Llewellyn King: Trying to censor stressed news media via lawsuits

Photojournalists and President Obama in 2014.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a lot of dither about the future of journalism. Make no mistake, it is an essential commodity.

If you know what is going on in Gaza, Ukraine or Syria, it is because brave journalists told you. Not the government, not some academic institution, not artificial intelligence, and not hearsay from your friends or from a political party.

The crisis in journalism isn’t that it failed analytically in last election, or that we — an irregular army of individualists — failed, but that journalism has run out of money and its political enemies have found that the courts (and the fear of libel prosecution) can terrorize the companies that own the media.

In 2016 the gossipy site, Gawker, was sued by the pro wrestler and political figure Hulk Hogan. The lawsuit was financed by the billionaire investor Peter Thiel.

Now come two suits, filed by President-elect Donald Trump: One which he won against ABC News, and one just filed against the Des Moines Register. It is reported that conservative interests plan a series of these legal interventions against the media.

This will have a frightening impact on news coverage. When there is fear of prosecution, there is less likely to be investigative news coverage.

So far, the most troublesome of the prosecutions has been the one against ABC News. The network caved in early. It agreed to pay $15 million plus legal fees into a fund for what will be the first Trump presidential library.

Could it be that ABC is owned by Disney, and Disney wants good relations with the incoming administration?

But a much bigger problem faces the media than the fear of prosecution. It is that the old media, led by local and regional newspapers, are dying and although there are thousands of podcasts, they don’t take up the slack.

You could listen to an awful lot of podcasts and not know what is going on. State houses and local courts aren’t being covered. The sanitizing effect of press surveillance has been withdrawn and, frankly, God help the poor defendants in a local court where there is a disproportionate desire to plead cases, to avoid honest trials even when there is conspicuous doubt.

I never tire of repeating what Dan Raviv, former CBS News correspondent, said to me once, “My job is simple. I try to find out what is going on and tell people.”

Quite so. But there is a problem: Journalism needs to be concentrated in a newspaper or a broadcast outlet where there is enough revenue to do the job. Otherwise, you get what I think of as the upside-down pyramid of more and more commentary, based on less and less reporting.

We are awash in commentary, some of it very good and some of it trash. But it is all based on news gathered by those news organizations that can afford to employ a phalanx of reporters.

Regional newspapers used to have their own Washington bureaus and their own foreign bureaus. At one time, The Baltimore Sun had 12 overseas bureaus. Now it has none.

This is the story across the country. Fewer people actually cover the news, digging, checking and telling us what they have found out.

Throughout the history of journalism, technology has been disruptive, sometimes advantageously and sometimes less so. Modern printing presses developed at the end of the 19th Century were important boosters, as was the invention of the Linotype machine, in 1884.

On the negative side, television killed off evening papers and podcasts are taking a toll on radio. Now the Internet and the tech companies — Google, Facebook, et al. — have siphoned off most of the revenue that supported newspapers, radio and television.

As one can’t have a free and fair society without vibrant journalism, we clearly need a new paradigm that is Internet-based news organizations that are large enough and rich enough to do the job in the time-honored way with reporters asking questions, whether it is at the courthouse, the White House, or on the battlefield.

There is a clear choice: News and informed analysis or rumor and conspiracy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Circle route

“Subtle and Strong” (steel), by Margaret Jacobs, in her show at 3S Artspace, Portsmouth, N.H. She develops organic textures and surfaces.

Market Square, Portsmouth, in 1853

Nicole Granucci: What is the universe expanding into?

HAMDEN, Conn.

When you bake a loaf of bread or a batch of muffins, you put the dough into a pan. As the dough bakes in the oven, it expands into the baking pan. Any chocolate chips or blueberries in the muffin batter become farther away from each other as the muffin batter expands.

The expansion of the universe is, in some ways, similar. But this analogy gets one thing wrong – while the dough expands into the baking pan, the universe doesn’t have anything to expand into. It just expands into itself.

The universe expands like a baking muffin. The objects in space move farther apart, with more space between them. UChicago Creative

It can feel like a brain teaser, but the universe is considered everything within the universe. In the expanding universe, there is no pan. Just dough. Even if there were a pan, it would be part of the universe and therefore it would expand with the pan.

Even for me, a teaching professor in physics and astronomy who has studied the universe for years, these ideas are hard to grasp. You don’t experience anything like this in your daily life. It’s like asking what direction is farther north of the North Pole.

Another way to think about the universe’s expansion is by thinking about how other galaxies are moving away from our galaxy, the Milky Way. Scientists know the universe is expanding because they can track other galaxies as they move away from ours. They define expansion using the rate that other galaxies move away from us. This definition allows them to imagine expansion without needing something to expand into.

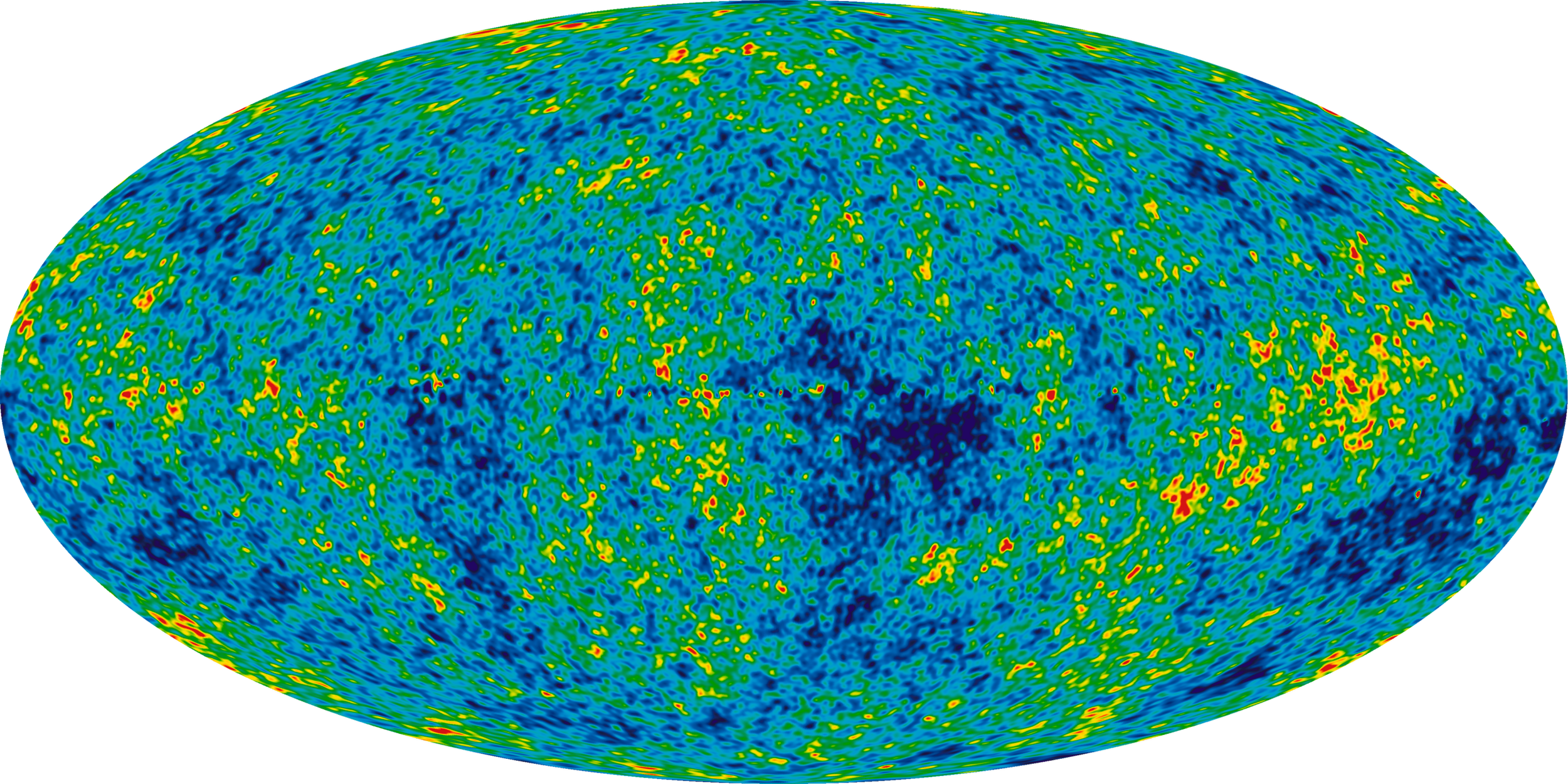

The expanding universe

The universe started with the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago. The Big Bang describes the origin of the universe as an extremely dense, hot singularity. This tiny point suddenly went through a rapid expansion called inflation, where every place in the universe expanded outward. But the name Big Bang is misleading. It wasn’t a giant explosion, as the name suggests, but a time where the universe expanded rapidly.

The universe then quickly condensed and cooled down, and it started making matter and light. Eventually, it evolved to what we know today as our universe.

The idea that our universe was not static and could be expanding or contracting was first published by the physicist Alexander Friedman in 1922. He confirmed mathematically that the universe is expanding.

While Friedman proved that the universe was expanding, at least in some spots, it was Edwin Hubble who looked deeper into the expansion rate. Many other scientists confirmed that other galaxies are moving away from the Milky Way, but in 1929, Hubble published his famous paper that confirmed the entire universe was expanding, and that the rate it’s expanding at is increasing.

This discovery continues to puzzle astrophysicists. What phenomenon allows the universe to overcome the force of gravity keeping it together while also expanding by pulling objects in the universe apart? And on top of all that, its expansion rate is speeding up over time.

Many scientists use a visual called the expansion funnel to describe how the universe’s expansion has sped up since the Big Bang. Imagine a deep funnel with a wide brim. The left side of the funnel – the narrow end – represents the beginning of the universe. As you move toward the right, you are moving forward in time. The cone widening represents the universe’s expansion.

The expansion funnel visually shows how the universe’s rate of expansion has increased over time. At the left of the funnel is the Big Bang, and since then, the universe has expanded at a faster and faster rate. NASA

Scientists haven’t been able to directly measure where the energy causing this accelerating expansion comes from. They haven’t been able to detect it or measure it. Because they can’t see or directly measure this type of energy, they call it dark energy.

According to researchers’ models, dark energy must be the most common form of energy in the universe, making up about 68% of the total energy in the universe. The energy from everyday matter, which makes up the Earth, the Sun and everything we can see, accounts for only about 5% of all energy.

Dark matter and dark energy make up most of the universe. Green Bank Observatory, CC BY-NC-ND

Outside the expansion funnel

So, what is outside the expansion funnel?

Scientists don’t have evidence of anything beyond our known universe. However, some predict that there could be multiple universes. A model that includes multiple universes could fix some of the problems scientists encounter with the current models of our universe.

One major problem with our current physics is that researchers can’t integrate quantum mechanics, which describes how physics works on a very small scale, and gravity, which governs large-scale physics.

The rules for how matter behaves at the small scale depend on probability and quantized, or fixed, amounts of energy. At this scale, objects can come into and pop out of existence. Matter can behave as a wave. The quantum world is very different from how we see the world.

At large scales, which physicists call classical mechanics, objects behave how we expect them to behave on a day-to-day basis. Objects are not quantized and can have continuous amounts of energy. Objects do not pop in and out of existence.

The quantum world behaves kind of like a light switch, where energy has only an on-off option. The world we see and interact with behaves like a dimmer switch, allowing for all levels of energy.

But researchers run into problems when they try to study gravity at the quantum level. At the small scale, physicists would have to assume gravity is quantized. But the research many of them have conducted doesn’t support that idea.

An infinitely expanding universe lies beyond the Milky Way galaxy. DECaPS2/DOE/FNAL/DECam/CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, M. Zamani & D. de Martin via AP

One way to make these theories work together is the multiverse theory. There are many theories that look beyond our current universe to explain how gravity and the quantum world work together. Some of the leading theories include string theory, brane cosmology, loop quantum theory and many others.

Regardless, the universe will continue to expand, with the distance between the Milky Way and most other galaxies getting longer over time.

Nicole Granucci is a physics instructor at Quinnipac University, in Hamden, Conn.

She does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.

Martha Bebinger: Boston hospital turns to solar to help patients pay utility bills

Moakley Building at Boston Medical Center from Harrison Avenue

Drknchkn photo

Text from Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

BOSTON

Anna Goldman, a primary-care physician at Boston Medical Center, got tired of hearing that her patients couldn’t afford the electricity needed to run breathing-assistance machines, recharge wheelchairs, turn on air conditioning, or keep their refrigerators plugged in. So she worked with her hospital on a solution.

The result is a pilot effort called the Clean Power Prescription program. The initiative aims to help keep the lights on for roughly 80 patients with complex, chronic medical needs.

The program relies on 519 solar panels installed on the roof of one of the hospital’s office buildings. Half the energy generated by the panels helps power the medical center. The rest goes to patients who receive a monthly credit of about $50 on their utility bills.

Kiki Polk was among the first recipients. She has a history of Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure.

On a warm fall day, Polk, who was nine months pregnant at the time, leaned into the air-conditioning window unit in her living room.

“Oh my gosh, this feels so good, baby,” Polk crooned, swaying back and forth. “This is my best friend and my worst enemy.”

An enemy, because Polk can’t afford to run the AC. On cooler days, she has used a fan or opened a window instead. Polk knew the risks of overheating during pregnancy, including added stress on the pregnant person’s heart and potential risks to the fetus. She also has a teenage daughter who uses the AC in her bedroom — too much, according to her mom.

Kiki Polk, one of the first Boston Medical Center patients to enroll in the Clean Power Prescription program, turns on the air conditioner in her home in the city’s Dorchester neighborhood. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Polk got behind on her utility bill. Eversource, her electricity provider, worked with her on a payment plan. But the bills were still high for Polk, who works as a school-bus and lunchroom monitor. She was surprised when staff at Boston Medical Center, where she was a patient, offered to help.

“I always think they’re only there for, you know, medical stuff,” Polk said, “not the personal financial stuff.”

Polk is on maternity leave now to care for her baby, the tiny Briana Moore.

Goldman, who is also BMC’s medical director of climate and sustainability, said hospital screening questionnaires show thousands of patients like Polk struggle to pay their utility bills.

“I had a conversation recently with someone who had a hospital bed at home,” Goldman said. “They were using so much energy because of the hospital bed that they were facing a utility shut-off.”

Goldman wrote a letter to the utility company requesting that the power stay on. Last year, she and her colleagues at Boston Medical Center wrote 1,674 letters to utility companies asking them to keep patients’ gas or electricity running. Goldman took that number to Bob Biggio, the hospital’s chief sustainability and real estate officer. He’d been counting on the solar panels to help the hospital shift to renewable energy, but sharing the power with patients felt as if it fit the health system’s mission.\

“Boston Medical Center’s been focused on lower-income communities and trying to change their health outcomes for over 100 years,” Biggio said. “So this just seemed like the right thing to do.”

Standing on the roof amid the solar panels, Goldman pointed out a large vegetable garden one floor down.

“We’re actually growing food for our patients,” she said. “And, similarly, now we are producing electricity for our patients as a way to address all of the factors that can contribute to health outcomes.”

Many hospitals help patients sign up for electricity or heating assistance because research shows that not having them increases respiratory problems, mental distress and makes it harder to sleep. Aparna Bole, a pediatrician and senior consultant in the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity at the federal Department of Health and Human Services, said these are common problems for low- and moderate-income patients. BMC’s approach to solving them may be the first of its kind, she said.

“To be able to connect those very patients with clean, renewable energy in such a way that reduces their utility bills is really groundbreaking,” Bole said.

Bole is using a case study on the solar credits program to show other hospitals how they might do something similar. Boston Medical Center officials estimate the project cost $1.6 million, and said 60% of the funding came from the federal Inflation Reduction Act. Biggio has already mapped plans for an additional $11 million in solar installations.

“Our goal is to scale this pilot and help a lot more patients,” he said.

The expansion he envisions would allow a tenfold increase in patients who could be served by the program, but it still would not meet the demand. For now, each patient in the pilot program receives assistance for just one year. Boston Medical Center is looking for partners who might want to share their solar energy with the hospital’s patients in exchange for a higher federal tax credit or reimbursement.

Eversource’s vice president for energy efficiency, Tilak Subrahmanian, said the pilot was a complex project to launch, but now that it’s in place, it could be expanded.

“If other institutions are willing to step up, we’ll figure it out,” Subrahmanian said, “because there is such a need.”

Martha Bebinger is a WBUR reporter

This article is from a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR, and KFF Health News.

Martha Bebinger, WBUR: marthab@wbur.org, @mbebinger

Where I became an American

In Faneuil Hall

“I became an American on Nov. 4, 2010, at an elegant ceremony in the Great Hall of Bullfinch's Faneuil Hall, Boston, beneath a vast painting of Sen. Daniel Webster debating the preservation of the Union with Robert Hayne of South Carolina {in 1830}.’’

— Nigel Hamilton (born 1944), British-born historian

The Massachusetts senator’s speech is considered by many to be the greatest in U.S. Senate history.

New age of sail

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I mention this in part because New England has such a sailing tradition.

There’s a small but growing move to bring back sail for cargo ships, to reduce fuel costs and the ocean shipping’s sector’s carbon footprint. This could become a big deal over the next decade. A total of more than 100,000 ships transport more than 80 percent of products in world trade.

Tech advances are making mostly wind-powered vessels more economically attractive these days. They’re supplemented by engines to navigate in very narrow waters and when the wind fails. Note the mechanized systems for raising and adjusting sails, giant carbon-fiber masts, light aluminum hulls, highly computerized navigation systems and steadily improving wind forecasting. At the same time, giant rigid sails are being installed on what had been totally engine-powered vessels as power supplements.

Clarksons Research says a total of 165 cargo ships are either already using some wind power or will have wind systems installed. Maritime painters loved making pictures of clipper and other big sailing vessels. Now they have new dramatic images to play with.

When all seemed possible

“Piggy-Back” (acrylic paint, enamel paint, paper on canvas), by Bob Dilworth, in his show “When I Remembered Home,’’ at the Fitchburg (Mass.) Art Museum through Jan. 12

—Courtesy of the artist and Cade Tompkins Projects

Llewellyn King: A ‘missing link’ for renewable-energy generation

— Photo by Herbert Glarner

In a well-ordered laboratory in Owings Mills, a suburb of Baltimore, an engineer has been perfecting a device that might be called the missing link in renewable energy.

Now it is ready to begin its transformative role in electric generation. And to bring electricity to the remotest places in America, as well as adding it to the grid.

It is an invention that could cut the cost of new wind turbines, make solar more desirable and turn tens of thousands – yes, thousands — of U.S. streams and non-powered dams into power generators without huge civil engineering outlays.

The company is DDMotion, and its creative force is Key Han, president and chief scientist. Han has spent more than a decade perfecting his patented invention which takes variable inputs and converts them to a constant output.

In a stream, this consists of taking the variables in the water flow and turning them into a constant, reliable shaft output that can generate constant frequency ready to be fed to the grid. Likewise with wind and solar.

Han told me the environmental impact on a stream or river would be negligible, essentially undetected, but a reliable amount of grid-grade electricity could be obtained at all times in all kinds of weather.

He has dreams of a world where every bit of flowing water could be a resource for many power plants, and the same technologies would be essential in harnessing the energy of ocean currents.

A further advantage to Han’s constant-speed device is that with a rotating shaft, it is a source of what in the more arcane reaches of the electrical world is known as rotational inertia. Arcane but essential.

This is the slowing down of something that was once moving briskly, like stopping a car. In power generation, this can be a few seconds, but it is necessary to enable an electrical system to keep its output constant — 60 cycles per second in America, 50 cycles per second in Europe and parts of Asia. If that varies, the whole system fails. Blackout. Then the system must be recalibrated, and that can take days or several weeks for the whole grid.

Electricity needs rotational inertia. With fossil-fueled plants, this isn’t a problem: There is always rotational inertia in their rotating parts.

Wind power loses its inertia, which is there initially as the wind turns a shaft, but is lost as the power generated is groomed for the grid. It passes through a gearbox then to an inverter, which converts the power from direct current to grid-compatible alternating current.

Han says using his technology, the gearbox and the inverter can be eliminated and inertia provided. Also, most of the remaining hardware could be located on the ground rather than up in the air on the tower, making for less installation cost and easier maintenance.

Loss of inertia is becoming a problem for grids in Europe, where wind and solar are approaching half of the generating load. Germany, particularly, must create ancillary services.

Han told me, “DDmotion-developed speed converters can harness all renewable energy with benefits. For example, wind turbines can produce rotating inertia, therefore ancillary services are not required to keep the grid frequency stable, and river turbines without dams can generate baseload, therefore storage systems, such as batteries and pump storage are not required.”

DDMotion has been largely supported by Alfred Berkeley, chairman of Princeton Capital Management and a legend in the financial community. He served as president of Nasdaq and later as its vice chairman.

Han, who holds many patents relating to his work on infinitely variable motion controls, began his career at General Electric before founding DDMotion in 1990.

A native of South Korea, Han attended college in Montana so that he could fulfill his dream of becoming a professional cowboy. His resume includes roping and branding calves one summer.

If DDMotion succeeds as Han and his supporters hope, their missing link will vastly enhance the value of renewable energy and bring down its cost to the system and to consumers.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

Elements of us all

“Geomania’’ (still), (1987) (two-channel video matrix installation, color, sound, 15 minutes), by Vasulka Steina, at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Mass., through Jan. 12.

— Courtesy the artist and Berg Contemporary

Sam Pizzigati: UnitedHealth, Medicare Advantage and ‘social murder’

Grave with burial vault awaiting coffin.

Robert Lawton photo

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

More than 8,000 Americans die every day, many of them unnecessarily.

Why? Because the United States still doesn’t have a national health- care system that guarantees everyone adequate medical attention.

One particular American’s death has driven that point home. On Dec. 4, a gunman murdered Brian Thompson, UnitedHealthcare’s 50-year-old CEO. The bullet casings from the shooting read “deny,” “defend” and “depose.” Luigi Mangione, a 26-year-old highly educated man with a serious physical ailment, has been arrested in the case.

‘Deny,’’ “defend’’ and “depose” neatly sum up the gameplan America’s giant insurers so relentlessly follow: deny the claim, defend the lawsuit, depose the patient.

Last year, United pulled down $281 billion in revenue, boosting annual profits 33 percent over 2021. Thompson himself pocketed $10.2 million in personal compensation. And Andrew Witty, CEO of the overall UnitedHealth operation, collected $23.5 million, making him the nation’s highest-paid health-insurance CEO. (Brian Thompson and two other executives had been sued for insider trading.)

All private insurers profit by denying help to sick people who need it. But UnitedHealth’s operations have become especially rewarding thanks to the shadowy world of “Medicare Advantage,” the program that gives America’s senior citizens the option to contract out their Medicare to private health-service providers.

These private providers collect fixed fees from the federal government for each of the senior citizens they enroll. They profit when the cost of providing care to those seniors amounts to less than what the government pays them in fees. And that gives private providers an ongoing incentive to limit the care their patients receive.

No Medicare Advantage provider, the American Prospect’s Maureen Tkacik points out, has done more than UnitedHealthcare when it comes to “simply denying claims for treatments and procedures it unilaterally deems unnecessary.” Industry-wide, Medicare Advantage providers deny 16 percent of patient claims. UnitedHealthcare denied 32 percent last year.

The public’s frustration with health-insurance companies erupted bitterly after Thompson’s murder. UnitedHealth’s official Facebook report on Thompson’s death quickly drew 35,000 responses using the “Haha” emote.

“Thoughts and deductibles to the family,” read one reaction. “Unfortunately my condolences are out-of-network.”

“Compassion withheld,” read another, “until documentation can be produced that determines the bullet holes were not a preexisting condition.”

Some of the fiercest reactions to Thompson’s death came from within the medical community.

“This is someone who has participated in social murder on a mass scale,” a medical student wrote in one typical post.

“My patients died,” a nurse spat out in another, “while those b—-s enjoyed 26 million dollars.”

“If there’s anything our fractured country seems to agree on,” mused Bloomberg’s Lisa Jarvis, “it’s that the health care system is tragically broken, and the companies profiting from it are morally bankrupt.”

“To most Americans,” agreed The New Yorker’s Jia Tolentino, “a company like UnitedHealth represents less the provision of medical care than an active obstacle to receiving it.”

Among wealthier countries, Americans “die the youngest and experience the most avoidable deaths” despite spending almost twice as much on health care as others, a recent Commonwealth Fund Study found. And 25 percent of Americans, Gallup polling adds, have people in their family who have had to delay medical treatment for a serious illness because they couldn’t afford it.

Thompson’s murder won’t change those stats. The system that enriched him lives on — and the incoming Trump administration figures to make that system even worse. The corporate-friendly Heritage Foundation, in its controversial Project 2025 blueprint for the second Trump term, is proposing that Medicare Advantage become the “default option” for all new Medicare enrollees.

That would “essentially privatize Medicare” and significantly raise the program’s cost, warns analyst Heather Cox Richardson.

With Thompson’s death, America’s health-care powers feel and fear the American public’s anger now more than ever. The rest of us need to channel that anger toward ending this system that’s failed America’s health.

We need to remake health care into a vital public service — not a tool for profit.

Boston-based Sam Pizzigati, an Institute for Policy Studies associate fellow, co-edits Inequality.org, where a longer version of this op-ed originally appeared. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win. Follow him on Bluesky at @sgp.bsky.social.

Then call your cardiologist

Fish balls

“She boiled three good-sized potatoes for 25 minutes; then mashed them and stirred the fish into them. To this mixture she added five eggs, five generous teaspoons of butter and a little pepper {and} beat everything vigorously together. She cooked them in deep fat, picking up generous dabs of the mixture in a potbellied spoon. The resulting fish balls, eaten with her own brand of ketchup, made ambrosia seem like pretty dull stuff.’’

— Kenneth Roberts (1885-1957), American writer, especially known for his historical novels, in Trending into Maine (1938).

Avian and ancestor

“Goose and Ghost” (encaustic), by Nancy Whitcomb, in the 120th annual Little Pictures Show at the Providence Art Club through Dec. 22.

Alert the physics department

“Spark of Creation” (36 layers of glazes, oil on canvas), by Sloat Shaw, at the Cambridge (Mass.) Art Association.

Chris Powell: Public policies helped create Conn.’s underclass

New Haven

Emilie Foyer photo

MANCHESTER, Conn.

After three fatal shootings of young men in New Haven in less than two weeks, Mayor Justin Elicker gave news interviews to assure people that downtown is safe for holiday shopping, dining, and other festive activities. The mayor noted that, as with murders and shootings in other cities, most in New Haven involve people who know each other.

That is, no harm is likely to come to people visiting New Haven as long as they don't know anyone there. As for New Haven residents themselves, most figure that they'll probably be OK as long as they're not young men or associating with young men.

Essentially the mayor was saying that the mayhem is just a problem of the underclass. He noted that city social workers and police officers are pressing New Haven's young men to control their impulses to violence and change their dissolute lifestyle. Good luck with that.

Of course few if any elective offices are more difficult than mayor of an impoverished city, and Elicker was trying to protect New Haven's image. But outsiders should worry about the urban underclass. For the policies that created and sustain it and concentrate it in the cities are state and national policies, not city policies, and they are disgracefully designed to discourage people from worrying about the underclass, designed to let people think that it's the natural order for young men in the cities to be killing and maiming each other.

What are these policies?

They extend far beyond exclusive suburban zoning, which at least Connecticut's political left dares to challenge.

These policies begin with the destruction of poor families with welfare subsidies for childbearing outside marriage. Such subsidies proclaim that no one needs to be prepared to support one's own children and that fathers aren't needed anymore, though fatherlessness correlates heavily with bad outcomes for children, especially boys. Most children in Connecticut's cities live without fathers.

These policies continue with the repeal of standards in education and their replacement with social promotion, thereby destroying the incentive to learn for children who lack prepared and competent parents. Education is mostly a matter of parenting; without well-parented students who accept an obligation to learn, schools can't accomplish much. So government in Connecticut pretends that education is all about teacher salaries and busies itself with raises instead.

But having grown the underclass so large, government lacks the courage necessary even to recognize the disaster it has created.

What politicians will try to fix the problem of family destruction when it means telling so many of their constituents -- in the cities, most of their constituents -- that they should not have responded to the damaging incentives government gave them?

What politicians will try to restore education when it means telling educators, the most pernicious special interest, that it is a fraud for them to advance uneducated students from grade to grade and then to graduate them when the kids are unprepared to do more than menial work and to be citizens, and that this fraud leads them to demoralization and crime?

Destruction of educational standards worsened in last month's election. At the urging of its teacher unions, Massachusetts voted at referendum to repeal its requirement that high school students pass a proficiency test to graduate. The test was accused of racism for being too difficult for minority students, but it wasn't racist. The racism is the welfare system's depriving those students of fathers.

Connecticut doesn't dare attempt a high school graduation test or any proficiency test of high school seniors, lest the public discover that the huge amounts spent in the name of education produce so little and that most graduates never master high school work.

How can people raised in the welfare system and delivered to adulthood so uneducated be expected to support themselves? They can't. Hence the desire for state government to appropriate more and more to subsidize people who can't take care of themselves and their kids -- more food, day care, medical care, housing subsidies, and such.

So Connecticut's underclass keeps growing -- and shooting itself.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

As murky as the present

“Ever/After”(photomontage), by Marion Belanger and Martha Lewis, at Hartford (Conn.) Art School Galleries in the show “Pathways: HAS Faculty Show,’’ through Dec. 14.

The artwork ranges from porcelain to augmented reality, and represents a collective commitment to curiosity, process, and making.

Arthur Allen: Experts say RFK Jr. could be a public-health disaster

Unvaccinated child with measles, which can be fatal.

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

The availability of safe, effective Covid vaccines less than a year into the pandemic marked a high point in the 300-year history of vaccination, seemingly heralding an age of protection against infectious diseases.

Now, after backlash against public-health interventions culminated in President-elect Donald Trump’s nominating Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the country’s best-known anti-vaccine activist, as its top health official, infectious-disease and public-health experts and vaccine advocates say a confluence of factors could cause renewed, deadly epidemics of measles, whooping cough, and meningitis, or even polio.

“The litany of things that will start to topple is profound,” said James Hodge, a public-health-law expert at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. “We’re going to experience a seminal change in vaccine law and policy.”

“He’ll make America sick again,” said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of public-health law at Georgetown University.

State legislators who question vaccine safety are poised to introduce bills to weaken school-entry vaccine requirements or do away with them altogether, said Northe Saunders, who tracks vaccine-related legislation for the SAFE Communities Coalition, a group supporting pro-vaccine legislation and lawmakers.

Even states that keep existing requirements will be vulnerable to decisions made by a Republican-controlled Congress as well as by Kennedy and former House member Dave Weldon, should they be confirmed to lead the Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, respectively.

Both men — Kennedy as an activist, Weldon as a medical doctor and congressman from 1995 to 2009— have endorsed debunked theories blaming vaccines for autism and other chronic diseases. (Weldon has been featured in anti-vaccine films in the years since he left Congress.) Both have accused the CDC of covering up evidence this was so, despite dozens of reputable scientific studies to the contrary.

Kennedy’s staff did not respond to requests for comment. Karoline Leavitt, the Trump campaign’s national press secretary, did not respond to requests for comment or interviews with Kennedy or Weldon.

Kennedy recently told NPR that “we’re not going to take vaccines away from anybody.”

It’s unclear how far the administration would go to discourage vaccination, but if levels drop enough, vaccine-preventable illnesses and deaths might soar.

“It is a fantasy to think we can lower vaccination rates and herd immunity in the U.S. and not suffer recurrence of these diseases,” said Gregory Poland, co-director of the Atria Academy of Science & Medicine. “One in 3,000 kids who gets measles is going to die. There’s no treatment for it. They are going to die.”

During a November 2019 measles epidemic that killed 80 children in Samoa, Kennedy wrote to the country’s prime minister falsely claiming that the measles vaccine was probably causing the deaths. Scott Gottlieb, who was Trump’s first FDA commissioner, said on CNBC on Nov. 29 that Kennedy “will cost lives in this country” if he undercuts vaccination.

Kennedy’s nomination validates and enshrines public mistrust of government health programs, said Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The notion that he’d even be considered for that position makes people think he knows what he’s talking about,” Offit said. “He appeals to lessened trust, the idea that ‘There are things you don’t see, data they don’t present, that I’m going to find out so you can really make an informed decision.’”

Hodge has compiled a list of 20 actions the administration could take to weaken national vaccination programs, from spreading misinformation to delaying FDA vaccine approvals to dropping Department of Justice support for vaccine laws challenged by groups like Children’s Health Defense, which Kennedy founded and led before campaigning for president.

Kennedy could also cripple the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which Congress created in 1986 to take care of children believed harmed by vaccines — while partially protecting vaccine makers from lawsuits.

Before the law passed, the threat of lawsuits had shrunk the number of companies making vaccines in the United States — from 26 in 1967 to 17 in 1980 — and the remaining pertussis-vaccine producers were threatening to stop making it. The vaccine injury program “played an integral role in keeping manufacturers in the business,” Poland said.

Kennedy could abolish the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, whose recommendation for using a vaccine determines whether the government pays for it through the 30-year-old Vaccines for Children program, which makes free immunizations available to more than half the children in the United States. Alternatively, Kennedy could stack the committee with allies who oppose new vaccines, and could, in theory at least, withdraw recommendations for vaccines like the 53-year-old measles-mumps-rubella shot, a favorite target of the anti-vaccine movement.

Meanwhile, infectious-disease threats are on the rise or on the horizon. Instead of preparing, as a typical incoming administration might, Kennedy has threatened to shake up the federal health agencies. Once in office, he’ll “give infectious disease a break” to focus on chronic ailments, he said at a Children’s Health Defense conference last month in Georgia.

The H5N1 virus, or bird flu, that has spread through cattle herds and infected at least 55 people could erupt in a new pandemic, and other threats like mosquito-borne dengue fever are rising in the U.S.

Traditional childhood diseases are also making their presence felt, in part because of neglected vaccination. The U.S. has seen 16 measles outbreaks this year — 89% of cases are in unvaccinated people — and a whooping cough epidemic is the worst since 2012.

“So that’s how we’re starting out,” said Peter Hotez, a pediatrician and virologist at the Baylor College of Medicine. “Then you throw into the mix one of the most outspoken and visible anti-vaccine activists at the head of HHS, and that gives me a lot of concern.”

The share prices of drug companies with big vaccine portfolios have plunged since Kennedy’s nomination. Even before Trump’s victory, vaccine exhaustion and skepticism had driven down demand for newer vaccines like GSK’s RSV and shingles shots.

Kennedy has ample options to slow or stop new vaccine releases or to slow sales of existing vaccines — for example, by requiring additional post-market studies or by highlighting questionable studies that suggest safety risks.

Kennedy, who has embraced conspiracy theories such as that HIV does not cause AIDS and that pesticides cause gender dysphoria, told NPR there are “huge deficits” in vaccine safety research. “We’re going to make sure those scientific studies are done and that people can make informed choices,” he said.

Kennedy’s nomination “bodes ill for the development of new vaccines and the use of currently available vaccines,” said Stanley Plotkin, a vaccine-industry consultant and inventor of the rubella vaccine in the 1960s. “Vaccine development requires millions of dollars. Unless there is prospect of profit, commercial companies are not going to do it.”

Vaccine advocates, with less money on hand than the better-funded anti-vaccine advocates, see an uphill battle to defend vaccination in courts, legislatures, and the public square. People are rarely inclined to celebrate the absence of a conquered illness, making vaccines a hard sell even when they are working well.

While many wealthy people, including potion and supplement peddlers, have funded the anti-vaccine movement, “there hasn’t been an appetite from science-friendly people to give that kind of money to our side,” said Karen Ernst, director of Voices for Vaccines.

‘He’s Serious as Hell’

“RFK Jr. was a punch line for a lot of people, but he’s serious as hell,” Ernst said. “He has a lot of power, money, and a vast network of anti-vaccine parents who’ll show up at a moment’s notice.” That’s not been the case with groups like hers, Ernst said.

On Oct. 22, when an Idaho health board voted to stop providing covid vaccines in six counties, there were no vaccine advocates at the meeting. “We didn’t even know it was on the agenda,” Ernst said. “Mobilization on our side is always lagging. But I’m not giving up.”

The kaleidoscopic change has been jarring for Walter Orenstein, who persuaded states to tighten school mandates to fight measles outbreaks as head of the CDC’s immunization division from 1988 to 2004.

“People don’t understand the concept of community protection, and if they do they don’t seem to care,” said Orenstein, who saw some of the last cases of smallpox as a CDC epidemiologist in India in the 1970s, and frequently cared for children with meningitis caused by H. influenzae type B bacteria, a disease that has mostly disappeared because of a vaccine introduced in 1987.

“I was so naïve,” he said. “I thought that Covid would solidify acceptance of vaccines, but it was the opposite.”

Lawmakers opposed to vaccines could introduce legislation to remove school-entry requirements in nearly every state, Saunders said. One bill to do this has been introduced in Texas, where what’s known as the vaccine choice movement has been growing since 2015 and took off during the pandemic, fusing with parents’ rights and anti-government groups opposed to measures like mandatory shots and masking.

“The genie is out of the bottle, and you can’t put it back in,” said Rekha Lakshmanan, chief strategy officer at the Immunization Partnership in Texas. “It’s become this multiheaded thing that we’re having to reckon with.”

In the last full school year, more than 100,000 Texas public school students were exempted from one or more vaccinations, she said, and many of the 600,000 homeschooled Texas kids are also thought to be unvaccinated.

In Louisiana, the state surgeon general distributed a form letter to hospitals exempting medical professionals from flu vaccination, claiming the vaccine is unlikely to work and has “real and well established” risks. Research on flu vaccination refutes both claims.

The biggest threat to existing vaccination policies could be plans by the Trump administration to remove civil service protections for federal workers. That jeopardizes workers at federal health agencies whose day-to-day jobs are to prepare for and fight diseases and epidemics. “If you overturn the administrative state, the impact on public health will be long-term and serious,” said Dorit Reiss, a professor at the University of California’s Hastings College of Law.

Billionaire Elon Musk, who has the ear of the incoming president, imagines cost-cutting plans that are also seen as a threat.

“If you damage the core functions of the FDA, it’s like killing the goose that laid the golden egg, both for our health and for the economy,” said Jesse Goodman, the director of the Center on Medical Product Access, Safety and Stewardship at Georgetown University and a former chief science officer at the FDA. “It would be the exact opposite of what Kennedy is saying he wants, which is safe medical products. If we don’t have independent skilled scientists and clinicians at the agency, there’s an increased risk Americans will have unsafe foods and medicine.”

Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable illness could be alarming, but would they be enough to boost vaccination again? Ernst of Voices for Vaccines isn’t sure.

“We’re already having outbreaks. It would take years before enough children died before people said, ‘I guess measles is a bad thing,’” she said. “One kid won’t be enough. The story they’ll tell is, ‘There was something wrong with that kid. It can’t happen to my kid.’”

Arthur Allen is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter.

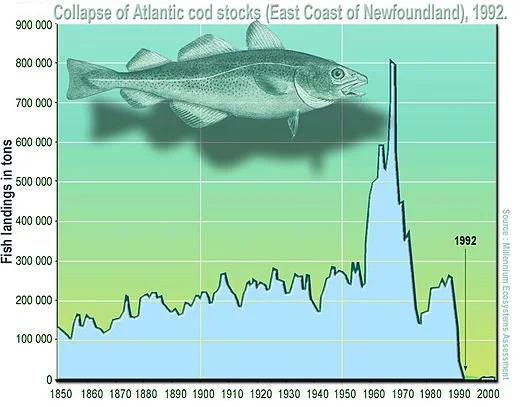

Jumping the gun on cod fishing?

Northwest Atlantic cod stocks were severely overfished in the 1970s and 1980s, leading to their abrupt collapse in 1992.

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Against the advice of scientists, Canada this year lifted a moratorium on cod fishing that was imposed back in 1994 after cod stocks plummeted off the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. There’s been a bit of revival in the past few years, but the stocks remain far below what they were for hundreds of years following European colonization. (The proximity of vast stocks of cod, which, importantly, could be easily salted and preserved, was part of what made New England and, to a lesser extent, the Maritime provinces, prosperous starting in the 18th Century. Indeed, what became known as Boston Brahmins also used to be called “The Codfish Aristocracy.’’)

The moratorium was lifted at least in part for political reasons. Newfoundland/Labrador suffered mightily and angrily from the fishing ban, which forced many “Newfies’’ to leave. Politics, public opinion and science often don’t happily co-exist. Look at America’s COVID experience.

In any case, Canada might now be jumping the gun, leading to another crash in cod stocks.

Meanwhile, warming water and changes in currents associated with climate change mean that the mix of fish species off New England and the Maritimes will continue to change in predictable and unpredictable ways over the next few years.

(I’m a halibut fan myself; that fish generally comes from the more northern waters off the Maritime provinces. I had some the other week at a business dinner in a New York restaurant that was so dark that I asked for a flashlight to read the menu and the alarming bill; I can’t afford Gotham anymore.)

Totalitarian Temptations

He probably won’t win the final election, set for Dec. 8, but far-right Romanian politician Calin Georgescu, who is anti-NATO, anti-Ukraine and pro-Russian, was the top voter in the country’s first election stage, on Nov. 24, when he won about 23 percent of the vote. But he’s still troubling for all those who treasure democracy.

He's an admirer of the country’s virulently anti-semitic fascist dictator and Hitler ally Ion Antonescu (1882-1946), who was executed for war crimes. He reflects the authoritarian/totalitarian temptation – a belief that a “strong leader’’ can end a nation’s frustrations. And for those uncooperative citizens not lusting for dictatorship to fix all their national woes? The sort of extreme Orwellian surveillance strategies being perfected by Xi Jinping’s tyranny in China can keep them well under control.

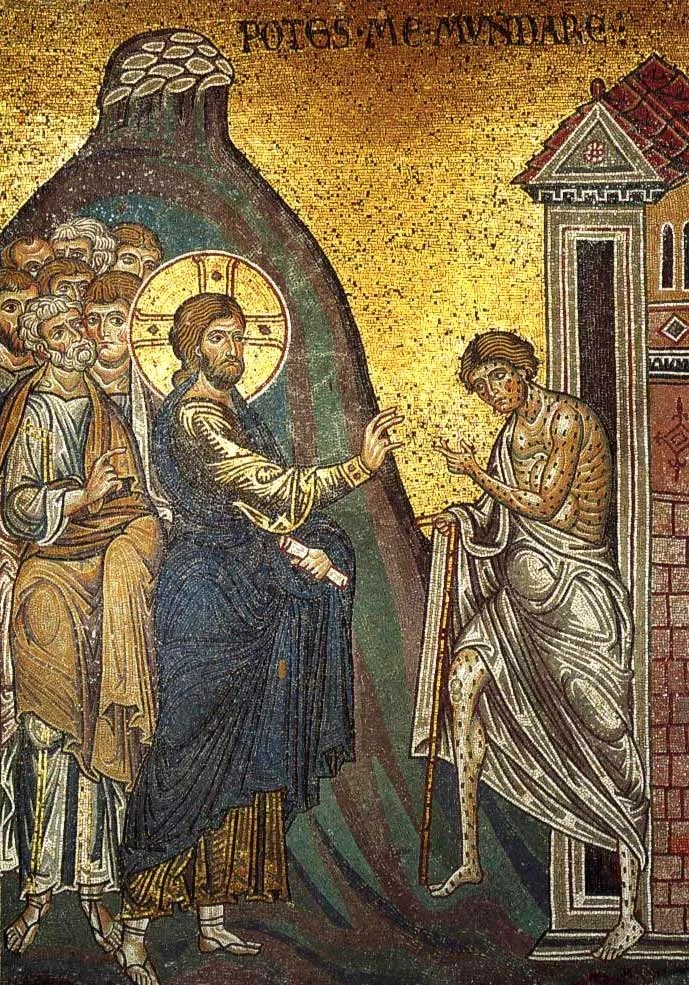

Joanne M. Pierce: An AI Jesus can’t absolve you of your sins

Jesus cleansing a leper, a medieval mosaic from the Monreale (Italy) Cathedral, late 12th to mid-13th centuries.

Text from The Conversation

WORCESTER, Mass.

This autumn, a Swiss Catholic church installed an AI Jesus in a confessional to interact with visitors.

The installation was a two-month project in religion, technology and art titled “Deus in Machina,” created at the University of Lucerne. The Latin title literally means “god from the machine”; it refers to a plot device used in Greek and Roman plays, introducing a god to resolve an impossible problem or conflict facing the characters.

This hologram of Jesus Christ on a screen was animated by an artificial intelligence program. The AI’s programming included theological texts, and visitors were invited to pose questions to the AI Jesus, viewed on a monitor behind a latticework screen. Users were advised not to disclose any personal information and confirm that they knew they were engaging with the avatar at their own risk.

AI Jesus confessional.

Some headlines stated that the AI Jesus was actually engaged in the ritual act of hearing people’s confessions of their sins, but this wasn’t the case. However, even though AI Jesus was not actually hearing confessions, as a specialist in the history of Christian worship, I was disturbed by the act of placing the AI project in a real confessional that parishioners would ordinarily use.

A confessional is a booth where Catholic priests hear parishioners’ confessions of their sins and grant them absolution, forgiveness, in the name of God. Confession and repentance always take place within the human community that is the church. Human believers confess their sins to human priests or bishops.

Early history

The New Testament scriptures clearly stress a human, communal context for admitting and repenting for sins.

In the Gospel of John, for example, Jesus speaks to his apostles, saying, “Whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven, and whose sins you shall retain they are retained.” And in the epistle of James, Christians are urged to confess their sins to one another.

Churches in the earliest centuries encouraged public confession of more serious sins, such as fornication or idolatry. Church leaders, called bishops, absolved sinners and welcomed them back into the community.

From the third century on, the process of forgiving sins became more ritualized. Most confessions of sins remained private – one on one with a priest or bishop. Sinners would express their sorrow in doing penance individually by prayer and fasting.

However, some Christians guilty of certain major offenses, such as murder, idolatry, apostasy or sexual misconduct, would be treated very differently.

These sinners would do public penance as a group. Some were required to stand on the steps of the church and ask for prayers. Others might be admitted in for worship but were required to stand in the back or be dismissed before the scriptures were read. Penitents were expected to fast and pray, sometimes for years, before being ritually reconciled to the church community by the bishop.

Medieval developments

During the first centuries of the Middle Ages, public penance fell into disuse, and emphasis was increasingly placed on verbally confessing sins to an individual priest. After privately completing the penitential prayers or acts assigned by the confessor, the penitent would return for absolution.

The concept of Purgatory also became a widespread part of Western Christian spirituality. It was understood to be a stage of the afterlife where the souls of the deceased who died before confession with minor sins, or had not completed penance, would be cleansed by spiritual suffering before being admitted to heaven.

Living friends or family of the deceased were encouraged to offer prayers and undertake private penitential acts, such as giving alms – gifts of money or clothes – to the poor, to reduce the time these souls would have to spend in this interim state.

Other developments took place in the later Middle Ages. Based on the work of the theologian Peter Lombard, penance was declared a sacrament, one of the major rites of the Catholic Church. In 1215, a new church document mandated that every Catholic go to confession and receive Holy Communion at least once a year.

Priests who revealed the identity of any penitent faced severe penalties. Guidebooks for priests, generally called Handbooks for Confessors, listed various types of sins and suggested appropriate penances for each.

The first confessionals

Until the 16th century, those wishing to confess their sins had to arrange meeting places with their clergy, sometimes just inside the local church when it was empty.

But the Catholic Council of Trent changed this. The 14th session in 1551 addressed penance and confession, stressing the importance of privately confessing to priests ordained to forgive in Christ’s name.

Soon after, Charles Borromeo, the cardinal archbishop of Milan, installed the first confessionals along the walls of his cathedral. These booths were designed with a physical barrier between priest and penitent to preserve anonymity and prevent other abuses, such as inappropriate sexual conduct.

Similar confessionals appeared in Catholic churches over the following centuries: The main element was a screen or veil between the priest confessor and the layperson, kneeling at his side. Later, curtains or doors were added to increase privacy and ensure confidentiality.

A 17th-century confessional at the Toulouse St. Stephen’s Cathedral. Didier Descouens via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Rites of penance in contemporary times

In 1962, Pope John XXIII opened the Second Vatican Council. Its first document, issued in December 1963, set new norms for promoting and reforming Catholic liturgy.

Since 1975, Catholics have three forms of the rite of penance and reconciliation. The first form structures private confession, while the second and third forms apply to groups of people in special liturgical rites. The second form, often used at set times during the year, offers those attending the opportunity to go to confession privately with one of the many priests present.

The third form can be used in special circumstances, when death threatens with no time for individual confession, like a natural disaster or pandemic. Those assembled are given general absolution, and survivors confess privately afterward.

In addition, these reforms prompted the development of a second location for confession: Instead of being restricted to the confessional booth, Catholics now had the option of confessing their sins face-to-face with the priest.

To facilitate this, some Catholic communities added a reconciliation room to their churches. Upon entering the room, the penitent could choose anonymity by using the kneeler in front of a traditional screen or walk around the screen to a chair set facing the priest.

Over the following decades, the Catholic experience of penance changed. Catholics went to confession less often, or stopped altogether. Many confessionals remained empty or were used for storage. Many parishes began to schedule confessions by appointment only. Some priests might insist on face-to-face confession, and some penitents might prefer the anonymous form only. The anonymous form takes priority, since the confidentiality of the sacrament must be maintained.

In 2002, Pope John Paul II addressed some of these problems, insisting that parishes make every effort to schedule set hours for confessions. Pope Francis himself has become concerned with reviving the sacrament of penance. In fact, he demonstrated its importance by presenting himself for confession, face-to-face, at a confessional in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Perhaps, in the future, a program like AI Jesus could offer Catholics and interested questioners from other faiths information, advice, referrals and limited spiritual counseling around the clock. But from the Catholic perspective, an AI, with no experience of having a human body, emotions and hope for transcendence, cannot authentically absolve human sins.

Joanne M. Pierce is a professor emerita of religious studies at The College of the Holy Cross, in Worcester.

She does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations.

‘Fragility and strength’

“Striped Beach with Boy”(lumiere paints on cotton, quilted), by West Hartford, Conn.-based artist and retired lawyer Diane Cadrain, in her show “The Ripple Effect: Images of Cape Cod,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Dec. 29.

“I attempt to create images that combine fragility with strength and the evanescent with the eternal. The sand ripples on the beaches of Cape Cod are perfect subjects for me because they are always changing, but always the same, and despite the visual strength of their patterns, they can be washed away with the next tide.”

Llewellyn King: Old newspaper days, and television, too

Linotype machine keyboard.

— Photo by Emdx

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

On Dec. 13, I will receive an award and give a dinner talk at the National Press Club in Washington, recognizing my 68 years as a journalist and my 58 years as a member of the club.

This recognition is from a club subsection, known as the Owls. Silver Owls are those who have roosted at the club for 25 years or longer; Golden Owls, 50 years or more; and Platinum Owls, 60 years or longer.

You may think that the hot-type days in newspapers are long past, along with black-and-white television. They may be, but the denizens of that time live on — or some of us do.

We will crowd the storied National Press Club ballroom to raise a glass to the time when headlines had to fit to an exact letter count, when wire services moved the news over teleprinters at 64 words a minute: It could be the biggest story in the world, but it would be moved slower than the speed of reading.

The trick was to break the news into very short takes and move it on several printers. The principal teleprinter of the news services, UPI, AP and Reuters, was equipped with a “bulletin” bell which rang when the biggest news, like an assassination, broke.

In the composing room, where “metal” (you dared not call it lead, even though it was predominantly lead with some tin and antimony) was cast into type and into “furniture,” the rules and the spacing bars that went between the lines of type, craftsmanship ruled.

At one side of that great hive were the Linotype machines, operated by skilled people who could change fonts and type sizes by levering up or down the brass boxes that contained the dies of the type. They were the kings and queens of that art, secure and unflappable. Each Linotype machine contained a thousand parts, according to the Museum of Printing in Haverhill, Mass.

In a rush the printers (note to laymen: printers set and handled the type), the people who ran the presses were pressmen, could assemble a whole page in minutes. If news had broken or, heaven forfend, a page had been “pied” (dropped, type all over the floor) then everything had to be reset and assembled.

Television — when I first worked in it in London, in the days of black-and-white — had its own foibles and culture, and the love of a glass of something.

The equivalent of the printers were the film editors, craftsmen and women all. One of the most skilled, who had had a long career in movies, would entertain us at the in-house bar in the BBC news studios in North London, by swinging a full pint mug of beer over his head without spilling any.

With the same dedication, he would slice and link the celluloid on deadline. He was the man who would save the day, especially if film came in late. Tape was in its infancy.

In the newsrooms on newspapers, tactically just one floor above the composing room, there were the journalists — that irregular army of misfits and egotists who made up a subculture unique to themselves. In Britain, they were referred to somewhere as “the shabby people who smell of drink.” That was true of journalists all over the world in those days. I can attest, bear witness. I was there.

Among the journalists, writers, editors, cartoonists, columnists, photographers, designers, secretaries and librarians were a cast of characters that was almost always the same in every newsroom, print or television. There was the Beau Brummell, the lover, the agony aunt, the gossip, the budding author, and the drunk (who wrote better than anyone else and was tolerated because of that). Then sadly, the gambler.

It seemed to me the drinkers had camaraderie and laughter, the gamblers just losses.

That began to change about 1970, when I was at The Washington Post. There were still drinkers who did the deed at the New York Lounge, a hole in the wall next to the more famous but less used by us Post Pub. But the drinking was definitely down. Among the younger members of the staff, pot was the recreational drug. The older ones still favored a drink.

In London, the big newspapers and the BBC maintained bars in their offices. It made it easy to find people when they were needed.

At the venerable New York Herald Tribune after the first edition closed at 7:30 p.m., the entire editorial staff, it seemed, went downstairs and around the block to the Artist (cq) and Writers, also called Bleaks. It wasn’t known for the quality of its carbonated water, unless that was mixed with something brown.

At the Baltimore News-American, there was a secret route through the mechanical departments, enabling thirsty scribblers to reach the nearest bar undetected.

At the Washington Daily News, which belonged to the Scripps Howard chain of newspapers, the editor was known to favor the nearest bar, an Irish establishment called Matt Kane’s.

At the National Press Club celebration, we will raise one to the days of wine and roses, great stories and wordsmithing, and the fabulous adventure of it — the bad food, terrible hours, poor pay, long stakeouts, days far from home, and always, as my late first wife and great journalist, Doreen King, said, “the inner core of panic” about getting things right. We do care, more than our readers and viewers know.

There is, for all of its tribulations, no greater, more exciting place to be than in a newsroom as big news is breaking.

You are there, inside history.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He is based in Rhode Island.

White House Chronicle