William Morgan: Ruminations on an old postcard from Maine

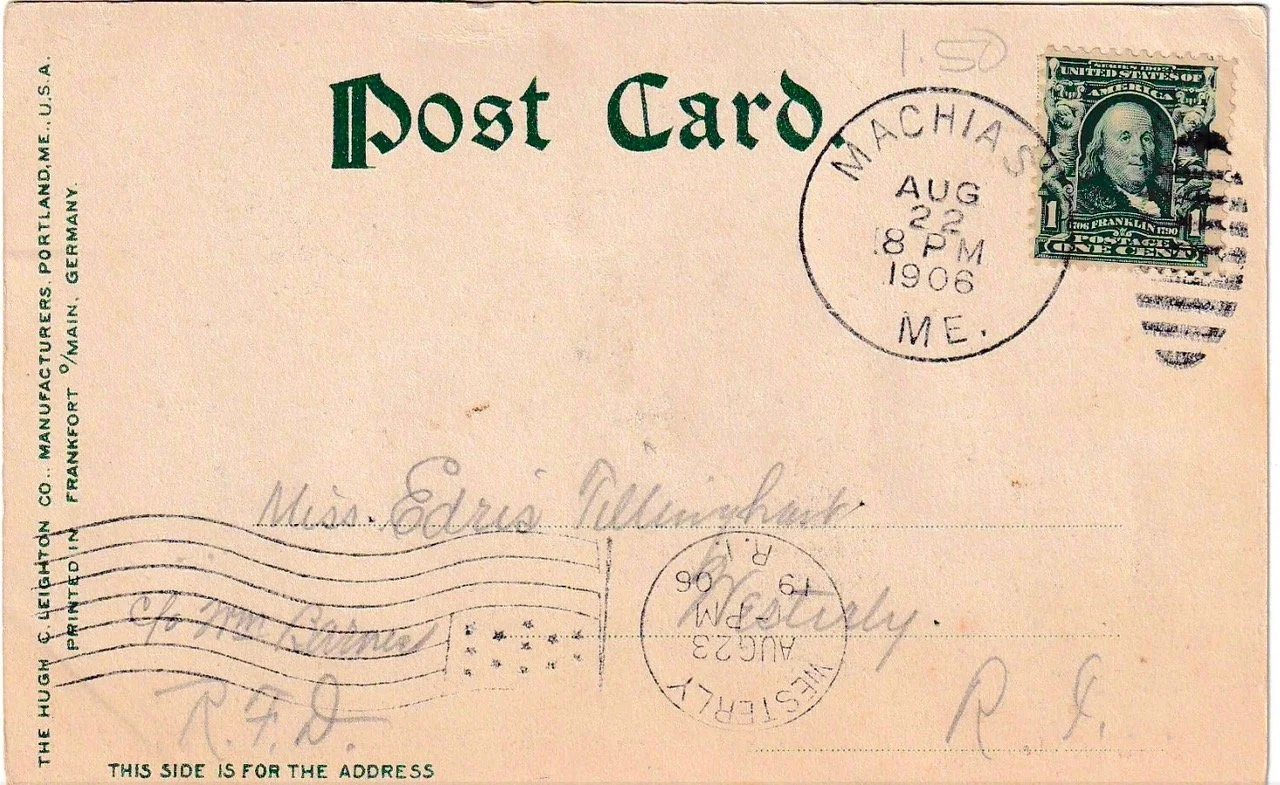

Porter Memorial Library, Machias, Maine. Hand-colored postcard.

Once again, an antique postcard yields memories as well as mysteries. My investment of $1.50 to buy an old card led to down-the-rabbit-hole ruminations.

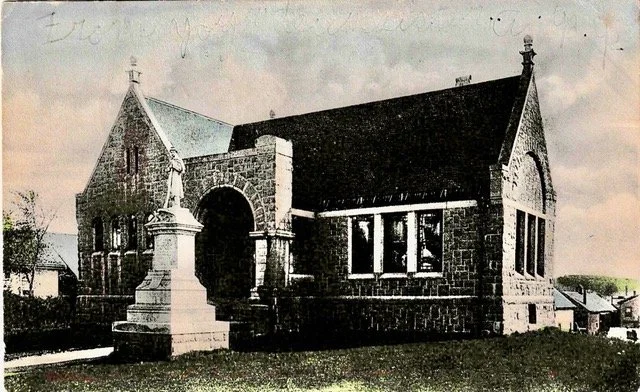

Posted in Machias on Aug. 22, 1906 (Theodore Roosevelt was President); Maine had been a state for only 86 years. The sender, from what we can make out from the pencil scratches on the picture side of the card, was the sister of the recipient, Miss Edris Tillinghast. Tillinghast is a Rhode Island name, but Edris strikes one as one of those late Victorian family names, yet it is well enough known in Wales. Was Miss Edris visiting in Westerly? (Her address is in care of “Wm. Barnes, RFD” (Rural Free Delivery) – her family rusticating on a farm, perhaps)? Or was the sister traveling in far Downeast Maine?

Post card from Hugh C. Leighton Co., Portland, but printed in Germany

The Tillinghast sisters and their undocumented peregrinations may had faded into the mists of time, but the library building in the Washington County seat has remained pretty much unchanged. Chicago businessman and Machias native Henry Holmes Porter gave the money to erect the library in memory of his father, Rufus King Porter, in 1891.

The architect of the Porter Library was George Clough, who hailed from Blue Hill, Maine, and was a successful practitioner in Boston. He designed the Suffolk County Courthouse, on Pemberton Square, Boston, and he was that city’s first City Architect, a position to which he was elected in 1876 and served for seven years. He also designed the public libraries for the Maine towns of Rockland, Bucksport and Vinalhaven.

Postcard of Buck Memorial Library, Bucksport.

Clough’s inspiration for Machias was the Romanesque Revival-style libraries of Henry Hobson Richardson in such suburban Boston towns as Woburn, North Easton and Quincy. Richardson was best known as the architect of Trinity Church at Copley Square in Boston, but his small-town libraries are among his most satisfying works. Clough was one of many New England library builders who borrowed from the Richardsonian formula of monumental reading room, wing for the stacks and ceremonial civic entrance.

Crane Memorial Library, by Henry Hobson Richardson, in Quincy, Mass.

-- Photo by William Morgan

Providence-based writer and photographer William Morgan is the author of a number of books on New England architecture, including A Simpler Way of Life: Farmhouses of New York and New England and Monadnock Summer: The Architectural Legacy of Dublin, New Hampshire.

Times past on Block Island

“Gathering Seaweed (watercolor), in the show “Times Past: New Works by William Talmadge Hall,’’ at the Jessie Edwards Gallery, Block Island, through July 2.

He writes: “Seaweed from the beaches on Block Island was gathered as fertilizer and for food. The rule on Block Island in the 1800’s was that access to all beaches was protected for islanders to gather whatever they could find. This included seaweed, fish, salvage from shipwrecks, heating fuel, such as driftwood, and virtually anything else that would help them survive.’’

{Editor’s note: Seaweed aquaculture has been expanding at a good clip in New England in the past few years. Seaweed has many uses and growing it removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.}

The gallery says:

The show “displays the artist’s love of Block Island and history. These works are personal for Hall, a third-generation islander, and encompass a past he hopes that people think about as he immortalizes the rich and fabulous, and now too-often forgotten, history of the island’s people, land and sea in his beautiful watercolors.’’

“Fisherman’s Corner-Old Harbor Block Island’’

Mr. Hall explains:

“Once thick with fishing shacks, the west corner of Old Harbor was the domain of the Block Island fishing fleet. When the steamers on the Fall River Line docked on the east side of this harbor of refuge, the passengers from New York City, Providence, Boston and elsewhere in the region were delivered into a bustling port. But the hurricane of 1938 devastated this fleet; 80 percent of it was destroyed in a few hours. In its heyday, these docks landed enough fresh fish to meet a substantial part of the demands of urban centers in southern New England as well as of the summer resort season.’’

‘‘Victorian Swim Party” (1889)

“During the late Victorian era, which came to be called ‘The Gilded Age,’ Block Island became know as a tourist venue without the social restrictions imposed by, say, Newport high society. Large luxurious hotels offered a more open attitude to anyone, no matter who they were or where their money came from

“The beautiful and romantic scenery and relatively remote location encouraged discreet pleasure and relaxation.

“This painting evokes a slackening of Victorian dress codes and the pure pleasure

of being alive.’’

Will Morgan: A mystery photo and missing memory

Half a dozen years ago, our current president published a book about his son’s death from glioblastoma. Titled Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose, started with Beau Biden’s plea to his father not to let grief overcome him. (The loss of the Delaware senator’s wife and daughter in a car accident in 1972 almost derailed Biden’s life, including his political career.)

I found an autographed copy of the book, simply inscribed “Joe Biden,’’ in Savers in Boston’s West Roxbury for $4.49. The forgotten best seller did, nevertheless, offer a treasure, the mystery photo above.

There are almost no clues as to the identity of this young girl and, presumably, her younger brother. It’s printed on Kodak Xtralife II paper, but who uses prints in this age of computers and online libraries? The buildings look recent – faux Georgian – although the cobblestone street could be European.

Looking at the lass’s auburn hair and complexion, we could guess that these children are Irish.

There’s a story here, at least in our imaginations. But, promise me, Dad, that you will date your photos and tell us why images like this represent a memory worth keeping.

An architectural and photo historian, William Morgan is a frequent contributor to New England Diary. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published in October.

Grandeur or at least mystery at Good Fortune

— Photo and text by William Morgan

At a time when most public art is too realistic, too political, and just too awful, it can be a pleasure to stumble upon some unplanned artistic achievement– art in spite of itself.

This urinal in Good Fortune, the giant warehouse of Asian food in the Elmwood section of Providence, offers humor, dignity, and an appropriate aura of mystery befitting an intriguing work of art.

This plumbing fixture is broken, but the sign, “Operation Suspended,’’ hints at grander exploits, such as the cancellation of a moon shot or an aborted Navy Seals raid.

Set off by faux marble and black poly-something-or-other, the flushing mechanism takes on the look of a sleek, abstract chromium sculpture – a tribute to American industrialization, perhaps. A dismembered torso, or perhaps a tuxedo on a coat hanger, lurks beneath the shiny, elegant, mink-coat-black drape.

High fashion or a postponed plumbing repair?

William Morgan is a Providence-based writer and architectural historian. He holds a Ph.D. in American Art from the Bidens’ alma mater, the University of Delaware. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published this fall.

#art #Providence

Existential confusion

Inside Greg’s Famous Seafood, in Fairhaven, Mass.

— Photo by William Morgan

William Morgan: A medical firm’s lost design opportunity in a very dramatic spot

When can a substandard commercial building be transformed into good architecture? Can a despised icon of second-rate design become a beloved object? More specifically, can the ugly behemoth of University Orthopedics, in East Providence, R.I., overcome the stigma of being just another spec medical box?

University Orthopedics, 1 Kettle Point, East Providence, N/E/M/D Architects.

Photo by William Morgan

Kettle Point, which is also the site of a development of the kind of suburban housing seen near urban interstates everywhere, is a gorgeous promontory with unparalleled views of the Providence skyline, a working waterfront and down Narragansett Bay. If this site were not in the perceived ugly step-sister of East Providence, it would have been one of the most desirable pieces of land in the state. One thinks of what will happen to the neighboring Metacomet Golf Club course, glorious open land with tremendous potential: It will turn into the all-too-familiar faux-Colonial tackiness on a sea of asphalt.

Kettle Point housing development.

— Photo by Will Morgan

On the positive side, University Orthopedics is affiliated with Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School and so is one of the parts of Providence’s growing importance as a medical center. And the Kettle Point location offers expansive and maybe healing views of water, trees and skyline. This giant infusion of sunlight and a panorama of nature must surely contribute to the wellness of the patients and the happiness of the staff.

Providence harbor and downtown skyline from Kettle Point.

— Photo by William Morgan

The ugly duckling becomes a swan when a loved one needs treatment for osteoporosis or a broken limb. Then the state-of-the-art facilities and the staff’s training seem more important than aesthetics. But do they need to be mutually exclusive? What if the medical group that commissioned 1 Kettle Point had hired someone besides a value-engineering-minded developer? At the very least, a location this visible demanded a better design than a clunky real-estate container wrapped in cheap materials, one that looks like every other new medical office block from Boise to Little Rock.

Does this signage or the Home Depot-orange cladding symbolize quality medicine and research?

— Photo by William Morgan

A sensitive architect might have at least given 1 Kettle Point a more distinctive skyline. (Please do not whine that a good architect costs too much, as a really smart designer might have even given University Orthopedics a lot more for less.) And given such an environmentally sensitive site, a landscape architect should have been consulted, and maybe allowed to integrate this hulk into its prime surroundings.

Alas, the response in our high-quality (for those who can access it) but often unobtainable, fragmented and even chaotic American health-care system to such concerns is always one of money. What a building looks like seems minor compared to the medicine it delivers. But why not heal the entire patient, while at the same time supporting a quality building that could have been a great advertisement for the practice, for Brown, for Rhode Island?

The handsome lights on the stair compliment the undoubtedly unintentional industrial aesthetic of the metal railings.

— Photo by Will Morgan

Hospital needs, admittedly, dictate their forms. Think of all the university-affiliated and other medical centers that keep spreading across America, with new wings and additions, often in disparate styles. Yet, a handsome example that exists within the jumble of buildings that comprise the main campus of the august Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, is the handsome neoclassical original building, designed by Charles Bulfinch. In erecting their signature structure, the hospital trustees chose the architect of both the Massachusetts State House and the U.S. Capitol.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Charles Bulfinch, architect, 1818-23. Wikimedia Commons.

My favorite example of a successful hospital that is also a work of architecture is a tuberculosis sanatorium in rural Finland, designed in 1929 by a then-young Alvar Aalto. Built with limited resources, the sanatorium launched Aalto’s career, but it also became one of the noblest landmarks of modern architecture. The revolutionary aspects of the design were dictated by the treatment of TB, which emphasized abundant sunlight and fresh air. Aalto fashioned draft-less windows and splash-less sinks, along with bright colors and inexpensive furniture that is still being manufactured.

Tuberculosis sanatorium, Paimio, Finland, 1929-33.

— Photo by the Alvar Aalto Foundation.

Why should what University Orthopedics looks like, and how it contributes to or detracts from its environment, be any less important than the layout of its labs and operating rooms? This medical group, presumably, would not accept low professional standards of medicine. So, it is unfortunate that, in the quest for medical integrity, University Orthopedics’ patronage did not aspire to high standards of architectural design

William Morgan has taught the history of modern architecture at several colleges, including Princeton and Roger Williams Universities, and has written extensively on Finnish architecture.

William Morgan: First Communion

A bit of kitsch in the town where Henry David Thoreau made Walden Pond world-famous.

Despite its trite name, Thoreauly Antiques, on Walden Street, in Concord, Mass., remains a fertile hunting ground for old photos that suggests many a tale of everyday New Englanders.

Maybe with computers and their sophisticated photo programs, a lot of images are being stored for future generations – knowing that all my floppy disks are unreadable, perhaps not. Maybe the shoebox of treasured images was just as good a storage system.

For 50 cents I was able to recapture the day of this young woman's first confirmation three quarters of a century ago. The Regal Magic-Eye Enlargement was made in Quincy. The girl's name and other information may have been in the scrapbook in which this memory was pasted. But one does not want to contemplate the demise of the scrapbook or the journey of this snapshot of one of life's landmark moments to a junk shop.

May 19, 1942 was a Tuesday, so we can guess the confirmation took place on May 17. On that day, German and Soviet forces were battling for Kharkov, American submarines were chasing their Japanese counterparts following the Battle of the Coral Sea, while in the Atlantic U-boats sunk almost a dozen Allied ships.

But back in Boston, the day was sunny and full of hope.

William Morgan is a Providence-based writer and architectural historian. He has taught the history of photography, and co-authored the book Bucks County with the late RISD photography professor Aaron Siskind.