Virginia Raguin: Great art from flawed artists

Marko Rupnik

WORCESTER

Marko Rupnik, a Catholic priest, was expelled from the Jesuit order because he’d allegedly abused women. He was later accepted into the diocese in his native Slovenia. Rupnik is also an artist, and his work is on display in churches in Lourdes, Rome and Washington, D.C., among others.

Some of these sites are planning to cover or remove Rupnik’s art; some congregants and clergy disagree with such actions. The Vatican’s communication chief, Paolo Ruffini, for example, has defended the Holy See’s decision to keep Rupnik’s art on his department’s website.

As an art historian, I ask whether the debate is missing the point.

Bridging Eastern and Western European traditions

Rupnik’s art has been honored in the past as part of an effort by the Catholic Church to bridge Eastern and Western European faith traditions. With his heritage as a Slovenian, Rupnik was able to create imagery that blended both traditions. He was chosen in 1996 to decorate three of the four walls of the Redemptoris Mater Chapel of the Apostolic Palace in Vatican City with art that symbolized unity between the churches.

In 2016, Rupnik designed the logo for the Year of Mercy, a special spiritual jubilee declared by Pope Francis. Rupnik modeled Christ after the Eastern tradition of the “anastasis,” or resurrection, in which Christ is believed to have liberated the souls of the dead.

Rupnik was inspired by this 14th-Century fresco of the Anastasis at Instanbul’s Chora Church. Virginia Raguin, CC BY

Rupnik modeled his painting after a similarly themed 14th-century fresco at Istanbul’s Chora Church. He depicted Christ wearing a white robe, surrounded by an almond-shaped aureole of light. He placed Adam across Christ’s shoulders, a motif derived from early Christian images of Christ as the Good Shepherd.

His work echoed other historical precedents as well. Christ and Adam’s faces were pressed together and they shared a single eye to symbolize that Adam and Christ both shared a human nature. The motif of shared eyes to symbolize the single divine nature of the Christian Trinity appears in the art of the Renaissance.

Marko Rupnik, Anastasis. Collegio St. Stanislaus, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2006, realized by 'Atelier d’Arte e Architettura del Centro Aletti', Author provided (no reuse)

He was also commissioned to produce the mosaics that adorn St. John Paul II National Shrine in Washington, D.C.

Personal morality and creative production

Many revered works of art come from spiritually flawed creators. Raphael, whose frescoes, such as “The School of Athens,” adorn the room of the Segnatura in the Vatican, reportedly had many mistresses. Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio lived a short and violent life. He killed a man in a brawl, resulting in his receiving the death sentence for murder. Nonetheless, many of his paintings are seen as deep expressions of faith.

Caravaggio’s “Entombment of Christ,” one of the greatest treasures of the Vatican, depicts the sorrow of Christ’s followers. The artist’s “Madonna of Loreto,” located in the church of Sant'Agostino in Rome, has long been admired for its ability to bring the divine into everyday life. Thin, circular halos hover behind the heads of the Virgin and Child, who otherwise appear as ordinary people and resemble the two barefoot peasants kneeling before them. At the painting’s unveiling in 1606, some were distressed by the lack of dignity in depicting the Virgin and her divine child as commoners.

Madonna and Child. Caravaggio, Basilica of Saint Augustine in Campo Marzio courtesy Virginia Raguin, CC BY

During my visit to Sant'Agostino in 2009, I witnessed scores of people viewing the painting. Spectators invariably stood next to the peasant’s feet, demonstrating that they could somehow empathize with the pair’s devotion. For over an hour, I was reminded of the power of art regardless of where it came from.

Artists – and all humans – are inevitably flawed; once finished, I believe, an artist’s work is independent of its creator.

From my perspective, condemning art, rather than debating how the Catholic Church may have allowed someone accused of abuse to avoid censure for so long, is a diversion at best.

Virginia Raguin is a professor of humanities emerita, at the College of the Holy Cross, in Worcester.

Virginia Raguin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.

‘Between real and imaginary’

“Manana twilight”(acrylic on linen), by Dozier Bell, in her show “Genius loci,’’ at Sarah Bouchard Gallery, Woolwich, Maine, through Sept. 15.

The gallery says that Bell's work "embodies a reckoning with the unseen forces that shape and transform our lives," and her paintings "straddle the line between real and imaginary places while still evoking the powerful imagery of low-light scenes.''

In Woolwich around the turn of the last century.

Llewellyn King: What might happen if Google is broken up?

Google headquarters, in Mountain View, Calif.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Alphabet Inc.’s Google has few peers in the world of success. Founded on Sept. 4, 1998, it has a market capitalization of $1.98 trillion today.

It is global, envied, admired, and relied upon as the premier search engine. It is also hated. According to Google (yes, I googled it), it has 92 percent of the search business. Its name has entered English as a noun (google) and a verb (to google).

It has also swallowed so much of world’s advertising that it has been one of the chief instruments in the humbling and partial destruction of advertising-supported media, from local papers to the great names of publishing and television; all of which are suffering and many of which have failed, especially local radio and newspapers.

Google was the brainchild of two Stanford graduate students, Larry Page and Sergey Brin. In the course of its short history, it has changed the world.

When it arrived, it began to sweep away existing search engines quite simply because it was better, more flexible, amazingly easy to use, and it could produce an answer from a few words of inquiry.

There were seven major search engines fighting for market share back then: Yahoo, Alta Vista, Excite, Lycos, WebCrawler, Ask Jeeves and Netscape. A dozen others were in the market.

Since its initial success, Google, like Amazon, its giant tech compatriot, has grown beyond all imagination.

Google has continued its expansion by relentlessly buying other tech companies. According to its own search engine, Google has bought 256 smaller high-tech companies.

The question is: Is this a good thing? Is Google’s strategy to find talent and great, new businesses or to squelch potential rivals?

My guess is some of each. It has acquired a lot of talent through acquisition, but a lot of promising companies and their nascent products and services may never reach their potential under Google. They will be lost in the corporate weeds.

In the course of its acquisition binge, Google has changed the nature of tech startups. When Google itself launched, it was a time when startup companies made people rich when they went public, once they proved their mettle in the market.

Now, there is a new financing dynamic for tech startups: Venture capitalists ask if Google will buy the startup. The public doesn’t get a chance for a killing. Innovators have become farm teams for the biggies.

Europe has been seething about Google for a long time, and there are ongoing moves to break up Google there. Here, things were quiescent until the Department of Justice and a bipartisan group of attorneys general brought suit against the company for monopolizing the advertising market. If the U.S. efforts to bring Microsoft to heal is any guide, the case will drag on for years and finally die.

History doesn’t offer much guidance as to what would happen if Google were to be broken up; the best example and biggest since the Standard Oil breakup in 1911 is AT&T in 1992.

In both cases, the constituent parts grew faster than the parent. The AT&T breakup fostered the Baby Bells — some, like Verizon, have grown enormously. Standard Oil was the same: The parts were bigger than the sum had been.

When companies have merged with the government’s approval, the results have seldom been the corporate nirvana prophesied by those urging the merger, usually bankers and lawyers.

Case in point: the 1997 merger of McDonnell Douglas and Boeing. Overnight the nation went from having two large airframe manufacturers to having just one, Boeing. The price of that is now in the headlines as Boeing, without domestic competition, has fallen into the slothful ways of a monopoly.

Antitrust action against Google has few lessons to be learned from the past. Computer-related technology is just too dynamic; it moves too fast for the past to illustrate the future. That would have been true at any time in the past 20 years (the years of Google’s ascent), but it is more so now with the arrival of artificial intelligence.

If the Justice Department succeeds, and Google is broken up after many years of litigation and possible legislation, it may be unrecognizable as the Google of today.

It is reasonable to speculate that Google at the time of a breakup may be many times its current size. Artificial intelligence is expected to bring a new surge of growth to the big tech companies, which may change search engines altogether.

Am I assuming that the mighty ship Google is too big to sink? It hasn’t been a leader to date in AI and is reportedly playing catch up.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

UMaine setting up new aquaculture research and training center

Planned University of Maine aquaculture training and research center.

— Image courtesy of its architects, Andover, Mass.-based SMRT Architects and Engineers

Images from the book Maine Oysters: Stories of Resilience and Innovation

Edited from a New England Council report:

The University of Maine is working on a 14,200-square-foot addition to its Sustainable Workforce Innovation Center to serve the Pine Tree State’s growing aquaculture center.

Scheduled to open in 2025, at the university’s flagship campus, in Orono, the $10.3 million research and training center will prepare workers for aquaculture careers, and help the state address the challenges of its finfish, oyster and mussel farms.

“[The center] links research with teaching, so there’s classroom and research space together, and it brings in professionals from the aquaculture industry, academic researchers and experts and students to work together on identifying and addressing the kinds of issues that the aquaculture industry confronts,” said Trish Riley, chair of the University of Maine System Board of Trustees.

Bare-bones beauty

“Band of Light” (photo), by Massachusetts photographer Lisa Ryan, in the group show “Industrial Beauty-Luminous Desert,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, in Duxbury, Mass., opening Aug. 18.

David Warsh: We should pay more attention to this outfit

1050 Massachusetts Ave. in Cambridge, where the National Bureau of Economic Research is based.

— Photo by Astrophobe

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

An interesting fact: The leaders of Harvard University, Stanford University, Brown University and the University of California at Berkeley have something in common. Alan Garber, Jonathan Levin, Christina Paxson and Richard Lyons are all research associates of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Four out of 17,000+ NBER researchers, the preponderance of them economists, is not a large portion of the whole. But it may offer a hint of what top universities are looking for in their presidents.

The NBER is an unusual organization. Founded in 1920 by two individuals of very different outlooks, an executive of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company and a socialist labor organizer with a PhD from Columbia. Their idea was to fund independent studies of issues about which widespread differences of opinion existed: changes in the gap between rich and poor during the Gilded Age and the Progressive era, as well as the effects of large-scale immigration on wages. National income and its distribution have been the core of NBER studies ever since, along withe the structure of business cycles, too.

Since the 1970s, though, when its headquarters moved from New York City to Cambridge, Mass., and decentralized its research, a host of new topics have come under the NBER microscopes. Everything from the economics of health insurance and childhood education to inflation and national defense practices are investigated with imaginative theory, data, and statistical technique.

A look at the governance of the organization discloses the key to its success over a hundred years. Three classes of directors keep their eyes on the organization’s pursuits: a diverse collection of outsiders; a class of representatives of universities; and another of professional associations of one sort and another.

As in the days of its founding, the NBER seeks to bridge gaps between antagonistic factions. Its culture is suffused with respect for differences of opinion. Its goal is building consensus.

Would those characteristics be attractive to universities eager to get themselves off the front pages of newspapers?

Of course they would. A little more attention in those newspapers to NBER findings might help as well.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based Economic Principals.

The sound of nothing flapping

“Pintail Pair and Cattails’’ (wood), by Robert and Virginia Warfield, in the Jaffrey (N.H.) Historical Society’s show “The Warfield Collection,’’ at the Jaffrey Civic Center through Sept. 17. This exhibition consists of 50 exquisitely carved and painted birds produced between 1970 and 1990.

A cattail. They grow in New England marshes and kids love to whip them around.

Main Street in Jaffrey, in the Monadnock region, in 1907. The region has long had many artists and weekend and vacation homes.

The Mass. origins of the National Guard

With all the back-and-forth about Democratic vice presidential candidate Tim Walz’s National Guard Service, you might like to know that the origins of the U.S. National Guard can be traced back to December 1636, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony ordered the creation of three militia regiments to protect the new colony. Seen here is the first muster, in the spring of 1637, of the new force’s East Regiment, in Salem.

Thus the Bay Colony led the way in the creation of the militias eventually established by all American colonies. Some of the units ended up fighting in the Revolutionary War.

Note the Massachusetts Minute Man symbol.

‘Meditations on the lost and found.’’

“Walden Pond” (wood, plastic, foam, chiffon and bolts), by Mark Jarzombek (born 1954), in his show “Recollection,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Sept. 2. He’s an MIT-based architectural historian and artist.

He says:

“I inject playfulness and energy into construction materials I collect from from building sites. The pieces, meditations on the lost and the found, are inspired by Impressionist paintings, baroque perspectival effects and color pallets derived from Indian temples.”

Site of Henry David Thoreau's (1817-1862) cabin on Walden Pond, in Concord, Mass.

— Photo by Percival Kestreltail

Walden Pond.

— Photo by Erik Granlund

Chris Powell: When learning is optional

Scrapped mobile phones

— Photo by MikroLogika

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Schools increasingly are prohibiting students from operating or even carrying "smart phones" -- Internet-equipped telephones -- in class. Some schools are investing in special pouches in which students must lock their phones in school, being able to unlock them only with a special device made available when they are leaving.

At $25 or so each, the pouches are a significant expense, but educators find them effective at restoring students' concentration. The pouches even induce students to start talking to each other face to face.

Gov. Ned Lamont was an early advocate of banning "smart phones" in school, and while he was unable to get the General Assembly to legislate on the point, he has asked the state Education Department to draft and recommend such a policy to school superintendents and boards. It's a good idea and most school systems probably will go along with it if pressed by the Education Department.

But there is a bigger underlying problem here that no one in authority seems inclined to address.

For if students spend too much time on their "smart phones" in school, it's because they know they can afford to miss the teaching being attempted. They know they are going to be promoted from grade to grade and even graduated from high school no matter what. Learning is completely optional.

That is, even if school policy bans "smart phones," a bigger school policy will remain: social promotion. While it would be much more expensive, repealing social promotion would do much more to restore education than locking up "smart phones."

Repealing social promotion would require teachers and school administrators to enforce academic standards not just against students but also against their neglectful parents, who outnumber responsible parents in many school districts.

Like most states, Connecticut has resorted to social promotion to boost graduation rates and thereby make education look more successful even as it is failing, with the academic proficiency of students in basic subjects continuing to decline. Schools know that when uneducated students graduate they become someone else's problem -- the problem of employers and the welfare, medical, mental health, and criminal-justice systems.

The refusal to restore standards in public education may be behind the governor's recent conversion to "diversity, equity, and inclusion," the new euphemism for "affirmative action" -- racial and ethnic preferences in hiring, college admissions, and other endeavors.

Connecticut schools long have suffered an appalling gap between the educational achievement of white students and those from racial and ethnic minorities. The gap results mainly from something over which schools have no control -- the great disparity in the parenting and wealth of the homes students come from. Students who do poorly in school almost always need more attention at home, but state government declines to examine why they don't get it. More broadly, state government declines to inquire into why poverty endures and is worsening.

The state's primary policy for improving education is just to increase the compensation of educators. This has done little for education and nothing for closing the racial achievement gap, but it has kept Connecticut's biggest and most influential special interest, the teacher unions, working for the state's majority political party.

The governor's new plan to create an Office of Equity and Inclusion to diversify state government's workforce racially and in a few lesser respects indicates state government's acceptance of the racial achievement gap.

After all, if schools eliminated the gap and most high school graduates were of largely equal education across the races and ethnic groups, state government would not have to look so hard for qualified applicants from minority groups and would not have to incorporate racial and ethnic preferences into the hiring process in pursuit of diversity. Diversity and integration would occur naturally and income inequality would fall.

But the racial and ethnic gap in education generates an impoverished underclass dependent on government for sustenance, which in turn maintains government's power, size, and expense. In that respect the many who have made comfortable careers ministering to Connecticut's worsening poverty may consider the gap a great political success.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Llewellyn King: In which I score the first cat interview since J.D. Vance’s comments

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

After Republican vice-presidential nominee J.D. Vance denigrated women who keep cats and don’t have children, who he characterized as sad “cat ladies,” the media erupted. But none of my colleagues, to my knowledge, bothered with the No. 1 obligation of their trade: Get the other side of the story.

So, I thought it was my duty to go forth and interview at least one cat.

I can tell you that dogs are easy to interview. They will tell you anything you want to hear, and are prepared to perform for the camera.

Horses are a journalistic dream: They love to be on camera, especially live television, and will tell you the most extraordinary things. The rule is: If it comes from a horse’s mouth, verify.

But cats are a different story. They go for still photographs, preferably on social media. Facebook is a veritable showcase of posing felines.

But moving pictures? Not as much. Actually, interviewing cats and taking candid pictures takes fortitude. It isn’t easy to get a cat that will open up.

After several disdainful rejections (cats really know how to disdain) a Tuxedo house cat of the male persuasion, whose owner is a childless, middle-aged lady, agreed to be interviewed if I met certain conditions:

No moving pictures, just stills suitable for social media.

No petting or touching of any kind, unless initiated by the subject.

No attempts to bribe with food or “blandishments.”

The interview took place in a comfortable, suburban home with a cat named “Simba,” but who refused to answer to that name. He seemed to be a cat, as Rudyard Kipling wrote, who walked by himself.

The homeowner gave me permission to interview her cat in his environment: a sofa draped with a plush, anti-scratch slipcover.

ME to CAT: You don’t like the name Simba?

CAT: It is a family name, but only applies to lions in Africa. We are close but we don’t socialize, except on the Internet. If you go to Africa, I could arrange for you to be eaten. (A small, red tongue circled the rim of his mouth.)

ME: So you use the Internet?

CAT: Of course. Nearly all domestic cats have computer skills and can crack passwords.

ME: What is the deal with childless women?

CAT: We love them because children interrupt our lives at every level, from sleeping to surfing the net. Also, ladies are malleable.

Children manhandle you and have been known to throw cats out of windows, so they can find out how many lives we have.

ME: You are a house cat. How do you feel about that?

CAT: It is a lifestyle choice. I chose comfort over adventure. Would you turn the air-conditioning up two degrees?

Do you know we were worshipped in ancient Egypt and, indeed, we are divine. Silly to try to define how many lives we have: We are eternal.

ME: What do you think of people?

CAT: They have their uses, particularly if they leave their computers on, spend oodles of money on you at PetSmart, and provide companionship on demand. Our call, not theirs.

ME: What sites do you visit on the net when you are surfing?

CAT: “Hot Cats” is my favorite, very risqué.

ME: What do you think about J.D. Vance?

CAT: You are so slow. Why did it take you so long to ask the only question you want answered?

ME: I was seeking context.

CAT: I could scratch you. Would that be context enough?

ME: Well, what about the Republican vice-presidential pick?

CAT: If he sets foot in Africa, I will have one of my lion cousins, Simba or Leo, drive him up a tree and reason with him. He has caused me personal grief.

ME: How come?

CAT: My companion-lady -- cats don’t allow people to own them you know — was a loyal Republican and that was fine. Cats are more conservative. Dogs, I believe, are all Democrats.

She has become a Democrat and is thinking of adopting a child. If that happens, I shall have to consider new living arrangements.

Now, change my litter, take a picture of me sitting on the piano and post it to Facebook. I haven’t been on social media since the unpleasantness with JD Vance. Such a weird man. I may have to rig a voting machine or two.

ME: Can I ask ….

CAT: We are finished. Don’t forget to take the soiled litter on the way out.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

‘Sharp differentiation’

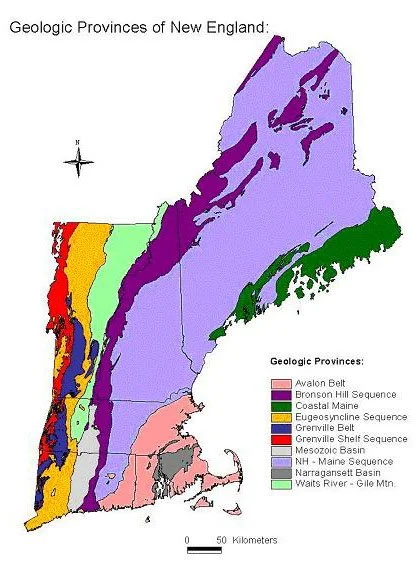

Map by G. R. Robinson Jr.

“In New England we have but to step across the border of the adjoining state to feel at once the sharp differentiation, the geological cut-off which expresses itself in the general aspect of the land and in the thousand and one simple facts of its topography, its flora, its fauna, its people, its customs, its coast, its climate, and its industries.’’

— Helen W. Henderson, in A Loiterer in New England (1919)

Pulp paradise in New Britain

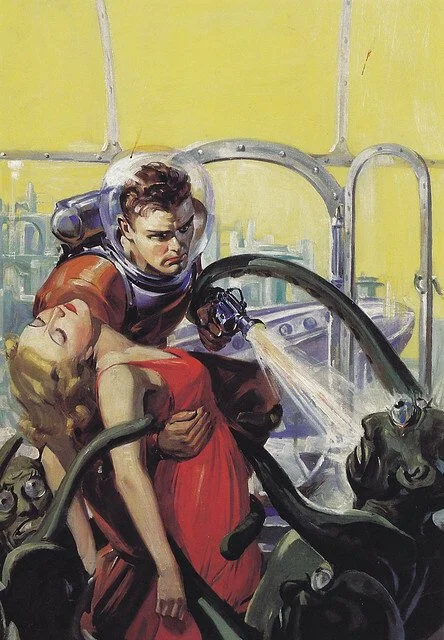

“Interplanetary Graveyard” (oil on canvas), by Howard Brown, from the March 1942 Future Fiction, in the show “WONDER STORIES: Pulp Art Illustration From the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art,’’ at that museum through Nov. 3.

The museum explains:

“The museum’s celebrated collection of Pulp Art illustration will be on view at the NBMAA and the Delamar Hotel in West Hartford, in a two-part exhibition highlighting the compelling narrative imagery depicted by artists of this genre.

“From the Great Depression through the World War II era, Americans turned to inexpensive novels referred to as ‘pulp-fiction’ as a form of entertainment and a way to escape their woes. These gripping stories, conceived before the age of television, were suffused with adventure and mystery. Often produced as series, pulp-fiction gave rise to iconic characters, such as The Shadow, The Phantom Detective, and Doc Savage, who many consider the forefathers of today’s comic book superheroes.’’

Ayse Coskun: AI strains data centers

Google Data Center, The Dalles, Ore.

— Photo by Visitor7

BOSTON

The artificial-intelligence boom has had such a profound effect on big tech companies that their energy consumption, and with it their carbon emissions, have surged.

The spectacular success of large language models such as ChatGPT has helped fuel this growth in energy demand. At 2.9 watt-hours per ChatGPT request, AI queries require about 10 times the electricity of traditional Google queries, according to the Electric Power Research Institute, a nonprofit research firm. Emerging AI capabilities such as audio and video generation are likely to add to this energy demand.

The energy needs of AI are shifting the calculus of energy companies. They’re now exploring previously untenable options, such as restarting a nuclear reactor at the Three Mile Island power plant, site of the infamous disaster in 1979, that has been dormant since 2019.

Data centers have had continuous growth for decades, but the magnitude of growth in the still-young era of large language models has been exceptional. AI requires a lot more computational and data storage resources than the pre-AI rate of data center growth could provide.

AI and the grid

Thanks to AI, the electrical grid – in many places already near its capacity or prone to stability challenges – is experiencing more pressure than before. There is also a substantial lag between computing growth and grid growth. Data centers take one to two years to build, while adding new power to the grid requires over four years.

As a recent report from the Electric Power Research Institute lays out, just 15 states contain 80% of the data centers in the U.S.. Some states – such as Virginia, home to Data Center Alley – astonishingly have over 25% of their electricity consumed by data centers. There are similar trends of clustered data center growth in other parts of the world. For example, Ireland has become a data center nation.

AI is having a big impact on the electrical grid and, potentially, the climate.

Along with the need to add more power generation to sustain this growth, nearly all countries have decarbonization goals. This means they are striving to integrate more renewable energy sources into the grid. Renewables such as wind and solar are intermittent: The wind doesn’t always blow and the sun doesn’t always shine. The dearth of cheap, green and scalable energy storage means the grid faces an even bigger problem matching supply with demand.

Additional challenges to data center growth include increasing use of water cooling for efficiency, which strains limited fresh water sources. As a result, some communities are pushing back against new data center investments.

Better tech

There are several ways the industry is addressing this energy crisis. First, computing hardware has gotten substantially more energy efficient over the years in terms of the operations executed per watt consumed. Data centers’ power use efficiency, a metric that shows the ratio of power consumed for computing versus for cooling and other infrastructure, has been reduced to 1.5 on average, and even to an impressive 1.2 in advanced facilities. New data centers have more efficient cooling by using water cooling and external cool air when it’s available.

Unfortunately, efficiency alone is not going to solve the sustainability problem. In fact, Jevons paradox points to how efficiency may result in an increase of energy consumption in the longer run. In addition, hardware efficiency gains have slowed down substantially, as the industry has hit the limits of chip technology scaling.

To continue improving efficiency, researchers are designing specialized hardware such as accelerators, new integration technologies such as 3D chips, and new chip cooling techniques.

Similarly, researchers are increasingly studying and developing data center cooling technologies. The Electric Power Research Institute report endorses new cooling methods, such as air-assisted liquid cooling and immersion cooling. While liquid cooling has already made its way into data centers, only a few new data centers have implemented the still-in-development immersion cooling.

Running computer servers in a liquid – rather than in air – could be a more efficient way to cool them. Craig Fritz, Sandia National Laboratories

Flexible future

A new way of building AI data centers is flexible computing, where the key idea is to compute more when electricity is cheaper, more available and greener, and less when it’s more expensive, scarce and polluting.

Data center operators can convert their facilities to be a flexible load on the grid. Academia and industry have provided early examples of data center demand response, where data centers regulate their power depending on power grid needs. For example, they can schedule certain computing tasks for off-peak hours.

Implementing broader and larger scale flexibility in power consumption requires innovation in hardware, software and grid-data center coordination. Especially for AI, there is much room to develop new strategies to tune data centers’ computational loads and therefore energy consumption. For example, data centers can scale back accuracy to reduce workloads when training AI models.

Realizing this vision requires better modeling and forecasting. Data centers can try to better understand and predict their loads and conditions. It’s also important to predict the grid load and growth.

The Electric Power Research Institute’s load forecasting initiative involves activities to help with grid planning and operations. Comprehensive monitoring and intelligent analytics – possibly relying on AI – for both data centers and the grid are essential for accurate forecasting.

On the edge

The U.S. is at a critical juncture with the explosive growth of AI. It is immensely difficult to integrate hundreds of megawatts of electricity demand into already strained grids. It might be time to rethink how the industry builds data centers.

One possibility is to sustainably build more edge data centers – smaller, widely distributed facilities – to bring computing to local communities. Edge data centers can also reliably add computing power to dense, urban regions without further stressing the grid. While these smaller centers currently make up 10% of data centers in the U.S., analysts project the market for smaller-scale edge data centers to grow by over 20% in the next five years.

Along with converting data centers into flexible and controllable loads, innovating in the edge data center space may make AI’s energy demands much more sustainable.

Ayse Coskun is a professor of electrical and computer engineering at .,Boston University

Disclosure statement

Ayse K. Coskun has recently received research funding from the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, IBM Research, Boston University Red Hat Collaboratory, and the Research Council of Norway. None of the recent funding is directly linked to this article.

Daniel Chang: Social media can help as well as hurt young people

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“You think at first, ‘That’s terrible. We need to get them off it. But when you find out why they’re doing it, it’s because it helps bring them a sense of identity affirmation when there’s something lacking in real life.”

— Linda Charmaraman, a research scientist and director of the Youth, Media & Wellbeing Research Lab at Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College, in Wellesley, Mass.

Social media’s effects on the mental health of young people are not well understood. That hasn’t stopped Congress, state legislatures, and the U.S. surgeon general from moving ahead with age bans and warning labels for YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram.

But the emphasis on fears about social media may cause policymakers to miss the mental health benefits it provides teenagers, say researchers, pediatricians, and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

In June, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, the nation’s top doctor, called for warning labels on social media platforms. The Senate approved the bipartisan Kids Online Safety Act and a companion bill, the Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act, on July 30. And at least 30 states have pending legislation relating to children and social media — from age bans and parental consent requirements to new digital and media literacy courses for K-12 students.

Most research suggests that some features of social media can be harmful: Algorithmically driven content can distort reality and spread misinformation; incessant notifications distract attention and disrupt sleep; and the anonymity that sites offer can embolden cyberbullies.

But social media can also be helpful for some young people, said Linda Charmaraman, a research scientist and director of the Youth, Media & Wellbeing Research Lab at Wellesley Centers for Women.

For children of color and LGBTQ+ young people — and others who may not see themselves represented broadly in society — social media can reduce isolation, according to Charmaraman’s research, which was published in the Handbook of Adolescent Digital Media Use and Mental Health. Age bans, she said, could disproportionately affect these marginalized groups, who also spend more time on the platforms.

“You think at first, ‘That’s terrible. We need to get them off it,’” she said. “But when you find out why they’re doing it, it’s because it helps bring them a sense of identity affirmation when there’s something lacking in real life.”

Arianne McCullough, 17, said she uses Instagram to connect with Black students like herself at Willamette University, where about 2% of students are Black.

“I know how isolating it can be feeling like you’re the only Black person, or any minority, in one space,” said McCullough, a freshman from Sacramento, California. “So, having someone I can text real quick and just say, ‘Let’s go hang out,’ is important.”

After about a month at Willamette, which is in Salem, Ore., McCullough assembled a social network with other Black students. “We’re all in a little group chat,” she said. “We talk and make plans.”

Social media hasn’t always been this useful for McCullough. After California schools closed during the pandemic, McCullough said, she stopped competing in soccer and track. She gained weight, she said, and her social- media feed was constantly promoting at-home workouts and fasting diets.

“That’s where the body comparisons came in,” McCullough said, noting that she felt more irritable, distracted, and sad. “I was comparing myself to other people and things that I wasn’t self-conscious of before.”

When her mother tried to take away the smartphone, McCullough responded with an emotional outburst. “It was definitely addictive,” said her mother, Rayvn McCullough, 38, of Sacramento.

Arianne said she eventually felt happier and more like herself once she cut back on her use of social media.

But the fear of missing out eventually crept back in, Arianne said. “I missed seeing what my friends were doing and having easy, fast communication with them.”

For a decade before the COVID-19 pandemic triggered what the American Academy of Pediatrics and other medical groups declared “a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health,” greater numbers of young people had been struggling with their mental health.

More young people were reporting feelings of hopelessness and sadness, as well as suicidal thoughts and behavior, according to behavioral surveys of students in grades nine through 12 conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The greater use of immersive social media — like the never-ending scroll of videos on YouTube, TikTok and Instagram — has been blamed for contributing to the crisis. But a committee of the national academies found that the relationship between social media and youth mental health is complex, with potential benefits as well as harms. Evidence of social media’s effect on child well-being remains limited, the committee reported this year, while calling on the National Institutes of Health and other research groups to prioritize funding such studies.

In its report, the committee cited legislation in Utah last year that places age and time limits on young people’s use of social media and warned that the policy could backfire.

“The legislators’ intent to protect time for sleep and schoolwork and to prevent at least some compulsive use could just as easily have unintended consequences, perhaps isolating young people from their support systems when they need them,” the report said.

Some states have considered policies that echo the national academies’ recommendations. For instance, Virginia and Maryland have adopted legislation that prohibits social media companies from selling or disclosing children’s personal data and requires platforms to default to privacy settings. Other states, including Colorado, Georgia, and West Virginia, have created curricula about the mental health effects of using social media for students in public schools, which the national academies also recommended.

The Kids Online Safety Act, which is now before the House of Representatives, would require parental consent for social media users younger than 13 and impose on companies a “duty of care” to protect users younger than 17 from harm, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal behavior. The second bill, the Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act, would ban platforms from targeting ads toward minors and collecting personal data on young people.

Attorneys general in California, Louisiana, Minnesota and dozens of other states have filed lawsuits in federal and state courts alleging that Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, misled the public about the dangers of social media for young people and ignored the potential damage to their mental health.

Most social-media companies require users to be at least 13, and the sites often include safety features, such as blocking adults from messaging minors and defaulting minors’ accounts to privacy settings.

Despite existing policies, the Department of Justice says some social-media companies don’t follow their own rules. On Aug. 2, it sued the parent company of TikTok for allegedly violating child privacy laws, saying the company knowingly let children younger than 13 on the platform, and collected data on their use.

Surveys show that age restrictions and parentalconsent requirements have popular support among adults.

NetChoice, an industry group whose members include Meta and Alphabet, which owns Google, and YouTube, has filed lawsuits against at least eight states, seeking to stop or overturn laws that impose age limits, verification requirements, and other policies aimed at protecting children.

Much of social media’s effect can depend on the content children consume and the features that keep them engaged with a platform, said Jenny Radesky, a physician and a co-director of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Center of Excellence on Social Media and Youth Mental Health.

Age bans, parental consent requirements, and other proposals may be well-meaning, she said, but they do not address what she considers to be “the real mechanism of harm”: business models that aim to keep young people posting, scrolling and purchasing.

“We’ve kind of created this system that’s not well designed to promote youth mental health,” Radesky said. “It’s designed to make lots of money for these platforms.”

Daniel Change is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter. Chaseedaw Giles, KFF Health News’ digital strategy & audience engagement editor, contributed to this report.

The way to go

At the Southern Vermont Arts Center’s (in Manchester) Exhibition by members of the Vermont Pastel Society through Sept. 22.

1913 photo

In response to global warming…

Baskets used in oyster farming

— Photo by Saoysters

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A couple of years ago, I edited a book about rapidly expanding oyster farming on the Maine Coast, and learned how some farmers are trying to adapt to the effects of global warming, which includes worsening storms amidst rising sea levels. Many are also addressing such environmental and public-health threats as microplastics by changing some of the equipment they use, such as switching from plastic to wooden cages.

Small entrepreneurs tend to respond quickly to changing circumstances, in this case out of enlightened self-interest.

xxx

Rather than just oppose wind turbines, such as off the southern New England coast, and solar farms, which is easy, foes would do well to say what they do support to address accelerating global warming from burning natural gas, oil and coal. Nuclear energy? Green hydrogen? Tidal power? Massive conversion of buildings to geothermal? Huge increase in the number of heat pumps? Suggestions needed.

The layered effect

“Excavation’’ (integrated medica collage), by Brewster, Mass.-based artist Mary Doering, in the 20-artist group show “What Lies Beneath,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Aug. 18.

The gallery says the exhibition explores what lies under layers.

An example of 17th Century vernacular architecture in Brewster, Dillingham House (c. 1660)

Keep it to yourself

Representation of "Humility" in a stained-glass window designed by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), English artist and designer.

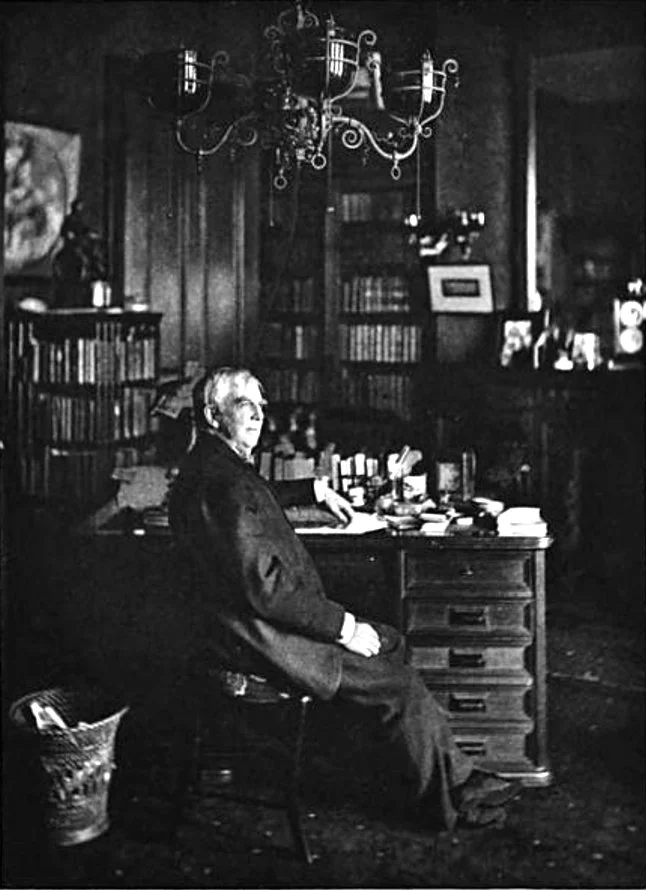

“Humility is the first of virtues — for other people.’’

— Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1809-1894), Boston-based physician and poet

Holmes in his study

Libby Handros: My times with Lewis Lapham, great editor and essayist and sparkling colleague

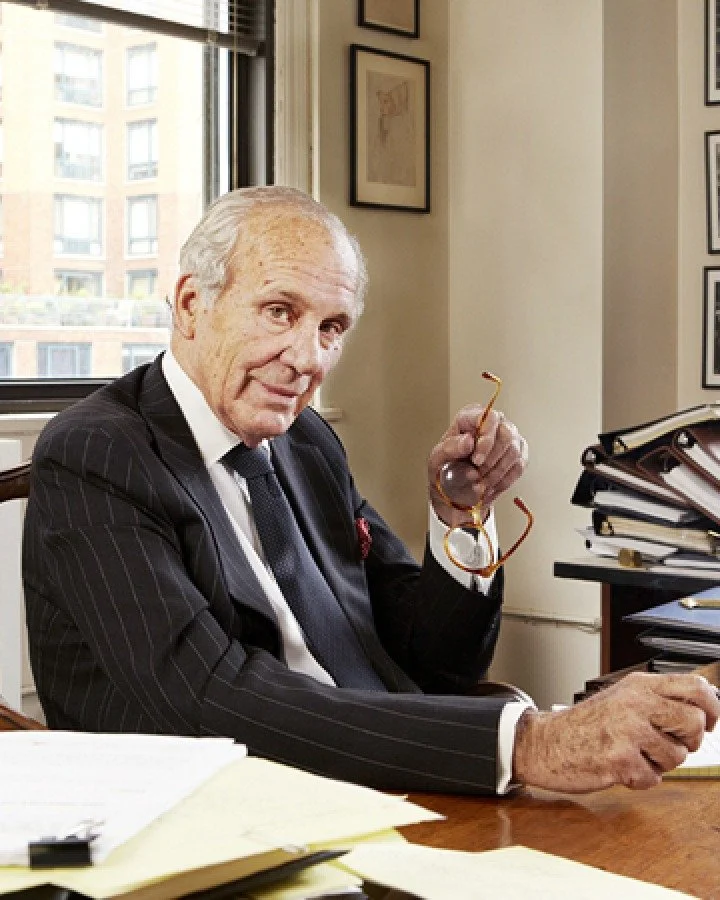

Lewis H. Lapham

— Photo by Joshua Simpson

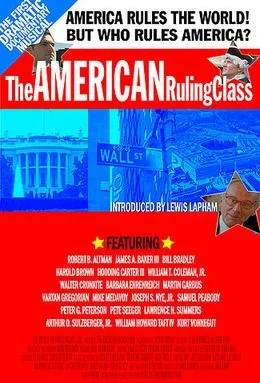

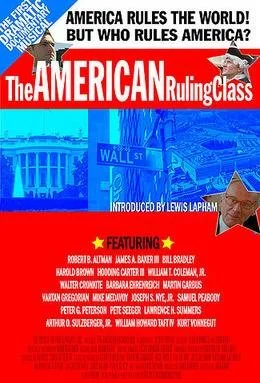

Lewis H. Lapham wrote and hosted this droll musical film.

I first met Lewis Lapham in the late 80’s at a glittering cocktail party honoring a well-known television critic. It was the type of party that is no longer thrown, and it was also the type of party that Lewis, in his inimitable way, would have had fun critiquing. My boss, Ned Schnurman, introduced us. Ned had great respect for Lewis, who had helped rescue Harper’s Magazine just a few years before. Lewis died on July 23 at 89.

After the cocktail party I ran into Lewis again, having a nightcap at the Hotel Pierre. There, we discussed his idea to do a show that framed the events of the day from the perspective of the past. The two of us collaborated on a proposal for it, but the timing was off, so that particular series was never made.

Sometime later, I was producing a documentary on the “crime of the century” — the Lindbergh-baby kidnapping — and how coverage of the kidnapping and its subsequent trial were the precursors of tabloid television journalism. I needed someone to write the script, and asked Lewis. He had just the right sensibility to connect the contemporary spectacle of the O.J. Simpson trial to the Lindbergh-baby events that had taken place all those years ago in New Jersey. He wrote a beautiful script.

Now we needed an editor. A friend said she knew someone: John Kirby. John had just lost his job, so he was available. The two of us met, little suspecting that a decades-long business partnership would result. I do not recall saying too much. I simply handed John a copy of Lewis’s recently published Lapham’s Rules of Influence. John laughed his way through the book at lunch, and a couple of hours later he was back in my office, full of enthusiasm. “If I had read this book sooner, I might not have just been fired,” he told me.

John’s rough-cut — which made the script into a film — was soon ready for Lewis to review, and the two of them met. They hit it off immediately. Later, after a screening of another cut, Lewis looked at John and said, “Kirby, next time we are going to pick the pictures together.” A year or so after that, the three of us collaborated again, this time on The American Ruling Class, a cutting-edge “dramatic documentary musical” film that follows two newly minted college graduates through the halls of mammon and power.

Lewis found the demands of filmmaking annoyingly time-consuming, but he was always good-natured about it. During the making of ARC, he did take after take outside the Council on Foreign Relations. He sat in the New York Times boardroom talking to Pinch Sulzberger in his own seemingly innocuous way that was anything but. He patiently put up with repeated takes at Elaine’s, the once celebrated Manhattan restaurant and watering hole, sitting with Nickel and Dimed author Barbara Ehrenreich as in a diner. (She was recreating her undercover role as a waitress in the lead-up to a song based on her book.)

There was one shoot that Lewis actually enjoyed: the day we filmed a scene on a golf course. He was happy to keep practicing his swing while we reset the shot or worked with another actor. Eventually I noticed that people were watching him, entranced. One of the onlookers came up to me. “Who is that man practicing his swing?” he asked, pointing. “Lewis Lapham, the editor of Harper’s Magazine,” I responded. The guy’s incredulous reply surprised me: “You mean he isn’t a famous pro?!”

It turned out that, unbeknownst to us, Lewis was a phenomenal golfer. At the Blind Brook Club, the great and near-great of corporate America asked Lewis to join their foursome. After a round of golf, they would settle in for a game of bridge — something else Lewis excelled at.

Years later, Lewis wrote about his personal connection to golf and bridge for Lapham’s Quarterly:

Both my father and my grandfather taught the lesson on the golf course and at the card table. Golf they construed as a trying of the spirit and a searching of the soul. Scornful of what they called “the card-and-pencil point of view,” they looked askance at adding up the mundane trifle of a paltry score.

How one plays the game was more to the point than whether the game is won or lost. Play the shot and accept the consequences, play the shot and know thyself for a bragging scoundrel or a Christian gentleman. So fundamental was my grandfather’s disdain for mere numbers that, at the bridge table, he deemed it ungentlemanly to look at his cards before announcing a bid.

Made for the BBC, The American Ruling Class had a successful festival and theatrical run. It was the most-watched film at the Tribeca Film Festival that year and received special mention in the “New York Loves Documentary” feature category. Lewis, John and I were subsequently invited to attend the prestigious International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam. Of course we went. Lewis was bemused by his three days there, and John and I were lucky to be with him as he soaked it all in — then wrote about it for Harper’s as only Lewis could, in a piece entitled “Eyes Wide Shut.”

… I was given the chance to look at sequences from a large number of films that one or another of the festival judges thought notable for their cinematography, story lines, and tones of voice — investigative, satirical, didactic, metaphorical, polemical, elegiac. What was striking was the broad range of topic and narrative possibility undreamed of in the philosophy of our own broadcast and cable networks — the civil war in the Sudan (unedited by the missionaries at CNN); cockroach races in Moscow; a pregnant Ukrainian wife sold into the white slave trade and shipped south to Turkey; Honduran peasants hopping Mexican freight trains on their journeys north to the Texas border; street riots in Caracas, happiness in Odessa; Chinese children paid six cents an hour to pick threads from blue jeans on the way to Rodeo Drive; the death in Baghdad of an Iraqi shopkeeper; Brazilian soybeans, genetically modified, being fed to Austrian-engineered chickens. Various in perspective and duration (nine and ninety minutes, with or without voice-over, messages both programmed and spontaneous), the films gave a face, name, age, and address to the grand but often meaningless abstractions that decorate presidential press conferences and drift across the surface of television news — “globalization,” “multinational corporation,” “political unrest,” “environmental degradation,” “widespread poverty,” “incurable disease.”

It is perhaps the best piece ever written about a film festival.

On our last night in Amsterdam, our BBC commissioning editor, Nick Fraser, rounded up a large group of us for dinner. On the way to the restaurant, Lewis announced that he wanted to see “the girls in the window” — aka the city’s infamous red-light district. Then as now, prostitution was legal in Amsterdam, and the girls showed their wares by sitting in picture windows. It was sad. We saw … and left.

After dinner, Lewis wanted to partake in another Dutch tradition: the “coffeeshop,” where pot and hash were also legal. It had been a while since Lewis had smoked pot, he said, but that night he did. What he really enjoyed, however, was his trip to the Rijksmuseum to see the Van Goghs. He loved how the painter captured all walks of society.

In all this time, Lewis had never given up on the original idea that he had pitched to me the first night we’d met: to frame current events from an historical perspective. By now, though, the idea had evolved. He was envisioning a quarterly publication that would focus on a single subject of “current interest and concern — war, poverty, religion, money, medicine, nature, crime — by bringing up to the microphone of the present the advice and counsel of the past.” Thus, Lapham’s Quarterly was born. At an age when others would have been happy to retire and play golf and bridge, Lewis launched a new publication.

The fledgling magazine needed a home, so for several months, Lewis and his small team worked out of our studio in DUMBO, Brooklyn. Lewis sat in our glass box of an editing room with a yellow legal pad, writing and bringing his longtime dream to life. As the circulation for Lapham’s Quarterly grew, Lewis could not have been prouder. He delighted in telling people that, thanks to a grant, his magazine was available in prison libraries.

Much has already been written about how Lewis helped save Harper’s, and the innovations he brought to that magazine. But there was precedent. Some 60 years earlier, another magazine editor had similarly shaken the publishing world: Scofield Thayer, who had taken the reins of The Dial magazine launched by Ralph Waldo Emerson in the 1840s and turned it into the most influential literary publication in 1920s America. Many of the major writers and artists of the day were among the revitalized title’s contributors, such as Sinclair Lewis, Amy Lowell, Archibald MacLeish, Bertrand Russell, Wallace Stevens; Chagall, Matisse, O’Keeffe and Picasso.

Lewis knew his publishing history. The first time he held a copy of The Dial in his hands, he was amazed by its design elements, starting with the table of contents. He realized that he had unconsciously borrowed from Thayer. A mutual friend recognized Thayer’s importance in the world of art and magazine publishing and suggested we make a documentary. We connected everyone, and set out with Lewis as our guide to make a film about Thayer and The Dial; we hope to complete it in the near future, as a memorial to two beloved and innovative editors.

I have not read every single one of Lewis’s Harper’s columns, but I have read many — including his first, which was written in the oil fields of Alaska. Choosing a favorite piece of prose by Lewis Lapham isn’t easy. Everything he wrote offered a new insight, a unique way of viewing the subject du jour. My personal all-time favorite is the prescient, fantastical “A Pig for All Seasons,” which was written during the heyday of the Reagan era and published in the June 1986 Harper’s. As described by Lapham’s Quarterly’s editors, the column “details the rise of the humble pig to the upper echelons of New York society, where it will serve as both companion and bodily insurance policy.”

You can listen to Lewis read the piece on the Quarterly’s site. I must, however, share some of my favorite excerpts here. I think it is Lewis at his inimitable best.

Certainly the manufacture of handmade pigs was consistent with the spirit of an age devoted to the beauty of money. For the kind of people who already own most everything worth owning — for President Reagan’s friends in Beverly Hills and the newly minted plutocracy that glitters in the show windows of the national media — what toy or bauble could match the priceless objet d’art of a surrogate self?

And:

The possession of such a pig obviously would become a status symbol of the first rank, and I expect that the animals sold to the carriage trade would cost at least as much as a Rolls-Royce or beachfront property in Malibu. Anybody wishing to present an affluent countenance to the world would be obliged to buy a pig for every member of the household — for the servants and secretaries as well as for the children. Some people would keep a pig at both their town and country residences, and celebrities as precious as Joan Collins or as nervous as General Alexander Haig might keep herds of twenty to thirty pigs.

Lewis could not stop imagining the pig as a sign of social status and security blanket rolled into one:

As pigs became more familiar as companions to the rich and famous, they might begin to attend charity balls and theater benefits. I can envision collections of well-known people posing with their pigs for photographs in the fashion magazines — Katharine Graham and her pig at Nantucket, William Casey and his pig at Palm Beach, Norman Mailer and his pig pondering a metaphor in the writer’s study.

Celebrities too busy to attend all the occasions to which they’re invited might choose to send their pigs. The substitution could not be construed as an insult, because the pigs — being extraordinarily expensive and well dressed — could be seen as ornamental figures of a stature (and sometimes subtlety of mind) equivalent to that of their patrons. Senators could send their pigs to routine committee meetings, and President Reagan might send one or more of his pigs to state funerals in lieu of Vice President Bush.

People constantly worrying about medical emergencies probably wouldn’t want to leave home without their pigs. Individuals suffering only mild degrees of stress might get in the habit of leading their pigs around on leashes, as if they were poodles or Yorkshire terriers. People displaying advanced symptoms of anxiety might choose to sit for hours on a sofa or a park bench, clutching their pigs as if they were the best of all possible teddy bears, content to look upon the world with the beatific smile of people who know they have been saved.

Lewis was always open to new ideas, which made having drinks with him something to really look forward to. He would frequently arrive pulling a random book or magazine or essay draft out of his Lapham’s Quarterly tote and excitedly talking about it. His personal stories were wonderful, too, whether he was talking about the time he spent as crew on a freighter, or the time he traveled with John D. Rockefeller III to help him promote the idea of birth control, or the time his godfather negotiated with Goering for the return of the Texaco tankers at the start of World War II. A great reporter at heart, Lewis knew a good story when he saw one. Even better, he knew how to tell it.

Lewis was a pleasure to work with. A good friend. An irreplaceable loss.

The tribute to him in Lapham’s Quarterly does him proud. I recommend that you read it.

—Libby Handros, producer, The Press & the Public Project