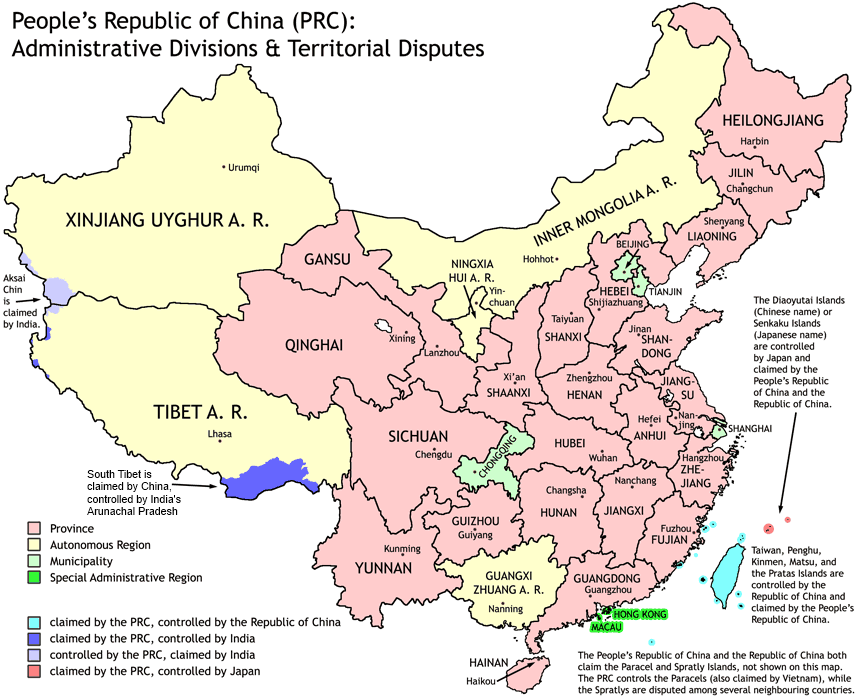

David Warsh: Competing with expansionist China while managing internal threats to our democracy

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I have, at least since 1989, been a believer that competition between the West and China is likely to dominate global history for the foreseeable future. By that I mean at least the next hundred years or so.

I am a reluctant convert to the view that the contest has arrived at a new and more dangerous phase. The increasing belligerence of Chinese foreign policy in the last few years has overcome my doubts.

It was a quarter century ago that I read World Economic Primacy: 1500-1990, by Charles P. Kindleberger. I held no economic historian in higher regard than CPK, but I raised an eyebrow at his penultimate chapter, “Japan in the Queue?” His last chapter, “The National Life Cycle,” made more sense to me, but even then wasn’t convinced that he had got the units of account or the time-scales right.

The Damascene moment in my case came last week after I subscribed to Foreign Affairs, an influential six-times-a-year journal of opinion published by the Council on Foreign Relations. Out of the corner of my eye, I had been following a behind-the-scenes controversy, engendered by an article in the magazine about what successive Republican and Democratic administrations thought they were doing as they engaged with China, starting with the surprise “opening” engineered by Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger in 1971. I subscribed to Foreign Affairs to see what I had been missing.

In 2018, in “The China Reckoning,’’ the piece that started the row, foreign- policy specialists Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner had asserted that, for over fifty years, Washington had “put too much faith in its power to shape China’s trajectory.” The stance had been previously identified mainly with then-President Donald Trump. Both Campbell and Ely wound up in senior positions in the Biden administration, at the White House and the Pentagon.

In fact the proximate cause of my subscription was the most recent installment in this fracas. To read “The Inevitable Rivalry,’’ by John Mearsheimer, of the University of Chicago, an article in the November/December issue of the magazine, I had to pay the entry rate. His essay turned out to be a dud.

Had U.S. policymakers during the unipolar moment thought in terms of balance-of-power politics, they would have tried to slow Chinese growth and maximize the power gap between Beijing and Washington. But once China grew wealthy, a U.S.-Chinese cold war was inevitable. Engagement may have been the worst strategic blunder any country has made in recent history: there is no comparable example of a great power actively fostering the rise of a peer competitor. And it is now too late to do much about it.

Mearsheimer’s article completely failed to persuade me. Devotion to the religion he calls “realism” leads him to ignore two hundred years of Chinese history and the great foreign-policy lesson of the 20th Century: the disastrous realism of the 1919 Versailles Treaty that ended World War I and led to World War II, vs. the pragmatism of the Marshall Plan of 1947, which helped prevent World War III. There is no room for moral conduct is his version of realism. It is hardball all the way.

My new subscription led me to the archives, and soon to “Short of War,’’ by Kevin Rudd, which convinced me that China’s designs on Taiwan were likely to escalate, given President Xi Jinping’s intention to remain in power indefinitely. (Term limits were abolished on his behalf in 2018.) By 2035 he will be 82, the age at which Mao Zedong died. Mao had once mused that repossession of the breakaway island nation of Taiwan might take as long as a hundred years.

Beijing now intends to complete its military modernization program by 2027 (seven years ahead of the previous schedule), with the main goal of giving China a decisive edge in all conceivable scenarios for a conflict with the United States over Taiwan. A victory in such a conflict would allow President Xi to carry out a forced reunification with Taiwan before leaving power—an achievement that would put him on the same level within the CCP pantheon as Mao Zedong.

That led me in turn to “The World China Wants,’’ by Rana Mitter, a professor of Chinese politics and history at Oxford University. He notes that, at least since the global financial crisis of 2008, China’s leaders have increasingly presented their authoritarian style of governance as an end in and of itself, not a steppingstone to a liberal democratic system. That could change in time, she says.

To legitimize its approach, China often turns to history, invoking its premodern past, for example, or reinterpreting the events of World War II. China’s increasingly authoritarian direction under Xi offers only one possible future for the country. To understand where China could be headed, observers must pay attention to the major elements of Chinese power and the frameworks through which that power is both expressed and imagined.

The ultimate prize of my Foreign Affairs reading day was “The New Cold War,’’ a long and intricately reasoned article in the latest issue by Hal Brands, of Johns Hopkins University, and John Lewis Gaddis, of Yale University, about the lessons they had drawn from a hundred and fifty years of competition among great powers. I especially agreed with their conclusion:

As [George] Kennan pointed out in the most quoted article ever published in these pages, “Exhibitions of indecision, disunity and internal disintegration within this country” can “have an exhilarating effect” on external enemies. To defend its external interests, then, “the United States need only measure up to its own best traditions and prove itself worthy of preservation as a great nation.”

Easily said, not easily done, and therein lies the ultimate test for the United States in its contest with China: the patient management of internal threats to our democracy, as well as tolerance of the moral and geopolitical contradictions through which global diversity can most feasibly be defended. The study of history is the best compass we have in navigating this future—even if it turns out to be not what we’d expected and not in most respects what we’ve experienced before.

That sounded right to me. Worries exist in a hierarchy: leadership of the Federal Reserve Board; the U.S. presidential election in 2024; the stability of the international monetary system; arms races of various sorts; climate change. Subordinating all these to the China problem will take time.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

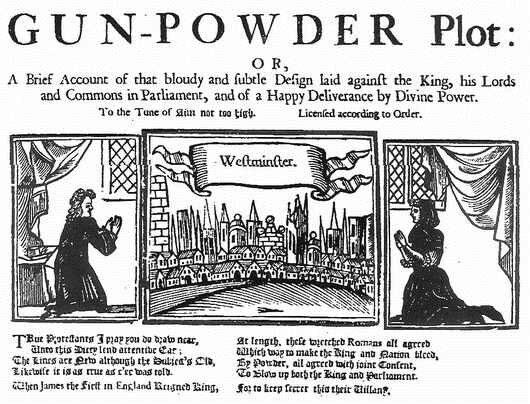

David Warsh: Aaron Burr, the Gunpowder Plot and our current scoundrel-in-chief

Vice President Aaron Burr in 1802

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Donald Trump has begun appearing in the rear-view mirror. I have compared Trump to Aaron Burr, the scoundrel who sought to overturn the 1800 presidential election in the early days of the Republic. Hit this link for an explanation of what he did.

Later, starting in 1804, Burr sought to invent around U.S. elections altogether, hoping to foment a breakaway-nation that he could govern in the Spanish Southwest.

No other episode in American history comes close. But after following news about the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol, I’m inclined to believe that the history of England offers a more illuminating comparison. I’ve been thinking about Guy Fawkes and the 17th Century Gunpowder Plot.

The background was the Protestant Reformation, which had begun in Germany, in 1517, with Martin Luther. Starting in 1533, King Henry VIII withdrew Britain its allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church. Catholics, especially Jesuit priests, had a hard time of it under Henry’s daughter Queen Elizabeth I. Elizabeth’s Catholic cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, was executed for treason in 1587.

Elizabeth died childless, in 1603, without having named an heir. Queen Mary’s son, Elizabeth’s nephew, peacefully acceded to the throne as James I of England and James VI of Scotland. But repression of Catholics continued, and in 1605 a group of English Catholics plotted to blow up the House of Lords during the opening of Parliament, on Nov. 5. Betrayed by a letter of seemingly mysterious provenance, one of the plotters, Guy Fawkes, was discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder in the basement the night before, quite enough to demolish the building. The plotters were captured and, one way or another, put to death, including some Catholic clergy linked to the plot.

The world was smaller then. Passions ran deeper. Globalization had only just begun. But it is hard to think of any other episode in Anglo-American history whose rhetorical aim resembled more closely that of the mob that descended on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, having been dispatched on their mission by President Trump.

One group of skirmishers came within seconds of sighting Vice President Pence as he, along with his wife and daughter, was spirited out of the Senate chamber and into a hideaway, according to a Jan. 16 story in The Washington Post. The gunpowder plotters intended to kill King James and install his nine-year-old daughter on the throne as Catholic monarch. The Capitol Hill mob vigorously denounced Pence as a traitor for his failure to overturn the presidential-election results. A mock gallows was installed on the western approach to the Capitol.

Persecution of Catholics continued but was mild relative to the century before for the remainder of the reign of James I – he died in 1625 – but anti-Catholic sentiment persisted in England for two centuries, through a not-unrelated civil war and a very-related “Glorious Revolution.”

No one knows what might be the long-term effects of the assault on the Capitol. My hunch is that it will be remembered as thoroughly repugnant and rejected and condemned until it is forgotten. For a higher-resolution characterological account of the Trump story, see “What TV Can Tell Us about How the Trump Show Ends,” by Joanna Weiss. The Trump presidency resembled an antihero drama, Weiss says, more closely than reality TV, the saga of Tony Soprano her chief case in point.

With this emergency behind, I am returning this weekly to my main concern, economics, meanwhile finishing a book on the last hundred years of its textbook versions. As for my plans to shift to the Substack publishing platform, they are postponed; Economic Principals will move at the end of the year, by which time the book will have begun wending its way its way to the press. Luck be a lady this year!

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville, Mass.-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: In the press, a dose of vicarious shock

“Kitty” Genovese

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a famous story from The New York Times in 1964.

37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police; Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector

by Martin Gansberg

For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law‐abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.

Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom lights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he returned, sought her out and stabbed her again. Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead.

That was two weeks ago today. But Assistant Chief Inspector Frederick M. Lussen, in charge of the borough’s detectives and a veteran of 25 years of homicide investigations, is still shocked.

He can give a matter‐of‐fact recitation of many murders. But the Kew Gardens slaying baffles him — not because it is a murder, but because the “good people” failed to call the police.

The story of the killing of Catherine (“Kitty”) Genovese was widely read at the time and admired for decades. It made the reputation of A. M. Rosenthal, the metropolitan editor who caused it to be written and who argued its way onto the front page. Rosenthal’s own gloss on the story, “Thirty-Eight Witnesses,’’ was published within months. He rose rapidly at The Times, to be executive editor in 1977-1987, and for a dozen years after that, a columnist.

It turns out there was a backstory, too. In his book, Rosenthal disclosed how he himself had got the story, from Michael J. Murphy, theNew York City police commissioner, over lunch at Emil’s Restaurant and Bar on Park Row, near City Hall.

“Brother,” the commissioner said, “that Queens story is one for the books.”

Thirty-eight people, the commissioner said, had watched a woman being killed in the “Queens story,” and not one of them had called the police to save her life.

“Thirty-eight?” I asked.

And he said, “Yes, 38. I’ve been in this business a long time, but this beats everything.”

I experienced then that most familiar of newspapermen’s reaction — vicarious shock. This is a kind of professional detachment that is the essence of the trade — the realization that what you are seeing or hearing will startle a reader.

Some readers, including a television police reporter, Danny Meehan, doubted details of the story as soon as it appeared. Over the years various embellishments, inconsistencies, and inaccuracies came to light. In 2004 The Times took account of them. They did not change the essential fact at the heart of the story — a woman had been murdered in the middle of the night in a populous neighborhood, steps from her door. When her killer, Winston Moseley, died in prison, at 82, Robert McFadden summed up in a Times obituary:

The article grossly exaggerated the number of witnesses and what they had perceived. None saw the attack in its entirety. Only a few had glimpsed parts of it, or recognized the cries for help. Many thought they had heard lovers or drunks quarreling. There were two attacks, not three. And afterward, two people did call the police. A 70-year-old woman ventured out and cradled the dying victim in her arms until they arrived. Ms. Genovese died on the way to a hospital.

I thought of the Genovese story because something of the sort happened in my neighborhood earlier this month — but in reverse. On Election Day, a 40-year-old woman was hit and killed in a crosswalk midday by a pickup truck.

Leah Zallman, 40, the mother of two young sons, was on her way home after voting at lunch time. She was the director of research at the Institute for Community Health, a primary-care physician at the East Cambridge Care Center, and an assistant professor of medicine at the Harvard Medical School

Talk about local apathy, at least in the public realm! Television stations reported the accident the day it happened. After that the news was only slowly shared, without details, first by the public school’s parent association, then on community Google groups. The city took a week to acknowledge on its Web site that it had happened. It was 10 days before The Boston Globe took account of it, and then only with a touching remembrance by a columnist free of any details of the accident itself, not even those that had been posted by the city:

An initial investigation suggests that the operator of the vehicle, an employee of the City of Somerville who was on duty at the time but operating their personal vehicle, had been attempting to take a left turn onto Kidder Avenue from College Avenue. They remained on the scene following the crash. Pending the results of an investigation [by the Middlesex District Attorney’s Office and Somerville Police], the employee has been placed on paid administrative leave…. No charges have been filed at this time.

We’ll learn more eventually from the Middlesex County investigation, including the identity of the driver, reported to be a Somerville building inspector, and the circumstances of his day. I wish that there were some local hero, a Rosenthal type, who could document how Zallman’s death could remain on the down-low for more than a week. (City councilors argued the details of the accident with the mayor and his Mobility Department behind the scenes.) Last year, when two women were hit after dark in a crosswalk, one of them killed, by a hit-and run driver less than mile away, it was big news. This time there were no flowers at the site, no other reminder of what happened at the busy crossing, no public outcry, no political outrage, only a lingering sense of shock.

It’s a commonplace that the invention of online search advertising has brought most metropolitan newspapers to their knees. In October the once-mighty Boston Globe reported print circulation of 84,000 daily and 123,000 Sunday, down from 530,000 and 810,000 respectively 20 years ago. The national papers have managed to hold their own so far. That small cities like Somerville, those of 100,000 people or so, haven’t found a way to rejuvenate the provision of local news bodes ill for their public life. With local journalism withering on the vine, we don’t have publicity, hence public outrage, over a traffic death that shouldn’t have happened. We don’t have accountability, either, sufficient to deter careless driving. Pickup trucks, in particular, often seem to confer a dangerous sense of privilege upon their drivers.

To be clear, I don’t think that what Abe Rosenthal did in 1964 was wrong, or wicked, in any sense, though in retrospect its self-aggrandizing subtext is hard to miss. Call it inflated-for-the-good-of-us-all journalism, the presentation of facts spiced with a special sauce of indignation for the purpose of making a point.

The Times had reported Genovese’s murder as an unvarnished matter of fact, when it occurred, in a short item buried deep inside the paper a couple of weeks before. To return to the story with additional facts — police commanders’ indignation – was in line with the performance of the newspaper’s duty to offer occasional moral instruction along with the news. But the embellishment went too far, and tarnished The Times’s most valuable asset, readers’ trust.

Newspapers have traditionally tried to rile up readers in a good cause in the three centuries they have been democracies’ dominant form of public communication. For a wry and affectionate look behind the scenes of inflated-for-the-good-of-us-all journalism at The Times in executive editor Rosenthal’s heyday, find a used copy of I Shouldn’t Be Telling You This, by Mary Breasted. Or rent a copy of Ron Howard’s brilliant 1994 film The Paper.

It seems the case that The Times has practiced more indignation-fueled news recently than usual – its 1619 Project, for example, provoked columnist Bret Stephens’s stinging dissent. The roots are the same as those Rosenthal identified in 1964: the experience of shock in the face of the facts. Rosenthal’s proud claim as editor was that “he kept the paper straight.” Think that is easy in times like these? Occasional large helpings of indignation are better than no news at all.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Getting beyond despair: Three prongs to address climate change

— By Adam Peterson

Flooding caused by Super Storm Sandy in Marblehead, Mass., on Oct. 29, 2012

From economicprincipals.com

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Weighed down by not knowing what to expect of the coronavirus timetable, I spent a day last week reading about climate change. Specifically, I read Three Prongs for Prudent Climate Policy, by Joseph Aldy and Richard Zeckhauser, both of Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

Paradoxically I came away feeling better. Grim though the situation they describe is, theirs is anything but a counsel of despair.

For three decades, advocates for climate change policy have simultaneously emphasized the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and provided unrealistic reassurances of the feasibility of doing so. It hasn’t worked out, say Alby and Zeckhauser.

The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 imposed binding commitments on industrial nations to reduce emissions below 1990 levels in a decade. They exceeded them. Even so, global carbon dioxide emission grew 57 percent over the same ten years, because developing nations hadn’t joined the accord.

So the Paris Agreement of 2015 established “pledge and review” commitments by from virtually every nation in the world, designed to prevent warming of more than 2 degrees centigrade by 2030. But even if every country honors its pledge, the policy is unlikely to succeed in meeting the target, say Aldy and Zeckhauser,

That’s because what’s already in the atmosphere is a stock, not a flow. From the pre-industrial period to 1990, carbon dioxide concentration increased by about 75 parts per million. Since 1990, CO2 has increased by another 55 parts per million, and despite the agreements, the rate of increase is apparently accelerating.

Meanwhile, global temperature have increased around half a degree centigrade in the last 30 years. They are likely to rise faster in the years ahead. Storms, droughts, floods, fires, melting will increase. Mass migrations in response to these weather events have barely begun.

So, the authors say, after 30 years of single-minded stress on emission reductions in climate change discourse, two other policy prongs are urgently needed.

One of these headings, adaptation, is well-known and uncontroversial, except that it costs a lot in more complicate applications than in simple adjustments. Moving heating plants from basements to upper stories so that equipment is not damaged by flooding is simple and relatively cheap. Sea barriers and storm gates to protect coastal cities are another. The sea wall to protect the Venice lagoon is almost finished, but the Army Corps of Engineers plan to protect New York City would take 25 years to construct.

The other strut, amelioration, is considerably less discussed, mainly for fear of the ease with which the remedy may be embraced, once the cost differences are better understood. “Solar radiation management” means putting a sunscreen into the sky – most likely sulfur particles injected into the upper atmosphere by specially built airplanes. Major volcanic eruptions over the centuries have proven that the principle will work, though myriad details of its practical application are hazy. What’s clear is that so-called “geo-engineering” would cost considerably less than emissions reduction or adaptation, especially if time were of the essence.

The only place I see radiation management brought up regularly in the things I read is in Holman Jenkins’s twice-a-week column in the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal. The other day Jenkins noted Amazon’s Jeff Bezos’s intention to spend $10 billion to fight climate change. Don’t spend it touting nuclear power, Jenkins advised; Bill Gates is already working on that. And never mind carbon taxation; that must come, if it comes, from the Left. Instead, why not atmospheric aerosol research?

Right though Jenkins may be about the possibilities of solar-radiation mitigation, he is preaching to those ready to be converted. That’s why I was interested in the Aldy-Zeckhauser paper: they are several steps closer to the mainstream. Aldy served as the Special Assistant to the President for Energy and Environment in 2009-2010. Zeckhauser works in in the tradition of tough-minded cooperation pioneered by his mentor, the policy intellectual (and Nobel laureate) Thomas Schelling.

But if we can’t handle a virus, what hope is there of devising effective policies against climate change? That’s just the point: we can handle a virus. It just takes a year, or, probably, two. The problem of arresting global warming is much more difficult, but if you believe the science, there can be no doubt that disastrous events will sooner or later cause public opinion around the world to come around

Wisdom begins with the recognition that there are three policy prongs with which to address the problem of greenhouse gases, not just one. Slowing the effects of carbon dioxide emissions – while continuing to slow emissions themselves – turns on the next election, and the two or three elections after that.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

© 2020 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

web design by PISH P

David Warsh: Why conservative Caldwell denounces 1964's Civil Rights Act

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Among the guests behind him is Martin Luther King Jr.

— Photo by Cecil Stoughton

Presidential campaigns are built on webs of contingency. If Joe Biden’s candidacy had failed at some stage, Amy Kobuchar or Pete Buttigieg might have run the table against Bernie Sanders. Or Sanders might have run the table against one of them. Or Mike Bloomberg might have gained the Democratic Party’s nomination.

But U.S. Rep. James Clyburn’s speech endorsing Joe Biden before the South Carolina primary established a two-person race practically overnight and vaulted Biden into the lead. “I know Joe,” Clyburn said. “We know Joe. Most important, Joe knows us.” To better understand how 11 words could have been so powerful, I turned to The Age of Entitlement: America since the Sixties, by Christopher Caldwell (Simon and Schuster, 2020.)

Caldwell, a contributing editor to the Claremont Review of Books and an occasional opinion columnist for The New York Times, is one of a handful of authors I follow hoping to understand what has happened to the Republican Party. Myriad streams of opinion influence Republican position-taking, of course. I am interested mainly in those that can be described as revisionist history.

They don’t come much more revisionist than Caldwell. Globalization and technology have little do with the polarization of the present day, according to him. The vile mood stems instead from the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

What was intended to be “a transitional measure leading to a stable, racially mixed society,” metastasized into the template of a bill of rights for women, immigrants, LGBTs, the handicapped, the aged, and environmentalists, Caldwell says. Courts and bureaucracies have replaced democracy. The ideology of civil rights, relabeled human rights, hardened into a body of legislation and case law that today amounts to a second constitution, according to Caldwell, at odds with the version of 1788.

Those who lost most from the new rights-based identity politics were white men, he writes, because the new laws helped everybody but them. “They fell asleep thinking of themselves as the people who had built this country, and woke up to find themselves occupying the bottom rung of an official hierarchy of races.”

In this telling, the U.S. Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment, with its guarantees of equal protection and due process under the law, was a bridge too far, passed in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. The Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, would have been enough. The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown vs. Board of Education, in 1954, was a mistake, in that it “put certain public bodies under surveillance for racism.” Rosa Parks was not a weary seamstress looking for a place to sit down on a bus; she was trained agitator, an intellectual leader of the Montgomery, Ala., chapter of the NAACP, a soldier in what Harry Kalven Jr., a long-ago University of Chicago professor of law, described as “an almost military assault on the Constitution.” Robert Bork was “a towering figure in American legal philosophy” for expressing his misgivings about the constitutionality of civil rights legislation. And 1992 presidential candidate Pat Buchanan was a seer, for having run the first campaign against globalization. (For a fuller account of The Age of Entitlement, see Johnathan Rauch’s incisive review.)

Today, Caldwell concludes:

Democrats, loyal to the 1964 constitution, [cannot] acknowledge, (or even see) that they owed their ascendancy to a rollback of the basic constitutional freedoms [of association] Americans cherished most. Republicans, loyal to the-1964 constitution, [cannot] acknowledge (or even see) that the only way back to the free country their ideals was through the repeal of the civil rights laws.

It’s a coherent position, vigorously argued. Its resentment of elites of all sorts, real and imagined, is certainly the tacit position of President Trump. Surely it is a distillation of views opposition to which inspired Rep. Clyburn’s endorsement of Senaor Biden.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

David Warsh: 'Technocrats vs. democrats?'

Flowchart of four phases (enrollment, allocation, intervention, follow-up, and data analysis) of a parallel randomized trial of two groups (in a controlled trial, one of the interventions serves as the control), modified from the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) 2010 Statement.

—From Wikipedia

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Ten years ago, Princeton University economist Angus Deaton used his Keynes Lecture to the British Academy to sound a note of caution about the new New Thing in development economics: the randomized controlled trial (RCT), or field experiment. He recounted the general frustration with the failure of traditional econometric methods to swiftly unlock the secrets of economic development (and with the inability of development agencies to learn more from their own experience). He surveyed the rising enthusiasm for RCTs as an alternative path to reliable knowledge without the traditional fuss.

He argued against the trend. “[E]xperiments have no special ability to produce more credible knowledge than other methods, and… actual experiments are frequently subject to practical problems that undermine any claims to statistical or epistemic superiority.” Citing a maxim of philosopher Nancy Cartwright, Deaton wrote,

Randomization is not a gold standard because “there is no gold standard,” Randomized controlled trials cannot automatically trump other evidence, they do not occupy any special place in some hierarchy of evidence, nor does it make sense to refer to them as “hard” while other methods are “soft”. These rhetorical devices are just that; a metaphor is not an argument.

More positively, Deaton continued,

I shall argue that the analysis of projects needs to be refocused towards the investigation of potentially generalizable mechanisms that explain why and in what contexts projects can be expected to work. The best of the experimental work in development economics already does so, because its practitioners are too talented to be bound by their own methodological prescriptions. Yet there would be much to be said for doing so more openly. I concur with the general message in [Ray] Pawson and [Nick] Tilley…, who argue that thirty years of project evaluation in sociology, education and criminology was largely unsuccessful because it focused on whether projects work instead of on why they work.

Nevertheless, the RCT movement continued to attract adherents, and researchers attracted more and for funding from the World Bank and like-minded foundations with an interest in ameliorating global poverty. Poor Economics A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty (Public Affairs, 2012), by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, both of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, imparted an impetus to the movement. Duflo’s 2017 Ely Lecture to the annual meeting of the American Economic Association, The Economist as Plumber, especially attracted interest. As economists seek to help governments design new policies and regulations, she argued,

[T]hey take on an added responsibility to engage with the details of policy making and, in doing so, to adopt the mindset of a plumber. Plumbers try to predict as well as possible what may work in the real world, mindful that tinkering and adjusting will be necessary since our models gives us very little theoretical guidance on what (and how) details will matter. Economists should seriously engage with plumbing, in the interest of both society and our discipline.

In 2015, awarding the Nobel Prize for economics, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences cited Deaton “for his analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare.” Last month, they cited Banerjee, Duflo, and Michael Kremer, of Harvard University, “for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty.”

Last week Deaton was back, with “Randomization in the tropics revisited: a theme and eleven variations,” a chapter prepared for Randomized Controlled Trials in the Field of Development: a Critical Perspective (Oxford, forthcoming), by Florent Bédécarrats, Isabelle Guérin and François Roubaud, Economic Principals tumbled to Deaton’s essay too late to do much more than read it and recommend it here. Many EP readers will wish to read it for themselves. Deaton is a remarkably clear and forceful writer.

This time the tenor was a little more personal.

Jean Drèze has provided an excellent discussion of the issues of going from evidence for policy. One of his examples is the provision of eggs to schoolchildren in India, a country where many children are inadequately nourished. An RCT could be used to establish that children provided with eggs come to school more often, learn more, and are better nourished. For many donors and RCT advocates, that would be enough to push for a “school eggs” policy. But policy depends on many other things; there is a powerful vegetarian lobby that will oppose it, there is a poultry industry that will lobby, and another group that will claim that their powdered eggs – or even their patented egg substitute – will do better still. Dealing with such questions is not the territory of the experimenters, but of politicians, and of the many others with expertise in policy administration. Social plumbing should be left to social plumbers, not experimental economists who have no special knowledge, and no legitimacy at all.

The argument – does it load the dice to call it technocrats vs. democrats? – promises to be long running, with attention soon to shift to Silicon Valley know-it-alls and the Gates Foundation. Banerjee and Duflo’s new book, Good Economics for Hard Times (Public Affairs) appears November 12. The next chapter will air Dec. 8, when this year’s laureates are scheduled to give their lectures in Stockholm – live-streamed, for those who care to watch.

. xxx

New on the Economic Principals bookshelf:

The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution, by Gregory Zuckerman (Penguin)

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

]

Da

David Warsh: The young and the restless in presidential politics

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It has long seemed to me that the United States began to lose its way in 1992, when Bill Clinton defeated George. H. W. Bush for the presidency. The Berlin Wall had fallen. The Soviet Union had disbanded. The Cold War had ended. Bush was highly popular in the wake of the First Gulf War.

Leading Democrats – such as Gov. Mario Cuomo, Jesse Jackson and Sen. Al Gore — declined to run. (Gore’s son had been gravely injured in an auto accident.) Instead, Gov. Bill Clinton, former Gov. Jerry Brown, Senators Paul Tsongas, Bob Kerrey and Tom Harkin all joined the chase.

Bush reappointed Alan Greenspan as chairman of the Fed, but later charged that Greenspan reneged on a promise to ease monetary policy slightly, to compensate for the tax increase that Bush had requested to pay for the war and the mild recession (July 1990-March ’91) that had resulted. The recovery in the year before the election was unusually tepid.

Populist commentator Pat Buchanan ran against Bush from the right in Republican primaries. Though he won no states, he polled more votes than expected, especially in New Hampshire. As Buchanan faded, an emboldened H. Ross Perot entered the campaign as an independent candidate, exited, and re-entered. He won 19 percent of the popular vote in the end but failed to gain a single electoral vote.

Clinton won the election. After 12 years as vice president and president, Bush was all-too-familiar; Clinton was fresh. Bush had been the youngest Navy pilot in World War II. Clinton was a Baby Boomer who skipped Vietnam. Bush lacked energy; Clinton was a dynamo.

America enjoyed a few years of exhilaration in the Nineties: the introduction of the Internet; a dot.com mania; and, thanks to eight years of brisk growth, a balanced federal budget, after 20 years of surging deficits,. Looking back, though, Clinton was ill prepared by his years as Arkansas governor to make foreign policy. Two years as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford had made him overconfident as well.

Unilateral humanitarian interventions followed in the Balkan civil wars that flared after the Soviet Union collapsed. NATO expansions were undertaken that the Bush administration, expecting a second term, had promised would not occur. Russia protested, but was powerless to prevent any of it. Vladimir Putin replaced Boris Yeltsin and grew increasingly resentful.

Without the discipline imposed by of the Cold War, domestic politics turned rambunctious as well. Clinton empowered his wife to seek to overhaul U.S. health insurance. Congressman Newt Gingrich replied with his “Contract with America,” gained 54 House seats and 9 Senate seats in the 1994 mid-term elections. Republican enmity toward Clinton, which had begun to overspill the bounds of decency soon after the inauguration, reached flood levels with the impeachment and failed conviction proceedings of Clinton’s second term.

The next two presidencies, 16 years, amounted to more of the same. NATO expansion continued, reaching the borders of Russia. Relations with China remained amicable throughout. George W. Bush started wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Barack Obama pursued regime change in Libya (successfully) and Syria (unsuccessfully). The third presidential go-round, which started out in 2015 as a presumed Bush-Clinton rematch (Jeb Bush vs. Hillary Clinton) is what eventually got us to Trump.

Now Americans may be about to do it again – to prefer youth and personal ambition to consensus. The situation today is a little like 1992 in reverse. An over-abundance of Democratic Party candidates are eager to take on Donald Trump (or, in the event that he prefers not to run, Vice President Mike Pence). California Sen.

Kamala Harris damaged former Vice President Joe Biden in the debate last week. She projected youth and vigor. Biden was cautious; he had to contend with his record over 44 years of swiftly changing national politics. That Harris used the murky issue of federal court-ordered busing to attack Biden struck me as especially low. Nevertheless, Harris emerged as a candidate capable of taking on Trump. Her next challenge will be to finesse the health-care issue that handcuffed her in the debate.

She is also the candidate to watch out for, as Clinton was the candidate to watch out for in 1992. Clinton’s character didn’t come into focus until 1995, when First in His Class, David Maraniss’s brilliant biography, appeared. Harris will presumably receive a series of earlier screenings. Her appeal to her base, women and African Americans, is obvious. It remains to be seen whether she can persuade swing constituencies near the center of American political life,

Leaping far ahead, my guess is that only a better-than-expected showing by Biden or South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg in the California primary on Super Tuesday, March 3 (if they survive that long), will force Harris to wait. Bill Clinton would have been a much better president if he had first been elected in 1996. Mitt Romney might have defeated Hillary Clinton if he had waited until 2016.

But the young and/or the restless have dominated the top of the food chain for the last 28 years. True, it was John F. Kennedy who first jumped the queue, an element of collective memory that Clinton employed to enhance his license. With the exception of Barack Obama, they haven’t been good for the country.

David Warsh, an economic historian and long-time columnist on business, politics and media, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Trump looks like a one-term president at this point

For a column that likes to look a little forward, the Trump presidency is a considerable roadblock. It won’t be possible to write with confidence about the American story until his administration is succeeded by the next. For that matter, Donald Trump himself can’t think very far ahead in these circumstances, and, while he improvises well, he is clearly not a man accustomed to planning well into the future.

So the intriguing question for the moment remains, what happens if the then 74-year-old Trump declares victory and doesn’t run again? What if he waits to announce, perhaps at the last possible moment, in July 2020, “I’ve accomplished what I was elected to do” and moves on to build his library? Sixty-year-old Vice President Mike Pence presumably would be more than ready to run.

It’s in this context that the latest developments should be understood – both his impending nomination of a second member to the Supreme Court and the planned trip to meet Vladimir Putin in Helsinki. Both seem to me to bolster the likelihood that, when the time comes, Trump will prefer to be a one-term president rather than take his chances trying to win a second term.

There’s no arguing with the fact that Trump has a chance to influence the Supreme Court for another 20 to 25 years. But the course that any particular justice’s influence might take on a nine-person court is very hard to predict. The Senate is narrowly divided and that will constrain the choice. The president met June 28 at the White House with Senate Judiciary Chairman Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) and the five senators whose votes will likely determine the fate of any nomination: Republicans Susan Collins, of Maine, and Lisa Murkowski, of Alaska; and Democrats Joe Donnelley, of Indiana, Heidi Heitkamp, of North Dakota, and Joe Manchin, of West Virginia,

As for the Helsinki meeting, Trump will talk to Putin about Syria and Iran, in hopes of finding some sort of mutual accommodation that might ratchet down the violence there. Some lifting of sanctions on trade will probably be part of the discussion. Putin may put back on the table the proposal for an across-the-board renormalization of relations that he privately transmitted through diplomatic channels last year. Trump may choose to talk instead of the joint measures against election-tampering that he broached, then backed away from, a year ago. He promised to “talk about everything” when the two meet. “Perhaps the world can de-escalate,” the president said. “We might be talking about some things President Obama lost.”

Obama’s foreign policy is not the issue. Even without Trump, American voters are probably returning to the realist, balance-of-power view of relations with Russia that dominated U.S. politics for the 45 years of the Cold War. The conviction that the United States is duty-bound to spread its values around the world, associated with Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush and the candidacy of Hillary Clinton, has been losing force everywhere but the Atlantic Council.

In this view, foreign policy towards Russia is a sideshow that will largely take care of itself. The real story is Trump himself. What got him elected was his tough talk on immigration and trade. What sustains his popularity, as best I can tell, is the very considerable set of skills he acquired as a reality-TV performer on The Apprentice and Celebrity Apprentice. In this respect, Trump is like Ronald Reagan.

In every other respect, he is different. Reagan stressed alliances; Trump breaks them apart. Reagan was cheerful and friendly; Trump is a bully and a boor. Reagan made some bad appointments; Trump appointees have committed wholesale administrative vandalism. Reagan had confidence in the verdict of history; Trump makes war on it. The Iran-Contra hearings failed to seriously touch Reagan; the Mueller probe remains a dagger at the heart of Trump’s current term.

So see what happens in the November mid-term elections. Pay careful attention to polls next year. Much depends on who wins the Democratic primaries. Then there will be the 2020 congressional elections to consider – what if the Dems take back both houses? Where would be the fun in that? And, of course, keep an eye on the bond market, that harbinger of recession. It is always possible that Trump will run the table and, like Clinton, Bush, and Obama, settle into a second term more comfortable than the one before. I put the chances at one in three.

David Warsh, a Somerville, Mass.-based longtime columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com

Search for: