Colorful and Threatened necrophiliac

Female American Burying Beetle.

Excerpted and edited from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini.

Series note: The region’s collection of native species is under threat on several fronts, most notably from humanity’s shortsightedness. Humans aren’t giving the natural world the space it needs and deserves. We’re crowding out non-human life, which, in turn, makes nature less productive and us less healthy. Wild New England examines the animals and insects most at risk.

The American Burying Beetle, thanks to the efforts a decade ago by third-graders at St. Michael’s Country Day School in Newport, is Rhode Island’s state insect. The students’ effort helped raise awareness about this orange-spotted insect with an interesting occupation.

After sniffing out a freshly dead animal from up to 2 miles away, the rare beetle, whose continued existence is listed as threatened, joins a mate in burying the carcass, stripping it of fur or feathers, rolling it into a ball, and covering it in oral and anal fluids to preserve it as a shelter and food source for the pair’s litter of larvae.

Nicrophorus americanus, the largest carrion beetle in North America, is native to at least 35 states and the southern borders of three eastern Canadian provinces.

New England stone walls house many creatures

Excerpted/edited from an ecoRI News article by Colleen Cronin

LITTLE COMPTON, R.I.

A look at a stone wall on Roger and Gail Greene’s property — they guessed the structure dates back to the early 1800s or even late 1700s — suggests that every rock and cranny is a world unto its own.

A black cherry tree stretched its way up and out from underneath — a gift likely planted by a bird who had perched on its stones decades ago, Roger said. Minty green lichen made splotches on gray rocks. A pickerel frog with skin like a snake hopped its way through leaf litter and low grasses to a hiding space before an ecoRI News reporter could get a good photo.

Stone walls originally marked the boundaries of farms, but now they have become homes to many different types of creatures.

Nature-based ways to mitigate disasters

A coastal salt marsh in East Lyme, Conn., along Long Island Sound. Restoring coastal wetlands helps reduce the damage from storms and rising seas associated with global warming. (Photo by Alex756 )

Excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini

“A new global assessment of scientific literature led by researchers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst found that nature-based solutions (NBS) are an economically effective method to mitigate risks from a range of disasters, including floods, hurricanes, and heat waves — all which are expected to intensify as the planet continues to warm.

“NBS solutions are interventions where an ecosystem is either preserved, sustainably managed, or restored to provide benefits to society and to nature. For instance, they can mitigate risk from a natural disaster, or facilitate climate mitigation and adaptation. They have emerged in combination with or as an alternative to engineering-based solutions, such as restoring wetlands to address coastal flooding rather than building a seawall.’’

Those jumping worms

Jumping worms

-- Photo by Njh5880

Excerpted from an ecoRI News article

CRANSTON, R.I.

“An infestation of jumping worms, also known as snake worms, has forced the Rhode Island Wild Plant Society to cancel its August native plant sale.

Pat Foley, president of RIWPS, wrote in an email, ‘We have decided to cancel our upcoming native plant sale. Based on conversations I had this week with the volunteers planning the sale, we learned that invasive ‘jumping worms’ were discovered in some of the plant trays we were readying for the sale.’

“Even though the invasive worms look similar to the region’s more common earthworm, their behavior easily identifies them. They slither through the grass like snakes and jump away if they are disturbed. In their native Korea and Japan, they are called Asian jumping worms.’’

Invasive species are crowding out New England’s native species

An Asian shore crab

Multiflora rose

Text excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini

“Invasive Asian shore crabs are outcompeting young lobsters. Invasive snake worms and hammerhead worms are burying themselves deeper into southern New England, where the former consumes the top layer of soil and dead leaves where the seeds of plants germinate, and the latter is toxic and transmits harmful parasites to humans and animals.

“Invasive multiflora rose and oriental bittersweet have long been embedded in the region, crowding out native vegetation and strangling trees. Some Rhode Island nurseries and garden centers still sell foreign species that don’t mix well with local flora and fauna.

“The spread of invasive species has long been recognized as a global threat to the environment, the economy, and people. Last summer, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) for the United Nations issued a global assessment providing clear evidence of this growing threat.’’

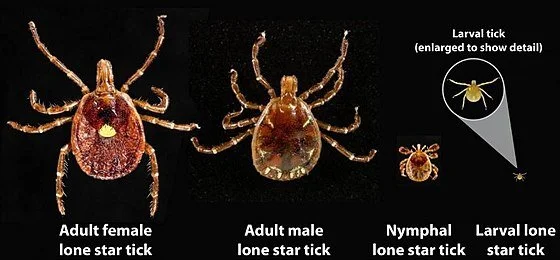

Another invader from the South

Cliff Vanover knew something was wrong one night while traveling in upstate New York in 1995. His palms got itchy, then he got hives, then ‘my body was one solid hive,’ he said. He had gone into anaphylaxis, a severe allergic reaction.

“His wife had antihistamines for her own allergies, so he took some and the symptoms subsided. But then it happened again. ‘I had no allergies at the time,’ Vanover said, so he went to an allergist, who did a series of scratch tests. The Charlestown, R.I., resident learned he was allergic to beef, lamb, and pork.

“Although there was no name for it three decades ago, when Vanover contracted it, he had what is now known as alpha-gal syndrome. It’s caused by the bite of a lone star tick, and it’s going to become a lot more prevalent here in New England {as they move north}.’’

To read the full article, by Bonnie Phillips, please hit this link.

Trying to save horseshoe crabs

Horseshoe crabs mating.

Edited from a ecoRI News article by Frank Carini

“Ancient creatures with 12 legs, 10 eyes, and blue blood were once so prevalent on southern New England beaches that people, including children, were paid to kill them.

“Their helmet-like bodies can still be seen along the region’s coastline and around its salt marshes, but in a fraction of the numbers witnessed seven decades ago. There are several reasons why.

“In the 1950s coastal New England paid fishermen and others bounties to kill the up to 2-feet-long arachnids — horseshoe crabs are more closely related to spiders, scorpions and ticks than to crabs — because they interfered with human enjoyment of the shore and were viewed as shellfish predators….

“People, not just fishermen, were reportedly encouraged to toss horseshoe crabs above the high-tide line, so they would dry out and die. They were labeled ‘pests’ and ground up for fertilizer. Beachfront property owners were apparently concerned the creature’s presence and their decaying death would impact real estate values.

{Horseshoe crabs are harvested for their blood’s medical applications.}

“Those ignorant days may be over, but horseshoe crabs are facing other threats to their existence.’’

“The Center for Biological Diversity, an Arizona-based nonprofit, and 22 partner organizations recently petitioned NOAA Fisheries to list the Atlantic horseshoe crab as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act….’’

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

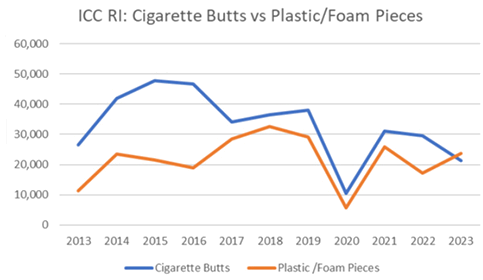

Plastic pieces edge out cigarette butts as beach waste in Rhode Island

Pieces of plastic on beach.

Text from ecoRI News

“For the first time in the history of Rhode Island’s participation in the International Coastal Cleanup program, cigarette butts were not the item most collected by volunteer participants. Instead, small plastic and foam pieces — those pulverized bits that accumulate in wrack lines — took the lead, according to Save The Bay’s recently released 2023 International Coastal Cleanup Report.

“‘When this project started over 35 years ago, the focus was on recording the most common types of identifiable trash so that we could get a picture of what was littering our shores and where it was coming from,’ Save The Bay volunteer and internship manager July Lewis said. ‘In terms of the number of items picked up, cigarette butts were always at the top of the list.”’

“Last year, however, 2,830 local volunteers collected 23,468 plastic and foam pieces — and 21,165 cigarette butts.’’

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

— Save The Bay graphic

Mary Lhowe: The ‘lunchbox’ from offshore wind turbines

Text from ecoRI News article by Mary Lhowe

“Opponents of offshore wind offer different reasons for their position: fear of impacts on the marine ecology; fear of loss of income for fishers; fear of loss of tourism dollars and private property values due to the sight of the turbines on the horizon.

“The cloudy threat of wind projects off the New England coast comes with a golden — not silver — lining. That gold would arrive in the form of millions of dollars contractually promised to communities by developers in the form of mitigations, sometimes through a mechanism called host community or good neighbor agreements.

Even the towns and historic property owners who dread wind farms but yearn for funds to do worthy projects could be excused for reacting to mitigation deals in similar fashion to the character Gaz in the movie The Full Monty. Watching men audition for a new amateur dance troupe, Gaz observes the impressive talents of one particular auditioner, and mutters, “Gentlemen, the lunchbox has landed.”

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Frank Carini: We need bats

An Eastern Small-Footed Bat, of a species found in New England.

Hollywood and literature routinely portray bats as blood-sucking monsters. It’s entertaining, but in reality, humans are a much bigger threat to these winged mammals than they are to us. In fact, their presence is beneficial in numerous ways.

Bats play an important role in the control of mosquitoes and agricultural pests. They save the United States about $1 billion annually in pest control. Bats in the Southwest and other warm areas around the world help plants grow by pollinating flowers. When nectar-drinking bats stick their long noses into flowers, they become covered in pollen that they then bring to other flowers. Through pollination, bats help grow avocados, bananas, and mangoes. In all, some 300 species of fruit depend on bats for pollination.

Also, of the 1,400 or so bat species worldwide, only three — the Common Vampire Bat, the Hairy-Legged Vampire Bat and the White-Winged Vampire Bat — feed solely on blood, mostly that of birds. You would have to travel much further south than southern New England to find one….

The eight species of bats that can be found in Rhode Island are divided into two classes: tree bats (Eastern Red Bat, Hoary Bat, and Silver-Haired Bat) and hibernators (Little Brown Bat, Big Brown Bat, Tricolored Bat, Northern Long-Eared Bat, and Eastern Small-Footed Bat). They are all insectivores.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

The great invasion

Text from article by Frank Carini in ecoRI news

A worldwide scientific intergovernmental group on biodiversity, which included a professor from the University of Rhode Island, provides evidence of the global spread and destruction caused by invasive alien species and recommends policy options to deal with the challenges of biological invasions.

The comprehensive report, released Sept. 4 by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for the United Nations, found the threat posed by invasive species introduced into new ecosystems is “enormous.”

In 2019, invasive species caused an estimated $423 billion in damages to nature, food sources, and human health. These alien invaders have also contributed to 60% of recorded animal and plant extinctions, and were the sole factor in 16% of extinctions, according to the report.

“This is the first global report on invasive alien species anywhere,” said Laura Meyerson, a URI professor in natural resources science and a contributing lead author on the report. “It’s truly an effort of scientists from around the world. The data touch on every world region, every biome and all major taxa — plants, vertebrates, invertebrates, micro-organisms, fungi.”

Invasive species pose to a threat biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human well-being. The report is designed to raise public awareness to “underpin action to mitigate the impacts of invasive alien species.”

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Frank Carini: In search of dragons and damsels

Dragonflies during migration

— Photo by Shyamal

From ecoRI.org

SOUTH KINGSTOWN, R.I. — Virginia Brown and Nina Briggs have been hunting dragons for three decades. They have spotted thousands. Capturing one is a bit more difficult. They can be up in a tree out of reach or hidden in leaf litter below. Catching one by hand is toilsome.

These dragons, glistening in shades of black, blue, brown, green, red, and yellow, are some of the most colorful creatures on the planet, with intricate patterns of stripes and spots. To Brown and Briggs, they are also some of the most elegant insects on Earth.

These aerial assassins have been around for about 300 million years. They survived the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. They have, so far, survived humankind’s destructive nature.

They can be found buzzing around in the swampy wilds of Rhode Island. In the summer, these winged acrobats perform stunts above and around ponds, lakes, streams, bogs, marshes, and rivers.

On a recent Saturday morning at the Great Swamp Management Area off Great Neck Road here,where the two conservationists guide public “hunts,” the longtime Rhode Island residents took this ecoRI News reporter on a 2-hour adventure in search of dragonflies and damselflies. See Brown’s book about these creatures.

My guides noted their favorite insects demonstrate charismatic behavior, possess an ancient evolutionary history, and play an important role in the ecology of aquatic habitats.

Virginia Brown, whose hat aptly captures her fondness for dragonflies and damselflies, has a keen eye for finding her favorite insects. To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Frank Carini is senior reporter and co-founder of ecoRI News

Damselfly

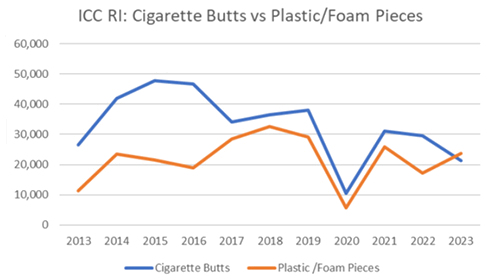

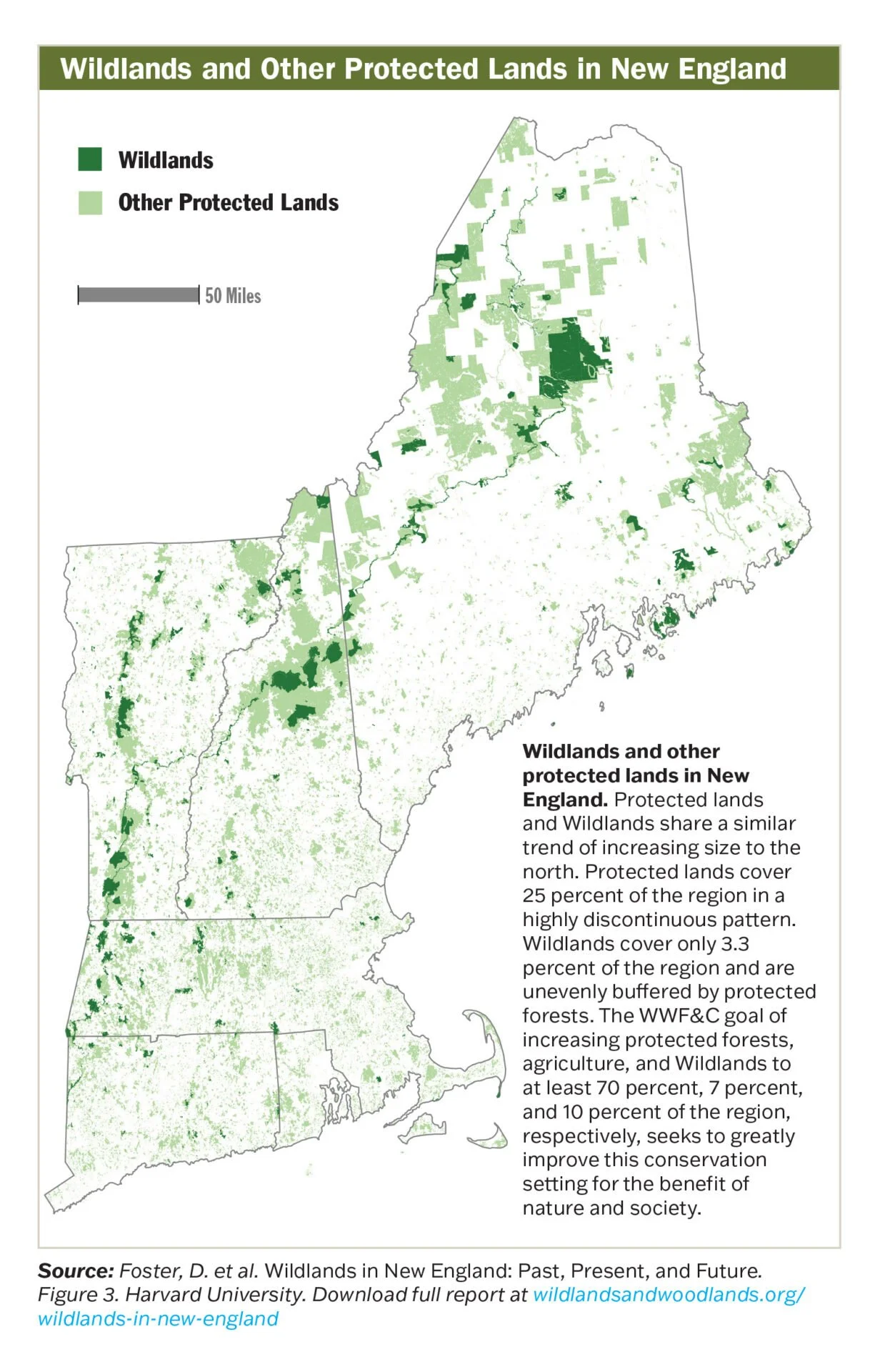

Study says New England needs to protect much more wildlands

Excerpted from ecoRI News by Rob Smith

PETERSHAM, Mass. (home of Harvard University’s research forest)

“New England isn’t conserving enough wildlands to mitigate climate change or meet conservation goals.

“That’s according to a new study released late last month by Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands and Communities (WWF&C), a coalition group of conservation organizations, educational institutions, local governments and private nonprofits.

“The first-of-its-kind analysis, performed jointly by (the} Harvard Forest of Harvard University, the Northeast Wilderness Trust and Highstead Foundation, examined how much wildlands — tracts of land where the management policy is to leave nature ‘alone’ and allow natural processes to prevail without human interference — are preserved across the region, and the answer is: not much.

“‘The wild condition of the land derives not from the land’s history, but from its freedom to operate untrammeled, today and in the future,’ wrote the study’s authors.

“The study lays out three criteria for land to meet its wildlands definition: the land must have a deliberate wildland purpose; it must be allowed to mature freely under prevailing environmental conditions with minimal human intervention; and it must be protected in perpetuity.

“The key factor in wildlands is time. In New England, where much of the land has been developed and used, wildlands are more likely to develop via natural rewilding, an ecological restoration practice that aims at reducing the influence of humans on ecosystems. Wildlands are more likely to look like recently clear-cut areas or former pastures than old growth forest.

“Only 1.3 million acres, around 3.3% of New England’s total land area, protects wildlands across 426 individual properties, with much of it limited to the remote and rural areas of the region, a band of land that stretches from northwestern Connecticut to Baxter State Park in Maine. Meanwhile WWF&C has set a goal of preserving 10% of the region as wildlands.’’

Diorama at the The Fisher Museum at the Harvard Forest, which offers exhibits on current research as well as 23 dioramas portraying the history, conservation and management of New England woodlands.

Studying New England birds’ perilous migrations

Male (left) and female (right) American goldfinches at a thistle feeder. The American goldfinch can be found in Rhode Island year-round, though some individuals migrate south during the non-breeding season.

From an article by Bonnie Phillips in ecoRI News:

“Scientists and biologists know much more about bird migration now, why they do it and, for the most part, how. Almost half of all birds migrate in some form or another. Many migrate at night, when the weather is calmer and there are fewer predators. Some birds travel as far as 7,000 miles nonstop, and others return to the same locations year after year.

“Migration takes a toll on birds — it’s a dangerous time, when the exhausted birds are especially vulnerable to predators, deteriorating habitat, and climate change. Researchers are realizing that it’s vital to understand migration patterns and habitat usage to prevent further loss of already declining bird populations.

“‘The more bird migration comes into focus, the more we realize that, to conserve our declining birds, we must focus our attention on these strenuous and perilous periods in their lives,’ said Charles Clarkson, director of avian research at the Audubon Society of Rhode Island.

“The society’s recently released State of Our Birds Part II report is a start toward examining the habits of birds that use Audubon’s 9,500 acres of refuges as stopovers on their migrations. Research suggests Rhode Island — the {rural/exurban} western part of the state in particular — is more important than any other New England location for migrating birds.’’

To read the full article, please hit this link.

#birds #Rhode Island

‘Ropeless’ fishing has promise to protect whales but adds costs, complications to industry

Text from article by Mary Lhowe in ecoRI News.

A handful of Rhode Island lobster fishermen are working this season with federal regulators to use and study some complex and early stage equipment that is intended, eventually, to greatly reduce entanglements and deaths of whales.

The experimental equipment for this so-called “ropeless” fishing would eliminate the vertical ropes — or “lines” — running down the water column from buoys on the surface to lines connecting a series of traps on the seafloor. The existing function of buoys and vertical lines — to find and retrieve traps — would be replaced under a new system by computerized acoustic signals from boats to the seafloor and geopositioning via cell signals or satellites.

Using federal experimental fishing permits, three Port Judith-based lobstermen are struggling to use the new gear, borrowed from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), a branch of NOAA Fisheries.

To read entire article, please hit this link.

Frank Carini: The staggering hypocrisy of the anti-offshore wind farm crowd

From Frank Carini’s column “Whale of a Tale: Local Anti-Wind Crowd Spins Yarns,’’ in ecoRI News (ecori.org)

”No energy source is benign. From installation to operation, they all come with consequences — environmental, societal, and cultural. Some more than others. Legitimate concerns (e.g., not infringing upon whale migration corridors) must be studied, discussed, mitigated, and/or avoided. Renewable energy shouldn’t be called clean, but it is a whole lot cleaner than fossil fuels….

“The concerns of southern New England’s anti-offshore wind crowd, however, never spill over to the polluting gas and oil platforms that mar many of the waters off the U.S. coast, especially in the Gulf of Mexico. Probably because there are no such rigs in Rhode Island Sound.

“They don’t mention sonar {which can disturb marine mammals} is used to detect leaks from offshore fossil fuel infrastructure. They fail to note ocean military training drills use sonar, and live munitions. They disregard the fact the primary causes of mortality and serious injury for many whales, most notably the North Atlantic right whale, are from entanglements with fishing gear and vessel strikes.

“Even though data show that North Atlantic right whale mortalities from fishing entanglements continue to occur at levels five times higher than the species can withstand, the anti-wind crowd isn’t calling for fishing gear to be pulled from local waters or the use of ropeless fishing technology made mandatory. They aren’t demanding vessels be equipped with technology that monitors the presence of whales in shipping lanes.

“They ignore the fact the development of offshore wind is the most scrutinized form of renewable energy. After reading this column, they will allege I and/or ecoRI News are in the pocket of Big Wind. We’re not. (A few wind energy companies have advertised with us, but they didn’t spend nearly enough to bankroll a golden parachute, or even a reporter’s salary for a month.)

“The anti-wind crowd doesn’t offer any real solutions to drastically reduce the amount of heat-trapping, polluting, and health-harming greenhouse gases that humans are relentlessly spewing into the atmosphere.’’

To read the full column, please hit this link.

Trying to understand offshore wind turbines' ecological effects

Wind energy lease areas off the southern coasts of Massachusetts and Rhode Island as of October, 2022

From Mary Lhowe’s very valuable article in ecoRI News:

“{C}an wind turbines off the coast of Rhode Island live up to their renewable energy promise? And what effects will they have on life in the sea?

“Hundreds of experts from the U.S. Department of the Interior down to local fishermen and town planners are puzzling over these questions, especially now, during the permitting and approval process of the Revolution Wind project, in which developers Ørsted and Eversource hope to install up to 100 wind turbines on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) about 18 miles southeast of Point Judith. Cables to transmit power to the grid would make landfall in North Kingstown, and the project is expected to be online by 2025. The Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the project was published last fall.’’

Frank Carini: Navy worried about rising seas at Naval Station Newport

View of Naval Station Newport (aka Newport Navy Base), which includes parts of Newport and Middletown.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The U.S. Department of Defense has concerns about sea-level rise and other climate-change impacts on Naval Station Newport, along the shores of Aquidneck Island.

“Since 2010, the Department of Defense has acknowledged that the planet’s changing climate has a dramatic effect on our missions, plans and installations,” Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III said last year. “The department will immediately take appropriate policy actions to prioritize climate change considerations in our activities and risk assessments to mitigate this driver of insecurity.”

The Aquidneck Island Climate Caucus, led by Rep. Terri Cortvriend, D-Portsmouth, recently hosted a discussion about resiliency plans for the Naval station.

The Oct. 23 online event, titled “Newport Naval Station Resilience: What’s the Plan?” featured Cornelia Mueller, community planning liaison officer at Naval Station Newport, and Pam Rubinoff, a coastal resilience expert at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

Mueller said the climate crisis is a serious problem for the military training installation and the three municipalities — Portsmouth, Middletown, and Newport — that share space on Aquidneck Island. She noted it’s both an economic and safety issue for the largest island in Narragansett Bay.

To address the local challenges presented by the climate crisis, the Navy worked with the University of Rhode Island, municipal officials, and local stakeholders, such as the Aquidneck Land Trust and the Eastern Rhode Island Conservation District, to create a Military Installation Resilience Review for short-term preparedness and long-term planning. Much of the recently completed review is not available for public consumption, but a 12-page outline can be found here.

The review’s researchers ran 12 scenarios with 1 foot, 3 feet, and 5 feet of sea-level rise against modeled weather events. The modeling also included “significant” expansion planned for Naval Station Newport during the next 10 years, which will include more National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ships and a larger Coast Guard presence, according to Mueller.

The work noted the Navy and other Aquidneck Island entities share concerns. For example, the Navy relies on the Newport Water Division for drinking water and on the Long Wharf Pump Station, owned by the city of Newport, for its wastewater treatment.

The kind of climate work Austin spoke about during his 2021 visit to Virginia’s Naval Station Norfolk is taking place at Navy Region Mid-Atlantic installations, including Naval Station Newport.

The Navy’s response to the climate crisis has included natural solutions, such as dune restoration and better protecting coastal marshes and shoreline vegetation. Man-made solutions have included berms and flood walls.

Mueller said Naval Station Newport is hoping to restore Elizabeth Brook. The waterway, which begins in Middletown and empties near Gate 2 in Newport, is causing flooding problems for both municipalities and the Navy. She also noted there are plans to build buffers, create green space, and use man-made structures to address the increased flooding being experienced on Aquidneck Island.

The review found 152 “assets of concern,” such as generators, wastewater treatment facilities, and communications, energy, and transportation infrastructure. The review also found it would take 14 hours to evacuate Aquidneck Island during clear skies.

Rubinoff said there are significant concerns that need to be addressed and the solutions will require island-wide collaboration.

The Department of Defense (DOD) has identified climate change as a critical national security issue. The crisis will continue to amplify operational demands on the force, degrade installations and infrastructure, increase health risks to service members, and require modifications to existing and planned equipment needs.

The agency has noted that the past decade, 2011-2020, was the warmest on record. It has said the increase in thermal energy trapped in the atmosphere is having enormous consequences around the globe.

The DOD’s 2022 Climate Adaptation Report assesses climate exposure related to eight hazards: coastal flooding, riverine flooding, heat, drought, energy demand, land degradation, wildfire, and historical extreme weather events. It also notes that the agency is working to incorporate environmental justice into the implementation of its evolving Climate Adaptation Plan.

“Rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and more frequent, extreme, and unpredictable weather conditions caused by climate change are worsening existing security risks and creating new challenges,” according to the latest version of the report. “Climate change is increasing the demand and scope for military operations at home and around the world. At the same time, it is undermining military readiness and imposing increasingly unsustainable costs on the Department of Defense.”

The Aquidneck Island Climate Caucus is planning additional discussions to be held over the winter, on topics including updates on federal legislation, 2023 state legislative goals, ocean health, offshore wind turbines are coming, “Act on Climate: What are the immediate steps?” and “Where are we going with fossil fuels?”

Frank Carini is co-founder and senior reporter of ecoRI News.

Rob Smith: Ferries, charter boats along East Coast may have to slow down to protect endangered whale species

The New London, Conn., ferry terminal, which serves the Cross Sound Ferry and the Block Island Express, as viewed from across the Thames River. Both ferry services would be affected by proposed federal rules to help protect North Atlantic Right Whales.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NARRAGANSETT, R.I.

Ferries and charter boats might have to move a lot slower along the New England coast during the off-season if federal regulators accept new nautical speed limits to protect an endangered species of whale.

Officials with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have proposed restricting existing nautical speed limits to 10 knots per hour for all vessels longer than 35 feet. If approved, the new rule would go into effect between Nov. 1 and May 30 and apply to all vessels sailing along the Atlantic seaboard from Massachusetts to North Carolina.

The rule is intended to curb the amount of vessel strikes on the Atlantic’s already limited North Atlantic Right Whale population, which is close to extinction. NOAA estimates at least four right whales have died from colliding with marine vessels since 2017.

“The biggest impact to charter boats is the loss of fishing time for our clients,” said Capt. Rick Bellavance, president of the Rhode Island Party and Charter Boat Association. “If we’re driving 10 miles an hour instead of 15, that’s 5 miles of travel every hour. It could be a half hour or an hour each day of less fishing and more driving.”

The off season isn’t quite as off it used to be. Bellavance says more and more customers charter boats to fish for tautog, also known as blackfish, which has had a resurgence thanks to, among other things, careful conservation by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), and is almost an attraction for the state in November and December.

Daily ferry service to Block Island could also be curtailed under the new rules. Currently the Block Island Ferry runs eight hour-long trips from the Port of Galilee to the island and back every weekday, with the average vessel speed clocking 16 knots per hour. Under the new restrictions, the daily ferry ride could take upwards of 90 minutes per one-way trip, with a reduced number of trips per day.

Block Island Ferry declined to comment for this article.

Protecting the right whales

Considered by NOAA to be “one of the world’s most endangered large whale species,” North Atlantic Right Whales feed in coastal waters ranging from New England to Newfoundland from spring to autumn. They then migrate to calving grounds off the southern United States, near the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida.

As of 2021 it is estimated there are only 350 North Atlantic Right Whales left worldwide. Once a plentiful species throughout the Atlantic, their populations were culled over the centuries due to aggressive whale hunters in the Northeast, who called them “right whales” because they were easily killed and their corpses floated to the surface.

Now right whales are protected under federal law and the Endangered Species Act, but the population has struggled to bounce back, with only an estimated 42 calves being born since 2017. Overall the right whale population has significantly declined since 2010, and 54 right whales have died or been seriously injured since 2017.

The real threat to right whales is no longer crusty old New England fishermen. According to federal officials, the real threat comes from entanglement in commercial fishing nets and vessel collisions. NOAA estimates over 85 percent of all right whales have been entangled in fishing nets at least once. The agency also estimates at least four whales have died because of vessel collisions since 2017 — and that number may be higher. NOAA estimates two-thirds of whale deaths go unreported.

“Collisions with vessels continue to impede North Atlantic right whale recovery. [Vessel speed limits are] necessary to stabilize the ongoing right whale population decline, in combination with other efforts to address right whale entanglement and vessel strikes in the U.S. and Canada,” said Janet Coit, assistant administrator for NOAA Fisheries.

Speed limits to curb collisions and protect right whales have existed since 2008, but the restrictions limited them to narrow geographic areas – for Rhode Island it only applied in waters south of Block Island, not affecting most marine traffic going in and out of Narragansett Bay – and ships greater than 65 feet long.

A risk analysis performed by NOAA suggested expanding vessel speed restrictions in the areas of highest risks could reduce right whale mortalities from vessel strikes by 27.5 percent.

The economic impact would also be minimal, according to NOAA. The agency’s economic impact report estimated the direct costs and impacts on transit times would cost the economy $28.3 million to $39.4 million annually, with much of that amount borne by the commercial shipping industry.

RIDEM, which owns and maintains the Port of Galilee, estimated the impact on commercial fishing vessels operating out of the port would be minimal. “Vessels in that size range aren’t traveling much faster than 10 knots anyway, even when transiting,” said DEM spokesman Mike Healey.

Not all agree. Bellavance thinks it will hurt the charter boat owners, who need the most business.

“There’s a smaller group of folks who do this to provide for their families, that’s their job,” said Bellavance. “Those are the ones that are impacted when you start to mess with the winter season, cause they’re still trying to go fishing year-round.”

NOAA is accepting public comment on the proposed rule until the end of October.

Rob Smith is an ecoRI staffer.

Mike Freeman: The mysterious and alarming decline of muskrats - much needed waterway engineers

Muskrat feeding.

— Photo by mikroskops

No one would call muskrats “charismatic megafauna.” They’re pudgy, small and just rat-like enough. Semiaquatic, they inhabit sloughs, creeks, and swamps people rarely visit. Muskrats have been considered so prevalent and unremarkable that even people in tune with environmental goings-on have been unaware of the species’ 50-year decline. Biologists noted the nationwide trend early through trappers’ harvest data, but earnest study is a recent phenomenon.

“It would be like robins suddenly declining,” said John Crockett, a University of Rhode Island graduate student studying the state’s muskrat distribution. “No one ever thought muskrats would be in trouble.”

Muskrat lodge built from vegetation

In trouble they are, though, with unsettling implications. The first of these are the animals themselves and their ecological role. Muskrats feed on wetland vegetation and build covered winter “lodges” from it. This opens wetlands up, thinning plants such as cattails and bulrushes to create what Crockett called “patchy ecosystems” that sustain greater biodiversity, the way big wind events, pest outbreaks, and managed timber cuts open forests to new growth, attracting different suites of birds and plant communities than uniform woodlands.

With dwindling muskrat populations, dense vegetation blunts water flow, changes oxygen levels, and can pare back fish and invertebrate life.

“Muskrats are crucial wetland engineers,” said Laken Ganoe, another URI Ph.D. candidate, who published a 2020 paper on muskrat decline while at Penn State. “Similar to beavers, their activity can change hydrology, stream bank structure, and help maintain functioning wetlands. They’re also a key prey source for species such as mink, birds of prey, and raccoon. The wetlands they help maintain provide ecosystem services such as water filtration and air purification, and declining muskrat populations can throw these out of balance.”

In southern New England, muskrats inhabit fresh and brackish water, from nameless rills to big rivers to salt marshes. Their increasingly diminished presence is bad enough, but equally worrisome is why it is happening, in large part because that isn’t known.

Laurence C. Smith of the Institute at Brown (University) for Environment and Society has started a DNA study to determine muskrat presence in Rhode Island waterways. He described the current science, which isn’t far beyond the spit-balling phase.

“Researchers are just beginning to study this problem and there are numerous hypotheses being tested, including disease, habitat loss, and climate change,” he said.

Crockett added nuance, saying that habitat fragmentation and isolation are plagues for all species including muskrats, and that ecosystem degradation, including water quality, is another potential culprit. Ganoe’s Pennsylvania study looked at traditional muskrat diseases such as tularemia, along with ailments that might relate to cyanobacteria and legacy industrial chemicals. While she found various levels of concern, nothing resembling a widespread killer turned up. Across the United States and Canada, she said, there seems to be consensus that “there’s not one overarching cause of the decline, but rather a dozen puzzle pieces working in conjunction.”

That muskrats’ woes result from a grim grab bag of sprawl, industry, pollution and climate change is likely, which only compounds the worry, as muskrats have already proven that they are built for the Anthropocene. Highly prolific and mobile, the animals thrived in the notoriously unregulated mid-20th Century, but are listing now. Why is unknown, but muskrats once rated with pigeons and cockroaches as the creatures most likely to survive us, so finding that answer is imperative.

Trapper harvest data isn’t infallible, but biologists gain much from it. Charlie Brown, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s recently retired furbearer biologist, studied harvest data throughout his 31-year professional tenure.

“It’s difficult to rely on harvest data exclusively,” he said. “But it’s valuable. Rhode Island requires exact harvest data in order to renew your license … whereas that information is voluntary in other states, so we have very specific numbers going back to 1949.”

In the 1950s, Brown said, Rhode Island trappers took 10,000 muskrats a year. During the 2019-2020 season, just 47 were killed. Declining trapper numbers affect that, but not enough for a drop that steep.

There’s some counter-intuition to wrestle here. On paper, conditions favor muskrats more now than in the 1950s to ’70s, when wetlands were blithely drained and factories dumped effluent everywhere. In Barrington, R.I., where Brown grew up, a lace dye company made Bullocks Point Cove turn whatever color stain it used that day.

“But muskrats were still there,” Brown said. “And in big numbers.”

Crockett said even today one of the highest muskrat concentrations he has found is on the Pawtuxet River right under Interstate 95.

Wetland acreage, too, has remained stable during the muskrats’ decline period. That marshes are no longer drained and rivers no longer run purple is great news. Yet, muskrats boomed during these conditions and badly falter now.

With research just ramping up, speculation remains the only map. Waters are still loaded with farm and lawn runoff, along with plastic pollution, though no direct evidence currently links these with muskrat decline. Invasive aquatic flora jumps out, too. Smith is testing the replacement of native plants like cattails (Typha) by phragmites, the invasive reeds that now dominate fresh and brackish waters.

“Phragmites creates more sterile wetlands and chokes out open-water patches favored by muskrats,” he said.

Laura Meyerson, a URI professor whose research focuses on invasive species, with a particular emphasis on plants, points to phragmites and other invasive flora as potential reason for muskrat decline.

“Water chestnut is particularly nasty,” she said. “It grows floating mats that have little nutritional value. In fresh and salt water, phragmites has outcompeted Typha. Muskrats rely on Typha for their carbohydrate-rich rhizomes [roots] and the leaves and stems to build their lodges.”

Mike Freeman is an ecoRI News contributing reporter.