Jim Hightower: Inflation -CEO's brag about their price gouging

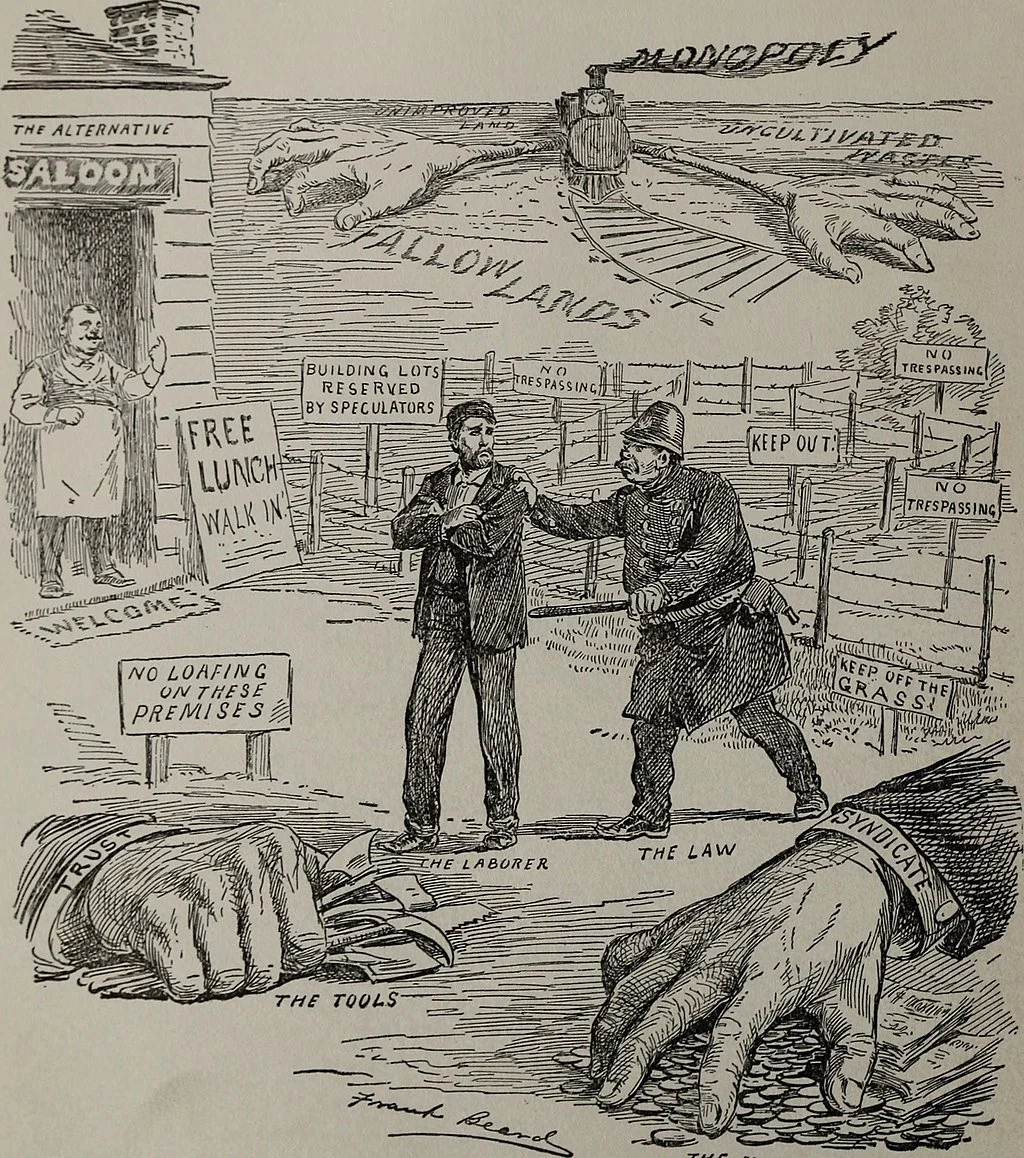

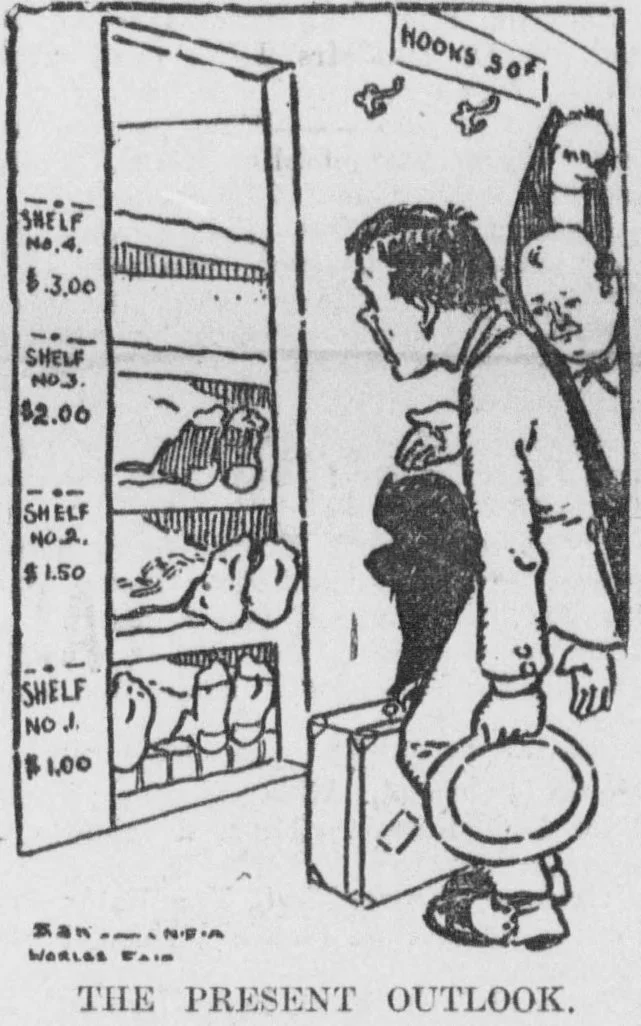

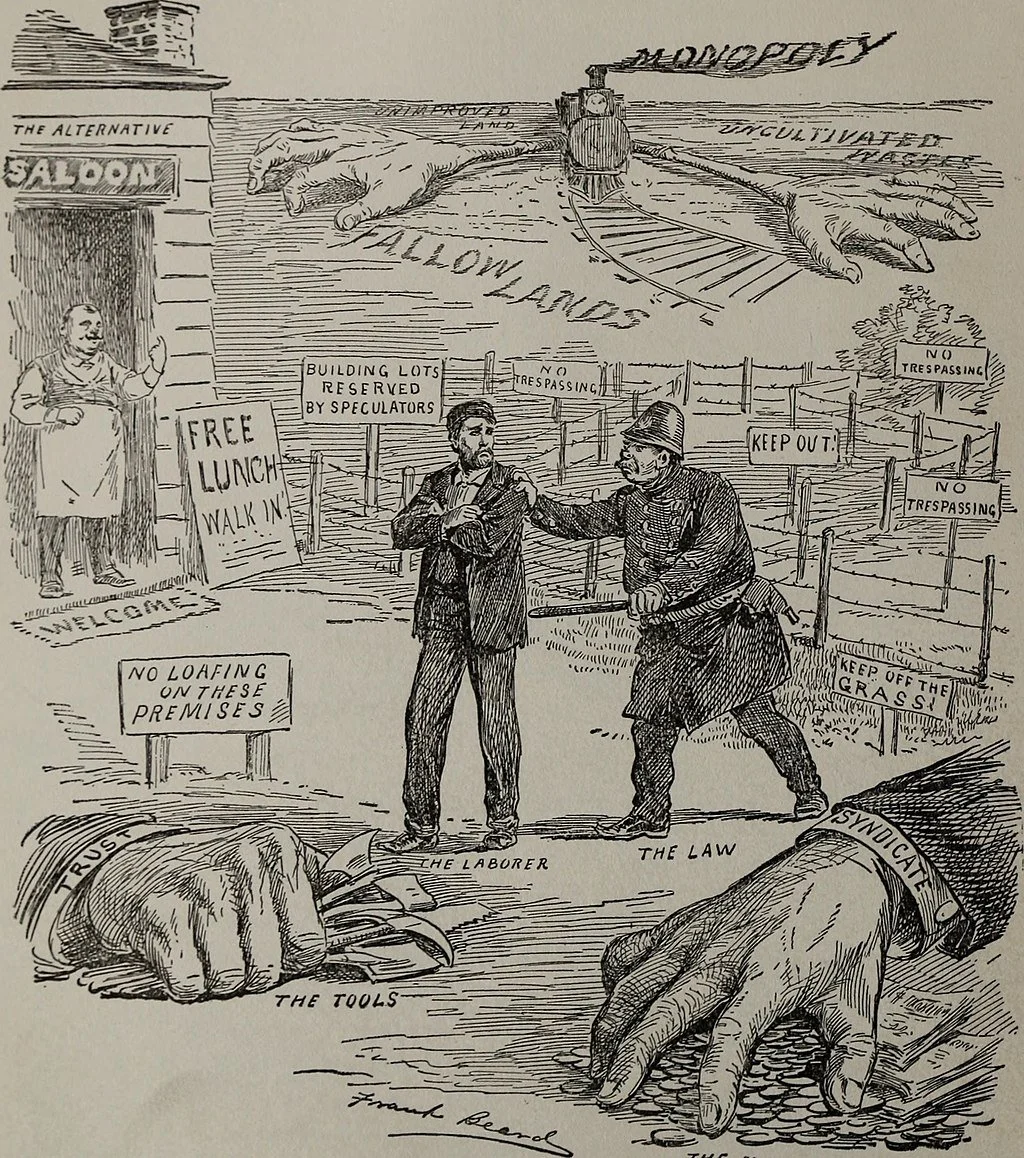

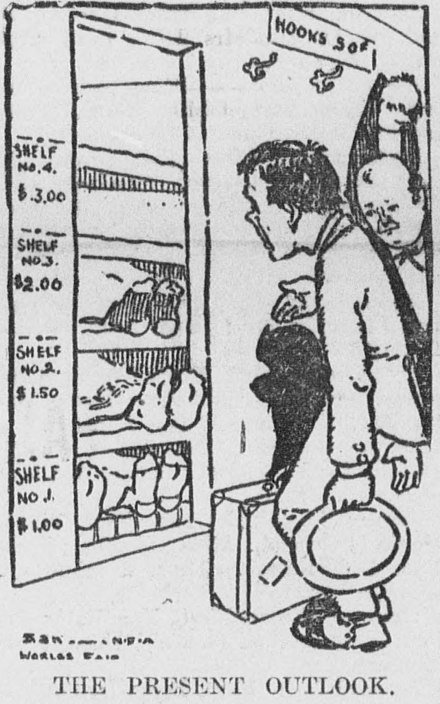

1904 cartoon warning attendees of the St. Louis World's Fair of hotel room price gouging.

Via OtherWords.org

Publicly, they moan that the pandemic is slamming their poor corporations with factory shutdowns, supply-chain delays, wage hikes and other increased costs. But inside their boardrooms, executives are high fiving each other and pocketing bonuses.

What’s going on? The trick is that these giants are in non-competitive markets operating as monopolies, so they can set prices, mug you and me, and scamper away with record profits.

In 2019 for example, before the pandemic, corporate behemoths hauled in roughly a trillion dollars in profit. In 2021, during the pandemic, they grabbed more than $1.7 trillion. This huge profit jump accounts for 60 percent of the inflation now slapping U.S. families!

Take supermarket goliath Kroger. Its CEO gloated last summer that “a little bit of inflation is always good in our business,” adding that “we’ve been very comfortable with our ability to pass on [price] increases” to consumers.

“Comfortable” indeed. Last year, Kroger used its monopoly pricing power to reap record profits. Then it spent $1.5 billion of those gains not to benefit consumers or workers, but to buy back its own stock — a scam that siphons profits to top executives and big shareholders.

Or take McDonald’s. It bragged to its shareholders that despite the supply disruptions of the pandemic and higher costs for meat and labor, its top executives had used the chain’s monopoly power in 2021 to hike prices, thus increasing corporate profits by a stunning 59 percent over the previous year.

And the game goes on: “We’re going to have the best growth we’ve ever had this year,” Wall Street banking titan Jamie Dimon exulted at the start of 2022.

Hocus Pocus. This is how the rich get richer and inequality “happens.”

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

1902 cartoon

David Warsh: 'Depreciation,' 'development' and 'inflation'

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Everyone knows that the cost of living has risen significantly in the past 75 years — recently, at rates not seen since the early ‘80s. To understand a little better why this has is happening, try this simple trick: Think of rising prices as a matter of the depreciation of the dollar against the prices of goods and services, instead of “inflation.” That won’t make the experience any less disorienting than calling it by the headline term, but it will give you a better sense of how and why the problem has arisen.

What’s the difference? With “inflation,” the answer is implied by the question. The explanation is always the same: the governors of the Federal Reserve Board have been cavalier with interest rates. Too much money is chasing too few goods. “Depreciation,” on the other hand, permits you to think about events taking place in the real world that forced the Fed’s hand – events that monetarists commonly describe as “ad hoc.”

Certainly a great deal of “ad hoc” change has occurred in the real world since 1950, when a candy bar cost a nickel and a haircut could be had for $1.25. Very little of the momentum behind that history would seem to have originated with the Fed, the stringent tightening of monetary policy in 1979-’82 being the major exception.

The current episode of rapidly rising prices is associated with the governmental response to COVID; accelerated with outbreak of all-out war in Ukraine; deglobalization of supply chains; food shortages and the threat of famine; policies designed to slow climate change, and energy disruptions now said to rival the crisis of the early and mid ‘70s.

True, in the course of regulating the nation’s system of money and banking, the Fed had to react to these various afflictions. Sometimes its governors may have overreacted. Sheer monetary incompetence can have a place in the story, too: Look no farther than the central bank of Sri Lanka for an example of that.

In the main, though, dollar depreciation occurs in response to real-world problems. Severe interest-rate policy can arrest expectations of runaway prices, as in the ‘80s. But dollar depreciation occurs in response to real forces. Never in millennia has it been reversed in a currency that endured. Repeating the mantra that “‘inflation’ is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon” is just blowing hot air.

In The Cost of Living in America: A Political History of Economic Statistics 1880-2000 (Cambridge, 2009), Thomas Stapleford, of the University of Notre Dame, describe how we came to employ sophisticated price indices to measure rising prices. The construction of economic statistics makes a fascinating story, but Stapleford spends only two paragraphs on why the cost of living changes, accepted at face-value explanations of particular episodes advanced by economists: W. Stanley Jevons, in the 19th Century, and Irving Fisher, in the 20th. In each case, the economists asserted, when “the supply of money increased, its value would fall, leading to higher prices.” Hence the “inflation” of prices by an excess of money.

But what if it works the other way around? What if the “cost-push” argument is more often correct? What if the quantity of money increases because prices are rising? Every central banker knows it is not simply one or the other; it is both. But with “inflation,” you only see one side of the story – in most instances, the less important side.

We don’t know more because there exists no conceptual scheme of sufficient generality to organize all those various “ad hoc” explanations of rising prices under one heading. Whatever intuitive appeal has existed in the term “complexity,’’ “complexity” was already well on its way to becoming a magic word, an incantation, quite devoid of meaning.

The second mistake I made was failing to notice that economists already possessed a serviceable term of their own to describe this dimension of modern life. They called it “economic development,” words as familiar and easy to use as they were lacking in precision. To give it meaning to development, as opposed to “growth,” which is a matter of inputs and output, requires only linking back to one of the most fundamental categories in all of economic theory: the division of labor.

Easier said than done! Although the role of specialization in producing material well-being is clearly spelled out in the first three chapters of An in Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith quickly moves on to the analysis of a competitive system, and this is the tradition, taken up by David Ricardo and T.R. Malthus, that has dominated economics down to the present day. I was slow to figure this out.

There! After fifty years of writing about these topics, often clumsily, my two key mistakes are acknowledged, and I have set out here all I have learned: “depreciation” and “development” (understood as the extent of the division of labor) are better language than “inflation,” not to mention (here I blush) “complexity” and “conflation” in 1984.

For a glimpse of how things might yet be different, and probably will be before long, see “One Analogy Can Hide Another: Physics and Biology in Alchian’s ‘Economic Natural Selection’”, by Clément Levallois, which ultimately appeared in 2009 in History of Political Economy. (JSTOR access required). Or tune in to Nathan Nunn, now back at the University of British Columbia. But the biological analogy at the heart of the re-launch of evolutionary economics in the years after World Wat II is too wonky for this column.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Seven Hills Park at Davis Square, Somerville. The towers in the park each represent one of the city's original hills.

Jim Hightower: Blame greedy corporate execs for surge in U.S. inflation

“The Worship of Mammon” (1909), by Evelyn De Morgan

Via OtherWords.org

Today, CEOs of big corporations are playing the tricky “Inflation Blame Game.”

Publicly, they moan that the pandemic is slamming their poor corporations with factory shutdowns, supply chain delays, wage hikes, and other increased costs. But inside their board rooms, executives are high fiving each other and pocketing bonuses.

What’s going on?

The trick is that these giants are in non-competitive markets operating as monopolies, so they can set prices, mug you and me, and scamper away with record profits. In 2019 for example, before the pandemic, corporate behemoths hauled in roughly a trillion dollars in profit. In 2021, during the pandemic, they grabbed more than $1.7 trillion.

This huge profit jump accounts for 60 percent of the inflation now slapping U.S. families!

Take supermarket goliath Kroger. Its CEO gloated last summer that “a little bit of inflation is always good in our business,” adding that “we’ve been very comfortable with our ability to pass on [price] increases” to consumers.

“Comfortable” indeed. Last year, Kroger used its monopoly pricing power to reap record profits. Then it spent $1.5 billion of those gains not to benefit consumers or workers, but to buy back its own stock — a scam that siphons profits to top executives and big shareholders.

Or take the fast-food purveyor McDonald’s. Executives bragged to their shareholders that despite the supply disruptions of the pandemic and higher costs for meat and labor, its top executives had used the chain’s monopoly power in 2021 to up prices, thus increasing corporate profits by a stunning 59 percent over the previous year.

And the game goes on: “We’re going to have the best growth we’ve ever had this year,” Wall Street banking titan Jamie Dimon exalted at the start of 2022.

Hocus Pocus — this is how the rich get richer and inequality “happens.”

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

David Warsh: Money follows development and vice versa

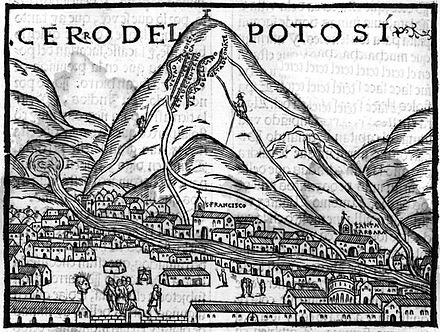

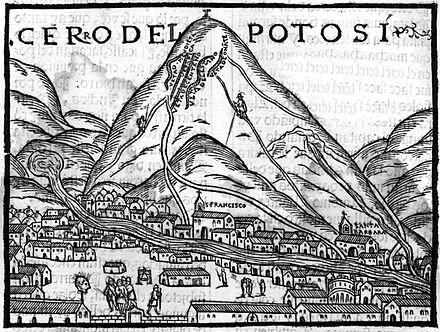

Cerro Rico del Potosi, the first European image, in 1553, of a silver-ore-rich mountain in what became Bolivia. It was heavily exploited by Spain.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A candy bar that cost a nickel in 1950 today costs $1.25 or so, depending on where you buy it. That, in a paper wrapper, is the price revolution of the 20th Century. Why did it happen? The answer usually given is that the quantity of money increased – too much paper money chasing too few candy bars.

A more satisfying explanation, casual though it may be, is to recognize that the global economy has grown considerably more complex since 1950, and the system of money, banking, and credit more complex along with it. The price of the candy bar wasn’t going to return to its previous level, no matter what the Fed or the candy-manufacturers did.

I’ve believed this for forty years, since writing The Idea of Economic Complexity, which appeared in 1984. While nothing has happened to change my mind, it has been interesting, at least to me, to have spent a few Saturdays thinking about what I have learned since then. Let me sum it up with a last few words of explanation, before putting it away.

At the moment, the jolt to increased economic complexity has to do with Russia’s war on Ukraine, the post-Cold War expansion of the NATO alliance and long-lasting disruptions of world trade stemming from the COVID pandemic. These “cost-push” factors are more fundamental to today’s rising prices, I believe, than whatever misjudgments that monetary authorities have made in responding to them. But arguing about recent events is the wrong way to develop views about phenomena as mysterious as the formation of money prices. For that, long-term developments serve best.

The price revolution of the 16th Century is the best example in the last thousand years of a lengthy, unreversed increase in money prices of everyday things. Its magnitude was modest by current standards; but then, so were monetary systems in those days. Between 1501 and 1650, prices of everyday goods across Europe rose six-fold before leveling off and remaining more or less stable on a new level for the next hundred years.

Practically from the beginning, scholars have argued about whether the discovery of the riches of Spanish America initiated the price revolution, or whether the voyages of discovery were undertaken in response to European events already underway. Jehan Cherruyt de Malenstroit blamed rising prices on shortages of precious metals and the extravagance of kings. In a widely read rejoinder, philosophe Jean Bodin, in 1568, ascribed rising prices to the influence of the treasure of The Americas – such was the beginning of what we have called ever since the quantity theory of money.

Economic historians were still arguing about these matters four centuries later. In American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, Earl Hamilton wrote, in 1934, that an “extremely close correlation” between growth in the volume of gold and silver imports from the New World and commodity prices in Spain “demonstrated beyond question” that the abundance of mines in New Spain was “the principal cause” of the price revolution. In Economic Development and the Price Level, in 1962, Geoffrey Maynard argued the opposite: that money generally adjusts to trade, rather than trade to money. In very different formats, the argument continues today.

“Development” is a bland word with which to describe the difference between the world economy in the time of Columbus and the world today. Economic philosopher David Ellerman has suggested that diversity describes the key difference, grounding his description in information theory; I proposed complexity in that 1984 book. But what is it that has become more diverse or complex? Not until I read “Increasing Returns an Economic Progress” (1928), by Allyn Young, did it occur to me that the growing complexity I had been thinking about were increases, of one sort or another, in the division of labor.

And there I left the subject behind. I was working for a magazine when I began writing about price history, complexity and plenitude, an exotic argument about the tacit assumptions of quantity theory of money, gleaned from reading Arthur O. Lovejoy’s The Great Chain of Being (1936). Magazines are lightweight vessels, quick to maneuver in pursuit of advantage, quick to move on. There was no way I could continue to write about economics.

Fortunately, I made my way to a serious newspaper. I finished the book I had begun, and soon put complexity behind me – until this spring, when I briefly took it out to re-examine it. Meanwhile, I had become an economic journalist, following the profession. I stumble on developments in growth theory, and these, too, eventually became a book, Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (2006).

So what have I learned? That journalism is about knowing, whereas economics is about proving. A great deal more truth can become known than can be proved, as physicist Richard Feynman once said. Complexity of the division of labor is still out there. Economists will get to it someday. See, for example, Hendrick Houthakker, “Economics and Biology: Specialization and Speciation” (1955). In the meantime, there are other important stories, happening now.

In case you are feeling unsatisfied, though, remember that five-cent candy bar. Are you comfortable with the too-much-money-chasing-too-few-goods story? Do you believe that the Fed could have prevented the rise in its price? And if wasn’t “inflation,” then what was it? The depreciation of money, relative to goods?

As with the 16th Century voyages of discovery, money follows development and development follows money. If you have only the quantity theory of money to rely on, you don’t know what is going on.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Trying to figure out how to measure ‘inflation’

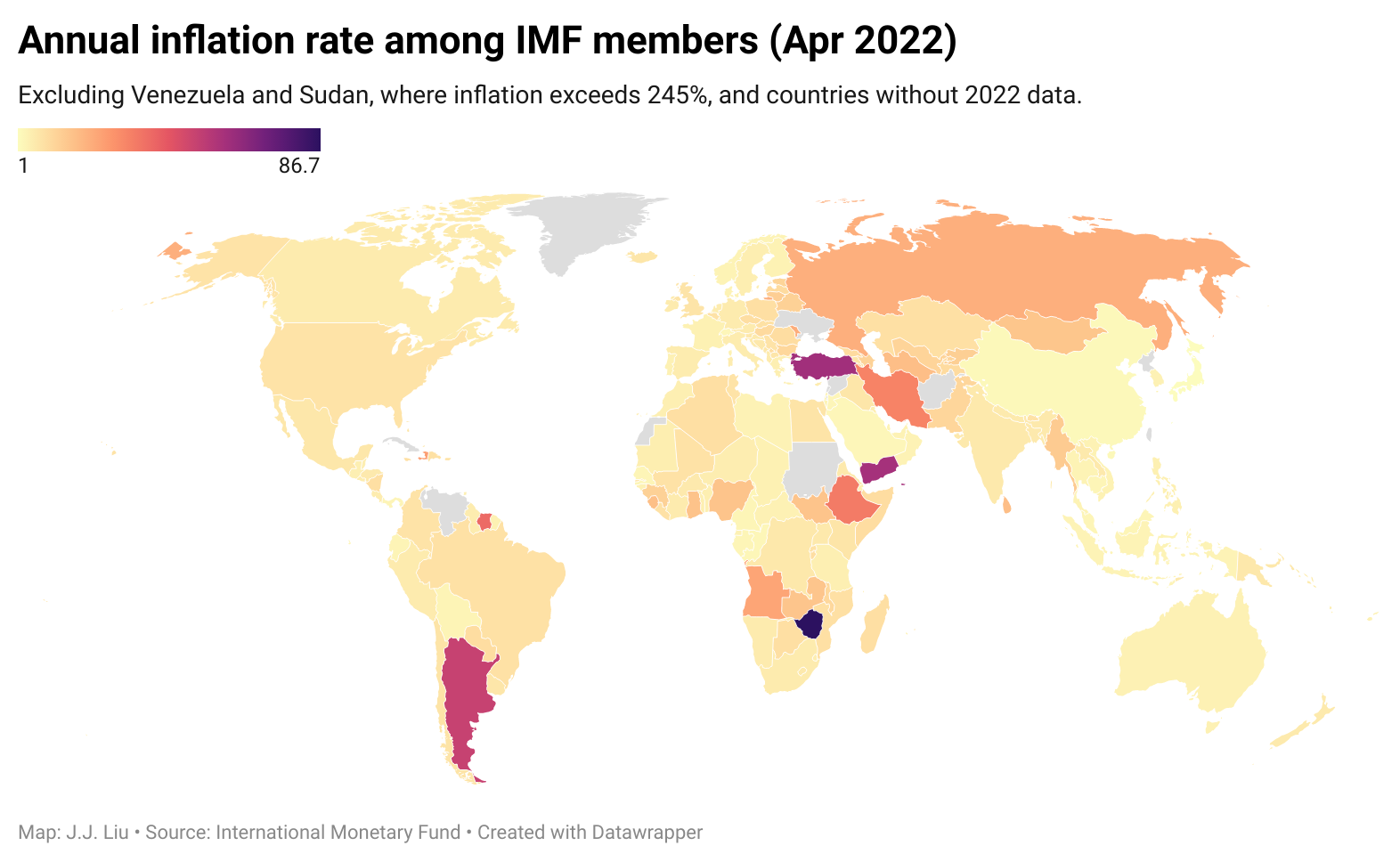

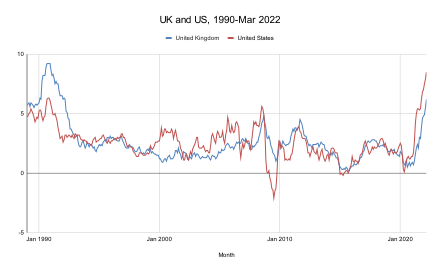

British and U.S. monthly inflation rates from January 1990 to February 2022.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

President Biden calls it Putin’s inflation. Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell says the problem began with the pandemic. Harvard University economist Lawrence Summers blames the Fed. Who’s right? Some 250 years of interplay between the science of pneumatics and its technological applications were the background against which economist Irving Fisher, in 1928, expanded the modern usage of the term “inflation” to mean something more than rising prices. Fisher is not a bad place to begin to look for an answer.

Arguments about whether or not such a thing as a vacuum can exist; quicksilver (meaning mercury); barometers; j-tubes; air pumps; valves, cylinders, and plungers; hot air balloons; footballs; the discovery of inert gases (starting with helium); the manufacture of incandescent light bulbs; pressure cookers; inflatable tires – these topics or objects became familiar before Fisher took advantage of relationships among pressure, volume, and temperature of gases, itself by then vaguely understood, in order to attach a new meaning to an old word.

“Anyone… reading [The Money Illusion] (Adelphi, 1928) by Fisher, or other books on monetary affairs published in this period, may have some difficulty with terminology” wrote Fisher’s biographer, Robert Loring Allen, many years after the fact. “For more than a generation, the words ‘inflation’ or ‘deflation’ [had] usually meant increasing or decreasing prices.” But in The Money Illusion. Allen wrote, Fisher coined new meanings: “the words inflation and deflation refer to the money supply, not to prices. Money inflates and in consequence prices rise and a deflation in the money supply causes falling prices.”

It was the first and only book about the subject that Fisher, a prominent Yale University professor and tireless reformer, would write for the general public. He was at pains to explain what he meant.

As I write, your dollar is worth about 70 cents. This means 70 cents of pre-war buying power. In other words, 70 cents would buy as much of all commodities in 1913 as 100 cents will buy at present. Your dollar now is not the dollar you knew before the War. The dollar always seems to be the same but it is changing. It is unstable. So are the British pound, the French franc, the Italian lira, the German mark, and every other unit of money. Important problems grow out of this great fact – that units of money are not stable in buying power.

A new interest in these problems has been aroused by the recent upheaval in prices caused by the World War. This interest nevertheless is still confined largely to a few special students of economic conditions, while the general public scarcely yet know that such questions exist.

Why this oversight?.. It is because of “the Money Illusion”; that is, the failure to perceive that the dollar, or any other unit of money, expands or shrinks in value. We simply take it for granted that “a dollar is a dollar” –that “a franc is a franc” that all money is stable, just as centuries ago, before Copernicus, people took it for granted that that the earth was stationary, that there was really such a fact as a sunrise or a sunset. We know now that sunrise and sunset are illusions produced by the rotation of the earth around its axis, and yet we still speak of, and even think of, the sun rising and setting!

Fisher is at pains to illustrate the illusion. He visits Germany with an economist friend, where the two interview 24 men and women. Only one considered that rising prices have anything to do with the government’s management of its currency.

They tried to explain it by ‘supply and demand’ of other goods, by the blockade; by the the destruction wrought by the War; by the American hoard of gold; by all manner of other things – exactly as in America when, a few years ago, we talked about “the high cost of living,” we seldom heard anybody say that a change in the dollar had anything to do with it.

Fisher went on to explain the system of gold, paper money, and bank “deposit currency,” as bank credit was known at the time. He noted that the Federal Reserve System had recently taken responsibility for the oversight of the money supply that occurred via the purchase and sale of government bonds by its Open Market Committee. He noted the suspension of the international gold standard during the World War and recommended its early resumption. Above all, he urged the adoption of price indices, carefully collected by government agencies, with which to measure changes in “the cost of living,” or, as he puts it, “fluctuations in the value of money.”

But the year was 1928. A world-wide boom was on. Fisher was already somewhat isolated from his university colleagues by his enthusiasm for business (he had sold his Rolodex card-filing system to Remington Rand Corp. and was trading millions in stocks). When the Depression began, instead of hedging his bets, he pursued business as usual a little while longer, and gradually lost his entire fortune. Meanwhile, economists turned their attention to John Maynard Keynes.

“It was particularly unfortunate,” Robert Dimand, of Brock University, has written, “that Fisher lost the attention of the economics profession, the public, and even his Yale colleagues just when he has something interesting to say about with what had gone wrong with his predictions and the economy,” to wit his article “The Debt-deflation Theory of the Great Depression” in the first volume of Econometrica, in lieu of an Econometric Society presidential address. He died in 1947.

But Fisher’s espousal of the value of index numbers to monitor variations in purchasing power stuck, as did his enthusiasm for the monetary, as opposed to real, explanation of rising prices. In Monetary Illusion, Fisher never mention Boyle; he offers a more homely analogy instead: “If more money pays for the same good, their price must rise, just as if more butter is spread over the same slice of bread, it must be spread thicker, the thickness representing the price level, the bread the quantDity of goods.” Twenty five years later, though, a master expositor of Keynesian economics, George Shackle, of Liverpool University, wrote,

How did we come to adopt the portentous word “inflation” to mean no more than a general rise in prices? I think this usage must have had its origin in a particular theory of the mechanism or cause of such a rise. When a given weight of gas is released from a steel cylinder into a large silk envelope, there may appear to be more gas, but in important senses, the amount of gas is unchanged. In a somewhat analogous way, we can make our total stock of currency spread over a larger number of paper notes, but this action in itself will not increase the size of the basket of goods (where various good are present in fixed proportion) that this total stock of currency would exchange for in the market…. Some such image as this may perhaps have been n the mind of the man, who first spoke of inflating the currency. This idea, that the general price level is closely related to the ostensible, apparent size of the money stock… has become formally enshrined in what is called the Quantity Theory of Money.

It’s been nearly 40 years since I published The Idea of Economic Complexity. What have I learned, in all the years since, about explaining generally rising prices? At least this: By all means let us continue to measure money and talk pneumatics. In hopes of narrowing differences of opinion, though, let us keep looking for something real and general in the economy to measure as well. I expect that the Fed has made a pretty good beginning on that.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: Inflation: Cost push or too much money?

U.S. inflation 1910-2018.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

From the beginning, the thing that puzzled me was the way the experts talked past each other, or, more frequently, didn’t talk at all.

I explained last autumn how a magazine assignment in 1975 immersed me in the ‘70s debate about inflation and led me to 700-year index of wages and prices in England. An unreversed “price revolution” in the sixteenth century was its central feature. Immediately I had turned to rival experts on the period, both emeritus professors at the University of Chicago. As I wrote in November,

It turned out that the facts of the price revolution were well-established, and had been understood in a certain way since Jean Bodin, in 1556, first pointed to the influx of New World gold and silver.

Earl J. Hamilton (1899-1989) published “American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501-1650’’; John Nef (1899-1988) had produced “The Rise of the British Coal industry’’, “Industry and Government in France and England 1540-1640,’’ and “War and Human Progress: an essay on the rise of industrial civilization.’’

Here were champions on opposing sides of the long-running argument about the price revolution. Some years later I learned that Joseph Schumpeter in his monumental History of Economic Analysis had characterized the difference of approach as between monetary and real analysis. I was dimly aware the gulf existed because I had began learning economics by reading two little books published in the 1920s, before John Maynard Keynes entered the debate: Money, by Sir Dennis Robertson, and Supply and Demand, by Hubert Henderson.

Schumpeter’s dichotomy was comforting because it periodized the controversy. Monetary analysis had thrived in the 17 and early 18th centuries, he had written; then, starting with Adam Smith, real analysis of supply and demand had eclipsed money for well over a century.

By 1975, the argument had again become front-page news. Inflation was surging. Why? Was the Federal Reserve Board imprudent in its conduct of monetary policy? Or were “cost-push” factors, OPEC price hikes and costs of its America’s Great Society and its Vietnam War forcing the hand of the Fed?

Alas, neither Hamilton nor Nef were of much use in writing about the issue in the present day. Both men had been born in 1899. Hamilton was a member of the university’s famous department of economics; Nef, a cultural historian. Only later did I come to understand what was implied by the distinction.

Hamilton had definitely won whatever debate existed between the two. As his department colleague Donald McCloskey wrote a few years later, “Various attempts to revise his history of prices (attaching it to population, for instance) have had difficulties with the sheer mass of evidence that Hamilton had accumulated, Kepler-like.”

Nef, orphaned son of a beloved Chicago professor, ward of another, married a pineapple heiress, and had gone on to write The Conquest of the Material World, in 1964, and, in 1973, a very beguiling The Search for Meaning: autobiography of a non-conformist.

More to the point, though, professional economics had moved on, dramatically. A new Nobel Prize in Economics had been established, first awarded in 1969. Paul Samuelson, a Keynesian (that being the new name that real analysis had acquired), had won the prize its second year, for “raising the general analytical and methodological level in economic science.”

And in 1976, Milton Friedman was recognized “for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history, and theory; and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy” – that is, for monetary analysis.

I wrote a Forbes cover story, in March 1975, taking note of the unreversed nature of 17th Century price explosion, venturing that it seemed unlikely that deflation, if it occurred, would return price levels to those that prevailed at the beginning of the 20th Century.

Like most journalists untrained in economics, I was partial to the cost-push explanation. Those OPEC price increases weighed heavy in the balance, it seemed to me. Moreover, the mid-’70s saw the beginning to the tax revolt: maybe the unmistakable growth of government since the ‘30s had something to do with it: There were new social programs, nuclear weapons, and rockets to the moon.

Reflecting on the similarities between the 16th and the 20th centuries, I was more intrigued by the emphasis the historian Nef had placed on developments in industry, government, and warfare, than by the changes in the quantity of money that had inarguably taken place, new world treasure then, and central banking now.

Mainly I was struck by the extent to which monetary analysis simply ignored the developments in the real sector that so interested Nef. Instead, monetarists (we were beginning to call them that) pursued their interests in money with apparently no thought for developments “on the ground” and banking. As for Hamilton, I thought of Albert Einstein rather than Johannes Kepler: Einstein had famously asserted, “It is the theory which decides what we can observe.” I had only just begun to read Milton Friedman’s work.

What was needed, I thought, was a theory real events of generality equal to that of the quantity theory, one which that might somehow cover all the ad hoc explanations usually advanced to explain rising prices. Together with a colleague, Lawrence Minard, I persuaded the Forbes editor, James Michaels, to let us prepare a longer piece to say as much. “Growing crops don’t make the sun shine” was a phrase we bandied about freely in those days.

It took some time. Not until other November 1976, a month after Friedman’s recognition was announced, did our lengthy article appear, under the headline “Inflation Is Now Too Important to Leave to the Economists.” A line from a Clark Gable film served as the article’s MacGuffin: “What do you mean they can’t pay more taxes? Tell them to put up the price of beans!” I wince now to see the headline in print, but the story won a Loeb award the next year, and Minard’s career and mine were launched.

There were parts of the argument that first piece made that Minard and I didn’t like. The tax angle was too acute; other angles we had come up with were missing. I persisted; Michaels remained receptive: ten months later Part Two appeared: “The Great Hamburger Paradox: An investigation into how economics went astray” (Wince again)!

This time I was “the author.” The MacGuffin was the contrast between a heavily-staffed an extensively-decorated restaurant with a fancy menu and a hamburger stand. That distinction conveyed well enough the difference between the 16th Century, when an ordinary householder was fortunate to possess a bowl and a spoon, and the 20th. The paradox was the way the labor cost of a hamburger had plummeted over centuries during which its money price continued to rise. This was a proposition about the importance of real factors: I ignored economists’ highly developed framework of supply and demand and conjured a nascent theory of “economic complexity,” employing an intuitively appealing but analytically empty word to connote the difference between degrees of development.

In terms of a restaurant menu, I wrote, the problem might be better understood as the bundling together of various costs, conflation of many costs, rather than the inflation of single price. Wordplay! This was very far from economics, and it wasn’t history, either. It was economic journalism, pure and very simple.

Then came the supply-siders, the “Mundell-Laffer hypothesis” and all that, with their emphasis on tax cuts and their preoccupation with economic growth, which they called an increase of “aggregate supply.” The influence of Steve Forbes, a future presidential candidate, grew at the magazine that his grandfather had founded and his father ran. After I was unable to get a story about James Buchanan, a future Nobel laureate, onto the magazine’s story list, I left for the library and the newspaper business. I had begun to specialize, and for the next forty years, I grew more interested in the economics profession and closer to it with every passing year.

All this came back recently as I browed through A Financial History of Western Europe, by Charles Kindleberger, in connection with another matter. I came across a section on the price revolution. It turns out that prices may have been rising in Europe for decades before the voyages of discovery got underway. The mines of central Europe yielded relatively little gold; silver was draining off to pay for spices imported on camels from the East; Henry the Navigator’s Portuguese sailors were able to sail south to the gold coast of Africa thanks to the invention of fore-and-aft rigging of sails, the stern rudderpost, and the compass; and that Columbus had been sent into the unknown in search of gold. (His diary mentions it 65 times in a voyage of less than a hundred days.) Kindleberger wrote,

Since [Earl] Hamilton’s book came out in 1934, something of a question has arisen whether the discovery of South America produced a price revolution de novo or whether it merely supported one already underway. The argument is a familiar one that we still encounter a number of times – in the debate between the banking and currency schools in nineteenth century England; between those who blame the first Great Depression represented by the fall in prices between 1873 and 1896 on the slowdown of the rate of increase in gold stocks and demonetization of silver, and those who ascribe it to real factors; and again in the explanation of the German inflation after World War I, held by monetarists to be due to simple over-production of money, and by their opponents to a complex set of real factors, including reparations, restocking, speculation, and the like….

The main a priori attack on the price revolution rests on the belief that, apart from the short run when money may be inelastic and halt a boom, money adjusts to trade rather than trade to money as the quantity theory would have it. .. If a clear-cut choice must be made between real factors and the quantity theory of money, this goes to the heart of the issue. But both explanations can be right and leapfrog one another. the bullion famine of the fifteenth century led to a frantic search for money’ the discovery of copious quantities of silver, plus debasement, and perhaps dishoarding and the coinage of plate, supported and extended the price rise which would otherwise had to reverse itself or lead to the development of money substitutes, as happened later. Clearly silver and war leapfrogged, and war is one of the greatest strains of resources and contributors to inflation.

I read the passage twice. Kindleberger’s compression of real and monetary explanations forcefully reminded me of the single most important lesson I had learned from covering professional economics in the fifty years since I wrote those adolescent articles for Forbes.

That clear-cut choice doesn’t have to be made, at least not when considered in the context of the sweet fullness of science and time. It is enough to expect that young economists will continue to do their work. “Inflation,” if that is what it is, is too important not to leave to economists. More on how I learned that lesson next week..

. xxx

Meanwhile, the best article I read last week on Russia’s war in Ukraine is “How to Make Peace with Putin: The West must move quickly to end the war in Ukraine’’, by Thomas Graham and Rajan Menon. First time Foreign Affairs readers may see it for free, I believe.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Llewellyn King: We must face the fact that world crises in food, inflation and energy require tough decisions and new thinking

Messengers going to Job, each with bad news.

— 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a rough road ahead for the world and our political class isn’t leveling with us.

As Steve Odland, president and CEO of The Conference Board, one of the nation’s premier business-research organizations, said in a television interview, serious inflation will continue at least until 2024, and longer if things continue to deteriorate with supply-chain crises and the war in Ukraine.

Particularly, Odland, who also serves as a director of General Mills Inc., fears a global food crisis with famine in Africa and many other vulnerable places if Ukrainian farmers don’t start seeding spring crops to start this year’s harvest. Already, Ukraine – once known as one of the world’s breadbaskets -- has cut off exports to make sure that there is enough food for their own people, as war rages.

Odland sees U.S. inflation continuing at 7 to 8 percent for several years at best. But his primary worry is global food supplies, as countries face a crisis of new and frightening proportions.

His second worry is stagflation. If the rate of productivity falls below 3 percent, “then we will have stagflation,” Odland told me during a recording of White House Chronicle, on PBS, the weekly news and public affairs program I produce and host.

Odland faults the Federal Reserve for being timid in raising interest rates to counter inflation.

I fault the political class for not leveling with us – both parties. As we are in a state of perpetual election fervor, we are also in a state of perpetual happy talk. “Get the rascals out, and all will be well when my band of happy angels will fix things.” That is what the political class says, and it is a lie.

We are in for a long and difficult period which began with the pandemic that disrupted supply chains and set off inflation, and now the war in Ukraine has compounded that. Supply chains won’t magically return to where they were before COVID-19 struck, and more likely they will have further constrictions because of the war. New supply chains need to be forged and that will take time.

For example, nickel, which is used in the batteries that are reshaping the worlds of electricity and transportation and for stainless steel, will have to come from places other than Russia. At present, Russia supplies 20 percent of the world’s voracious appetite for high-purity nickel. Opening new mines and expanding old ones will take time.

The world’s largest challenge is going to be food: starvation in many poor countries and high prices at the supermarkets in the rich ones, including the United States. There are technological and alternative supply fixes for everything else, but they will take time. Food shortages will hit early and will continue while the world’s farms adjust. There will be suffering and death from famine.

The curtailing of Russian exports will affect the United States in multiple ways, some of which might eventually turn out to be beneficial as the creative muscle is flexed.

In the utility industry, someone who is thinking big and boldly is Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association in Denver.

Highley told Digital 360, the weekly webinar that emanates from Texas State University in San Marcos, the challenging problem of electricity storage could be solved not with lithium-ion batteries, but with iron-air batteries.

In its simplest form, an iron-air battery harnesses the process of rusting to store electricity. The process of rusting is used to produce power when it is exposed to oxygen captured on site. To charge the battery, an electric current reverses the process and returns the rust to iron.

Clearly, as Highley said, this won’t work for electric vehicles because of the weight of iron. But in utility operations, these batteries could offer the possibility of very long drawdown times --not just four hours, as with current lithium-ion batteries. And there is plenty of iron stateside.

Another Highley concept is that instead of dealing with all the complexities of transporting hydrogen, it should be stored as ammonia, which is more easily handled.

This isn’t magical thinking, but the kind of thinking which will lead us back to normal -- someday.

Politicians should stop the happy talk and tell us what we are facing.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C

David Warsh: Knowledge and skepticism about the causes of inflation

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In their introduction to the conference volume Knowledge and Skepticism, its editors wrote that there are two main questions worth asking in epistemology. What is knowledge? And, do we have any of it? Their formulation has often come to mind these days in connection with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it has also welled-up in my thinking in connection with a very different matter, the phenomenon of inflation.

Charles Goodhart is a central banker’s expert on central banking. Having completed his PhD at Harvard University, in 1963, he worked for seventeen years as an adviser to the Bank of England on domestic monetary policy, during the tumultuous but ultimately successful battles in Britain and the United States against global inflation, all the while pursuing a thorough examination of the rationale for bank regulation in the first place.

In The Evolution of Central Banking (1988), he traced the history of the most important and least understood regulatory institution of modern government, and for the next thirty years remained in the forefront of the discussion of supervision of the world banking system.

Then, in 2020, with Manoj Pradhan, the 84-year-old Goodhart published The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival, arguing that that, owing to declining fertility rates in China and the West, the coronavirus pandemic has marked a watershed between the deflationary forces of the last thirty or forty years and a coming twenty years or so of rising prices. A headline of a recent story on the front page of The Wall Street Journal conveyed the story:

Will Inflation Stay High for Decades? One Influential Economist Says Yes

Charles Goodhart sees an era of inexpensive labor giving way to years of worker shortages—and higher prices. Central bankers around the world are listening.

Goodhart predicts that inflation in advanced economies will settle at 3 percent to 4 percent around the end of 2022 and remain at that level for decades, wrote WSJ reporter Tom Fairless, as opposed to about 1.5 percent in the decade before the pandemic, with interest rates correspondingly higher. The Black Death, a 14th Century pandemic, had triggered a similar quarter-century of soaring wages and rising prices, he observed. You can read Fairless’s story yourself, thanks to this free link.

The question is, if Goodhart is right, what should central bankers do about it? Ever since he first presented his findings to a meeting of central bankers in 2016, monetary policy specialists representing various interests and points of view have been arguing about it. “Lower for Longer, ‘‘the latest report of the technical advisory committee of the European Systemic Risk Boars, takes Goodhart’s argument into account and differs sharply.

Among the experts exists a 400- year-old difference of opinion, known by different names at different times, of which Keynesian and Monetarist or Freshwater Saltwater are only the most recent. Some conclude that making appropriate policy is relatively easy: Simply require the central bank to control the supply of money. Others say central bankers’ job is difficult. John Greenwood and Steve H. Hanke, of Johns Hopkins University, put it this way in a recent Journal of Corporate Finance,

There have always been two types of explanations for inflation: ad hoc explanations and monetary explanations. Historically, the ad hoc explanations have been in terms of special factors present on particular occasions: commodity price increases due to bad harvests, supply disruptions due to restrictions on international trade, profiteers or monopolists holding back scarce goods, or trades unions pushing up wages leading to a wage-price spiral or cost-push pressures, and so on in great variety. Even the widely used aggregate demand-aggregate supply model is a species of ad hoc explanation in the sense that it relies on idiosyncratic factors driving estimates of the output gap or special factors affecting the supply of labor or productivity.

The monetary explanations for inflation have focused on increases in the quantity of money: either new discoveries of gold and silver in centuries past, or fiat money creation by the banking system or by the central bank in modern times.

I am an economic journalist, not an economist, and to my mind, there has always seemed something a circular about the shorthand explanation of rising prices, to the effect that “inflation is a matter of too much money chasing too few goods.” By making “rising prices” of goods synonymous with “inflation” of the quantity of money, the language of the shorthand assumes its own truth, and gives short shrift to the changing nature of “goods.” What about the declining fertility rate in China and the West?

As a journalist, I’ve come to think that a more revealing formulation of the difference of opinion about rising (or falling) prices is to be found in Joseph Schumpeter’s History of Economic Analysis (1954), where the economist distinguished between real and monetary analysis. Real analysis, Schumpeter wrote, is old as Aristotle. It “proceeds from the principle that all the essential phenomena of economic life are capable of being described in terms of goods and services, of decisions about them, and relations between them. Money enters the picture only in the modest role of a technical device that had been adopted in order to facilitate transactions,” and, occasionally, in the central role of what are described as “monetary disorders.”

Monetary analysis, Schumpeter continued, denies that money is of secondary importance in economic affairs., “We need only observe the course of events during and after the California gold discoveries to solidify ourselves that these discoveries were responsible for a great deal more than a change in the unit with which values are expressed,” he added, observing that money serves as a store of value as well as a means of transacting business.

Nor have we any difficulty in realizing – as A. Smith did – that the development of an efficient banking system may make a lot of difference in the development of a country’s wealth.

Schumpeter did not have an especially high opinion of Adam Smith!

As it happens, I wrote a book about all this forty years ago. As a magazine writer in New York, I had come across a 700-year index of the cost of living in a certain fashion in England. It showed two decades-long periods of steadily rising prices, one in the 16th Century, another in the 18th, both of which eventually leveled off, never returning to their prior levels. So I wrote in 1975 that the rising prices of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, too, would probably level off one day, though I didn’t venture why or when, much less mention Paul Volcker, the Federal Reserve Board chairman in 1979-1987.

My interest piqued, I spent a year in the New York Public Library unburdening myself of (some of) my ignorance, before turning back to the task of earning a living, this time as a newspaperman in Boston. By then I was more interested in the history of technology and government. Money and banking? Yawn! The Idea of Economic Complexity finally emerged in 1984, with nothing more to unify those ad hoc accounts of rising prices than the word complexity; intuitively appealing, perhaps, but analytically empty. It was a shaggy little book, in James Fallows’s apt description, politely received and quickly forgotten.

But before it was, Charles P. Kindleberger replied to a note I had written to say that I was entirely right that complexity does not communicate itself to economists, “at least not to this economist.” Kindleberger and I gradually became friends, and gradually I learned how little I understood how about the languages in which economist wrote for one another. Since then my knowledge of economics has increased to include, for example, the distinction between real and monetary analysis, and so has my admiration for what professional economist have achieved in the 250 years they have been doing business together. But then so have my doubts that economists have yet learned all there is to know about the understanding their science can produce. And, suddenly, primers on “inflation” are back in the news for the first time since in forty years.

So I plan to write a few pieces, half a dozen in all, one after another, about what I have learned about what I was trying to say forty years ago, anchoring each in a particular book or article that opened my eyes. I am not a true skeptic in the philosophers’ senses; don’t think that nobody knows anything: I think that economists know a lot. But I believe that they are still learning, that there are things that economists don’t yet know how to say, and that journalists can contribute to the conversation.

If you are looking for state-of-the-art knowledge, read Charles Goodhart. If you are interested in informed speculation, keep reading here. Better yet, do both. A lot of adventure lies ahead.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Lindsay Owens: Firms use ‘inflation’ as cover for price-gouging and record profits

1904 cartoon warning attendees of the St. Louis World's Fair of hotel room price-gouging.

Via OtherWords.org

If you’ve been slammed lately by higher prices on everything from groceries to rental cars and gas prices, you’re probably wondering what on earth is behind these skyrocketing costs.

Corporations are quick to blame this new reality on the pandemic, but another major culprit is hiding in plain sight: their own profiteering.

Four times a year, corporations are required by law to update their investors on how they’re doing in terms of sales and profits. These are called “earnings reports,” and the companies will usually hold calls with the investors to walk them through the latest report.

My organization, Groundwork Collaborative, recently got our hands on the transcripts from hundreds of these earnings calls. And you won’t believe what CEOs are boasting about.

Knowing that the current inflation frenzy is a convenient scapegoat, these companies are charging customers even more to pad their profit margins. They are just admitting it — they’re openly bragging to investors about how well it’s working.

“I think we’ve done a great job with our pricing,” boasted the CFO of Hormel, a maker of popular grocery brands. “I think it’s been very effective.” As prices went up, the company improved its operating income by 19 percent in the first quarter of 2022 compared to 2021.

Constellation Brands, the parent company of popular beers Modelo and Corona, is also engaging in bald-faced profiteering. On its January call, Constellation’s CFO admitted that its consumer base “skews a bit more Hispanic” and the company wants to “take as much as [we] can” from them.

And now, the conflict in Ukraine is providing yet another opportunity for oil and gas companies to pad their bottom lines. “It’s tragic what’s going on in Eastern Europe,” said one oil executive in late February. “But if anything, these high prices, the volatility, drive even more energy security and long-term contracting.”

This pandemic profiteering is taking a massive toll on consumers, workers and small businesses.

Low-income Americans are pinching pennies to feed their families and pay their bills. And while mega-companies can use their market power to raise prices and generate record profits, small businesses and independent retailers are struggling to keep their doors open.

The appalling price-gouging and monopolistic behavior we’re monitoring comes on top of decades of disinvestment in our workers and supply chain, excessive corporate power and financial markets maximizing short-term profits. This broken system left us wholly unprepared to accommodate increases in demand.

But make no mistake: next time you experience sticker shock in the checkout line, it’s a safe bet that corporate executives and shareholders are reaping the rewards.

People are catching on: A new poll from Data for Progress and Groundwork finds that 63 percent of voters believe that “large corporations are taking advantage of the pandemic to raise prices unfairly on consumers and increase profits.”

Policy makers are taking notice, too. The New York state attorney general’s office just announced new price-gouging rules, paving the way for other states to follow suit.

And days after President Biden promised action on pandemic price-gouging, congressional oversight panels opened investigations into the three major ocean shipping alliances. These outfits control about 80 percent of seaborne cargo and have seen their profits increase seven-fold from the previous year.

Finally, a recently introduced bill, the COVID-19 Price Gouging Prevention Act, would help the Federal Trade Commission and State Attorneys General protect people across the country from pandemic profiteering.

Without competition and robust regulation to keep them in check, big corporations have gotten away with using the pandemic to push up prices and fatten their profit margins — and if they aren’t reined in, high prices could be here to stay.

Lindsay Owens is the executive director of Groundwork Collaborative.