Gird yourself for noisy double brood of cicadas

Cicada in Princeton, N.J., in 2014

— Photo by Pmjacoby

The article with additional graphics

John Cooley is an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and Chris Simons a senior research scientist of ecology and evoluttionary biology, at the University of Connecticut in Storrs.

John Cooley receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society.

Chris Simon has received funding from the National Science Foundation, the Fulbright Foundation, the National Geographic Society and the New Zealand Marsden Fund.

In the wake of North America’s recent solar eclipse, another historic natural event is on the horizon. From now through June 2024, the largest brood of 13-year cicadas, known as Brood XIX, will co-emerge with a Midwestern brood of 17-year cicadas, Brood XIII.

This event will affect 17 states, from Maryland west to Iowa and south into Arkansas, Alabama and northern Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia and Maryland. A co-emergence like this of two specific broods with different life cycles happens only once every 221 years. The last time these two groups emerged together was in 1803, when Thomas Jefferson was president.

For about four weeks, scattered wooded and suburban areas will ring with cicadas’ distinctive whistling, buzzing and chirping mating calls. After mating, each female will lay hundreds of eggs in pencil-size tree branches. Then the adult cicadas will die. Once the eggs hatch, new cicada nymphs will fall from the trees and burrow back underground, starting the cycle again.

There are perhaps 3,000 to 5,000 species of cicadas around the world, but the 13- and 17-year periodical cicadas of the eastern U.S. appear to be unique in combining long juvenile development times underground with synchronized, mass adult emergences. There are two other known periodical cicadas in the world, one in northeast India and one in Fiji, but these have only four-year and eight-year life cycles, respectively.

Periodical cicadas raise many questions for entomologists and the public alike. What do cicadas do underground for 13 or 17 years? Why are their life cycles so long? Why are they synchronized? Will the two broods emerging this spring interact? How can citizen scientists help to document this emergence? And is climate change affecting this wonder of the insect world?

We study periodical cicadas to understand questions about biodiversity, biogeography, behavior and ecology – the evolution, natural history and geographic distribution of life. It’s no accident that the scientific name for periodical 13- and 17-year cicadas is Magicicada, shortened from “magic cicada.”

Illinois is expected to be ground zero for the dual emergence of two periodical cicada broods in 2024.

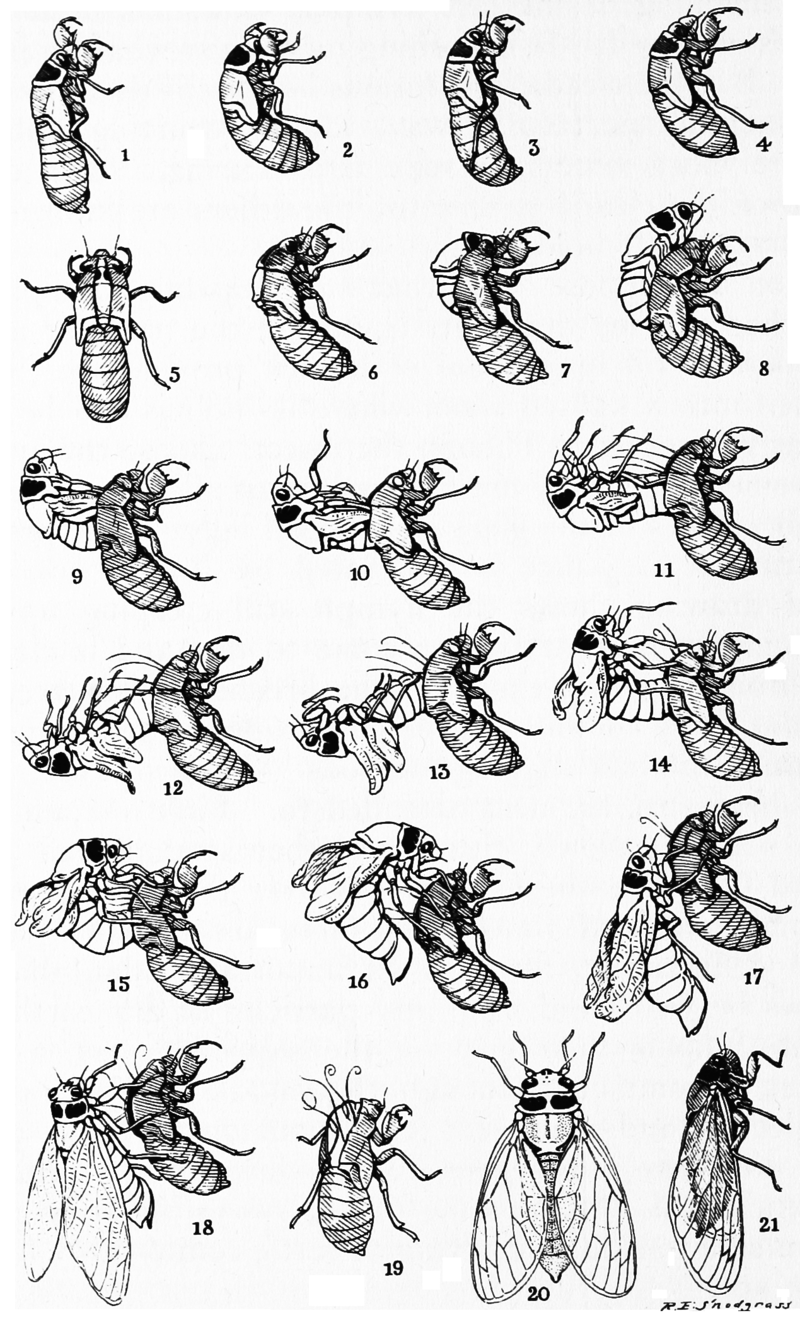

Transformation from mature cicada nymph to adult.

Ancient visitors

As species, periodical cicadas are older than the forests that they inhabit. Molecular analysis has shown that about 4 million years ago, the ancestor of the current Magicicada species split into two lineages. Some 1.5 million years later, one of those lineages split again. The resulting three lineages are the basis of the modern periodical cicada species groups, Decim, Cassini and Decula.

Early American colonists first encountered periodical cicadas in Massachusetts. The sudden appearance of so many insects reminded them of biblical plagues of locusts, which are a type of grasshopper. That’s how the name “locust” became incorrectly associated with cicadas in North America.

During the 19th century, notable entomologists such as Benjamin Walsh, C.V. Riley and Charles Marlatt worked out the astonishing biology of periodical cicadas. They established that unlike locusts or other grasshoppers, cicadas don’t chew leaves, decimate crops or fly in swarms.

Instead, these insects spend most of their lives out of sight, growing underground and feeding on plant roots as they pass through five juvenile stages. Their synchronized emergences are predictable, occurring on a clockwork schedule of 17 years in the North and 13 years in the South and Mississippi Valley. There are multiple, regional year classes, known as broods.

Acting in unison

The key feature of Magicicada biology is that these insects emerge synchronously in huge numbers – as high as 1.5 million per acre. This increases their chances of accomplishing their key mission aboveground: finding mates.

Dense emergences also provide what scientists call a predator-satiation or safety-in-numbers defense. Any predator that feeds on cicadas, whether it’s a fox, squirrel, bat or bird, will eat its fill long before it consumes all of the insects in the area, leaving many survivors behind.

While periodical cicadas largely come out on schedule every 17 or 13 years, often a small group emerges four years early or late. Early-emerging cicadas may be faster-growing individuals that had access to abundant food, and the laggards may be individuals that subsisted with less.

If growing conditions change over time, as is happening now with climate warming, having the ability to make this kind of life cycle switch and come out either four years early in favorable times or four years late in more difficult times becomes important. If a sudden warm or cold phase causes a large number of cicadas to come out off schedule by four years, the insects can emerge in sufficient numbers to satiate predators and shift to a new schedule.