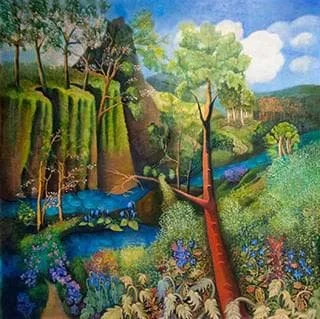

‘Reality and imagination’

From Wendy Clough’s show “Landscape in Transformation,’’ at the Davidow Fine Art Gallery at Colby Sawyer College, New London, Conn., Sept. 26-Dec. 3.

She says:

“The theme of my work is animated nature and my experience of the natural world. Having spent the majority of my life in New Hampshire and Colorado, I have been and am surrounded by natural beauty. I use my painting and my fiber art to explore ideas such as memory, nostalgia, the value of nature, and the link between reality and imagination.’’

Lake Sunapee, a famed summer attraction in the New London area.

What they like

— Photo by David Shankbone

Excerpted and edited from a Boston Guardian article

Thanks to miles of very old sewage infrastructure, population density, improperly disposed food refuse and an emphasis on poisoning over prevention, Downtown Boston is home to more rats than anywhere else in the city….

The number one driver of rat populations is food refuse, and open-air markets, abundant restaurants and aging infrastructure make downtown the perfect environment for rodent populations to thrive. A single reliable food source, such as food shrapnel from litter or markets, improperly used dumpsters, plastic garbage bags and cheap trash cans, can sustain hundreds of rats that will spill over into adjacent areas.

The Norway rat, Boston’s only rat species, is capable of chewing through the most commonly used cheap plastic trash can in under an hour. Food refuse left out in plastic bags doesn’t stand a chance.

Boston Rodent Action Plan recommendations reflect an emphasis on prevention, rather than the typically reactive responses of property owners.

“Rat poison bait boxes were found to be overly abundant in locations and in numbers per location, to the point of nonsensical and in some areas also not in adherence EPA pesticide label laws, in virtually all the neighborhoods visited,” reports the BRAP. Boston’s miles of old brick sewers are a sprawling home to centuries-old rat colonies that will happily replace exterminated surface rats so long as food refuse remains accessible.

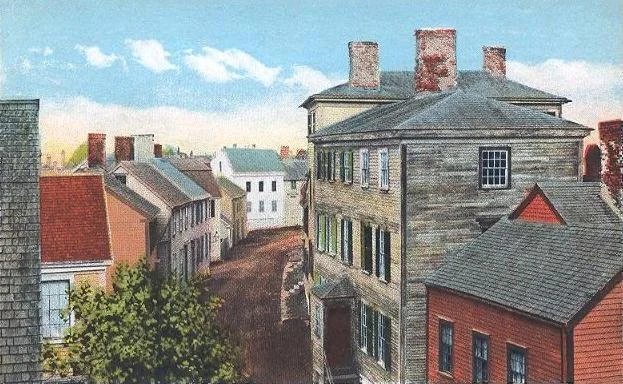

Downtown Boston

— Photo by Nick Allen

Wash before eating

“Endowment” (archival digital print), in Newton, Mass.-based photographer Francine Zaslow’s show “Elements,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Sept. 1.

She says:

“As a still-life photographer, my tabletop becomes a stage for a wide but diverse collection of props.

Transposing elements with light and an unbridled honesty, I want to show every detail, both raw and unveiled.

My images explore a wide range of texture and forms, often employing unique found objects that transport the viewer to other worlds, unknown places in time, echoing a story told, a memory saved.’’

Chris Powell: Bears become less cute in Conn.

A black bear (the kind that live in New England)

— Photo by Diginatur ]

MANCHESTER, Conn.

As their appearances in Connecticut become more frequent and damaging, bears become less cute and amusing.

According to the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, in the last two weeks:

-- A woman sitting in her back yard in Cheshire was attacked by a bear that snuck up on her from behind. She suffered two puncture wounds before managing to scare it away.

-- A man driving a small car on the Route 8 expressway in Torrington struck a bear that ran in front of him, causing the car to crash into a guard rail. The driver was uninjured but the bear was killed and turned out to weigh more than 500 pounds, almost as much as the car.

-- A bear and its cub broke into a car in Winsted, destroying the interior.

-- And residents of a home in Winchester interrupted a bear's attempt to break in.

An official of the environmental agency says Connecticut is "good habitat" for bears and "they are here to stay."

Why is that?

It's because while state law now permits killing bears in self-defense or in defense of pets, in other encounters people are just supposed to shoo bears onto a neighbor's property. Bears have no natural predator except man, and state government long has prohibited hunting them. Indeed, Connecticut is the only New England state without a bear-hunting season.

If bears really are "here to stay," they won't be stopped by securing trash cans and barbecue grills and taking down birdfeeders, as the environmental agency and bear lovers urge. There were no trash cans, barbecue grills, and birdfeeders in the forests through which the bears migrated back into Connecticut. Without predators, their population increased naturally and the northern forests couldn't support all of them.

So now bears will be reproducing in Connecticut until every town has many of them, and the more the state is "good habitat" for bears, the less it will be "good habitat" for people. Only a long hunting season will stop bears, and that won't happen until state legislators are more scared of bears and the harm they increasingly do than they are scared of the bear lovers and apologists.

xxx

Connecticut Inside Investigator, a product of the Yankee Institute, reported the other day that state government has bigger management deficiencies than the supposed lack of diversity that has become Gov. Ned Lamont's new focus.

The news organization said Central Connecticut State University has paid nearly $763,000 to Christopher Dukes, its former director of student conduct, who, the state Supreme Court recently ruled, was wrongly fired in 2018 after police responded to a complaint that he had assaulted his wife at their home. Police arrested him there after a standoff.

The university seems to have decided that since the director of student conduct handles complaints of abuse and harassment, it wouldn't be right to have a director who was in that kind of trouble himself. But the man denied the charges, they were dropped eventually, and the incident involved conduct off the job, not on the job.

His dismissal went to arbitration, which ordered him rehired. The university appealed to Superior Court, where the arbitration award was vacated and the dismissal upheld. But then the man appealed to the state Supreme Court, which overturned the Superior Court and reinstated the arbitration award with its huge liability in back pay.

Was the university right or wrong to persist with the dismissal though its cause did not involve the employee's job performance and the criminal charges were dropped? There is an argument on both sides, but a risk to due process should have been clear to the university. It might have been better just to transfer him to a position not involving complaints of abuse and harassment.

In any case state government looks ridiculous here, and if the General Assembly ever comes to think that $763,000 is a lot of money to waste, it should investigate what happened, ascertain what legal advice the university got, and set clear policy so this kind of thing can't happen again.

xxx

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Llewellyn King: The wild and fabulous medical frontier with predictive AI

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When is a workplace at its happiest? I would submit that it is during the early stages of a project that is succeeding, whether it is a restaurant, an Internet startup or a laboratory that is making phenomenal progress in its field of inquiry.

There is a sustained ebullience in a lab when the researchers know that they are pushing back the frontiers of science, opening vistas of human possibility and reaping the extraordinary rewards that accompany just learning something big. There has been a special euphoria in science ever since Archimedes jumped out of his bath in ancient Greece, supposedly shouting, “Eureka!”

I had a sense of this excitement when interviewing two exceptional scientists, Marina Sirota and Alice Tang, at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), for the independent PBS television program White House Chronicle.

Sirota and Tang have published a seminal paper on the early detection of Alzheimer’s Disease — as much as 10 years before onset — with machine learning and artificial intelligence. The researchers were hugely excited by their findings and what their line of research will do for the early detection and avoidance of complex diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and many more.

It excited me — as someone who has been worried about the impact of AI on everything, from the integrity of elections to the loss of jobs — because the research at UCSF offers a clear example of the strides in medicine that are unfolding through computational science. “This time it’s different,” said Omar Hatamleh, who heads up AI for NASA at the Goddard Space Flight Center, in Greenbelt, Md.

In laboratories such as the one in San Francisco, human expectations are being revolutionized.

Sirota said, “At my lab …. the idea is to use both molecular data and clinical data [which is what you generate when you visit your doctor] and apply machine learning and artificial intelligence.”

Tang, who has just finished her PhD and is studying to be a medical doctor, explained, “It is the combination of diseases that allows our model to predict onset.”

In their study, Sirota and Tang found that osteoporosis is predictive of Alzheimer’s in women, highlighting the interplay between bone health and dementia risk.

The UCSF researchers used this approach to find predictive patterns from 5 million clinical patient records held by the university in its database. From these, there emerged a relationship between osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s, especially in women. This is important as two-thirds of Alzheimer’s sufferers are women.

The researchers cautioned that it isn’t axiomatic that osteoporosis leads to Alzheimer’s, but it is true in about 70 percent of cases. Also, they said they are critically aware of historical bias in available data — for example, that most of it is from white people in a particular social-economic class.

There are, Sirota and Tang said, contributory factors they found in Alzheimer’s. These include hypertension, vitamin D deficiency and heightened cholesterol. In men, erectile dysfunction and enlarged prostate are also predictive. These findings were published in “Nature Aging” early this year.

Predictive analysis has potential applications for many diseases. It will be possible to detect them well in advance of onset and, therefore, to develop therapies.

This kind of predictive analysis has been used to anticipate homelessness so that intervention – like rent assistance — can be applied before a family is thrown out on the street. Institutional charity is normally slow and often identifies at-risk people after a catastrophe has occurred.

AI is beginning to influence many aspects of the way we live, from telephoning a banker to utilities’ efforts to spot and control at-risk vegetation before a spark ignites a wildfire.

While the challenges of AI, from its wrongful use by authoritarian rulers and its menace in war and social control, are real, the uses just in medicine are awesome. In medicine, it is the beginning of a new time in human health, as the frontiers of disease are understood and pushed back as never before. Eureka! Eureka! Eureka!

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Dr. Yukie Nagai's predictive learning architecture for predicting sensorimotor signals.

— Dr. Yukie Nagai - https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2018.0030

Don’t make yourself at home

“Rising/Sinking studies (chair)” (wood and milk paint), by Portland, Maine-based Ling-Wen Tsai, at Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine, in the group show “Life Forms Preview’’.

The gallery explains:

“Corey Daniels Gallery is pleased to present ‘Life Forms Preview’ in collaboration with the 12 artist sculpture collective made up of Jackie Brown, Lynn Duryea, Leah Gauthier, Kazumi Hoshino, Elaine K. Ng, Bronwen O’Wril, Ashley Page, Veronica Perez, Celeste Roberge, Naomi David Russo, Ling-Wen Tsai and Erin Woodbrey.

“We’re thrilled to be the first venue to show work by all 12 artists, giving the public a precursor to their upcoming four-year exhibition program throughout the State of Maine. Each artist is pushing the boundaries of contemporary sculpture and the work will be organically integrated throughout the gallery.’’

Wells Beach, with summer and full-time houses along it, in September 2017. The beach has suffered much erosion in storms since then.

Photo by Fred Hsu

What we have

The house of the late poet and essayist Donald Hall (1928-2018) and his wife, poet Jane Kenyon (1947-1995), at Eagle Pond Farm, in Wilmot, N.H.

“New York has people, the Northwest rain, Iowa soybeans, and Texas money. New Hampshire has weather and seasons.’’

—Donald Hall in Here at Eagle Pond.

Circa 1910 postcard

William Morgan: Matrimony in Mattapoisett

Photos and text by William Morgan, a Providence-based architectural historian and critic and a photographer.

John Quincy Adams, the only president to return to Congress after his term in the Oval Office, was instrumental in establishing the Ned’s Point Lighthouse, in Mattapoisett, Mass., in 1838. Automated in 1923, the beacon is now the center of a park in the boating community on Buzzards Bay–a perfect summer place to throw frisbee or fly a kite. The lighthouse is also the focus of formal wedding pictures.

After hot dogs and ice cream in Mattapoisett, my wife, Carolyn, and I often go to Ned’s Point to look over the harbor and across the bay to the western shore of Cape Cod and south to the Elizabeth Islands. On a recent Saturday, our reverie was broken by the arrival of a black van that disgorged three photographers, dressed in black and looking like a SWAT team, their many cameras hanging in holsters; one of the crew launched a drone camera. Then a black bus, with blacked-out windows–the kind that rock stars and country music singers travel in–emptied out a bride and groom and their 14 attendants. The uber-professional documenters herded their flock into various tableaux.

One can only imagine what this one element of a larger matrimonial production cost. Weddings have gotten bigger, fancier and more expensive. Strapless gowns with billowing skirts (to hide America’s ever-increasing avoirdupois?), along with ubiquitous disfiguring tattoos. As is typical of most weddings of the last decade, the men wear too-tight suits with short tails and medium brown shoes.

A week later, a similar photo-assault scenario was repeated. But this time, it was just the bride and groom. It was also a Friday, so perhaps it was a preview photo shoot (the flowers were provided by the picture takers) or a much smaller wedding. (Carolyn and I have a theory that the larger the wedding, the less likely the marriage is to survive. We were married at a courthouse 45 years ago.) Whatever the circumstances, the wedding pair were almost refreshingly old-fashioned: he with black shoes and a dinner jacket; she in a simple, although somewhat risqué, diaphanous sheath.

Unglue from New England 'emasculate scholarship'

The Boston Latin School, founded in 1635 as the first public school in America.

“If any pale student, glued to his desk, here seek an apology for a way of life whose natural fruits is that pallid and emasculate scholarship of which New England has too many examples, it will be far better that this sketch had not been written. For the student there is, in its season, no better place than the saddle, and no better companion than the rifle or the oar.’’

— Francis Parkman Jr. (1823-1893), Boston-based historian, including of the American West.

It’s watching you

Detail From Esther Ruiz’s show “Uncharted’,’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Greenwich, Conn., through Sept. 2.

The museum says:

“Uncharted’’ is Esther Ruiz’s first solo museum presentation on the East Coast, and the eighth installment of “Aldrich Projects,’’ a quarterly series featuring one work or a focused body of work by a single artist on the Museum’s campus. Debuting new sculptures from Ruiz’s “Beacon’’ series alongside “Codex” (2023), these enigmatic objects consider the relationships between the natural and the artificial, the familiar and the alien, and the temporal and transcendental.’’

Offshore wind turbines connected by underwater grid could revolutionize East Coast electricity sector

HANOVER, N.H.

Offshore winds have the potential to supply coastlines with massive, consistent flows of clean electricity. One study estimates wind farms just offshore could meet 11 times the projected global electricity demand in 2040.

In the U.S., the East Coast is an ideal location to capture this power, but there’s a problem: getting electricity from ocean wind farms to the cities and towns that need it.

While everyone wants reliable electricity in their homes and businesses, few support the construction of the transmission lines necessary to get it there. This has always been a problem, both in the U.S. and internationally, but it is becoming an even bigger challenge as countries speed toward net-zero carbon energy systems that will use more electricity.

The U.S. Department of Energy and 10 states in the Northeast States Collaborative on Interregional Transmission are working on a potentially transformative solution: plans for an offshore electric power grid.

How an offshore transmission backbone could reduce the number of transmission lines and land crossings. Illustrations by Billy Roberts, NREL

At the core of this grid would be backbone transmission lines off the East Coast, from North Carolina to Maine, where dozens of offshore wind projects are already in the pipeline.

The plans envision it supporting at least 85 gigawatts of offshore wind power by 2050 – close to the U.S. goal of 110 GW of installed wind power by mid-century, enough to power 40 million homes and up from 0.2 GW today. The Department of Energy and the Northeast States Collaborative formalized their goals in July 2024 through a multistate memorandum of understanding.

Emerging research from the Department of Energy, the research company Brattle and other groups suggests that an offshore electric power grid could mitigate key challenges to building new transmission lines on land and reduce the costs of offshore wind power.

Cutting costs would be welcome news – offshore wind project costs rose as much as 50% from 2021 to 2023. While some of the underlying causes have subsided, such as inflation and global supply chain disruptions, interest rates remain high, and the industry is still trying to find its footing in the U.S.

What is an offshore electric power grid?

Today’s offshore wind projects use a point-to-point, or radial design, where each offshore wind farm is individually connected to the onshore grid.

This method works if a region has only a few projects, but it quickly becomes more expensive due to the cabling and other infrastructure. Its lines are also disruptive to communities and marine life. And it requires more costly onshore grid upgrades.

Coordinated offshore transmission can avoid many of those costs with what the Department of Energy calls “meshed” or “backbone” designs.

Rather than individual connections to land, many offshore wind farms would be connected to a shared transmission line, which would connect to the onshore grid through strategically placed “points of interconnection.” This way, electricity produced by an offshore wind farm would be transmitted to where it is most needed, up and down the East Coast.

Several areas along the Atlantic continental shelf have been leased for wind power development. U.S. Department of the Interior, 2024

Even better, electricity generated onshore could also be transmitted through these shared lines to move energy to where it is needed. This could improve the resilience of power grids and reduce the need for new transmission lines over land, which have been notoriously difficult to gain approval for, especially on the East Coast.

Coordinated offshore transmission was part of early U.S. discussions on offshore wind planning and development. In the late 2000s when Google and partners first proposed the Atlantic Wind Connection, an offshore transmission project, the benefits in both offshore renewables and the entire energy system were intriguing. At the time, the U.S. had just one utility-scale offshore wind project in the pipeline, and it ultimately failed.

Today, the U.S. has 53 GW of offshore wind projects being planned or developed. As energy researchers, we believe coordinated offshore transmission is important for the industry to succeed at scale.

Offshore grid could save money, reduce impacts

By enabling power from offshore wind farms and onshore electricity generators to travel to more places, coordinated transmission can enhance grid reliability and enable electricity to get to where it is most needed. This reduces the need for more expensive and often more polluting power plants.

A 2024 report from the National Renewable Energy Lab found the benefits of a coordinated design are nearly three times higher than the costs when compared with a standard point-to-point design.

Studies from Europe, the U.K. and Brattle have pointed to additional benefits, including reducing planet-warming carbon emissions, cutting the number of beach crossings by a third and reducing the miles of transmission cables needed by 35% to 60%.

Three transmission designs show the difference between intraregional systems with several land connections and interregional and backbone designs. These three were investigated by the National Renewable Energy Lab in the Atlantic Offshore Wind Transmission Study. Illustrations by Billy Roberts, NREL

In the U.S., offshore transmission lines would be almost entirely in federal waters, potentially avoiding many of the conflicts associated with onshore projects, though it would still face challenges.

Challenges and next steps

Building an offshore grid will require some important changes.

First is changing government incentives. The federal investment tax credit for offshore wind, which covers at least 30% of the upfront capital cost of a project, does not currently help pay for coordinated transmission designs.

Second, planning needs to take everyone’s concerns into account from the beginning. While the overall benefits of coordinated transmission designs outweigh overall costs, who receives the benefits and who bears the costs matters. For example, more expensive power generators could earn less, and some communities feel threatened by offshore development.

Third, greater coordination will be needed among everyone involved to dispatch power to and from the regional grids. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s recent Order 1920, requiring power providers to plan for future needs, may serve as a blueprint, but it does not apply to interregional projects, such as an offshore transmission backbone connecting over a dozen states across three regions.

Several New England states are seeing economic growth from the offshore wind industry. Here, blades are prepared for shipping at a pier in New London, Conn. Elizabeth J. Wilson, CC BY-ND

The U.S. reached an important milestone in March 2024 with the completion of South Fork Wind, the country’s first utility-scale wind farm, bringing U.S. offshore wind power capacity to nearly 200 megawatts. Eight more projects are under construction or approved for construction. Once built, they would bring installed capacity to over 13 gigawatts, roughly the same as three dozen coal-fired power plants.

An offshore transmission backbone could support offshore wind development and the East Coast’s energy needs for generations to come.

The authors of this article:

Research Associate in Environmental Studies, Dartmouth College

Research Scholar, Ralph O’Connor Sustainable Energy Institute, Johns Hopkins University

Professor of Environmental Studies, Dartmouth College

Professor of Industrial Engineering Applied to Energy Policy, UMass Amherst

Disclosure statement

Abraham Silverman receives funding from Clean Grid Initiative. Abe previously worked at the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities on offshore wind and transmission matters. Abe also facilitates the Northeast States Collaborative on Interregional Transmission, which includes discussion of offshore wind and transmission matters.

Elizabeth J. Wilson receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the Sloan Foundation.

Erin Baker receives funding from the National Science Foundation, U.S. EPA, and U.S. Department of Energy

Tyler Hansen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

‘Between expectation and desire’

“She’s a luscious morsel,’’ by Saxtons River, Vt.-based artist Whitney Barrett at Canal Street Gallery, Bellows Falls, Vt.

He says:

“Using pattern, mark making and collage, I have been integrating found text and hybrid/abstracted human figures in static poses. These pieces explore questions of identity, story, and how we present to the outside world. I am interested in the way stories are told and implied, assumptions and miscommunication, as well as the tension between expectation and desire.’’

Amy Maxmen: Battling bird flu in the heat as U.S. struggles to contain outbreak

— Photo by Snowmanradio

“If a farm worker gets severely ill or dies from an H5N1 infection, it will be a stain on U.S. public health that we didn’t do more with the tools we have.’’

— Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University

Six people who work at a poultry farm in northeastern Colorado have tested positive for the bird flu, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported July 19. This brings the known number of U.S. cases this year to 10.

The workers were likely infected by chickens, which they had been tasked with killing in response to a bird flu outbreak at the farm. The endeavor occurred amid a heat wave, as outside temperatures soared to 104 degrees Fahrenheit.

“The barns in which culling occurs were no doubt even hotter,” said CDC principal deputy director Nirav Shah at a July 16 press briefing. Wearing N95 respirators, goggles, and other protective gear was a challenge. Industrial fans whipped feathers around the facility that could have carried the virus, Shah added.

In this environment, the farmworkers collected hundreds of chickens by hand and placed them into carts where they could be killed by carbon dioxide gas within two minutes.

“If a farm worker gets severely ill or dies from an H5N1 infection, it will be a stain on U.S. public health that we didn’t do more with the tools we have,” Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, posted on X. “You don’t send farm workers in to cull H5N1 infected birds without goggles and masks. Period. If it’s too hot to wear those protections, it’s too hot to cull. We need vaccines to be made available to farm workers. We have to stop gambling with peoples’ lives.”

More than 99 million chickens and turkeys have been infected with a highly pathogenic strain of the bird flu that emerged at U.S. poultry farms in early 2022. Since then, the federal government has compensated poultry farmers more than $1 billion for destroying infected flocks and eggs to keep outbreaks from spreading.

As summer temperatures rise across the country, Shah said, the agency is contending with how to offer farmworkers “safety from the virus, as well as safety from extreme heat.”

The H5N1 bird flu virus has spread among poultry farms around the world for nearly 30 years. An estimated 900 people have been infected by birds, and roughly half have died from the disease.

The virus made an unprecedented shift this year to dairy cattle in the U.S. This poses a higher threat because it means the virus has adapted to replicate within cows’ cells, which are more like human cells. The four other people diagnosed with bird flu this year in the U.S. worked on dairy farms with outbreaks.

Scientists have warned that the virus could mutate to spread from person to person, like the seasonal flu, and spark a pandemic. There’s no sign of that, yet.

So far, all 10 cases reported this year have been mild, consisting of eye irritation, a runny nose, and other respiratory symptoms. However, numbers remain too low to say anything certain about the disease because, in general, flu symptoms can vary among people with only a minority needing hospitalization.

The number of people who have gotten the virus from poultry or cattle may be higher than 10. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has tested only about 60 people over the past four months, and powerful diagnostic laboratories that typically detect diseases remain barred from testing for bird flu. Testing of farmworkers and animals is needed to detect the H5N1 bird flu virus, study it, and stop it before it becomes a fixture on farms.

Researchers have urged a more aggressive response from the CDC and other federal agencies to prevent future infections. Many people exposed regularly to livestock and poultry on farms still lack protective gear and education about the disease. And they don’t yet have permission to get a bird flu vaccine.

Nearly a dozen virology and outbreak experts recently interviewed by KFF Health News disagree with the CDC’s decision against vaccination, which may help prevent bird flu infection and hospitalization.

“We should be doing everything we can to eliminate the chances of dairy and poultry workers contracting this virus,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. “If this virus is given enough opportunities to jump from cows or poultry into people, it will eventually get better at infecting them.”

To understand whether cases are going undetected, researchers in Michigan have sent the CDC blood samples from workers on dairy farms. If they detect bird flu antibodies, it’s likely that people are more easily infected by cattle than previously believed.

“It’s possible that folks may have had symptoms that they didn’t feel comfortable reporting, or that their symptoms were so mild that they didn’t think they were worth mentioning,” said Natasha Bagdasarian, chief medical executive for the state of Michigan.

In hopes of thwarting a potential pandemic, the United States, United Kingdom, Netherlands, and about a dozen other countries are stockpiling millions of doses of a bird flu vaccine made by the vaccine company CSL Seqirus.

Seqirus’ most recent formulation was greenlighted last year by the European equivalent of the FDA, and an earlier version has the FDA’s approval. In June, Finland decided to offer vaccines to people who work on fur farms as a precaution because its mink and fox farms were hit by bird flu last year.

The CDC has controversially decided not to offer at-risk groups bird flu vaccines. Demetre Daskalakis, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told KFF Health News that the agency is not recommending a vaccine campaign at this point for several reasons, even though millions of doses are available. One is that cases still appear to be limited, and the virus isn’t spreading rapidly between people as they sneeze and breathe.

The agency continues to rate the public’s risk as low. In a statement posted in response to the new Colorado cases, the CDC said its bird flu recommendations remain the same: “An assessment of these cases will help inform whether this situation warrants a change to the human health risk assessment.”

Amy Maxmen is a journalist for Kaiser Family Foundation Health News.

‘Microcosm’

Archival photo of Tenants Harbor Light

“I thought to live on an island was like living on a boat. Islands intrigue me. You can see the perimeters of your world. It’s a microcosm.’’

— Jamie Wyeth (born 1946), American painter many of whose works are based on what he has seen on the Maine Coast, notably at Tenants Harbor and Monhegan Island. His base of operations is Tenants Harbor Light.

Monhegan Island in 1909

Bridge bathos and beauty

Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge, in foreground, and Bourne Bridge in December 1935 after soon after they were completed. The Sagamore Bridge is out of sight here.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Most readers have driven on the two vehicle bridges – the Sagamore and Bourne -- over the spectacular Cape Cod Canal and noticed that the Feds built them both in only two years – 1933-1935 – with equipment and building materials inferior to what we have now. The current bridges have been impressively sturdy, though driving on the two-way spans, with their too-narrow lanes, can be unnerving. Clench your teeth and look straight ahead!

There’s also the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge, also built in 1933-1935, allowing a bit of freight and seasonal passenger service on the Cape.

So the decision has been made to replace the bridges, via a combination of federal and state money. Officials say that construction of the new Sagamore Bridge won’t start until 2027 and building of a new Bourne Bridge until 2029. The hope is to complete the Sagamore Bridge by 2034 and the Bourne Bridge maybe by 2036. The total cost is projected to be $4.5 billion.

(Who of us old folks will be around to see the new bridges, and would we be too decrepit to drive on them? Would the new bridges make things, worse, not better, traffic-wise, by drawing even more people to the Cape?)

It’s very difficult to do big projects in America because of too many sometimes conflicting jurisdictions, too many permitting layers and the sometimes paralyzing fear of litigation. It would be nice if officials used the new bridges as a nation-leading example of how to speed up big projects.

I also thought of how more railroad service to the Cape would help cut down on what is often from May to October’s horrific car traffic going to and from what is a man-made island.

Likewise, Aquidneck Island would be more habitable if a railroad(s) – MBTA and/or Amtrak -- connected it with the outside world and took a lot of vehicles off the road. New bridges would, of course, be needed. The terminus would be at Thames Street in Newport, whence tourists could easily walk to many of the City by the Sea’s famous sights and sites. Alas, that’s more billions of bucks!

‘It would be energizing and uplifting if the new bridges we do put up in such watery places as Rhode Island and Massachusetts were more than just for vehicles. They could be lively attractions, providing dramatic views for pedestrians and bicyclists. There could be plantings on them and maybe even snack bars. They could become like public squares, albeit with anti-suicide fences….

A CapeFLYER train, providing seasonal service, crosses the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge on the Cape Main Line in 2013.

— Photo by Pi.1415926535

‘Ebb and flow’

— Photo by Snowmanradio

“What I remember is the ebb and flow of sound

That summer morning as the mower came and went

And came again, crescendo and diminuendo….’’

— From “The Sound I listened For,’’ by Robert Francis (1901-1987), Amherst, Mass.-based poet

A place to pay tribute to your (usually)most-loyal friends

Inside the Dog Chapel, at the Stephen Huneck Gallery, on Dog Mountain, in St. Johnsbury, Vt.

Outside of the Dog Chapel

— Photo by User:Dismas

Andrew Warburton: Where pixilated' came from

English pixies playing on the skeleton of a cow.

— John D. Batten. c.1894

Front Street in Marblehead around the turn of the 20th Century.

1916 photo

Text excerpted from The New England Historical Society Web site

“When I say that the town of Marblehead on Massachusetts’s North Shore is unlike other coastal Massachusetts towns, I’m not simply referring to the fact that it’s teeming with fairies and pixies (which it is). Isolated from the state’s highway system on a remote peninsula, the town has always boasted a most unorthodox history.

“Think of it as the black sheep of Colonial New England. Whereas Puritans founded the surrounding settlements of Salem, Peabody, and Danvers to be pure and godly communities, Marblehead’s beginnings were more down to earth. According to historians Priscilla Sawyer Lord and Virginia Clegg Gamage, ‘irreligious settlers’ and ‘adventurous fishermen’ founded the town to escape the harsh dictates of Puritanism while making a living catching fish. In about 1629, these humble but industrious early settlers headed south east to a peninsula where the Naumkeag Tribe lived. They coexisted peacefully with the tribe while establishing the sleepy fishing village we know today.

“Over the next few hundred years, Marblehead saw an influx of fairy-acquainted immigrants from Scotland and the fishing regions of South West England: Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, and Somerset. According to the historian Samuel Roads, immigration from England’s South West accounted for what he called Marblehead’s ‘idiomatic peculiarities….’’’

Lilian Dove: Tagging seals with sensors helps scientists track changes in currents and climate

Weddell seal coming up for air in the Southern Ocean.

PROVIDENCE, R.I.

A surprising technique has helped scientists observe how Earth’s oceans are changing, and it’s not using specialized robots or artificial intelligence. It’s tagging seals.

Several species of seals, such Weddell seals, live around and on Antarctica and regularly dive more than 100 meters in search of their next meal. These seals are experts at swimming through the vigorous ocean currents that make up the Southern Ocean. Their tolerance for deep waters and ability to navigate rough currents make these adventurous creatures the perfect research assistants to help oceanographers like my colleagues and me study the Southern Ocean.

Seal sensors

Researchers have been attaching tags to the foreheads of seals for the past two decades to collect data in remote and inaccessible regions. A researcher tags the seal during mating season, when the marine mammal comes to shore to rest, and the tag remains attached to the seal for a year.

A researcher glues the tag to the seal’s head – tagging seals does not affect their behavior. The tag detaches after the seal molts and sheds its fur for a new coat each year.

The tag collects data while the seal dives and transmits its location and the scientific data back to researchers via satellite when the seal surfaces for air.

Scientists attach a tag to a seal after it is safely tranquilized. Etienne Pauthenet

First proposed in 2003, seal tagging has grown into an international collaboration with rigorous sensor accuracy standards and broad data sharing. Advances in satellite technology now allow scientists to have near-instant access to the data collected by a seal.

New scientific discoveries aided by seals

The tags attached to seals typically carry pressure, temperature and salinity sensors, all properties used to assess the ocean’s rising temperatures and changing currents. The sensors also often contain chlorophyll fluorometers, which can provide data about the water’s phytoplankton concentration.

Phytoplankton are tiny organisms that form the base of the oceanic food web. Their presence often means that animals such as fish and seals are around.

The seal sensors can also tell researchers about the effects of climate change around Antarctica. Approximately 150 billion tons of ice melts from Antarctica every year, contributing to global sea-level rise. This melting is driven by warm water carried to the ice shelves by oceanic currents.

With the data collected by seals, oceanographers have described some of the physical pathways this warm water travels to reach ice shelves and how currents transport the resulting melted ice away from glaciers.

Seals regularly dive under sea ice and near glacier ice shelves. These regions are challenging, and can even be dangerous, to sample with traditional oceanographic methods.

The amount of excess heat (shown as energy) that the upper ocean (above 700 meters), deep ocean (below 700 meters), atmosphere and Earth have been taking up has increased over the past few decades. All values are relative to 1971, and uncertainty in the ocean values dominates the total uncertainty (black dotted line). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Across the open Southern Ocean, away from the Antarctic coast, seal data has also shed light on another pathway causing ocean warming. Excess heat from the atmosphere moves from the ocean surface, which is in contact with the atmosphere, down to the interior ocean in highly localized regions. In these areas, heat moves into the deep ocean, where it can’t be dissipated out through the atmosphere.

The ocean stores most of the heat energy put into the atmosphere from human activity. So, understanding how this heat moves around helps researchers monitor oceans around the globe.

Seal behavior shaped by ocean physics

The seal data also provides marine biologists with information about the seals themselves. Scientists can determine where seals look for food. Some regions, called fronts, are hot spots for elephant seals to hunt for food.

In fronts, the ocean’s circulation creates turbulence and mixes water in a way that brings nutrients up to the ocean’s surface, where phytoplankton can use them. As a result, fronts can have phytoplankton blooms, which attract fish and seals.

While we traditionally consider the ocean to be blue, it can actually appear green from space because of phytoplankton blooms. Currents can stretch out these blooms, and seals prefer to feed in these locations.

Scientists use the tag data to see how seals are adapting to a changing climate and warming ocean. In the short term, seals may benefit from more ice melt around the Antarctic continent, as they tend to find more food in coastal areas with holes in the ice. Rising subsurface ocean temperatures, however, may change where their prey is and ultimately threaten seals’ ability to thrive.

Seals have helped scientists understand and observe some of the most remote regions on Earth. On a changing planet, seal tag data will continue to provide observations of their ocean environment, which has vital implications for the rest of Earth’s climate system.

Lilian Dove is a post-doctoral fellow of oceanography at Brown University.

Lilian Dove does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Blue falls

“Plumb 36 C (Leaves of Grass)’’ (UV polymer on aluminum), by Henry Mandell, at Lanoue Gallery, Boston.