Between dislocation and belonging

From Yvette Mayorga’s current show, “Dreaming of You,’’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, in Greenwich, Conn.

The museum says:

“Inspired by her mother’s work at a bakery after immigrating to the United States from Jalisco, Mexico, Mayorga frosts thick acrylics onto sculptures and canvases with piping bags and icing tips to achieve delectable textures. … Mayorga’s handicraft intimately immerses the viewer in the tension between dislocation and belonging that defined her girlhood as a first-generation Mexican-American in the Midwest in the ‘90s and 2000s.’’

Llewellyn King: More and more, be happy you speak English

English-speaking peoples monument on Bush House, London

— Photo by Goodwillgames

ATHENS

If you hold a professional certificate, whether it is for information technology or language proficiency, or if you hold one for best practices in project management, you may have a Greek entrepreneur to thank.

He is Byron Nicolaides, founder and CEO of PeopleCert, the global testing company based in Athens.

I sat down with him in his office in the city’s center recently to find out how a businessman in Greece could affect standards of conduct and performance around the world.

It is a tale that begins with a very poor Greek family living in Istanbul — Nicolaides uses the old name for the Turkish capital, Constantinople, where once, he said, there was a community of more than 100,000 Greeks, which has dwindled to just 2,000 today. His parents were English teachers and had no fixed incomes. “Sometimes,” he said, “they would be paid in kind with a chicken or some bread.”

From this poverty their son, Byron, rose to be one of the richest men in Greece or Turkey. The company he created in 2000, is a global leader in professional and language skills certification. In 2021, it became the first Greek unicorn, reaching a capital value of more than $1 billion.

Note that his parents were English teachers — and this is important.

As I talked to Nicolaides, he enthused about the universality of English and how it has been a unifying force in the world. No worry about how English may crush marginal but traditional languages.

Nicolaides is passionate about English. Without it, he wouldn’t be the success he is today. He sees it as a great binding force, a great way for peoples and nations to talk to each other and to avoid friction. He wants everyone to know English

He asked me, “What is the second-biggest language in the world?” I look at the ceiling and start thinking about the two large population countries, India and China. I say uncertainly, “Hindi.”

With boyish happiness, Nicolaides, a young 65 of athletic build and a full head of hair, says, “Bad English.”

His enthusiasm for the English language becomes a man whose company tests English proficiency around the world — and he lists Fortune 500 companies (including Goldman Sachs and Citibank), NASA, the FBI, the CIA, universities and other institutions.

As Nicolaides unspools his life story, one is captivated by how a poor boy of Greek heritage made his way to Bosphorus University, where he earned a BA in business administration, and then to the University of La Verne in Southern California, where he earned an MBA.

Whereas Nicolaides’ upbringing and education in Turkey might seem to be a challenge — Turkey and Greece are seldom on the best of terms — it has been a great advantage to him.

His break was in 1986, when he went to work for Merrill Lynch in Greece, becoming its highest earner. The company was looking for someone to open the Turkish market, offering a $5,000 to $10,000 signing bonus. Nicolaides took the bonus, and the job made him a millionaire by age 31.

At that point, he told me, he had more money than he knew what to do with, so he did the thing all Greeks with money do, “I went into shipping.”

Nicolaides spent a year in the shipping industry and hated it. He said the only thing all the other shipping millionaires could talk about was “money, money, money.” Although today he has much, much more money, he feels he is helping humanity with the educational purpose of PeopleCert.

If he lucked out beyond expectations with Merrill Lynch, he lucked out with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, too, albeit indirectly.

During the Falklands War, Nicolaides said, the Iron Lady was appalled at the lack of interoperability between the British forces. She demanded the introduction of the kind of best practices and certification which later became a pillar of PeopleCert.

Thatcher’s requirement was developed by a British company in which Nicolaides had an investment. Later, he bought that company and PeopleCert became unstoppable: It has certified 7 million people around the world and is growing at 36 percent a year.

Reflecting on this odyssey by a golden Greek, I realize that native English speakers start with a huge advantage in that the world is open in a way that it isn’t to those who don’t speak English.

When I first visited Athens in the 1960s, getting around depended on finding an English speaker. They were few and far between. Today everyone seems to speak English, and well.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Iskand.

Byron Nicolaides

Observation and reinvention

Work by Marlboro, Vt.-based Cathy Osman, in her show “I Chose These Things,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through March 31. These are still lifes inspired by the landscape of southern Vermont.

Her artist’s statement says:

“The foundation of my work grows from a deeply felt respect and connection to my natural surroundings. As a painter and printmaker living in Southern Vermont, I am attentive to the landscape’s inherent beauty. The work is a synthesis of the observed, a quirky need to re-invent through process, the particularity of materials, as a means to reconsider the appearance of things.

“This series of images incorporates renderings of the humble honey bee, generic references to birds, cell structures, and industrial detritus. The environmental and biological stresses affecting an insect, for instance, are not merely emblematic, but serve as a barometer reflecting the enormity of impact that the loss of insect life will have upon the security of our world.

“The work is often collage-based. I am constructing primarily using materials I surface through my printing press with different surface textures and color. With this raw material, I layer the collages, creating a substrata made dense with an overlay of marks, color and assemblage of shapes. Some of the work can be read as landscape, others as fragments of the man-made.

“Recently I have returned to oil painting, focusing my eye on the observed and invented structure of flowers and plants.’’

The Whetstone Inn, on the Marlboro, Vt., Town Common, was built c. 1775

— Photo by Beyond My Ken

Housing solutions should include thinking small

Tiny homes in Detroit

Photo by Andrew Jameson

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Exurban/suburban Burrillville, R.I., has admirably been in the forefront of making housing available to people with minimal means. And I particularly like that the town has tried to concentrate new housing in its village centers. This reduces sprawl and makes it easier for people to shop without having to use a car.

Meanwhile, in a national sign of moves to make housing, including owner-occupied dwellings, more affordable, very small houses (some only 400 square feet) are going up in some communities as larger, but still small, houses become increasingly unaffordable to people with low or moderate incomes.

In 2022, the average size of a single-family home in the United States was 2,522 square feet. Although in the past five years American homes have been shrinking a bit, since 1975, they have almost doubled in size. That’s even as the size of families has shrunk, more people are living alone and the population is aging.

It's about time that many more smaller dwellings were built.

Finally, look for more confrontations between state governments that are pressing communities to change zoning ordinances and make other changes to encourage more “affordable” housing construction, especially near public transit and shopping. Consider Milton, Mass., some of which is very affluent, rejecting in a referendum a state mandate meant to promote affordable housing in communities with MBTA lines. The state will yank some state grants to the town unless it swiftly comes into compliance.

Read:

Excluded: How Snob Zoning, NIMBYism and Class Bias Build the Walls We Don’t See, by Richard D. Kahlenberg

The communities are legal children of the state, and the housing crisis will demand that it compel some of the pull-up-the-bridge towns to change their housing policies. This is not just a matter of fairness. The long-term health of our economy will depend in no small part on adequate housing for the full range of workers and their families.

Maybe there should be a surtax on some vacant urban and suburban land to encourage building housing there.

The 18th Century Suffolk Resolves House, in Milton, now a museum

To 'reinvigorate the landscape'

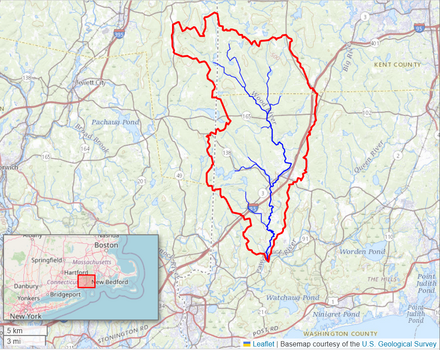

Work in Ana Flores’s show “Wood River,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, through March 31.

The gallery says the show features sculpture from her “Sacred Grove’’ and “Cultivate’’ series, “celebrating our powers to rebuild and reinvigorate the landscape, and offering a glint of optimism in the face of our dangerous human default of destruction and deforestation. Flores lives at the edge of the forest by the Wood River in southern Rhode Island. Working manually on her land over the years, she feels the land also worked on her, reawakening a deep ‘sense of place.’ For Flores, the phrase is no longer metaphorical. The artist contends that her sense of place is just as real as her sense of smell or sight—a multi-sensory connection and understanding of not only the biological history of a place, but also of its layered human traces.’’

The Wood River watershed

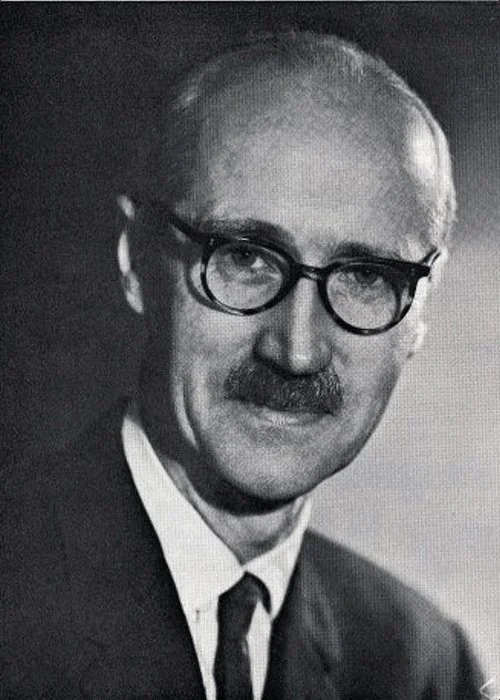

David Warsh: What an economist and public servant! And his brother was a spy

Sir Alexander Cairncross

Milton Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in 1976, but something more important to economics happened that year, and I don’t mean the bicentennial of the American Revolution. The Glasgow Edition of the Works of Adam Smith appeared that year as well, timed to commemorate the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations.

“Modern economics can be said to have begun with the discovery of the market,” began Sir Alexander Cairncross, chancellor of the University of Glasgow, in his opening address to the convocation that introduced the new edition.

He continued:

“Although the term ‘market economy’ had yet to be invented, its essential features have debated the strength and limitations of market forces [ever since] and have rejoiced in their superior understanding of these forces. The state, by contrast, needed no such discovery.”

Cultural entrepreneurs in economics, even the most effective among them, such as John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, do their work against the background of hard-earned knowledge of others, standing on the shoulders of giants and all that.

Eight beautiful volumes had rolled off the presses: two containing The Wealth of Nations; another with Smith’s first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments,; three more volumes of essays, on philosophical subjects (which includes the famous essay on the history of astronomy), jurisprudence, and rhetoric and belles letters; a collection of correspondence and some odds and ends; and, in the eighth, an index to them all.

Each contains introductions by top Smith scholars, with edifying asides tucked in among the footnotes. Two companion volumes accompanied the release, published by Oxford University Press: Essays on Adam Smith, and The Market and the State: Essays in Honor of Adam Smith, by way of penance. Smith had been educated at the University of Glasgow but scorned Oxford, where he spent six post-graduate years, mostly reading. Inexpensive volumes of any or all of the Glasgow edition can be had from the Liberty Fund.

A feast, in other words, for those interested in thinking about such things.

One such was Cairncross, whose Wikipedia entry begins this way:

“Sir Alexander Kirkland Cairncross KCMG FRSE FBA (11 February 1911 – 21 October 1998), known as Sir Alec Cairncross, was a British economist. He was the brother of the spy John Cairncross [worth reading!] and father of journalist Frances Cairncross and public health engineer and epidemiologist Sandy Cairncross.”

More to our point, for twenty-five years Cairncross was chancellor of Glasgow University (1971-1996). It was he who commissioned the Glasgow edition of Smith. He delivered the inaugural address I quoted above.

Before that, however, Cairncross became an economist, as an under graduate at Glasgow and then, beginning in 1932, at Trinity College, Cambridge, under John Maynard Keynes and his increasingly incensed rival, Dennis Robertson. Keynes published his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money to great excitement in 1936; Robertson steered Cairncross away from theory and into applied economics. After graduating with honors, he returned to Glasgow as a lecturer and wrote a textbook.

His service in government during World War II and after was extensive and exemplary: the Ministry of Aircraft Production; Treasury representative at the Potsdam Conference; a stint at The Economist; adviser first to the Board of Trade, then to the Organization for European Economic Cooperation; 10 years as Professor of Applied Economics at Glasgow; then, for another decade, various high-ranking positions in the Treasury. The appointment as Glasgow’s chancellor came in 1971.

If you are interested in post-war Britain, particularly the Sixties, the Royal Academy’s biographical minute on Cairncross makes interesting reading. Quietly told in 1964 about his brother’s treachery as a paid agent of the KGB, he called it “perhaps the greatest shock I ever experienced.”

Cairncross was a Keynesian economist, his biographers say. He was critical of monetarism and dismissed the idea of a “natural” rate of unemployment as absurd. He considered that industrial planning, while necessary in wartime, was no model for peacetime governments. Cairncross “shows that you don’t have to be flamboyant to achieve great influence,” wrote a former boss, “and that you do not have to be malicious to be interesting.”

“By some odd quirk of memory,” his biographers write, in his autobiography, A Life in the Century, Cairncross neglected to mention the Glasgow edition of the works of his fellow Scot that he commissioned, “although he himself had given the opening paper.” Yet that comprehensive record of the circumstances, and, at their center, the founding work – An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations – from which modern economics emerged may have been his single most durable accomplishment. Cairncross concluded his introductory address to the convocation this way:

“We are more conscious perhaps than Adam Smith of the need to see the market within a social framework and of the ways in which the state can usefully rig the market without destroying its thrust. We are certainly far more willing to concede a larger role for state activities of all kinds, But it is a nice question whether this is because we can lay claim, after two centuries, to a deeper insight in determining the forces determining the wealth of nations or whether more obvious forces have played the largest part: the spread of democratic ideals, increasing affluence, the growth of knowledge, and a centralizing technology that delivers us over to the bureaucrats.”

For an accounting of the lives among the bureaucrats of some distinguished present-day economists, see this column next week.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: What an economist and what a family!

Milton Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in 1976, but something more important to economics happened that year, and I don’t mean the bicentennial of the American Revolution. The Glasgow Edition of the Works of Adam Smith appeared that year as well, timed to commemorate the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations.

“Modern economics can be said to have begun with the discovery of the market,” began Sir Alexander Cairncross, Chancellor of the University of Glasgow, in his opening address to the convocation that introduced the new edition.

He continued:

“Although the term “market economy” had yet to be invented, its essential features have debated the strength and limitations of market forces [ever since] and have rejoiced in their superior understanding of these forces. The state, by contrast, needed no such discovery.”

Cultural entrepreneurs in economics, even the most effective among them, such as John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, do their work against the background of hard-earned knowledge of others, standing on the shoulders of giants and all that.

Eight beautiful volumes had rolled off the presses: two containing The Wealth of Nations; another with Smith’s first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments,; three more volumes of essays, on philosophical subjects (which includes the famous essay on the history of astronomy), jurisprudence, and rhetoric and belles letters; a collection of correspondence and some odds and ends; and, in the eighth, an index to them all.

Each contains introductions by top Smith scholars, with edifying asides tucked in among the footnotes. Two companion volumes accompanied the release, published by Oxford University Press: Essays on Adam Smith, and The Market and the State: Essays in Honor of Adam Smith, by way of penance. Smith had been educated at the University of Glasgow but scorned Oxford, where he spent six post-graduate years, mostly reading. Inexpensive volumes of any or all of the Glasgow edition can be had from the Liberty Fund.

A feast, in other words, for those interested in thinking about such things.

One such was Cairncross, whose Wikipedia entry begins this way:

“Sir Alexander Kirkland Cairncross KCMG FRSE FBA (11 February 1911 – 21 October 1998), known as Sir Alec Cairncross, was a British economist. He was the brother of the spy John Cairncross [worth reading!] and father of journalist Frances Cairncross and public health engineer and epidemiologist Sandy Cairncross.”

More to our point, for twenty-five years Cairncross was chancellor of Glasgow University (1971-1996). It was he who commissioned the Glasgow edition of Smith. He delivered the inaugural address I quoted above.

Before that, however, Cairncross became an economist, as an under graduate at Glasgow (where his namesake had been Chancellor three centuries before, then, beginning in 1932, at Trinity College, Cambridge, under John Maynard Keynes and his increasingly incensed rival, Dennis Robertson. Keynes published his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money to great excitement in 1936; Roberson steered Cairncross away from theory and into applied economics. After graduating with honors, he returned to Glasgow as a lecturer and wrote a textbook.

His service in government during World War Two and after was extensive and exemplary: the Ministry of Aircraft Production; Treasury representative at the Potsdam Conference; a stint at The Economist; advisor first to the Board of Trade, then to the Organization for European Economic Cooperation; ten years as Professor of Applied Economics at Glasgow; then, for another decade, various high-ranking positions in the Treasury. The appointment as Glasgow’s Chancellor came in 1971.

If you are interested in post-war Britain, particularly the Sixties, the Royal Academy’s biographical minute on Cairncross makes interesting reading. Quietly told in 1964 about his brother’s treachery as a paid agent of the KGB, he called it “perhaps the greatest shock I ever experienced.”

Cairncross was a Keynesian economist, his biographers say. He was critical of monetarism and dismissed the idea of a “natural” rate of unemployment as absurd. He considered that industrial planning, while necessary in wartime, was no model for peacetime governments. Cairncross “shows that you don’t have to be flamboyant to achieve great influence,” wrote a former boss, “and that you do not have to be malicious to be interesting.”

“By some odd quirk of memory,” his biographers write, in his autobiography, A Life in the Century, Cairncross neglected to mention the Glasgow edition of the works of his fellow Scot that he commissioned, “although he himself had given the opening paper.” Yet that comprehensive record of the circumstances, and, at their center, the founding work – An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations – from which modern economics emerged may have been his single most durable accomplishment. Cairncross concluded his introductory address to the convocation this way:

“We are more conscious perhaps than Adam Smith of the need to see the market within a social framework and of the ways in which the state can usefully rig the market without destroying its thrust. We are certainly far more willing to concede a larger role for state activities of all kinds, But it is a nice question whether this is because we can lay claim, after two centuries, to a deeper insight in determining the forces determining the wealth of nations or whether more obvious forces have played the largest part: the spread of democratic ideals, increasing affluence, the growth of knowledge, and a centralizing technology that delivers us over to the bureaucrats.”

For an accounting of the lives among the bureaucrats of some distinguished present-day economists, see EP next week.

Aerial view

“Skyway’’, by Sarah Giannobile, in her show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, March 1-30.

The gallery says:

“So much of that natural world that inspires Giannobile is from observing what is above. ‘Skyway,’ both the title of her exhibition and of one of the paintings in it (above), is a reference to birds and other winged creatures that inhabit that realm and whose abstracted forms frequently appear in her compositions.’’

The march of industry

”Samuel Slater Demonstrates the First Successful Textile Machinery,’’ in Pawtucket, R.I., circa 1793 (oil on board), by Adam Cl,ymer (1907-1989), from American Cyanamid corporate calendar 1968, at the National Museum of American Museum, Newport, R.I.

— Copyright National Museum of American Illustration

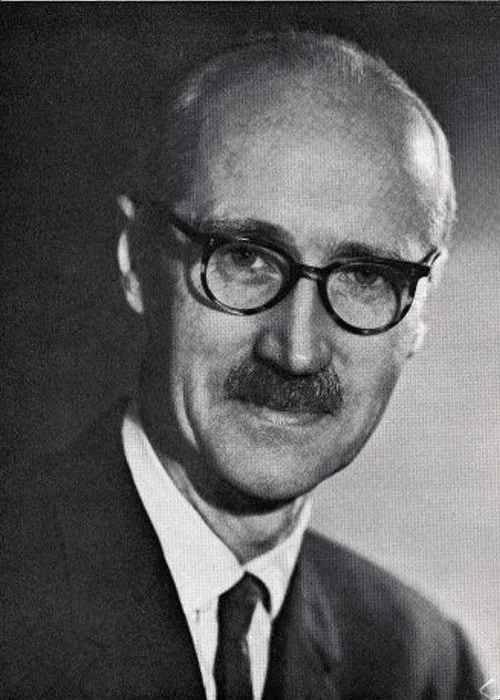

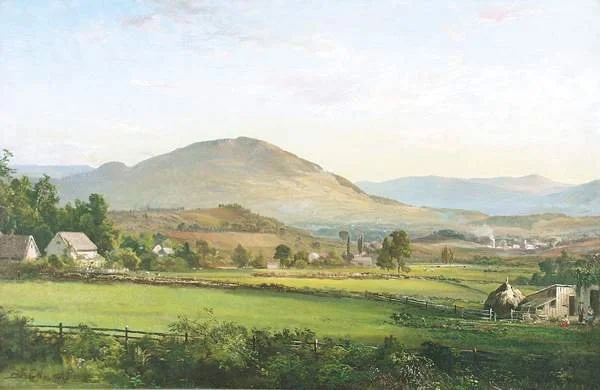

‘Its wholesome strength’

“View of Manchester, Vermont” (1870), by DeWitt Clinton Boutelle

“In Vermont, wherever you turn, you drink up beauty like rich milk, and feel its wholesome strength seep into your sinews.”

— Sarah N. Cleghorn (1876-1959), in Threescore: The Autobiography of Sarah N. Cleghorn (1936). A resident of Manchester, Vt., she was a poet, novelist and political activist.

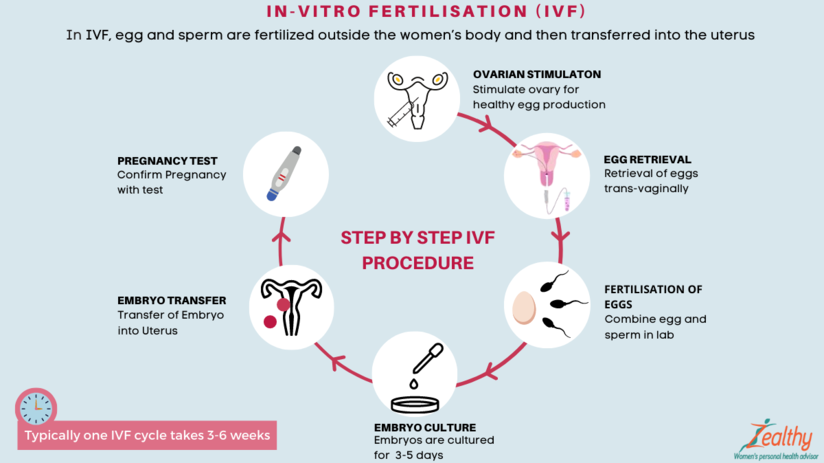

Michelle Andrews: Fertility treatment can be out of reach for the poor

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“This is really sort of standing out as a sore thumb in a nation that would like to claim that it cares for the less fortunate and it seeks to do anything it can for them.’’

— Eli Adashi, a professor of medical science at Brown University and former president of the Society for Reproductive Endocrinologists.

Mary Delgado’s first pregnancy went according to plan, but when she tried to get pregnant again seven years later, nothing happened. After 10 months, Delgado, now 34, and her partner, Joaquin Rodriguez, went to see an OB-GYN. Tests showed she had endometriosis, which was interfering with conception. Delgado’s only option, the doctor said, was in vitro fertilization.

“When she told me that, she broke me inside,” Delgado said, “because I knew it was so expensive.”

Delgado, who lives in New York City, is enrolled in Medicaid, the federal-state health program for low-income and disabled people. The roughly $20,000 price tag for a round of IVF would be a financial stretch for lots of people, but for someone on Medicaid — for which the maximum annual income for a two-person household in New York is just over $26,000 — the treatment can be unattainable.

Expansions of work-based insurance plans to cover fertility treatments, including free egg freezing and unlimited IVF cycles, are often touted by large companies as a boon for their employees. But people with lower incomes, often minorities, are more likely to be covered by Medicaid or skimpier commercial plans with no such coverage. That raises the question of whether medical assistance to create a family is only for the well-to-do or people with generous benefit packages.

“In American health care, they don’t want the poor people to reproduce,” Delgado said. She was caring full-time for their son, who was born with a rare genetic disorder that required several surgeries before he was 5. Her partner, who works for a company that maintains the city’s yellow cabs, has an individual plan through the state insurance marketplace, but it does not include fertility coverage.

Years after she had her first child, Joaquin , Mary Delgado found out that she had endometriosis and that IVF was her only option to get pregnant again. The news from her doctor “broke me inside,” Delgado says, “because I knew it was so expensive.” Delgado, who is on Medicaid, traveled more than 300 miles round trip for lower-cost IVF, and she and her partner, Joaquin Rodriguez, used savings they’d set aside for a home. Their daughter, Emiliana, is now almost a year old.

Some medical experts whose patients have faced these issues say they can understand why people in Delgado’s situation think the system is stacked against them.

“It feels a little like that,” said Elizabeth Ginsburg, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Harvard Medical School who is president-elect of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, a research and advocacy group.

Whether or not it’s intended, many say the inequity reflects poorly on the U.S.

“This is really sort of standing out as a sore thumb in a nation that would like to claim that it cares for the less fortunate and it seeks to do anything it can for them,” said Eli Adashi, a professor of medical science at Brown University and former president of the Society for Reproductive Endocrinologists.

Yet efforts to add coverage for fertility care to Medicaid face a lot of pushback, Ginsburg said.

Over the years, Barbara Collura, president and CEO of the advocacy group Resolve: The National Infertility Association, has heard many explanations for why it doesn’t make sense to cover fertility treatment for Medicaid recipients. Legislators have asked, “If they can’t pay for fertility treatment, do they have any idea how much it costs to raise a child?” she said.

“So right there, as a country we’re making judgments about who gets to have children,” Collura said.

The legacy of the eugenics movement of the early 20th century, when states passed laws that permitted poor, nonwhite, and disabled people to be sterilized against their will, lingers as well.

“As a reproductive justice person, I believe it’s a human right to have a child, and it’s a larger ethical issue to provide support,” said Regina Davis Moss, president and CEO of In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda, an advocacy group.

But such coverage decisions — especially when the health care safety net is involved — sometimes require difficult choices, because resources are limited.

Even if state Medicaid programs wanted to cover fertility treatment, for instance, they would have to weigh the benefit against investing in other types of care, including maternity care, said Kate McEvoy, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “There is a recognition about the primacy and urgency of maternity care,” she said.

Medicaid pays for about 40 percent of births in the United States. And since 2022, 46 states and the District of Columbia have elected to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months, up from 60 days.

Fertility problems are relatively common, affecting roughly 10% of women and men of childbearing age, according to the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Traditionally, a couple is considered infertile if they’ve been trying to get pregnant unsuccessfully for 12 months. Last year, the ASRM broadened the definition of infertility to incorporate would-be parents beyond heterosexual couples, including people who can’t get pregnant for medical, sexual, or other reasons, as well as those who need medical interventions such as donor eggs or sperm to get pregnant.

The World Health Organization defined infertility as a disease of the reproductive system characterized by failing to get pregnant after a year of unprotected intercourse. It terms the high cost of fertility treatment a major equity issue and has called for better policies and public financing to improve access.

No matter how the condition is defined, private health plans often decline to cover fertility treatments because they don’t consider them “medically necessary.” Twenty states and Washington, D.C., have laws requiring health plans to provide some fertility coverage, but those laws vary greatly and apply only to companies whose plans are regulated by the state.

In recent years, many companies have begun offering fertility treatment in a bid to recruit and retain top-notch talent. In 2023, 45 percent of companies with 500 or more workers covered IVF and/or drug therapy, according to the benefits consultant Mercer.

But that doesn’t help people on Medicaid. Only two states’ Medicaid programs provide any fertility treatment: New York covers some oral ovulation-enhancing medications, and Illinois covers costs for fertility preservation, to freeze the eggs or sperm of people who need medical treatment that will likely make them infertile, such as for cancer. Several other states also are considering adding fertility preservation services.

In Delgado’s case, Medicaid covered the tests to diagnose her endometriosis, but nothing more. She was searching the internet for fertility treatment options when she came upon a clinic group called CNY Fertility that seemed significantly less expensive than other clinics, and also offered in-house financing. Based in Syracuse, New York, the company has a handful of clinics in upstate New York cities and four other U.S. locations.

Though Delgado and her partner had to travel more than 300 miles round trip to Albany for the procedures, the savings made it worthwhile. They were able do an entire IVF cycle, including medications, egg retrieval, genetic testing, and transferring the egg to her uterus, for $14,000. To pay for it, they took $7,000 of the cash they’d been saving to buy a home and financed the other half through the fertility clinic.

She got pregnant on the first try, and their daughter, Emiliana, is now almost a year old.

Delgado doesn’t resent people with more resources or better insurance coverage, but she wishes the system were more equitable.

“I have a medical problem,” she said. “It’s not like I did IVF because I wanted to choose the gender.”

One reason CNY is less expensive than other clinics is simply that the privately owned company chooses to charge less, said William Kiltz, its vice president of marketing and business development. Since the company’s beginning in 1997, it has become a large practice with a large volume of IVF cycles, which helps keep prices low.

At this point, more than half its clients come from out of state, and many earn significantly less than a typical patient at another clinic. Twenty percent earn less than $50,000, and “we treat a good number who are on Medicaid,” Kiltz said.

Now that their son, Joaquin, is settled in a good school, Delgado has started working for an agency that provides home health services. After putting in 30 hours a week for 90 days, she’ll be eligible for health insurance.

Michelle Andrews: is a Kaiser Family Health News contributing writer.

andrews.khn@gmail.com, @mandrews110

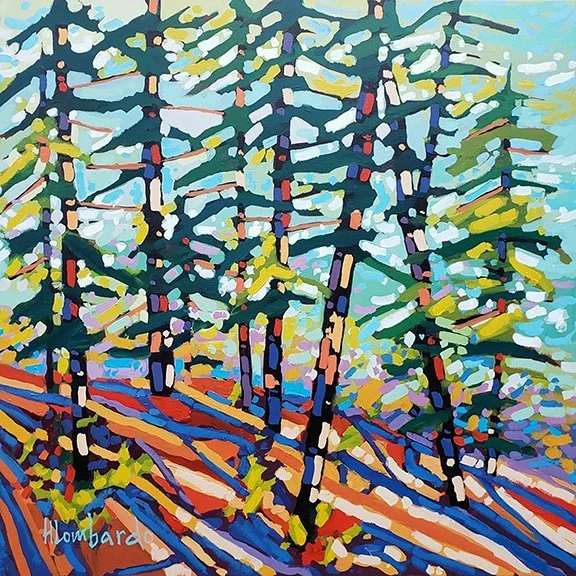

And light for us, too

“The Light Is for Me’’ (acrylic on canvas), by Holly Lombardo, at Bayview Gallery, Brunswick, Maine.

In Brunswick, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, where, between 1850 and 1852, she wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Chris Powell: Conn. uses electricity to hide cost of government

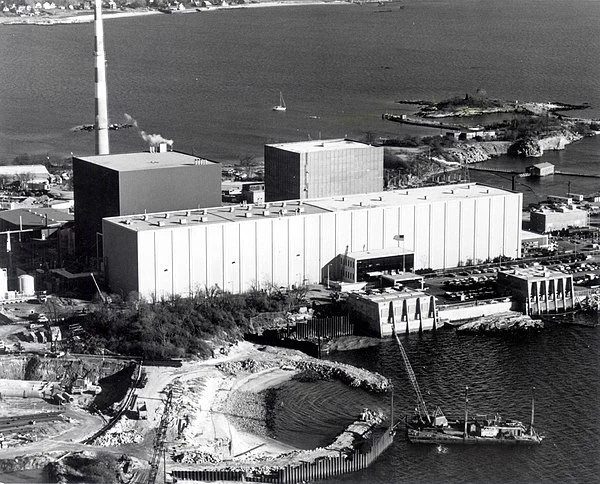

Millstone nuclear-power plant, in Waterford, Conn. State officials see the plant as vital to the state’s energy security.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Feeling unusually put-upon by state government, Connecticut's two major electric utility companies, Eversource and United Illuminating, are pushing back, which is good, since, whatever their faults, they are too easily demagogued against, as nearly everybody hates electric companies, electricity being too expensive.

Connecticut has the fourth-highest electricity costs in the country. But now the utilities, which formerly only grumbled privately about the biggest reason, are talking openly about it: government policy.

Ranking of state electricity costs.\

The forthcoming rate increases, expected to be around 19 percent, are reported to be entirely the result of two state government mandates.

The first mandate requires the utilities to purchase the production of the Millstone nuclear-power plant, in Waterford, electricity that sometimes is cheaper than other sources and sometimes isn't. State government has concluded that keeping Millstone operating is vital to Connecticut's energy security.

The second mandate requires the utilities to keep providing electricity to customers who consider themselves too poor to pay for it, whereupon that cost is transferred to customers who don't consider themselves too poor to pay and whose rates go up.

Quite apart from those mandates, Eversource long has estimated that 15-20 percent of its charges to customers arise from state mandates having little or nothing to do with the cost of the production or delivery of electricity.

Then there is the failure of Connecticut to import more natural gas, largely the result of New York's obstruction of new pipelines from the west

The co-chairman of the General Assembly's Energy and Technology Committee, Sen. Norm Needleman, D-Essex, accuses Eversource of trying to make customers pay for a cash-flow problem the company suffered as a result of its recent "wind-power investment gamble." But even there state government has to share responsibility. After all, why would electric companies "gamble" on wind power if government wasn't encouraging "green" energy and setting targets for accomplishing it?

The state government policies affecting electric rates are not necessarily wrong. But recovering their costs by hiding them in electricity bills, as Connecticut does, is dishonest. It deliberately misleads the public into thinking that the utilities are responsible for high rates when they are the work of government.

There is no social justice in requiring electricity users who pay their bills to pay as well for users who don't pay. The cost of people who don't pay their electric bills easily could be drawn against everyone from general taxation. Even the much bigger cost of subsidizing Millstone could be paid directly from general tax revenue.

Of course other taxes might have to be raised, but then people would see that it wasn't the big, bad utilities that took their money but that their own state legislators and governor did. Then people would be prompted to make a judgment on the policies behind the extra costs.

But hiding the cost of government in the cost of living is practically a principle of government in Connecticut. State taxes and the cost of state government policies are concealed not just in electricity rates but also in wholesale fuel taxes and medical and insurance bills so that energy companies, hospitals, doctors, and insurers take the blame, just as electric companies do.

Indeed, hiding the cost of government in the cost of living is now a primary principle of the federal government as well, with trillions of dollars in government expense being covered not by taxes but by borrowing, debt, the resulting money creation, and thus by inflation, which most people imagine is a force of nature, like the weather, something beyond human control.

Inflationary finance prevents people from asking their members of Congress inconvenient questions, such as how much more war in Ukraine, other stupid imperial wars, illegal immigration, Social Security, Medicare and new subsidy programs can we afford?

With their new candor about the origin of high electricity prices the utility companies are taking a big risk. Through the Public Utilities Control Authority, the governor and legislators can punish the companies expensively for telling the truth. But state government's deception of the public is already expensive.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Take a bright walk

Sunrise from the top of Cadillac Mountain, on Mt. Desert Island, Maine.

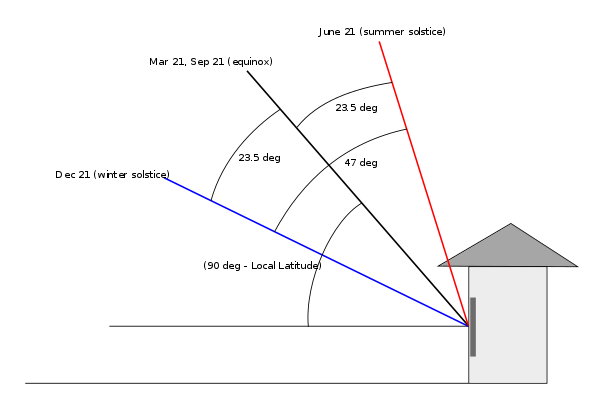

Seasonal differences in the Sun's declination, as viewed from New York City.

“Early Spring in New England” (1897), by Dwight William Tryon

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s good news for all who suffer from seasonal affective disorder. Solar spring began Feb. 5 and runs through May 4. It’s when daylight increases at the fastest pace during the year, gaining four hours and four minutes. This will gradually wake up plants, with such flowers as snowdrops blooming on south-facing slopes among the first you’ll see reacting. And wild animals will start getting more active, including that old recreation mating.

So no matter how dark world affairs may seem, there’s some hope to be found by walking around outside.

'Inhabitant of the Mind'

Amos Bronson Alcott created the reformist Temple School in Boston.

“I perceive that I am neither a planter of the backwoods, pioneer, nor settler there, but an inhabitant of the Mind, and given to friendship and ideas. The ancient society, the Old England of New England, Massachusetts for me.”

— Amos Bronson Alcott (1799-1888), teacher, writer and reformer and a member of the Transcendentalists group based in Concord, Mass., where he is buried in the famous Sleepy Hollow Cemetery with other intellectual luminaries of the time.

Llewellyn King: Political class is hiding between two old men; blame the primary system

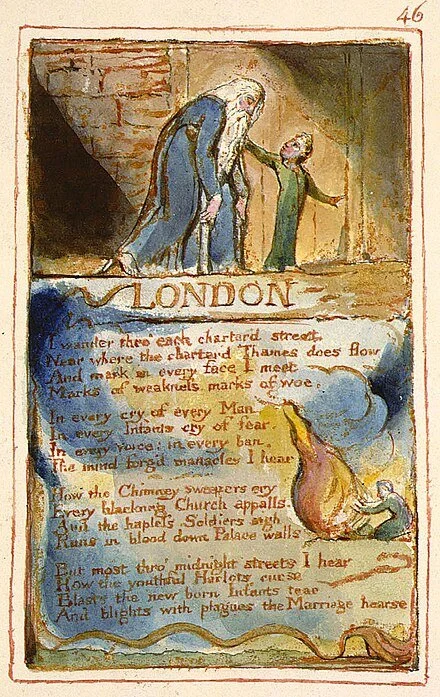

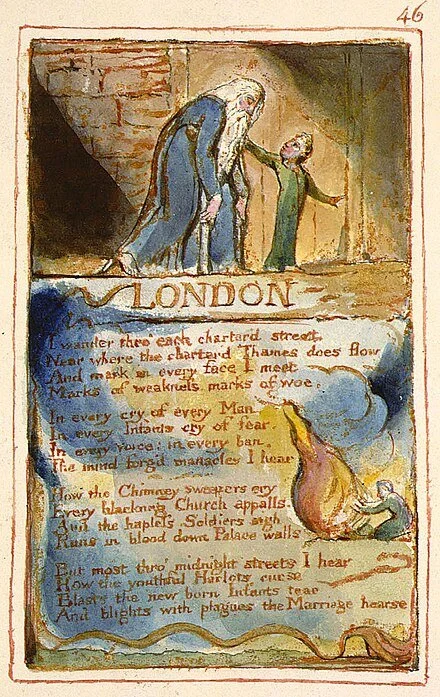

An image of an elderly man being guided by a young child accompanies William Blake's poem “London,’’ from his Songs of Innocence and Experience.

The Balsams Grand Resort Hotel, in Dixville Notch, N. H., the site of the first "midnight vote" in the New Hampshire primary.

— Photo by P199

WEST WARWICK, R.I.,

Even political junkies are feeling short of adrenaline. Two old men are stumbling toward November, spewing gaffes, garbled messages and misinformation as the political class cowers behind banners they don’t have the courage not to carry.

If you aren’t committed to Joe Biden or Donald Trump in a very fundamental way, it is a kind of torture — like being trapped in the bleachers during a long tennis match. The ball goes back and forth over the net, your head turns right, your head turns left. You watch CNN, turn to Fox, turn to MSNBC, turn back to CNN. You read The Washington Post, try The New York Times and then pick up The Wall Street Journal.

Over all hangs the terrible knowledge that this will end in a player winning who many think is unfit.

These two codgers are batting old ideas back and forth across the news. We know them too well. There is no magic here; nothing good is expected of either victory. Less bad is the goal, a hollow victory at best.

This is a replay. We can’t take comfort in the idea that the office will make the man. Rather, we feel this time, in either case, the office will unmake the man.

Both are too old to be expected to adequately deliver in the toughest job in the world. Much of the attention about age has focused on Biden, who recently turned 81, but Trump will be 78 in June and doesn’t appear to be in good health, and he delivers incomprehensible messages on social media and in public speeches.

We know what we would get from a Biden administration: more of the same but more liberal. His administration will lean toward the issues he has fought for — climate, abortion, equality, continuity.

From Trump, we know what we would get: upheaval, international dealignment, authoritarian inclinations at home, and a new era of chaotic America First. The courts will get more conservative judges, and political enemies will be punished. Trump has made it clear that vengeance is on his to-do list.

One candidate or the other, we are facing agendas that say “back to the future.”

But that isn’t the world that is unfolding. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the late, great Democratic senator from New York, said “the world is a dangerous place.”

Doubly so now, when engulfing war is a possibility, when there is an acute housing crisis at home, and when the next presidency will have to deal with the huge changes that will be brought about by artificial intelligence. These will be across the board, from education to defense, from automobiles to medicine, from the electric power supply to the upending of the arts.

How have we come to such a pass when two old men dodder to the finish line? The fact is few expect Biden to finish out his term in good physical health, and few expect Trump to finish his term in good mental health.

How did we get here? How has it happened that democracy has come to a point where it seems inadequate to the times?

The short answer is the primary system, or too much democracy at the wrong level.

The primary system isn’t working. It is throwing up the extreme and the incompetent; it is a way of supporting a label, not a candidate. If a candidate faces a primary, the issue will be narrowed to a single accusation bestowed by the opposition.

What makes for a strong democracy is representative government — deliberation, compromise, knowledge and national purpose.

The U.S. House is an example of the evil that the primary system has wrought. Or, to be exact, the fear that the primary system has engendered in members.

The specter of former Rep. Liz Cheney, a conservative with lineage who had the temerity to buck the House leadership, was cast out and then got “primaried” out of office altogether, haunts Congress.

No wonder the political class shelters behind the leaders of yesterday, men unprepared for tomorrow, as a new and very different era unfolds.

There is a sense in the nation that things will have to get worse before they get better. A troubled future awaits.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Breakfasts are best there

Pastel pictures by Ann Wickham, in pastels show at Long River Gallery, White River Junction, Vt., May 1-July 3.

Feds name Southeastern New England 'Ocean Tech Hub'

Central entrance at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth’s New Bedford campus.

— Photo by Ogandzyuk

Edited from a New England Council report

“Recently, the U.S. Economic Development Administration named Rhode Island and Southeastern New England as one of 31 Tech Hubs, calling it the ‘Ocean Tech Hub’. These Tech Hubs bring together public, private and academic partners into collaborative consortia to drive regional growth. The Ocean Tech Hub will focus on the autonomous systems industry and specialize in ocean robotics, sensors and materials in Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

“The hub also received a Tech Hubs Strategy Development Grant that will help the consortium increase local coordination and further manufacturing, commercialization and deployment efforts. About $500,000 of the grant funding is being put towards the hub’s ‘Grow Blue Initiative,’ which is working toward building the Southeastern New England economy through building a diverse and equitable industry to bolster commercial resilience, creating a diverse range of job opportunities, and utilizing internal and external partnerships.

“‘With big implications for climate adaptation and change mitigation, national security, and economic development, this opportunity impacts our startups, researchers, and workforce—and has implications for childcare, transportation, and housing needs,’ said Daniela Fairchild, the chief strategy officer at the quasi-public Rhode Island Commerce Corp.’’

Spring insurrection

Already blooming on south-facing slopes along the streets in Providence.