Llewellyn King: New graduates should learn how to manage rejection

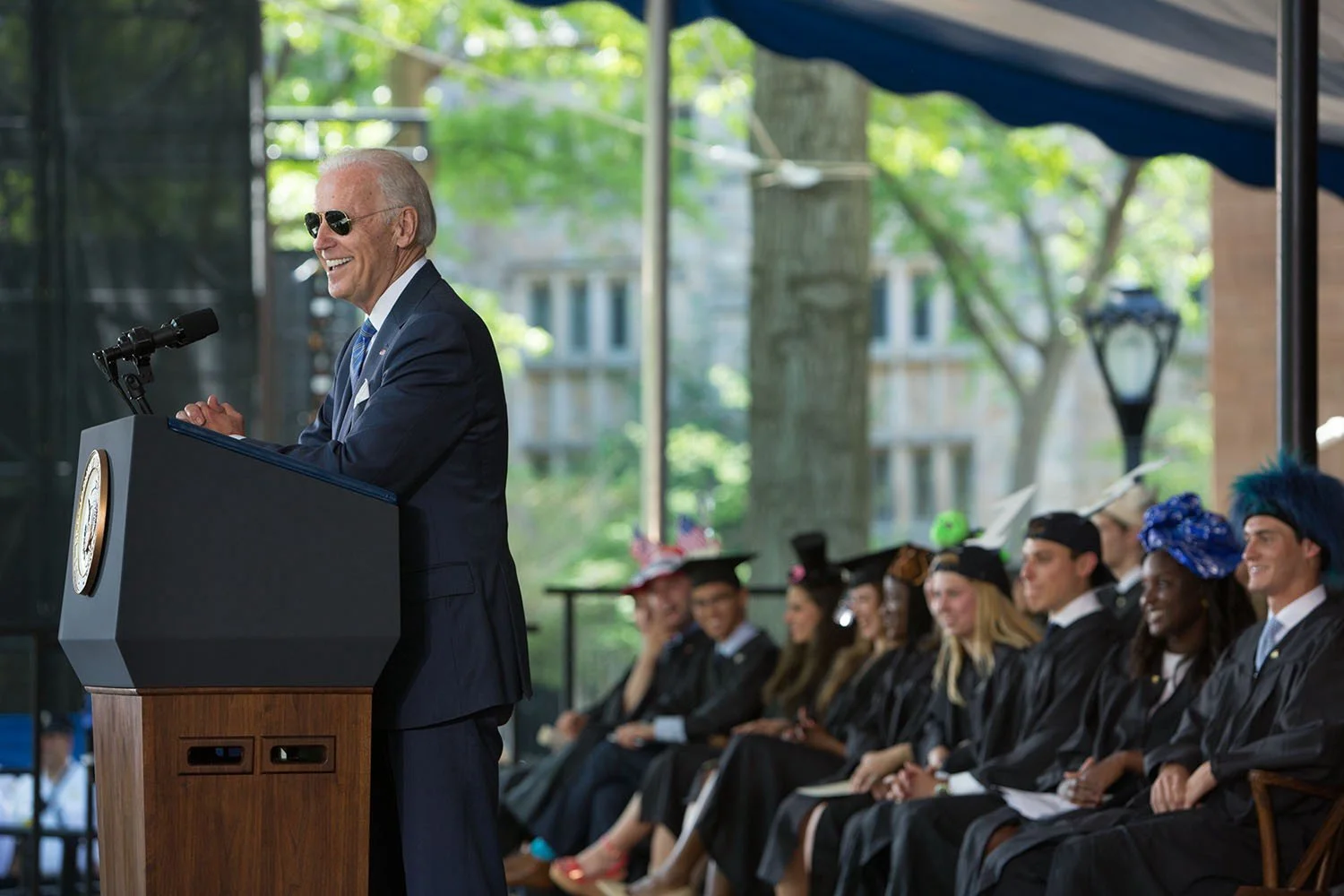

Then-Vice President Biden giving commencement speech at Yale University in 2015.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

As so many commencement addresses aren’t being delivered this year, I thought I would share what I would have said to graduates if I had been invited by a college or university to be a speaker.

“The first thing to know is that you are graduating at a propitious time in human history — for example, think of how artificial intelligence is enabling medical breakthroughs.

“A vast world of possibilities awaits you because you are lucky enough to be living in a liberal democracy. It happens to be America, but the same could be true of any of the democratic countries.

“Look at the world, and you will see that the countries with democracy are also prosperous places where individuals can follow their passion. Doubly or triply so in America.

“Despite all the disputes, unfairness and politics, the United States is foremost among places to live and work — where the future is especially tempting. I say this having lived and worked on three continents and traveled to more than 180 countries. Just think of the tens of millions who would live here if they could.

“In a society that is politically and commercially free, as it is in the United States, the limits we encounter are the limits we place on ourselves.

“That is what I want to tell you: Don’t fence yourself in.

“But do work always to keep that freedom, your freedom, especially now.

“Seldom mentioned, but the greatest perverters of careers, stunters of ambition and all-around enfeeblers you will contend with aren’t the government, a foreign power, shortages or market conditions, but how you manage rejection.

“Fear of rejection is, I believe, the great inhibitor. It shapes lives, hinders careers and is ever-present, from young love to scientific creation.

“The creative is always vulnerable to the forces of no, to rejection.

“No matter what you do, at some point you will face rejection — in love, in business, in work or in your own family.

“But if you want to break out of the pack and leave a mark, you must face rejection over and over again.

“Those in the fine and performing arts and writers know rejection; it is an expected but nonetheless painful part of the tradition of their craft. If you plan to be an artist of some sort or a writer, prepare to face the dragon of rejection and fight it all the days of your career.

“All other creative people face rejection. Architects, engineers and scientists face it frequently. Many great entrepreneurial ideas have faced early rejection and near defeat.

“If you want to do something better, differently or disruptively, you will face rejection.

“To deal with this world where so many are ready to say no, you must know who you are. Remember that: Know who you are.

“But you can’t know who you are until you have found out who you are.

“Your view of yourself may change over time, but I adjure you always to judge yourself by your bests, your zeniths. That is who you are. Make past success your default setting in assessing your worth when you go forth to slay the dragons of rejection.

“There are two classes of people you will encounter again and again in your lives. The yes people and the no people.

“Seek out and cherish those who say yes. Anyone can say no. The people who have changed the world, who have made it a better place, are the people who have said, ‘Yes.’ ‘Why not?’ ‘Let’s try.’

“Those are people you need in life, and that is what you should aim to be: a yes person. Think of it historically: Thomas Edison, Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt and Steve Jobs were all yes people, undaunted by frequent rejection.

“Try to be open to ideas, to different voices and to contrarian voices. That way, you will not only prosper in what you seek to do, but you will also become someone who, in turn, will help others succeed.

“You enter a world of great opportunities in the arts, sciences and technology but with attendant challenges. The obvious ones are climate, injustice, war and peace.

“Think of yourselves as engineers, working around those who reject you, building for others, and having a lot of fun doing it.

“Avoid being a no person. No is neither a building block for you nor for those who may look to you. Good luck!”

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island.

White House Chronicle

‘Too much my own’

A mayfly

.

“Watching those lifelong dancers of a day

As night closed in, I felt myself alone

In a life too much my own.…’’

— From “Mayflies,’’ by Richard Wilbur (1921-2017), mostly Massachusetts-based poet

The beauty of work

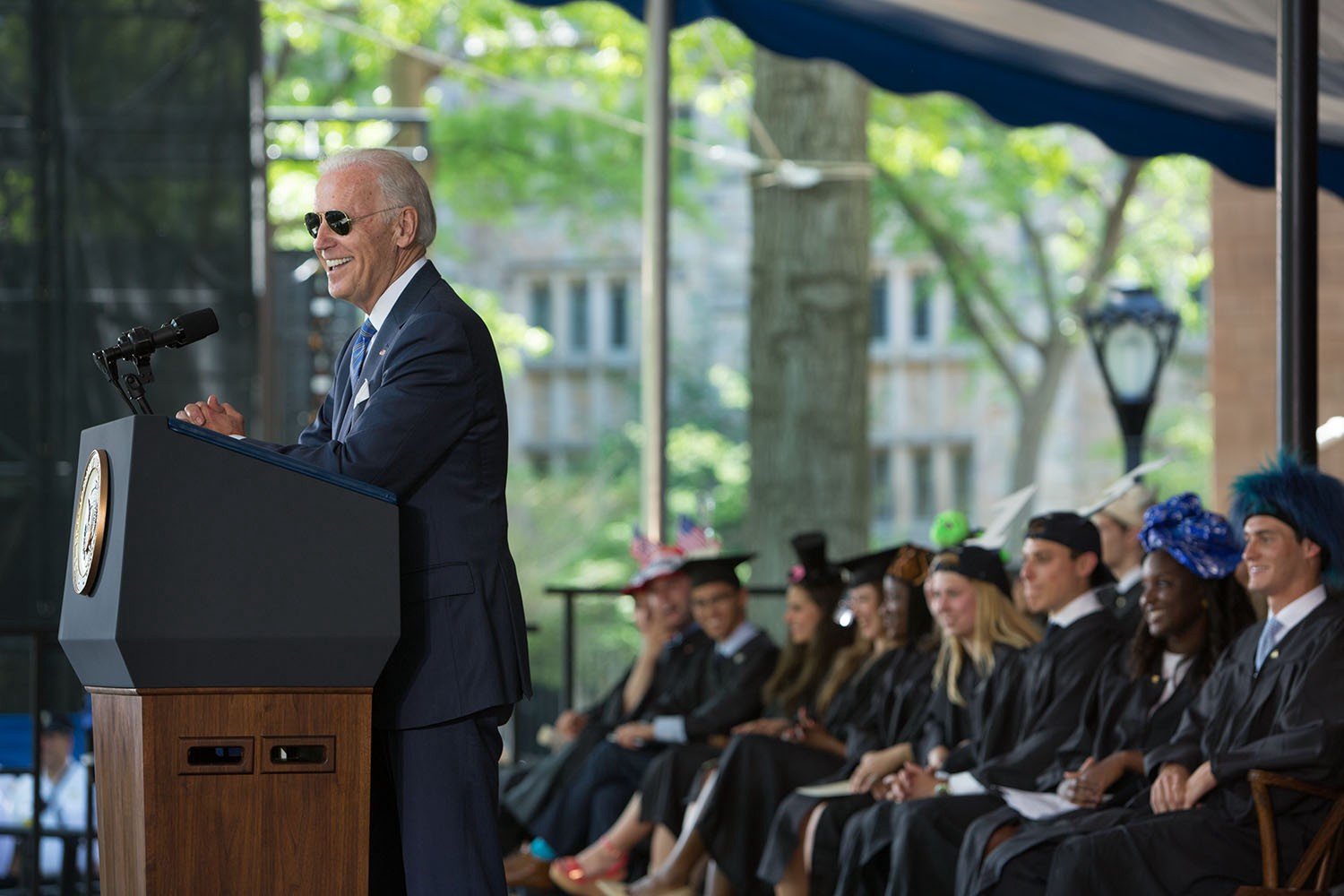

“Rigger's Shop, Provincetown,’’ (oil on canvas), by Childe Hassam (1859-1902), in the show “Impressionist New England: Four Seasons of Color and Light,’’ through Oct. 20, at Heritage Museums and Gardens, Sandwich, Mass.

This is from the collection of New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Lawrence Pond

Dictator of the social climbers

Newport picnic supervised by Ward McAllister.

"Snobbish Society's Schoolmaster” —Caricature of Ward McAllister as an ass telling Uncle Sam he must imitate "an English snob of the 19th Century" or he "will nevah be a gentleman".

Text excerpted from a New England Historical Society article by Emily Parrow

“In Gilded Age Newport, Rhode Island, an invitation to one of Ward McAllister’s summer picnics could make or break a hopeful social climber.

“One contemporary aptly described this era as ‘an ever-shifting kaleidoscope of dazzling wealth, restless endeavor, and rivalry.’ American ideas about class were changing, especially in cities. Old and new money mixed like oil and water. The increase in American fortunes necessitated stricter guidelines for social acceptance. Enter McAllister, a controversial figure who coached this evolving class of insecure millionaires in Old World aristocratic customs.’’

Troubling origin stories

“The invisible enemy should not exist – Seated Nude Male Figure, Wearing Belt Around Waist” (Middle Eastern packaging, newspapers, glue and cardboard), by Iraqi-American artist Michael Rakowitz, in the show “Never Spoken Again: Rogue Stories of Science and Collections,’’ at the Fleming Museum of Art, at University of Vermont, Burlington, through May 18.

— Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Wien Gallery.

The museum says the show is a traveling exhibition that reflects on “the birth of modern collections, the art institutions that sustain them, and their contingent origin stories to reveal a universe of erasures, violence, and fortuity. Considering how institutional collections organize our lives, “Never Spoken Again” brings together artists whose works open up a critique of material culture, iconography and political ecologies.

“In turn, each of the works sheds light on myths, simulations, fake currencies, war games, and the slow violence of systematic racism that historically underpin collecting practices. Together, they invite inquiry into how our collective histories are presented, curated, fabricated, or all of the above. With wit, curiosity, and compassion, “Never Spoken Again” asks the question most museum visitors dare not: How did these objects and artworks get to a gallery in Vermont anyway? And why?

Burlington's Union Station was built in 1916 by the Central Vermont Railway and the Rutland Railroad.

‘Metaphor for living’

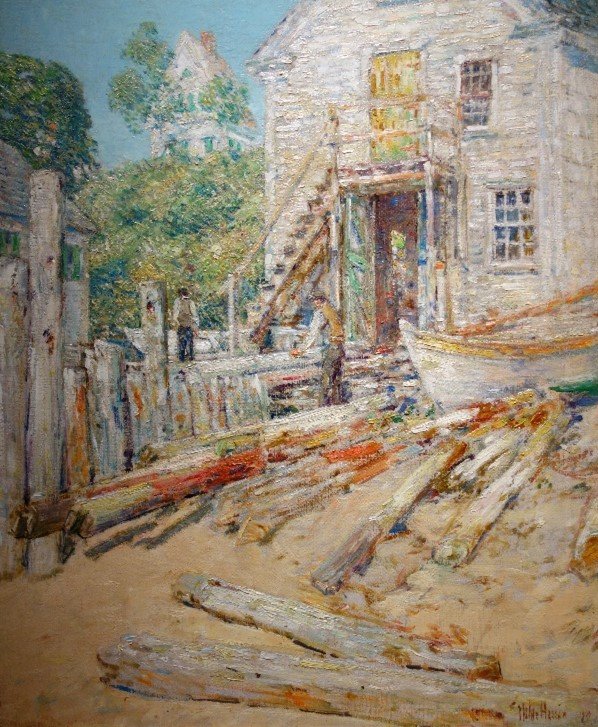

“Dropkick into Primordial Soup” (mixed media), by Cambridge, Mass.-based artist Alexandra Sheldon, in her show “Piece by Piece,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through June 2.

She says:

“Collage is a process of piecing together papers. When I began with the collages in this show, I gathered painted papers for a background. Then I would hunt for shapes to go into the backgrounds. Often the work got too busy, and then I’d try to simplify it by reintroducing backgrounds. This led to shifting surfaces and a back and forth feel which felt good to me.

“Collage is, for me, a metaphor for living. It is difficult to live: to figure out how to balance work with family with body with money with time with everything. In the studio I am searching for combinations of energies. I want to fit in movement, color, shape, line, texture, light, feel, everything. I want suspense, sorrow, enthusiasm, inertia, joy, fear, exploration, everything.

“If in real life I can hardly figure out how to live, at least in the studio I can attempt to jam in everything and explore everything. This is how I find myself: by spending long hours in the studio listening to music and trying to put papers together. Collage leads me and frustrates me, entices me and overjoys me.’’

“And in the end, perhaps it’s those fleeting moments of fun and play in the studio which I love most. Just like in my life.’’

Chris Powell: Don't leave looted Conn. hospitals' fate to a big game of chicken

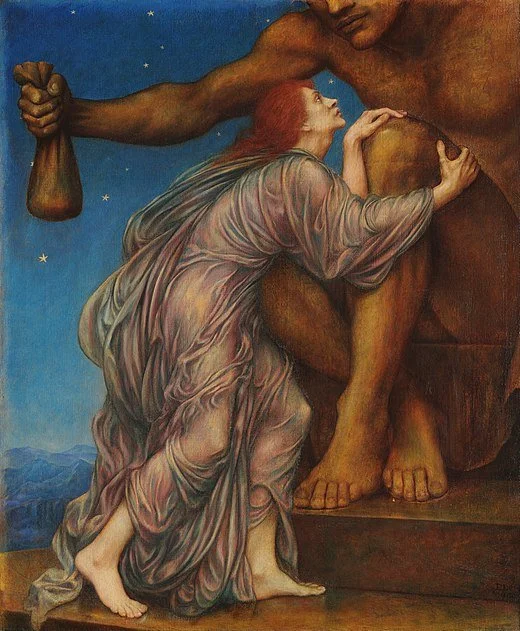

“The Worship of Mammon,’’ by Evelyn De Morgan (1909).

MANCHESTER, Conn.

A big game of chicken may determine what becomes of Waterbury (Conn.) Hospital, Manchester (Conn.) Memorial Hospital, and Rockville General Hospital, in Vernon, Conn.

Yale New Haven Health, which two years ago agreed to buy the three struggling hospitals from Prospect Medical Holdings for $435 million, now is suing Prospect to nullify the agreement. Yale New Haven Health contends that Prospect has substantially impaired the hospitals by mismanagement since the agreement was made.

Prospect's Connecticut hospitals were already in terrible financial condition, most of their equity having been stripped from them and liquidated by their parent company, Leonard Green and Partners, a private-equity investment firm based in California. The Prospect hospitals no longer own their own real estate but must pay rent to a real-estate company.

Connecticut law never should have allowed nonprofit hospitals, which Waterbury, Manchester and Rockville were, to be acquired by investment companies like Prospect. The state now has a big interest in keeping the hospitals operating, restoring their solvency, and returning them to nonprofit status.

But Yale New Haven Health has a big interest in not overpaying for an operation that may be on the verge of collapse and bankruptcy. After all, Yale New Haven Health runs four hospitals in Connecticut, all nonprofits, and they could be critically weakened if their parent company pays too much for the Prospect hospitals.

As the condition of the Prospect hospitals deteriorated after Yale New Haven Health agreed to acquire them, Yale New Haven Health asked state government to subsidize its purchase by $80 million. Gov. Ned Lamont didn't want to do that and urged the two sides to keep negotiating. But with the acquisition unfulfilled after two years and the lawsuit charging bad faith, negotiations have failed and seem unlikely to resume soon. The Prospect hospitals are far behind in paying bills and state and municipal taxes. They may not have any net worth left at all.

But the Prospect hospitals serve large communities and their closure would be a disaster for Connecticut. Other hospitals are not prepared to take up the displaced patient load, and even if they could handle it, many patients of the failing hospitals and the doctors who treat them would have far to travel. The disruption to medical care in the state would be immense. Despite Prospect's awful ownership and top management, its hospitals employ hundreds of dedicated professionals striving to provide excellent care under worsening financial stress.

State government's financial intervention in support of an acquisition by Yale New Haven Health strikes many as the obvious solution.

But a state subsidy for the purchase will ratify Prospect's looting of its three hospitals and the real-estate company's purchase of the hospitals' property. The real-estate company now may think it has decisive leverage over whoever acquires the hospitals and intends to keep them operating. But if the hospitals fail and go out of business, their buildings probably would lose much of their value, since they have practical use only as hospitals.

The best mechanism for saving the hospitals may be to let them fail and go into bankruptcy. Bankruptcy is exclusively a federal court process but with the court's approval state government could become a party to the case and assist the financial reorganization of the hospitals from the moment of their bankruptcy filing. Bankruptcy could relieve the hospitals of their burdensome property rental obligations.

In any case state government should do more than what it long has been doing about this problem -- just hoping that Yale New Haven Health and Prospect will work things out eventually before the Prospect hospitals collapse and close. Hope is not a strategy or plan.

So the governor should assemble a team ready to assist a bankruptcy proceeding, the General Assembly should make millions of dollars in an emergency loan available to a new owner of the hospitals, and the legislature and governor should give Connecticut a law to prevent nonprofit hospitals from falling into the hands of predators ever again, and thus to prevent the theft of decades of community charity that state government's negligence allowed here.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Augmented reality in Medfield

“Agent 57’’ (detail from Alpha augmented reality), by Michael Lewy, in the group show “Augmented Reality — The evolution of a small town,’’ at the Zullo Gallery Center for the Arts, Medfield, Mass., May 11-June 23.

The gallery says the show’s works focus on the past, present and future of the town of Medfield, which was once best known for its big state mental hospital.

The Boston origins of Mother’s Day

Julia Ward Howe

Text excerpted from The Boston Guardian

(Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

Mother’s Day got its start on Beacon Street in Boston’s Back Bay celebrating not only mothers but peace.

Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910), who lived most of her life at 241 Beacon Street, began advocating a “Mother’s Day” in the 1870s.

The ancient Greeks held spring ceremonies for Rhea, mother of gods, and in the 1600s the English had a “Mothering Day”, where servants were given the fourth Sunday of Lent off to bring cakes to their mothers.

America’s Mother’s Day, however, started with Howe.

Howe was not an average mother.

She was an activist, an abolitionist, a women’s suffrage advocate and a writer who clashed with her prominent transcendentalist husband Samuel Gridley Howe over his wish that she shun public life. According to her diary, he beat her. She considered divorcing him on various occasions but never did.

1915 Mother’s Day card. Of course, some may have more nuanced views of their mothers.

Christopher Niezrecki: What has hurt the offshore wind industry, and what to do about it

The five-turbine wind farm off Block Island

LOWELL, Mass.

America’s first large-scale offshore wind farms began sending power to the Northeast in early 2024, but a wave of wind farm project cancellations and rising costs have left many people with doubts about the industry’s future in the U.S.

Several big hitters, including Ørsted, Equinor, BP and Avangrid, have canceled contracts or sought to renegotiate them in recent months. Pulling out meant the companies faced cancellation penalties ranging from US$16 million to several hundred million dollars per project. It also resulted in Siemens Energy, the world’s largest maker of offshore wind turbines, anticipating financial losses in 2024 of around $2.2 billion.

Altogether, projects that had been canceled by the end of 2023 were expected to total more than 12 gigawatts of power, representing more than half of the capacity in the project pipeline.

So, what happened, and can the U.S. offshore wind industry recover?

Estimates of the mean annual wind speeds in meters per second extending 200 kilometers from shore at a height of 330 feet (100 meters). ESMAP/The World Bank via Wikimedia, CC BY

I lead UMass Lowell’s Center for Wind Energy Science Technology and Research WindSTAR and Center for Energy Innovation and follow the industry closely. The offshore wind industry’s troubles are complicated, but it’s far from dead in the U.S., and some policy changes may help it find firmer footing.

Long approval process’s cascade of challenges

Getting offshore wind projects permitted and approved in the U.S. takes years and is fraught with uncertainty for developers, more so than in Europe or Asia.

Before a company bids on a U.S. project, the developer must plan the procurement of the entire wind farm, including making reservations to purchase components such as turbines and cables, construction equipment and ships. The bid must also be cost-competitive, so companies have a tendency to bid low and not anticipate unexpected costs, which adds to financial uncertainty and risk.

The winning U.S. bidder then purchases an expensive ocean lease, costing in the hundreds of millions of dollars. But it has no right to build a wind project yet.

Continental shelf areas leased for wind power development along the Atlantic coast. U.S. Department of the Interior, 2024

Before starting to build, the developer must conduct site assessments to determine what kind of foundations are possible and identify the scale of the project. The developer must consummate an agreement to sell the power it produces, identify a point of interconnection to the power grid, and then prepare a construction and operation plan, which is subject to further environmental review. All of that takes about five years, and it’s only the beginning.

For a project to move forward, developers may need to secure dozens of permits from local, tribal, state, regional and federal agencies. The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which has jurisdiction over leasing and management of the seabed, must consult with agencies that have regulatory responsibilities over different aspects in the ocean, such as the armed forces, Environmental Protection Agency and National Marine Fisheries Service, as well as groups including commercial and recreational fishing, Indigenous groups, shipping, harbor managers and property owners.

For Vineyard Wind I – which began sending power from five of its 62 planned wind turbines off Martha’s Vineyard in early 2024 – the time from BOEM’s lease auction to getting its first electricity to the grid was about nine years.

Costs can balloon during the regulatory delays

Until recently, these contracts didn’t include any mechanisms to adjust for rising supply costs during the long approval time, adding to the risk for developers.

From the time today’s projects were bid to the time they were approved for construction, the world dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, global supply chain problems, increased financing costs and the war in Ukraine. Steep increases in commodity prices, including for steel and copper, as well as in construction and operating costs, made many contracts signed years earlier no longer financially viable.

New and re-bid contracts are now allowing for price adjustments after the environmental approvals have been given, which is making projects more attractive to developers in the U.S. Many of the companies that canceled projects are now rebidding.

The regulatory process is becoming more streamlined, but it still takes about six years, while other countries are building projects at a faster pace and larger scale.

Shipping rules, power connections

Another significant hurdle for offshore wind development in the U.S. involves a century-old law known as the Jones Act.

The Jones Act requires vessels carrying cargo between U.S. points to be U.S.-built, U.S.-operated and U.S.-owned. It was written to boost the shipping industry after World War I. However, there are only three offshore wind turbine installation vessels in the world that are large enough for the turbines proposed for U.S. projects, and none are compliant with the Jones Act.

That means wind turbine components must be transported by smaller barges from U.S. ports and then installed by a foreign installation vessel waiting offshore, which raises the cost and likelihood of delays.

A generator and blades head for the South Fork Wind farm from New London, Conn., on Dec. 4, 2023. AP Photo/Seth Wenig

Dominion Energy is building a new ship, the Charybdis, that will comply with the Jones Act. But a typical offshore wind farm needs over 25 different types of vessels – for crew transfers, surveying, environmental monitoring, cable-laying, heavy lifting and many other roles.

The nation also lacks a well-trained workforce for manufacturing, construction and operation of offshore wind farms.

For power to flow from offshore wind farms, the electricity grid also requires significant upgrades. The Department of Energy is working on regional transmission plans, but permitting will undoubtedly be slow.

Lawsuits, disinformation add to the challenges

Numerous lawsuits from advocacy groups that oppose offshore wind projects have further slowed development.

Wealthy homeowners have tried to stop wind farms that might appear in their ocean view. Astroturfing groups that claim to be advocates of the environment, but are actually supported by fossil fuel industry interests, have launched disinformation campaigns.

In 2023, many Republican politicians and conservative groups immediately cast blame for whale deaths off the coast of New York and New Jersey on the offshore wind developers, but the evidence points instead to increased ship traffic collisions and entanglements with fishing gear.

Such disinformation can reduce public support and slow projects’ progress.

Efforts to keep the offshore wind industry going

The Biden administration set a goal to install 30 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030, but recent estimates indicate that the actual number will be closer to half that.

Passengers on a boat view America’s first offshore wind farm, owned by the Danish company Ørsted. Its five turbines generate power off Block Island, R.I. AP Photo/David Goldman

Despite the challenges, developers have reason to move ahead.

The Inflation Reduction Act provides incentives, including federal tax credits for the development of clean energy projects and for developers that build port facilities in locations that previously relied on fossil fuel industries. Most coastal state governments are also facilitating projects by allowing for a price readjustment after environmental approvals have been given. They view offshore wind as an opportunity for economic growth.

These financial benefits can make building an offshore wind industry more attractive to companies that need market stability and a pipeline of projects to help lower costs – projects that can create jobs and boost economic growth and a cleaner environment.

Christopher Niezrecki is director of the Center for Energy Innovation at the Center for Energy Innovation at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell.

Mr. Niezrecki is director of UMass Lowell’s Industry-University Cooperative Research Center for Wind Energy Science Technology and Research (WindSTAR), which receives funding from the National Science Foundation and several energy-related companies.

Five years wide awake

"Once in everyone's life there is apt to be a period when he is fully awake, instead of half asleep. I think of those five years in Maine as the time when this happened to me ... I was suddenly seeing, feeling, and listening as a child sees, feels, and listens. It was one of those rare interludes that can never be repeated, a time of enchantment. I am fortunate indeed to have had the chance to get some of it down on paper."

From One Man’s Meat, E.B. White’s collection of essays written for Harper’s Magazine, in a foreword written 40 years after its initial publication, in 1942. He moved to a “salt-water farm’’ in Brooklin, Maine, in 1938 from New York City (where he frequently returned to work at The New Yorker in stints). The farm most famously inspired the classic children’s (and adults’) book Charlotte’s Web.

Using 3D printing in building neighborhoods

Home built using University of Maine 3D printer and wood.

Edited from a New England Council report

“The University of Maine has created a 3D printer that could be used to build a house, cutting construction times and costs. Now, it is one of the largest in the world and could be capable of being used to build entire neighborhoods. The recently publicized printer is four times the size of the original one, commissioned less than five years ago, and can use bio-based materials (such as wood from Maine’s big forestry sector) to address affordable-housing issues as well.

“This new massive printer ‘opens up new research frontiers to integrate these collaborative robotics operations at a very large scale with new sensors, high-performance computing, and artificial intelligence,’ said Habib Dagher, director of the university’s Advanced Structures & Composite Center, at the university’s flagship campus, in Orono, where UMaine houses its printers.

Get out the insulin

“Ice Cream Sandwich”, by Connecicut artist Peter Anton, at the Fairfield (Conn.) University Art Museum, May 10-July 27.

The gallery says:

“Anton's work, made of wood, metal, plastic resin, oil and acrylic paints, encourages "people to think about their own relationship to food, and the memories and nostalgia that these childhood favorites conjure."

Llewellyn King: The trials of celebrity love, from Taylor-Burton to Swift-Kelce

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra (1963)

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I wouldn’t know Taylor Swift if she sat next to me on an airplane, which is unlikely because she travels by private jet. If she were to take a commercial flight, she wouldn’t be sitting in the economy seats, which the airlines politely call coach.

Swift (who lives in Watch Hill, R.I., part of the time) needs to go by private jet these days: She is dating Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce, and that is a problem. Love needs candle-lightin,g not floodlighting.

Being in love when you are famous, especially if both the lovers are famous, is tough. The normal, simple joys of that happy state are a problem: There is no privacy, precious few places outside of gated homes where the lovers can be themselves.

They can’t do any of the things unfamous lovers take for granted, like catching a movie, holding hands or stealing a kiss in public without it being caught on video and transmitted on social media to billions of fans. Dinner for two in a cozy restaurant and what each orders is flashed around the world. “Oysters for you, sir?”

Worse, if the lovers are caught in public not doing any of those things and, say, staring into the middle distance looking glum, the same social media will erupt with speculation about the end of the affair.

If you are a single celebrity, you are gossip-bait, catnip for the paparazzi. If a couple, the speculation is whether it will be wedding bells or splitsville.

The world at large is convinced that celebrity lovers are somehow in a different place from the rest of us. It isn’t true, of course, but there we are: We think their highs are higher and lows are lower.

That is doubtful, but it is why we yearn to hear about the ups and downs of their romances; Swift’s more than most because they are the raw material of her lyrics. Break up with Swift and wait for the album.

When I was a young reporter in London in the 1960s, I did my share of celebrity chasing. Mostly, I found, the hunters were encouraged by their prey. But not when Cupid was afoot. Celebrity is narcotic except when the addiction is inconvenient because of a significant other.

In those days, the most famous woman in the world, and seen as the most beautiful, was Elizabeth Taylor. I was employed by a London newspaper to follow her and her lover, Richard Burton, around London. They were engaged in what was then, and maybe still is, the most famous love affair in the world.

The great beauty and the great Shakespearian actor were the stuff of legends. It also was a scandal because when they met in Rome, on the set of Cleopatra, they were both married to other people. She to the singer Eddie Fisher and he to his first wife, the Welsh actress and theater director Sybil Williams.

Social rules were tighter then and scandal had a real impact. This scandal, like most scandals of a sexual nature, raised consternation along with prurient curiosity.

My role at The Daily Sketch was to stake out the lovers where they were staying at the luxury Dorchester Hotel, on Park Lane.

I never saw Taylor and Burton. Day after day I would be sidetracked by the hotel’s public-relations officer with champagne and tidbits of gossip, while they escaped by a back entrance.

Then, one Sunday in East Dulwich, a leafy part of South London where I lived with my first wife, Doreen, one of the great London newspaper writers, I happened upon them.

Every Sunday, we went to the local pub for lunch, which included traditional English roast beef or lamb. It was a good pub — which today might be called a gastropub, but back then it was just a pub with a dining room. An enticing place.

One Sunday, we went as usual to the pub and were seated right next to my targets: the most famous lovers in the world, Taylor and Burton. The elusive lovers, the scandalous stars were there next to me: a gift to a celebrity reporter.

I had never seen before, nor in the many years since, two people so in love, so aglow, so entranced with each other, so oblivious to the rest of the room. No movie that they were to star in ever captured love as palpable as the aura that enwrapped Taylor and Burton. You could warm your hands on it. Doreen whispered from behind her hand, “Are you going to call the office?”

I looked at the lovers and shook my head. They were so happy, so beautiful, so in love I didn’t have the heart to break the spell.

I wasn’t sorry I didn’t call in a story then and I haven’t changed my mind.

Love in a gilded cage is tough. If Swift and Kelce are at the next table — unlikely -- in a restaurant, I will keep mum. Love conquers all.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Web site: whchronicle.co

‘Dreamscapes’

‘Reader” (oil on linen), by Anthony Cudahy, in his show ‘‘Spinneret,’’ at the Ogunquit (Maine) Museum of American Art,

— Photograph by JSP Art Photography

Eric J. Taubert writes of the show:

"Step inside the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, and a luminous transformation unfolds. The salt-spray roar of the Gulf of Maine retreats and a different type of sensory gale rises up. Phosphorescent dreamscapes. Intoxicating light and shadows. Hues so delicious you can almost taste them. Familiar faces you couldn’t possibly know. This is 'Spinneret,' the first solo exhibition in the United States by the contemporary figurative painter Anthony Cudahy.’’

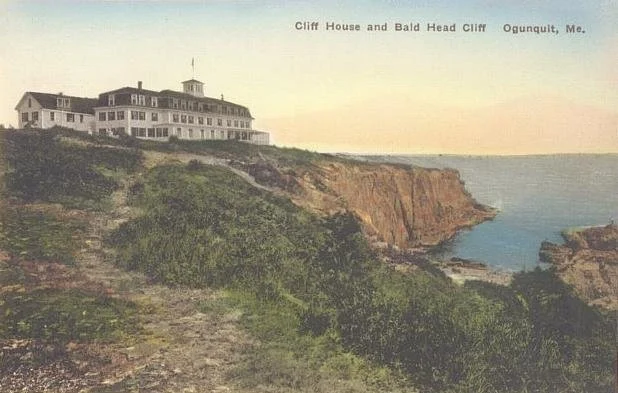

The Cliff House in Ogunquit in 1920

‘Mass timber’ building

Mixed coniferous and deciduous forest in Presque Isle, Maine.

—Photo by Itsasatire

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Most of New England is woodland, especially, of course, Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. Well-managed forests can be an economic boon, especially given the renewability of wood as a building material. (Let’s hope that a hurricane doesn’t blow down a lot of it, which is what happened in 1938.)

I thought of this after reading Abigail Brone’s article on the New England News Collaborative website about the use of “mass timber,’’ which involves installing wood panels in place of concrete and steel, whose manufacturing emits a great deal of carbon dioxide. The wood panels are shipped to building sites from fabrication centers elsewhere. Installing wood cuts labor costs compared to handling concrete and steel. This, among other things, could encourage a speedup in much-needed housing construction over the next few years.

Ms. Brone notes that the cost of mass timber in New England is substantially raised by having to be shipped from the South and Canada. But why not harvest a lot of New England wood for the purpose – especially from Maine, which is almost 90 percent forested?

A University of Maine report says:

“The Maine Mass Timber Commercialization Center (MMTCC) brings together industrial partners, trade organizations, construction firms, architects, and other stakeholders in the region to revitalize and diversify Maine’s forest-based economy by bringing innovative mass timber manufacturing to the State of Maine. The emergence of this new innovation-based industry cluster will result in positive economic impacts to both local and regional economies, particularly in Maine’s rural communities.”

Martha Bebinger: Switching to eco-friendly inhalers

Three types of dry powder inhalers: Turbuhaler, Accuhaler and Ellipta devices.

Via Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

Miguel Divo, a lung specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston, sits in an exam room across from Joel Rubinstein, who has asthma. Rubinstein, a retired psychiatrist, is about to get a checkup and hear a surprising pitch — for the planet, as well as his health.

Divo explains that boot-shaped inhalers, which represent nearly 90% of the U.S. market for asthma medication, save lives but also contribute to climate change. Each puff from an inhaler releases a hydrofluorocarbon gas that is 1,430 to 3,000 times as powerful as the most commonly known greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide.

“That absolutely never occurred to me,” said Rubinstein. “Especially, I mean, these are little, teeny things.”

So Divo has begun offering a more eco-friendly option to some patients with asthma and other lung diseases: a plastic, gray cylinder about the size and shape of a hockey puck that contains powdered medicine. Patients suck the powder into their lungs — no puff of gas required and no greenhouse gas emissions.

“You have the same medications, two different delivery systems,” Divo said.

Patients in the United States are prescribed roughly 144 million of what doctors call metered-dose inhalers each year, according to the most recently available data published in 2020. The cumulative amount of gas released is the equivalent of driving half a million gas-powered cars for a year. So, the benefits of moving to dry powder inhalers from gas inhalers could add up.

Hydrofluorocarbon gas contributes to climate change, which is creating more wildfire smoke, other types of air pollution, and longer allergy seasons. These conditions can make breathing more difficult — especially for people with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD — and increase the use of inhalers.

Divo is one of a small but growing number of U.S. physicians determined to reverse what they see as an unhealthy cycle.

“There is only one planet and one human race,” Divo said. “We are creating our own problems and we need to do something.”

So Divo is working with patients like Rubinstein who may be willing to switch to dry-powder inhalers. Rubinstein said no to the idea at first because the powder inhaler would have been more expensive. Then his insurer increased the co-pay on the metered-dose inhaler so Rubinstein decided to try the dry powder.

“For me, price is a big thing,” said Rubinstein, who has tracked health-care and pharmaceutical spending in his professional roles for years. Inhaling the medicine using more of his own lung power was an adjustment. “The powder is a very strange thing, to blow powder into your mouth and lungs.”

But for Rubinstein, the new inhaler works and his asthma is under control. A recent study found that some patients in the United Kingdom who use dry- powder inhalers have better asthma control while reducing greenhouse-gas emissions. In Sweden, where the vast majority of patients use dry powder inhalers, rates of severe asthma are lower than in the United States.

Rubinstein is one of a small number of U.S. patients who have made the transition. Divo said that, for a variety of reasons, only about a quarter of his patients even consider switching. Dry-powder inhalers are often more expensive than gas-propellant inhalers. For some, dry powder isn’t a good option because not all asthma or COPD sufferers can get their medications in this form. And dry powder inhalers aren’t recommended for young children or elderly patients with diminished lung strength.

Also, some patients using dry powder inhalers worry that without the noise from the spray, they may not be receiving the proper dose. Other patients don’t like the taste that powder inhalers can leave in their mouths.

Divo said his priority is making sure patients have an inhaler they are comfortable using and that they can afford. But, when appropriate, he’ll keep offering the dry powder option.

Advocacy groups for asthma and COPD patients support more conversations about the connection between inhalers and climate change.

“The climate crisis makes these individuals have a higher risk of exacerbation and worsening disease,” said Albert Rizzo, chief medical officer of the American Lung Association. “We don’t want medications to contribute to that.”

Rizzo said there is work being done to make metered-dose inhalers more climate-friendly. The United States and many other countries are phasing down the use of hydrofluorocarbons, which are also used in refrigerators and air conditioners. It’s part of the global attempt to avoid the worst possible impacts of climate change. But inhaler manufacturers are largely exempt from those requirements and can continue to use the gases while they explore new options.

Some leading inhaler manufacturers have pledged to produce canisters with less potent greenhouse gases and to submit them for regulatory review by next year. It’s not clear when these inhalers might be available in pharmacies. Separately, the FDA is spending about $6 million on a study about the challenges of developing inhalers with a smaller carbon footprint.

Rizzo and other lung specialists worry these changes will translate into higher prices. That’s what happened in the early to mid-2000s when ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were phased out of inhalers. Manufacturers changed the gas in metered-dose inhalers and the cost to patients nearly doubled. Today, many of those re-engineered inhalers remain expensive.

William Feldman, a pulmonologist and health-policy researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said these dramatic price increases occur because manufacturers register updated inhalers as new products, even though they deliver medications already on the market. The manufacturers are then awarded patents, which prevent the production of competing generic medications for decades. The Federal Trade Commission says it is cracking down on this practice.

After the CFC ban, “manufacturers earned billions of dollars from the inhalers,” Feldman said of the re-engineered inhalers.

When inhaler costs went up, physicians say, patients cut back on puffs and suffered more asthma attacks. Gregg Furie, medical director for climate and sustainability at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, is worried that’s about to happen again.

“While these new propellants are potentially a real positive development, there’s also a significant risk that we’re going to see patients and payers face significant cost hikes,” Furie said.

Some of the largest inhaler manufacturers, including GSK, are already under scrutiny for allegedly inflating prices in the United States. Sydney Dodson-Nease told NPR and KFF Health News that the company has a strong record for keeping medicines accessible to patients but that it’s too early to comment on the price of the more environmentally sensitive inhalers the company is developing.

Developing affordable, effective, and climate-friendly inhalers will be important for hospitals as well as patients. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommends that hospitals looking to shrink their carbon footprint reduce inhaler emissions. Some hospital administrators see switching inhalers as low-hanging fruit on the list of climate-change improvements a hospital might make.

But Brian Chesebro, medical director of environmental stewardship at Providence, a hospital network in Oregon, said, “It’s not as easy as swapping inhalers.”

Chesebro said that even among metered-dose inhalers, the climate impact varies. So pharmacists should suggest the inhalers with the fewest greenhouse gas emissions. Insurers should also adjust reimbursements to favor climate-friendly alternatives, he said, and regulators could consider emissions when reviewing hospital performance.

Samantha Green, a family physician in Toronto, said clinicians can make a big difference with inhaler emissions by starting with the question: Does the patient in front of me really need one?

Green, who works on a project to make inhalers more environmentally sustainable, said that research shows a third of adults diagnosed with asthma may not have the disease.

“So that’s an easy place to start,” Green said. “Make sure the patient prescribed an inhaler is actually benefiting from it.”

Green said educating patients has a measurable effect. In her experience, patients are moved to learn that emissions from the approximately 200 puffs in one inhaler are equivalent to driving about 100 miles in a gas-powered car. Some researchers say switching to dry powder inhalers may be as beneficial for the climate as a patient adopting a vegetarian diet.

One of the hospitals in Green’s health-care network, St. Joseph’s Health Centre, found that talking to patients about inhalers led to a significant decrease in the use of metered-dose devices. Over six months, the hospital went from 70% of patients using the puffers, to 30%.

Green said patients who switched to dry powder inhalers have largely stuck with them and appreciate using a device that is less likely to exacerbate environmental conditions that inflame asthma.

This article is from a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR, and KFF Health News.

Martha Bebinger is a WBUR reporter; marthab@wbur.org, @mbebinger

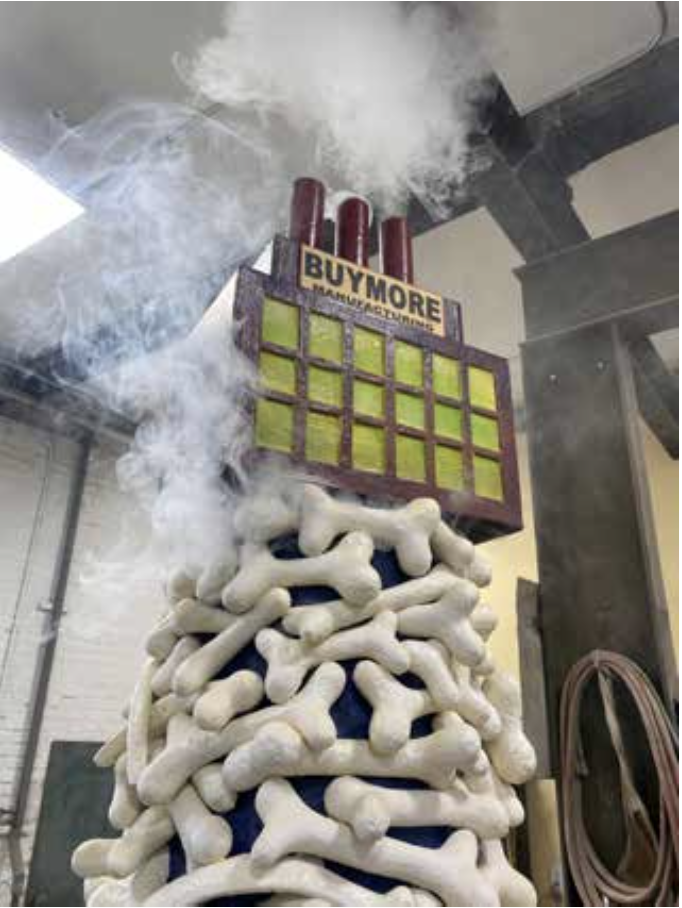

Extinction pile

“Built on the Past’’ (detail) (mixed media sculpture), by George LeMaitre, in his show with Pat Fietta, “Pondering Environmental Anxieties,’’ at Future Lab(s) Gallery, North Adams, Mass., through May 27.

https://www.futurelabsgallery.com/

Looming from the Jazz Age

The Industrial Trust Building, in downtown Providence, now being retrofitted for apartments. Opened in 1928, it’s an Art Deco monument and reminder of the optimism of the “Roaring Twenties.’’

— 2019 Photo by Lydia Whitcomb

‘Byproduct’ of daily life

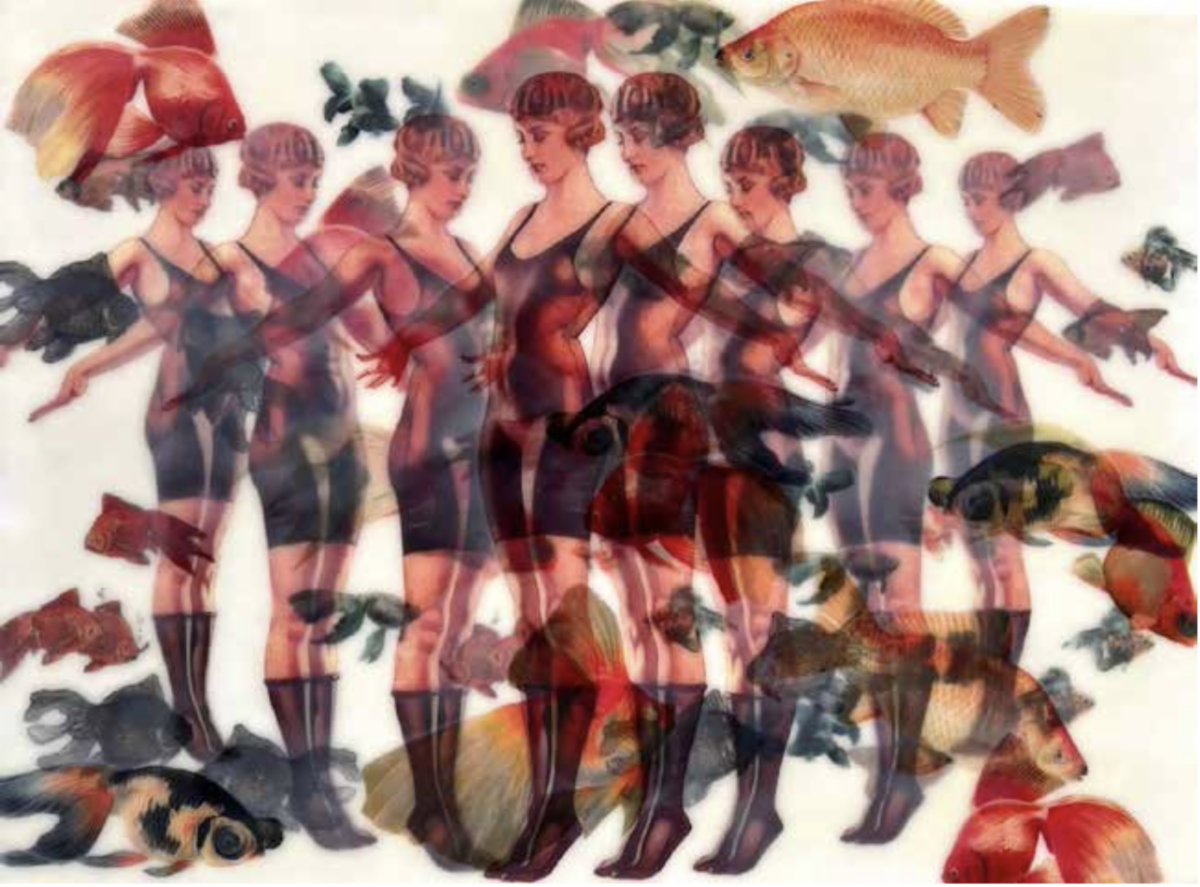

“The Age of Aquarium” (encaustic with layered toner transfers), by Providence-based artist Angel Dean, in New England Wax’s group show “Transparency,’’ at Wellfleet (Mass.) Preservation Hall, May 21-June 27. Also see the 17th Annual International Encaustic Conference in nearby Provincetown, May 31-June 2.

Ms. Dean’s artist statement includes this:

“Angel Dean is an artist who mainly works with encaustic media. Her work is personal and unconventional. By contesting the division between the realm of memory and the realm of experience, Dean makes work that is the by-product of the life she’s living.

“‘The advice I like to give young artists, or really anybody who’ll listen to me, is not to wait around for inspiration. Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up & get to work. If you wait around for the clouds to part & a bolt of lightning to strike you in the brain, you are not going to make an awful lot of work. All the best ideas come out of the process; they come out of the work itself. Things occur to you.”’

— Chuck Close