A Wampanoag’s suppressed speech on tribe’s sad history

Fanciful version of Wampanoag SachemMassasoit smoking a ceremonial pipe with Plymouth Plantation Gov. John Carver in 1621.

To have been delivered at Plymouth, Mass., 1970

ABOUT THE DOCUMENT: Three hundred fifty years after the Pilgrims began their invasion of the land of the Wampanoag, their "American" descendants planned an anniversary celebration. Still clinging to the white schoolbook myth of friendly relations between their forefathers and the Wampanoag, the anniversary planners thought it would be nice to have an Indian make an appreciative and complimentary speech at their state dinner. Frank James was asked to speak at the celebration. He accepted. The planners, however, asked to see his speech in advance of the occasion, and it turned out that Frank James' views — based on history rather than mythology — were not what the Pilgrims' descendants wanted to hear. Frank James refused to deliver a speech written by a public relations person. Frank James did not speak at the anniversary celebration. If he had spoken, this is what he would have said:

I speak to you as a man -- a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction ("You must succeed - your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community!"). I am a product of poverty and discrimination from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome, and to some extent we have earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first - but we are termed "good citizens." Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to be so.

It is with mixed emotion that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you - celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back, of reflection. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People.

Even before the Pilgrims landed it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans. Mourt's Relation describes a searching party of sixteen men. Mourt goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indians' winter provisions as they were able to carry.

Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people.

What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years?

History gives us facts and there were atrocities; there were broken promises - and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries, but never before had we had to deal with fences and stone walls. But the white man had a need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only ten years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the souls of the so-called "savages." Although the Puritans were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other "witch."

And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands taken and, in token, reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could only stand by and watch while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian could not understand; for to him, land was survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It was not to be abused. We see incident after incident, where the white man sought to tame the "savage" and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early Pilgrim settlers led the Indian to believe that if he did not behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again.

The white man used the Indian's nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman -- but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man's society, we Indians have been termed "low man on the totem pole."

Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives - some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokee and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoag put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man's way for their own survival. There are some Wampanoag who do not wish it known they are Indian for social or economic reasons.

What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and live among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they live as "civilized" people? True, living was not as complex as life today, but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their [the Wampanoags'] daily living. Hence, he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious, and dirty.

History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt, and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood.

The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be the image the white man has created of the Indian; his "savageness" has boomeranged and isn't a mystery; it is fear; fear of the Indian's temperament!

High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of our great Sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man caused us to be silent. Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We ARE Indians!

Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the whites did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American prisoners of war in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently.

Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting We're standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we'll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us.

We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail.

You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian.

There are some factors concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across this vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as a white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs. We're being heard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have the unique culture, we still have the will and, most important of all, the determination to remain as Indians. We are determined, and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only the beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours.

Wamsutta

September 10, 1970

Jim Hightower: Turkey and Thanksgiving confusions

“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth “ (1914), by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, at the Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Mass. If they ate turkeys, they would have been members of the Eastern Wild Turkey subspecies seen below.

Via OtherWords.org

Let’s talk about turkey!

No, not the Butterball now pouting in the Oval Office. I’m talking about the real thing — the big bird, 46 million of which Americans will devour on Thanksgiving.

It was the Aztecs who first domesticated the gallopavo, but leave it to the Spanish conquistadores to “foul-up” the bird’s origins.

The Spanish declared the turkey to be related to the peacock — wrong! They also thought that the peacock originated in Turkey – wrong again! And they thought that Turkey was in Africa. You can see the Spanish colonists were pretty confused.

Actually, the origin of Thanksgiving itself is similarly confused.

The popular assumption is that it was first celebrated by the Mayflower immigrants and the Wampanoag natives at Plymouth in what is now called Massachusetts, 1621. They feasted on venison, neyhom (Wampanoag for gobblers), eels, mussels, corn and beer.

But wait, say Virginians, the first precursor to our annual November food-a-palooza was not in Massachusetts — the Thanksgiving feast originated down in Jamestown colony, back in 1608.

Whoa, there, hold your horses, pilgrims. Folks in El Paso, Texas, say that it all began way out there in 1598, when Spanish settlers sat down with people of the Piro and Manso tribes, gave thanks, then feasted on roasted duck, geese and fish.

“Ha!” says a Florida group, asserting the very, very first Thanksgiving happened in 1565, when the Spanish settlers of St. Augustine and friends from the Timucuan tribe chowed down on cocido — a stew of salt pork, garbanzo beans, and garlic — washing it all down with red wine.

Wherever it began, and whatever the purists claim is “official,” Thanksgiving today is as multicultural as America. So let’s enjoy — even if we’re in smaller groups or observing virtually this year.

Kick back, give thanks we’re in a country with such ethnic richness, and dive into your turkey rellenos, moo-shu turkey, turkey falafel, barbecued turkey.

Jim Hightower is a columnist and public speaker.

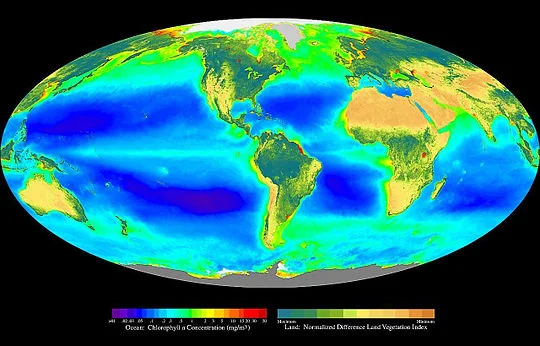

Tim Faulkner: Trump vs. the biosphere?

The day after Donald Trump’s surprise election win, the mood among environmentalists was, as expected, glum.

During his campaign, Trump, a climate-change denier and fossil-fuel proponent, vowed to withdraw from global climate treaties and neuter the Environmental Protection Agency. All told, his candidacy was considered a colossal threat to the biosphere.

Now that he’s two months away from taking office, it’s mostly guesswork as to which of Trump’s grand proclamations of environmental ruin will become reality.

Nationally, environmentalists expect that, at least, the goal of limiting temperature rise to 2 degrees is a lost cause, as is limiting atmospheric carbon dioxide to less than 400 parts per million.

To deal with their anxiety, environmental groups such as 350.org are encouraging environmentalists to partake in peaceful protesting. The National Resources Defense Council hosted a conference call for the aggrieved Nov. 10 titled “Defending Our Environment from the Trump Presidency.”

The consensus response from local government officials is to embrace autonomy.

“(Trump's win) puts an even greater burden on states to take action and be creative,” Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo said during a Nov. 9 meeting of the Rhode Island climate council.

Raimondo received an update on Rhode Island’s long-term emissions-reduction plan. She and agency and department officials gave no indication of changing course on climate adaptation and mitigation efforts.

Raimondo said it's not known what Trump will do with President Obama’s Climate Action Plan. But Trump’s unexpected victory creates urgency to move forward with local initiatives, she added.

“Norms change in times of crisis, and I do believe we are facing a climate-change crisis, so we do have to get people to take action,” Raimondo said.

The governor confirmed that she isn't changing her neutral-to-favorable position on the proposed fossil-fuel power plant in Burrillville, a project that would be the state’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Janet Coit, director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, told ecoRI News that Trump’s victory was sobering. “It means we have to work all the harder.”

Fortunately, Rhode Island is surrounded by states with shared regional and local environmental goals, Coit said.

If federal support and guidance declines, she said, “Now we have to stop, regroup and guess that the leadership will have to come from the state level. I guess we have to look to ourselves more.”

Ken Payne, chair of state renewable energy committee, as well as food and farm programs, said the election means that progress on these issues will not only have to come from the state, but from communities and neighborhoods. Before the election, he and Brown University Prof. J. Timmons Roberts announced plans to launch a new, non-government affiliated group to advance green initiatives.

Roberts wasn't at the recent climate council meeting; he's in Morocco with students researching the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations.

In an article for Climate Home, he echoed the wait-and-see refrain put forth by environmental experts who wonder if the country and climate policy will be governed by Trump the negotiator or Trump the tyrant.

“So which Trump will govern? There is cause for both hope and fear,” Roberts wrote.

To others, fear caused by the election affirms reality. Morgan Victor of the Pawtucket-based environmental activist group The FANG Collective, said Trump’s win is evidence of American ongoing legacy of colonialism and slavery.

“It’s a reality that white supremacy runs in this country both overtly and covertly,” Victor said.

The Providence resident and member of the Wampanoag tribe participated in the ongoing Standing Rock Sioux pipeline protests taking place in North Dakota.

Having Trump in office will justify more attacks against indigenous groups and their land, Victor said.

“It’s scary. I hope it wakes people up, especially white people, to take care of the ones they love,” she said.

Tim Faulkner writes for ecoRI News.