Rhode Island might soon ban captive hunting

Female white-tailed deer (a very common species in New England) with tail in alarm posture. There’s worry that bringing in elk and other species from other parts of American could introduce diseases.

— Photo by D. Gordon E. Robertson

Excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Rob Smith

“Five years after the plan was first introduced, state lawmakers are on the cusp of banning captive hunting practices in Rhode Island.

“Also known as ‘canned hunting,’ captive hunting refers to the practice of importing wild animals into a specific, fenced-in location for the intended purpose of hunting game that, in theory, cannot escape. Critics of the practice have argued that legalizing captive hunting would be a backdoor way into introducing wild game and even diseases that currently have no presence in Rhode Island, and would interrupt local hunters’ longstanding free-chase traditions….

“Identical bans (S2732A/H7294A) were introduced in the House and Senate earlier this year. ..

Tres gay in Hartford

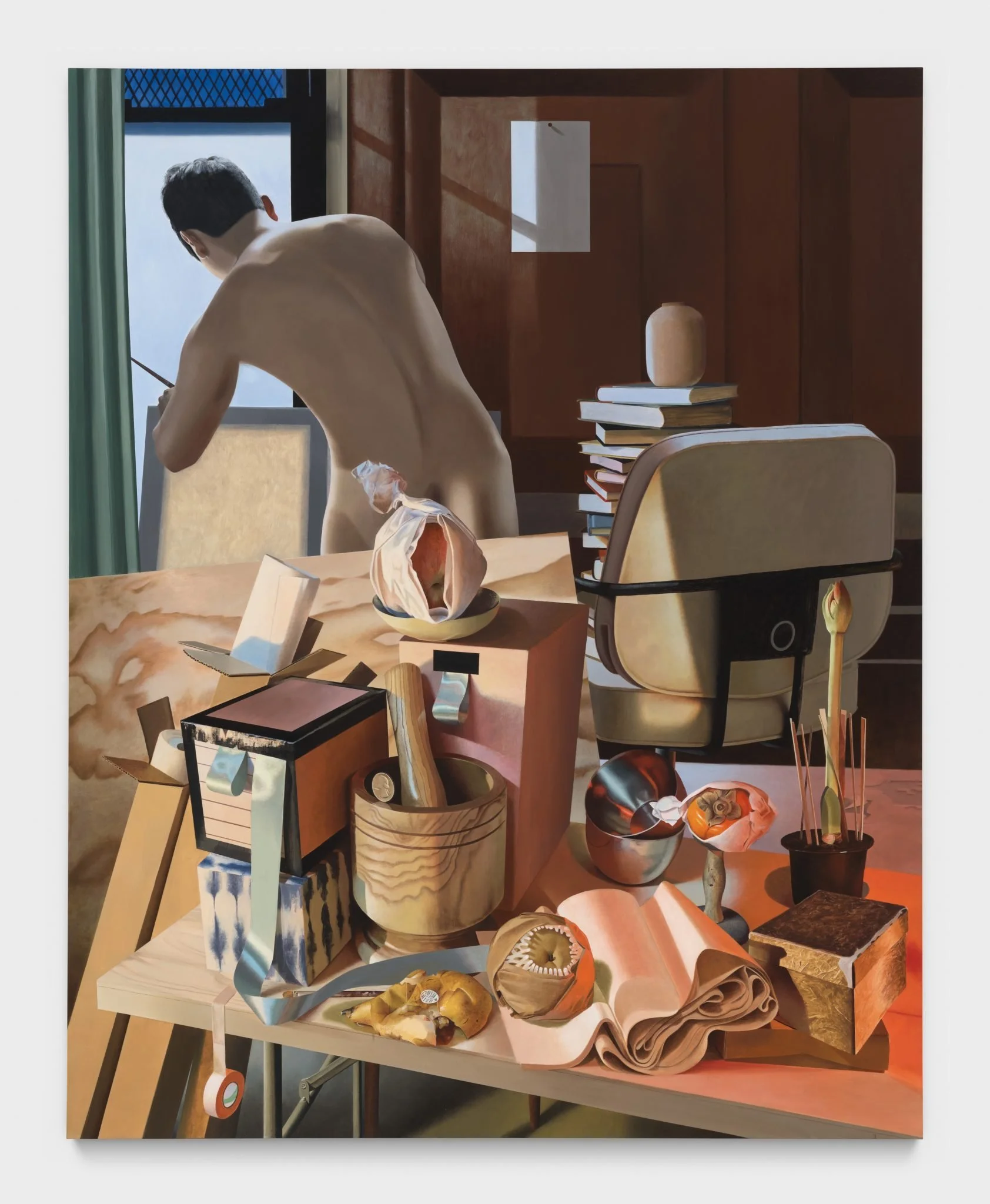

“Studio Still Life” (acrylic on wood panel), by New York painter Kyle Dunn, in his show Matrix 194, at the Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford, June 7-Sept. 1

- Courtesy of the Artist and P·P·O·W, New York

- Photo by JSP Art Photography

The museum says:

“Kyle Dunn’s luminous paintings dramatize themes of intimacy and alienation. In alluring domestic scenes, men perform everyday rituals against the backdrop of the big city, whose glow shines through the windows of their small apartments. Some of his composite figures sit in quiet contemplation, while others are seemingly caught during romantic encounters. Spatially ambiguous settings collapse interior and exterior worlds—both physical and psychological—inviting us to question the boundaries between public and private, individual and collective.’’

Why to be a vegan?

“Prosciutta” (clay, glaze, acrylic and epoxy), by Boston area artist Joe Caruso, in the show DIG, at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through Aug. 11

— Image courtesy of Art Complex Museum

The museum says that DIG features the work of Joe Caruso, Jennifer Liston Munson, Palamidessi and Marsha Odabashian in a show that "recalls traditions, events, and customs across a range of cultures.’’ The artists in explore "what makes us human" by exploring the past and how it connects to the future. The show "values, preserves and calls attention to what came before so we can learn from the past as we cope with the present and prepare for the future."

Llewellyn King: You’ll feel better with a bit of silken style around your neck

Archibald Cox (1912-2004), who served as Watergate scandal special prosecutor, solicitor general and Harvard Law School professor, wearing, as usual, a bow tie — a popular accessory of New England WASP’s.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I admire Ben Mankiewicz, host of Turner Classic Movies. He is the man we all think we are in our dreams: handsome, urbane, authoritative and oh-so charming — a member of one of the great families of film, an aristocrat of that realm.

I would like to look like Ben; his job is appealing, too.

But wait, Ben has suffered a savage downfall. He isn’t the man he used to be to me. I nearly fell off the couch when I saw Ben, an inspiration to men, introducing a movie without his necktie.

Yes, Ben was open-collared in a suit, looking a little like an unmade bed, which is what most men look like when pursuing the current fashion of no necktie.

Shock Horror! Another bastion of masculinity has fallen.

The problem — and I aver this to be an unassailable truth — is men wearing dress shirts without ties look less than their best. If they have a bit of age on them, a lot less than their best.

The dress shirt, which hasn’t been replaced, is designed for a necktie, long or in a bow. Without them men look diminished, incomplete, as though they had to leave the house with no time to finish dressing.

Let me state that the necktie is indeed a useless piece of clothing, like other dress items of the past: spats, watch chains and detached collars. The passing of none of these do I regret – but ties? Cry, the lost masculine adornment of yesteryear.

The necktie was something a man could glory in. Tying a long tie and throwing the long end over the short end always gave me the same feeling as mounting my horse; when my right leg cleared the saddle, I knew something good was going to happen. A great day in the Virginia countryside usually.

Ties were something to treasure; fine silk, great patterns, elegance written with restraint. Just long enough, just obvious enough, conveying refinement and masculine savoir faire.

Now men are running around open-necked in shirts that weren’t designed to be worn that way.

Have a care for the great names in ties, those who saved us on Father’s Day, Christmas and birthdays, are losing money or gone to other pursuits.

Have a care for Hermes, Liberty, Tyrwhitt, Brioni, Fumagalli, Brooks Brothers and all those who created lovely things for the neck out of silk, finely woven wool or linen.

Just the sight of the box lit up the male face, ensuring the giver some future preferment or an extra helping at the table. The power of the tie was formidable — as Omar Khayyam, the Persian poet, might have said, it could transmute life’s leaden metal into gold.

At least it kept Dad smiling through some de rigueur family events. Ever noticed how he slipped off to the bathroom not to engage the porcelain but to admire himself in the mirror with the new gift around his neck?

Not so long ago, great restaurants had spare ties for guests who showed up without them. Now that is over.

The last holdout I know of is the Metropolitan Club in Washington. I have been to two events there recently and the hosts thought it wise to advise their guests on dress etiquette: ties and no white-soled shoes. But no cravats or ascots as well. Strange.

I am hoping the cravat or its cousin the ascot will come back vigorously. It will save those master craftspeople who dyed silk, wove wool and shaped their handiwork over canvas to adorn men’s necks of no practical value but so dressy, so uplifting, so defining.

Give a cravat and tell the man in your life or your father, “You look like David Niven.”

Come to think of it, I bet that Ben Mankiewicz looks stupendous wearing a cravat.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Never-ending work

“Mending Nets, F/V Miss Trish II” (photograph), by Paul Cary Goldberg, at Manship Arts and Residence, Gloucester, Mass.

Why they stayed

The path along the Charles River on the Esplanade, in Boston.

—Photo by Ingfbruno

—Photo by Milos Milosevic

Kim Stanley Robinson (born 1952), American writer

John O. Harney: The Rose Kennedy Greenway bursts into bloom

The Rose Kennedy Greenway

Some sights on the Greenway:

BOSTON

I began volunteering as a phenologist on the Rose Kennedy Greenway, in downtown Boston, in spring 2023 and returned a few weeks ago for the 2024 season.

Peppermint-striped tulips were flowering along Pearl Street. Grape hyacinths create purple blankets; anemones whitish carpets. Hellebores that made an early spring show with dusty green-white and pink flowers were already fading. In one spot, it looked like a resting animal has flattened a bed of irises and allium.

Last year, all narcissuses were daffodils to my hardly trained eye. This year, I think I was seeing poeticus with white petals and yellow and reddish-outlined centers, sagitta with yellow double flowers around an orange tube and pheasants eye with its complex yellow and orange center. But I could be wrong.

Many plants were leafing but not yet flowering: irises, alliums, yellow- and red-twig dogwoods, lamb’s ear, roses, penstemon leafing purplish, dracunculus, astilbes, peonies, tickseed in a tough place along Purchase Street, nepeta, grasses near the tunnel vent still yellowish but with a few strands of green, achillea, aruncus and hosta shoots I’ve watched turn from young purplish shoots to fat green leaves reminiscent of a Rousseau painting. Few veggies or fruits visible. No sunflowers yet.

(By the way, in my old job as the executive editor of the New England Journal of Higher Education I was in charge of editorial style rules … things such as when to capitalize words, including names of plants I suppose. It always seemed too arbitrary, and, in retirement, I don’t bother.)

At the corner of Congress Street, I notices a mat of creeping blue phlox with its many light blue-purplish flowers—not, to my eye at least, the pink phlox associated with April 2024’s pink moon.

Speaking of such connections, serviceberry shrubs (also known as shadbushes) had flowered, mirroring the season when shad fish run up New England rivers and, for me, the promise of the delicious season of shad roe.

Jumping out to me on Parcel 21 was a humble dandelion. I note that, sure, it’s a pest, but it’s flowering full yellow, so it gets a 3 in the Greenway ranking system that I’ve never quite got my head around, as they say. The “best” rank among 1 to 5 is 3, not the lowest or highest, but 3 for full flower … peak.

A few other observations …

Maybe it’s the natural magnificence of the Greenway that somehow makes man-made signs catch my eye. Even the troubles of the world pierce the serenity of the park. Take the spot near the North End where a Priority Mail sticker on a park sign reads: “FROM: POWER TO THE RESISTANCE TO: GLOBALIZE THE INTIFADA’’.

Then the welcome reminder of “No mow May on the Greenway … The Greenway Conservancy is participating in Plantlife’s No Mow May initiative to support local pollinators, reduce lawn inputs, and grow healthier lawns. Certain areas of the Greenway will not be mowed in May.” A noble goal for homeowners too.

Nice to see a rare nametag on the Greenway identifying the good-looking and great-smelling Koreanspice viburnum. I had proposed such tagging last year in my piece on A Volunteer Life. Undoubtedly, others made similar suggestions. Still, I naively congratulated myself for any role in the tag, as two houseless people tried to tell me that there are apps on the market that ID plants. Immersed in my headphones, I reacted dismissively. Like a jerk, really. Quickly realizing my rudeness, I returned and apologized. These gardens are theirs more than mine.

With the helpful tips from the houseless on my mind and my interest in signs piqued, I also noticed for the first time, in Parcel 22, a green sign reading: “PARK CLOSED, 11 PM – 7 AM Trespassers will be prosecuted.”

With its tunnel vent, Parcel 22 is a big part of my Greenway life partly for its proximity to the park’s edible and pollinator gardens and Dewey Square and the Red Line plaza. The tunnel vent holds the Greenway mural. A sign reads: “What has this mural meant to you?” A mailbox is supplied for reader comments. One of the recent murals depicted a youth from the city, who critics insisted was a Middle Eastern terrorist. (Murals are dangerous business in New England. See here and here.)

And now to presumably dazzle the Greenway: colorful coneflowers, sturdy Joe Pye weeds, beebalm, furry salvia, white fringe trees, flowering black elderberries and hydangeas.

Jay L. Zagorsky: What about all that small change we leave at airports?

TSA officer at airport with a tray of prohibited items.

BOSTON

Should the U.S. get rid of pennies, nickels and dimes? The debate has gone on for years. Many people argue for keeping coins on economic-fairness grounds. Others call for eliminating them because the government loses money minting low-value coins.

One way to resolve the debate is to check whether people are still using small-value coins. And there’s an unlikely source of information showing how much people are using pocket change: the Transportation Security Administration, or TSA. Yes, the same people who screen passengers at airport checkpoints can answer whether people are still using coins – and whether that usage is trending up or down over the years.

Each year, the TSA provides a detailed report to Congress showing how much money is left behind at checkpoints. A decreasing amount of change would suggest fewer people have coins in their pockets, while a steady or increasing amount indicates people are still carrying coins.

The latest TSA figure shows that during 2023, air travelers left almost US$1 million in small change at checkpoints. This is roughly double the amount left behind in 2012.

At first glance, this suggests more people are carrying around and using coins. But as a university researcher who studies both travel and money usage – as well as a keen observer of habits while lining up at airport checkpoints – I know the story is more complicated than these numbers suggest.

What gets left behind?

More than 2 million people fly each day in the U.S., passing through hundreds of airport checkpoints manned by the TSA. Each flyer going through a checkpoint is asked to place items from their pockets such as wallets, phones, keys and coins in either a bin or their carry-on bag. Not everyone remembers to pick up all their items on the other side of the scanner. About 90,000 to 100,000 items are left behind each month, the TSA estimates.

For expensive or identifiable items such as cellphones, wallets and laptops, the TSA has a lost-and-found department. For coins and the occasional paper bills that end up in the scanner bins, TSA has a different procedure. It collects all that money, catalogs the amount and periodically deposits it into a special account that the TSA uses to improve security operations.

That money adds up, with travelers leaving behind almost $10 million in change over the past 12 years.

The amount of money left varies by airport. JFK International Airport in New York City is consistently in one of the top slots for most money lost, with travelers leaving almost $60,000 behind in 2022. Harry Reid International Airport, which serves Las Vegas, also sees a large amount of money left behind. Love Field in Dallas, headquarters of Southwest Airlines, is often near the bottom of the list, with only about $100 lost in 2022.

People lose money while going through security for a few reasons. First, some cut it close getting to the airport, and in their rush to avoid missing their plane, they don’t pick up everything after screening. Second, sometimes TSA lines are exceptionally long, leaving people to again scramble to make up time. And finally, TSA checkpoints are often confusing and noisy places, especially for new or infrequent travelers. Making it more confusing is that some airports have bins featuring advertisements, which distract travelers who only quickly glance to check for all their items.

How much is lost?

TSA keeps careful track of how much is lost because the agency is allowed to keep any unclaimed money left behind at checkpoints. TSA records show people left behind half a million dollars in 2012. This rose to almost a million in 2018. The drop in travel due to the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the figure back to half a million in 2020. In 2023, people left $956,000.

These raw figures need two adjustments to accurately track trends in coins lost. First, the numbers need to be adjusted for inflation. From 2012 to 2023, the consumer price index rose by 33%. This means a dollar of change in 2012 purchased one-third more than it did 12 years later.

Second, the number of people flying and passing through TSA screening has changed dramatically over time. In 2012, about 638 million people went through the checkpoints. By 2023, that had risen to 859 million people, which is about 1,000 people every 30 seconds across the entire U.S. when airports and checkpoints are open.

Adjusting for both inflation and the number of people screened shows no change in the amount of money lost. My calculations show back in 2012 about $1.10 in coins was lost for every 1,000 people screened. In 2023, about one penny more, or $1.11, was lost per 1,000.

The peak year for money being lost was 2020, when $1.80 per 1,000 people was left behind. This was likely due to people not wanting to touch objects out of misplaced fear they could contact COVID-19. During the pandemic, people in general carried less money.

The world is increasingly using electronic payments. The data from TSA checkpoints, however, clearly shows people are carrying coins at roughly the same rate as back in 2012. This suggests Americans are still using physical money, at least for making small payments – and that the drive to get rid of pennies, nickels and dimes should hold off a while longer.

Jay L. Zagorsky is associate professor of markets, public policy and law at Boston University.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

Chased by spring

‘The Road North,’’ by Nora S. Unwin (1907-1982), at the Monadnock Center for History and Culture, Peterboro, N.H., through Sept. 28.

The gallery says:

Artist, engraver, illustrator and teacher, Nora S. Unwin had a long and successful career in her native England and her adopted home in New Hampshire. This retrospective exhibition features more than 80 works spanning her 60-year career.

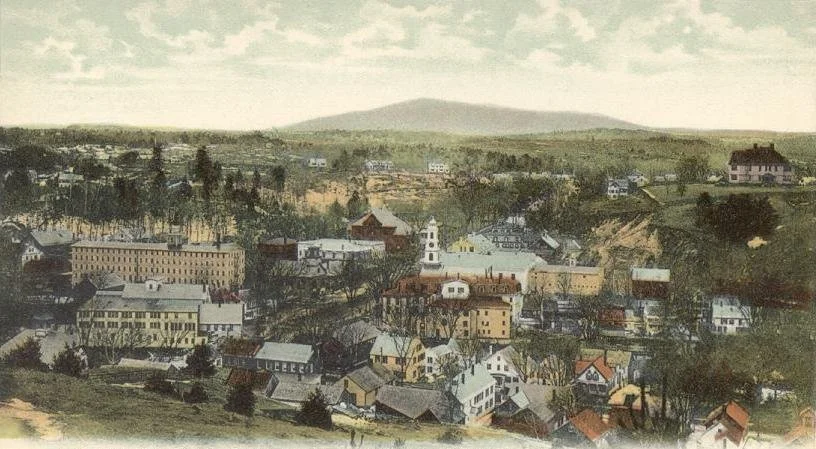

Peterboro in 1907.

Jessica Garcia: Insurance ‘bluelining’ for the vulnerable as they face disasters spawned by global warming

Flooding in Montpelier, Vt. on July11, 2023.

Via OtherWords.org

In an era of climate disasters, Americans in vulnerable regions will need to rely more than ever on their home insurance. But as floods, wildfires and severe storms become more common, a troubling practice known as “bluelining” threatens to leave many communities unable to afford insurance — or obtain it at any price.

Bluelining is an insidious practice with similarities to redlining — the notorious past government-sanctioned practice of financial institutions denying mortgages and credit to Black and brown communities, which were often marked by red lines on map.

These days, financial institutions are now drawing “blue lines” around many of these same communities, restricting such services as insurance based on environmental risks. Even worse, many of those same institutions are bankrolling those risks by funding and insuring the fossil fuel industry.

Originally, bluelining referred to blue-water flood risks, but it now includes such other climate-related disasters as wildfires, hurricanes, and severe thunderstorms, all of which are driving private-sector decisions. (Severe thunderstorms, in fact, were responsible for about 61 percent of insured natural catastrophe losses in 2023.)

In the case of property insurance, we’re already seeing insurers pull out of entire states, such as California and Florida. The financial impacts of these decisions are considerable for everyone they affect — and often fall hardest on those in low-income and historically disadvantaged communities.

A Redfin study from 2021 illustrated that areas previously affected by redlining are now also those prone to flooding and higher temperatures, a problem compounded by poor infrastructure that fails to mitigate these risks. This overlap is not a coincidence but a further consequence of systemic discrimination and disinvestment.

This financial problem exists no matter where you live. In 2024, the national average home-insurance cost has risen about 23 percent above the cost of similar coverage last year. Homeowners across more and more states are left grappling with soaring premiums or no insurance options at all. And the lack of federal oversight means there is little uniformity or coordination in addressing these retreats.

This situation will demand a radical rethink of how we approach investing in our communities based on climate risks. For one thing, financial institutions must pivot from funding fossil fuel expansion to investing in renewable energy, natural climate solutions, and climate resilience, including infrastructure upgrades.

What about communities in especially vulnerable areas?

One strategy is community-driven relocation and managed retreat. By relocating communities to low-risk areas, we not only safeguard them against immediate physical dangers but also against ensuing financial hardships. Additionally, preventing development in known high-risk areas can significantly decrease financial instability and economic losses from future disasters.

As part of this strategic shift, financial policies must be realigned. We need regulations that compel financial institutions to manage and mitigate financial risk to the system and to consumers. We also need them to invest in affordable housing development that is energy-efficient, climate-resilient, and located in areas less susceptible to climate change in the mid- to long-term.

Meanwhile, green infrastructure and stricter energy efficiency and other resilience-related building codes can serve as bulwarks against extreme temperatures and weather events.

The challenge of bluelining offers us an opportunity to forge a path towards a more resilient and equitable society. We owe it to the future generations to do more than just adapt to climate change. We also need to confront and overhaul the systems that harm our climate. The communities most exposed to climate change deserve no less.

Jessica Garcia is a senior policy analyst for climate finance at Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund.

Island skeletons

‘‘Tumblehome,’’ by Peter Ralston, a Rockport, Maine-based photographer and gallery owner.

“It was the first time I had walked that end of the island {Matinicus} and I was deeply moved by the old fishing camps up there. No cellar holes, just decaying remnants of what was once a thriving little seasonal community.

“The place reeked of the past and I wandered in a reverie, surrounded by the evidence of so many lives lived and, now, gone.

“I beheld this particular juxtaposition of buildings and that was that.’’

Matinicus Isle Harbor in about 1908. The island is about 20 miles off the mainland. With an official population of 53, it’s the farthest out inhabited land off the U.S. East Coast, and is both a year-round community and a summer colony.

Trying to identify New England’s oldest golf clubs

The imposing clubhouse of the Newport Country Club

Excerpted text from aNew England Historical Society article.

“In 1728, Royal Governor William Dummer arrived in Massachusetts with nine ‘goffe clubs,’ but it would be another 150 years before golf clubs formed in New England.

“But to name the oldest golf clubs in New England is to invite controversy. Can a golf club claim to be the oldest if it started out as a boat or a tennis club and later added a golf course?

“We relied on the U.S. Golf Association’s list of the oldest golf clubs in America. However, we chose the oldest golf clubs in each state according to the year the golf course was built.’’

Turbulent world

“Cyano-Collage 191,’’ (collaged cyanotypes and Xuan paper with acrylic gel and acrylic, mounted on aluminum board), by Wu Chi-Tsung, at the Worcester Art Museum

Bancroft Tower Castle, in Worcester

— Photo by Anatoli Lvov

Chris Powell: Hartford’s new archbishop eyes the poverty factory

Archbishop Christopher J. Coyne

Cathedral of Saint Joseph in Hartford

— Photo by Sage Ross

MANCHESTER, Conn.

When he was installed two weeks ago, Hartford’s new Catholic archbishop, Christopher J. Coyne, said he has several big objectives, though he conceded that with two of them he may be dreaming.

Coyne’s most practical objective is simply restoring the local church and regaining parishioners. "In recent years," Coyne said, "we have given folks no shortage of causes to walk away from the faith -- parish closings, the abuse scandal and associated betrayals by leaders who should have known and done better, and pastoral approaches that at times have done more to judge people than serve them."

The archbishop can’t undo those scandals but he can be candid about them and make sure that the wrath of God quickly falls -- publicly -- on any agents of the archdiocese who betray their trust.

As for unhappy judgments on people, archbishops are stuck with church doctrines that many think contradict modernity, such as the refusal to ordain women or sanction same-sex relationships. Given the conservative bent of the places where the church is growing, those doctrines are unlikely to be changed soon.

Not that modernity is always right. Indeed, the basic Catholic morality of old is less primitive than today’s morality of anything goes. It wasn’t entirely because of religious doctrine, but Connecticut was better before state government started pushing gambling and marijuana on the public and pretending that men can be women and vice-versa.

Sad as Catholic parish closings are, ripping roots out of the community and leaving empty buildings as stark monuments to a vanished era, the decline in church membership requires closings and it has not been caused primarily by the scandals. While spirituality is not dead in the developed world, religious dogma is losing adherents fast. Perceptions of the divine today are much broader.

Fortunately the church has much to offer beyond dogma, starting with the Sermon on the Mount, and evangelical and non-denominational churches are growing. Catholic leaders might study their appeal.

In his inaugural remarks, the new archbishop noted that parish and school closings have left the church with many buildings that might be converted to inexpensive housing, of which Connecticut is desperately short. Of course this is easier said than done. While nearly everyone purports to want the state to have more housing, nearly everyone wants it built somewhere else. The fear of the underclass is real and often justified, as indicated by violent crime and terrible school performance in the cities.

The new archbishop has an idea about his new city, Hartford, a poverty factory where two high school students were shot to death the other day. His dreamiest objective is to restore Catholic schools in the city -- there are none left -- and make them tuition-free.

The excellence of Catholic schools is generally acknowledged. The schools have behavioral discipline and academic standards, which now are virtually prohibited in public schools. Unlike public schools, church schools can choose their students, but they use this freedom not to exclude but to pursue the most motivated students and parents.

Thus church schools can offer students an escape from the demoralization of city life, and with their better environment they can retain good staff while paying less than public schools.

Regional public "magnet" schools offer some escape as well but are still somewhat impaired in discipline and academic standards. They also impose more transportation burdens on students and parents than neighborhood schools.

In any case, as indicated by the litigation of the past quarter century over school segregation in Hartford, the city and other cities in Connecticut can use much more school choice. The return of Catholic schools could help provide it, but avoiding tuition would require money from somewhere.

A scholarship program from state government might provide it and educate students better and less expensively than government’s own system, but the teacher unions would never consent, and they run government in Connecticut. They have no interest in improving student performance, reducing poverty, and saving money. Only dreamers care about such stuff. Good for the new archbishop for being one.]

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

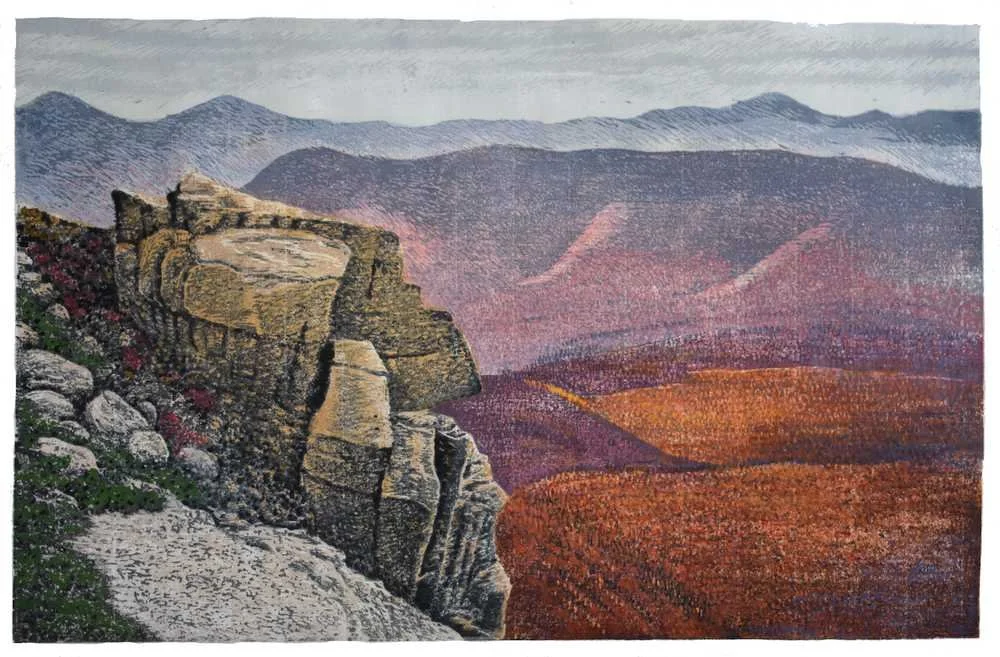

Elemental mountains

“Bond Cliff’ (color woodblock print), on Mt.. Bond in the White Mountains, by Fremont, N.H.-based artist Rick Garber, at New Leaf Gallery, Lyme, N.H.

Above the timber line on Mt. Bond.

Main Street in Fremont, N.H., in 1909.

Cheryl Platzman Weinstock: New federal approach being developed to address sometimes lethal maternal depression

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFF Health News)

BRIDGEPORT, Conn.

Milagros Aquino was trying to find a new place to live and had been struggling to get used to new foods after she moved to Bridgeport from Peru with her husband and young son in 2023.

When Aquino, now 31, got pregnant in May 2023, “instantly everything got so much worse than before,” she said. “I was so sad and lying in bed all day. I was really lost and just surviving.”

Aquino has lots of company.

Perinatal depression affects as many as 20% of women in the United States during pregnancy, the postpartum period, or both, according to studies. In some states, anxiety or depression afflicts nearly a quarter of new mothers or pregnant women.

Many women in the U.S. go untreated because there is no widely deployed system to screen for mental illness in mothers, despite widespread recommendations to do so. Experts say the lack of screening has driven higher rates of mental illness, suicide, and drug overdoses that are now the leading causes of death in the first year after a woman gives birth.

“This is a systemic issue, a medical issue, and a human rights issue,” said Lindsay R. Standeven, a perinatal psychiatrist and the clinical and education director of the Johns Hopkins Reproductive Mental Health Center.

Standeven said the root causes of the problem include racial and socioeconomic disparities in maternal care and a lack of support systems for new mothers. She also pointed a finger at a shortage of mental-health professionals, insufficient maternal mental-health training for providers, and insufficient reimbursement for mental health services. Finally, Standeven said, the problem is exacerbated by the absence of national maternity leave policies, and the access to weapons.

Those factors helped drive a 105% increase in postpartum depression from 2010 to 2021, according to the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

For Aquino, it wasn’t until the last weeks of her pregnancy, when she signed up for acupuncture to relieve her stress, that a social worker helped her get care through the Emme Coalition, which connects girls and women with financial help, mental health counseling services, and other resources.

Mothers diagnosed with perinatal depression or anxiety during or after pregnancy are at about three times the risk of suicidal behavior and six times the risk of suicide compared with mothers without a mood disorder, according to recent U.S. and international studies in JAMA Network Open and The BMJ.

The toll of the maternal mental-health crisis is particularly acute in rural communities that have become maternity care deserts, as small hospitals close their labor and delivery units because of plummeting birth rates, or because of financial or staffing issues.

The Maternal Mental Health Task Force — co-led by the Office on Women’s Health and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and formed in September to respond to the problem — recommended creating maternity care centers that could serve as hubs of integrated care and birthing facilities by building upon the services and personnel already in communities.

The task force will soon determine what portions of the plan will require congressional action and funding to implement and what will be “low-hanging fruit,” said Joy Burkhard, a member of the task force and the executive director of the nonprofit Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health.

Burkhard said equitable access to care is essential. The task force recommended that federal officials identify areas where maternity centers should be placed based on data identifying the underserved. “Rural America,” she said, “is first and foremost.”

There are shortages of care in “unlikely areas,” including Los Angeles County, where some maternity wards have recently closed, said Burkhard. Urban areas that are underserved would also be eligible to get the new centers.

“All that mothers are asking for is maternity care that makes sense. Right now, none of that exists,” she said.

Several pilot programs are designed to help struggling mothers by training and equipping midwives and doulas, people who provide guidance and support to the mothers of newborns.

In Montana, rates of maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancy are higher than the national average. From 2017 to 2020, approximately 15% of mothers experienced postpartum depression and 27% experienced perinatal depression, according to the Montana Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. The state had the sixth-highest maternal mortality rate in the country in 2019, when it received a federal grant to begin training doulas.

To date, the program has trained 108 doulas, many of whom are Native American. Native Americans make up 6.6% of Montana’s population. Indigenous people, particularly those in rural areas, have twice the national rate of severe maternal morbidity and mortality compared with white women, according to a study in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Stephanie Fitch, grant manager at Montana Obstetrics & Maternal Support at Billings Clinic, said training doulas “has the potential to counter systemic barriers that disproportionately impact our tribal communities and improve overall community health.”

Twelve states and Washington, D.C., have Medicaid coverage for doula care, according to the National Health Law Program. They are California, Florida, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Virginia. Medicaid pays for about 41% of births in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Jacqueline Carrizo, a doula assigned to Aquino through the Emme Coalition, played an important role in Aquino’s recovery. Aquino said she couldn’t have imagined going through such a “dark time alone.” With Carrizo’s support, “I could make it,” she said.

Genetic and environmental factors, or a past mental health disorder, can increase the risk of depression or anxiety during pregnancy. But mood disorders can happen to anyone.

Teresa Martinez, 30, of Price, Utah, had struggled with anxiety and infertility for years before she conceived her first child. The joy and relief of giving birth to her son in 2012 were short-lived.

Without warning, “a dark cloud came over me,” she said.

Martinez was afraid to tell her husband. “As a woman, you feel so much pressure and you don’t want that stigma of not being a good mom,” she said.

In recent years, programs around the country have started to help doctors recognize mothers’ mood disorders and learn how to help them before any harm is done.

One of the most successful is the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program for Moms, which began a decade ago and has since spread to 29 states. The program, supported by federal and state funding, provides tools and training for physicians and other providers to screen and identify disorders, triage patients, and offer treatment options.

But the expansion of maternal mental health programs is taking place amid sparse resources in much of rural America. Many programs across the country have run out of money.

The federal task force proposed that Congress fund and create consultation programs similar to the one in Massachusetts, but not to replace the ones already in place, said Burkhard.

In April, Missouri became the latest state to adopt the Massachusetts model. Women on Medicaid in Missouri are 10 times as likely to die within one year of pregnancy as those with private insurance. From 2018 through 2020, an average of 70 Missouri women died each year while pregnant or within one year of giving birth, according to state government statistics.

Wendy Ell, executive director of the Maternal Health Access Project in Missouri, called her service a “lifesaving resource” that is free and easy to access for any health care provider in the state who sees patients in the perinatal period.

About 50 health care providers have signed up for Ell’s program since it began. Within 30 minutes of a request, the providers can consult over the phone with one of three perinatal psychiatrists. But while the doctors can get help from the psychiatrists, mental health resources for patients are not as readily available.

The task force called for federal funding to train more mental health providers and place them in high-need areas like Missouri. The task force also recommended training and certifying a more diverse workforce of community mental health workers, patient navigators, doulas, and peer support specialists in areas where they are most needed.

A new voluntary curriculum in reproductive psychiatry is designed to help psychiatry residents, fellows, and mental health practitioners who may have little or no training or education about the management of psychiatric illness in the perinatal period. A small study found that the curriculum significantly improved psychiatrists’ ability to treat perinatal women with mental illness, said Standeven, who contributed to the training program and is one of the study’s authors.

Nancy Byatt, a perinatal psychiatrist at the University of Massachusetts Chan School of Medicine who led the launch of the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program for Moms in 2014, said there is still a lot of work to do.

“I think that the most important thing is that we have made a lot of progress and, in that sense, I am kind of hopeful,” Byatt said.

Cheryl Platzman Weinstock reports for KFF Health News. Her work is supported by a grant from the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation.

Llewellyn King: Three out-of-step environmental groups

Rachel Carson researching with Robert Hines on the New England coast in 1952. Her book Silent Spring helped launch the environmental movement.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Greedy men and women are conspiring to wreck the environment just to enrich themselves.

It has been an unshakable left-wing belief for a long time. It has gained new vigor since The Washington Post revealed that Donald Trump has been trawling Big Oil for big money.

At a meeting at Mar-a-Lago, Trump is reported to have promised oil industry executives a free hand to drill willy-nilly across the country and up and down the coasts, and to roll back the Biden administration’s environmental policies. All this for $1 billion in contributions to his presidential campaign, according to The Post article.

Trump may believe that there is a vast constituency of energy company executives yearning to push pollution up the smokestack, to disturb the permafrost and to drain the wetlands, but he has gotten it wrong.

Someone should tell Trump that times have changed and very few American energy executives believe — as he has said he does — that global warming is a hoax.

Trump has set himself not only against a plethora of laws, but also against an ethic, an American ethic: the environmental ethic.

This ethic slowly entered the consciousness of the nation after the seminal publication of Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson, in 1962.

Over time, concern for the environment has become an 11th Commandment. The cornerstone of a vast edifice of environmental law and regulation was the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. It was promoted and signed by President Richard Nixon, hardly a wild-eyed lefty.

Some 30 years ago, Barry Worthington, the late executive director of the United States Energy Association, told me that the important thing to know about the energy-versus-environment debate was that a new generation of executives in oil companies and electric utilities were environmentalists; that the world had changed and the old arguments were losing their advocates.

“Not only are they very concerned about the environment, but they also have children who are very concerned,” Worthington told me.

Quite so then, more so now. The aberrant weather alone keeps the environment front-and-center.

This doesn’t mean that old-fashioned profit-lust has been replaced in corporate accommodation with the Green New Deal, or that the milk of human kindness is seeping from C-suites. But it does mean that the environment is an important part of corporate thinking and planning today. There is pressure both outside and within companies for that.

The days when oil companies played hardball by lavishing money on climate deniers on Capitol Hill and utilities employed consultants to find data that, they asserted, proved that coal use didn’t affect the environment are over. I was witness to the energy-versus-climate-and-environment struggle going back half a century. Things are absolutely different now.

Trump has promised to slash regulation, but industry doesn’t necessarily favor wholesale repeal of many laws. Often the very shape of the industries that Trump would seek to help has been determined by those regulations. For example, because of the fracking boom, the gas industry could reverse the flow of liquified-natural-gas at terminals, making us a net exporter not importer.

The United States is now, with or without regulation, the world’s largest oil producer. The electricity industry is well along in moving to renewables and making inroads on new storage technologies like advanced batteries. Electric utilities don’t want to be lured back to coal. Carbon capture and storage draws nearer.

Similarly, automakers are gearing up to produce more electric vehicles. They don’t want to exhume past business models. Laws and taxes favoring EVs are now assets to Detroit, building blocks to a new future.

As the climate crisis has evolved so have corporate attitudes. Yet there are those who either don’t or don’t want to believe that there has been a change of heart in energy industries. But there has.

Three organizations stand out as pushing old arguments, shibboleths from when coal was king, and oil was emperor.

These groups are:

The Sunrise Movement, a dedicated organization of young people that believes the old myths about big, bad oil and that American production is evil, drilling should stop, and the industry should be shut down. It fully embraces the Green New Deal — an impractical environmental agenda — and calls for a social utopia.

The 350 Organization is similar to the Sunrise Movement and has made much of what it sees as the environmental failures of the Biden administration — in particular, it feels that the administration has been soft on natural gas.

Finally, there is a throwback to the 1970s and 1980s: an anti-nuclear organization called Beyond Nuclear. It opposes everything to do with nuclear power even in the midst of the environmental crisis, highlighted by Sunrise Movement and the 350 Organization.

Beyond Nuclear is at war with Holtec International for its work in interim waste storage and in bringing the Palisades plant along Lake Michigan back to life. Its arguments are those of another time, hysterical and alarmist. The group doesn’t get that most old-time environmentalists are endorsing nuclear power.

As Barry Worthington told me: “We all wake up under the same sky.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Looking for solace

“A Tear for October 7” (marble on burned wood), by Newton, Mass.-based sculptor Memy Ish-Shalom, in his show “Searching for Hope in Dark Times,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, June 6-30. He’s a native of Israel.

He says:

“In the past two years, we have all experienced and lived through devastating historical events. Such events have a significant impact on me as a human being and as an artist. I found myself compelled to respond to these tragic events through my art. In this show, I reflect on the atrocities and the collective trauma my friends and family in Israel experienced on October 7.

“These are, indeed, dark times. On troubled, sleepless nights, I find myself looking up at the sky, gazing at the moon, the stars, and the clouds, or looking down at the stones and rocks on the ground, in search for some solace in their enduring beauty. On other occasions, I take a deep look at people. Whenever I encounter people with courageous and optimistic spirits, I feel inspired and more hopeful.”

Revolutionary coverings

“Lil Glory’’ (fabric, polyester fill, fringe), by Natalie Baxter, in the show “Stiching the Revolution: Quilts as Agents of Change,’’ at the Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, Conn., opening May 19.

The show presents about 30 quilts from the museum’s collection, and loans from other New England institutions and contemporary artists. The exhibition pairs historic and modern quilts spanning over 200 years of production viewed as pivotal mediums that express potent beliefs and inspire important change.

Waterbury skyline from the west, with Union Station clock tower at left. The city was once known as the brass and clock / watch capital of America. New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, lived near Waterbury in 1962-66 and remembers the many factories still open, the toxic pollution of the Naugatuck River, which flowed through the city, and the necessity of walking up and down steep hills.

The multiplying uses of seaweed

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

When I was a kid living along Massachusetts Bay, we often saw seaweed (various species of marine macroalgae – kelp, etc.) as somewhat irritating. It could get in the way of fishing lines, and it would pile up on beaches in rank rows.

But seaweed, which, blessedly, grows rapidly, is looking better and better. It absorbs carbon dioxide, absorption that directly fights global warming, and it offsets a bit of ocean acidification caused by carbon dioxide from our fossil-fuel burning; it slows coastal erosion by weakening the force of waves in storms that have worsened as sea levels rise, and provides shelter for innumerable marine creatures. It’s used to make food, fertilizer, medicines, bioplastics, biofuel and animal feed.

(I’m sure that many readers have tried the seaweed salad in ethnic Asian restaurants.)

And now researchers are investigating its use as a source of minerals, such as platinum and rhodium, as well as “rare-earth” elements (which actually aren’t that rare), that are crucial in the renewable-energy sector and in other technological applications, too. Seaweed sucks up these minerals.

Much more research needs to be done to demonstrate all possible uses of seaweed, but the potential for seaweed aquaculture seems enormous. I can see many profitable new seaweed farms being developed off the southern New England coast. There’s already a large kelp-farming sector in the Gulf of Maine, benefiting from the size of available waters, and the industry is growing along the Rhode Island and Connecticut shoreline, too.

It’s heartening to see scientists working on all-natural ways to address global warming. Of course, in some places there will be fights over which sites to take over for seaweed farming; I hope that the broad public interest will usually win over, say, the demands of summer yachtsmen. Certainly, these farm sites should be chosen carefully, with guidance from the likes of the Marine Biological Laboratory, in the village of Woods Hole in Falmouth, Mass.

Hit these links and this one (video).