Debby Waldman: Driving to Vermont to arrange to die

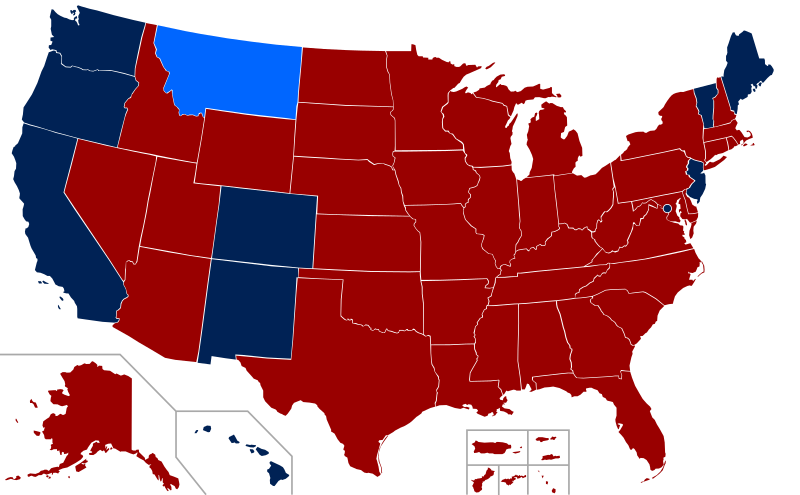

Legality of assisted suicide in the U.S. It’s clearly legal in dark blue states, legal in light blue Montana under a court order and illegal in red states.

Text From Kaiser Family Health News

In the 18 months after Francine Milano was diagnosed with a recurrence of the ovarian cancer she thought that she’d beaten 20 years ago, she traveled twice from her home in Pennsylvania to Vermont. She went not to ski, hike, or leaf-peep, but to arrange to die.

“I really wanted to take control over how I left this world,” said the 61-year-old who lives in Lancaster. “I decided that this was an option for me.”

Dying with medical assistance wasn’t an option when Milano learned in early 2023 that her disease was incurable. At that point, she would have had to travel to Switzerland — or live in the District of Columbia or one of the 10 states where medical aid in dying was legal.

But Vermont lifted its residency requirement in May 2023, followed by Oregon two months later. (Montana effectively allows aid in dying through a 2009 court decision, but that ruling doesn’t spell out rules around residency. And though New York and California recently considered legislation that would allow out-of-staters to secure aid in dying, neither provision passed.)

Despite the limited options and the challenges — such as finding doctors in a new state, figuring out where to die, and traveling when too sick to walk to the next room, let alone climb into a car — dozens have made the trek to the two states that have opened their doors to terminally ill nonresidents seeking aid in dying.

At least 26 people have traveled to Vermont to die, representing nearly 25% of the reported assisted deaths in the state from May 2023 through this June, according to the Vermont Department of Health. In Oregon, 23 out-of-state residents died using medical assistance in 2023, just over 6% of the state total, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

Oncologist Charles Blanke, whose clinic in Portland is devoted to end-of-life care, said he thinks that Oregon’s total is likely an undercount and he expects the numbers to grow. Over the past year, he said, he’s seen two to four out-of-state patients a week — about one-quarter of his practice — and fielded calls from across the U.S., including New York, the Carolinas, Florida and “tons from Texas.” But just because patients are willing to travel doesn’t mean it’s easy or that they get their desired outcome.

“The law is pretty strict about what has to be done,” Blanke said.

As in other states that allow what some call physician-assisted death or assisted suicide, Oregon and Vermont require patients to be assessed by two doctors. Patients must have less than six months to live, be mentally and cognitively sound, and be physically able to ingest the drugs to end their lives. Charts and records must be reviewed in the state; neglecting to do so constitutes practicing medicine out of state, which violates medical-licensing requirements. For the same reason, the patients must be in the state for the initial exam, when they request the drugs, and when they ingest them.

State legislatures impose those restrictions as safeguards — to balance the rights of patients seeking aid in dying with a legislative imperative not to pass laws that are harmful to anyone, said Peg Sandeen, CEO of the group Death With Dignity. Like many aid-in-dying advocates, however, she said such rules create undue burdens for people who are already suffering.

Diana Barnard, a Vermont palliative-care physician, said some patients cannot even come for their appointments. “They end up being sick or not feeling like traveling, so there’s rescheduling involved,” she said. “It’s asking people to use a significant part of their energy to come here when they really deserve to have the option closer to home.”

Those opposed to aid in dying include religious groups that say taking a life is immoral, and medical practitioners who argue their job is to make people more comfortable at the end of life, not to end the life itself.

Anthropologist Anita Hannig, who interviewed dozens of terminally ill patients while researching her 2022 book, The Day I Die: The Untold Story of Assisted Dying in America, said she doesn’t expect federal legislation to settle the issue anytime soon. As the U.S. Supreme Court did with abortion in 2022, it ruled assisted dying to be a states’ rights issue in 1997.

During the 2023-24 legislative sessions, 19 states (including Milano’s home state of Pennsylvania) considered aid-in-dying legislation, according to the advocacy group Compassion & Choices. Delaware was the sole state to pass it, but the governor has yet to act on it.

Sandeen said that many states initially pass restrictive laws — requiring 21-day wait times and psychiatric evaluations, for instance — only to eventually repeal provisions that prove unduly onerous. That makes her optimistic that more states will eventually follow Vermont and Oregon, she said.

Milano would have preferred to travel to neighboring New Jersey, where aid in dying has been legal since 2019, but its residency requirement made that a nonstarter. And though Oregon has more providers than the largely rural state of Vermont, Milano opted for the nine-hour car ride to Burlington because it was less physically and financially draining than a cross-country trip.

The logistics were key because Milano knew she’d have to return. When she traveled to Vermont in May 2023 with her husband and her brother, she wasn’t near death. She figured that the next time she was in Vermont, it would be to request the medication. Then she’d have to wait 15 days to receive it.

The waiting period is standard to ensure that a person has what Barnard calls “thoughtful time to contemplate the decision,” although she said most have done that long before. Some states have shortened the period or, like Oregon, have a waiver option.

That waiting period can be hard on patients, on top of being away from their health-care team, home, and family. Blanke said he has seen as many as 25 relatives attend the death of an Oregon resident, but out-of-staters usually bring only one person. And while finding a place to die can be a problem for Oregonians who are in care homes or hospitals that prohibit aid in dying, it’s especially challenging for nonresidents.

When Oregon lifted its residency requirement, Blanke advertised on Craigslist and used the results to compile a list of short-term accommodations, including Airbnbs, willing to allow patients to die there. Nonprofits in states with aid-in-dying laws also maintain such lists, Sandeen said.

Milano hasn’t gotten to the point where she needs to find a place to take the meds and end her life. In fact, because she had a relatively healthy year after her first trip to Vermont, she let her six-month approval period lapse.

In June, though, she headed back to open another six-month window. This time, she went with a girlfriend who has a camper van. They drove six hours to cross the state border, stopping at a playground and gift shop before sitting in a parking lot where Milano had a Zoom appointment with her doctors rather than driving three more hours to Burlington to meet in person.

“I don’t know if they do GPS tracking or IP address kind of stuff, but I would have been afraid not to be honest,” she said.

That’s not all that scares her. She worries she’ll be too sick to return to Vermont when she is ready to die. And, even if she can get there, she wonders whether she’ll have the courage to take the medication. About one-third of people approved for assisted death don’t follow through, Blanke said. For them, it’s often enough to know they have the meds — the control — to end their lives when they want.

Milano said she is grateful she has that power now while she’s still healthy enough to travel and enjoy life. “I just wish more people had the option,” she said.

In June, Milano headed to Vermont to open a second six-month window to receive medical aid in dying. After a six-hour drive, she crossed the state’s border and opted to Zoom with a doctor rather than drive three more hours to meet in person, as she had done the first time.

Debby Waldman is a Kaiser Family Health Plans journalist.

Related Topics

Chris Powell: 'Bring out your dead'? Nullification hypocrisy

Secobarbital is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs for physician-assisted suicide in the United States.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

What should the legislation now making another appearance in the Connecticut General Assembly be called: "aid in dying" or "assisted suicide"? It depends which side you're on.

"Aid in dying" makes it sound a lot nicer, just as "pro-choice" has become the euphemism for "pro-abortion" or, more fairly, "pro-abortion rights." Meanwhile there is no getting around it: "Suicide" signifies desperation and despair.

The bill would authorize doctors to prescribe fatal doses of medicine to terminally ill people who want to end their lives. They might have various motives -- chronic pain, invalidism, reluctance to become a burden on their families, or severe depression.

The bill's opponents contend that pain almost always can be controlled medically now and that there would be great risk of hustling the afflicted into dying for the convenience of others. The bill's advocates say it contains regulations against that.

This trust in regulations may be a bit naive since government can't always be around when it is needed. Who can forget the "bring out your dead" scene in the movie Monty Python and the Holy Grail? That's where the wheelbarrow master collecting corpses amid a plague declines to accept a frail old man who is being carried out by a young relative while still alive. The wheelbarrow master says, "I can't take him like that. It's against regulations." But a little cajoling by the young relative produces the "aid in dying" necessary to get the old man loaded aboard -- a quick and surreptitious clubbing to the head.

On the other hand, can government be trusted to tell people what they can do with their own lives? Who else's business is it really? How is the "war on drugs" working out?

In his play Julius Caesar Shakespeare inclines to the libertarian side of the issue as the conspirators discuss the risk of failure of their plot to assassinate the emperor and restore the Roman republic.

CASSIUS: I know where I will wear this dagger then;

Cassius from bondage will deliver Cassius.

Therein, you gods, you make the weak most strong.

Therein, you gods, you tyrants do defeat.

Nor stony tower, nor walls of beaten brass,

Nor airless dungeon, nor strong links of iron

Can be retentive to the strength of spirit.

But life, being weary of these worldly bars,

Never lacks power to dismiss itself.

If I know this, know all the world besides,

That part of tyranny that I do bear

I can shake off at pleasure.

CASCA: So can I.

So every bondman in his own hand bears

The power to cancel his captivity.

Good for the Catholic Church in Connecticut for citing the sanctity of life in opposing "aid in dying." But far more lives -- mostly young ones -- are lost or jeopardized every day because of practices and policies that neither the government nor the church bothers to get upset about or even examine.

After all, in the long run we're all terminally ill even as the short run is often one blind spot after another.

xxx

NULLIFICATION CATCHES ON: Republican-leaning states that support an expansive view of Second Amendment rights are considering legislation to nullify federal gun laws, especially now that background-check legislation has a good chance of passing Congress. But somehow this nullification movement seems to have escaped the denunciation it deserves from Connecticut's congressional delegation, all of whose members support stronger federal gun controls.

Could such denunciation be lacking because no one in authority in government in Connecticut has any business criticizing nullification elsewhere? For Democratic-leaning Connecticut long has been engaging in more nullification than any state since the civil rights era of the 1950s and '60s. Connecticut's nullification is aimed against federal immigration law, as the state obstructs federal immigration agents from doing their jobs and issues driver's licenses and other forms of identification to immigration lawbreakers.

The Republican-leaning states are only contemplating nullification. In Connecticut it is aggressive policy.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.