of information, along with the hint of a possible tryst. Compared to a contemporary Facebook post, an e-mail, or a text, the writer managed to convey considerable private meaning in a very public medium.

The attractive but hardly remarkable bridge depicted here is labeled Lovers Leap, while the one-cent stamp is attached upside down – in my day the inverted postage was used only on mail to girlfriends.

While chest-nutting is probably not a code for some other more physical activity, Miss M.––––suggests meeting at Lizzie Seavy’s for a husking bee. An article on husking bees in the Dakotas at the same period notes the beyond-harvest courting aspect of peeling corn stalks: a red ear of corn discovered by a girl could be a gift to her beau, but if a boy found a red ear, he was allowed to kiss the object of his affections. I would hesitate to speculate on the meaning of Fred’s “working hard.”

The seemingly forward and determined M.–––– was also confident in the postoffice’s ability to deliver her card by the next day, in time for Fred to decide if he wanted to go husking. Some postcards nowadays might take weeks to be delivered.

William Morgan is a Providence-based writer and photographer. As a chronicler of New England art, especially architecture, he has contributed to such publications at The Boston Globe, The Providence Journal, The Hartford Courant and The Portland Press-Herald

From the plain to the hills

The green area between the uplands — now the Connecticut River Valley — used to be a huge lake that formed about 15,000 years ago as the Ice Age receded.

Merry ink on paper

One of the first American Christmas cards, printed circa 1874. It was created by the Boston-based business of Louis Prang (1824-1909), Prussian-American printer, lithographer and publisher. He is sometimes called the "father of the American Christmas card.’’

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

The (physical) Christmas card tradition can sometimes be a bit weird. You get cards from people you haven’t actually seen in many years. Sometimes they’re accompanied by narratives presenting what’s been happening with relatives and close friends of the senders – often as folded inserts in the card envelopes with listings of achievements – graduations, fancy new jobs, prizes – and less so, sad news, especially of deaths and illness. Sometimes they’re weirdly intimate considering the length of time since you’ve seen or talked with the writers.

You might never again get a phone call or a visit from some of these senders. The next word you might get about them might be their obituaries.

My approach has always been to reply, in ink on paper, with a card to anyone who has taken the time to send one, no matter how long ago it was that I saw the senders. That’s not just because it’s courteous but because you never know what you might learn by maintaining these relationships, however tenuous they may seem. It’s a kind of yearly discipline, and you can look at the cards over the years as a kind of social history.

Some may complain about your handwriting (my arthritic hands too often produce a scrawl), but most people like the proof of personality and physicality, however flawed.

Block-sending Christmas cards by email can be a little chilly and sterile. But then, many people are fired by email and text these days. No wonder anomie is advancing.

How to make your rooms bigger

From the current show “The Art of French Wallpaper Design,’’ at the Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence.

Peter C. Mancall: Why the Puritans opposed Christmas

“The Puritan,’’ by Augustus Saint Gaudens, in Springfield, Mass.

‘When winter settles in across the U.S., the alleged “War on Christmas” heats up.

In recent years, department store greeters and Starbucks cups have sparked furor by wishing customers “happy holidays.” This year, with state officials warning of holiday gatherings becoming superspreader events in the midst of a pandemic, opponents of some public health measures to limit the spread of the pandemic are already casting them as attacks on the Christian holiday.

But debates about celebrating Christmas go back to the 17th Century. The Puritans, it turns out, were not too keen on the holiday. They first discouraged Yuletide festivities and later outright banned them.

At first glance, banning Christmas celebrations might seem like a natural extension of a stereotype of the Puritans as joyless and humorless that persists to this day.

But as a scholar who has written about the Puritans, I see their hostility toward holiday gaiety as less about their alleged asceticism and more about their desire to impose their will on the people of New England – Natives and immigrants alike.

The earliest documentary evidence for their aversion to celebrating Christmas dates back to 1621, when Gov. William Bradford of Plymouth Colony castigated some of the newcomers who chose to take the day off rather than work.

But why?

As a devout Protestant, Bradford did not dispute the divinity of Jesus Christ. Indeed, Puritans spent a great deal of time investigating their own and others’ souls because they were so committed to creating a godly community.

Bradford’s comments reflected Puritans’ lingering anxiety about the ways that Christmas had been celebrated in England. For generations, the holiday had been an occasion for riotous, sometimes violent behavior. The moralist pamphleteer Phillip Stubbes believed that Christmastime celebrations gave celebrants license “to do what they lust, and to folow what vanitie they will.” He complained about rampant “fooleries” like playing dice and cards and wearing masks.

Civil authorities had mostly accepted the practices because they understood that allowing some of the disenfranchised to blow off steam on a few days of the year tended to preserve an unequal social order. Let the poor think they are in control for a day or two, the logic went, and the rest of the year they will tend to their work without causing trouble.

English Puritans objected to accepting such practices because they feared any sign of disorder. They believed in predestination, which led them to search their own and others’ behavior for signs of saving grace. They could not tolerate public scandal, especially when attached to a religious moment.

Puritan efforts to crack down on Christmas revelries in England before 1620 had little impact. But once in North America, these seekers of religious freedom had control over the governments of New Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut.

Boston became the focal point of Puritan efforts to create a society where church and state reinforced each other.

The Puritans in Plymouth and Massachusetts used their authority to punish or banish those who did not share their views. For example, they exiled an Anglican lawyer named Thomas Morton who rejected Puritan theology, befriended local Indigenous people, danced around a maypole and sold guns to the Natives. He was, Bradford wrote, “the Lord of Misrule” – the archetype of a dangerous type who Puritans believed create mayhem, including at Christmas.

In the years that followed, the Puritans exiled others who disagreed with their religious views, including Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams who espoused beliefs deemed unacceptable by local church leaders. In 1659, they banished three Quakers who had arrived in 1656. When two of them, William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson, refused to leave, Massachusetts authorities executed them in Boston.

This was the context for which Massachusetts authorities outlawed Christmas celebrations in 1659. Even after the statute left the law books in 1681 during a reorganization of the colony, prominent theologians still despised holiday festivities.

In 1687, the minister Increase Mather, who believed that Christmas celebrations derived from the bacchanalian excesses of the Roman holiday Saturnalia, decried those consumed “in Revellings, in excess of wine, in mad mirth.”

The hostility of Puritan clerics to celebrations of Christmas should not be seen as evidence that they always hoped to stop joyous behavior. In 1673, Mather had called alcohol “a good creature of God” and had no objection to moderate drinking. Nor did Puritans have a negative view of sex.

What the Puritans did want was a society dominated by their views. This made them eager to convert Natives to Christianity, which they managed to do in some places. They tried to quash what they saw as usurious business practices within their community, and in Plymouth they executed a teenager who had sex with animals, the punishment prescribed by the Book of Leviticus. When the Puritans believed that Indigenous people might attack them or undermine their economy, they lashed out – most notoriously in 1637, when they set a Pequot village on fire, murdered those who tried to flee and sold captives into slavery.

By comparison to their treatment of Natives and fellow colonists who rebuffed their unbending vision, the Puritan campaign against Christmas seems tame. But it is a reminder of what can happen when the self-righteous control the levers of power in a society and seek to mold a world in their image.

Peter C. Mancall is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities at the University of Southern California.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

A taste for the foreign

“31 Flavors Invading Japan/Today’s Special,’’ by Masami Teraoka, in the show “Im/Perfect Modernisms: Asian Art and Identity Since 1945,’’at the Worcester Art Museum, through Jan. 20.

The museum says:

“Challenge your preconceptions of modern art through thought-provoking and at times subversive artworks created across postwar Asia.’’