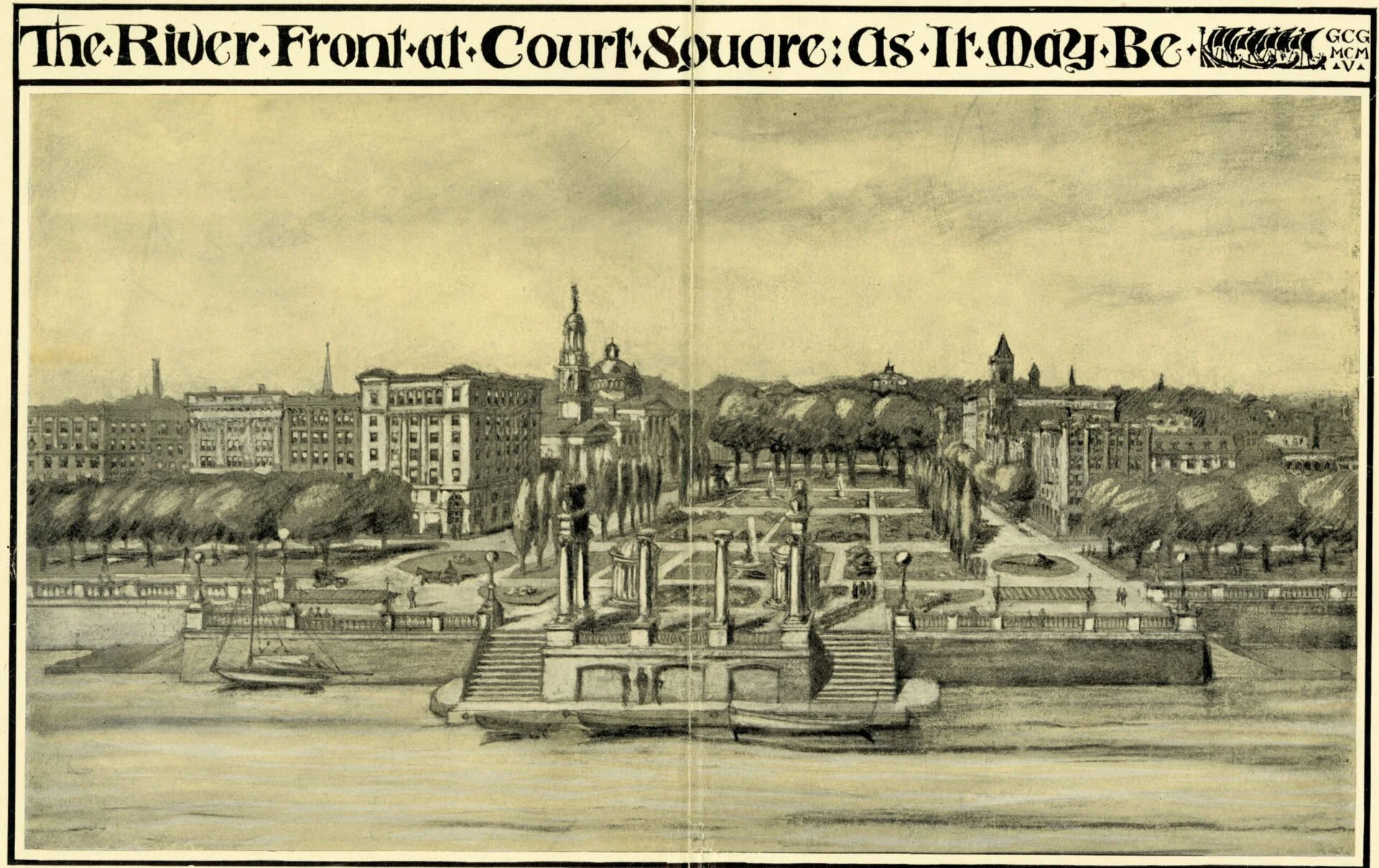

Designing Springfield's downtown through the years

From the “Designing Downtown” show at the Wood Museum of Springfield (Mass.) History through March 30.

The museum explains:

“Explore the history of downtown Springfield through centuries of plans that were never brought to fruition. Maps, drawings, blueprints, and more documents created by local citizens and nationally known city planners offer a glimpse into Springfield as it could have been and, at the same time, how the modern city came to be.

“Visitors can recreate a 1908 vote on the design of City Hall and can explore renowned landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.’s plan for a ‘Washington Mall’-inspired design for Court Square in expanded detail using touchscreen technology. Visitors will leave the exhibition with a new appreciation for the shape of Springfield, with an eye towards its future development as the city continues to expand.’’

UMaine is looking into creating public medical school to address rural physician shortage

Edited from a New England Council report

“The University of Maine System has announced it will work with a national consultant to examine the viability of launching the state’s first public medical school in response to a critical shortage of physicians in rural Maine.

“This concept has gained support from several associations, and UMS received state funding last year to undertake the study. The study comes as Maine’s only medical school—the University of New England’s College of Osteopathic Medicine—prepares to relocate from Biddeford to a newly expanded campus in Portland.

“‘The University of New England is always eager to partner with our colleagues at the University of Maine System and is proud of the mutually beneficial partnerships we have established with the system,’ said James Herbert, UNE’s president.’’

Read more in Mainebiz.

George J. Annas: Nuremberg code not just for Nazis

Nazi defendants at the Nuremberg trials

BOSTON

After World War II, Nuremberg, Germany, was the site of trials of Nazi officials charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Nuremberg trials were landmarks in the development of international law. But one of them has also been applied in peacetime: the “Medical Trial,” which has helped to shape bioethics ever since.

Twenty Nazi physicians and three administrators were tried for committing lethal and torturous human experimentation, including freezing prisoners in ice water and subjecting them to simulated high-altitude experiments. Other Nazi experiments included infecting prisoners with malaria, typhus and poisons and subjecting them to mustard gas and sterilization. These criminal experiments were conducted mostly in the concentration camps and often ended in the death of the subjects.

Lead prosecutor Telford Taylor, an American lawyer and general in the U.S. Army, argued that such deadly experiments were more accurately classified as murder and torture than anything related to the practice of medicine. A review of the evidence, including physician expert witnesses and testimony from camp survivors, led the judges to agree. The verdicts were handed down on Aug. 20, 1947.

As part of their judgment, the American judges drafted what has become known as The Nuremberg Code, which set forth key requirements for ethical treatment and medical research. The code has been widely recognized for, among other things, being the first major articulation of the doctrine of informed consent. Yet its guidelines may not be enough to protect humans against new potentially “species-endangering” research today.

The code consists of 10 principles that the judges ruled must be followed as both a matter of medical ethics and a matter of international human rights law.

The first and most famous sentence stands out: “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.”

In addition to voluntary and informed consent, the code also requires that subjects have a right to withdraw from an experiment at any time. The other provisions are designed to protect the health of the subjects, including that the research must be done only by a qualified investigator, follow sound science, be based on preliminary research on animals and ensure adequate health and safety protection of subjects.

The trial’s prosecutors, physicians and judges formulated the code by working together. As they did, they also set the early agenda for a new field: bioethics. The guidelines also describe a scientist-subject relationship that obligates researchers to do more than act in what they think is the best interests of subjects, but to respect the subject’s human rights and protect their welfare. These rules essentially replace the paternalistic model of the Hippocratic oath with a human rights approach.

Four Polish women, including survivors of human experiments at concentration camps, arrive to serve as witnesses for the prosecution at the Doctors Trial. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum via Wikimedia Commons

Under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had been the commanding general in Europe, the U.S. Department of Defense adopted the code’s principles in 1953 – one sign of its influence. Its fundamental consent principle is also summarized in the U.N.’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which declares that “no one shall be subjected without his free consent to medical or scientific experimentation.”

Yet some physicians tried to distance themselves from the Nuremberg Code because its source was judicial rather than medical, and because they did not want to be linked in any way to the Nazi physicians on trial at Nuremberg.

The World Medical Association, a physicians group set up after the Nuremberg Doctors Trial, formulated its own set of ethical guidelines, named the “Helsinki Declaration.” As with Hippocrates, Helsinki permitted exceptions to informed consent, such as when the physician-researcher thought that silence was in the best medical interest of the subject.

The Nuremberg Code was written by judges to be applied in the courtroom. Helinski was written by physicians for physicians.

There have been no subsequent international trials on human experimentation since Nuremberg, even in the International Criminal Court, so the text of the Nuremberg Code remains unchanged.

New research, new procedures?

The code has been a major focus of my work on health law and bioethics, and I spoke in Nuremberg on its 50th and 75th anniversaries, at conferences sponsored by the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. Both events celebrated the Nuremberg Code as a human rights proclamation.

Jadwiga Kaminska, who survived Ravensbruck concentration camp, testifies about the experimental operations she was forced to undergo there. Office of Military Government for Germany (U.S.) via Wikimedia Commons

I remain a strong supporter of the Nuremberg Code and believe that following its precepts is both an ethical and a legal obligation of physician researchers. Yet the public can’t expect Nuremberg to protect it against all types of scientific research or weapons development.

Soon after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki – two years before the Nuremberg trials began – it became evident that our species was capable of destroying ourselves.

Nuclear weapons are only one example. Most recently, international debate has focused on new potential pandemics, but also on “gain-of-function” research, which sometimes adds lethality to an existing bacteria or virus to make it more dangerous. The goal is not to harm humans but rather to try to develop a protective countermeasure. The danger, of course, is that a super harmful agent “escapes” from the laboratory before such a countermeasure can be developed.

I agree with the critics who argue that at least some gain-of-function research is so dangerous to our species that it should be outlawed altogether. Innovations in artificial intelligence and climate engineering could also pose lethal dangers to all humans, not just some humans. Our next question is who gets to decide whether species-endangering research should be done, and on what basis?

I believe that species-endangering research should require multinational, democratic debate and approval. Such a mechanism would be one way to make the survival of our own endangered species more likely – and ensure we are able to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Nuremberg Code.

George J .Annas is director of the Center for Health Law, Ethics & Human Rights at Boston University.

George J. Annas does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

e

Dirty work

Patricia Rangel at work creating am abstract landscape. She's in the group show "Through Line,'' at the Lamont Gallery, in Exeter, N.H., Sept. 5-Nov. 23

The gallery says:

“Rangel responds to dirt as a material that can present vulnerability, failure, strength, and potential to promote growth and change. The structures she creates are composed of dirt and found materials from places that hold significance. For her, the intersecting and overlapping of lines in this work acts as a metaphor for navigating complex emotions and the potential and opportunity for growth.

xxx

“‘Through Line’ celebrates basic mark-making as a foundation for the remarkable. Each of the six artists on view explores line through the lens of their distinct practices and mediums, ranging from marker to string, chalk, and even dirt! Together, they apply their shared interest in using lines as the basis for their work to boldly illustrate how understated, rudimentary marks can be explored more deeply. Collectively, the artworks on view act as tributes to the mark, celebrating the multitude of ways lines can be made, manipulated, and made monumental.’’

Wired for art

"Gail" (photogravure), by Liz Shepherd, in her show "Look Don't Look,'' at Boston Sculptors Gallery, through Sept. 29.

-- Image courtesy of the gallery

The gallery says the show features a collection of wearable wire sculptures “designed to both conceal and emphasize the person wearing them.’’ Artist Liz Shepherd invited 10 friends "of a certain age" to sit for portraits wearing the wire sculptures. “I wanted to see if their attitude about their appearance might be influenced by the experience of wearing an unusual, often flamboyant, object," she said. The exhibit also includes silkscreen images of the sculptures printed on mirrors so that visitors can view themselves through the lens of the artwork.

Chris Powell: Too much higher ed?

The precursor to the University of Connecticut in 1903.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

What a wonderfully subversive and politically incorrect idea has exploded from the committee set up by the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities to study the problem of the state's estimated 119,000 "disconnected" and alienated young people.

Meeting last week at New London City Hall, the group heard a vice president of Yale New Haven Health, Paul Mounds Jr., criticize the widespread misimpression that hospitals and other medical companies hire only applicants with college degrees.

Mounds said Connecticut's hospitals have hundreds of openings for people with high school diplomas or the equivalent. He added that employers should reach out to overlooked potential workers, including former convicts. (A decent job is a strong incentive not to return to crime.)

The president of the Connecticut Business and Industry Association, Chris DiPentima, elaborated. He said many of Connecticut's reported 93,000 job openings don't require college degrees and he urged employers to shift from degree-based hiring to skill-based hiring. DePentima scorned what he called efforts to "over-educate the population."

That is, Mounds and DiPentima were lamenting the cost of the credentialism that has been inflicted on society by higher educators, who profit greatly from it, and by society's own vanity. (See "Doctor" Jill Biden.) Credentialism is why millions of Americans are hobbled with billions of dollars of college-loan debt incurred in pursuit of degrees that conferred little in the way of education or job skills.

Of course, credentialism is a big business in itself, as shown by a review of salaries in higher education, especially administrator salaries. Reducing credentialism might cause a fair amount of unemployment, since much of higher education is just unnecessary overhead expense for society.

Higher education isn't useless. But outside highly technical fields, it is grossly overpriced and distracts catastrophically from the country's big education problem, lower education.

A recent survey by the Connecticut Education Association, the state's largest teacher union, illustrated a big part of the lower-education problem.

It wasn't the survey's finding that teachers in Connecticut say they are underpaid. As they are members of unions it's practically their obligation to feel underpaid, just as they felt underpaid in 1986 when the state's Education Enhancement Act became law, leading to decades of steady pay increases for teachers in the belief that student performance was mainly a function of teacher salaries. (There turned out to be no connection, and student performance has declined as teacher pay has risen.)

No, the CEA survey was valuable for showing that teachers are increasingly demoralized by student misbehavior, which is prompting teachers to leave their profession earlier than planned and making it harder for schools to hire good applicants.

This problem is worst where poverty, child neglect, and mental illness among children are worst -- cities and inner suburbs. While Hartford's school superintendent, Leslie Torres-Rodriguez, showed her usual enthusiasm in welcoming children back to school this week, she also acknowledged that the city's schools are still trying to fill 200 vacant positions. As the CEA survey indicated, teachers want to teach, not break up brawls or restrain children who freak out in class and don't know how to behave because they have so little parenting -- and because school administrations prohibit disciplining them.

This social disintegration is part of government's general impoverishment of society but Connecticut's political class remains oblivious to it and busies itself instead with politically correct irrelevance, as New Haven's city council did the other day even as the city's schools are just as dismal as Hartford's.

The council is promoting a resolution that would apologize for New Haven's having blocked the establishment of a college for Black people back in 1831, nearly two centuries ago.

Maybe in another two centuries New Haven will apologize for the failure of most of its schoolchildren to perform even close to grade level, for the racial achievement gap in its schools, and for the city's constant crime, most of whose victims are members of minority groups. Maybe in two centuries state government will consider apologizing too.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Exploring Shaker art and their ‘three C’s’

"Red Cloak Blue Bucket" (water color and dry brush on paper), by Barbara Ernst Prey, in the show "Handled With Care: Shaker Master Crafts and the Art of Barbara Prey,'' at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art through Feb. 9

The museum says this is part of a collaboration with Hancock Shaker Village.

“This year, we celebrate the 250th anniversary of The United Society of Believers, more commonly called Shakers, in America. This current exhibition continues the series of ‘Masterworks of Shaker Design’ by recognizing a special dimension of the Shakers’ work: their finely crafted, and now beautifully preserved, small crafts. Once despised and persecuted for their beliefs of Communal ownership of all goods and property, Confession of sins in private, and Celibacy—the ‘three C’s—most people now adore so much about the Shakers. This love certainly extends to their long handcraft tradition.

“We also celebrate the achievements of the world-renowned contemporary artist Barbara Ernst Prey. Barbara accepted a commission from Hancock Shaker Village, in the Berkshires, in 2018-2019, to execute a series of large-scale paintings in watercolor and dry brush of any subject that engaged her attention and admiration. Her subject turned out to be both as simple and as complex as the interplay of natural light and Hancock’s built environment.’’

The Round Barn at Hancock Shaker Village.

Llewellyn King: How nimbyism is strangling America

Sign in Minneapolis opposing ending single-family zoning., which happened after years of legal challenges.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Like fog, it creeps in, but unlike fog, it doesn’t dissipate. It gets denser and does untold damage to the economy and to the lives of Americans.

It is that modern plague, known as much by its acronym as by its phrase: NIMBY, “not in my backyard.” It is the mantra of everyone who wants wherever they are to remain as it is — in perpetuity.

It is behind, in part, the crisis in electricity transmission, the lack of much-needed natural gas and oil pipelines, unbuilt but needed highways, and is a player in environmental injustice.

NIMBYism has also contributed to the housing crisis. It makes it so hard to build anything that disturbs the serenity of those who live in leafy suburbs with manicured lawns, and, perhaps, designer dogs. Yes, people like me — even though I can’t afford one of those homes or dogs.

If you are living the American Dream — two cars, swell house, well-tended garden — you are almost certainly a passive NIMBY contributor.

Active NIMBYs, abetted by the local ordinances that make life pleasant for the urban and suburban elites, fear that new housing will bring things they abhor: traffic, crowding, pollution and people of a different social class.

Desperately needed apartments and even mother-in-law houses or extensions are denied, contributing substantially to the national housing crisis.

It is easy to identify the impact of NIMBYism in housing, but it is at work across America, restricting, redirecting and forcing the abandonment of projects.

Power lines aren’t constructed, natural gas isn’t moved, road plans are abandoned and such unwanted facilities as prisons, factories and slaughterhouses are inflicted on poor areas, often rural, where the locals are bribed with job promises or don’t have the sophistication or resources to build opposition with media, litigation and political influence.

In Rhode Island, in the last several years, I have seen opposition mounted against a fish farm, offshore windmills, a medical-waste-disposal facility and various housing developments. “Put it somewhere else” is the collective cry.

So the medical-waste facility will go to an area where residents are less likely to object, not where it is needed, adding transportation costs; the power will be generated somewhere else or there will be a shortfall; and Rhode Islanders, under a modified plan, may eventually get oysters farmed in the Sakonnet River.

The distorting effects of NIMBYism aren’t just an American burden. In Europe, they are as bad or worse.

The Economist has been writing for a long time about how hidebound Britain has become by the prevalence of a culture of “don’t change anything.” The magazine has often pointed out that Britain has become a place where it is impossible to get anything done.

I can attest to that. A family member lived in a not very impressive — actually ugly — apartment block, built in the 1930s, near London.

As was done at that time to save money, all the water and sewer pipes were external, running along the walls on the outside. I only mention the pipes to point out that this building wasn’t lovely or a significant piece of English architecture, it was just a utilitarian block of flats. Yet, local ordinances, designed to preserve the historic and beautiful buildings, prohibited the residents from replacing older, leaky, wood-framed windows with modern, metal-framed windows. Preservation run amok is stultifying.

Not every project — either big, such as a power plant, or small, like an apartment adjoining a house for an aging relative — is right for a community. But when local selfishness transcends a national need, some revision is needed.

Certainly industrial companies, real-estate developers and utilities shouldn’t be entitled to overrule local people axiomatically, but when the national interest is held hostage to local preference, there is a problem.

Take the long-planned and abandoned after completion nuclear waste storage site in Yucca Mountain, Nev. It was abandoned because of well-orchestrated opposition. Result: nuclear waste is now temporarily stored above ground, near where it is created — as much a product of NIMBYism as the housing shortage.

The British have another acronym for what happened to Yucca Mountain: DADA, “decide, announce, defend, abandon.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Good reason to drive with windows open

Quotes from Cambridge, Mass.-based Tom Magliozzi (1937-2014).

He and his brother Ray Magliozzi (1949) were the co-hosts of NPR's weekly radio show Car Talk, where they were known as "Click and Clack, the Tappet Brothers".

“If money can fix it, it’s not a problem.’’

"Some guy I met said it's amazing how we use cars on our show as an excuse to discuss everything in the world—energy, psychology, behavior, love, money, economics and finance. The cars themselves are boring as hell."

“It is better to travel in hope than arrive in despair.”

"If it falls off, it doesn't matter.”

"I like to drive with the windows open. I mean, before you know it, you're going to spend plenty of time sealed up in a box anyway, right?”

Between water and sun

“Ocean Moon” (woodcut), by Mary Mead, in the group show ‘‘between water and sun,’’ at AVA Gallery, Lebanon, N.H., through Oct. 5

(Image courtesy of AVA Gallery)

The gallery explains that the show displays the work of 33 artists “who explore the often-overlooked space between the water and the sun. This theme was completely open to interpretation by artists who submitted work in all mediums from photography to painting and everything in between. No artist approached the theme in the same way.’’

Mini and malleable monuments

From Massachusetts artist Dianne Pappas’s show “mini monuments’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery through Sept. 29

The gallery notes her “constructed compositions of symbols, lines, tallies, maps, markings, and characters. Fiberfill, vitamin capsules, rubber mold, tarlatan, clay, wire, masking paper, resin, corrugated metal, hangers, reflective mylar, and bubble gum are comforting, regimented, bouncy, accepting, foundational, transparent, shiny, supportive, distorted, and tasty. Pappas ponders the questions: What do we want our monuments to do? What do we need our monuments to do?’’

Fred Schulte: Medicare Advantage corruption in action

From Kaiser Family Health News

“CMS saving money for taxpayers isn’t enough of a reason to face the wrath of very powerful health plans.’’

Erin Fuse Brown, professor at the Brown University School of Public Health, in Providence

A decade ago, federal officials drafted a plan to discourage Medicare Advantage health insurers from overcharging the government by billions of dollars — only to abruptly back off amid an “uproar” from the industry, newly released court filings show.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services published the draft regulation in January 2014. The rule would have required health plans, when examining patient’s medical records, to identify overpayments by CMS and refund them to the government.

But in May 2014, CMS dropped the idea without any public explanation. Newly released court depositions show that agency officials repeatedly cited concern about pressure from the industry.

The 2014 decision by CMS, and events related to it, are at the center of a multibillion-dollar Justice Department civil fraud case against UnitedHealth Group pending in federal court in Los Angeles.

The Justice Department alleges the giant health insurer cheated Medicare out of more than $2 billion by reviewing patients’ records to find additional diagnoses, adding revenue while ignoring overcharges that might reduce bills. The company “buried its head in the sand and did nothing but keep the money,” DOJ said in a court filing.

Medicare pays health plans higher rates for sicker patients but requires that the plans bill only for conditions that are properly documented in a patient’s medical records.

In a court filing, UnitedHealth Group denies wrongdoing and argues it shouldn’t be penalized for “failing to follow a rule that CMS considered a decade ago but declined to adopt.”

This month, the parties in the court case made public thousands of pages of depositions and other records that offer a rare glimpse inside the Medicare agency’s long-running struggle to keep the private health plans from taking taxpayers for a multibillion-dollar ride.

“It’s easy to dump on Medicare Advantage plans, but CMS made a complete boondoggle out of this,” said Richard Lieberman, a Colorado health data analytics expert.

Spokespeople for the Justice Department and CMS declined to comment for this article. In an email, UnitedHealth Group spokesperson Heather Soule said the company’s “business practices have always been transparent, lawful and compliant with CMS regulations.”

Missed Diagnoses

Medicare Advantage insurance plans have grown explosively in recent years and now enroll about 33 million members, more than half of people eligible for Medicare. Along the way, the industry has been the target of dozens of whistleblower lawsuits, government audits, and other investigations alleging the health plans often exaggerate how sick patients are to rake in undeserved Medicare payments — including by doing what are called chart reviews, intended to find allegedly missed diagnosis codes.

By 2013, CMS officials knew some Medicare health plans were hiring medical coding and analytics consultants to aggressively mine patient files — but they doubted the agency’s authority to demand that health plans also look for and delete unsupported diagnoses.

The proposed January 2014 regulation mandated that chart reviews “cannot be designed only to identify diagnoses that would trigger additional payments” to health plans.

CMS officials backed down in May 2014 because of “stakeholder concern and pushback,” Cheri Rice, then director of the CMS Medicare plan payment group, testified in a 2022 deposition made public this month. A second CMS official, Anne Hornsby, described the industry’s reaction as an “uproar.”

Exactly who made the call to withdraw the chart review proposal isn’t clear from court filings so far.

“The direction that we received was that the rule, the final rule, needed to include only those provisions that had wide, you know, widespread stakeholder support,” Rice testified.

“So we did not move forward then,” she said. “Not because we didn’t think it was the right thing to do or the right policy, but because it had mixed reactions from stakeholders.”

The CMS press office declined to make Rice available for an interview. Hornsby, who has since left the agency, declined to comment.

But Erin Fuse Brown, a professor at the Brown University School of Public Health, said the decision reflects a pattern of timid CMS oversight of the popular health plans for seniors.

“CMS saving money for taxpayers isn’t enough of a reason to face the wrath of very powerful health plans,” Fuse Brown said.

“That is extremely alarming.”

Invalid Codes

The fraud case against UnitedHealth Group, which runs the nation’s largest Medicare Advantage plan, was filed in 2011 by a former company employee. The DOJ took over the whistleblower suit in 2017.

DOJ alleges Medicare paid the insurer more than $7.2 billion from 2009 through 2016 solely based on chart reviews; the company would have received $2.1 billion less if it had deleted unsupported billing codes, the government says.

The government argues that UnitedHealth Group knew that many conditions it had billed for were not supported by medical records but chose to pocket the overpayments. For instance, the insurer billed Medicare nearly $28,000 in 2011 to treat a patient for cancer, congestive heart failure, and other serious health problems that weren’t recorded in the person’s medical record, DOJ alleged in a 2017 filing.

In all, DOJ contends that UnitedHealth Group should have deleted more than 2 million invalid codes.

Instead, company executives signed annual statements attesting that the billing data submitted to CMS was “accurate, complete, and truthful.” Those actions violated the False Claims Act, a federal law that makes it illegal to submit bogus bills to the government, DOJ alleges.

The complex case has featured years of legal jockeying, even pitting the recollections of key CMS staff members — including several who have since departed government for jobs in the industry — against those of UnitedHealthcare executives.

‘Red Herring’

Court filings describe a 45-minute video conference arranged by then-CMS administrator Marilyn Tavenner on April 29, 2014. Tavenner testified she set up the meeting between UnitedHealth and CMS staff at the request of Larry Renfro, a senior UnitedHealth Group executive, to discuss implications of the draft rule. Neither Tavenner nor Renfro attended.

Two UnitedHealth Group executives on the call said in depositions that CMS staffers told them the company had no obligation at the time to uncover erroneous codes. One of the executives, Steve Nelson, called it a “very clear answer” to the question. Nelson has since left the company.

For their part, four of the five CMS staffers on the call said in depositions that they didn’t remember what was said. Unlike the company’s team, none of the government officials took detailed notes.

“All I can tell you is I remember feeling very uncomfortable in the meeting,” Rice said in her 2022 deposition.

Yet Rice and one other CMS staffer said they did recall reminding the executives that even without the chart review rule, the company was obligated to make a good-faith effort to bill only for verified codes — or face possible penalties under the False Claims Act. And CMS officials reinforced that view in follow-up emails, according to court filings.

DOJ called the flap over the ill-fated regulation a “red herring” in a court filing and alleges that when UnitedHealth asked for the April 2014 meeting, it knew its chart reviews had been under investigation for two years. In addition, the company was “grappling with a projected $500 million budget deficit,” according to DOJ.

Data Miners

Medicare Advantage plans defend chart reviews against criticism that they do little but artificially inflate the government’s costs.

“Chart reviews are one of many tools Medicare Advantage plans use to support patients, identify chronic conditions, and prevent those conditions from becoming more serious,” said Chris Bond, a spokesperson for AHIP, a health insurance trade group.

Whistleblowers have argued that the cottage industry of analytics firms and coders that sprang up to conduct these reviews pitched their services as a huge moneymaking exercise for health plans — and little else.

“It was never legitimate,” said William Hanagami, a California attorney who represented whistleblower James Swoben in a 2009 case that alleged chart reviews improperly inflated Medicare payments. In a 2016 decision, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals wrote that health plans must exercise “due diligence” to ensure they submit accurate data.

Since then, other insurers have settled DOJ allegations that they billed Medicare for unconfirmed diagnoses stemming from chart reviews. In July 2023, Martin’s Point Health Plan, a Portland, Maine, insurer, paid $22,485,000 to settle whistleblower allegations that it improperly billed for conditions ranging from diabetes with complications to morbid obesity. The plan denied any liability.

A December 2019 report by the Health and Human Services Inspector General found that 99% of chart reviews added new medical diagnoses at a cost to Medicare of an estimated $6.7 billion for 2017 alone.

Fred Schulte is a Kaiser Family Foundation health news reporter.

Behind the art

“My Dad’s Detritus Granite Wall,’’ by Vermont-based artist Anthony Surratt, in the group show “Lineages: Artists Are Never Alone'', at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester, Vt., opening Oct. 5.

The center says:

‘‘‘Lineages’ showcases the unique voices and individual talents of 11 contemporary artists and constructs a compelling collective exposition on the diverse webs of influences and personal experiences that drive artistic expression. Spanning a multiplicity of styles, media, and points of view, the exhibition and supporting programs delve deep into the artists’ creative processes to celebrate not just their exhibited work but the powerful, enduring, yet often unseen inspirational forces behind the art.’’

Scott Taylor: The mystic and the mathematician

The Babylonian mathematical tablet, dated to 1800 B.C.

‘Waterville, Maine

Like most mathematicians, I hear confessions from complete strangers: the inevitable “I was always bad at math.” I suppress the response, “You are forgiven, my child.”

Why does it feel like a sin to struggle in math? Why are so many traumatized by their mathematics education? Is learning math worthwhile?

Sometimes agreeing and sometimes disagreeing, André and Simone Weil were the sort of siblings who would argue about such questions. André achieved renown as a mathematician; Simone was a formidable philosopher and mystic. André focused on applying algebra and geometry to deep questions about the structures of whole numbers, while Simone was concerned with how the world can be soul-crushing.

Both wrestled with the best way to teach math. Their insights and contradictions point to the fundamental role that mathematics and mathematics education play in human life and culture.

André Weil’s rigorous mathematics

André Weil, pictured here in 1956, was a prominent mathematician in the 20th century. Konrad Jacobs via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Unlike the prominent French mathematicians of previous generations, André, who was born in 1906 and died in 1998, spent little time philosophizing. For him, mathematics was a living subject endowed with a long and substantial history, but as he remarked, he saw “no need to defend (it).”

In his interactions with people, André was an unsparing critic. Although admired by some colleagues, he was feared by and at times disdainful of his students. He co-founded the Bourbaki mathematics collective that used abstraction and logical rigor to restructure mathematics from the ground up.

Nicolas Bourbaki’s commitment to proceeding from first principles, however, did not completely encapsulate his conception of what constituted worthwhile mathematics. André was attuned to how math should be taught differently to different audiences.

Tempering the Bourbaki spirit, he defined rigor as “(not) proving everything, but … endeavoring to assume as little as possible at every stage.”

The Bourbaki congress in 1938. Simone, pictured at front left, accompanies André, obscured at back left. Unknown author via Wikimedia Commons

In other words, absolute rigor has its place, but teachers must be willing to take their audience into account. He believed that teachers must motivate students by providing them meaningful problems and provocative examples. Excitement for advanced students comes in encountering the unknown; for beginning students, it emerges from solving questions of, as he put it, “theoretical or practical importance.” He insisted that math “must be a source of intellectual excitement.”

André’s own sense of intellectual excitement came from applying insights from one part of mathematics to other parts. In a letter to his sister, André described his work as seeking a metaphorical “Rosetta stone” of analogies between advanced versions of three basic mathematical objects: numbers, polynomials and geometric spaces.

André described mathematics in romantic terms. Initially, the relationship between the different parts of mathematics is that of passionate lovers, exchanging “furtive caresses” and having “inexplicable quarrels.” But as the analogies eventually give way to a single unified theory, the affair grows cold: “Gone is the analogy: gone are the two theories, their conflicts and their delicious reciprocal reflections … alas, all is just one theory, whose majestic beauty can no longer excite us.”

Despite being passionless, this theory that unifies numbers, polynomials and geometry gets to the heart of mathematics; André pursued it intensely. In the words of a colleague, André sought the “real meaning of every basic mathematical phenomenon.” For him, unlike his sister, this real meaning was found in the careful definitions, precisely articulated theorems and rigorous proofs of the most advanced mathematics of his time. Romantic language simply described the emotions of the mathematician encountering the mathematics; it did not point to any deeper significance.

Simone Weil and the philosophy of mathematics

On the other hand, Simone, who was born three years after André and died 55 years before him, used philosophy and religion to investigate the value of mathematics for nongeniuses, in addition to her work on politics, war, science and suffering.

Simone Weil, pictured here in 1925, was a prominent philosopher. Anonymous via Wikimedia Commons

All of her writing – indeed, her life – has a maddening quality to it. In her polished essays, as well as her private letters and journals, she will often make an extreme assertion or enigmatic comment. Such assertions might concern the motivations of scientists, the psychological state of a sufferer, the nature of labor, an analysis of labor unions or an interpretation of Greek philosophers and mathematicians. She is not a systematic thinker but rather circles around and around clusters of ideas and themes. When I read her writing, I am often taken aback. I start to argue with her, bringing up counterexamples and qualifications, but I eventually end up granting the essence of her point. Simone was known for the single-minded pursuit of her ideals.

Despite the discomfort her viewpoints provoke, they are worth engaging. Although her childhood was largely happy, her whole life she felt stupid in comparison with her brother. She channeled her feelings of inadequacy into an exploration of how to experience a meaningful existence in the face of oppression and affliction. Over her life, she developed an interpretation of beauty and suffering intertwined with geometry.

Along with her lifelong mathematical discussions with André, her views were influenced by one of her first jobs as a teacher. In a letter to a colleague, she described her pupils as struggling because they “regarded the various sciences as compilations of cut-and-dried knowledge.” Like André, Simone saw the ability to motivate students as the key to good teaching. She taught mathematics as a subject embedded in culture, emphasizing overarching historical themes. Even those students who were “most ignorant in science” followed her lectures with “passionate interest.”

For Simone, however, the primary purpose of mathematics education was to develop the virtue of attention. Mathematics confronts us with our mistakes, and the contemplation of these inadequacies brings the ability to concentrate on one thing, at the exclusion of all else, to the fore. As a math teacher, I frequently see students grit their teeth and furrow their brow, developing only a headache and resentment. According to Simone, however, true attention arises from joy and desire. We hold our knowledge lightly and wait with detached thought for light to arrive.

For Simone, the “first duty” of teachers is to help students develop, through their studies, the ability to apprehend God, which she conceptualized as a blending of Plato’s description of the ultimate Good with Christian conceptions of the self-abnegating God. A true understanding of God results in love for the afflicted.

Simone might even locate the lingering anxiety and frustration of many former math students in the absence of attention paid to them by their teachers.

Authors grapple with the Weil legacy

Recently, others have wrestled with the Weil legacy.

Sylvie Weil, André’s daughter, was born shortly before Simone’s death. Her family experience was that of being mistaken for her aunt, ignored or demeaned by her father and not being acknowledged and appreciated by those in her orbit.

Similarly, author Karen Olsson uses Simone and André to explore her own conflicted relationship with mathematics. Her forlorn quest to understand André’s mathematics eerily reflects Simone’s desire to understand André’s work and Sylvie’s desire to be seen as her own person, to not be in Simone’s shadow. Olsson studied with exceptional math teachers and students, all the while feeling out of place, overwhelmed and intimidated by her fellow students. Most painfully, in the process of writing her book on the Weil siblings, Olsson asks a mathematician, who had been a student with her, for help in understanding some aspect of André’s mathematics. She was ignored. Both Sylvie Weil and Karen Olsson are living witnesses to Simone’s observation that each of us cries out to be seen.

Christopher Jackson, on the other hand, gives testimony to how mathematics can live up to Simone’s vision. Jackson is incarcerated in a federal prison but found a new life through mathematics. His correspondence with mathematician Francis Su is the backbone of Su’s 2020 book “Mathematics for Human Flourishing,” which uses Simone’s observation that “every being cries out silently to be read differently” as a leitmotif. Su identifies aspects of mathematics that promote human flourishing, such as beauty, truth, freedom and love. In their own ways, both Simone and André would likely agree.

Scott Taylor is a professor of mathematics at Colby College in Waterville, Maine.

Disclosure statement

He receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the John and Mary Neff Foundation.

'Coursing through nature'

“Basin, Thoreau’s Remarkable Pothole’’ (digital achival print), by Tim Greenway, in his show “Tim Greenway: Waterways,’’ at Cove Street Art, Portland, Maine, through Sept. 28. (Image courtesy of Cove Street Art)

The gallery says the show uses photography to capture, in his words, "the peaceful yet powerful journey of water flowing from the untouched snowcaps of the White Mountains ... ultimately merging with the Maine coast." Tim Greenway's photography explores “the light, color and texture" of water coursing through nature.

‘Happy in a household calm’

Corridor 71, Spencer State Forest, Spencer, Mass. (Photo by John Phelan)

New England woods are fair of face,

And warm with tender, homely grace,

Not vast with tropic mystery,

Nor scant with arctic poverty,

But fragrant with familiar balm,

And happy in a household calm.

And such O land of shining star

Hitched to a cart! thy poets are,

So wonted to the common ways

Of level nights and busy days,

Yet painting hackneyed toll and ease

With glories of the Pleiades.

For Bryant is an aged oak,

Beloved of Time, and sober folk;

And Whittler, a hickory,

The workman's and the children's tree;

And Lowell is a maple decked

With autumn splendor circumspect.

Clear Longfellow's an elm benign,

With fluent grace in every line

And Holmes, the cheerful birch intent;

On frankest, whitest merriment

While Emerson's high councils rise;

A pine, communing with the skies.

— “New England Woods,’’ by Amos Russel Wells (1862-1933), American author, editor and professor. In this poem, corny to our ears, he cites some famous New England poets.

‘Sustainable art’ and tech

“Plastic Squirrel,’’ by Bordalo II, in the show “TRANSFORM: Reduce, Revive, Reimagine,'' at DATMA (Design, Art, Technology Massachusetts) in New Bedford.

DATMA says this a “public art series uniting sustainable art and cutting-edge technology. Lisbon street artist Bordalo II, known for his unique and impactful artwork that conveys powerful environmental messages, is showcasing an awe-inspiring, newly commissioned colorful animal sculpture called Plastic Rooster on view until 2029. Plus, a photography exhibition highlights technological innovations in robotics, marine research and exploration, and wind energy that are ushering in a transformative era for South Coast of Massachusetts. Additional public programs and workshops are available all summer. All exhibitions are outdoors, free and open to the public.’’

Nature-based ways to mitigate disasters

A coastal salt marsh in East Lyme, Conn., along Long Island Sound. Restoring coastal wetlands helps reduce the damage from storms and rising seas associated with global warming. (Photo by Alex756 )

Excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini

“A new global assessment of scientific literature led by researchers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst found that nature-based solutions (NBS) are an economically effective method to mitigate risks from a range of disasters, including floods, hurricanes, and heat waves — all which are expected to intensify as the planet continues to warm.

“NBS solutions are interventions where an ecosystem is either preserved, sustainably managed, or restored to provide benefits to society and to nature. For instance, they can mitigate risk from a natural disaster, or facilitate climate mitigation and adaptation. They have emerged in combination with or as an alternative to engineering-based solutions, such as restoring wetlands to address coastal flooding rather than building a seawall.’’

The rise of Pittsfield

Downtown Pittsfield, Mass., in 2014

Pittsfield has in the past few years come to be called the “Brooklyn of The Berkshires” because its gentrifying neighborhoods and innovative arts programs are to the Berkshires’ more upmarket towns, such as Lenox, as a certain outer borough is to Manhattan.

‘Outside observer’

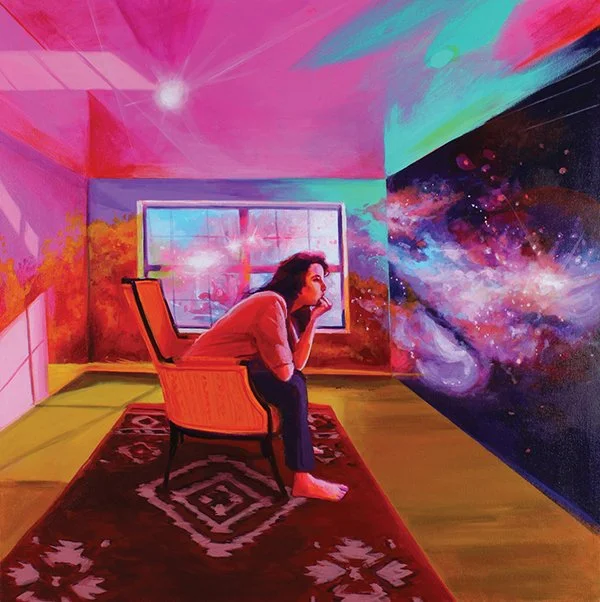

“Meanwhile, Galaxies Collide” (acrylic on canvas), by Medford, Mass.-based artist Bekka Teerlink, at the Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, Mass.

Her Web site says:

“Bekka Teerlink has no hometown; she moved frequently as a child which led her to escape into daydreams and build a sense of home in her mind to take wherever she went. She was always the outside observer which allowed her to see things fresh, and make connections in her mind between very different places, things, experiences that she collected along the way. In her work, she creates magical realist landscapes full of symbolism and suggestions of narrative and commentary on the world around her.’’