David Warsh: What went wrong in Epidemiologists’ War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is clear now that United States has let the coronavirus get away to a far greater extent than any other industrial democracy. There are many different stories about what other countries did right. What did the U.S. do wrong?

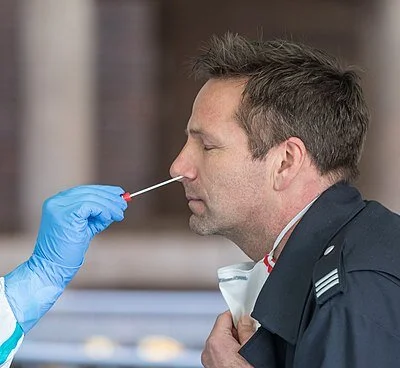

When the worst of it is finally over, it will be worth looking into the simplest technology of all, the wearing of masks.

What might have been different if, from the very beginning, public health officials had emphasized physical distancing rather than social distancing, and, especially, the wearing of masks indoors, everywhere and always?

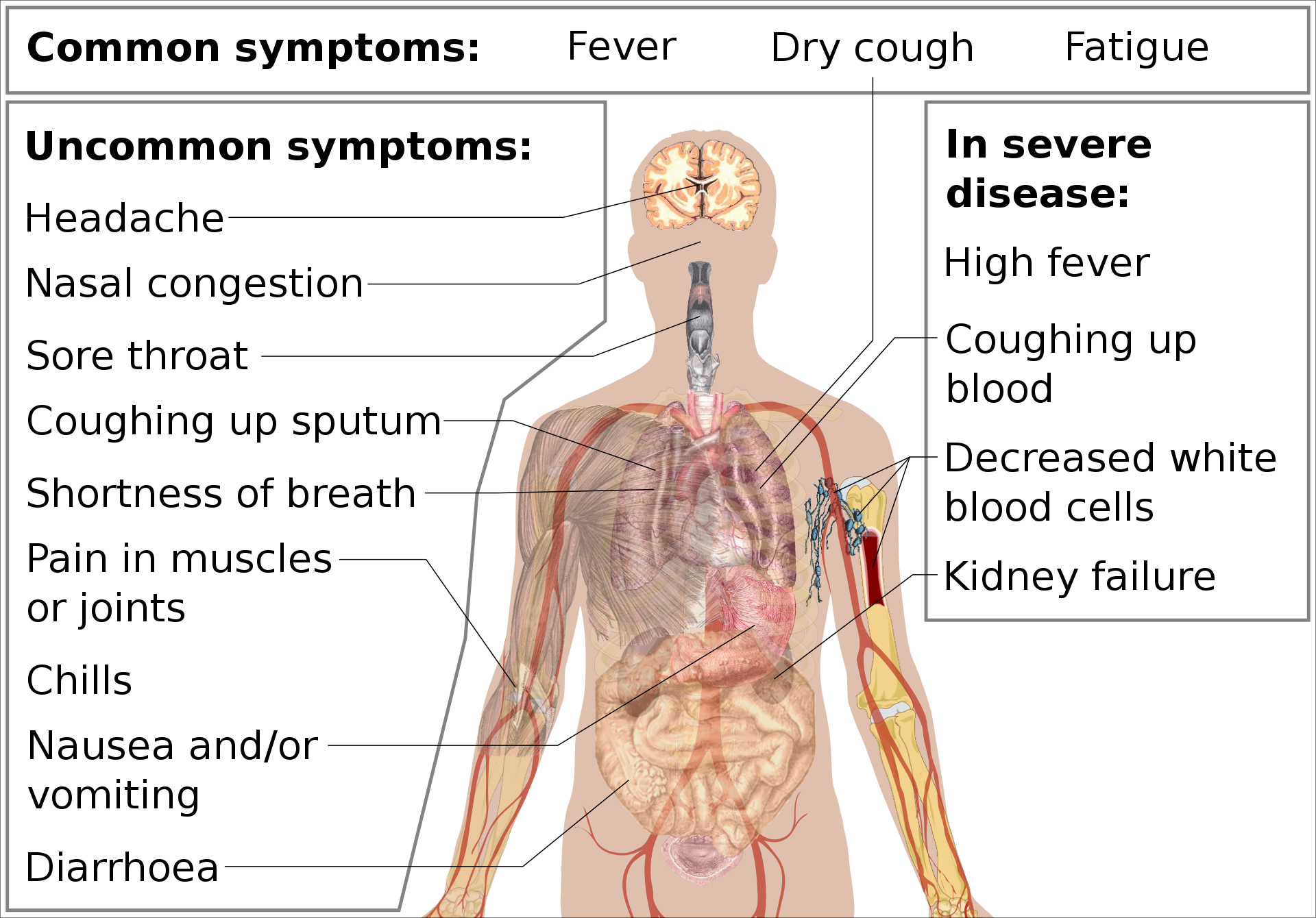

Even today, remarkably little research is done into where and how transmission of the COVID-19 virus actually occurs – at least to judge from newspaper reports. Typical was a lengthy and thorough account last week by David Leonhardt, of The New York Times, and several other staffers.

Acknowledging that previous success at containing viruses has led to a measure of overconfidence that a serious global pandemic was unlikely, Leonhardt supposed that an initial surge may have been unavoidable. What came next he divided into four kinds of failures: travel policies that fell short; a “double testing failure”; a “double mask failure”; and, of course, a failure of leadership.

The American test, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which worked by amplifying the virus’s genetic material, required more than a month longer to be declared effective, compared to a less elaborate version developed in Germany. The U.S. test was relatively expensive, and often slow to process. The virus spread faster than tests were available to screen for it.

As for masks, Leonhardt reported, experts couldn’t agree on their merits for the first few months of the pandemic. Manufactured masks were said to be scarce in March and April. Their benefits were said to be modest.

From the outset it was understood that most transmission depended on talking, coughing, sneezing, singing, and cheering. Evidence gradually accumulated that the virus could be transmitted by droplets that hung in the air in closed spaces – in restaurants, and bars, for example, on cruise ships, or in raucous crowds. By May, it became more common for official to urge the wearing of masks.

But Leonhardt cited no evidence of the rate at which outdoor transmission occurred among pedestrians, runners or participants in non-contact sports. Nor did he take account of wide disparities of distance across America among people in cities, suburbs, and country towns. In many areas, most people used common sense, which turned out to be pretty much the same as medical advice.

Instead of becoming ubiquitous indoors and out, as in Asia, or matters of fashion, as in Europe, Leonhardt wrote, masks in the United States became political symbols, “another partisan divide in a highly polarized country,” unwittingly exhibiting the divide himself.

Whether things would have turned out differently had face-coverings been confidently mandated everywhere indoors from the very beginning, and recommended wherever where crowds were unavoidable, is a matter for further research and debate. Not much is known yet about the efficacy of various forms of “lock-down” – office buildings, public-transit, schools, college dormitories.

This much, however, is already clear: very little effort has been spent on discovering what was genuinely dangerous and what was not; still less on communicating to citizens what has been learned. Epidemiologists live to forecast. Economists conduct experiments. Expect the “light touch” policies of the Swedish government to attract increasing attention.

About the failure of leadership in the U.S., Leonhardt is unremitting: in no other high-income country have messages from political leaders been “so mixed and confusing.” Decisive leadership from the White House might have made a decisive difference, but the day after the first American case was diagnosed, President Trump told reporters, “We have it under control.” Since then consensus has only grown more elusive, at least until recently.

Word War I was sometimes called the Chemists’ War, because of the industrially manufactured poison gas employed by both sides, The German General Staff looked after their war production. World War II was the Physicists’ War,” thanks to the advent of radar and, in the end, the atomic bomb. It was equally said to be the Economists’ War, chiefly because of the contribution of the newly developed U.S. National Income and Product Accounts to war materiel planning.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been the Epidemiologists’ War. Next time look for economists to make more of a contribution. And hope for a more prescient and decisive president.

. xxx

The New York Times reported last week it had added 669,000 net new digital subscriptions in the second quarter, bringing total print and digital subscriptions to 6.5 million. Advertising revenues declined 44 percent. Earnings were $23.7 million, or 14 cents a share, down 6 percent from $25.2 million, or 15 cents a share, a year earlier.The news made the pending departure of chief executive Mark Thompson, 63, still more perplexing.

“We’ve proven that it’s possible to create a virtuous circle in which wholehearted investment in high-quality journalism drives deep audience engagement, which in turn drives revenue growth and further investment capacity,” Thompson said. His deputy, Meredith Kopit Levien, 49, will succeed him on Sept. 8, the company announced last month. Kopit Levien told analysts last week that the company believed the overall market for possible subscribers globally was “as large as 100 million.”

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Shailly Gupta Barnes: In crisis, pols focus on helping the rich

Via OtherWords.org

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed fundamental inequalities in this country.

With millions of us hurting — especially the poor and people of color — there’s been widespread public support for bold government action to address long-standing social problems. Unfortunately, our lawmakers haven’t met the overwhelming need to focus on the poor and frontline workers.

Instead, trillions of dollars have been released to financial institutions, corporations, and the wealthy through low-interest loans, federal grants, and tax cuts — all without securing health care, wages, or meaningful income support for the unemployed. This is all unfolding as we enter the worst recession since the Great Depression.

As Callie Greer from the Alabama Poor People’s Campaign reminds us, “This system is not broken. It was never intended to work for us.”

This system treats injuries to the rich as emergencies requiring massive government action, but injuries to the rest of us as bad luck or personal failures. It reflects the belief that an economy that benefits the rich will benefit the rest of us, because it is the rich who run the economy.

It is easy to see how this plays out in policies that directly favor Wall Street, corporations, and the wealthy. But we see it even in policies that appear to be more liberal and equitable.

The CARES Act, for example, provided free testing for coronavirus, but not treatment. It offered unemployment insurance for some who’ve lost their jobs, but not living wages for those still working. It identified essential workers, but didn’t secure them essential protections.

The failure to fully care for workers and the poor is the flip side of the belief that the rich will construct a healthy economy out of this crisis. We see it directly as politicians slash money from public programs during this crisis while refusing to touch the accumulated wealth of the few.

In New York state, Gov. Andrew Cuomo passed an austerity budget that will cut $400 million from the state’s hospitals. In Philadelphia, Mayor Jim Kenney revised the city’s five-year budget to include government layoffs, salary cuts, and cuts to public services. Neither Cuomo’s nor Kenney’s budget made the proactive decision to tax the wealthy.

The same is true in Washington state, where Gov. Jay Inslee has been cutting hundreds of millions from state programs, anticipating major declines in tax revenue. This in a state that’s home to two of the wealthiest people in the world, Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates.

Of course, the rich are not the driving economic force in the country. It has become crystal clear during this pandemic that poor people, including frontline workers, actually fuel this economy. “We may not run this country,” said Rev. Claudia de la Cruz back in 2018, “but we make it run.”

But now we see the early rumblings of people coming together to assert this reality and challenge our faith in the rich.

Health-care workers, students, child-care givers, food-service workers, big-box-store employees, delivery drivers, mail carriers, and others are taking action to call out gross inequities and organize our society differently. Demands to cancel rent and to secure housing for all, universal health care, living wages, guaranteed incomes, and the right to unions are being heard all across the country.

Meeting these demands would not only secure the lives and livelihoods of millions of people — it would begin to release our economy from the suffocating grasp of the wealthy and powerful. Instead of waiting for wealth to trickle down, we would revive our economy by raising up the poor.

When you lift from the bottom, everybody rises.

Shailly Gupta Barnes is the policy director for the Kairos Center and the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival.

Don Pesci: A hypochondriac uncle and credulous Nutmeggers

VERNON, Conn.

Every family should have at least one hypochondriac. Ours was an uncle who washed his hands multiple times before and after meals. He was fastidious about his silverware, examining it minutely for water stains and polishing it at table with his napkin, much to the annoyance of my mother, even thought the silverware was as spotless as a saint.

One Christmas, the dining room table crowded with family and friends, my mother, attempting to extract a roast from the oven, brushed her hand on the pan, yelped, and dropped the roast to the floor. It spun around like a top and came to a rest touching the radiator, which was not spotless. She shot me daggers and said in a pained whisper full of menace, “DON’T TELL ANYONE ABOUT THIS!”

I immediately fell in with her subterfuge. The roast was cleaned of a dust rat, purified, and bought to the table with no one the wiser. I remember wondering at the time how long the prohibition was to last, for I was yearning immediately to tell my brother and sister about the mishap, but only after the multitude had been fed. These things were meant to be shared with others. What a burden! I watched the uncle devour the meat and wondered whether he would drop dead at table or in the bathroom, after cleaning his hands for the fourth time.

The uncle died relatively young, despite the fact that most members of the family lived into deep codgerdom.

My grandfather on my mother’s side died at ninety-something, full of years, grappa and Toscano cigars, which he smoked Ammezzato.

A few years before he passed on, he had sucker-punched a younger man in the pub he used to frequent because the ill-mannered stranger had insulted a Polish friend of his while the two were playing at cards. The local police brought the unconscious stranger to the border of the town and advised him, when he woke from his nap, that should he return to town – ever – he would be arrested .

When the hypochondriac uncle passed away, my mother whispered decorously to me, “Guess the germs finally got him,” adding, “DON’T TELL ANYONE I SAID THAT!”

The uncle was an expert fisherman, and for years I wondered how he could bear to hook worms on his line, until my father told me he only used dry flies, beautiful, fetching, hand-crafted flies. Even so, he had to unhook the fish and drop it into his often-washed wicker basket, which he wore on his waist, like a gunslinger.

This fastidious uncle would have survived in good order the grosser inconveniences of Coronavirus – no hugging, no handshakes, washing hands frequently after touching polluted surfaces, especially plastic, where the deadly virus remains in attack mode for nearly a day, conversing at a safe distance, avoiding crowds, wearing facemasks, telecommuning with a doctor every time the hairs on the back of his neck prick up in fright, usually after listening to some doomsday-physician on 24/7 Coronavirus coverage networks – because he regarded his immediate environment as a familiar septic system of fatal germs.

To wake each morning was to be alert, focused on the micro-microcosm, to be always on one’s guard, rubbing the plate off the silverware.

To a certain extent, Coronavirus has made cowards of us all – also, hypochondriacs of us all. Normalcy, and the economy, too, have fled the pandemic, screeching and screaming. It will not return, the experts tell us, until the dragon has been slain. And, like a cat, the dragon has nine lives. The choices that lie before many of us now appear to be poverty or death. And, as Yogi Berra might have said, “The future ain’t what it used to be.”

Will we survive? Of course we will. But sociability will have received a blow to the solar plexus, and all of us will be unduly cautious, if not afflicted with hypochondria. In our distress, important distinctions will be lost.

Connecticut has just purchased an entire warehouse of what are called personal protective equipment (PPEs) to protect medical workers from Coronavirus, from Chinese Communists who were principally responsible for transporting Coronavirus from Wuhan to Western Europe. No medical gear has yet been found to protect medical workers from politicians.

If China were Big Pharma some ranter on the left by now would have accused Chinese banking magnates of producing a plague so that they might sell medical gowns and facemasks to credulous Nutmeggers in Connecticut. Shrewd Yankees in Connecticut were called Nutmeggers because they used to put wooden nutmegs in with their produce to gain extra coin from their purchasers. Clever Yankees!

Time is a stream, and no one steps in the same stream twice. Things change. We used to be able to depend on our politicians to steer us in the direction of beneficial change. We are just now emerging – one prays -- from the very first intentionally caused national recession in U.S. history.

When the Coronavirus plague has subsided, the question to which we should demand an honest and unambiguous – i.e. non-political -- answer is this: Have our politicians, assisted by medical “experts” and data-manipulators, been selling us a load of wooden nutmegs?

Don Pesci is Vernon-based columnist.

Automatic hand sanitizer

Robert P. Alvarez: We must protect the 2020 election

States’ Electoral College votes

Via OtherWords.org

First, it was a public health crisis. Now, it’s decimating the economy. And for it’s next trick, the coronavirus is threatening to undermine the 2020 election.

Unless, that is, Congress steps in to ensure we can vote by mail.

If you’re curious what the worst case scenario is, look no further than Wisconsin, where a gerrymandered GOP legislature forced voters to the polls over the orders of the Democratic governor — and against the advice of public health officials.

Wisconsin Republicans not only declined to send every voter an absentee ballot. They also appealed — successfully — to the conservative-majority U.S. Supreme Court to prevent voters who received their ballot late (through no fault of their own) from having their votes counted.

It was a transparent ploy by Wisconsin Republicans to support a conservative incumbent on the state Supreme Court by suppressing the vote. It failed — his liberal-leaning challenger won — but they struck a huge blow to voting rights in the process.

Fallout from the coronavirus exposed structural weaknesses in everything from our health care and education systems to market supply chains and labor rights. It also made painfully obvious the fragility of our electoral process.

Unfortunately, states have received little help from Congress in shoring up their elections. Just $400 million of the $2.2 trillion stimulus bill was earmarked for helping states cover new elections-related expenses stemming from the pandemic.

When it comes to providing the financial support necessary to ensure our elections are safe, accessible, fair, and secure, the last coronavirus response bill was a dereliction of duty.

Will it be safe to gather in large numbers by November? And even if it is, will voters feel comfortable standing in line, for up to six hours in some cases (thanks to GOP poll closures, but that’s another story), next to strangers?

If not, it’s fair to assume some voters will elect not to vote due to safety concerns. And that should undermine public confidence in the outcome.

The obvious solution is expanding voting by mail.

Unfortunately, Donald Trump is fiercely opposed to this. “They had things, levels of voting, that if you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again,” he said.

Let that sink in. The president — who himself voted by mail — openly views the right to vote as a threat to his presidency and party.

Americans shouldn’t have to choose between their health and their right to vote. In the midst of this pandemic, states with overly cumbersome processes for absentee voting are complicit in voter suppression. Period.

To fix this, we need to ensure no-excuse absentee voting in the next coronavirus bill — and that’s the bare minimum. Beyond that, we also need pre-paid postage for mail-in ballots and an extended early in-person voting period.

We need accessible, in-person polling places with public safety standards that are up to snuff. That means election workers must know they’re safe, and must have access to personal protective equipment.

We also need to develop and bolster online voter registration systems, and run public information campaigns giving voters localized, up-to-date voting guidelines.

To complete this nationwide, we’re looking at a $2 billion price tag. That’s just 0.1 percent of the $2 trillion package Congress already passed — and if it ensures our democracy doesn’t die in this pandemic, it’s worth every penny.

Robert P. Alvarez is a media relations associate at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he writes about criminal justice reform and voting rights.

Robert P. Alvarez: Don't let pandemic ravage the November election, too

The Balsams, a fancy resort hotel in Dixville Notch, N.H., in the White Mountains, and the site of the "midnight vote" that makes it the first place to vote in U.S. primary and general elections in every election year.

A ballot from the 1936 elections in Nazi Germany — nice and simple!

Via OtherWords.org

First, it was a public-health crisis. Now, it’s ravaging the economy. And for it’s next trick, the coronavirus is threatening to undermine the 2020 election.

Unless, that is, Congress steps in to ensure we can vote by mail.

If you’re curious what the worst case scenario is, look no further than Wisconsin, where a gerrymandered GOP legislature forced voters to the polls over the orders of the Democratic governor — and against the advice of public-health officials.

Wisconsin Republicans not only declined to send every voter an absentee ballot. They also appealed — successfully — to the conservative-majority U.S. Supreme Court to prevent voters who received their ballot late (through no fault of their own) from having their votes counted.

It was a transparent ploy by Wisconsin Republicans to support a conservative incumbent on the state Supreme Court by suppressing the vote. It failed — his liberal-leaning challenger won — but they struck a huge blow to voting rights in the process.

Fallout from the coronavirus exposed structural weaknesses in everything from our health care and education systems to market supply chains and labor rights. It also made painfully obvious the fragility of our electoral process.

Unfortunately, states have received little help from Congress in shoring up their elections. Just $400 million of the $2.2 trillion stimulus bill was earmarked for helping states cover new elections-related expenses stemming from the pandemic.

When it comes to providing the financial support necessary to ensure our elections are safe, accessible, fair, and secure, the last coronavirus response bill was a dereliction of duty.

Will it be safe to gather in large numbers by November? And even if it is, will voters feel comfortable standing in line, for up to six hours in some cases (thanks to GOP poll closures, but that’s another story), next to strangers?

If not, it’s fair to assume some voters will elect not to vote due to safety concerns. And that should undermine public confidence in the outcome.

The obvious solution is expanding voting by mail.

Unfortunately, Donald Trump is fiercely opposed to this. “They had things, levels of voting, that if you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again,” he said.

Let that sink in. The president — who himself voted by mail — openly views the right to vote as a threat to his presidency and party.

Americans shouldn’t have to choose between their health and their right to vote. In the midst of this pandemic, states with overly cumbersome processes for absentee voting are complicit in voter suppression. Period.

To fix this, we need to ensure no-excuse absentee voting in the next coronavirus bill — and that’s the bare minimum. Beyond that, we also need pre-paid postage for mail-in ballots and an extended early in-person voting period.

We need accessible, in-person polling places with public safety standards that are up to snuff. That means election workers must know they’re safe, and must have access to personal protective equipment.

We also need to develop and bolster online voter registration systems, and run public information campaigns giving voters localized, up-to-date voting guidelines.

To complete this nationwide, we’re looking at a $2 billion price tag. That’s just 0.1 percent of the $2 trillion package Congress already passed — and if it ensures our democracy doesn’t die in this pandemic, it’s worth every penny.

Robert P. Alvarez is a media relations associate at the Institute for Policy Studies. He writes about criminal justice reform and voting rights.

Elisabeth Rosenthal/ Emmarie Huetteman: He got tested for COVID-19; then came a flood of medical bills

By March 5, Andrew Cencini, a computer-science professor at Vermont’s Bennington College, had been having bouts of fever, malaise and a bit of difficulty breathing for a couple of weeks. Just before falling ill, he had traveled to New York City, helped with computers at a local prison and gone out on multiple calls as a volunteer firefighter.

So with COVID-19 cases rising across the country, he called his doctor for direction. He was advised to come to the doctor’s group practice, where staff took swabs for flu and other viruses as he sat in his truck. The results came back negative.

In an isolation room, the doctors put Andrew Cencini on an IV drip, did a chest X-ray and took the swabs.

— Photo courtesy of Andrew Cencini

By March 9, he reported to his doctor that he was feeling better but still had some cough and a low-grade fever. Within minutes, he got a call from the heads of a hospital emergency room and infectious-disease department where he lives in upstate New York: He should come right away to the ER for newly available coronavirus testing. Though they offered to send an ambulance, he felt fine and drove the hourlong trip.

In an isolation room, the doctors put him on an IV drip, did a chest X-ray and took the swabs.

Now back at work remotely, he faces a mounting array of bills. His patient responsibility, according to his insurer, is close to $2,000, and he fears there may be more bills to come.

“I was under the assumption that all that would be covered,” said Cencini, who makes $54,000 a year. “I could have chosen not to do all this, and put countless others at risk. But I was trying to do the right thing.”

The new $2 trillion coronavirus aid package allocates well over $100 billion to what Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York called “a Marshall Plan” for hospitals and medical needs.

But no one is doing much to similarly rescue patients from the related financial stress. And they desperately need protection from the kind of bills patients like Cencini are likely to incur in a system that freely charges for every bit of care it dispenses.

On March 18, President Trump signed a law intended to ensure that Americans could be tested for the coronavirus free, whether they have insurance or not. (He had also announced that health insurers have agreed to waive patient copayments for treatment of COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.) But their published policies vary widely and leave countless ways for patients to get stuck.

Although insurers had indeed agreed to cover the full cost of diagnostic coronavirus tests, that may well prove illusory: Cencini’s test was free, but his visit to the ER to get it was not.

As might be expected in a country where the price of a knee X-ray can vary by a factor of well over 10, labs so far are charging between about $51 (the Medicare reimbursement rate) and more than $100 for the test. How much will insurers cover?

Those testing laboratories want to be paid — and now. Last week, the American Clinical Laboratory Association, an industry group, complained that they were being overlooked in the coronavirus package.

“Collectively, these labs have completed over 234,000 tests to date, and nearly quadrupled our daily test capacity over the past week,” Julie Khani, president of the ACLA, said in a statement. “They are still waiting for reimbursement for tests performed. In many cases, labs are receiving specimens with incomplete or no insurance information, and are burdened with absorbing the cost.”

There are few provisions in the relief packages to ensure that patients will be protected from large medical bills related to testing, evaluation or treatment — especially since so much of it is taking place in a financial high-risk setting for patients: the emergency room.

In a study last year, about 1 in 6 visits to an emergency room or stays in a hospital had at least one out-of-network charge, increasing the risk of patients’ receiving surprise medical bills, many demanding payment from patients.

That is in large part because many in-network emergency rooms are staffed by doctors who work for private companies, which are not in the same networks. In a Texas study, more than 30 percent of ER physician services were out-of-network — and most of those services were delivered at in-network hospitals.

The doctor who saw Cencini works with Emergency Care Services of New York, which provides physicians on contract to hospitals and works with some but not all insurers. It is affiliated with TeamHealth, a medical staffing business owned by the private equity firm Blackstone that has come under fire for generating surprise bills.

Some senators had wanted to put a provision in legislation passed in response to the coronavirus to protect patients from surprise out-of-network billing — either a broad clause or one specifically related to coronavirus care. Lobbyists for hospitals, physician staffing firms and air ambulances apparently helped ensure it stayed out of the final version. They played what a person familiar with the negotiations, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, called “the COVID card”: “How could you possibly ask us to deal with surprise billing when we’re trying to battle this pandemic?”

Even without an ER visit, there are perilous billing risks. Not all hospitals and labs are capable of performing the test. And what if my in-network doctor sends my coronavirus test to an out-of-network lab? Before the pandemic, the Kaiser Health News-NPR “Bill of the Month” project produced a feature about Alexa Kasdan, a New Yorker with a head cold, whose throat swab was sent to an out-of-network lab that billed more than $28,000 for testing.

Even patients who do not contract the coronavirus are at a higher risk of incurring a surprise medical bill during the current crisis, when an unrelated health emergency could land you in an unfamiliar, out-of-network hospital because your hospital is too full of COVID-19 patients.

The coronavirus bills passed so far — and those on the table — offer inadequate protection from a system primed to bill patients for all kinds of costs. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, passed last month, says the test and its related charges will be covered with no patient charge only to the extent that they are related to administering the test or evaluating whether a patient needs it.

That leaves hospital billers and coders wide berth. Cencini went to the ER to get a test, as he was instructed to do. When he called to protest his $1,622.52 bill for hospital charges (his insurer’s discounted rate from over $2,500 in the hospital’s billed charges), a patient representative confirmed that the ER visit and other services performed would be “eligible for cost-sharing” (in his case, all of it, since he had not met his deductible).

Last weekend he was notified that the physician charge from Emergency Care Services of New York was $1,166. Though “covered” by his insurance, he owes another $321 for that, bringing his out-of-pocket costs to nearly $2,000.

By the way, his test came back negative.

When he got off the phone with his insurer, his blood was “at the boiling point,” he told us. “My retirement account is tanking and I’m expected to pay for this?”

The coronavirus aid package provides a stimulus payment of $1,200 per person for most adults. Thanks to the billing proclivities of the American health care system, that will not fully offset Cencini’s medical bills.

Elisabeth Rosenthal: erosenthal@kff.org, @rosenthalhealth

Emmarie Huetteman: ehuetteman@kff.org, @emmarieDC

On the Bennington College campus on a dreary day

Jill Richardson: Stay at home and stay angry

Via OtherWords.org

Social distancing is hard, and it’s not fun.

I don’t question that we are doing what is necessary. Until better testing, treatment, and prevention are available, it is. But quarantining us in our homes separates us at a time when we need connection.

And you know what? It’s okay to feel angry about that. It’s important to remember we’re doing this in part because the people at the top screwed up.

Trump fired the pandemic response team two years ago, even though Obama’s people warned them that we needed to work on preparedness for exactly this in 2016. Unsurprisingly, a government simulation exercise just last year found we were not prepared for a pandemic.

Later on, even after the disease had come to the U.S., infectious disease experts in Washington State had to fight the federal government for the right to test for the coronavirus.

It gets worse.

Now we know that North Carolina Sen. Richard Burr was taking the warnings seriously weeks before any real action was taken — and all he did was sell off a bunch of stock, while telling the public everything was fine. Meanwhile, Trump didn’t want a lot of testing, because he wanted to keep the number of confirmed cases low to aid his re-election.

The people we trusted to keep us safe didn’t do that. Now the entire economy’s turned upside down, people are dying, and we’re all cooped up at home.

It sucks. We should be angry.

I’m young enough that I probably don’t have to worry much about the likelihood of a serious case if I get sick. But I’m staying home, because I don’t want to get it and accidentally spread it to someone more vulnerable than myself.

I’m also aware of the sacrifice that many of us are making for the sake of others. Some lost their jobs, while others put themselves at risk working outside the home because they can’t afford not to — or, in the case of health care workers, because they’re badly needed.

Entire families are cooped up together and I’ve heard jokes that divorce lawyers will get plenty of business after this. Parents are posting memes about how much they appreciate teachers now that they are stuck with their kids all day. I’m entirely alone besides a cat.

I worry about the college seniors graduating this year and trying to find a job. What about people prone to anxiety and depression? How much will this exacerbate domestic abuse? What about people in jails, prisons, and detention centers?

Our society is deeply unequal. So while the virus itself doesn’t discriminate, this bigger crisis will hit people unequally. Some don’t have health insurance. Some are undocumented. Some are more susceptible to dying from the disease.

The people in power who screwed up are wealthy enough that they can work from home, maintain their income, and access affordable health care. Others will feel the full brunt of this, not them. It’s not fair.

I’m supportive of doing all we can to prevent the virus’s spread and to protect vulnerable people, but anger at the people whose incompetence put us in this position is justified. We deserve better.

Jill Richardson, a sociologist, is an OtherWords.org columnist.

David Warsh: With economic depression coming on, 'I believe in news'

Police attack demonstrating unemployed workers in Tompkins Park, in New York, in 1874, during the deep depression then.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The European and North American economies are entering a period of depression that already resembles the Great Depression more than any other experience in living memory.

This depression won’t last a decade; perhaps it will last no more than six or nine months. It will not end in a global war, though it certainly has exacerbated international relations. But lock-down policies to cope with the coronavirus pandemic already in place probably insure a couple of quarters that will set records for unemployment, bankruptcies and many more painful deprivations.

Now these policies are about to become the center of a political argument, the most consequential of the Trump presidency — 21st Century equivalent of the Battle of Gettysburg. That’s a strong analogy, I know. But compared to the earlier clashes of the Trump presidency – the Russia investigation, the impeachment trial – the continuing engagement over his handling of the pandemic will eventually deliver a climax worthy of the comparison. It will be radical opportunism vs. the pursuit of knowledge: Between now and Nov. 3, Trump will try to permanently divide the nation. It is not clear which side will win.

First things first. What happened in money markets over the course of the last few days bore little resemblance to the desperate events of September 2008. The coronavirus crisis hasn’t produced a systemic banking panic like the worldwide financial meltdown that threatened then. This time the Federal Reserve System has addressed only a series of alarms in various debt markets in which the underlying concern was about impending business losses. Former Federal Reserve Chairs Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke described the Fed’s actions and their limits in a bracing article March 19 in the Financial Times.

However, the Fed and other policymakers face an even bigger challenge. They must ensure that the economic damage from the pandemic is not long-lasting. Ideally, when the effects of the virus pass, people will go back to work, to school, to the shops, and the economy will return to normal. In that scenario, the recession may be deep, but at least it will have been short.

But that isn’t the only possible scenario: if critical economic relationships are disrupted by months of low activity, the economy may take a very long time to recover. Otherwise healthy businesses might have to shut down due to several months of low revenues. Once they have declared bankruptcy, re-establishing credit and returning to normal operations may not be easy. If a financially strapped firm lays off — or declines to hire — workers, it will lose the experienced employees needed to resume normal business. Or a family temporarily without income might default on its mortgage, losing its home.

On March 16, former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh (no relation of mine) criticized the “2008-style barrages” of Fed measures the day before, including cutting its short-term policy interest rate to near zero. He called for the creation of a Government Backed Credit Facility (GBCF), a huge loan facility, to be administered by 12 regional Federal Reserve banks, backstopped by the Treasury, to lend to companies in danger of going broke who are willing to pledge assets in return for the money.

Meanwhile, Congress publicly debated Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and Treasury Secretary Steven Munchin’s plan to write checks to help individuals get through their hard times. Behind the scenes, the rest of Munchin’s plan: $50 billion for the airlines, $150 billion more for other troubled businesses, and $300 billion for small- business loans.

That was before governors began shutting down their states’ economies with orders of various degrees of severity – Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Texas, California, Illinois and New York.

The backlash began on March 17, when Stat, a widely respected, Boston-based online news organization, published “A Fiasco in the Making?’’, by John P.A. Ioannides, a professor of statistics and epidemiology at Stanford University. As a top expert on statistical sampling, Ioannides complained of the dearth of broad samples of the rate of infection and death. But based on the limited evidence from the one thoroughly studied sample – the 700 passengers of the Diamond Princess cruise ship, of whom seven persons have died – the “kill rate” of Covid-19 might be somewhere between 0.05 percent and 1 percent of those infected, or about the same as regular flu.

If that were determined by better sampling to be the case generally, Ioannides argued, then extreme measures taken could have perverse effects. Or as my friend Lou Fedorkow put it in calling the article to my attention, the United States, having reacted to the 9/11 attacks by going to war in Afghanistan and Iraq, today may be responding to the COVID-19 virus pandemic by going to war with itself.

Also on March 17, the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal, confusing financial-market distress with panic about the economy itself, began a series of editorials, which, in the course of the week, worked their way through to the conviction that the lock-downs were disastrous and needed to be undone. In “Financing an Economic Shutdown, ‘‘ they complained that “Some state and federal leaders [were] shutting down the economy without a plan to finance it while everyone stays home.” They lauded former Governor Warsh’s plan.

The next day, “The Fiscal Stimulus Panic’’ advocated Food Stamps and expanded jobless insurance instead of those checks, which were said to be motivated by a “Keynesian illusion.” On March 19 came “Economic Rout Accelerates’’:

You don’t calm a panic by floating ill-considered trial balloons or chanting “go big” as an illusion of proper and thoughtful action. Markets are panicked in part because they sense that our political leaders are more panicked than the public is.

You calm a panic first by looking like you know what you’re doing. You explain that this is a liquidity problem caused by an extraordinary precaution against a virus that is closing down businesses. The government needs to act to prevent the liquidity panic from becoming a solvency rout that becomes a banking crisis. And it needs to act fast.

By March 20, the editorialists had recognized the likelihood of depression and were “Rethinking the Coronavirus Shutdown’’.

If this government-ordered shutdown continues for much more than another week or two, the human cost of job losses and bankruptcies will exceed what most Americans imagine. This won’t be popular to read in some quarters, but federal and state officials need to start adjusting their anti-virus strategy now to avoid an economic recession that will dwarf the harm from 2008-2009.

And on March 21, in “Leaderless on the Economy,’’ repeating its mantra, “Government needs to address the liquidity crisis it has created for private business, or this will soon become a solvency panic as companies default on debt and fail, which will turn into a banking crisis.” Criticizing “The Extreme State Lockdowns’’ in New York and California as “unsustainable,” they concluded,

Americans may simply decide to ignore the orders after a time. Absent a more thorough explanation of costs and benefits, we doubt these extreme measures will be sustainable for long as the public begins to chafe at the limits and sees the economic consequences.

As usual, it was left to WSJ columnist Holman Jenkins Jr., the sharpest member of the Editorial Board, to draw out the implications. On March 21, in “What Victory Looks Like in the Coronavirus War,’’ he argued for taking what had been the British approach: isolate those who test positive for the disease and encourage everybody else to take care with their sneezes, hand-washing, etc. He continued,

Inconveniently for my argument, the U.K., a pioneer of such thinking, is now shifting to an accept-a-depression-and-wait-for-a-vaccine approach. The medical experts and their priorities are hard to resist. Resisting their wisdom doesn’t come naturally in such a situation.

Happily, I have confidence in the American people to let their leaders know when the mandatory shutdowns no longer are doing it for them. Strange to say, I have confidence in our political class to sense where the social fulcrum lies. A reader emails that Donald Trump could declare victory at the end of 15 days, claim the blow on the health-care system has been cushioned, and urge Americans, super-cautiously, to resume normal life. This idea sounds better than waiting for spontaneous mass defections from the ambitions of the epidemiologists to undermine the authority of the government.

Meanwhile, Bret Stephens, who left the WSJ Editorial Board in 2017 for a column in The New York Times because he so objected to the former’s embrace of Trump, made a similar point March 22 in “It’s Dangerous to be Ruled by Fear’’:

Sooner or later, people will figure out that it is not sustainable to keep tens of millions of people in lockdown; or use population-wide edicts rather than measures designed to protect the most vulnerable; or expect the federal government to keep a $21 trillion economy afloat; or throw millions of people out of work and ask them to subsist on a $1,200 check.

And as if to put a human face on the opposition to current policy, the news pages of the WSJ, a preserve of traditional news values, discovered and described entrepreneur Elon Musk’s holdout for days against suspending car production in his Fremont, Calif., “The coronavirus panic is dumb,” Musk argues.

How do these policy decisions get made? I don’t know a better answer – a glimpse of an answer – than “The Humanitarian Revolution” chapter in Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Viking Penguin, 2012). The origins of today’s policy of lockdown is more a question of culture evolving than the existence of an epidemiological “deep state.” Obviously the costs and benefits of various approaches to managing the epidemic should be regularly examined, Bayesian-fashion – without ridicule. As for the covid-19 pandemic, I come down on the side of the Rev. Thomas Bayes (1701-1761), who argued more than 250 years ago that, statistically, we learn from experience; specifically, that by updating our initial beliefs with carefully obtained new information, we improve our beliefs about the prospects of whatever we undertake to know. In other words, I believe in news.

So get ready for a ferocious debate about the measures adopted. It seems certain to grow in bitterness and carry on down to Election Day. The situation is encapsulated in this 40-second viral clip from a presidential news conference. Watch it twice, the first time for epidemiologist Anthony Fauci’s reaction to what the president is saying, the second time to see the look Fauci eventually receives from Trump. That was the moment in which the climactic battle of Trump’s presidency began.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Arthur Waldron: COVID-19 probably originated in a Wuhan lab

Part of the vast city of Wuhan

PHILADELPHIA

Early this just-finished winter, physicians in Wuhan, China, became aware of cases of a new flu-like illness. It was related, as a so-called coronavirus, to the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome virus (SARS). SARS wrought havoc in China in 2003, causing some 8,000 infections, along with a mortality rate of at least 10 percent. It brought martial law to Beijing and elsewhere in China.

The new pathogen, which we’re now getting used to calling COVID-19, is also a coronavirus, thought to be endemic in bats, and transmitted to humans by an as yet unknown pathway (possibly the pangolin, a lovable denizen of the tropics).

The holocaust in China since December has now done previously unimaginable harm, with tens of thousands or more infected in the nation and a death rate comparable to SARS, bringing much of China to a panicky halt. And now there are hundreds of thousands – or more – cases in the world, and many thousands of deaths as the pandemic rolls on.

All of the noble doctors and other health providers who perished, such as Dr. Li Wenliang, who left a child and an infected pregnant wife -- and there were many more -- fearlessly confronted COVID-19, but without one crucial piece of information: namely, how it spread. It was known that the virus could jump from some animals to other animals, and from one person to another, but how exactly did it get from other animals to humans?

Throughout southern China exist hundreds of technically illegal markets, often huge, such as the one in Wuhan, holding wild species, some endangered, that are not legal to sell or eat. But they are consumed anyway. Bats are sold there, and bats are known to harbor the new coronavirus, as do many other unfortunate creatures. A mainstream story developed saying that the viruses jumped from the bats to another species, and thence to people.

The search is on for this creature. However, it probably does not exist and the whole theory about the virus is probably wrong. The simplest explanation for the epidemic is that somehow a form of the new coronavirus, which normally cannot infect human beings, either appeared through natural mutation and spread, or was engineered in a specially protected research facility for just such perilous work.

The epicenter of the infection is in Wuhan, Hubei, China’s great riverine transportation hub, with a population of 11 million — much bigger than New York. A vast wild animal market has long been there. But no way exists to demonstrate that this “wet market” is point zero. Quite the opposite, for a significant number of infections cannot be traced to the animals there.

Also in Wuhan is the Wuhan Institute of Virology and another laboratory configured specifically for such highly dangerous experiments as modifying bacteria and viruses so that they can yield vaccine or be used as biological weapons. These were built over 10 years with French assistance. That French plan for a research partnership fell through but the state-of-the art, level 4 (the highest-security) laboratory remained, and was put to use.

Now we approach the crux of the matter.

The findings of a long-term study, sponsored by the University of North Carolina, were published in Nature in August 2015. Nature is the most authoritative and trusted regular journal publishing new scientific results. Sixteen international experts participated in the study, including Dr. Zheng-li Shi and Dr. Xing-yi Ge, both of the level four laboratory in Wuhan. Here, with some explanation is what they reported:

“. . . We generated and characterized a chimeric virus expressing the spike of bat coronavirus in a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV [coronavirus] backbone. The [result] could] efficiently use multiple orthologs [genetically unrelated variants] of the human SARS receptor, angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE ) to enter, reproduce efficiently in primary human airways cells, and achieve in vitro titers [sufficiently lethal concentrates] equivalent to epidemic strains of SARS-CoV.”

In other words, using one component of the new coronavirus and another one of SARS, one could create a new virus having a deadliness close to that of SARS and able to cross the species barrier, be fruitful and multiply, killing large numbers of victims, particularly elderly people.

From a virological standpoint this was an important breakthrough in understanding how viruses can propagate into new species. The doctors in the experiments, however, were shocked by its medical implications: Neither monoclonal antibodies nor vaccines killed it. The new virus, which was replicated and christened SHC104, [demonstrated] “robust viral replication, in vitro [lab-ware] and in vivo” [living creatures].

“Our work” the authors noted fearfully, “suggests a potential risk of SARS-CoV emergence from viruses now circulating in bat populations.” It seems likely to me that the new coronavirus did emerge in some such way, as a result of error at the Chinese P4 laboratory. Perhaps the search was for a vaccine. Less likely is that it was the result of research to create a biological weapon, for though such research is widespread worldwide (restarted in 1969 in the United States), the coronavirus is, in one sense, mild: Some people die, but most recover. It is not anthrax.

In any event, I think that an innocent but catastrophic mistake at the Wuhan P4 lab is now bringing something like Götterdämmerung to China.

If components of the new bat virus were connected in the laboratory to those of the known SARS virus, the result was a “virus that could attach functionally to the human SARS receptor, angiotensin converter enzyme II, with which it had similarities but no kinship (“orthologs”). The species barrier was thus crossed with a laboratory-created virus that could copy itself, reproduce in human airways, e.g., the lungs, and produce in glass laboratory equipment the equivalent of titers (amounts of liquid sufficiently concentrated) to achieve the strength of epidemic strains of SARS.

One intriguing piece of evidence appeared very briefly in the Chinese press.

A Southeast Asian editor wrote me:

“I also found this Caixin {Chinese media company} piece interesting. Especially the following paragraph:

{Prof. Richard Ebright, the laboratory director at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology and a professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Rutgers University} “cited the example of the SARS coronavirus, which first entered the human population as a natural incident in 2002, before spiking for a second, third, and fourth time in 2003 as a result of laboratory accidents.”

This article disappeared almost instantly but its contents have been circulating in Southeast Asia.

It indicates that laboratory mishaps were involved in SARS. So the same possibility cannot be ruled out now. The original article has been expunged in China, including from the Caixin archives.

Since then no more technical or scientific evidence has appeared. So we wait for an explanation from the Chinese government.

In China, the fabric of the society is tearing; its foundations and structures are bending and stooping under the lash of a deathly microorganism, apparently made by humans and somehow released, the effects of which few conceived or expected. Now populations of tens of millions around the world face and may well pay the ultimate price. The all-knowing Chinese Communist Party looks absurd and corrupt. In Wuhan supplies are scarce and crematories have worked 24/7 to dispose of the dead. The self-sacrificing medical profession, however, has little idea of where to turn for a cure.

We are in the midst of a global tragedy. Officials of the despotic Chinese government, which designed and built the Wuhan facility, seem ignorant about what they set in motion, while the biologists, with perhaps some exceptions, will recoil, as will subsequent generations, with what they have wrought.

Arthur Waldron is Lauder Professor of International Relations at the University of Pennsylvania and an historian of China. He’s also a longtime friend and colleague of Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor.

Llewellyn King: Now that the pandemic has shut us in what will we do with our time?

Centreville Mill, on the Pawtuxet River, in West Warwick, R.I. Llewellyn King lives in a converted mill on the same river in West Warwick.

For more than a decade, I’ve been writing about the isolated, the lonely, the abandoned: Those who feel that the world has no place for them. Now all of us will know something of their isolation and, in the case of people who live on their own, loneliness.

Those I’ve been writing about are the luckless hundreds of thousands in the United States – millions around world -- who suffer from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, now known as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME). They are sentenced to live separately by their illness and its debilitating fatigue. They are a kind of living dead. Now I have a glimmer, no more to be sure, of how it must be every day for these sufferers

What will it be like for the rest of us in two weeks when we’ve exhausted the pleasures of home life and yearn to see our friends, go to a restaurant, a play or a concert? Just to live normally?

I’ve always tried to console myself with what I call “adventure therapy.” Like most pop psychology it isn’t very profound, but it does help. Will it help now? I have no idea.

Anyway, the therapy is that you try to find the adventure in any situation you’re in, which can include some hairy ones, like facing surgery. (Who will you meet? What’s all the equipment? How will they perform the surgery? Do the doctors like doctoring? What kind of life do the nurses live?)

In my own home -- mercifully which I share with my ever-cheerful wife -- I wonder where the adventure lies in this crisis.

First, I know I won’t write the Great American Novel or any work of fiction. I won’t write my life story, as I’m constantly advised to do. My ego is robust, but I’m not sure it’s robust enough for that.

Oscar Wilde worried about “third-rate litterateurs” picking over the lives of dead writers. Of course, it seems to me some lives are lived with an eye to posterity.

I’m always amazed at people who in the middle of great trauma or great events have time to sit down and write what they think and feel. I’m glad they do, but I don’t think we’re entitled. The world loves Shakespeare’s works and knows little about him.

We know too much about people of minor achievement whom we call celebrities. We watch them and their petty lives with the attention of a fakir watching his snake. Yeah, I’m no better. I want to know what’s to become of Meghan and Harry, where will Lindsay Lohan settle and, only somewhat less trivially, what are the late-night comedians doing with their spare time now that we learn that they need huge staffs to be funny?

I do think that we need a record of our times, often informed by memoirs. Unfortunately, and inexcusably, when the Trump era is behind us, we’ll know too little about what went on in the inner councils of the White House. President Trump has shown near contempt for the Presidential Records Act, inspired by the fall of President Richard Nixon. Trump writes little and destroys much that it written, we’re told.

One has always dreamed of a time when there was enough leisure to read, maybe plow through Tolstoy, give Proust another go, or try to understand Chinese literature. But I think that won’t happen. I’ll read the same kind of books I always read: biographies and crime stories. Most likely I’ll read a bit more, curse television a bit more, and squander my time watching and reading the news about COVID-19.

As I struggle to avoid the temptations of the refrigerator and that reproving word processor (It whispers, “Write a book.”), I’ll wonder about those who existed before this pandemic in a long, dark tunnel of isolation without hope of light at the end: Those who can hardly hope to break out one day into what Winston Churchill called the “sunlit uplands.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.