The multiplying uses of seaweed

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

When I was a kid living along Massachusetts Bay, we often saw seaweed (various species of marine macroalgae – kelp, etc.) as somewhat irritating. It could get in the way of fishing lines, and it would pile up on beaches in rank rows.

But seaweed, which, blessedly, grows rapidly, is looking better and better. It absorbs carbon dioxide, absorption that directly fights global warming, and it offsets a bit of ocean acidification caused by carbon dioxide from our fossil-fuel burning; it slows coastal erosion by weakening the force of waves in storms that have worsened as sea levels rise, and provides shelter for innumerable marine creatures. It’s used to make food, fertilizer, medicines, bioplastics, biofuel and animal feed.

(I’m sure that many readers have tried the seaweed salad in ethnic Asian restaurants.)

And now researchers are investigating its use as a source of minerals, such as platinum and rhodium, as well as “rare-earth” elements (which actually aren’t that rare), that are crucial in the renewable-energy sector and in other technological applications, too. Seaweed sucks up these minerals.

Much more research needs to be done to demonstrate all possible uses of seaweed, but the potential for seaweed aquaculture seems enormous. I can see many profitable new seaweed farms being developed off the southern New England coast. There’s already a large kelp-farming sector in the Gulf of Maine, benefiting from the size of available waters, and the industry is growing along the Rhode Island and Connecticut shoreline, too.

It’s heartening to see scientists working on all-natural ways to address global warming. Of course, in some places there will be fights over which sites to take over for seaweed farming; I hope that the broad public interest will usually win over, say, the demands of summer yachtsmen. Certainly, these farm sites should be chosen carefully, with guidance from the likes of the Marine Biological Laboratory, in the village of Woods Hole in Falmouth, Mass.

Hit these links and this one (video).

Islanders using everything they can from the sea

In this watercolor by William Hall, Block Islanders in the 19th Century are collecting fin fish, crabs and lobsters trapped in tidal pools. They also harvested large amounts of seaweed to be used for food and fertilizer. See photos below. This painting is part of an extensive series of watercolors Mr. Hall has done over the past decade of people at work.

He is represented by, among other venues, David Chatowsky Art Gallery, 47 Dodge St., Block Island, R.I. (401) 835-4623

One recipe for “seaweed pudding”:

Put a cup of dried seaweed in a pan and add a liter of whole milk.

Gently bring to boil and simmer for 10 to 15 minutes.

Strain through a fine sieve or a muslin cloth into a bowl and cool.

Put in a refrigerator to set for a couple of hours.

The harvesting of seaweed — mostly kelp — (including increasingly from aquaculture) for food and many other uses has greatly increased in the past few years. And seaweed aquaculture is more and more promoted for environmental reasons. For one thing, it absorbs some of the excess carbon dioxide put into the atmosphere by fossil-fuel burning. For another, seaweed — especially “kelp forests” — is a home for many species.

Collecting seaweed in locally made baskets.

Spreading seaweed as fertilizer on a Block Island farm.

Looking to build up the kelp crop

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Kudos to David Blaney, who’s starting the Point Judith Kelp Co., which, in a saltwater 2.75-acre farm, will grow a seaweed useful as a food, as fertilizer for land crops, for cosmetics and that absorbs nitrogen (which in large doses, such as runoff from lawns, can be a very bad pollutant) and carbon dioxide. In his project, he’s joining other local companies that are growing kelp.

There was a charming profile of Mr. Blaney in ecoRI News on Oct. 13. As man-made climate change warms coastal waters, some fish species will move away. It’s important that we find alternate crops that can thrive in southern New England waters. Mr. Blaney, ecoRI reports, thinks about the water eventually getting too warm for kelp. But such warmer-water plant species as Irish moss and sea lettuce are a hedge. As global warming proceeds, we’ll need all the diversification we can get.

To read the Blaney profile, please hit this link.

It’s such small enterprises that take advantage of Rhode Island’s location and other comparative advantages, that hold out hope for Rhode Island’s long-term prosperity as it tries to recover from its far too long dependence on old manufacturing industries and low-paid service jobs.

And now, seaweed as fuel

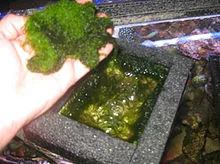

Seaweed being lifted out of top of algae scrubber/cultivator, to be discarded or used as food, fertilizer, or skin care.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

The green-energy revolution goes on: As GoLocal24 has reported, the U.S. Energy Department has awarded Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution researchers $5.7 million to advance technology leading to the mass production of sugar kelp, a seaweed, to make biofuels and bio-based chemicals.

The grants are from the Macroalgae Research Inspiring Novel Energy Resources (MARINER) Program (what a name!). A biologist with the group, Scott Lindell, told GoLocal: “Seaweed farming avoids the growing competition for fertile land, energy-intensive fertilizers, and freshwater resources associated with traditional agriculture.’’

Many readers may have eaten seaweed salad in an Asian restaurant; it’s delicious. Seaweed has some other uses, including cosmetics. It’s nice to know that New Englanders might soon grow it for food and fuel, anything to reduce our energy dependency on other regions.

Leigh Vincola: Eat your sea vegetables

Seaweed salad

Fifty years ago, Charlie Yarish was fishing on Long Island when he first took an interest in seaweed. Where the fishing was good, he found certain types of seaweed, and where it wasn’t so great, other types of seaweed gathered.

A spark was ignited for the young scientist, and Yarish took this excitement all the way to Dalhousie University in Halifax, where he was invited to participate in a three-month intensive field research program as an undergraduate. Yarish set out to answer all of his questions about this beautiful, diverse vegetation by growing it. Ultimately, the time he spent in Halifax change his life forever.

Today, decades of research and experimenting later, Yarish is known as the grandfather of the emerging sea vegetable farming industry in the United States. He is a professor of marine science at the University of Connecticut and runs a seaweed research lab out of the Stamford campus.

There’s really not a lot to argue about when it comes to seaweed farming. It’s good for the environment, good for human health and good for the fisheries economy.

Yarish recognized this early on and saw, that while scientifically possible, no large-scale seaweed production was happening in the United States the way it was in Asia. He set out to change that making it his goal to nurture East Coast kelp farmers by following an “open source” approach.

All new farmers have access to Yarish’s knowledge and research. In return, Yarish asks that each farmer make his or her products available to his research lab, so that he can continue to unravel the mysteries of seaweed and figure out the part it plays in marine biology.

Yarish puts it simply, “Sea vegetable farming has a great environmental benefit, while also providing a valuable commodity that is nutritionally beneficial.”

Environmentally friendly

Seaweed farming is as much about coastal resource management as anything, and the environmental benefits are central to Yarish’s work. As the co-chair of the Long Island Sound Study, Yarish showed that similar to shellfish, seaweed is a nutrient bioextractor, meaning that seaweed removes harmful nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon from the water.

Kelp farming also doesn’t require fresh water. When it comes to farming kelp, all that is needed is already there and the outcome is that the marine ecosystem is left healthier than how it was found.

Health benefits

The most common farmed kelp species in New England is the sugar kelp. Winged kelp and horsetail kelp are other species that are in experimental phase. These varieties — and all seaweeds — are high in the essential minerals, trace elements and vitamins that we often don’t get from our diets.

In fact, in the United States, much of the food that we eat is nutrient poor, and our health is suffering because of it. Sea vegetables concentrate the minerals from the seawater, making them some of the most nutritious plants on earth. Adding just a few grams of dried seaweed to your meal daily can have a huge impact on overall health.

Fisheries economy

There are those who believe the future of fishing is aquaculture. “Kelp farming is giving people from the fishing industry the opportunity to have new, viable careers,” Yarish said.

The technology of sea vegetable farming is rather simple. Reproductive plants are grown in a laboratory to the size of a pinhead and wrapped around a PVC spool. When they’ve reached the right size, the seeds are unraveled in the sea on long lines and set to grow for five to six months.

Harvest season is in the spring, and from there are several ways to get seaweed to market: fresh, frozen, dried and value added. Today, 14 farmers from New York to Maine have seized this opportunity and are operating under licenses from their own state. Yarish is connected to each of them.

“I pass on all knowledge to the new farmers and that is essential to the success of our industry,” he said.

One key farmer to Yarish is Bren Smith, owner of Thimble Island Ocean Farm and executive director of GreenWave in New Haven, Conn. As a lifelong commercial fisherman, Smith was looking for solutions to help an ancient industry that was failing him and became the face of Yarish’s research.

Smith developed what he calls 3D Ocean Farming, a farming model that includes seaweed and shellfish and addresses issues of the environment, health and the economy. At GreenWave, part of Smith’s mission is to help new kelp farmers. The Farm Startup and Farmer Apprentice Program provides assistance with finding grant money, permitting, training and essential gear. GreenWave also is creating restorative hatcheries, where seeds are produced for sea vegetable farming, and is building seafood hubs where farmers can process and produce foods for distribution.

GreenWave is one of a few locations in New England that owns a “kelp cutter,” a seaweed processing machine that Yarish helped bring to the United States from a Korean manufacturer. The kelp cutter has significantly improved the amount of time it takes to get sea vegetables to market, and is an essential piece of equipment for large-scale productivity.

Currently, many if not most of the kelp farmers in southern New England use the cutter at GreenWave, according to Yarish. Maine Fresh Sea Farm also has one. and Yarish’s goal is to “sprinkle the cutter all over the East Coast as the industry demands it.”

He said the infrastructure is there for a seaweed boom, and like many food trends much of its success lies in the hands of chefs. When chefs begin experimenting with sea vegetable flavors and pushing people’s pallets, mainstream enthusiasm will follow.

For instance, Providence chef Jason Timothy of Laughing Gorilla Catering has been experimenting with kelp from the Point Judith Kelp Co. this summer.

Yarish has had a full career but he’s not done yet. Now that the foundation has been laid and kelp farming is taking hold on the East Coast, he is busy looking 10 or 15 years ito the future and making plans for better protecting the planet’s ocean environments. Yarish’s attention has turned toward figuring out how seaweed and ocean biomass will be a solution to future energy problems.

Editor’s note: The author is a partner in Laughing Gorilla Catering.