Kennedy could menace Boston medical complex

View over the Longwood Medical Area.

Text edited from an article in The Boston Guardian

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian’s board.)

If Robert F. Kennedy Jr. becomes secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services he could pose serious funding and economic problems for the Longwood Medical Area (LMA).

Institutions in Longwood rely heavily on funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). But Kennedy has said he’ll redirect half of the agency’s budget to holistic health, and Trump is expected to propose steep cuts to its research budget.

The LMA makes Boston a hub of health-care innovation and comprises a sizeable part of the city’s economy.

If the NIH budget is cut, Longwood’s research capabilities would decrease. But the city could also suffer significant economic consequences.

“The LMA is one of the densest clusters of research activity in the nation, with more NIH awards for its research endeavors than other similar academic biomedical clusters in the U.S.,” said David Sweeney, the president and CEO of the Longwood Collective, a non-profit organization which maintains the area.

The LMA also receives the most NIH research funding per capita in the United States. Institutions in the LMA have collectively received $1.2 billion in NIH-funded research grants in 2024, according to the Longwood Collective. In 2023, they received $1.4 billion.

“Most NIH-funded Boston hospitals are located in the Longwood Medical Area, making it an epicenter of medical training, research, and health care,” the Boston Planning Department stated in its most recent annual report on NIH funding throughout the city. The LMA contains 21 hospitals.

NIH funding is important because it is cost-effective compared to other types of funding. “It has the highest cost reimbursable rate across all sponsor types,” a spokesperson for the Mass General Brigham hospitals said. “Most awards are for four or five fiscal years, which provides financial stability to people working on these grants.”

If NIH funding were cut, the spokesperson said, it would take about five years to notice a decline. As existing NIH grants ran out, researchers would need to apply for other funds, which might not be as lucrative or stable, and they might struggle to upkeep their current volume in research output.

That also suggests possible economic decline.

“This research funding plays a major role in supporting the innovation ecosystem in the state and its associated reputational, workforce, and business creation benefits,” the Longwood Collective stated in a 2020 economic impact report, citing spending by LMA employees, students, and institutions. “All of these activities form the economic ‘ripple effect’ of the activity occurring within the LMA.”

The news about Kennedy has already had economic effects in the state. The Boston Business Journal reported the other week that stock prices for such major Massachusetts life-science companies as Moderna, Biogen and Vertex Pharmaceuticals plummeted after his nomination.

Kennedy has said he plans to immediately replace 600 NIH employees, restructure the agency from 27 departments to 15, and commit half of its research funding towards “preventive, alternative and holistic approaches to health.” He has previously criticized the NIH for not funding research on whether and how vaccines impact autism.

Heading for a concussion

“Morning Run” (oil on canvas), by Peterboro, N.H., artist Gary Shepard at Vermont Artisan Designs, Brattleboro, Vt., Dec. 6-Jan. 2.

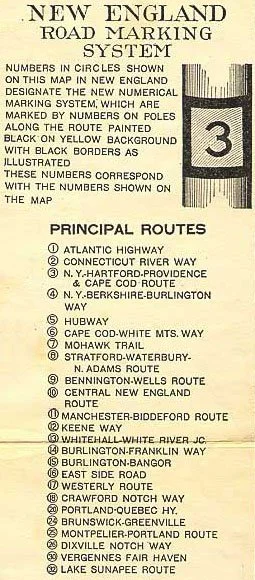

Compare them

W.E.B. Du Bois in 1907.

“The cost of liberty is less than the price of repression.’’

— W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963), in John Brown.

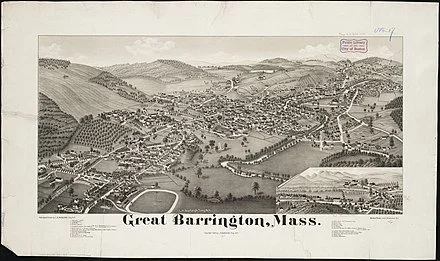

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil-rights activist. Born and raised in Great Barrington, Mass., in The Berkshires, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community, compared to most of America, and especially compared to the ruthless racism of the Jim Crow South.

Great Barrington in 1884.

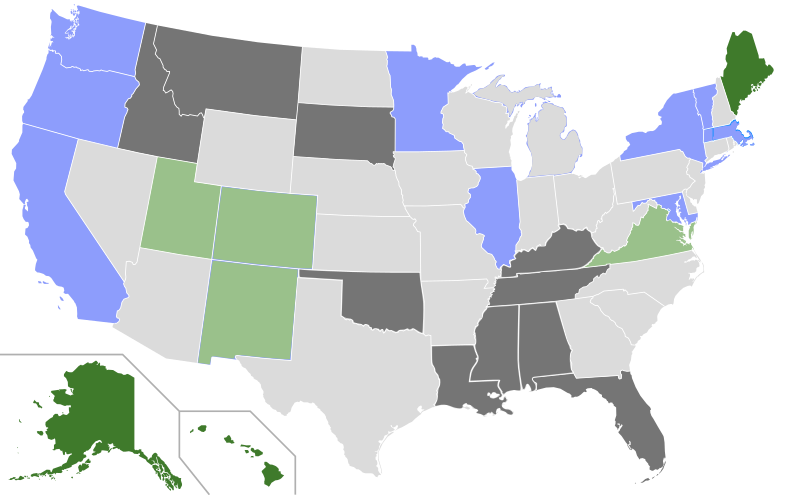

Chris Powell: Not ready for ranked voting?

Ranked-choice voting in U.S.

Dark green: Some statewide elections.

Light green: Local option for municipalities to opt in.

Blue: Option for localities in some jurisdictions.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Gov. Ned Lamont and some good-government activists want Connecticut to adopt ranked-choice voting. This is the mechanism of "instant runoff" elections in which voters rank candidates in order of their preference. Candidates receiving the fewest votes are eliminated and their votes are transferred to the remaining candidates in accordance with voter preferences until one candidate achieves a majority, not a mere plurality.

Under ranked-choice voting people still get only one vote but are allowed to change it prospectively.

The governor has appointed a group to study the issue.

Ranked-choice voting might get complicated with an office for which there were many candidates, but it would be pretty simple where there were only three or four.

Building a majority for the winner is the great virtue of ranked-choice voting. It works against candidates who represent extremes but who might win if a moderate majority is divided among two or more candidates.

In recent decades Connecticut has had some notable elections that had three or more candidates and whose winners well may not have won a runoff.

There was the 1994 election for governor, a four-way race won by John G. Rowland, a Republican, with only 36% of the vote, the total vote being split by minor-party liberal and minor-party conservative candidates.

The state's election for U.S. senator in 1970 was won by Lowell P. Weicker Jr., a Republican, with only 42% of the vote, as the Democratic vote was split by Sen. Thomas J. Dodd's independent candidacy after his party rejected him for embezzling campaign funds.

Those elections are reasons for Connecticut Democrats and liberals particularly to aspire to ranked-choice voting. But Connecticut Republicans and conservatives have a reason to aspire to it as well, though they haven't realized it yet.

That reason is Connecticut's Working Families Party, which exists to push the Democratic Party to the left. The Working Families Party ordinarily cross-endorses Democrats who lean left but will threaten to run its own candidates against Democrats who aren't leftist enough, thus splitting the Democratic vote and aiding Republicans. Ranked-choice voting would eliminate the Working Families Party's leverage over Democrats, since people voting for a Working Families candidate almost certainly would list the Democratic candidate as their second choice over any Republican. Then moderate Democrats wouldn't have to worry about the far-left party anymore.

Meanwhile Connecticut has no far-right minor party to threaten Republican candidates in the same way. (Neighboring New York has both liberal and conservative minor parties that exist to push the major parties left and right, respectively.)

Indeed, with ranked-choice voting no major-party candidates would not have to worry about any "spoiler" candidates anymore.

Unfortunately, a week after the recent election a report from Connecticut's Hearst newspapers indicated that the state isn't ready for ranked-choice voting and may not even be fully competent to hold ordinary elections.

Hearst's investigation found that at least six municipalities reported to the secretary of the state voting data with gross mistakes -- like more votes cast than registered voters and even more precincts reporting than real precincts. As might have been expected, Hartford failed in both respects, reporting more precincts than it had and more voters participating than votes cast.

Hearst's investigation noticed these errors before election officials did.

There was no suggestion of corruption here, just negligence, but it may be chronic. For the Hearst report added, "Last year Secretary of the State Stephanie Thomas traveled to East Haven more than 2½ months after Connecticut's municipal elections to bestow an award for high voter turnout, only to learn that the apparent large number of voters was due to a data-entry error."

Running an election can be exhausting, and registrars and their aides are often heroic. Connecticut's recent conversion to early voting may make things harder. But before Connecticut tries revolutionizing more of its voting procedures, it should perfect the current ones. That's the study group the governor should appoint.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

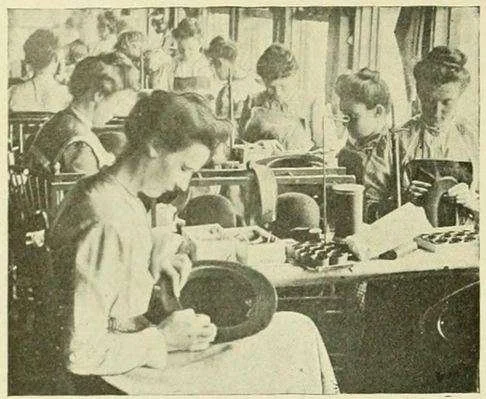

Danbury’s deadly hat industry

From the New England Historical Society

The 19th-Century hat factories of Danbury, Conn., made physical wrecks of thousands of workers. They turned them into mad hatters with symptoms known as the Danbury shakes.

In a Danbury hat mill.

]

Hat makers used mercuric nitrate to make hats. Many developed mercury poisoning, manifested as drooling, pathological shyness, irritability and tremor. Mercury poisoning looked a lot like drunkenness, a handy misconception for employers to exploit.

Here’s the whole article.

William Morgan: Journey to the exotic White Mountains

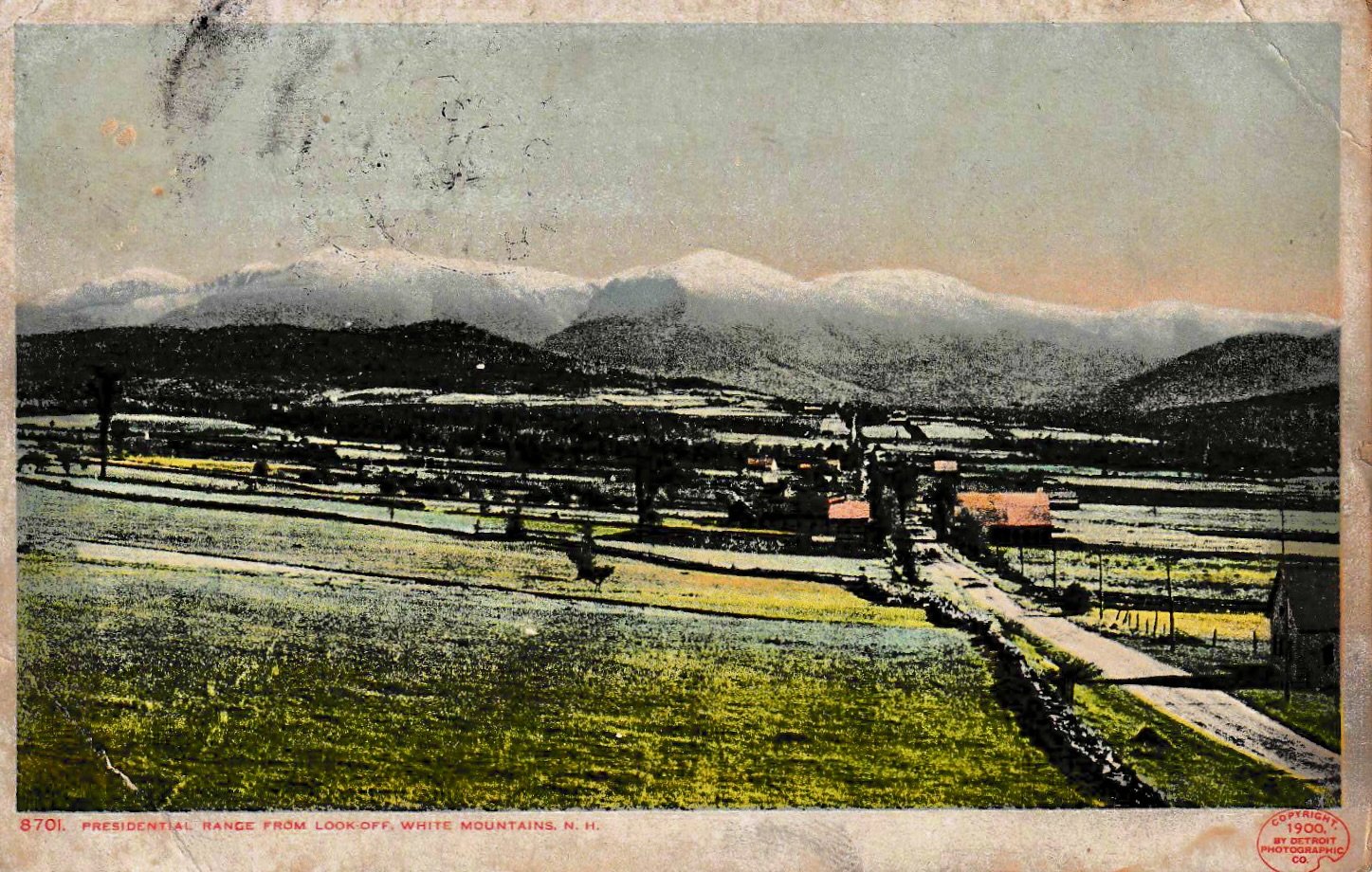

In the autumn of 1907 Bertha made a trip to the White Mountains. While there she posted a picture postcard to her friend Emma Merrill in Raymond, N.H., a town halfway between Concord and Portsmouth. The ubiquitous Detroit Photographic Company labeled its panorama “Presidential Range from Look-Off, White Mountains, N.H.” The colored photo shows a surprisingly flat landscape in the foreground, with a few houses and barns. Some might mistake the view for that of the Dolomites rising above Italy’s Po Valley.

We forget how provincial New Hampshire was a century and a quarter ago and how exotic the White Mountains must have seemed.

I had a girlfriend from Concord once, and her parents took their honeymoon in northern New Hampshire. More recently, while I was renewing my driver’s license in Keene, a farmer in line in front of me, allowed as to how he had never been to Concord.

Did Bertha take any more trips in her lifetime? We have tantalizing little information to form any sort of a picture of her. Yet Find a Grave connects us with Emma J. Merrill, who is buried in New Pine Grove Cemetery, in Raymond. She died in 1954 at 79. Her husband, William, died the same year; their gravestone tells us that he was two years younger than Emma. Bertha’s postcard, which I bought for a dollar in New Bedford, saves the two women from obscurity.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian, critic and photographer. He is author of numerous books with New England themes, including The Cape Cod Cottage, which is being published by Abbeville Press this winter.

A color trip

“Color Cascade’’ in the show “Experience Night Lights,’’ at the New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill, in Boylston, Mass., through Jan. 5.

The organization says:

“Wander through formal gardens and conservatories illuminated by more than a quarter of a million artfully arranged lights. With displays showcasing a creative new theme each year, this dazzling, one-of-a-kind spectacle is unmatched in the region. Festive activities such as outdoor skating, s’mores roasting, and holiday shopping promise an unforgettable experience for visitors of all ages.’’

Boylston Commons

— Photo by Allen Karsina

Offshore wind turbines vs. damage from trawling and fossil-fuel addiction

Components of offshore wind turbines being staged for Vineyard Wind 1 at New Bedford.

Wosketomp photo

From ecoRI.org column by Frank Carini

Ever since the Block Island Wind Farm first became an idea more than a decade ago, the commercial fishing industry has that warned offshore turbines will industrialize the ocean and hurt ecosystems….

Offshore wind turbines, especially during construction, certainly add to the cacophony of underwater noise created by yachts (mega or otherwise), container ships, barges, oil and gas drilling, sonar, and military exercises that stress marine mammals and other sea life.

Centuries of commercial fishing and whaling also industrialized the oceans. They have had a profound impact on the marine environment. Combined with the extraction, transportation, and the burning of fossil fuels at sea, these two industries have caused significant marine distress.

Wherever you go there you are

View of the Presidential Range from the Bretton Woods, N.H. resort. It was also the site of the 1944 international conference called to make plans for the Free World’s post-World War II economic system.

“My outer world and inner make a pair.

But would the two be always of a kind?

Another latitude, another mind?

Or would I be New England anywhere?’’

— From “New England Mind,’’ by Robert Francis (1901-1987), American poet and teacher who lived most of life in Amherst, Mass. Here’s the whole poem.

Dream on, America

William James in 1903.

“The deadliest enemies of nations are not their foreign foes; they always dwell within their borders. … The nation blessed above all nations is she in whom the civic genius of the people does the saving day by day, by acts without external picturesqueness; by speaking, writing, voting reasonably; by smiting corruption swiftly; by good temper between parties; by the people knowing true men when they see them, and preferring them as leaders to rabid partisans or empty quacks.”

William James (1842-1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist who was based at Harvard. Many consider him “The Father of American Psychology”. He was the brother of Henry James, the novelist.

Gifts from the sea

“Neptune's Platter” (ceramic, metal, glaze, patina), by Sally S. Fine, at Boston Sculptors Gallery through Dec. 8

— Photo by Will Howcroft

Michael Carrafiello: The Mass. Bay Puritans and the quite different ‘Pilgims’ subsect

“The Early Puritans of New England Going to Church,’’ 1867 oil painting by George Henry Boughton.

‘OXFORD, Ohio

Every November, numerous articles recount the arrival of 17th-century English Pilgrims and Puritans and their quest for religious freedom. Stories are told about the founding of Massachusetts Bay Colony and the celebration of the first Thanksgiving feast.

In the popular mind, the two groups are synonymous. In the story of the quintessential American holiday, they have become inseparable protagonists in the story of the origins.

But as a scholar of both English and American history, I know there are significant differences between the two groups. Nowhere is this more telling than in their respective religious beliefs and treatment of Native Americans.

Where did the Pilgrims come from?

Pilgrims arose from the English Puritan movement that originated in the 1570s. Puritans wanted the English Protestant Reformation to go further. They wished to rid the Church of England of “popish” – that is, Catholic – elements like bishops and kneeling at services.

Each Puritan congregation made its own covenant with God and answered only to the Almighty. Puritans looked for evidence of a “godly life,” meaning evidence of their own prosperous and virtuous lives that would assure them of eternal salvation. They saw worldly success as a sign, though not necessarily a guarantee, of eventual entrance into heaven.

After 1605, some Puritans became what scholar Nathaniel Philbrick calls “Puritans with a vengeance.” They embraced “extreme separatism,” removing themselves from England and its corrupt church.

These Puritans would soon become “Pilgrims” – literally meaning that they would be prepared to travel to distant lands to worship as they pleased.

In 1608, a group of 100 Pilgrims sailed to Leiden, Holland and became a separate church living and worshipping by themselves.

They were not satisfied in Leiden. Believing Holland also to be sinful and ungodly, they decided in 1620 to venture to the New World in a leaky vessel called the Mayflower. Fewer than 40 Pilgrims joined 65 nonbelievers, whom the Pilgrims dubbed “strangers,” in making the arduous journey to what would be called Plymouth Colony.

Hardship, survival and Thanksgiving in America

Most Americans know that more than half of the Mayflower’s passengers died the first harsh winter of 1620-21. The fragile colony survived only with the assistance of Native Americans – most famously Squanto. To commemorate, not celebrate, their survival, Pilgrims joined Native Americans in a grand meal during the autumn of 1621.

But for the Pilgrims, what we today know as Thanksgiving was not a feast; rather, it was a spiritual devotion. Thanksgiving was a solemn and not a celebratory occasion. It was not a holiday.

Still, Plymouth was dominated by the 65 strangers, who were largely disinterested in what Pilgrims saw as urgent questions of their own eternal salvation.

There were few Protestant clerics among the Pilgrims, and in few short years, they found themselves to be what historian Mark Peterson calls “spiritual orphans.” Lay Pilgrims like William Brewster conducted services, but they were unable to administer Puritan sacraments.

Pilgrims and Native Americans in the 1620s

At the same time, Pilgrims did not actively seek the conversion of Native Americans. According to scholars like Philbrick, English author Rebecca Fraser and Peterson, the Pilgrims appreciated and respected the intellect and common humanity of Native Americans.

An early example of Pilgrim respect for the humanity of Native Americans came from the pen of Edward Winslow. Winslow was one of the chief Pilgrim founders of Plymouth. In 1622, just two years after the Pilgrims’ arrival, he published in the mother country the first book about life in New England, “Mourt’s Relation.”

While opining that Native Americans “are a people without any religion or knowledge of God,” he nevertheless praised them for being “very trusty, quick of apprehension, ripe witted, just.”

Winslow added that “we have found the Indians very faithful in their covenant of peace with us; very loving. … we often go to them, and they come to us; some of us have been fifty miles by land in the country with them.”

In Winslow’s second published book, “Good Newes from New England (1624),” he recounted at length nursing the Wampanoag leader Massasoit as he lay dying, even to the point of spoon-feeding him chicken broth.Fraser calls this episode “very tender.”

The Puritan exodus from England

Puritans barricading their house against Indians. Artist Albert Bobbett. The Print Collector/ Hudson Archives via Getty Images

The thousands of non-Pilgrim Puritans who remained behind and struggled in England would not share Winslow’s views. They were more concerned with what they saw as their own divine mission in America.

After 1628, dominant Puritan ministers clashed openly with the English Church and, more ominously, with King Charles I and Bishop of London – later Archbishop of Canterbury – William Laud.

So, hundreds and then thousands of Puritans made the momentous decision to leave England behind and follow the tiny band of Pilgrims to America. These Puritans never considered themselves separatists, though. Following what they were confident would be the ultimate triumph of the Puritans who remained in the mother country, they would return to help govern England.

The American Puritans of the 1630s and beyond were more ardent, and nervous about salvation, than the Pilgrims of the 1620s. Puritans tightly regulated both church and society and demanded proof of godly status, meaning evidence of a prosperous and virtuous life leading to eternal salvation. They were also acutely aware of that divine-sent mission to the New World.

Puritans believed they must seek out and convert Native Americans so as to “raise them to godliness.” Tens of thousands of Puritans therefore poured into Massachusetts Bay Colony in what became known as the “Great Migration.” By 1645, they already surrounded and would in time absorb the remnants of Plymouth Colony.

Puritans and Native Americans in the 1630s and beyond

Dominated by hundreds of Puritan clergy, Massachusetts Bay Colony was all about emigration, expansion and evangelization during this period.

As early as 1651, Puritan evangelists like Thomas Mayhew had converted 199 Native Americans labeled by the Puritans as “praying Indians.”

For those Native Americans who converted to Christianity and prayed with the Puritans, there existed an uneasy harmony with Europeans. For those who resisted what the Puritans saw as “God’s mission,” there was harsh treatment – and often death.

But even for those who succumbed to the Puritans’ evangelization, their culture and destiny changed dramatically and unalterably.

War with Native Americans

A devastating outcome of Puritan cultural dominance and prejudice was King Philip’s War in 1675-76. Massachusetts Bay Colony feared that Wampanoag chief Metacom – labeled by Puritans “King Philip” – planned to attack English settlements throughout New England in retaliation for the murder of “praying Indian” John Sassamon.

That suspicion mushroomed into a 14-month, all-out war between colonists and Native Americans over land, religion and control of the region’s economy. The conflict would prove to be one of the bloodiest per capita in all of American history.

By September 1676, thousands of Native Americans had been killed, with hundreds of others sold into servitude and slavery. King Philip’s War set an ominous precedent for Anglo-Native American relations throughout most of North America for centuries to come.

The Pilgrims’ true legacy

So, Puritans and Pilgrims came out of the same religious culture of 1570s England. They diverged in the early 1600s, but wound up 70 years later being one and the same in the New World.

In between, Pilgrim separatists sailed to Plymouth, survived a terrible first winter and convened a robust harvest-time meal with Native Americans. Traditionally, the Thanksgiving holiday calls to mind those first settlers’ courage and tenacity.

However, the humanity that Pilgrims like Edward Winslow showed toward the Native Americans they encountered was lamentably and tragically not shared by the Puritan colonists who followed them. Therefore, the ultimate legacy of Thanksgiving is and will remain mixed.

Michael Carrafiello is a professor of history at Miami University

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

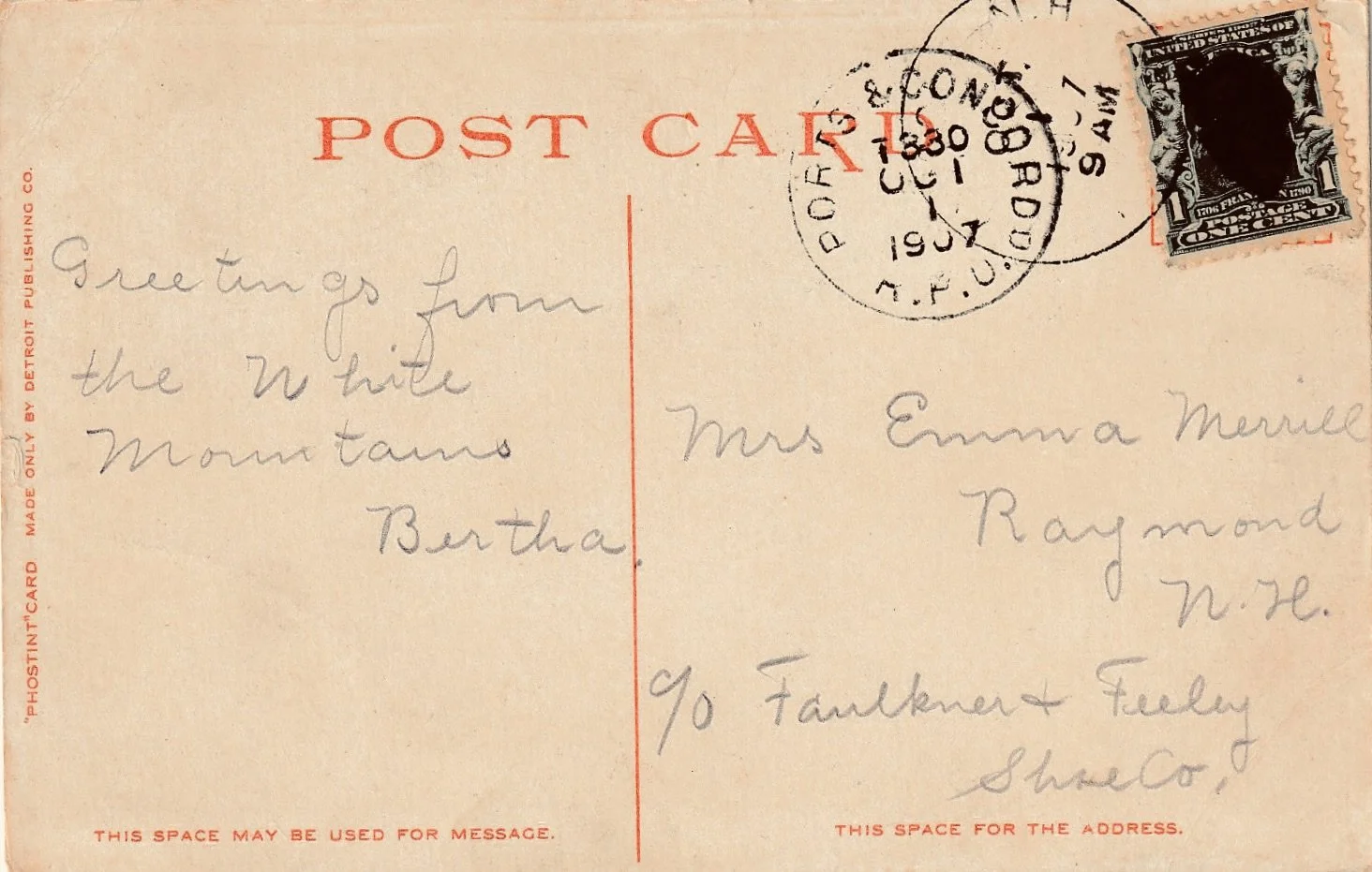

Shades of da Vinci

“Bird and Butterfly,’’ by the late Varujan Boghosian, in the show “Varujan Boghosian: Material Poetry,’’ at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass., through Dec. 22.

The museum explains that the show includes collages and mixed-media pieces that span Boghosian’s career, including rarely seen artworks from the collection of his daughter, Heidi Boghosian. “Well-known as an art professor at major American universities, Boghosian played a large role in the Provincetown art colony, influencing generations of artists and writers.’’

History teardown

"The intact facade's now almost black

in the rain; all day they've torn at the back

of the building, "the oldest concrete structure

in New England," the newspaper said...''— From “Demolition,’’ by Mark Doty (born 1953), American poet and memoirist

— From “Days of Me,’’ by Stuart Dischell

James T. Brett: Priorities for our region in the lame-duck Congress

BOSTON

After a long and brutally divisive election season, Congress now returns to Capitol Hill for the final weeks of the 118th Congress, AKA its ‘‘lame-duck session.” After an historically unproductive two years, their to-do list remains long.

However, a looming Dec. 20 deadline to pass legislation to continue to fund the government presents an opportunity to incorporate a variety of other pieces of legislation.

There are three proposals in particular that the New England Council, which I lead, believes are critical to economic prosperity and quality of life in the region, and remain our top legislative priorities for the remainder of 2024.

Extending telehealth flexibilities. Congress recognized the critical role of telehealth in health care delivery by expanding coverage during and after the COVID-19 public health emergency. Most recently, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 extended several Medicare telehealth flexibilities through Dec. 31, 2024.

Among these was a provision allowing patients to use telehealth regardless of where they are located. These short-term extensions have been important to expand access and ensure continuity of care. We know that telehealth has been particularly beneficial in ensuring access to much-needed behavioral health services, and has enabled patients in rural and underserved areas to receive quality health care services.

However, without Congressional action, these flexibilities will expire at year’s end. Fortunately, the House Energy & Commerce Committee has advanced bipartisan legislation that will extend these flexibilities for another two years. The New England Council supports this extension, and encourages Congress to consider making these flexibilities permanent.

Affordable connectivity program. Established by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed in late 2021, the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) ensures that all Americans have access to high-speed internet, which has become vital to economic success in the 21st century.

Administered by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the ACP provided a monthly subsidy of $30 for eligible households to use for broadband Internet. It also provided a one-time $100 benefit toward the purchase of a tablet, laptop or other device that facilitates Internet access.

Since its launch in Dec. 2021, the ACP helped more than 23 million American households gain access to affordable broadband, including over 800,000 across New England. Unfortunately, funding for the program ran out in April 2024. Bipartisan legislation has been introduced to infuse another $7 billion into the program, and we are hopeful that this provision will be included in any year-end spending package so that we do not lose ground in the effort to ensure digital equity for all Americans.

eDelivery. A third top priority for the lame-duck session is passage of legislation that would make electronic delivery (“eDelivery”) of financial statements and disclosures the default method of delivery to investors. Bipartisan legislation passed the House earlier this year as part of a larger capital markets package, but has languished in the Senate.

Not only is eDelivery more environmentally friendly as it decreases paper usage and waste, but it is also a much more secure and efficient method for delivering sensitive financial information to investors — particularly amid widespread reports of postage delays and the thefts. Perhaps most importantly, eDelivery is preferred by consumers.

A July 2022 survey conducted by the Securities Information and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) found that 79% of retail investors already participate in eDelivery programs, and 85% are comfortable with eDelivery being the default. Congress should heed their constituents and include this practical update in any year-end package.

All three of these proposals represent common-sense solutions, and perhaps more importantly, they all have strong bipartisan support. The New England Council will continue to urge our leaders in Washington to consider these proposals as key deadlines to advance legislation fast approach.

We believe that including these three proposals in any year-end legislative package will have a tremendous positive impact on individual New Englanders, as well as our region’s economic well-being.

James T. Brett is president and chief executive of the New England Council.

Linda Gasparello: Peripatetic Thanksgings

Marshes on Tangier Island. They are a major reason that seafood is usually so plentiful there.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Taking to the road over Thanksgiving is an American tradition, and AAA projects that a record 71.1 million Americans will drive to their dinner destination.

My husband and I will join the driving throngs. But our Thanksgiving tradition is to set out for no particular dinner destination and with no expectations. Over the years, we have had the best of dines and the worst of dines at restaurants where we have just walked in.

The Ram’s Head Tavern, in Annapolis, Md., is at the top of our Thanksgiving spins chart.

One year, as walk-ins, we enjoyed the tavern’s clubby conviviality and its Chesapeake Bay seafood-laden Thanksgiving menu, which included oyster stew and oyster stuffing. I share H.L. Mencken’s passion for large Maryland oysters, which he described as "magnificent, matchless reptiles" and a "thing of prolonged and kaleidoscopic flavors.”

Another Thanksgiving spin, in my husband’s Cessna 182RG, to Tangier Island, we rank at the bottom of our holiday dinners, mostly because no dining happened.

We flew from Dulles International Airport, in northern Virginia, to the island in the Chesapeake Bay, off the coast of Virginia, with a friend of ours who is also a pilot. Mike was always up for a flying adventure. To our knowledge, he had no reverence for food — it was just fuel, like Avgas for a plane.

It was my first trip to Tangier Island. I had read that some of the 600 inhabitants of the island spoke with the Elizabethan accent of its founders. We didn’t encounter any of them or, for that matter, anyone.

After we landed at the airport, which seemed to be unattended, we started walking to the town center.

Along the way, we passed a house surrounded with a chain-link fence. A Siberian Husky stood in the front yard. My husband and I owned one — he was a friendly fellow, a breed trait.

He called to the husky and put his fingers through the fence to pet him. The brute nearly made a Thanksgiving dinner of them.

When we reached the town, none of the restaurants were open; so no Maryland crab soup, no crab cakes, called “world famous” on Chesapeake Bay restaurant menus.

On our walk back to the airport, I grabbed a few crab recipes, printed on small squares of paper, which are left in boxes in front of some houses. One of them, “Daddy’s Crab Salad,” has an intriguing endnote: “The secret of this recipe is not what’s not in it. Let the crabmeat be the main ingredient.”

We flew to Washington National Airport, not because our stomachs were empty but because we were nearly out of fuel. The pumps at the island’s airport were on holiday, too.

We filled the plane’s two tanks at National and flew to Dulles, the plane’s base. Then we drove home, wondering if we had enough milk in the refrigerator for a bowl of cereal dinner.

Our neighbors saw us pull into our driveway and called to see if we wanted some pie. Did we ever! We ate all kinds of pies for dinner, and we gave thanks for all the good, sweet things and the family love that went into making them.

Linda Gasparello is producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Her email is lgasparello@kingpublishing.com and she’s based in Rhode Island.

Red, white and green

In Shrewsbury, Mass.

The Bartlett barn in Redding, Conn.

“{New England villages} are one of the great sights of the Western World — red buildings to house the cattle, white ones to hold the spirit, and trees like the spirit itself abroad in the countryside.’’

— Jane Langton, in “New England Classic,’’ in New England: The Four Seasons (1980)

Water and sand make art for beachcombers

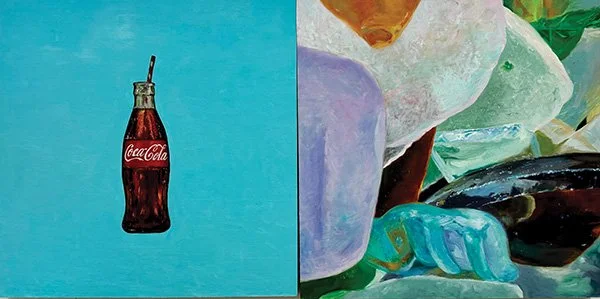

“Coke to Seaglass” (oil on wood), by Diane Athey, in the group show “Elemental,’’ at Mad River Valley Arts, Waitsfield, Vt. through Dec. 19.

The gallery explains:

“Elemental’ is about water and its soulful impact on our daily lives. Artists share the ethereal beauty of water and ask us to reflect upon our deep connection to this element of nature. Unusual materials and whimsical forms in their varying creative practices force the viewer to contemplate colors, textures, and emotions of imaginal landscapes, and to evoke the connection between them through the balance of harmony and disharmony, structure and chaos and the dance between light and shadow.’’