Erik Bleich and Christopher Star: 'Apocalypse' has become a secular term, too

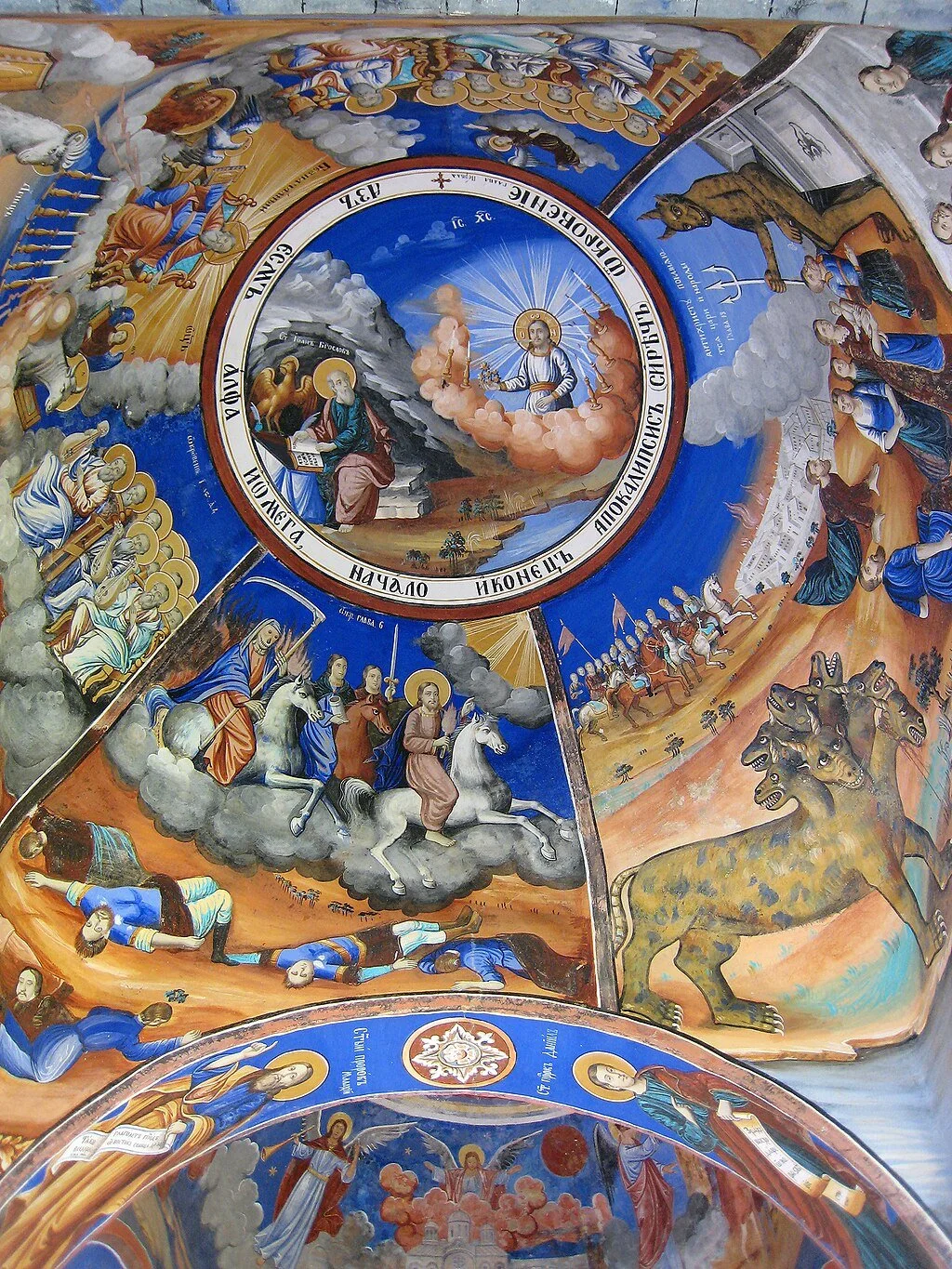

Apocalypse depicted in Christian Orthodox traditional fresco scenes in Osogovo Monastery, North Macedonia

From The Conversation

MIDDLEBURY, VT.

The exponential growth of artificial intelligence over the past year has sparked discussions about whether the era of human domination of our planet is drawing to a close. The most dire predictions claim that the machines will take over within five to 10 years.

Fears of AI are not the only things driving public concern about the end of the world. Climate change and pandemic diseases are also well-known threats. Reporting on these challenges and dubbing them a potential “apocalypse” has become common in the media – so common, in fact, that it might go unnoticed, or may simply be written off as hyperbole.

Is the use of the word “apocalypse” in the media significant? Our common interest in how the American public understands apocalyptic threats brought us together to answer this question. One of us is a scholar of the apocalypse in the ancient world, and the other studies press coverage of contemporary concerns.

By tracing what events the media describe as “apocalyptic,” we can gain insight into our changing fears about potential catastrophes. We have found that discussions of the apocalypse unite the ancient and modern, the religious and secular, and the revelatory and the rational. They show how a term with roots in classical Greece and early Christianity helps us articulate our deepest anxieties today.

What is an apocalypse?

Humans have been fascinated by the demise of the world since ancient times. However, the word apocalypse was not intended to convey this preoccupation. In Greek, the verb “apokalyptein” originally meant simply to uncover, or to reveal.

In his dialogue “Protagoras,” Plato used this term to describe how a doctor may ask a patient to uncover his body for a medical exam. He also used it metaphorically when he asked an interlocutor to reveal his thoughts.

A wood engraving by German painter Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld illustrates a scene from the Book of Revelation. ZU_09/DigitalVision Vectors via Getty images

New Testament authors used the noun “apokalypsis” to refer to the “revelation” of God’s divine plan for the world. In the original Koine Greek version, “apokalypsis” is the first word of the Book of Revelation, which describes not only the impending arrival of a painful inferno for sinners, but also a second coming of Christ that will bring eternal salvation for the faithful.

The apocalypse in the contemporary world

Many American Christians today feel that the day of God’s judgment is just around the corner. In a December 2022 Pew Research Center Survey, 39% of those polled believed they were “living in the end times,” while 10% said that Jesus will “definitely” or “probably” return in their lifetime.

Yet for some believers, the Christian apocalypse is not viewed entirely negatively. Rather, it is a moment that will elevate the righteous and cleanse the world of sinners.

Secular understandings of the word, by contrast, rarely include this redeeming element. An apocalypse is more commonly understood as a cataclysmic, catastrophic event that will irreparably alter our world for the worse. It is something to avoid, not something to await.

What we fear most, decade by decade

Political communications scholars Christopher Wlezien and Stuart Soroka demonstrate in their research that the media are likely to reflect public opinion even more than they direct it or alter it. While their study focused largely on Americans’ views of important policy decisions, their findings, they argue, apply beyond those domains.

If they are correct, we can use discussions of the apocalypse in the media over the past few decades as a barometer of prevailing public concerns.

Following this logic, we collected all articles mentioning the words “apocalypse” or “apocalyptic” from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post between Jan. 1, 1980, and Dec. 31, 2023. After filtering out articles centered on religion and entertainment, there were 9,380 articles that mentioned one or more of four prominent apocalyptic concerns: nuclear war, disease, climate change and AI.

Through the end of the Cold War, fears of nuclear apocalypse predominated not only in the newspaper data we assembled, but also in visual media such as the 1983 post-apocalyptic film The Day After, which was watched by as many as 100 million Americans.

By the 1990s, however, articles linking the word apocalypse to climate and disease – in roughly equal measure – had surpassed those focused on nuclear war. By the 2000s, and even more so during the 2010s, newspaper attention had turned squarely in the direction of environmental concerns.

The 2020s disrupted this pattern. COVID-19 caused a spike in articles mentioning the pandemic. There were almost three times as many stories linking disease to the apocalypse in the first four years of this decade compared to the entire 2010s.

In addition, while AI was practically absent from media coverage through 2015, recent technological breakthroughs generated more apocalypse articles touching on AI than on nuclear concerns in 2023 for the first time ever.

What should we fear most?

Do the apocalyptic fears we read about most actually pose the greatest danger to humanity? Some journalists have recently issued warnings that a nuclear war is more plausible than we realize.

That jibes with the perspective of scientists responsible for the Doomsday Clock who track what they think of as the critical threats to human existence. They focus principally on nuclear concerns, followed by climate, biological threats and AI.

It might appear that the use of apocalyptic language to describe these challenges represents an increasing secularization of the concept. For example, the philosopher Giorgio Agamben has argued that the media’s portrayal of COVID-19 as a potentially apocalyptic event reflects the replacement of religion by science. Similarly, the cultural historian Eva Horn has asserted that the contemporary vision of the end of the world is an apocalypse without God.

However, as the Pew poll demonstrates, apocalyptic thinking remains common among American Christians.

The key point is that both religious and secular views of the end of the world make use of the same word. The meaning of “apocalypse” has thus expanded in recent decades from an exclusively religious idea to include other, more human-driven apocalyptic scenarios, such as a “nuclear apocalypse,” a “climate apocalypse,” a “COVID-19 apocalypse” or an “AI apocalypse.”

In short, the reporting of apocalypses in the media does indeed provide a revelation – not of how the world will end but of the ever-increasing ways in which it could end. It also reveals a paradox: that people today often envision the future most vividly when they revive and adapt an ancient word.

Erik Bleich is Charles A. Dana Professor of Political Science, and Christopher Star a professor of classics, at Middlebury College.

These authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Looking up in Concord, N.H.

“Red and White Potential” (handwoven rug), by Polly Apfelbaum, in a two-person show with the late Alice Mackler, “The Potential of Women in Outer Space,’’ at Outer Space Arts, Concord, N.H., through June 1.

The McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center in Concord. The museum is dedicated to the memory of Christa McAuliffe, the Concord High School teacher selected by NASA out of over 11,000 applicants to be the first teacher in space, and Alan Shepard, the Derry, N.H., native and Navy test pilot who became the first American in space.

Chris Powell: How many more illegal immigrants can Conn. afford?

A map of U.S. states colored by their policy on “sanctuary cities” for illegal aliens. States in red have banned sanctuary cities statewide. States in blue are pro-sanctuary states.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut’s state government seems to think that illegal immigration isn’t a problem here, just -- maybe -- in other states. The other day state officials gathered with advocates of illegal immigration at the state Capitol to congratulate themselves on what a Connecticut Mirror report called the “explosive” demand for state insurance coverage for illegal immigrant children.

When this insurance, which is much like federal Medicaid insurance, was extended to illegal immigrant children age 12 and younger in January 2023, the state Department of Social Services estimated that about 4,000 children would be enrolled. But enrollees now exceed 11,000.

Now pregnant illegal immigrants qualify for this insurance as well and can continue it for a year after childbirth.

While it has not been publicized, children born to illegal immigrants in Connecticut also qualify for state government’s touted “baby bonds” program, in which the children are to receive as much as $24,000 in state money upon turning 18 -- money to be used for higher education, starting a business, buying a home or saving for retirement. The office of state Treasurer Erick Russell, which manages the program, lied to this writer to conceal the eligibility of the children of illegal immigrants but told the truth to a state legislator.

The deputy commissioner of the Social Services Department, Peter Hadler, gave the Mirror an absurd comment about the state’s medical insurance for illegal immigrant kids and pregnant illegal immigrants.

“Sometimes,” Hadler said, “there is trepidation on the part, especially of non-citizens, to participate in government programs. The good news is that that has not proven to be a barrier, and people are enrolling at strong rates and they’re seeking this out.”

Reluctance to claim government benefits? Maybe there was some back when the United States enforced its immigration law and immigrants were expected to cover their own expenses, but there is no reluctance today. Under the Biden administration and Democratic state administrations, illegal immigrants are qualifying not just for free medical insurance but also housing and monthly stipends.

There continues to be much agitation at the state Capitol to extend state medical insurance to all illegal immigrants in the state, though there are concerns about cost. It probably won’t happen during the current session of the General Assembly, since Gov. Ned Lamont is reluctant to give up the “fiscal guardrails” keeping order in state government's finances.

At the rally at the Capitol a spokesman for the coalition seeking to extend state medical insurance to all illegal immigrants in Connecticut said: “Health care is a fundamental human right, and no one should be denied access based on immigration status.”

But anyone can be treated without charge in a public hospital emergency room in the state, and is entering the United States illegally and living in Connecticut a fundamental human right too?

The advocates of extending state medical insurance to all illegal immigrants seem to think so. They seem to think there should be no controls to ensure that immigration can be assimilated without overwhelming public resources -- housing, medical care and insurance, and education -- and without sparking ethnic conflict and jeopardizing national security and the democratic and secular culture.

With its disastrous shortage of housing and long decline of its public education, Connecticut especially should have awakened to the danger by now.

While the campaign to subsidize illegal immigration dresses itself in righteousness and goodness, it devalues citizenship. It would increase dependence on government, enlarge the constituencies of the Democratic Party, increase the number of Democratic-dominated legislative districts, and drain the private sector. It would make the country ungovernable.

If what I see as the Biden administration’s open-borders policy continues and Connecticut continues its own subsidies for illegal immigration and continues its own nullification of federal immigration law, in a year or two the state easily could double its population of illegal immigrants, now estimated at 113,000. Millions of people in troubled and impoverished places like Guatemala, Venezuela, and most of Africa perceive the grand invitation. How many more does Connecticut want? How many more can it afford?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Deforming the landscape’

Webster, N.H., Congregational Church

“I was once reproved by a minister who was driving a poor beast to some meeting-house horse-sheds among the hills of New Hampshire, because I was bending my steps to a mountain-top on the Sabbath, instead of a church, when I would have gone farther than he to hear a true word spoken on that or any day. He declared that I was 'breaking the Lord's fourth commandment,' and proceeded to enumerate, in a sepulchral tone, the disasters which had befallen him whenever he had done any ordinary work on the Sabbath. He really thought that a god was on the watch to trip up those men who followed any secular work on this day, and did not see that it was the evil conscience of the workers that did it. The country is full of this superstition, so that when one enters a village, the church, not only really but from association, is the ugliest looking building in it, because it is the one in which human nature stoops the lowest and is most disgraced. Certainly, such temples as these shall erelong cease to deform the landscape. There are few things more disheartening and disgusting than when you are walking the streets of a strange village on the Sabbath, to hear a preacher shouting like a boatswain in a gale of wind, and thus harshly profaning the quiet atmosphere of the day.”

― Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), in A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers

Hell on the dirt

“Are You Not Entertained?” (oil on canvas), by Enfield, Conn.-based artist Devon Edwards, at Hartford Art School Galleries, West Hartford, Conn.

— Image courtesy of the artist

Enfield Shaker Village in 1910.

Then don't go there

Harkins Hall, at Providence College. The college’s first building, it was constructed in 1918—1919 in the Collegiate Gothic style then very popular on American campuses.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocalProv.com

There’s considerable tension these days at Providence College, a Catholic institution founded in 1917, over the feeling of LGBTQ students and employees that PC’s administration doesn’t adequately respect them (or agree with them?).

The central problem, of course, is that Catholic theology doesn’t mesh well with the desires, actions and beliefs of these students and staff. One wonders, then, why they’re at PC, given the many other institutions they could attend. And after all, PC, let alone the Roman Catholic Church, has no obligation to change its views.

I taught at the college for several years and always found it was run in a kindly way. That was before most people had heard of “LGBTQ”. I’m waiting for a few more letters to be added in our identity-obsessed times.

Spring burst

“Apple Trees in a Meadow,’’ by Providence-based painter Edward Bannister (1828-1901).

‘Greening the Labs’’ at MGH

Headquarters of Mass General Brigham, in Somerville

— Photo by Hospitalupdate

Edited from a New England Council report

“Mass General Brigham is expanding its ‘Greening the Lab’ initiative, which was concluded at five Massachusetts General Hospital labs earlier this year. Now, the research team behind the program is selecting 20 more labs from MGH’s parent organization to participate.

“The program comes from a partnership between MGH and My Green Lab, a San Diego-based nonprofit that helps increase the sustainability of biomedical research entities. The initial pilot program ensured the sustainability efforts would work in an academic medical center. According to Dr. Ann-Christine Duhaime, the associate director for research and publications at the Center for the Environment and Health at MGH, the initial results have been positive, showing that the program has effectively reduced costs, energy expenditure and hazardous-waste needs.

“‘The push to put more emphasis on sustainability has largely come from the junior researchers at the hospital,’’’ Duhaime said. ‘Creating a holistic program that brings all members of a lab together to focus on climate impact in addition to the clinical pursuits of their research has been a priority of the integration of the initiative, and initial findings have suggested that it’s increasing job satisfaction among participants.’

Chris Powell: U.S. students demonstrating for Palestinians display outrageous double standard about brutal, fascist Hamas

Pro-Palestinian college students near the Harvard campus, in Cambridge, Mass.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

At Yale University in New Haven, Conn., the University of Connecticut in Storrs, and a score of other institutions of higher education, students are protesting the support being given by the United States to Israel in its war with the Hamas regime in Gaza.

The students want their colleges to dissociate themselves from Israel and from military contractors whose munitions Israel uses. The students call for a ceasefire in the war and chant, "Palestine will be free."

But there were no protests at the colleges when Gaza attacked Israel on Oct. 7 last year, launching hundreds of rockets and murdering, raping, kidnapping, and mutilating civilians. The protests began only when Israel naturally retaliated and undertook to destroy Hamas. As Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir remarked a half century ago, the world loves Jews as victims but hates them when they fight back.

And what exactly do the students mean by "Palestine will be free"?

Do they mean freedom of speech, press, religion and assembly? Due process of law? Sexual freedom?

If so, the students' sympathies are laughably misplaced, for there have been no such freedoms in Gaza under Hamas rule, and few such freedoms elsewhere in the Arab world. Gaza's sympathizers on U.S. college campuses would be murdered within a week if they lived among the people are defending.

So maybe the calls of the students for a ceasefire in Gaza and freedom for Palestine really mean they want the area to be free of Jews. That always has been the objective of the people who have been running Gaza since Israel ended its occupation there in 2005. Back then Palestinians at last had their own state.

But two years later they elected Hamas, a movement sworn to Israel's destruction. Soon missiles were flying from Gaza into Israel. For years Israel tried to handle the problem merely defensively. Then came last October's barbaric attack.

Many people are appalled by the destruction and famine in Gaza. By some estimates more than half the structures in the territory have been destroyed or damaged beyond repair, and people are starving. Yet that is common in war.

Gaza today still looks better than Hamburg, Dresden, Berlin, Tokyo, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and dozens of other cities in Germany and Japan did in 1945. Those cities and many others had to be leveled by Allied bombing to compel the enemy's surrender.

Gaza's sympathizers complain that Israel's blockading Gaza has made starvation a weapon of war. But starvation always has been a weapon of war. With its submarines Germany tried to starve Britain out of both world wars, just as Britain and the United States, with naval blockades, tried to do the same to Germany. In 1945 the United States mined most Japanese harbors in what was frankly called Operation Starvation. It was highly effective and if undertaken earlier might have prevented the atomic bombings.

For starvation is a far more merciful weapon than bullets and bombs, as it gives an adversary more of a choice for survival.

Some of Israel's tactics are fairly criticized. But Israel is fighting for survival against an enemy that, at least until recent days, has refused even to contemplate the "two-state solution" the world presses on Israel. Indeed, the integrity of the Palestinian hate for Jews is amazingly pure, since most Palestinians still prefer their own destruction to co-existence. Their longstanding fanaticism now is generating similar fanaticism among Israelis, who years ago moved far closer to peace than the Palestinian factions ever went.

The protesting students don't help with their calls for a ceasefire. Since Israel was re-established by the United Nations in 1948 there have been dozens of ceasefires with the irreconcilables who surround the country. What is needed is not another ceasefire but peace -- that is, a permanent settlement.

Israel doesn't want to rule Gaza. But Gaza wants war, having broken a ceasefire last October. So Gaza will have to be the one to ask for peace, and Gaza, not Israel, is where pressure for peace first must be applied. =

Chris Powell is a veteran Connecticut-based columnist (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Bucket of bad sleep’

“A bucket of fish,’’ Mats Hagwall

“I let down my long line; it went falling; I pulled; up came

A bucket of bad sleep in which tongues were sloshing about

Like frogs and dark fish, breaking the surface of silence….’’

— From “The Angler’s Story,’’ by American poet and Yale Prof. John Hollander (1929-2013). He lived in Woodbridge, Conn.

In Woodbridge, the Darling House Museum, built in 1774

— Photo by Jerry Dougherty

'Forms of connection'

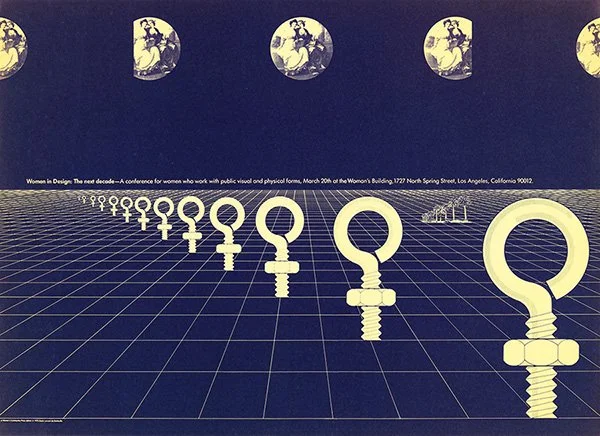

“Women in Design: The Next Decade” (Diazo lithograph on paper), by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, in her show “Community, Activism and Design,’’ at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.

— Courtesy Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

She says:

“From the start, I saw that the direct expression of a plurality of voices within each community could carry the immediacy of conversations, and that content and site combine to inform my choice of materials and processes. Over time open-ended forms, processes and materials offered me different ways to extend to others an invitation to participate in the meaning of each work. Through listening I have been able to reflect local populations and translate that connection first in ephemera and then in site specific, permanent installations integrated into specific places here in the states and abroad. The vivid forms of connection to people and place has become recognizable as my work…’’

Glassy-eyed in Vermont

This work by Mr. Bernbaum is in the show “Sand to Glass: The Nature of Glass,’’ at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester, June 8-Sept. 22

Mr. Bernbaum says on his Web site:

“I am most interested in color, especially color relationships in the works I create in blown glass. Utilizing traditional Italian cane (or striping) techniques in new and personalized ways is the driving force behind most of my current designs.

“I consider the pieces I make to be documents along the way of a (hopefully) life-long journey of both refining the necessary skills and developing the patience one needs in order to create with this captivating and mesmerizing molten material.’’

The elegant court house In Manchester. It was built in 1822.

Gird yourself for noisy double brood of cicadas

Cicada in Princeton, N.J., in 2014

— Photo by Pmjacoby

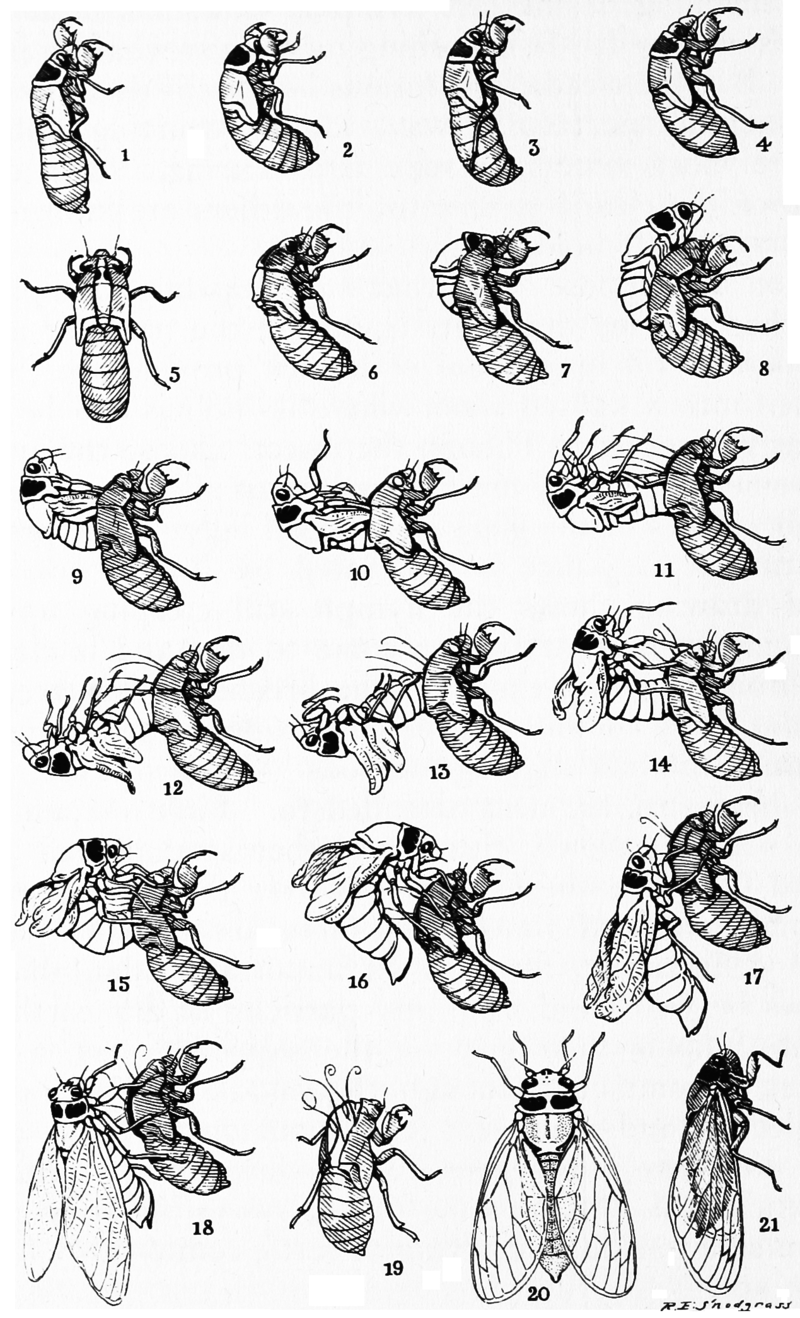

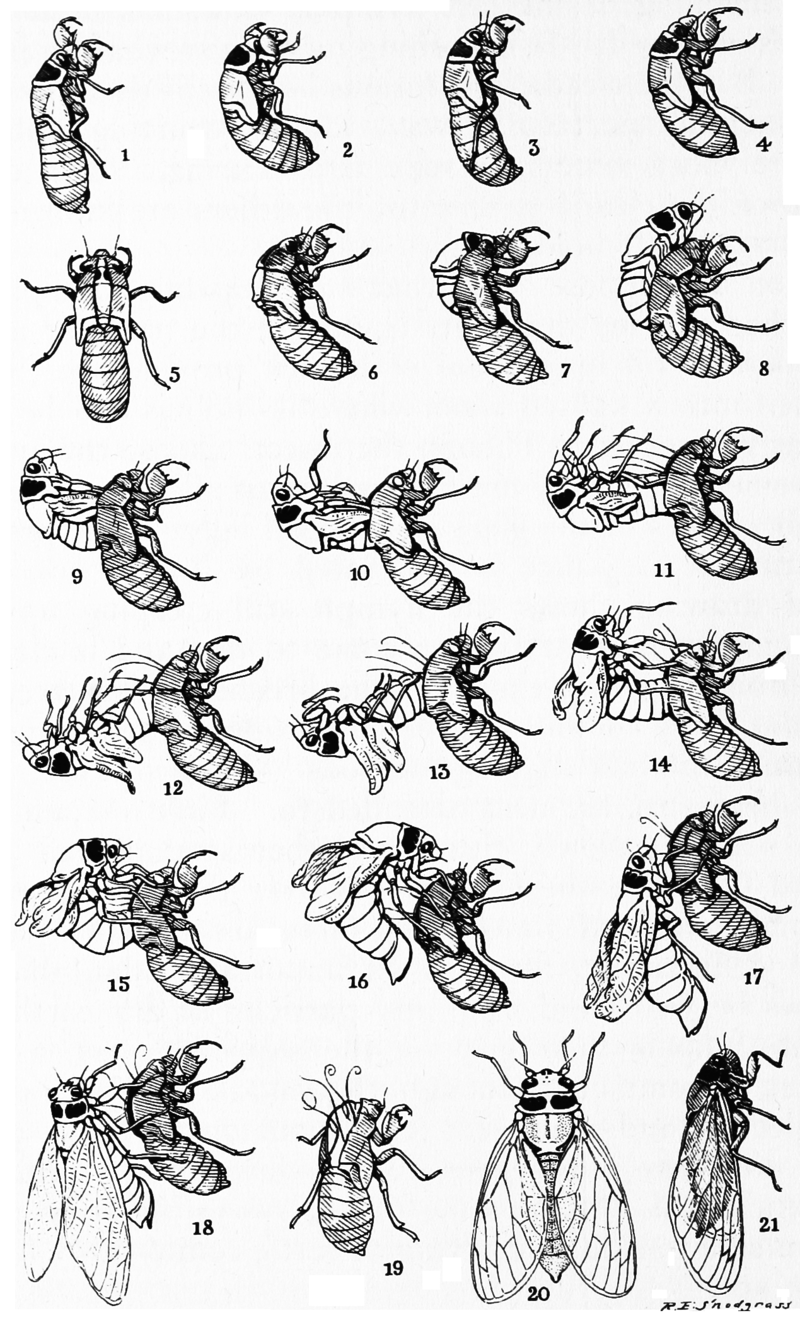

The article with additional graphics

John Cooley is an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and Chris Simons a senior research scientist of ecology and evoluttionary biology, at the University of Connecticut in Storrs.

John Cooley receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society.

Chris Simon has received funding from the National Science Foundation, the Fulbright Foundation, the National Geographic Society and the New Zealand Marsden Fund.

In the wake of North America’s recent solar eclipse, another historic natural event is on the horizon. From now through June 2024, the largest brood of 13-year cicadas, known as Brood XIX, will co-emerge with a Midwestern brood of 17-year cicadas, Brood XIII.

This event will affect 17 states, from Maryland west to Iowa and south into Arkansas, Alabama and northern Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia and Maryland. A co-emergence like this of two specific broods with different life cycles happens only once every 221 years. The last time these two groups emerged together was in 1803, when Thomas Jefferson was president.

For about four weeks, scattered wooded and suburban areas will ring with cicadas’ distinctive whistling, buzzing and chirping mating calls. After mating, each female will lay hundreds of eggs in pencil-size tree branches. Then the adult cicadas will die. Once the eggs hatch, new cicada nymphs will fall from the trees and burrow back underground, starting the cycle again.

There are perhaps 3,000 to 5,000 species of cicadas around the world, but the 13- and 17-year periodical cicadas of the eastern U.S. appear to be unique in combining long juvenile development times underground with synchronized, mass adult emergences. There are two other known periodical cicadas in the world, one in northeast India and one in Fiji, but these have only four-year and eight-year life cycles, respectively.

Periodical cicadas raise many questions for entomologists and the public alike. What do cicadas do underground for 13 or 17 years? Why are their life cycles so long? Why are they synchronized? Will the two broods emerging this spring interact? How can citizen scientists help to document this emergence? And is climate change affecting this wonder of the insect world?

We study periodical cicadas to understand questions about biodiversity, biogeography, behavior and ecology – the evolution, natural history and geographic distribution of life. It’s no accident that the scientific name for periodical 13- and 17-year cicadas is Magicicada, shortened from “magic cicada.”

Illinois is expected to be ground zero for the dual emergence of two periodical cicada broods in 2024.

Transformation from mature cicada nymph to adult.

Ancient visitors

As species, periodical cicadas are older than the forests that they inhabit. Molecular analysis has shown that about 4 million years ago, the ancestor of the current Magicicada species split into two lineages. Some 1.5 million years later, one of those lineages split again. The resulting three lineages are the basis of the modern periodical cicada species groups, Decim, Cassini and Decula.

Early American colonists first encountered periodical cicadas in Massachusetts. The sudden appearance of so many insects reminded them of biblical plagues of locusts, which are a type of grasshopper. That’s how the name “locust” became incorrectly associated with cicadas in North America.

During the 19th century, notable entomologists such as Benjamin Walsh, C.V. Riley and Charles Marlatt worked out the astonishing biology of periodical cicadas. They established that unlike locusts or other grasshoppers, cicadas don’t chew leaves, decimate crops or fly in swarms.

Instead, these insects spend most of their lives out of sight, growing underground and feeding on plant roots as they pass through five juvenile stages. Their synchronized emergences are predictable, occurring on a clockwork schedule of 17 years in the North and 13 years in the South and Mississippi Valley. There are multiple, regional year classes, known as broods.

Acting in unison

The key feature of Magicicada biology is that these insects emerge synchronously in huge numbers – as high as 1.5 million per acre. This increases their chances of accomplishing their key mission aboveground: finding mates.

Dense emergences also provide what scientists call a predator-satiation or safety-in-numbers defense. Any predator that feeds on cicadas, whether it’s a fox, squirrel, bat or bird, will eat its fill long before it consumes all of the insects in the area, leaving many survivors behind.

While periodical cicadas largely come out on schedule every 17 or 13 years, often a small group emerges four years early or late. Early-emerging cicadas may be faster-growing individuals that had access to abundant food, and the laggards may be individuals that subsisted with less.

If growing conditions change over time, as is happening now with climate warming, having the ability to make this kind of life cycle switch and come out either four years early in favorable times or four years late in more difficult times becomes important. If a sudden warm or cold phase causes a large number of cicadas to come out off schedule by four years, the insects can emerge in sufficient numbers to satiate predators and shift to a new schedule.

‘From the cellar stairs’

Union Village, in Thetford, Vt: Methodist church and defunct School House.

Photo by EdwardEMeyer

“I was happy, but I am now in possession of knowledge that this is wrong. Happiness isn't so bad for a woman. She gets fatter, she gets older, she could lie down, nuzzling a regiment of men and little kids, she could just die of the pleasure. But men are different, they have to own money, or they have to be famous, or everybody on the block has to look up to them from the cellar stairs.”

— Grace Paley (1922-2007), American writer. A native of New York City, she lived in Thetford, Vt., in her later years.

Thetford in 1912.

Chris Powell: The wild ‘Kia Boyz’ may represent Conn.’s grim future

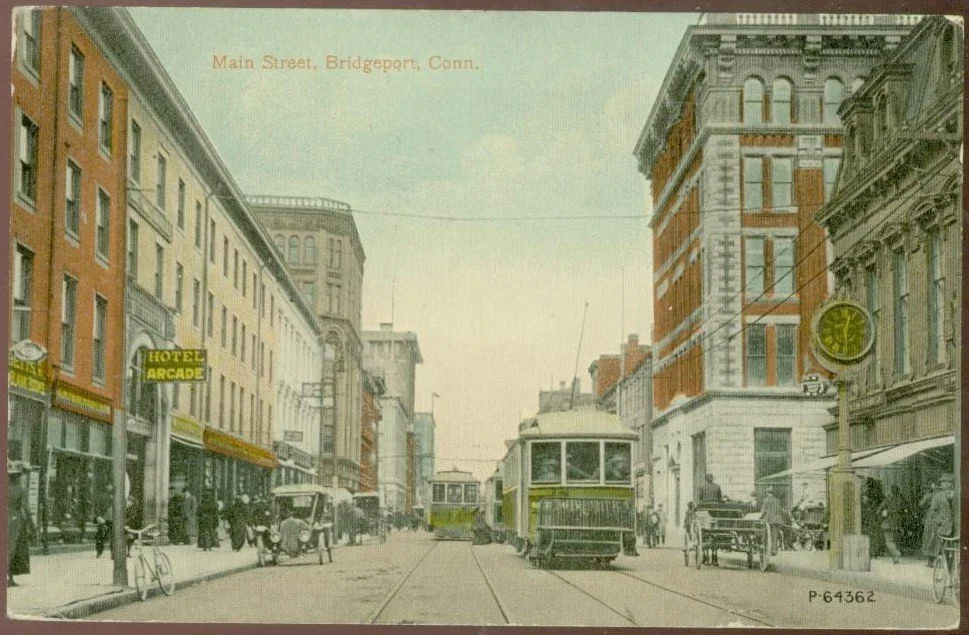

Downtown Bridgeport in 1912. Bridgeport was an industrial powerhouse for decades.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

What may prove to be Connecticut's best journalism for many years was a 44-minute video documentary of sorts posted last week on YouTube by freelancer Andrew Callaghan and brought to the state's attention by CTCapitolReport.com.

Callaghan gained the confidence of three teenage gangsters from Bridgeport and video-recorded them on their daily rampages -- breaking into and stealing cars day and night throughout the state, speeding away wildly along highways and residential streets, risking death and the death of others, defeating police pursuit, and boasting that no one can catch them.

Of course the young gangsters might be caught, insofar as Callaghan repeatedly located them and even joined them at a government housing project in Bridgeport, where, he found, stolen cars are regularly being "sold" to other young gangsters for a mere hundred dollars or so, the contents of the cars having more value than the cars themselves, which are soon abandoned since they can't be acquired legally.

Apparently the Bridgeport police were not yet aware of or interested in the use of the housing project as a stolen car market. Nor, apparently, was Mayor Joe Ganim, though his recent re-election campaign was noted for soliciting absentee ballots from public-housing residents who may have feared that keeping their apartments required such cooperation with the regime.

Despite the harm they were doing, the kids seemed more lost and nihilistic than evil, glad that someone from another world was paying attention to them. As they sat on the roof of a small abandoned house, taking a break from their mayhem, Callaghan even got them to reflect briefly on their lack of parenting and particularly their lack of present fathers.

The young gangsters call themselves the Connecticut Kia Boyz, since most of their target vehicles are Kias, which became notorious for the ease of bypassing their ignition systems with a screwdriver and USB cable.

It is hard not to see the Kia Boyz as the country's future -- the vanguard of the ever-growing urban underclass, products of the family-destroying welfare system; of schools that pay their employees well but fail to educate because they can't educate when their primary policy is social promotion and parents are no help; and of a criminal-justice system that pretends that social work actually works and is preferable to imprisoning young repeat offenders, giving them what feckless state legislators call "the help they need" without ever defining or delivering it.

What the Kia Boyz and the hundreds of thousands like them around the country need most is parents. But no one in authority in Connecticut dares to inquire into what has happened to parents and particularly to fathers, and why. That's because such an inquiry might distress the many government employees and others who make their livings doing what doesn't work or even makes things worse.]

Anyone daring to inquire into the collapse of the family would also risk accusations of racism, since fatherlessness and poverty are racially disproportionate,.

So the country's nearly comprehensive abandonment of behavioral standards continues, worsened by the crushing pressure imposed on schools, hospitals, welfare agencies and government budgets by the millions of immigrants illegally entering the country in recent years.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the social scientist who became a great U.S. senator from New York, saw it all coming in the famous 1965 report that bears his name.

Moynihan wrote: "From the wild Irish slums of the 19th-century Eastern seaboard to the riot-torn suburbs of Los Angeles, there is one unmistakable lesson in American history: A community that allows a large number of men to grow up in broken families, dominated by women, never acquiring any stable relationship to male authority, never acquiring any set of rational expectations about the future -- that community asks for and gets chaos. Crime, violence, unrest, disorder -- most particularly the furious, unrestrained lashing out at the whole social structure -- that is not only to be expected; it is very near to inevitable. And it is richly deserved."

Six decades later Moynihan's prophecy is still ignored even as new horrors fulfill it almost every day.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Llewellyn King: Entering an iron age for batteries

The old steel mill in Weirton, W.Va., from which a Massachusetts company’s perhaps revolutionary iron-air batteries will be shipped.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Since electricity was first deployed, there has been a missing link: storage.

The lead-acid battery was first developed in 1859 and has been refined to the effective, utilitarian box we have in cars today. Gone are the days when you sometimes had to top up the car battery with sulfuric acid and, often, distilled water.

These batteries, these workhorses, never made it far beyond their essential role in automobiles. Although early car manufacturers thought that the future of the automobile would belong to electricity, it was the internal-combustion engine that took over.

While battery research continues unabated – especially after the energy crisis that unfolded after the fall of 1973 -- it wasn’t until the lithium-ion battery arrived in the 1980s that batteries became a transformative technology. From cell phones to Teslas, they have upended the world of stored electricity.

Lithium-ion was the clear winner. It is light and suitable for transportation. It has also been the primary battery for utilities, which have been installing them at breakneck speed. But they are costly, and lithium is at the end of a troubled supply chain.

Batteries are essential to realizing the full potential of electricity generated from wind and solar. They provide power when the sun has set or the wind isn’t blowing. They can capture surplus production in the middle of the day when states like California and Arizona already have overproduction of solar power and it becomes negative energy, wasted.

Enter iron-air batteries. That is right: Iron with an “r,” which is the basic material in steel and one of the most plentiful elements on Earth.

Iron-air batteries use rusting as their central technology. In an iron-air battery, iron, water and air are the components. The iron rusts to discharge power and the rusting is reversed to charge the battery.

Form Energy, based in Somerville, Mass., will be shipping these revolutionary batteries to utilities late this year or early next from their manufacturing plant at the site of the old steel mill on the Ohio River in Weirton, W.Va. This means transportation infrastructure for heavy loads is already in place.

Form Energy got started with two battery experts talking: Mateo Jaramillo, the head of battery development at Tesla, and Yet-Ming Chiang, a professor at MIT who devoted his career to the study of batteries, primarily lithium. Indeed, he told me when I met with him in Somerville, that he fathered two successful battery companies using lithium.

But clearly, iron-air is Chiang’s passion now — a palpable passion. He is the chief scientific officer at Form Energy and remains professor of materials science and engineering and professor of ceramics at MIT.

Chiang, Jaramillo and three others founded Form Energy, in 2017. Now it has contracts with five utilities to provide batteries and appears to be fulfilling the dearest wish of the utilities: a battery that can provide electricity over long periods of time, like 100 hours. Lithium-ion batteries draw down quickly — usually in two or four hours, before they must be recharged.

An iron-air battery is capable of slow discharge over days, not hours. Therefore, it can capture electricity when the sun is blazing and the wind is blowing — which tends to drop in the afternoon just when utilities are beginning to experience their peak load, which is early evening.

Iron is very heavy and so the use of iron-air technology would appear to be limited to utilities where weight isn’t a problem and where the need for long, long drawdown times are needed; for example, when the wind doesn’t blow for several days.

Jaramillo told me the company has finished its funding and is well-set financially. It has raised $860 million and was given $290 million by the state of West Virginia,

The smart money has noticed: Early funders include Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos. Is a new Iron Age at hand?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email address is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

It will calm down

“Angry Nimbus” (limited edition fine art photograph), by Robert Thomas, at Spectrum Art Gallery, Centerbrook, Conn., a village in the town of Essex.

Early 20th Century postcard.

Before Fenway

Playing at the Huntington Avenue field in the early 20th Century.

Excerpted from The Boston Guardian

“The Huntington Avenue American League Baseball Grounds was one of the most popular and well-attended baseball fields in Boston in the early 20th Century. The large open-air field was on Huntington Avenue, just west of Massachusetts Avenue and opposite the Boston Opera House. It was the first home of the Boston Red Sox.

“In 1901, ground was officially broken in the Fenway area of the city for the new baseball field, with a covered grandstand and high wood fences, that was to have a capacity of 11,500 spectators….

“The baseball field was the site of the World Series game between the current American and National Leagues in 1903, the first perfect game in the modern era, thrown by Cy Young in 1904.’’

Hit this link to read the whole article, by historian Anthony Sammarco

Using fungi instead of petroleum

A series of fungi.

— Collage by BorgQueen

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Anything we can do to get off many manmade toxic chemicals the better, in small and large places. Researchers and business have been stepping up efforts to get off problematical chemicals by turning to natural solutions.

Boston’s WBUR reports that one quirky example is on Nantucket, which is experimenting with “MycoBuoys,” made from the root-like part of mushrooms (which, of course, are fungi), to replace petroleum-based Styrofoam buoys used in scallop, oyster, and mussel aquaculture to hold up spat collectors. The Styrofoam degrades, releasing microplastics that pose health risks to animal life in general. In this case, they may have been harming shellfish reproduction.

When shellfish reproduce, they spawn tiny larvae that move in the water until they find a structure to settle on. Once the larvae permanently attach to a surface, they are known as spat and, hopefully, grow to harvestable-sized shellfish.

The hope is that the buoys will last five to eight months. Town officials will see if their use can increase the number of scallops. If so, that could be an economic boon. Scallops sell for a pretty price.

Fungi can be used in a wide variety of ways to reduce the use of manmade chemicals. These include medicine, fuel, fertilizers, cosmetics, clothing and footwear. And reducing the production of manmade chemicals reduces the burning of fossil fuels.

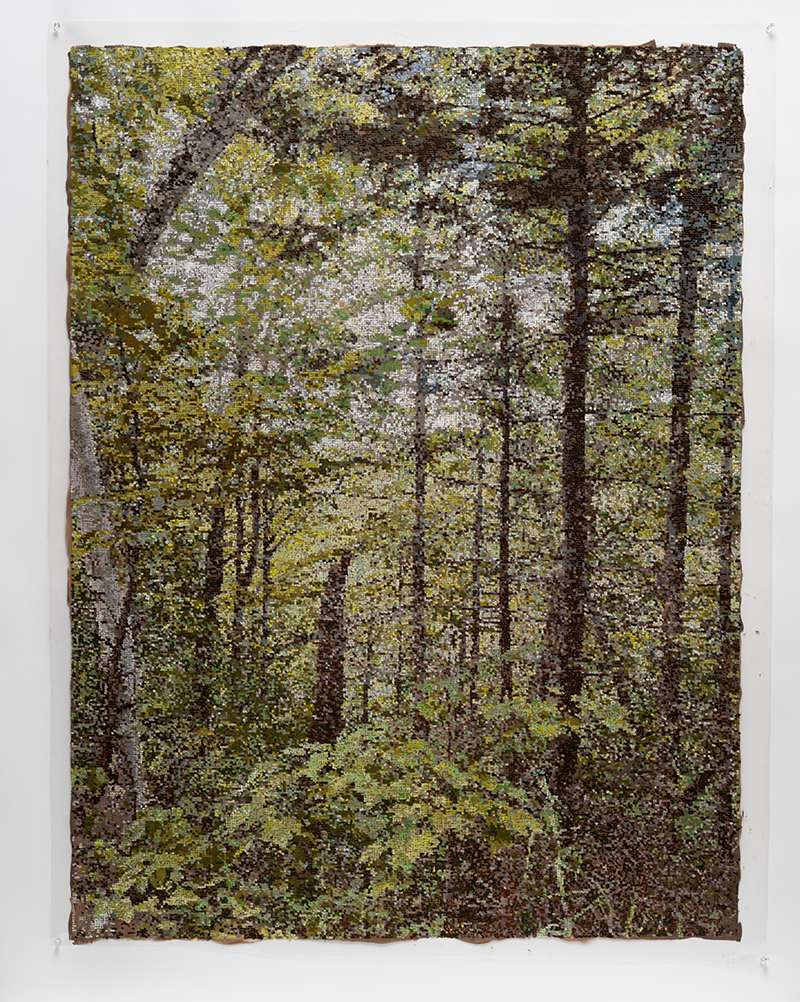

Woods on the grid

“The Woods Maine” (grid-based painting), by Rhode Island artist Kristin Lamb, at the Jennifer Terzian Gallery, Litchfield, Conn., April 27-June 15.

—Image courtesy of the gallery

The gallery promotes Ms. Lamb’s labor-intensive grid-based paintings {that} focus on the beauty of lush, green New England forests. Ms. Lamb says her work is a“blur between a focused photorealism, a computer-generated pattern and a fetishized repetition of an acrylic paint mark.’’