Seasonal seating

"Duality'' (oil on panel), by CINDY RIZZA, in the show "The Teeny Tiny Territory'' at the Bowersock Gallery, Provincetown, June 20-July 1. The group show presents art on small canvases.

Ah, the evanescence of lawn furniture, in the cellar most of the year, when not brought out for an over-subscribed kids' birthday party,

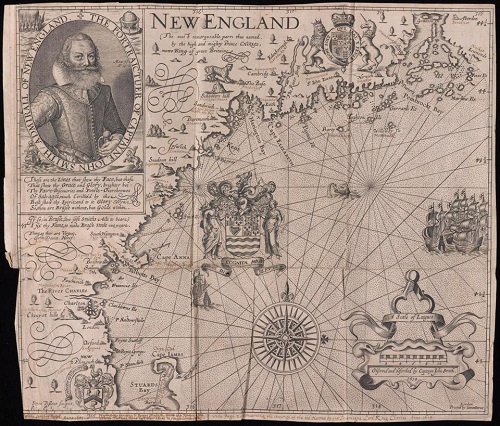

John Smith's 'virtual colonization' of 'New England'

John Smith's version of New England in his 1616 map,The map is in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, at Yale University, in New Haven.

Michael Blanding has written a delightful piece for the June 15 Boston Globe about English explorer/entrepreneur John Smith's fantastical map of New England, published in 1616 and based on Mr. Smith's expedition of 1614. The map was the first document to call the region "New England''. Other English place names were plunked in on the order of the then crown prince of England, Charles (as in the Charles River).

You'd never know from the map that most of the region was woods and that the settlements were Indian, with, of course, Indian names. But then, Mr. Smith apparently really did think that a freer, happier version of Olde England could be planted in "New England,'' and rather rapidly.

I (Whitcomb) love the scorpion tail of "Cape James'' (named after the English king of the time, James I, Charles's father) now known as Cape Cod.

As Mr. Blanding noted: {T}he scale of Smith's fictitious landscape was an unprecedented act of virtual colonization, drawn before a single permanent English settlement had been founded'' in New England.

But by associating the region so closely with England with these names, he helped draw the English here to take over. They were lucky, if that is the word, that a series of epidemics of diseases introduced into the region by European traders and sailors, probably operating mostly along the Maine coast, about the time of the map wiped out the majority of the Indians, whose settlements had quite different names than the Plimouth, etc., that Mr. Smith gave them to drum up business. The Indians had no immunity from these Eurasian diseases, which included smallpox.

Thus southern New England has a mixture of Indian and English place names.

Richard J. Eskow: What Democrats can learn from Cantor's defeat

Cartoon by KALIB BENDIB for OtherWords.org

David Brat, the man who unexpectedly defeated Eric Cantor in a recent Republican primary, is an ideologue. That should be a source of encouragement for candidates on the populist left — but not for the reasons that you might think.

Brat is a professor whose college chair is endowed with libertarian money and ran a campaign rife with Tea Party slogans. Yet it would be wrong to minimize Brat’s victory, as Hillary Clinton did, as solely the result of his across-the-board opposition to immigration reform. That theory deflects attention from the populist side of Brat’s campaign, thereby minimizing a movement that presents a potential threat to Clinton and a number of other Democrats.

Brat made Cantor’s Wall Street ties a key campaign theme by tapping into a frustration with corrupt Washington politics that spans the political spectrum. “I’m an economist. I’m pro-business. I’m pro-big business making profits,” Brat declared on the campaign trail. “But what I’m absolutely against is big business in bed with big government. And that’s the problem.”

It’s no wonder that reporter Ryan Lizza described Brat in The New Yorker as “the Elizabeth Warren of the right.” When Brat says “the Republican Party has been paying way too much attention to Wall Street and not enough attention to Main Street,” he echoes the Massachusetts senator’s theme that “the system is rigged for powerful interests and against working families” — and the argument that progressive Democrats are making about their party’s dominant wing.

That’s why Brat’s candidacy doesn’t belong in the standard Tea Party basket. Cantor more closely fit this mold, with his fiery Tea Party-like rhetoric belying the fact that he was very much part of the Beltway elite, a Republican apparatchik, and a friend of the corporate class.

When Brat called Cantor out — “the crooks up on Wall Street and some of the big banks…they didn’t go to jail. They are on Eric’s Rolodex” — the underdog garnered enough votes to win a race against a top dog.

His mix of messages comes as no a surprise to people such as me who track polling data on economic issues. It’s been clear for years that anti-corporate populism appeals to voters across the political spectrum.

Inside-the-Beltway consensus thinking tends to dismiss voices on both the left and the right as unimportant to the political process. The mythical “truly undecided centrist voter” — that legendary creature situated precisely halfway between the Republican and Democratic parties on key issues — has led the political class to ignore the electoral power of ideological voices.

Many Democrats are making the mistake of embracing the same pro-corporate positions as their Republican opponents while losing touch with what’s happening back at home.

Far-right media personalities, including Laura Ingraham and Mark Levin, gave Brat a tremendous leg up among conservative-populist true believers, stoking their enthusiasm and fueling both organizational efforts and turnout.

The left has its voices, too, and insurgent Democratic politicians shouldn’t be reluctant to rely on them just because they’re afraid that the “in crowd” in Washington will marginalize them. As Brat’s victory shows, distancing yourself from the in crowd can pay off.

Ideology has gotten a bad name from members of both parties who would rather push a Washington-corporate consensus than have a real debate on the issues and principles that should drive our nation’s decision-making.

What will happen if Republicans like Brat, with their anti-immigrant populism, face off against Democrats like Elizabeth Warren imbued with a populism grounded in economic justice? We might finally have a real debate about how to break the corporate stranglehold on politics and the economy.

Richard J. Eskow is a fellow at the Campaign for America’s Future and the host of "The Zero Hour'', a nationally syndicated radio show. He wrote this for OtherWords.org.

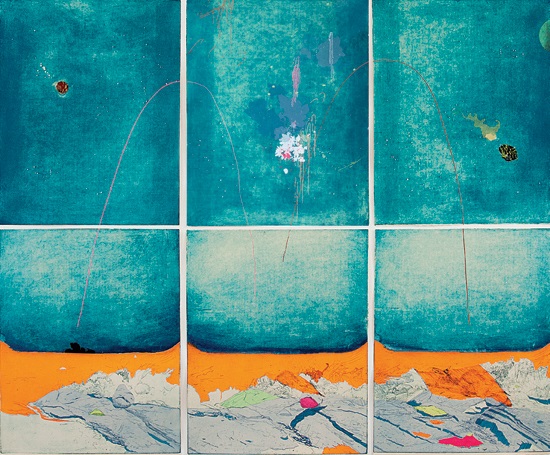

Dazed on the coast

"Later that Day at Second Beach'' (intaglio with chine colle, screenprint), by ALLISON BIANCO, in her show "The Baby Powder Trick'', at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, June 20-Aug. 2.

I saw some young mothers this morning taking their little kids swimming on one of our almost-officially-summer warm humid days. As I saw the kids scampering along, and the mothers following behind, already fatigued, the years peeled away and I was one of those kids seeing the summer spread out to beyond the horizon.

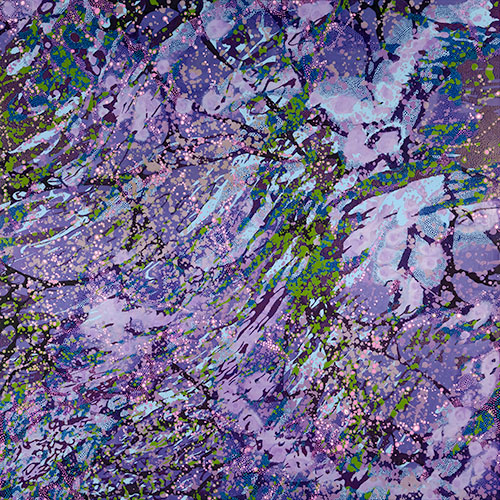

'Botanical archaeology'

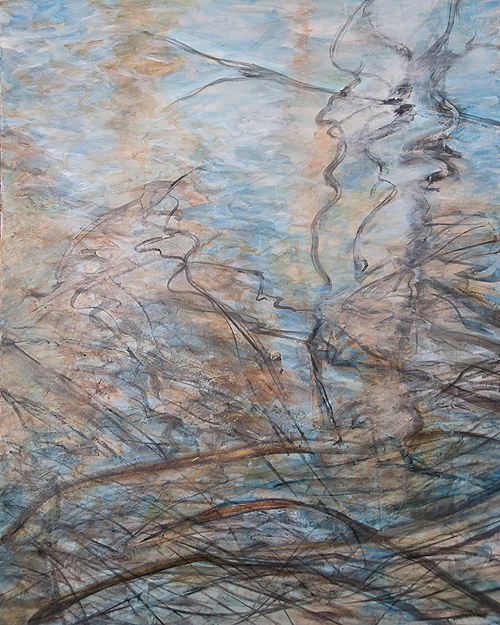

"Highway Into the Void'' (oil on canvas), by PETER WATTS, in his June 20-July 6 show at the Berta Walker Gallery, Provincetown.

The blurb for his show says that "he is always aware of the history of human touch that nature quickly covers over.'' The gallery calls his approach "botanical archeology.''

It said that Mr. Watts, who lives in Wellfleet, "sometimes paints houses based on his knowledge of local history coupled with discoveries like a long-abandoned cellar hole....A stand of pines on top of a knoll is a former pasture returned to seed, surrounded by the oak forests that will one day conquer it.''

Of course, much of New England, especially mostly densely populated southern New England, was once farmland. Despite the overall increase in the region's population, much of it has gone back to scrub or woods, leaving layers of ghosts.

The rise of "locavore'' agriculture, whose products are targeted at affluent suburbanites and urbanites, seems unlikely to return much of this land to open farmland, as popular as those farmers' markets, heavy laden with "organic'' produce, seem to be.

Through all this are what Mr. Watts sees as "nature's changing patterns and the patterns that repeat themselves.'' He said he used to be "more interested in the landscape itself. Now I look at how an abstract element of a landscape feels.''

This reminds me (Robert Whitcomb) of Alan Weisman's eerie coffee-table book The World Without Us, a nonfiction book about what the human-built environment might look like when humans disappear.

The weirdness of New Haven's Lincoln Oak

"Vigor Code,'' by JOE SLOMBA, in the "Nothing Is Set in Stone: The Lincoln Oak and the New Haven Green'' show, at the New Haven Museum, though Nov. 2.

"Vigor Code,'' by JOE SLOMBA, in the "Nothing Is Set in Stone: The Lincoln Oak and the New Haven Green'' show, at the New Haven Museum, though Nov. 2.

This is one of the strangest shows in a while.

As the museum puts it: The show combines ''contemporary art with archaeological analysis....''

"In October 2012, winds from Hurricane Sandy toppled the mighty oak — planted in 1909 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Lincoln's birth — revealing human skeletal remains in the tree's exposed roots and creating an enigmatic narrative that captured the imagination of the entire country.''

"Artists to be featured in the exhibition were invited to use branches, limbs or pieces of the trunk of the Lincoln Oak to interpret the history of the tree and the discoveries yielded beneath it. Zeb Esselstyn, renowned for his own work in transforming fallen trees into artistic and functional furniture, distributed the wood to the artists in February 2014....''

"Jeff Slomba {above} paid tribute to the fallen Lincoln Oak through his amalgamation of oak branch, steel, 3-D printed PLA plastic and sparklers. Slomba mused that the tree's destruction by Hurricane Sandy 'revealed not only the tree's own vulnerability, but also the mortality and slippage from history's memory of those who came before us.'''

''The scientific component of the exhibition consists of the results of the on-going archaeological analysis of human remains recovered from the site. Photo panels describe the remains ... and how they were used to determine the gender and approximate ages of those whose remains were unearthed in October 2012, and offer hypotheses on health and disease issues of the interred. The contents of two time capsules found at the site of the fallen Lincoln Oak are also on display.''

A desk with delight

"The Editor's Desk'' (installation: antique desk, chair, FujiColor prints, FujiFilm envelope, 35mm color film, archival gloves) by FORREST K. ELLIOTT, at the Patricia Ladd Carega Gallery, Center Sandwich, N.H.

In an age of cold, untactile digital art, the physicality of film and gloves is inviting. And while many people associate desks with grinding work, this one looks like a refuge, as is my (Whitcomb's) desk, safely positioned eight feet below ground level in our basement. I look almost straight up through the thick wire mesh at a rose bush hit by the afternoon sun. It's rather like being in a friendly prison.

Warm-blooded gun

Photo by JAMES J. ORAM, a Connecticut-based photographer specializing in black-and-white images that evoke a lot of moods, although chiefly something between mellowness and melancholy.

The possession of pit bulls in tough neighborhoods suggests that they're meant as signs of strength and protection -- a sort of warm-blooded gun. Mr. Oram has had much opportunity to see pit bulls in some of the gritty old factory towns of the Naugatuck River Valley, where he lives.

The Naugatuck, by the way, used to sport a variety of vivid colors from the industrial wastes of varying toxicity that were directly dumped into the river before the arrival of the Environmental Protection Agency. The pollutants would then flow down into Long Island Sound, where they would help kill fish and birds that they hadn't already been killed upriver.

Mr. Oram's Web site is here.

The wine-dark Acushnet

Here's a terrific essay by William Morgan, with great pictures, about the grand Greek Revival buildings put up in the 19th Century in and around whale-oil-rich New Bedford, which for a time was the richest community in America. The discovery of the many uses of petroleum ended that golden age for New Bedford (while constraining the nightmare of the whales -- highly intelligent mammals that the whalers consigned to excruciatingly painful deaths). See "Athens on the Acushnet''.

POBA the preservationist

''Deluca's Market'' (Provincetown), by NANCY WHORF (1930-2009), as seen in POBA -- Where The Arts Live,'' a new virtual art gallery "dedicated to preserving the works and creative legacies of exceptional artists whose talents were not fully recognized during their lifetimes.''

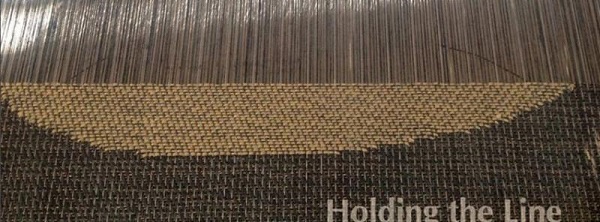

The aesthetics of thread

A nice tribute, in a way, to New England's textile industry is "Holding The Line,'' a show of fiber work at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth's College of Visual and Performing Arts through Sept. 11. The show's notes say that he work "captures a point of view, maintains a perspective, and defends a principle through the linear qualities of thread.''

A nice tribute, in a way, to New England's textile industry is "Holding The Line,'' a show of fiber work at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth's College of Visual and Performing Arts through Sept. 11. The show's notes say that he work "captures a point of view, maintains a perspective, and defends a principle through the linear qualities of thread.''

Sounds pretty windy. Still, there's real art here.