‘Construct an ending’

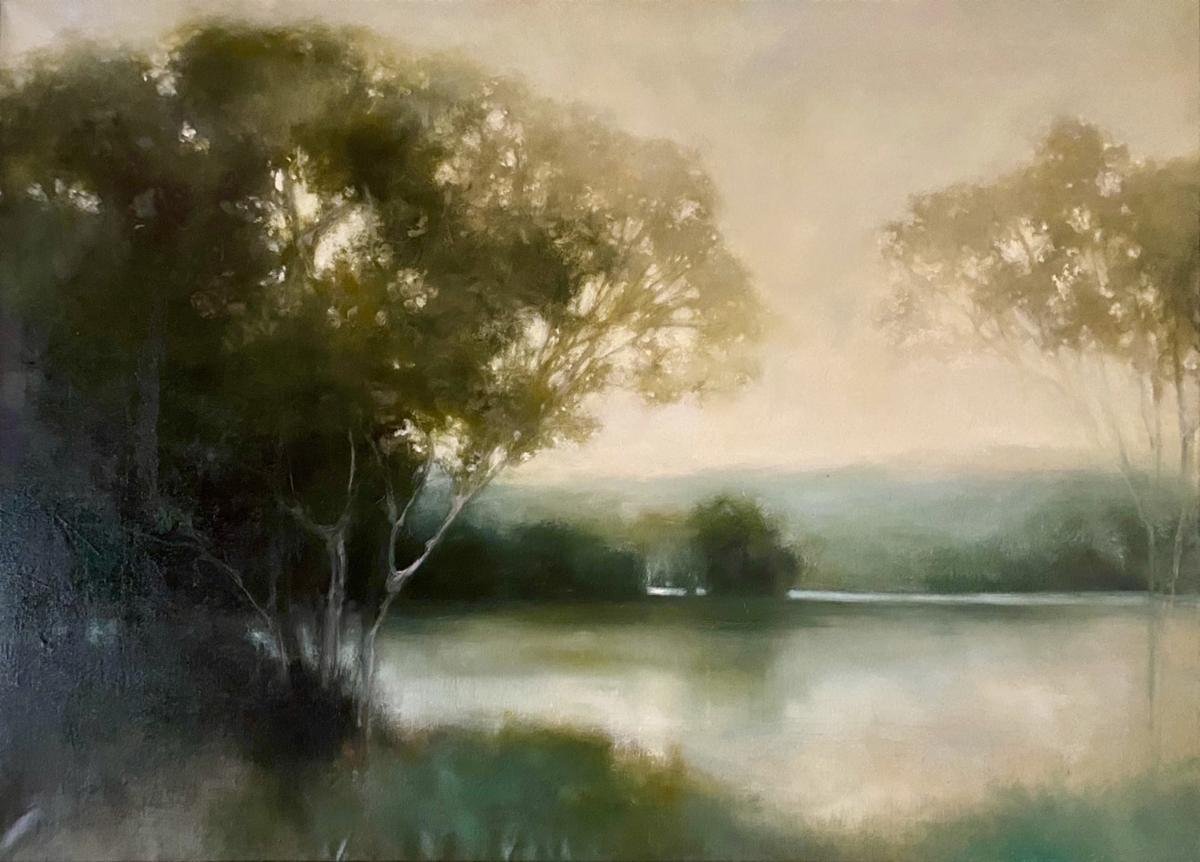

“An Interesting Light’’ (oil on canvas), by Julia Purinton, of Warren, Vt., (see below) at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury Vt.

The gallery says:

Ms. Purinton “blends the distinguishable with the imagined, creating dreamlike landscapes in oil. The context of time and place for each work is gracefully ambiguous allowing the viewer to interpret the composition in a personal way.

“Setting a mood with her soft, subtle palette, Purinton begins a story and leaves the ending for us to construct.’’

At the Sugarbush ski area, in Warren, in February. The Warren area is a major recreational and second-home area, anchored by Sugarbush. It also has many artists.

— Photo by TaraMGordon -

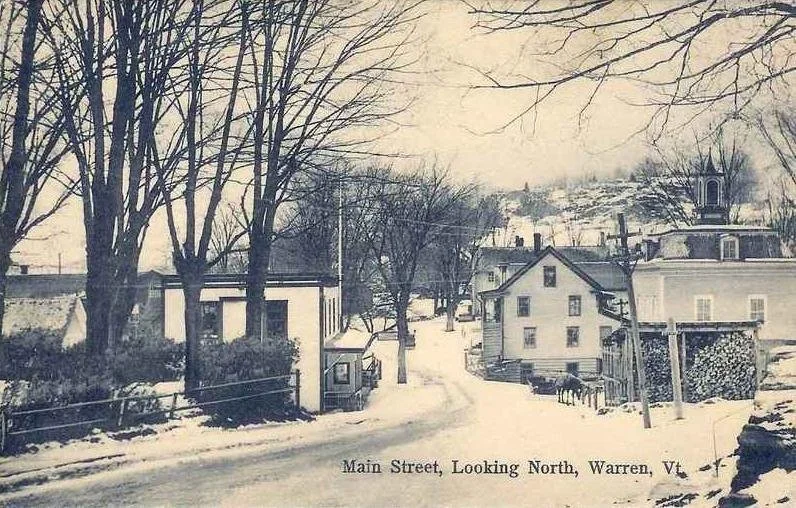

In 1910, way before the ski boom.

The wet look

Sunny day flooding in Miami during a “king tide’’.

Coastal flooding in Marblehead, Mass., during Superstorm Sandy on Oct. 2012.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The stuff below is a heavily edited version of some of the remarks I made in a talk a couple of weeks ago and seem to me particularly resonant as we head into summer coastal vacation season:

Most of us are in denial or oblivious when it comes to sea-level rise caused by global warming. For example, Freddie Mac researchers have found that properties directly exposed to projected sea-level rise have generally gotten no price discount compared to those that aren’t, though that may be changing. And some states don’t require sellers to disclose past coastal floods affecting properties for sale. Politicians often try to block flood-plain designations because they naturally fear that they would depress real-estate values.

So the coast keeps getting more built up, including places that may be underwater in a few decades. It often seems that everyone wants to live along the water.

As the near-certainty of major sea-level rise becomes more integrated into the pricing calculations of the real-estate sector, some people of a certain age can get bargains on property as long as they realize that the property they want to buy might be uninhabitable in 20 years. Younger people, however, should seek higher ground if they want to live near the ocean for a long time.

A tricky thing is that real estate can’t just be abandoned—it must pass from one owner to another. Some local governments’ coastal permits require owners to pay to remove their structures when the average sea level rises to a certain point. Absent such requirements, many local governments’ budgets may not be enough to pay for demolition or the moving costs associated with inundation. There are some interesting liability issues here.

What to do?

Administrative mitigation would include raising federal flood-insurance rates and more frequently updating flood-projection maps. More localities can take stronger steps to ban or sharply limit new structures in flood-prone areas and/or order them removed from those areas. And, as implied above, they should implement flood-experience-and-projection disclosure requirements in sales documents.

As for physical answers to thwarting the worst effects of sea-level rise, especially in urban areas, many experts believe that some form of the Dutch polder approach, which integrates hard stone, concrete or even metal infrastructure, and soft nature-based infrastructure, along with dikes, drainage canals and pumps, may have to be applied in some low places, such as Miami and Boston’s Seaport District. Barrington and Warren, R.I., look like polder country.

Polders are large land-and-water areas, with thick water-absorbent vegetation, surrounded by dikes, where the ground elevation is below mean sea level and engineers control the water table within the polder.

Just hardening the immediate shoreline, and especially beaches, with such structures as stone embankments to try to keep out the water won’t work well. That just makes the water push the sand elsewhere and can dramatically increase shoreline erosion.

On the other hand, creating so-called horizontal levees – with a marshy or other soft buffering area backed with a hard surface -- can be a reasonable approach to reduce the impact of storms’ flooding on top of sea-level rise.

Certainly establishing marshes (and mangrove swamps in tropical and semi-tropical coastal communities) can reduce tidal flooding and the damage from storm waves, but that may be a political nonstarter in some fancy coastal summer- or winter-resort places. Then there’s putting more houses and even stores and other nonresidential buildings on stilts, though that often means keeping buildings where safety considerations would suggest that there shouldn’t be any structures, such as on many barrier beaches. Still, it would be amusing to see entire large towns on stilts. Good water views.

Oyster and other shellfish beds can be developed as (partly edible!) breakwaters. And laying down permeable road and parking lot pavements can help sop up the water that pours onto the land. I got interested in how shellfish beds can act as a brake on flood damage while editing a book about Maine aquaculture last year. Of course, the hilly coast of Maine provides many more opportunities to enjoy a water view even with sea-level rise while staying dry than does, say, South County’s barrier beaches.

In more and more places where sea-level rise has caused increasing ‘’sunny day flooding’’ -- i.e., without storms -- streets are being raised.

I’m afraid that, barring, say, a volcanic eruption that rapidly cools the earth, slowing the sea-level rise, the fact is that we’ll have to simply abandon much of our thickly developed immediate coastline and move our structures to higher ground.

Working-waterfront enterprises -- e.g., fishing and shipping -- must stay as close to the water as possible. But many houses, condos, hotels, resorts and so on can and should be moved in the next few years. If they don’t have to be on a low-lying shoreline, they shouldn’t be there as sea level rises. For that matter, entire large communities may have to be entirely abandoned to the sea even in the lifetime of some people here.

Coastal communities and property owners face hard choices: whether to try to hold back the rising ocean or to move to higher ground. Nothing can prevent this situation from being expensive and disruptive.

Common sense would suggest that we not build where it floods and that we should stop recycling flooded properties. Again, flood risks should be fully disclosed and we need to protect or restore ecologies, such as marshes, shellfish and coral reefs and dune grass, that reduce flooding and coastal erosion.

Nature wins in the end.

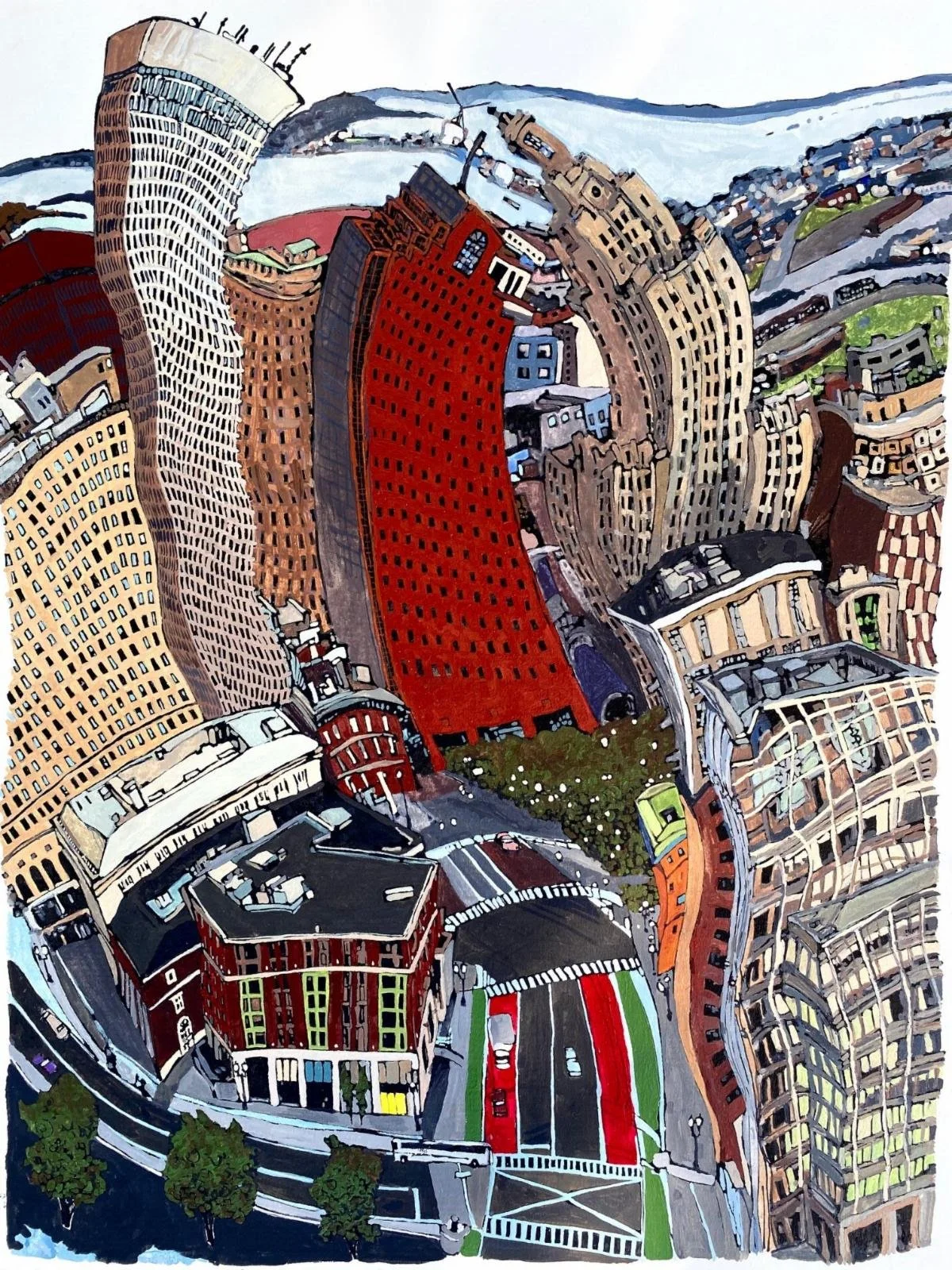

Plastic Providence

This work by Rhode Island artist Jim Bush can be seen at the Providence Art Club March 6-25.

Here’s his description of his background:

“Jim Bush grew up in Cambridge, Mass., and graduated from Kenyon College with a double major in Studio Art and Political Science. He is an award-winning artist, member of the Providence Art Club and a former member of the Sakonnet Artists Cooperative, in Tiverton, R.I. His editorial cartoons appeared in The Providence Journal from 1994-2012. Nationally his cartoons have appeared in the Washington Post National Weekly Edition, The Dallas Morning News and he has drawn for the Tribune Media Services College Press Syndicate.

“In 2007, Jim purchased a building in the historic district of downtown Warren, R.I. and spent a year converting it into an art studio and gallery. Jim focuses now on his fine art painting, primarily acrylic and watercolor. He enjoys painting animals, seascapes, landscapes, farm scenes, architecture -- life around him. His style continues to reflect his cartooning foundation, often displaying his subjects in a light-hearted and off-beat way.’’

Sign up now for last weeks of winter light

“Song of Winter Pool’’ (oil on linen) by Rory Jackson in his Edgewater Gallery show “Blanket of Stillness: Winter in the Mad River Gallery’’ at the Pitcher Inn, Warren, Vt., through March 22. Edgewater (based in Middlebury, Vt.) says Mr. Jackson “captures the unique beauty of the low winter light on the open fields, slopes, forests and mountains of (Vermont’s) Mad River Valley.’’

Lincoln Peak, West View (oil on linen)

In 1910

The tie-loving ghost

“Last night my color-blind chain-smoking father

who has been dead for fourteen years

stepped up out of a basement tie shop

downtown and did not recognize me.’’

— From “My Father’s Neckties,’’ by Maxine Kumin (1925-2014), a U.S. poet laureate and Pulitzer Prize-winner and a Warner, N.H., horse farmer.

Statue of New Hampshire Gov. Walter Harriman in Ms. Kumin’s town of Warner, N.H.

A lovely down-to-earth downtown

Excerpted from GoLocal24's "Digital Diary'' column.

Congratulations to downtown Warren, R.I., for being named one of “America’s 5 Great Neighborhoods’’ by the American Planning Association for the town’s “foresight, innovation, and cooperation” in building a better place.

It has always seemed to me a bit of a miracle that downtown Warren has been able to maintain its shops, restaurants and other signs of being a healthy old-fashioned, pre-mall downtown. That Warren is not a rich town and that its downtown is not an all-too-precious place like, say Stockbridge, Mass. (where Norman Rockwell worked) or Nantucket makes it all the more attractive.

-- Robert Whitcomb