David Warsh: Of economics ideas and the power of big business to shape policies

Theater lobby card for the American short comedy film Big Business (1924)

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, by Nami Oreskes and Erik Conway, was a hard-hitting history in 2010 that catapulted its authors to fame – Oreskes all the way to Harvard University; Conway remained at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech.

Their new book – The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market (Bloomsbury, 2023) – the authors describe as a prequel. In identifying the doubters, it exhibits the same strengths as before. It displays greater weaknesses in establishing the various truths of the matter. It is, however, a page-turner, a powerful narrative, especially if you are already feeling a little paranoid and looking for a good long summer read.

It’s all true, at least as far as it goes. Those three powerful intellects – Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises – started with unpopular arguments and won big. From the National Electric Light Association and the Liberty League in the Twenties and Thirties, the National Association of Manufacturers and the US Chamber of Commerce in the Fifties and Sixties, to the Federalist Society and the Club for Growth of today, business interests have been spending money and working behind the scenes to boost enthusiasm for markets and to undermine faith in government initiative.

To tell their gripping story of ideas and money, Oreskes and Conway rely on much work done before. Pioneers in this literature include Johan Van Overveldt (The Chicago School: How the University of Chicago Assembled the Thinkers who Revolutionized Economics and Business, 2007); Steven Teles (The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The Battle for Control of the Law); 2008); Kim Phillips-Fein, (Invisible Hands: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, 2009); Jennifer Burns (Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, 2009); Phillip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe (The Road to Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, 2009); Daniel Rodgers (Age of Fracture, 2011); Nicholas Wapshott (Keynes Hayek: The Clash that Defined Modern Economics, 2011); Angus Burgin (The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression, 2012); Daniel Stedman Jones (Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, 2012); Robert Van Horn, Phillip Mirowski and Thomas Stapleford, (Building Chicago Economics: New Perspectives on the History of America’s Most Powerful Economics Program, 2011); Avner Offer, and Gabriel Söderberg (The Nobel Factor: The Prize in Economics, Social Democracy, and the Market Turn, 2016); Lawrence Glickman (Free Enterprise: An American History, 2019); Binyamin Appelbaum (The Economists’ Hour: False Prophets, Free Markets, and the Fracture of Society) 2019); Jennifer Delton (The Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American Capitalism, 2020); and Kurt Andersen (Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America a Recent History, 2020). Biographies of Robert Bartley and Roger Ailes remain to be written.

So about those weaknesses? They boil down to this: In The Big Myth you seldom get the other side of the story. Take a fundamental example. Oreskes and Conway assert that “the claim that America was founded on three basic interdependent principles: representative democracy, political freedom, and free enterprise,” cooked up in the Thirties by the National Association of Manufactures for an advertising campaign. This so-called called “Tripod of Freedom” was “fabricated,” Oreskes and Conway maintain; the words free enterprise appear nowhere in the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution, they declare. That stipulation amounts to a curious “blind spot,” Harvard historian Luke Menand observed in a lengthy review in The New Yorker. There are mentions of property, though, writes Menand, “and almost every challenge to government interference in the economy rests on the concept of property.” See Adam Smith’s America: How a Scottish Philosopher Became an Icon of American Capitalism (Princeton, 2022), by Glory Liu, for elaboration.

Similarly, the previous Big Myth with which the market fundamentalists and the business allies were contending received little attention. As the industrial revolution gathered pace in the late 19th Century, progressives in the United States preached a gospel of government regulation. Germany’s success in nearly winning World War I received widespread attention. Britain emerged from World War II with a much more socialized economy than before. And in the U.S., government planning was espoused by such intellectuals as James Burnham and Karl Mannheim as the wave of the future.

Finally, The Big Myth largely ignores the experiences of ordinary Americans in the years that it covers. For all the fury that Big Coal mounted against the Tennessee Valley Authority, its dams were built, nevertheless. There is only a single fleeting mention of George Orwell, though his novels Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949) probably influenced far more people than Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. Paul Samuelson’s textbook explanation of the workings of “the modern mixed economy” dominated Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom tract for forty years and probably still does.

Yet there can be no doubt that there was a disjunction. Oreskes and Conway mention that in the ‘70’s conservative historian George Nash considered that nothing that could be described as a conservative movement in the mid-’40s, that libertarians were a “forlorn minority.” President Harry Truman was reelected in 1948, and Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate Republican, served for eight years after him. Suddenly. in 1964, Republicans nominated libertarian Barry Goldwater. Then came Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

What happened? America’s Vietnam War, for one thing. Globalization for another. Massive migrations occurred in the US, Blacks and Hispanics to the North, businesses to the West and the low-cost South. Civil rights of all sorts revolutions unfolded, at all points of the compass. The composition of Congress and the Supreme Court changed all the while.

In Merchants of Doubt, Oreskes and Conway were on sound ground when making claims about tobacco, acid rain, DDT, the hole in the atmosphere’s ozone layer and greenhouse-gas emissions. These were matters of science, an enterprise devoted to the pursuit of questions in which universal agreement among experts can reasonably hope to be obtained. It was sensible to challenge the reasoning of skeptics in these matters, and to probe the outsized backing they received from those with vested interests. The interpretation of a hundred years of American politics is not science; much of it is not even a topic for proper historians yet. Agreement is reached, if at all, through elections, and elections take time.

Again, take a small matter, the interpretation of “the Reagan Revolution.” Jimmy Carter started it, Oreskes and Conway maintain; Bill Clinton finished it via the “marketization” of the Internet, and most persons have suffered as a result. It is equally common to hear it proclaimed that Reagan presided over an agreement to repair the Social Security system for the next fifty years, ended the Cold War on peaceful terms, and, by accelerating industrial deregulation, ensured on American dominance in a new era of globalization.

In arguments of this sort, EP prefers Spencer Weart’s The Discovery of Global Warming to Merchants of Doubt and Jacob Weisberg In Defense of Government: The Fall and Rise of Public Trust to The Big Myth. But I share Oreskes’ s and Conway’s concerns while searching for opportunities to build more consensus. A century after today’s market fundamentalists began their long argument with Progressive Era enthusiasts for government planning, sunlight remains the best disinfectant.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Deconstructing Hayek; does market get technology’s direction right?

John Singer Sargent's iconic World War I painting “Gassed”, showing blind casualties on a battlefield after a mustard gas attack. The same chemists’ work had resulted in creating highly useful fertilizers — and poison gas and very powerful explosives.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I was looking forward to the session on Hayek at the economic meetings in New Orleans last week. As a soldier of the revolution, I had learned a good deal from Hayek back in the day, when his occasional pieces sometimes appeared in Encounter magazine. (I knew Hayek had been the prime mover behind the founding of the classically liberal pro-markets Mont Pelerin Society in 1947; knew, too, that Encounter has been partly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency, in 1953, in an effort to counter Cold War ambivalence.

I understood that Hayek was one of a handful of economists who had been especially influential before John Maynard Keynes swept the table in the Thirties. Others included Irving Fisher, Joseph Schumpeter, A.C. Pigou, Edward Chamberlin, and Wesley Clair Mitchell. What revolution? We journalists were hoping to glimpse economics whole. The economists whom we read (and other social scientists, historians, and philosophers) seemed as blind men handling an elephant. Each described some part of the truth.

The session devoted to Bruce Caldwell’s new biography, Hayek: A Life: 1899-1950 (Chicago, 2022), didn’t disappoint. Presiding was Sandra Peart, of the University of Richmond, an expert on the still-born Virginia school of political economy of the Fifties (as opposed to the Chicago school of economics), with which Hayek was sometimes connected. Cass Sunstein, of the Harvard Law School; Hansjörg Klausinger, of Vienna University of Economics and Business; and Vernon Smith, of Chapman University, zoomed in. Steven N. Durlauf, of the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy (and editor if the Journal of Economic Literature); Emily Skarbek, of Brown University, were present discussants; as was, of course, Caldwell himself. The reader-friendly Hayek: A Life was itself the star of the show: a gracefully documented and thoroughly knowledgeable story of Vienna, New York, Berlin, London and Chicago, during those luminous years. I look forward to the second volume, 1950-1992.

Then I walked half a mile down New Orleans’ Canal Street to hear the American Economic Association Distinguished Lecture by Daron Acemoglu, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This was a very different world from that of Hayek.

For one thing, “Distorted Innovation: Does the Market Get the Direction of Technology Right?” wasn’t really a lecture at all. It was a technical paper, presenting a simple mode of directed technology, with which Acemoglu has been working for twenty-five years, followed by discussions of several examples of what Acemoglu described as instances in which technologies have become distorted by shifting incentives: energy, health and medical markets; agriculture; and modern automation technologies. The paper begins in jaunty fashion,

There is broad agreement that technical change has been a major engine of economic growth and prosperity during the last 250 years, However not all innovations are created equal and the direction of technology matters greatly as well.

What constitutes the “direction of technical change?” Acemoglu offered a striking example. Early 20th-century chemists in Germany, led by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, developed an industrial process for converting atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. Synthetic fertilizers thereby rendered commercial, greatly improved agricultural yields around the world. But the same processes were employed in industrial production of potent explosives and poisonous gases which killed millions of soldiers and civilians during World War I. Which direction might an effective social planner have preferred?

One view, the one for which Hayek is famous, is that the market is the best judge of which technologies to develop. There may be insufficient incentives to innovate initially, but once the government provides the requisite research infrastructure and support, it should stand aside. What the market thinks right, meaning profitable, is right, in this view.

Diametrically opposite, Acemoglu said, is the view that the politicians, planners and bureaucrats can decide on these matters as well as or even better than markets, and therefore they should set both the overall level of innovation and seek to influence its direction. This is welfare economics, a style of economic analysis pioneered after 1911 by A.C. Pigou, then the professor of economics at Cambridge University, and, for twenty-five years, perhaps the most influential economist in the world.

In his paper Acemoglu sought to describe an intermediate position, in which markets exist to experiment in order to determine which innovations are feasible, whereupon planners have a role in applying economic analysis to gauge otherwise unexamined side-effects of various sorts that may arise from a pursuing a particular path.

It was an unusual lecture, pitched to the level of a graduate seminar, and even before Acemoglu finished, individuals began drifting off to dinner engagements. The good news is that there is a book on its way. Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (Public Affairs),by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson will appear in May. Still better news is that it tackles head-on questions about automation, artificial intelligence, and income distribution that currently abound.

With three big books behind him — Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy; Why Nations Fail; and The Narrow Corridor, all with James Robinson, of the University of Chicago Harris School – behind him, Acemoglu is among the leading intellectuals of the present day. As heir to the leadership roles played by Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow, and Peter Diamond, he packs intuitional punch as well. Pay attention! Get ready for a battle royale.

The tectonic plates of scientific economics are shifting — large-scale processes are affecting the structure of the discipline. That revolution I mentioned at the beginning? The one in whose coverage we economic journalists are engaged? Its fundamental premise is that, while politics always plays a part in the background, economics makes progress over the years. In other words, Hayek takes a back seat to Acemoglu.

David Warsh: Cambridge will be even more of a capital of economics than usual this month

MIT’s main campus, in Cambridge

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

For the first time in three years the Summer Institute of the National Bureau of Economic Research is meeting in-person in Cambridge, Mass., at least for the most part, with some on-line components as well. (In the days before Zoom, venture capitalists used to describe more expensive face-to-face gatherings as “flesh-meets,” to distinguish them from conference calls.) A parallel, pan-European policy research institution, the Centre for Economic Policy Research, now headquartered in Paris, was founded in 1983.

A substantial fraction of the NBER’s 1,700+ research affiliates, who are drawn from colleges and universities mostly in North America, and a few others scattered around the world, will troop through the Sonesta Hotel in East Cambridge over the next three weeks, along with enough colleagues and students to add up to an attendance of some 2,400 persons in all. It is the forty-fifth annual meeting of what has become, in essence, a highly decentralized Wimbledon-style tournament of applied economists, staged as a science fair, and conducted in a series of high-level seminars.

Wimbledon, in that NBER players are professionally ranked; affiliates are selected by peer-review. Decentralized, in that 49 different projects are on the docket, many of them overlapping. Science fair, in that investigators choose their own problems, and rely on agreed-upon methods to study them, while new methods themselves are the subject of a separate annual lecture. Seminars, in that presenters don’t simply read their papers they have written; they briefly describe them and then respond to discussants and badinage.

An overall program is here. A detailed day-by-day listing of sessions is here. First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund Gita Gopinath, of Harvard University, is slated to deliver the Martin Feldstein Lecture July 19 at 5:15p.m. EDT. It’s titled “Managing a Turn in the Global Financial Cycle’’.

Meanwhile, a mile down the Charles River, the Russell Sage Foundation Summer Camp in Behavioral Economies has been underway in the Marriott Hotel, some twenty-five or thirty Ph.D. candidates and post-docs studying with leading researchers, under the direction of David Laibson and Matthew Rabin, both of Harvard University.

The Summer Institute is where economic policy approaches are argued among experts. Nobel Prizes emerge mostly from summer camps. I look forward to a lot of (virtual) running-around.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicsprincipals.com. where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Searching under streetlights for economic answers

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As a young magazine writer, I was a quick enough study to recognize that, in the discussion of inflation, the bourgeoning enthusiasm for monetary analysis had loaded the dice in favor of the quantity theory of money. New World treasure, paper money, central banking: it was as if monetary policy was a force independent of whatever might be happening in the economy itself. It reminded me a famous New Yorker cartoon, a patient talking to his psychoanalyst: “Gold was at $34 when my father died… it was $44 when I married my wife… now it’s $28, but I have trouble seeing.”

I wanted to suggest a variable that might represent the perspective of real analysis, though I did not yet know the term: the conviction, as I learned Joseph Schumpeter had described it, that “all the essential phenomena of economic life are capable of being described in terms of goods and services, of decisions about them, and relations between them,” and that money entered the picture as just another a technological device. Thinking about all else besides monetary innovation that was new in the world since the 15th Century, I came up with a catch-word to describe what had changed. The Idea of Economic Complexity (Viking) appeared in 1984.

It certainly wasn’t theory: more in the nature of criticism, a slogan with so little connection to the discourse of economics since Adam Smith that it didn’t bother specifying complexity of what. But the word had an undeniable appeal. “Complexity,” I wrote, “is an idea on the tip of the modern tongue.”

Sure enough: Chaos: Making a New Science, by James Gleick, appeared in 1987; Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Chaos and Order, by M. Mitchel Waldrop; and Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos, by Roger Lewin, followed in 1992; and in the next decade, a whole shelf of books appeared, of which The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Remaking of Economics, by Eric Beinhocker, in 2006, was probably the most interesting.

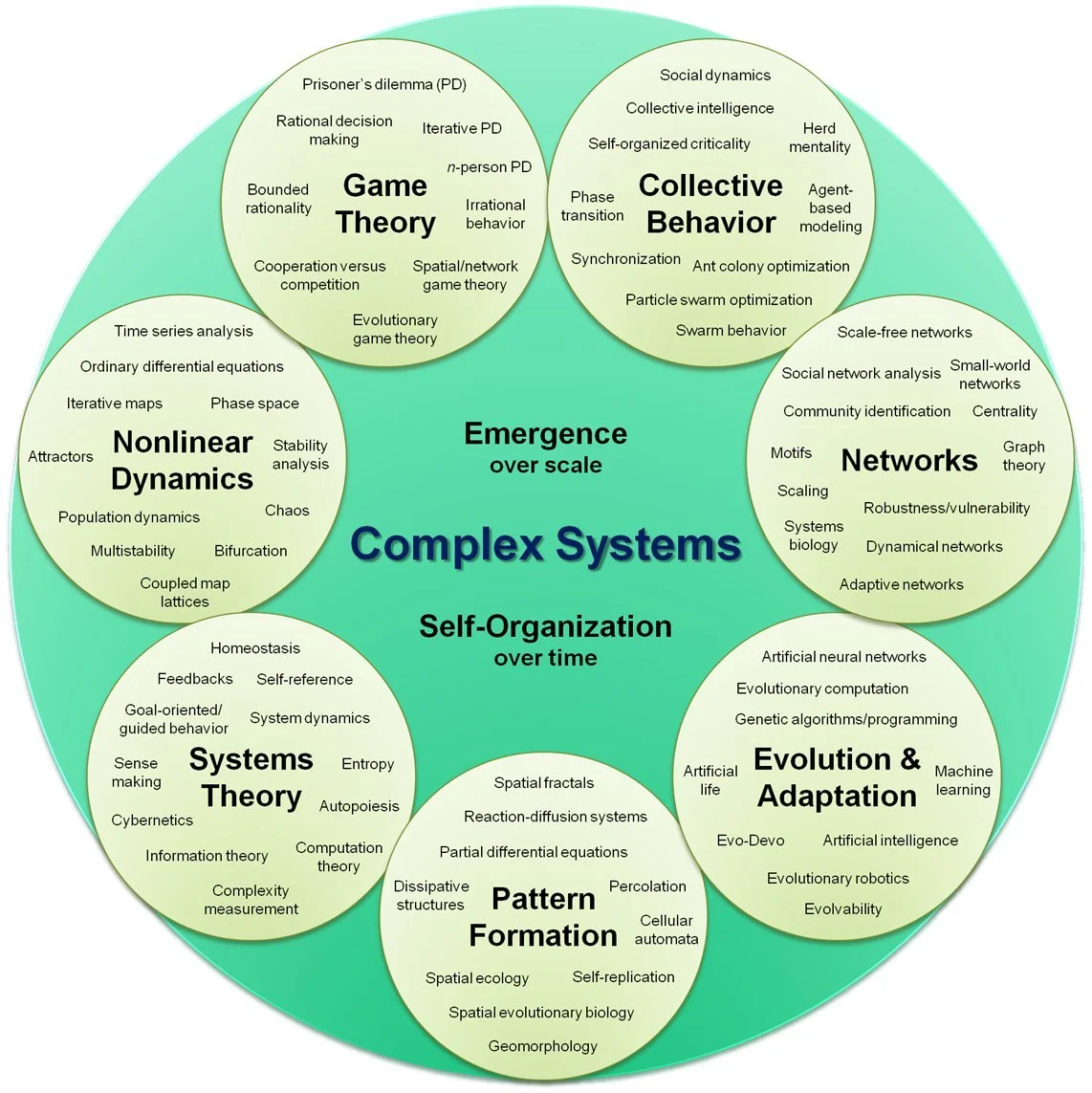

Organizational map of complex systems broken into seven sub-groups.

— Hiroki Sayama, D.Sc

But the question remained: complexity of what? The long quote-box on the back of the book jacket had put it this way:

To be complex is to consist of two or more separable, analyzable parts, so the degree of complexity of an economy consists of the number of different kinds of jobs in the system and the manner of their organization and interdependence in firms, industries, and so forth. Economic complexity is reflected, crudely, in the Yellow Pages, by occupation dictionaries, and by standard industrial classification (SIC) codes. It can be measured by sophisticate modern techniques, such a graph theory or automata theory. The whys and wherefores of our subject are not our subject here, however. It is with the idea itself that we are concerned. A high degree of complexity is what hits you in the face in a walk across New York City; it is what is missing in Dubuque, Iowa. A higher degree of specialization and interdependence – not merely more money or greater wealth – is what make the world of 1984 so different from the world of 1939.

Fair enough, for purposes of journalism. There was however something missing in my discussion: to wit, any real knowledge of structure of technical economic thought. I had come across the economist Allyn Young (1876-1929) in my reading, a little-remembered contemporary of Irving Fisher, Wesley Clair Mitchel and Thorstein Veblen, Schumpeter, and John Maynard Keynes. I classified him, with Schumpeter, as a “supply-sider,” in keeping with the controversies of the early ‘80’s, “locating in the businessman’s entrepreneurial search for markets the most profound impulse toward economic growth.” I added only that “We are coming at it from a slightly different direction is this book.”

It wasn’t until I re-read “Increasing Returns and Economic Progress” (for those who have access to JSTOR), in the Economic Journal of December 1928, that it dawned on me that it was complexity of the division of labor that I had been thinking about. A particular passage towards the end of Young’s paper brought it home.

The successors of the early printers, it has often been observed, are not only the printers of today, with their own specialized establishments, but also the producers of wood pulp, of various kinds of paper, of inks and their different ingredients, of type-metal and of type, the group of industries concerned with the technical parts of the producing of illustrations, and the manufacturers of specialized tools and machines for use in printing and in these various auxiliary industries. The list could be extended, both by enumerating other industries which are directly ancillary to the present printing trades and by going back to industries which, while supplying the industries which supply the printing trades, also supply other industries, concerned with preliminary stages in the making of final products other than printed books and newspapers. I do not think that the printing trades are an exceptional instance, but I shall not give other examples, for I do not want this paper to be too much like a primer of descriptive economics or an index to the reports of a census of production. It is sufficiently obvious, anyhow, that over a large part of the field of industry an increasingly intricate nexus of specialized undertakings has inserted itself between the producer of raw materials and the consumer of the final product.

Young, a University of Wisconsin PhD, had taught both Edward Chamberlin and Frank Knight as a Harvard professor, before accepting an offer from the London School of Economics to chair its department, at a time when LSE was looking to further distinguish itself. It was as president of Section F of the British Association for the Advancement of Science that he delivered his paper on increasing returns. Then, on the verge of returning to Harvard, he died at in an influenza epidemic. He was 52.

By the time that I re-read Young’s paper, I had met Paul Romer, a young mathematical economist then at the University of California Berkley, who had been working for years on more or less exactly the same questions that Allyn Young had raised in literary fashion fifty years before. Romer introduced me to the distinction economists made between “endogenous” and “exogenous” factors.

Endogenous were developments within the economic system; exogenous were those apparently outside, to be “bracketed” or put aside as matters the existing system hadn’t yet found ways to satisfactorily explain. Only a few years earlier, Robert Solow, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had been recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for, among other things, his finding that as much of 80 percent of economic growth in a certain period couldn’t be explained by additional increments of labor and capital. Whatever it was, it was to be expressed as a “Residual,” exogenous to the system of supply and demand.

First in “Growth Based on Increasing Return Due to Specialization,” in 1987, then in “Endogenous Technical Change,” in 1990, Romer solved the problem, employing new mathematics he had acquired to describe it. The magic of the Residual, it turned out, was human knowledge, a non-rival good in that, unlike land, labor, or capital, it could be possessed by any number of persons at the same time. I wrote a book about what had happened; Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton) appeared in 2006. In 2018, Romer, by then at New York University, and William Nordhaus, of Yale University, shared a Nobel Memorial Prize for their work on the interplay of technological development and climate change.

I had been hit by the meatball. I understood why Early Hamilton and John Neff had so little to say to each other, why Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson didn’t agree: they were men searching under streetlights for answers – different streetlights, separated by areas of darkness that had yet to be illuminated. I understood that economists could be trusted to continue to develop their field,

But there were still plenty of questions to be answered, including the one that had bothered me since the beginning. Why do we call rising prices “inflation?”

xxx

One of the joys of writing about the news is that you ordinarily never know where you’re going from one week to the next – reading as well, I expect. Yet from small beginnings last autumn, I have launched a mini-series about some things I have learned since publishing The Idea of Economic Complexity in 1984. Had I known at the beginning what to expect, I would have announced a series, Complexity Revisited. I do so now.

This week is the fourth installment, counting the first piece – about the 700-year wage and price index of Sir Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins – that triggered the rest. There will be four more, eight in all. Each piece subsequent to the first is connected to something I discovered later, in the witings of Joseph Schumpeter, Charles Kindleberger, Allyn Young, Steven Shapin and Simon Schafer, Nicholas Kaldor, Hendrik Houthakker, and Thomas Stapleford.

What’s the point? It all has to do with the nature of money – how we control it, how it is accumulated, saved and disbursed. Banking is already thoroughly digitized; the digitalization of money itself looms in the future. It makes sense to go back to first principles. These have to do with central banking, it turns out, perhaps the least understood of major modern institutions of governance.

The need here to think matters through, at least a little, arose in connection with other projects underway, large and small. I don’t apologize for having undertaken the series. I’ve done it twice before over the years, each time with good results. But there is something about the weekly column that wants to stay close to the news, especially in these turbulent times. I can confidently promise not to do it again. Back to the news next month.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

— Photo by Acabashi

David Warsh: Nobel economics prize committee needs to look at the lessons of the 2008 crisis

Lehman Brothers headquarters in New York before the firm’s bankruptcy in September 2008 sent the world into the worst financial panic since the Great Depression.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a substantial responsibility the government of Sweden licensed when, in the 1960s, it gave its blessing to the creation of a prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel, to be administered by Nobel Foundation and awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. That bold action wasn’t easy, but it was as easy as it would get.

The Cold War smoldered ominously between two very different systems, “capitalist” and “communist.” In the West, the prestige of the Keynesian revolution was at its height, compared by some historians of science to the Darwinian, Einsteinian, Freudian and quantum revolutions. And the Science Academy possessed seventy-five years of experience as administrators of the physics and chemistry awards that were among the five prizes mandated by Nobel’s handwritten will.

Since 1969, when the first economics prize was awarded, the committee that oversees it has done pretty well, at least in the judgment of those who have followed the program closely. The Nobel system has imposed a narrative order on various developments since the 1940s in an otherwise fractious profession, often by recognizing its close neighbors. Goodness knows where we in the audience would be without it – still reading Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers, perhaps, first published in 1953, as though nothing since had happened.

Now, however, the Nobel Prize in economic sciences is facing a crucial test. The authorities need to give a prize to clarify understanding inside and outside the profession of the events of 2008, when emergency lending and institutional restructuring by the world’s central banks halted a severe financial panic. What might have turned into a second Great Depression was thus averted. Governments’ responsibilities as lenders of last resort were the heart of the issue over which Keynesians and Monetarists jousted for seventy-five years after 1932.

Either the Swedes have something to say about what happened in 2008, not necessarily this year, but soon, or else they don’t. Their discussions are well underway. The credibility of the prize is at stake.

The Nobel committees that administered the prizes in physics and chemistry faced similar problems in their early years. When the first prizes were awarded, in 1901, well-established discoveries dating from the 1890s made the decisions relatively noncontroversial – the discovery of x-rays, radioactivity, the presence of inert gases in the atmosphere, and the electron. Foreign scientists were invited to make nominations; Swedish experts on the small committees, several of them quite cosmopolitan, made the decisions. The members of the much larger academy customarily accepted their recommendations.

But a pair of scientific revolutions, in quantum mechanics and relativity theory, soon generated “problem candidacies” that took several years to resolve. Max Planck, first seriously considered in 1908 for his discovery of energy quanta, was final recognized in 1918. Albert Einstein, first nominated in 1910 for his special relativity theory, was recognized only in 1921, and then for his less important work on the photo-voltaic effect.

It is thanks to Elisabeth Crawford, the Swedish historian of science who first won permission to study the Nobel archive, that we know something about behind-the-scenes campaigns among rival scientists that underlay these decisions. Overlooked altogether may have been the significance of the work of Ludwig Boltzmann, who committed suicide in 1906.

The economics committee has what it needs to make a decision about 2008. The Swedish banking system suffered a similar crisis in the early Nineties and dealt with it in a similar way. Fifteen years later, Swedish economists paid close attention to what was happening in New York and Washington,

In 2017, in cooperation with the Swedish House of Finance, the committee organized a symposium on money and banking, at which the leading interpreters of the 2008 crisis contributed discussions. (You can see here for yourself some of the sessions from that two-and-half day affair, but good luck making sense of the program. That’s what the committee exists to do – after the fact.)

A previous symposium, in 1999, considered economics of transition from planned economies, and wisely steered off. No such inquiry was required to arrive the sequence of prizes that interpreted the disinflation that followed the Volcker stabilization – Robert Lucas (1995), Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott (2004), Thomas Sargent and Christopher Sims (2012) – a process that unfolded more slowly and less certainly than the intervention of 2008.

The money and banking prize should be understood as fundamentally a prize for theory. For all the talk in the last few years about the rise of applied economics, the Nobel narrative, at least as I understand it, has emphasized mainly surprises of various sorts that have emerged from fresh applications of theory, in keeping with Einstein’s dictum that it is the theory that determines what we can observe.

Some of these applications may have reached dead ends, leading to new twists and turns. The advent of cheap, powerful computer and designer software in the Nineties handed economists a power new tool, and two recent prizes have reflected the uses to which the tools have been put – devising randomized controlled tests of economic policies, and drawing conclusion from carefully-studied “natural experiments.” But otherwise “the age of the applied economist” may be mainly a marketing campaign for a generation of young economists eager to advance their careers. It won’t be an age in economic science until the Nobel timeline says it is.

As a journalist, I’ve covered the field for forty years. My impression is that many exciting developments have occurred in that time that have not yet been recognized, some of them quite surprising, many of them reassuring. As the Nobel view of the evolution of the field is revealed in successive Octobers, the effect may be to buttress confidence in the field and diminish skepticism about its roots – or not. As for natural experiments, it is hard to beat the events of 2008. The Swedes have many nominations. What they must do now is decide.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

David Warsh: Pinning things down using history

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In Natural Experiments of History, a collection of essays published a decade ago, editors Jared Diamond and James Robinson wrote, “The controlled and replicated laboratory experiment, in which the experimenter directly manipulates variables, is often considered the hallmark of the scientific method” – virtually the only approach employed in physics, chemistry, molecular biology.

Yet in fields considered scientific that are concerned with the past – evolutionary biology, paleontology, historical geology, epidemiology, astrophysics – manipulative experiments are not possible. Other paths to knowledge are therefore required, they explained, methods of “observing, describing, and explaining the real world, and of setting the individual explanations within a larger framework “– of “doing science,” in other words.

Studying “natural experiments” is one useful alternative, they continued – finding systems that are similar in many ways but which differ significantly with respect to factors whose influence can be compared quantitatively, aided by statistical analysis.

Thus this year’s Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences recognizes Joshua Angrist, 61, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; David Card, 64, of the University of California, Berkeley; and Guido Imbens, 58, of Stanford University, “for having shown that natural experiments can answer central questions for society.”

Angrist, burst on the scene in in 1990, when “Lifetime Earnings and the Vietnam Era Draft Lottery: Evidence from Social Security administrative records” appeared in the American Economic Review. The luck of the draw had, for a time, determined who would be drafted during America’s Vietnam War, but in the early 1980s, long after their wartime service was ended, the earnings of white veterans were about 15 percent less than the earnings of comparable nonveterans, Angrist showed.

About the same time, Card had a similar idea, studying the impact on the Miami labor market of the massive Mariel boatlift out of Cuba, but his paper appeared in the less prestigious Industrial and Labor Relations Review. Card then partnered with his colleague, Alan Krueger, to search for more natural experiments in labor markets. Their most important contribution, a careful study of differential responses in nearby eastern Pennsylvania to a minimum-wage increase in New Jersey, appeared as was Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage (Princeton, 1994). Angrist and Imbens, meanwhile, mainly explored methodological questions.

Given the rule that no more than three persons can share a given Nobel prize, and the lesser likelihood that separate prizes might be given in two different years, Krueger’s tragic suicide, in 2019, rendered it possible to cite, in a single award, Card, for empirical work, and Angrist and Imbens, for methodological contributions.

Princeton economist Orley Ashenfelter, who, with his mentor Richard Quandt, also of Princeton, more or less started it all, told National Public Radio’s Planet Money that “It’s a nice thing because the Nobel committee has been fixated on economic theory for so long, and now this is the second prize awarded for how economic analysis is now primarily done. Most economic analysis nowadays is applied and empirical.” [Work on randomized clinical trials was recognized in 2019.]

In 2010 Angrist and Jörn-Staffen Pischke described the movement as “the credibility revolution.” And in the The Age of the Applied Economist: the Transformation of Economics since the 1970s. (Duke, 2017), Matthew Panhans and John Singleton wrote that “[T]he missionary’s Bible today is less Mas-Colell et al and more Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion (Angrist and Pischke, Princeton, 2011)

Maybe so. Still, many of those “larger frameworks” must lie somewhere ahead.

“History,’’ by Frederick Dielman (1896)

That Dale Jorgenson, of Harvard University, would be recognized with a Nobel Prize was an all but foregone conclusion as recently as twenty years ago. Harvard University had hired him away from the University of California at Berkeley in 1969, along Zvi Griliches, from the University of Chicago, and Kenneth Arrow, from Stanford University (the year before). Arrow had received the Clark Medal in 1957, Griliches in 1965; Jorgenson was named in 1971. “[H]e is preeminently a master of the territory between economics and statistics, where both have to be applied in the study of concrete problems.” said the citation. With John Hicks, Arrow received the Nobel Prize the next year.

For the next thirty years, all three men brought imagination to bear on one problem after another. Griliches was named a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association in 1994; he died in 1999. Jorgenson, named a Distinguished Fellow in 2001, began an ambitious new project in 2010 to continuously update measures of output and inputs of capital, labor, energy, materials and services for individual industries. Arrow returned to Stanford in 1979 and died in 2017.

Call Jorgenson’s contributions to growth accounting “normal science” if you like – mopping up, making sure, improving the measures introduced by Simon Kuznets, Ricard Stone, and Angus Deaton. It didn’t seem so at the time. The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on.

xxx

Where are the women in economics, asked Tim Harford, economics columnist of the Financial Times the other day. They are everywhere, still small in numbers, especially at senior level, but their participation is steadily growing. AEA presidents include Alice Rivlin (1986); Anne Krueger (1996); Claudia Goldin (2013); Janet Yellen (2020); Christina Romer (2022), and Susan Athey, president elect (2023). Clark medals have been awarded to Athey (2007), Esther Duflo (2010), Amy Finkelstein (2012), Emi Nakamura (2019), and Melissa Dell (2020).

Not to mention that Yellen, having chaired the Federal Reserve Board for four years, today is secretary of the Treasury; that Fed governor Lael Brainerd is widely considered an eventual chair; that Cecilia Elena Rouse chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers; that Christine Lagarde is president of European Central Bank; and that Kristalina Georgieva is managing director of the International Monetary Fund, for a while longer, at least.

The latest woman to enter these upper ranks is Eva Mörk, a professor of economics at Uppsala University, apparently the first female to join the Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences that recommends the Economics Sciences Prize, the last barrier to fall in an otherwise egalitarian institution. She stepped out from behind the table in Stockholm last week to deliver a strong TED-style talk (at minutes 5:30-18:30 in the recording) about the whys and wherefores of the award, and gave an interesting interview afterwards.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Economic models and engineering

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The best book about developments in the culture of professional economics to appear in the last quarter century is, in my opinion, The World in the Model: How Economists Work and Think (Cambridge, 2012), by Mary S. Morgan, of the London School of Economics and the University of Amsterdam. The best book of the quarter century before that is, again, according to me, An Engine, Not a Camera: How Models Shape Financial Markets (MIT, 1997), by Donald MacKenzie, of the University of Edinburgh.

Both books describe the introduction of mathematical models in the years beginning before World War II. Both consider how the subsequent use of those techniques has changed how economics is done by economists. Morgan’s book is about the kinds of models that economists devise experimentally, not those that interest MacKenzie most, models designed to be tested against the real world. A deft cover illustrates Morgan’s preoccupation, showing the interior of a closed room with only a high window. On the floor of the room are written graphic diagram of supply and demand. The window opens only to the sky outside, above the world itself, a world the model-builder cannot see. The introduction of statistical inference to economics she dealt with in The History of Econometric Ideas (Cambridge, 1990).

I remember the surprise I felt when I first read Morgan’s entry “Economics” in The Cambridge History of Science Volume 7: The Modern Social Sciences (Cambridge, 2003). She described two familiar wings of economics, often characterized in the 19th Century as “the science of political economy” and “the art of economic governance.” Gradually in that century they were relabeled “positive” economics (the way it is, given human nature) and “normative” economics (the way it ought to be).

Having practiced economics in strictly literary fashion during the modern subject’s first century, Morgan continued, economists in the second half of the 19th Century began adopting differential calculus as a language to describe their reasoning. In the 20th Century, particularly its second half, the two wings have been firmly “joined together” by their shared use of “a set of technologies,” consisting mainly of mathematics, statistics and models. Western technocratic economics, she wrote, had thereby become “an engineering science.”

I doubted at the time that it was especially helpful to think economics that way.

Having read Economics and Engineering: Institutions, Practices, and Cultures (2021, Duke), I still doubt it. That annual conference volume of the journal History of Political Economy appeared earlier this year, containing 10 essays by historians of thought, with a forward by engineering professor David Blockley, of the University of Bristol, and an afterword by Morgan herself. Three developments – the objectification of the economy as a system; the emergence of tools, technologies and expertise; and a sense of the profession’s public responsibility – had created something that might be understood as “an engineering approach” to the economy and in economics, writes Morgan. She goes on to distinguish between two modes of economic engineering, start-fresh design and fix-it-up problem-solving, noting that enthusiasm for the design or redesign of whole economies and/or vast sectors of them had diminished in the past thirty years.

It’s not that the 10 essays don’t make a strong case for Morgan’s insights about various borrowings from engineering that have occurred over the years: in particular, Judy Klein, of Mary Baldwin University, on control theory and engineering; Aurélien Saïdi, of the University of Paris Nanterre, and Beatrice Cherrier, of the University of Cergy Pontoise and the Ecole Polytechnique, on the tendencies of Stanford University to produce engineers; and William Thomas, of the American Institute of Physics, on the genesis at RAND Corp. of Kenneth Arrow’s views of the economic significance of information.

My doubts have to do with whether the “science” of economics and the practice of its application to social policy have indeed been in fact been “firmly joined” together by the fact that both wings now share a common language. I wonder whether more than a relatively small portion of what we consider to be the domain of economic science is sufficiently well understood and agreed-upon by economists themselves as to permit “engineering” applications.

Take physics. In the four hundred years since Newton many departments of engineering have been spawned: mechanical, civil, electrical, aeronautical, nuclear, geo-thermal. But has physics thereby become an engineering science? Did the emergence of chemical engineering in the 1920s change our sense of what constitutes chemistry? Is biology less a science for the explosion of biotech applications that has taken place since the structure of the DNA molecule was identified in 1953? Probably not.

Some provinces of economics can be considered to have reached the degree of durable consensus that permits experts to undertake engineering applications. I count a dozen Nobel prizes as having been shared for work that can be legitimately described as economic engineering: Harry Markowitz, Merton Miller and William Sharpe, in 1990, for “pioneering work in financial economics”; Robert Merton and Myron Scholes, in 1997, “for a new method to determine the value of derivatives”; Lloyd Shapley and Alvin Roth, in 2012, “for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design”: Abajit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer, in 2019, for “their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”; and Paul Milgrom and Robert Wilson, in 2020, for “improvements to auction theory and inventions of new auction formats.”

This is where sociologist Donald McKenzie comes in. In An Engine Not a Camera, he describes the steps by which, in the course of embracing the techniques of mathematical modeling, finance theory had become “an active force transforming its environment, not a camera, passively recording it,” but an engine, remaking it. When market traders themselves adopted models from the literature, the new theories brought into existence the very transactions of which abstract theory had spoken – and then elaborated them. Markets for derivatives grew exponentially. Such was the “performativity” of the new understanding of finance. After all, writes Morgan in her afterword, hasn’t remaking the world been the goal of economic-engineering interventions all along?

Natural language has a knack for finding its way in these matters. We speak easily of “financial engineering” and “genetic engineering.” But “fine-tuning,” the ambition of macro-economists in the 1960s, is a dimly remembered joke. The 1942 photograph on the cover of Economics and Engineering – graduate students watching while a professor manipulates a powerful instrument laden with gauges and controls – seems like a nightmare version of the film Wizard of Oz.

John Maynard Keynes memorably longed for the day when economists would manage to get themselves thought of as “humble, competent people on a level with dentists.” Nobel laureate Duflo a few years ago compared economic fieldwork to the plumbers’ trade. “The scientist provides the general framework that guides the design…. The engineer takes these general principles into account, but applies them to a specific situation…. The plumber goes one step further than the engineer: she installs the machine in the real world, carefully watches what happens, and then tinkers as needed.”

The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act that became law last week, with its myriad social programs, is not founded on what “the science” says. It is an intuition, an act of faith. Better to continue to refer to most economic programs as “strategies” and “policies” instead of “engineering,” and consider effective implementations to be artful work.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared

Copyright 2021 by David Warsh, proprietor

David Warsh: Blame political choices, not economists, for today's mess

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A couple of recent books by well-regarded journalists – Binyamin Appelbaum and Nicholas Lemann, have blamed economists for the current state of the world. Reviewing these in Foreign Affairs last week, the peripatetic New York University economist Paul Romer embraced the authors’ judgments and added his own.

Having lost track of the distinction between positive and normative economics (is vs. ought), the profession has come to think of itself and be thought of by others as a tribe of philosopher-kings, Romer wrote. Citing the OxyContin epidemic and the 2008 financial crisis, he summed up in “The Dismal Kingdom”

Simply put, a system that delegates to economists the responsibility for answering normative questions may yield many reasonable decisions when the stakes are low, but it will fail and cause enormous damage when powerful industries are brought into the mix. And it takes only a few huge failures to offset whatever positive difference smaller, successful interventions have made.

A third book, Where Economics Went Wrong: Chicago’s Abandonment of Classical Liberalism, by economists David Colander and Craig Freedman (Princeton, 2019), mentioned by Romer, hasn’t received as much attention. It sets out the case in detail, with clarity and in depth. A fourth book, In Search of the Two-Handed Economist: Ideology, Methodology and Marketing in Economics, by Freedman (Palgrave 2016), offers the deepest dive of all, but hardly ever comes up outside of professional circles (where it is often discussed with hand-rubbing, lip-smacking enthusiasm, thanks to the extensive interviews it contains).

Accoding to Colander and Freedman, economics began to go off-course in the 1930s, when it embraced an ambitious new program that came to be known as “welfare economics,” replacing the “classical liberalism” of John Stuart Mill. The new framework developed slowly, led by John Hicks and Abba Lerner at the London School of Economics, Arthur Pigou at Cambridge University, and Paul Samuelson at Harvard University and The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but in the 1950s, seemed to virtually take over the profession, coming to be associated simply with the macroeconomics of John Maynard Keynes.

The new framework was conducted with mathematical and statistical models instead of arguments about moral philosophy and curiosity about, even respect for, existing institutions. Believing itself to be an understanding superior to what had gone before, This new approach – now simply “the new economics,” abandoned the traditional firewall between science and policy.

Irked and, for a time, flummoxed by welfare economics’ assertiveness, especially in its Keynesian form, young economists from all over congregated at the University of Chicago, starting in 1943. Led by Milton Friedman, George Stigler and Aaron Director, they began to look for flaws in Keynesian doctrines, which they viewed as “a Trojan horse being used to advance statist ideology and collectivist ideals,” Colander and Freeland say.

Secure in their belief that markets could, to a considerable extent, take care of themselves, thanks to the powerful solvent of competition, the Chicagoans responded to normative science with more stringent normative science. They devised an alternative “scientific” pathway that would lead to their intuited laissez-faire vision.

“Because of their impressive rhetorical and intuitive marketing skills, the Chicago economists eventually managed to engineer a successful partial counterrevolution against [the] general equilibrium welfare economic framework,” write Colander and Freedman. But embracing cost-benefit analysis required abandoning the tenets of debate focused on judgements and sensibilities – “argumentation for the sake of heaven,” as the authors prefer to put it

So what does a present-day hero of classical liberalism look like? Colander and Freedman cite six well-known exemplars: Edward Leamer, who wrote a classic 1983 critique of scientific pretension, “Taking the Con Out of Econometrics”; Ariel Rubinstein, a distinguished game theorist who describes models as no more compelling than economic fables; Dani Rodrik, a rigorous trade theorist who asked as long ago as 1997, Has Globalization Gone Too Far?; Nobel laureate Alvin Roth, who likens the role of many economist to that of an engineer; Amartya Sen, another laureate, recognized for his “scientific” work on collective decision-making but honored for his policy work on the development of capabilities; and Romer, another laureate perhaps better known for his biting criticism of “mathiness,” akin to “truthiness,” among leaders of the profession.

All are excellent economists. But almost certainly it was not the economics profession that led the world down a garden path to its present state of discombobulation. In his Foreign Affairs review, Romer asserts,

For the past 60 years, the United States has run what amounts to a natural experiment designed to answer a simple question: What happens when a government starts conducting its business in the foreign language of economists? After 1960, anyone who wanted to discuss almost any aspect of US public policy – from how to make cars safer to whether to abolish the draft, from how to support the housing market to whether to regulate the financial sector – had to speak economics. Economists bring scientific precision and rigor to government interventions, the thinking went, promised expertise and fact-based analysis.

Far more persuasive were the natural experiments conducted in the language of the Cold War. They include the rise of Japan in the global economy; the decision of China’s leaders to follow its neighbors’ example and join the global market system; the slow decline and rapid final collapse of the Soviet empire; the financial-asset boom that followed Western central bankers’ success in quelling inflation; the globalization that accompanied a burst of “deregulation”; the integration that accompanied the invention of computers, satellites, and the Internet; and the escape from extreme poverty of 1.1 billion people, a seventh of the world’s population.

Rivalries among nations were far more influential in precipitating these changes than were contests among Keynesians and Monetarists, even their magazines and television debates. Political choices produced the present world – grass roots, top-down, and everywhere in between. Economists scrambled to keep up.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

© 2020 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

David Warsh: A lyrical look at the rise and fall of U.S. economic growth

SAN FRANCISCO

It was just two years ago that Thomas Piketty directed economists’ attention to rapidly rising degrees of inequality with his weighty tome Capital in the Twenty First Century (Harvard, 2014). We know too much to return to the single-minded preoccupation with distribution exemplified by 19th Century pioneers such as Malthus, Ricardo, and Marx. A series of industrial revolutions has seen to that.

The growth of knowledge has made room on the planet for the lives of billions of persons, and dramatically raised longevity and living standards among them around the world. But what if the rate of improvement has slowed? The first installment in the dystopian film saga The Hunger Games rolled out four years ago.

Piketty is right, of course, that institutions and policies are central to whatever happens next, and that we require a much clearer picture of the distribution of income and wealth to guide social decision-making in the future. That was one of the reasons the Swedes awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics last autumn to Angus Deaton, of Princeton University. As Deaton noted in his prize lecture, “In a world in which you work entirely in averages, if you look at the macro economy, things like inequality and poverty are simply not legible.” Without the details of individual choices, they disappear. “Even if you are only interested in the aggregate economy, distribution clearly matters for aggregate economic activity, and certainly for any serious analysis of well-being.”

Hence the depictions of Deaton working with a microscope, devising comparisons of, for instance, what it means to subsist on dollar a day. It’s a matter of “honest scorekeeping,” he says, among competing measures designed to improve individual well-being.

Some of them work and some don’t. Piketty’s empirical work, with Emmanuel Saez, of the University of California at Berkeley, and Sir Anthony Atkinson, of Nuffield College, Oxford, on the concentration of wealth in 19th- and 20th Century societies has set a high standard. Nicholas Bloom, of Stanford University, made headlines at a session of the meetings of the American Economic Association here with a new study, Firming Up Inequality, extending the analysis to industrial organization. Individuals’ inequality with their coworkers has changed little over the past three decades, he and his co-authors found; it is inequality among firms that is increasing. Workers with good corporate jobs therefore experience little growing inequality.

But as Philippe Aghion, a former Harvard professor who last year bested Piketty in competition for an appointment to a permanent professorship at the College de France, pointed out in a talk at the meetings, it is by no means clear that the potential for growth has been exhausted. Pro-growth policies remain important; they must take account of several different yardsticks of inequality, not just concentrations at the top, but measures of social mobility as well. Innovation is indisputably a source of top income inequality, Aghion said, but it differs from others sources: for example, consider the difference between Steve Jobs, who helped create smart phone, and Carlos Slim, who gained control of the cellular market through political influence, first in Mexico, and then in 18 other countries. Aghion and several coauthors spelled out the argument for fostering innovative growth last summer in an article for Vox EU.

For that reason, it seems to me that the most important development at the meetings was the appearance of another big book, in many ways the perfect complement to Piketty’s treatise. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War (Princeton, 2016), by Robert J. Gordon, of Northwestern University, also arrived with a intimidating thud: Rise and Fall weighs in at 762 pages, vs. 685 pages for Capital in the Twenty-first Century. (My enthusiasm for his research program played a minor role in his expanding an article into the book.)

Not that Gordon’s book is heavy-going. It’s just the opposite. A poet of the Sears, Roebuck catalog for his chapter in a 1980 National Bureau of Economic Research volume, The Measurement of Durable Goods Prices, Gordon went on to co-edit a landmark NBER volume, The Economics of New Goods, in 1996. (The book included an essay by William Nordhaus, of Yale University, on the historic costs of lighting a room at night that is as close to a decisive experiment as is to be found in all of economics.) The inspiration for the present book, Gordon writes, dates from a chance encounter in a bed-and-breakfast with Otto Bettmann’s 1974 book, The Good Old Days –They Were Terrible. Bettmann, a German émigré, founded the Bettmann Archive of historically interesting photographs, in 1936. Gordon has boiled down the story to analytic narrative.

He divides the 15 core chapters into two periods, 1870-1940 and 1940-2015, speedup in one era and slowdown in another, hence “one big surge,” the sobriquet by which Gordon’s thesis has been known since it first appeared as a journal article, in 2000. The great inventions of the past could happen only once, he argued then. Wondrous as they are, he says, microprocessors and the packet-switching of the Internet do nor rival the invention of electricity, the internal-combustion engine, or flight. (Many young economists are unconvinced by this last claim.)

Thus chapters in the first period include “The Starting Point: Life and Work in 1870”; “What They Ate and Wore and Where They Bought It”: “The American Home: from Dark and Isolated to Bright and Networked”; ”Motors Overtake Horses and Rail: Inventions and Incremental Improvements”; “From Telegraph to Talkies: Information, Communication, and Entertainment”; “Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Illness and Early Death”; “Working Conditions on the Job and at Home”; “Taking and Mitigating Risks: Consumer Credit, Insurance, and the Government.” (I would have mentioned fewer titles except they convey so clearly the argument of the book.)

Chapters after 1940 include “Fast Food, Synthetic Fibers and Split-level Subdivisions: the Slowing Transformations of Food, Clothing and Housing”; “See the USA in Your Chevrolet or from a Plane Flying High Above”; Entertainment and Communications from Milton Berle to the iPhone”; “Computers and the Internet from the Mainframe to Facebook”; “Antibiotics, CT Scans, and the Evolution of Health and Medicine”; and “Work, Youth and Retirement at Home and on the Job.”

In the business end of the book, Gordon trades his role as historian for that of macroeconomist and growth accountant. He reprises his three key papers, including “Inequality and the Other Headwinds: Long-run American Economic Growth Slows to a Crawl,” the essay that gradually grew into the book.

What are these impediments to growth? The first is rapidly growing inequality itself, which Piketty, Saez, and others have documented. With incomes of the bottom 90 percent of the population growing much more slowly than the top ten percent, there simply won’t be enough spending to fuel the growth of median income at more than barely half its historic rate. Rising costs of education and its declining quality constitute a second headwind; demographic factors, chiefly the retirement of Baby Boomers, are a third; bourgeoning government debt is a fourth. Lesser frictions include globalization, global warming, and industrial pollution.

Through a relentless process of adding-up and subtraction, Gordon concludes that, for decades, “the future growth of real median income per person will be barely positive and far below the rate enjoyed by generations of Americans dating back to the 19th Century.” He adds a brief postscript describing measures that might boost productivity and accelerate somewhat the rate of future growth: a more equitable and efficient tax system; a better education system; less incarceration; drug legalization; more immigration; a federal fiscal reckoning that today seems quite out of reach.

Recently Gordon has been bogged down in debates with techno-optimists, the MIT duo of Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee; and Gordon’s Northwestern colleague, Joel Mokyr, a distinguished historian of technology. “Nobody debates the headwinds. Instead they debate technical progress,” Gordon laments.

The meetings, at least, provoked a spirited discussion among a panel of distinguished economic historians: Gregory Clark, of the University of California at Davis; Nicholas Crafts, of the University of Warwick; Benjamin Friedman, of Harvard University;and Noam Yuchtman, of the University of California at Berkeley Haas School of Business, a proxy for James Robinson, of the University of Chicago, who was unable to attend.

The real debate is with the assumptions embedded in various congressionally-mandated forecasts of future growth. What’s the difference between the official 2.2 percent growth in the Budget Data Projections of the Congressional Budget Office and Gordon’s estimate of 0.5 percent? The difference between halcyon days and sustained turmoil. For the present, at least, growth accounting dominates the center ring of policy economics. The taboo on facing up to its implications hangs over the presidential primaries.

Richard Thaler, of the University of Chicago, Booth School of Business, gave the presidential address; president-elect Robert Shiller, of Yale University, organized the meetings. Jeremy Campbell, of Harvard University, gave the Ely Lecture, “Restoring Rational Choice: the Challenge of Consumer Finance.” Bengt Holmström, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, gave the Joint AEA/AFA Luncheon Address, “Why Are Money Markets Different?”, with Patrick Bolton, of Columbia University Graduate School of Business presiding. Some 13,300 members of more than 50 Allied Social Science Associations registered for the meetings, a record.

David Warsh, proprietor of economicprincipals.com, is a long-time financial journalist and economic historian (and colleague many years ago of New England Diary’s overseer, Robert Whitcomb, at The Wall Street Journal.