David Warsh: 'Suzerainties in economics are personal'

The Great Dome at the Massachusetss Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Mass.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

When I was a young journalist, just starting out, the economist whose writings introduced me to the field was Gunnar Myrdal. He hadn’t yet been recognized with a Nobel Prize, as a socialist harnessed to an individualist, Friedrich Hayek. That happened in in 1974. But he had written An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944) , about the policy of segregation that had been restored de jure after the U.S. Civil War. A subsequent project, Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations (1968), longer in preparation, was in the news.

Myrdal’s pessimistic assessment of the prospects for economic growth in India, Vietnam, and China began to fade soon after it appeared. The between-the-wars era of economics in which he was prominent already had been superseded by a new era, dominated by Paul Samuelson, whose introductory college textbook Economics (1948), supplemented by the highly technical Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947), quickly replaced overnight Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics, whose first edition had appeared in 1890.

Basic textbooks dominate their fields by dint of the housekeeping that they establish. Samuelson has ruled economics ever since through the language he promulgated; mathematical reasoning was widely adopted within a few years by newcomers to the profession. Ruling textbooks are sovereign. Since the discovery and identification of the market system two hundred and fifty years ago, there have been only five such sovereign versions: Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Alfred Marshall, and Samuelson (brought up to knowledge’s frontiers thirty years ago by Andreu Mas-Colell).

Sovereignty is binary; it either exists or doesn’t. A suzerainty, on the other hand, though part of the main, sets its own agenda. John Fairbank taught that Tibet was a suzerainty of China. (This Old French word signifies a medieval concept, adopted here to describe modern sciences, as in Dani Rodrik’s One Economics, Many Recipes (2007).

Suzerainties are personal. They rule through personal example. Replacing Myrdal as suzerain in my mind, in 1974, practically overnight, was Robert Solow. Eight years his junior, Solow was Samuelson’s research partner at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for the next thirty years. Samuelson retired in 1982, died in 2009. Solow soldiered on.

Solow turned 99 last week, hard of hearing but sharp as ever otherwise (listen to this revealing interview if you doubt it.) By now his suzerainty has passed to Professor Sir Angus Deaton, 78, of Princeton University.

What is required to become a suzerain? Presidency of the American Economic Association and a Nobel Prize are probably the basic requirements: recognition by two distinct communities, one for good citizenship within the profession, the other for scientific achievement beyond it, to the benefit to all humanity.

In Deaton’s case, as in Myrdal’s, it helps to have displayed a touch of Alexis de Tocqueville, whose two-volume classic of 1835 and 1840, Democracy in America, set the standard for critical criticism by a visitor from another culture, and, in the process, founded the systematic study today we call political science. Deaton grew up in Scotland, earned his degrees at Cambridge University, and was professor of economics at the University of Bristol for eight years, before moving to Princeton. in 1983. For the first twenty years he taught and worked in relative obscurity on intricate econometric issues. In 1997, he began writing regular letters for the Royal Economic Society Newsletter, reflecting on what he had learned recently about American life, “sometimes in awe, and sometimes in shock”.

In 2015, the year Deaton was recognized by the Nobel Foundation for “his analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare,” he published The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Five years later, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism appeared, by Deaton and Anne Case, his fellow Princeton professor and economist wife, just as the Covid epidemic began. It became a national best-seller, focusing attention on the fact that life expectancy in the United States had recently fallen for three years in a row – “a reversal not seen since 1918 or in any other wealthy nation in modern times.”

Hundreds of thousands of Americans had already died in the opioid crisis, they wrote, tying those losses, and more to come, to “the weakening position of labor, the growing power of corporations, and, above all, to a rapacious health-care sector that redistributes working-class wages into the pockets of the wealthy.”

Now Deaton has written a coda to all that. Economics in America: An Immigrant Economist Explores the Land of Inequality (Princeton 2023) will appear in October, offering a backstage tour during the year that Deaton has been near or at the pinnacle of it. I spent most of Friday and Saturday morning reading it, more than I ordinarily allot to a book, and found myself absorbed in its stories about particular people and controversies, on the one hand, and, on the other, increasingly apprehensive about finding something pointed about it to say.

Then it occurred to me. I have long been a fan of Ernst Berndt’s introductory text, The Practice of Econometrics: Classic and Contemporary (Addison-Wesley, 1991), mainly because it scattered one- or two-page profiles of leading econometricians throughout pages of explication of their ideas and tools. Deaton’s new book is far better than that, because no equations are to be found in the book, and part of some of those letters to British economists have been carefully worked in.

The argument about David Card and the late Alan Krueger’s celebrated paper pater about a natural experiment with the minimum wage along two sides of the Delaware River, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, is carefully rehashed (both were Deaton’s students). The goings-on at Social Security Day at the Summer Institute of the National Bureau of Economic Research is described. The “big push” debate in development economics among William Easterly, Jeffrey Sachs, Treasury Secretary Paul H O’Neill, and Joseph Stiglitz get a good going-over. Econometrician Steve Pischke’s three disparaging reviews of Freakonomics are mentioned. Rober Barro and Edward Prescott are raked over with dry Scottish wit; Edmond Malinvaud, Esra Bennathan, Hans Binswanger-Mkhizer, and John DiNardo are celebrated. The starting salaried of the most sought-after among each year’s newly-minted economics PhDs are discussed:

My taste is for theory because developments in theory are where news is apt to be found. That’s why I liked Great Escape and Deaths of Despair so much. Economics in America is undoubtedly the best book about applied economics I’ve ever read, its breadth and depth. But it is a book about applied economics – the meat and potatoes topics that I have tended to avoid over the years. What I craved when I finished is a book about the one-time land of equality that is Britain today.

Other suzerainties exist in economics. The same and/or credentials apply: presidency of the AEA and realistic hopes of a possible Nobel Prize. They tend to be associated with particular universities: Robert Wilson, Guido Imbens, Susan Athey, Paul Milgrom and Alvin Roth at Stanford; George Akerlof (emeritus), David Card and Daniel McFadden at Berkeley; Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz at Harvard; William Nordhaus and Robert Shiller at Yale; James Heckman and Richard Thaler at Chicago; Daron Acemoglu and Peter Diamond at MIT; Sir Angus Deaton, Christopher Sims, and Avinash Dixit at Princeton.

Alas, the reigning head of the suzerainty in which I am most interested, macroeconomist Robert Lucas, died earlier this year, and won’t soon be replaced. He succeeded Sherwin Rosen, his best friend in the business, in the AEA presidency in 2001. Rosen died the same year, a decade or two short of what might have been his own trip to Stockholm.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Searching under streetlights for economic answers

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As a young magazine writer, I was a quick enough study to recognize that, in the discussion of inflation, the bourgeoning enthusiasm for monetary analysis had loaded the dice in favor of the quantity theory of money. New World treasure, paper money, central banking: it was as if monetary policy was a force independent of whatever might be happening in the economy itself. It reminded me a famous New Yorker cartoon, a patient talking to his psychoanalyst: “Gold was at $34 when my father died… it was $44 when I married my wife… now it’s $28, but I have trouble seeing.”

I wanted to suggest a variable that might represent the perspective of real analysis, though I did not yet know the term: the conviction, as I learned Joseph Schumpeter had described it, that “all the essential phenomena of economic life are capable of being described in terms of goods and services, of decisions about them, and relations between them,” and that money entered the picture as just another a technological device. Thinking about all else besides monetary innovation that was new in the world since the 15th Century, I came up with a catch-word to describe what had changed. The Idea of Economic Complexity (Viking) appeared in 1984.

It certainly wasn’t theory: more in the nature of criticism, a slogan with so little connection to the discourse of economics since Adam Smith that it didn’t bother specifying complexity of what. But the word had an undeniable appeal. “Complexity,” I wrote, “is an idea on the tip of the modern tongue.”

Sure enough: Chaos: Making a New Science, by James Gleick, appeared in 1987; Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Chaos and Order, by M. Mitchel Waldrop; and Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos, by Roger Lewin, followed in 1992; and in the next decade, a whole shelf of books appeared, of which The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Remaking of Economics, by Eric Beinhocker, in 2006, was probably the most interesting.

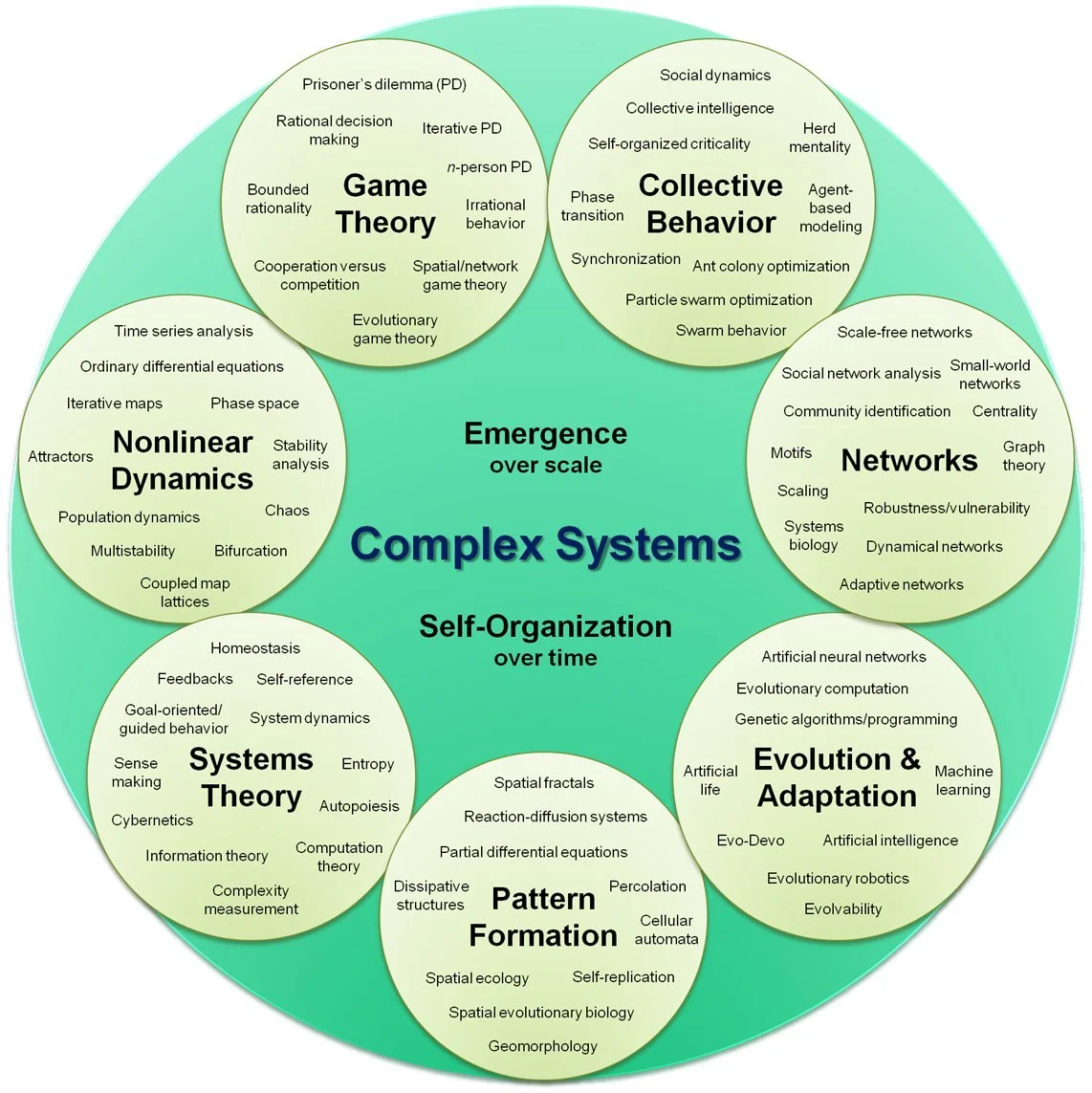

Organizational map of complex systems broken into seven sub-groups.

— Hiroki Sayama, D.Sc

But the question remained: complexity of what? The long quote-box on the back of the book jacket had put it this way:

To be complex is to consist of two or more separable, analyzable parts, so the degree of complexity of an economy consists of the number of different kinds of jobs in the system and the manner of their organization and interdependence in firms, industries, and so forth. Economic complexity is reflected, crudely, in the Yellow Pages, by occupation dictionaries, and by standard industrial classification (SIC) codes. It can be measured by sophisticate modern techniques, such a graph theory or automata theory. The whys and wherefores of our subject are not our subject here, however. It is with the idea itself that we are concerned. A high degree of complexity is what hits you in the face in a walk across New York City; it is what is missing in Dubuque, Iowa. A higher degree of specialization and interdependence – not merely more money or greater wealth – is what make the world of 1984 so different from the world of 1939.

Fair enough, for purposes of journalism. There was however something missing in my discussion: to wit, any real knowledge of structure of technical economic thought. I had come across the economist Allyn Young (1876-1929) in my reading, a little-remembered contemporary of Irving Fisher, Wesley Clair Mitchel and Thorstein Veblen, Schumpeter, and John Maynard Keynes. I classified him, with Schumpeter, as a “supply-sider,” in keeping with the controversies of the early ‘80’s, “locating in the businessman’s entrepreneurial search for markets the most profound impulse toward economic growth.” I added only that “We are coming at it from a slightly different direction is this book.”

It wasn’t until I re-read “Increasing Returns and Economic Progress” (for those who have access to JSTOR), in the Economic Journal of December 1928, that it dawned on me that it was complexity of the division of labor that I had been thinking about. A particular passage towards the end of Young’s paper brought it home.

The successors of the early printers, it has often been observed, are not only the printers of today, with their own specialized establishments, but also the producers of wood pulp, of various kinds of paper, of inks and their different ingredients, of type-metal and of type, the group of industries concerned with the technical parts of the producing of illustrations, and the manufacturers of specialized tools and machines for use in printing and in these various auxiliary industries. The list could be extended, both by enumerating other industries which are directly ancillary to the present printing trades and by going back to industries which, while supplying the industries which supply the printing trades, also supply other industries, concerned with preliminary stages in the making of final products other than printed books and newspapers. I do not think that the printing trades are an exceptional instance, but I shall not give other examples, for I do not want this paper to be too much like a primer of descriptive economics or an index to the reports of a census of production. It is sufficiently obvious, anyhow, that over a large part of the field of industry an increasingly intricate nexus of specialized undertakings has inserted itself between the producer of raw materials and the consumer of the final product.

Young, a University of Wisconsin PhD, had taught both Edward Chamberlin and Frank Knight as a Harvard professor, before accepting an offer from the London School of Economics to chair its department, at a time when LSE was looking to further distinguish itself. It was as president of Section F of the British Association for the Advancement of Science that he delivered his paper on increasing returns. Then, on the verge of returning to Harvard, he died at in an influenza epidemic. He was 52.

By the time that I re-read Young’s paper, I had met Paul Romer, a young mathematical economist then at the University of California Berkley, who had been working for years on more or less exactly the same questions that Allyn Young had raised in literary fashion fifty years before. Romer introduced me to the distinction economists made between “endogenous” and “exogenous” factors.

Endogenous were developments within the economic system; exogenous were those apparently outside, to be “bracketed” or put aside as matters the existing system hadn’t yet found ways to satisfactorily explain. Only a few years earlier, Robert Solow, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had been recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for, among other things, his finding that as much of 80 percent of economic growth in a certain period couldn’t be explained by additional increments of labor and capital. Whatever it was, it was to be expressed as a “Residual,” exogenous to the system of supply and demand.

First in “Growth Based on Increasing Return Due to Specialization,” in 1987, then in “Endogenous Technical Change,” in 1990, Romer solved the problem, employing new mathematics he had acquired to describe it. The magic of the Residual, it turned out, was human knowledge, a non-rival good in that, unlike land, labor, or capital, it could be possessed by any number of persons at the same time. I wrote a book about what had happened; Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton) appeared in 2006. In 2018, Romer, by then at New York University, and William Nordhaus, of Yale University, shared a Nobel Memorial Prize for their work on the interplay of technological development and climate change.

I had been hit by the meatball. I understood why Early Hamilton and John Neff had so little to say to each other, why Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson didn’t agree: they were men searching under streetlights for answers – different streetlights, separated by areas of darkness that had yet to be illuminated. I understood that economists could be trusted to continue to develop their field,

But there were still plenty of questions to be answered, including the one that had bothered me since the beginning. Why do we call rising prices “inflation?”

xxx

One of the joys of writing about the news is that you ordinarily never know where you’re going from one week to the next – reading as well, I expect. Yet from small beginnings last autumn, I have launched a mini-series about some things I have learned since publishing The Idea of Economic Complexity in 1984. Had I known at the beginning what to expect, I would have announced a series, Complexity Revisited. I do so now.

This week is the fourth installment, counting the first piece – about the 700-year wage and price index of Sir Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins – that triggered the rest. There will be four more, eight in all. Each piece subsequent to the first is connected to something I discovered later, in the witings of Joseph Schumpeter, Charles Kindleberger, Allyn Young, Steven Shapin and Simon Schafer, Nicholas Kaldor, Hendrik Houthakker, and Thomas Stapleford.

What’s the point? It all has to do with the nature of money – how we control it, how it is accumulated, saved and disbursed. Banking is already thoroughly digitized; the digitalization of money itself looms in the future. It makes sense to go back to first principles. These have to do with central banking, it turns out, perhaps the least understood of major modern institutions of governance.

The need here to think matters through, at least a little, arose in connection with other projects underway, large and small. I don’t apologize for having undertaken the series. I’ve done it twice before over the years, each time with good results. But there is something about the weekly column that wants to stay close to the news, especially in these turbulent times. I can confidently promise not to do it again. Back to the news next month.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

— Photo by Acabashi

David Warsh: An old man against the world; don't eat WSJ baloney on Texas crisis

Rupert Murdoch

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper chose a good week in which to write about a leading skeptic of climate change. “For all the anxiety about fake news on social media,” Kuper wrote last weekend, “disinformation on climate seems to stem disproportionately from one old man using old media.”

He meant Rupert Murdoch, 89, whose company, News Corp., owns The Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, The Times of London, and half the newspaper industry in Australia. Honored with a lifetime achievement award in January by the Australia Day Foundation, a British organization, Murdoch posted a video:

“For those of us in media, there’s a real challenge to confront: a wave of censorship that seeks to silence conversation, to stifle debate, to ultimately stop individuals and societies from realizing their potential. This rigidly enforced conformity, aided and abetted by so-called social media, is a straitjacket on sensibility. Too many people have fought too hard in too many places for freedom of speech to be suppressed by this awful ‘woke’ orthodoxy.”

There is some truth in that, of course – but not enough to justify the misleading baloney on the cause of crisis in Texas which the editorial pages of the WSJ published last week.

Murdoch is a canny newspaperman, and since acquiring The WSJ, in 2007, he has the good sense not to tamper overmuch with its long tradition of sophistication and sobriety in its news pages. He even replaced the man he had put in charge of the paper, Gerard Baker, after staffers complaints that Baker’s thumb was found too frequently on the scale of its coverage of Donald Trump.

Then again, neither has he tinkered with the more controversial traditions of the newspaper’s editorial opinion pages, to which Baker has since been reassigned as a columnist. The story has often been told about how managing editor Barney Kilgore transformed a small-circulation financial newspaper competing mainly with The Journal of Commerce in the years before World War II into a nationwide competitor to The New York Times, and worth $5 billion to Murdoch. A major contributor to it was Vermont Royster, editor of the editorial pages in 1958–71; and an occasional columnist for the paper for another two decades years after that. He was succeeded by Robert Bartley. Royster died in 1996.

In 1982, Royster characterized the beginnings of the change this way: “When I was writing editorials, I was always a little bit conscious of the possibility that I might be wrong. Bartley doesn’t tend to do that so much. He is not conscious of the possibility that he is wrong.”

Royster hadn’t seen anything yet. With every passing year, Bartley became firmer in his opinions. In the 1990s, his editorial pages played a leading role in bringing about the impeachment of President Clinton. Bartley died in 2002, and was succeeded by Paul Gigot, who has presided over a continuation of the tradition of hyper-confidence. The editorial page enthusiastically supported Donald Trump until the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol.

Last week the WSJ published four editorials on the situation in Texas.

Tuesday, A Deep Green Freeze: “[A[n Arctic blast has frozen wind turbines. Herein is the paradox of the left’s climate agenda: the less we use fossil fuels, the more we need them.”

Wednesday, Political Making of a Power Outage: “The Problem is Texas’s overreliance on wind power that has left the grid more vulnerable to bad weather than before.”

Thursday, Texas Spins in the Wind: “While millions of Texans remain without power for the third day, the wind industry and its advocates are spinning a fable that gas, coal, and nuclear plants – not their frozen turbines – are to blame.”

Saturday, Biden Rescues Texas with… Oil: “The Left’s denialism that the failure of wind power played a starring role in Texas catastrophic power outage has been remarkable”

Then on Saturday, the news pages weighed in, flatly contradicting the on-going editorial-page version of events with a thoroughly reported account of its own, The Texas Freeze: Why State’s Power Grid Failed: “The core problem: Power providers can reap rewards by supplying electricity to Texas customers, but they aren’t required to do it and face no penalties for failing to deliver during a lengthy emergency.

“That led to the fiasco that led millions of people in the nation’s second-most populous state without power for days. A severe storm paralyzed almost every energy source, from power plants to wind turbines, because their owners hadn’t made the investments needed to produce electricity in subfreezing temperatures.”

All three major American newspapers are facing major decisions in the coming year: Amazon’s Jeff Bezos must replace retiring executive editor Martin Baron at The Washington Post; New York Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger presumably will name a successor to executive editor Dean Baquet, who will turn 65 in September (66 is retirement age there); and Murdoch will presumably replace Gigot, who will be 66 in May.

The WSJ editorial page could play an important role in American politics going forward by sobering up. But only if Murdoch – or, more likely, his eldest son, Lachlan, who turns 50 this autumn – selects an editor who writes sensibly, conservatively, about dealing with climate change.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Editor’s note: Both Mr. Warsh and New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, are Wall Street Journal alumni.

David Warsh: Climate change and economic modeling

Flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Super Storm Sandy on Oct. 29, 2012.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The unexpected pairing of environmental and growth economics by the Nobel committee this year contains many surprises. William Nordhaus and Paul Romer are surprisingly similar in their origins. Each is a member of an entrepreneurial family in the American West. Nordhaus is the youngest of four brothers; his father, Robert, was a ski developer and sheep rancher in New Mexico. Romer is the second of seven children; his father, Roy, is a John Deere dealer and former governor of Colorado. Each graduated from an elite high school in the East (Andover and Exeter) before attending college (Yale and the University of Chicago). Both began their graduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Yet the two economists’ careers could scarcely have been more different. Nordhaus, 77, is a master of social engagement and consensus. Romer, who turns 63 on Nov. 7, is a lifelong innovator and frequent disruptor of the intellectual neighborhoods in which he has found himself. Nordhaus is the world’s foremost authority on the economics of climate change. Romer is a major figure in the history of economics, who after 20 years left economics to become a public intellectual. The Swedes, having put the two together, made it worthwhile to tell them apart.

The most striking thing about Nordhaus is the steadily expanding cone of his influence over 50 years. He immediately returned to Yale after completing his PhD in just four years at MIT and has never left, except for occasional sojourns, the first of them the most significant: 1974-75 at the International Institute for Applied Systems in Vienna, the cradle of climate modeling. He spent two years as a member of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, 1977-79, served as provost at Yale, 1986-88, and as vice president for finance and administration, there in 1992-93.

As a member of the National Academy of Sciences, Nordhaus served on numerous interdisciplinary committees, including: the Committee on Nuclear and Alternative Energy Systems, the Panel on Policy Implications of Greenhouse Warming, the Committee on National Statistics, the Committee on Data and Research on Illegal Drugs, and the Committee on the Implications for Science and Society of Abrupt Climate Change. In 2014, Nordhaus served as president of the American Economic Association.

He was co-author, with Paul Samuelson, of later editions of the classic textbook Economics, whose 19th and final edition was published in 2009. His most recent books on climate change are A Question of Balance: Weighing the Options on Global Warming Policy (2008) and The Climate Casino: Risk, Uncertainty, and Economics for a Warming World (2013).To call him well-connected is an understatement.

Significantly, Nordhaus began his career working on the same problem that Romer later solved: how to bring knowledge creation within the compass of economic theory, instead of simply assuming its steady increase, as is conventional in macroeconomics modelling even today. “An Economic Theory of Technological Change” appeared in the American Economic Review in 1969; Invention, Growth, and Welfare: A Theoretical Treatment of Technological Change later the same year ($93.34 for an out-of-print copy) but for reasons that have never been entirely clear, Nordhaus’s thesis failed to attract the attention that would have allowed him to pursue the question. By 1972, he was working, with fellow Yale professor (and future Nobel laureate) James Tobin, on incorporating natural resources and household accounts in national income accounting – soon dubbed “green accounting.” In Is Growth Obsolete?, in 1973, the authors concluded,

At present there is no reason to arrest general economic growth to conserve natural resources, although there is good reason to provide proper economic incentives to conserve resources which currently cost their users less than true social cost.

In Vienna, Nordhaus became interested in the problem of global warming. By 1977, in“Economic Growth and Climate: The Carbon Dioxide Problem,” he argued that

In contemplating the future course of economic growth in the West, scientists are divided between one group crying “wolf” and another which denies that species’ existence. One persistent concern has been that man’s economic activities would reach a scale where the global climate would be significantly affected. Unlike many of the wolf cries, this one, in my opinion, should be taken very seriously.

He has been working on it ever since, developing economic approaches to global warming, including the construction of integrated economic and scientific models to determine the efficient path for coping with climate change. Perhaps it was all but fated, given Nordhaus’s family’s background. In any event, it was this work for which the Nobel Foundation last month cited Nordhaus.

Along the way, he fought off a cancer that could have killed him, worked well with his MIT classmate Martin Weitzman, another authority on climate change, with a different approach; and provided rhetorical support for Romer’s theorizing about the import of new technologies – in particular, Nordhaus’s 1996 study of the economic history of the cost of an evening of indoor lighting since Babylonian times. Nordhaus “returned to Mesopotamian economics,” his biography notes, with a study published on the eve of the invasion of Iraq in which he projected the cost of the war as high as $2 trillion. It was subsequently estimated to have been $3 trillion or more.

A long-term collaboration with Stanford professor John Weyant and his Energy Modeling Forum’s summer Snowmass, Colorado, workshops, helped bring major energy companies into the climate change tent. But corporate participation didn’t prevent Nordhaus, in the final pages of Climate Casino, from comparing ExxonMobil to cigarette manufacturers as having been a “merchant of doubt.” But that has protected him from biting criticism from those who believe that his cautious approach to measurement issues “enabled climate change denial and delay.” For all his mastery of consensus-building, Nordhaus’s central policy recommendation – a global carbon tax – still has a long way to go.

David Warsh, a longtime columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first appeared.

David Warsh: Disillusionment in America and the former Soviet Union

The economics and politics of disillusionment in two nations

Elaine Scarry, an essayist and literature professor, long ago suggested that, in counterpart to the ingenious system of government framed by the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the United States also possessed a material constitution, consisting of the technological systems of the nation and no less remarkable than the political structure for being evolved in practice rather than written down.

Riffing on Scarry’s conception, historian of technology Thomas Hughes noted the tendency to take the latter for granted. The intellectual historian Perry Miller had already observed, in The American Scholar, how casually Americans “flung themselves into the technological torrent, how they shouted with glee in the midst of the cataract, and cried to each other as they went headlong down the chute, that here was their destiny….”

Now, Hughes wrote, with technological momentum accelerating, Americans needed to learn to see themselves as a nation of system builders as well as practitioners of their subtle arrangements of political democracy and free enterprise. American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm (Viking, 1990), Hughes’s classic study of the engineering of the key inventions of the century after 1870 – incandescent light, the telephone, the radio, the airplane, the automobile, electric power – was motivated by a concern for the overlooked burdens that technological enthusiasm frequently imposed. Forty years after the development of modern financial markets for corporate control, containerization, microprocessors, personal computers and the Internet, Hughes’s attentiveness to the sudden eruption of a culture of critique, seems especially prescient: “the organic instead of the mechanical; small and beautiful technology, not centralized systems; spontaneity instead of order; and compassion, not efficiency.”

For the last six months, I have been dipping into the burgeoning literature of disillusionment, trying to understand the Trump election: Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, by Matthew Desmond; Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, by J. D Vance; Janesville: An American Story, by Amy Goldstein; Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, by Arlie Russell Hochschild, and Doctored: The Disillusionment of an American Physician, by Sandeep Jauhar. The book I read all the way through was Glass House: The 1% Economy and the Shattering of an American Town (St. Martin’s, 2017), by Brian Alexander.

Glass House is about Lancaster, Ohio, and the Anchor Hocking Glass Co., upon which the city’s fortunes were built – and then eventually dissipated by rich New Yorkers – over the course of the 20th Century. At a little more than 300 pages, you might think that Glass House is more than you want to know about a little city on the Hocking River, southwest of Columbus, in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains. But Alexander grew up in Lancaster in the 1970s, has stayed in touch (he lives in California now) and, as a highly capable magazine writer, he moves the story along with the force of a novel, interweaving the saga of the business itself with the lives of four friends.

It helps that his tale has plenty of colorful signposts along the way: the Ku Klux Klan in Lancaster in the 1920s; Malcolm Forbes in the early 1940s (his father bought him a newspaper there as a Princeton graduation present); Carl Icahn, (a key Donald Trump adviser today) who in 1983 put Anchor in play; Newell Corp., the vagabond manufacturing firm that in the 1980s rolled up Anchor into a giant conglomerate on the strength of a loan from an Arizona savings andloan association; Cerberus, the private-equity firm organized by Stephen Feinberg (another close Trump adviser today) that bankrupted Anchor; Sam Solomon, the African-American scion of North Carolina farmhands, who, as newly appointed CEO, seeks to save Anchor, now branded as EveryWare Global (Anchor survives, barely, Solomon is fired but becomes the hero of the book).

The leitmotif: at each step along the way, Alexander describes the succession of new drug products that began to plague Lancaster, starting in the 1970s: marijuana, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, Percocet, OxyContin, and Xanax. The greatest charm of Glass House is that its trajectory since the 1980s resembles that of almost any other Middle American manufacturing city you can think of.

Between times, I have been reading Secondhand Time: The Last Days of the Soviets, An Oral History (Random House, 2016), by Svetlana Alexievich, the 69-year-old Belorussian author who was recognized with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015. The book is not easy reading. Like four other “documentary novels” that Alexievich has written over 30 years, chronicling the lives of ordinary citizens of the former Soviet Union since World War II, it consists of a series of collages composed of interviews (“snatches of street noise and kitchen conversations”) with hundreds of characters, some of whom appear and reappear as in any good Russian novel.

The differences between Secondhand Time and Glass House are instructive, the differences between literature and journalism. Secondhand Times begins with a timeline, six pages briefly describing events from the death of Josef Stalin, in 1953 to the Maidan protests, in Kiev, in 2014. Then for 350 pages, consciousness swirls. Alexievich writes:

“The Soviet civilization…. I’m rushing to make impression of its traces, its familiar faces. …The myriad sundry details of a vanished way of life. It’s the only way to chase the catastrophe into the contours of the ordinary and try to tell a story.’’

The triumph of Secondhand Time is to make more understandable how many present-day Russians and others living in former Soviet jurisdictions can feel affection for a system that produced so much misery and permitted so little of the freedom that the Westerners take for granted. Consider the top-down coup that was the Bolshevik Revolution, the Russian Civil War, the murderous collectivization of agriculture, famine, the purges, the Gulag and then the gradual discovery of the awful history that had been hidden.

“Despite the poverty, life was freer” in some respects under communism, Alexievich told Guy Chazan of the Financial Times over dinner last month in Berlin. “Friends would gather at each other’s houses, play the guitar, sing, talk, read poetry.” When democracy came, she said, they expected that everyone would read Solzhenitsyn. Sure enough, with glasnost, Solzhenitsyn’s works were all published in the former Soviet Union, but no one any longer had time to read them. “Everyone just ran past them and headed for twenty different kinds of biscuits and ten varieties of sausage.” The book is about disillusionment plus – how great was the loss of the Great Idea.

I can’t read Alexievich, or any other source on Russian history, without experiencing an overwhelming sense of gratitude for having been born a citizen of the United States. But, as I read Johnson’s Russia List, the indispensable almost-daily chronicle of what the Russians are saying about themselves, it is clear that Russians are gradually coming to grips with their history (Alexievich being a prime example).

There’s no doubt that the government of Russia unwisely sought to underhandedly tamper with the machinery of American democracy in the 2016 election. They didn’t succeed. The Constitution of the United States, both the familiar version enshrined in law and the less-familiar material version, assure that America, for all its sorrows, continues to insure domestic tranquility – more reliably, perhaps, than you think.

David Warsh, a veteran economic historian and columnist on financial, political and historical affairs, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this first ran.

David Warsh: Standoff with Russian more perilous than you think

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Hanging over Donald Trump’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping last week was the warning of Graham Allison’s book Destined for War, Can America and China Avoid The Thucydides’ Trap? (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017). The book won’t be in stores for another month, but as long ago as 2013 Xi was talking about the metaphor, well before an early version of the Harvard government professor’s argument appeared in The Atlantic.

What has happened historically when a rising power threatens a ruling one? “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable,” Thucydides wrote in his History of the Peloponnesian War. In the 2,400 years since, Allison has found, 12 of 16 such cases have ended in war.

After boasting to the Financial Times, “If China is not going to solve North Korea, we will,” Trump reinforced the message by striking a Syrian airfield while Xi visited him in Florida. Do you wonder why Bashar Assad chose last week to attack a rebellious village with nerve gas? A senior White House official told The Wall Street Journal that the gesture was “bigger than Syria” – representative of how the American president wants to be seen by other leaders. “It is important that people understand this is a different administration [from that of Barack Obama].”

(Different in more ways than one, the spokesman might have added. Trump sought last week to reduce quarrelling among his most senior advisers. How must the president’s record-low favorability rankings in opinion polls complicate the way he is seen by other leaders?)

The defect in The Thucydides Trap is the faulty map it generates. The U.S. is facing not just a single rising power on the world stage, but a diminished and angry giant as well in the form of still-powerful Russia. It has become the habit of much of the U.S. media to tune out Russian President Vladimir Putin on grounds that he does not play by American rules. He murders journalists and opponents, it is said, conducts wars against his neighbors, controls the media, games elections, and has become “President for Life.” Just last week, a Russian court banned as “extremist” an image of the Russian president wearing lipstick, eye-shadow, and false eyelashes, The New York Times reported.

Why not also view Putin as a serious political leader with serious issues governing a nation seeking a new role in the world? One set of these has to do with shaping norms and rules of post-communist civil society. Another set concerns the nation’s economic prospects. Perhaps the most serious of all has to do with the maintenance of Russian’s defense policy – its nuclear deterrent force, in particular. In this respect, The Thucydides Trap misses the point pretty badly.

It’s been 30 years since I consulted an issue of Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The magazine was familiar reading in my youth, when the minute hand on its iconic doomsday clock was set a few minutes before midnight – two, or three, or seven, depending on the circumstances.

For a few years after 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved into 15 independent states, the clock showed a comforting 17 minutes before the hour. The peril has been growing ever since. Earlier this year the editors moved the interval to two-and-a-half minutes – the most alarming warning since the high-peril year of 1984.

Last month, BAS authors Hans Kristensen, Matthew McKinzie, and Theodore Postol explained, The U.S. nuclear forces modernization program underway for 20 years has routinely been explained to the public as a means to preserve the safety and reliability of missile warheads. In fact, the program has included an adjustment that makes each refurbished warhead much more likely to destroy its target.

A new device, a “super-fuze,” has been quietly incorporated since 2009 into the Navy’s submarine–based missile warheads as part of a “life-extension” program. These “burst-height compensating” detonators make it up to three times more likely that its blast will destroy its target than their old “fixed–height” triggers.

Because the innovations in the super-fuze appear, to the non-technical eye, to be minor, policymakers outside of the U.S. government (and probably inside the government as well) have completely missed its revolutionary impact on military capabilities and its important implications for global security.

The result, the BAS authors estimated, is that the US today possesses something close to a first-strike capability. Already US nuclear submarines probably patrol with three times the number of enhanced warheads that would be required to destroy the entire fleet of Russian land-based missiles before they could be launched. Yes, the Russians have submarine-based missiles, too. And they are understood to be developing ultra-high-speed underwater missiles that could destroy American harbors.

But the very existence of the possibility of a pre-emptive strike will surely make Russian strategists jumpy, the BAS authors say. And since Russian commanders lack the same system of space-based infrared early-warning satellites as the U.S., they could expect only half as much time as the Americans have in which to decide whether or not they are facing a false alarm – fifteen minutes as opposed to half an hour. A slim margin for error in judgement has become much thinner.

When Science magazine polled experts about the BAS story, two of the most prominent judged the report to be “solid” or “true.” Thomas Karako, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, was unpersuaded. He derided the “breathless exposé language” and dismissed the authors’ concerns about Russia’s discomfiture. You can make an early acquaintance with the March 1 BAS story here, if you like. A wider, fuller examination of the latest chapter in the story of the doomsday clock has only just begun.

David Warsh, a veteran journalist focusing on economic and political matters and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.