Victoria Knight: No, your cotton face mask isn’t all that effective

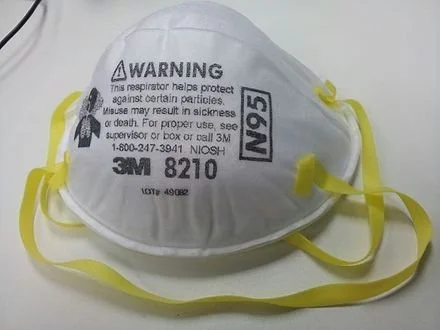

This N95 mask is highly effective.

— Photo by Banej

From Kaiser Health News in cooperation with PolitiFact

“From the perspective of knowing how covid is transmitted, and what we know about omicron, wearing a higher-quality mask is really critical to stopping the spread of omicron.’’

— Dr. Megan Ranney, academic dean for the School of Public Health at Brown University.

The highly transmissible omicron variant is sweeping the U.S., causing a huge spike in COVID-19 cases and overwhelming many hospital systems. Besides urging Americans to get vaccinated and boosted, public health officials are recommending that people upgrade from their cloth masks to higher-quality medical-grade masks.

But what does this even mean?

At a recent Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing, top public health officials displayed different types of masking. Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, wore what appeared to be a surgical mask layered under a cloth mask, while Dr. Anthony Fauci, chief medical adviser to the president, wore what looked like a KN95 respirator.

(Dr. Wakensky was formerly chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.)

Some local governments and other organizations are offering their own policies. Los Angeles County, for instance, will require as of Jan. 17 that employers provide N95 or KN95 masks to employees. In late December, the Mayo Clinic began requiring all visitors and patients to wear surgical masks instead of cloth versions. The University of Arizona has banned cloth masks and asked everyone on campus to wear higher-quality masks.

Questions about the level of protection against COVID that masks provide — whether cloth, surgical or higher-end medical grade — have been a subject of debate and discussion since the earliest days of the pandemic. We looked into the question last summer. And as science changes and variants emerge with higher transmissibility, so do opinions.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has not updated its mask guidance since October, before the omicron variant emerged. That guidance doesn’t recommend the use of an N95 respirator but states only that masks should be at least two layers, well-fitting and contain a nose wire.

Multiple experts we consulted said that the current CDC guidance does not go far enough. They also agreed on another point: Wearing a cloth mask is better than not wearing a mask at all, but if you can upgrade — or layer cloth with surgical — now is the time.

Although cloth masks may appear to be more substantial than the paper surgical mask option, surgical masks as well as KN95 and N95 masks are infused with an electrostatic charge that helps filter out particles.

“From the perspective of knowing how COVID is transmitted, and what we know about omicron, wearing a higher-quality mask is really critical to stopping the spread of omicron,” said Dr. Megan Ranney, academic dean for the School of Public Health at Brown University.

A large-scale real-world study conducted in Bangladesh and published in December showed that surgical masks are more effective at preventing covid transmission than cloth masks.

So, one easy strategy to improve protection is to layer a surgical mask underneath cloth. Surgical masks can be bought relatively cheaply online and reused for about a week.

Ranney said she advises people who opt for layering to put the better-quality mask, such as the surgical mask, closest to your face, and put the lesser-quality mask on the outside.

If you’re really pressed for resources, Dr. Stephen Luby, a professor specializing in infectious diseases at Stanford University and one of the authors of the Bangladesh mask study, said surgical masks can be washed and reused, if finances are an issue. Nearly two years into the pandemic, such masks are cheap and plentiful in the U.S. and many retailers make them available free of charge to customers as they enter businesses.

“During the study, we told the participants they could wash the surgical masks with laundry detergent and water and reuse them,” Luby said. “You lose some effect of the electrostatic charge, but they still outperformed cloth masks.”

Still, experts maintain that wearing either a KN95 or an N95 respirator is the best protection against omicron, since these masks are highly effective at filtering out viral particles. The “95” in the names refers to the masks’ 95% filtration efficacy against certain-sized particles. N95 masks are regulated by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, while KN95s are regulated by the Chinese government and KF94s by the South Korean government.

Americans were initially urged not to buy either surgical or N95 masks early in the pandemic to ensure there would be a sufficient supply for health care workers. But now there are enough to go around.

So, if you have the resources to upgrade to an N95, a KN95 or a KF94 mask, you should absolutely do so, said Dr. Leana Wen, a professor of health policy and management at George Washington University. Although these models are more expensive and can be more uncomfortable, they are worth the investment for the safety they provide, she said.

“[Omicron is] a much more contagious virus, so there is a much lower margin of error in regards to the activities you were once able to do without getting infected,” Wen said. “We have to increase our protection in every way, because everything is riskier now.”

Wen also said that though these masks are characterized as one-use, unless you are in a health care setting, KN95s and N95s can be worn more than once. She uses one of her personal KN95s for more than a week at a time.

Another important thing to note is there are many counterfeit N95 and KN95 masks being sold online, so consumers must be careful when ordering them and be sure to get them only from a legitimate, trusted vendor.

The CDC maintains a list of NIOSH-approved N95 respirators. Wirecutter and The Strategist have both published guides to purchasing approved KN95 and KF94 masks. Ranney also recommends consulting the website Project N95 or engineer Aaron Collins’s “Mask Nerd” YouTube channel.

And remember, the risk of transmission depends not just on the mask you wear but also the masking practices of others in the room — so going into a meeting or restaurant where others are unmasked or wearing only cloth masks increases the odds of getting infected, no matter how careful you are. This chart demonstrates the huge differences.

Even with a mask upgrade, if you are still worried about omicron and, in particular, a serious case of , the No. 1 thing you can do to protect yourself is get vaccinated and boosted, said Dr. Neal Chaisson, an assistant professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“There’s been a lot of talk about people who have been vaccinated getting omicron,” said Chaisson. “But I’ve been working in the ICU and probably 95% of the patients that we’re taking care of right now did not take the advice to get vaccinated.”

Victoria Knight is a Kaiser Health News reporter

vknight@kff.org, @victoriaregisk

Linda Gasparello: What’s good for us can be very bad for wildlife

Remains of an albatross killed by ingesting plastic pollution.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

When I lived in Manhattan, I pursued an unusual pastime. I started it to avoid eye contact with Unification Church members who peddled flowers and their faith on many street corners in the 1970s. If a Moonie (as a church member was derisively known) were to approach me, I’d cast my eyes down to the sidewalk, where I’d see things that would set my mind wandering.

In the winter, I’d see lone gloves and mittens. On the curb in front of La Cote Basque on East 55th Street, the luxe French restaurant where Truman Capote dined with the doyennes of New York’s social scene, before dishing on them in his unfinished novel, Answered Prayers, I saw a black leather glove with a gold metal “F” sewn on the cuff. I coveted such a Fendi pair, eyeing them at the glove counter at Bergdorf Goodman, but not buying them – they cost about a third of my Greenwich Village studio apartment’s monthly rent in the late 1970s. On the sidewalk on Fifth Avenue, in front of an FAO Schwartz window, I saw a child’s mitten, expertly knit in a red-and-white Norwegian pattern that I never had the patience to follow. I wondered whether the child dropped the mitten after removing it to point excitedly to a toy in the window.

In the summer, I’d see pairs of sunglasses and single sneakers on the sidewalks, things that had fallen out of weekenders’ pockets and bags. It wasn’t unusual for me to see pantyhose. Working women in Manhattan, in my time there, could wear a short-sleeved wrap dress – the one designed by Diane von Furstenberg was the working woman’s boilersuit -- in the summer, but they’d better have put on pantyhose, or packed a pair in their pocketbooks or tote bags. The pantyhose would fall out of them and roll like tumbleweed along the avenues.

One summer morning on Perry Street, near where I lived, I saw a long, black zipper. It looked like a black snake had slithered out of a drain grate on the street and was warming itself on the asphalt, its white belly gleaming in the sun.

Now when I walk on a city sidewalk, I still look down, not to pursue my pastime but to preserve myself from tripping and falling on stuff. I sometimes see interesting litter, but mostly I see single-use and reusable face masks.

This fall, as I walked on the waterfront promenade along Rondout Creek in Kingston, N.Y., I saw a single-use mask swirling in the wind with the fallen leaves. I grabbed the mask and deposited it in a trash can, worried that it would fall into the creek, ensnarling the waterfowl and the fish.

In the COVID-19 crisis, masks have been lifesavers. But masks, especially single-use, polypropylene surgical masks, have been killing marine wildlife and devastating ecosystems.

Billions of masks have been entering our oceans and washing onto our beaches when they are tossed aside, where waste-management systems are inadequate or nonexistent, or when these systems become overwhelmed because of increased volumes of waste.

A new report from OceansAsia, a Hong Kong-based marine conservation organization, estimates that 1.56 billion masks will have entered the oceans in 2020. This will result in an additional 4,680 to 6,240 metric tons of marine plastic pollution, says the report, entitled “Masks on the Beach: The impact of COVID-19 on Marine Plastic Pollution.”

Single-use masks are made from a variety of meltdown plastics and are difficult to recycle, due to both composition and risk of contamination and infection, the report points out. These masks will take as long as 450 years to break down, slowly turning into microplastics ingested by wildlife.

“Marine plastic pollution is devastating our oceans. Plastic pollution kills an estimated 100,000 marine mammals and turtles, over a million seabirds, and even greater numbers of fish, invertebrates and other animals each year. It also negatively impacts fisheries and the tourism industry and costs the global economy an estimated $13 billion per year,” according to Gary Stokes, operations director of OceansAsia.

The report recommends that people wear reusable masks, and to dispose of all masks properly.

I hope that everyone will wear them for the sake of their own and others’ health, and that I won’t see them lying on sidewalks on my strolls, or on beaches, where they are a sorry sight.

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. Her email is whchronicle@gmail.com and she’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Victoria Knight: Inadequate data on efficacy of face masks

“We simply don’t have data to say this,” Andrew Lover, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

A popular social media post that’s been circulating on Instagram and Facebook since April depicts the degree to which mask-wearing interferes with the transmission of the novel coronavirus. It gives its highest “contagion probability” — a very precise 70% — to a person who has COVID-19 but interacts with others without wearing a mask. The lowest probability, 1.5%, is when masks are worn by all.

The exact percentages assigned to each scenario had no attribution or mention of a source. So we wanted to know if there is any science backing up the message and the numbers — especially as mayors, governors and members of Congress increasingly point to mask-wearing as a means to address the surges in coronavirus cases across the country.

Doubts About The Percentages

As with so many things on social media, it’s not clear who made this graphic or where they got their information. Since we couldn’t start with the source, we reached out to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to ask if the agency could point to research that would support the graphic’s “contagion probability” percentages.

“We have not seen or compiled data that looks at probabilities like the ones represented in the visual you sent,” Jason McDonald, a member of CDC’s media team, wrote in an email. “Data are limited on the effectiveness of cloth face coverings in this respect and come primarily from laboratory studies.”

McDonald added that studies are needed to measure how much face coverings reduce transmission of COVID-19, especially from those who have the disease but are asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic.

Other public health experts we consulted agreed: They were not aware of any science that confirmed the numbers in the image.

“The data presented is bonkers and does not reflect actual human transmissions that occurred in real life with real people,” Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine at the University of California-San Francisco, wrote in an email. It also does not reflect anything simulated in a lab, he added.

Andrew Lover, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, agreed. He had seen a similar graphic on Facebook before we interviewed him and done some fact-checking on his own.

“We simply don’t have data to say this,” he wrote in an email. “It would require transmission models in animals or very detailed movement tracking with documented mask use (in large populations).”

Because COVID-19 is a relatively new disease, there have been only limited observational studies on mask use, said Lover. The studies were conducted in China and Taiwan, he added, and mostly looked at self-reported mask use.

Research regarding other viral diseases, though, indicates masks are effective at reducing the number of viral particles a sick person releases. Inhaling viral particles is often how respiratory diseases are spread.

SOURCES:

ACS Nano, “Aerosol Filtration Efficiency of Common Fabrics Used in Respiratory Cloth Masks,” May 26, 2020

Associated Press, “Graphic Touts Unconfirmed Details About Masks and Coronavirus,” April 28, 2020

BMJ Global Health, “Reduction of Secondary Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Households by Face Mask Use, Disinfection and Social Distancing: A Cohort Study in Beijing, China,” May 2020

Email interview with Andrew Noymer, associate professor of population health and disease prevention, University of California-Irvine, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Jeffrey Shaman, professor of environmental health sciences and infectious diseases, Columbia University, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Linsey Marr, Charles P. Lunsford professor of civil and environmental engineering, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Peter Chin-Hong, professor of medicine, and George Rutherford, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California-San Francisco, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Werner Bischoff, medical director of infection prevention and health system epidemiology, Wake Forest Baptist Health, June 30, 2020

Email statement from Jason McDonald, member of the media team, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 29, 2020

The Lancet, “Physical Distancing, Face Masks, and Eye Protection to Prevent Person-to-Person Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” June 1, 2020

Nature Medicine, “Respiratory Virus Shedding in Exhaled Breath and Efficacy of Face Masks,” April 3, 2020

Phone and email interview with Andrew Lover, assistant professor of epidemiology, University of Massachusetts Amherst, June 29, 2020

Reuters, “Partly False Claim: Wear a Face Mask; COVID-19 Risk Reduced by Up to 98.5%,” April 23, 2020

The Washington Post, “Spate of New Research Supports Wearing Masks to Control Coronavirus Spread,” June 13, 2020

One recent study found that people who had different coronaviruses (not COVID-19) and wore a surgical mask breathed fewer viral particles into their environment, meaning there was less risk of transmitting the disease. And a recent meta-analysis study funded by the World Health Organization found that, for the general public, the risk of infection is reduced if face masks are worn, even if the masks are disposable surgical masks or cotton masks.

The Sentiment Is On Target

Though the experts said it’s clear the percentages presented in this social media image don’t hold up to scrutiny, they agreed that the general idea is right.

“We get the most protection if both parties wear masks,” Linsey Marr, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech who studies viral air droplet transmission, wrote in an email. She was speaking about transmission of COVID-19 as well as other respiratory illnesses.

Chin-Hong went even further. “Bottom line,” he wrote in his email, “everyone should wear a mask and stop debating who might have [the virus] and who doesn’t.”

Marr also explained that cloth masks are better at outward protection — blocking droplets released by the wearer — than inward protection — blocking the wearer from breathing in others’ exhaled droplets.

“The main reason that the masks do better in the outward direction is that the droplets/aerosols released from the wearer’s nose and mouth haven’t had a chance to undergo evaporation and shrinkage before they hit the mask,” wrote Marr. “It’s easier for the fabric to block the droplets/aerosols when they’re larger rather than after they have had a chance to shrink while they’re traveling through the air.”

So, the image is also right when it implies there is less risk of transmission of the disease if a COVID-positive person wears a mask.

“In terms of public health messaging, it’s giving the right message. It just might be overly exact in terms of the relative risk,” said Lover. “As a rule of thumb, the more people wearing masks, the better it is for population health.”

Public health experts urge widespread use of masks because those with COVID-19 can often be asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic — meaning they may be unaware they have the disease, but could still spread it. Wearing a mask could interfere with that spread.

Our Ruling

A viral social media image claims to show “contagion probabilities” in different scenarios depending on whether masks are worn.

Experts agreed the image does convey an idea that is right: Wearing a mask is likely to interfere with the spread of COVID-19.

But, although this message has a hint of accuracy, the image leaves out important details and context, namely the source for the contagion probabilities it seeks to illustrate. Experts said evidence for the specific probabilities doesn’t exist.

We rate it Mostly False.

Victoria Knight is a journalist at Kaiser Health News.