Gerald Mallon: Devotion and death in Vietnam

Mr. Mallon is at the left, with the M-16 and side arm. He wrote that the Marine at the right “had taken a couple of rounds in his pelvis and had his guts in a bag the next time we met, in St. Albans Naval Hospital (in New York). He weighed about 90 pounds and looked like a skeleton. I can't remember his name but he was eventually healed, gained some weight and was retired.’’

Mr. Mallon wrote: “The smoke is from napalm - this is the single most terrifying weapon I've ever witnessed. I was in Japan (106th Army Hospital Yokosuka) down the hall from the burn ward...that was almost unbearable to see and imagine the pain involved. No matter how f— up you were - there was always someone worse off.’’

I met Cpl. Richard Clark Abbate in early January 1968, when the 3rd Battalion, 27th Marines was formed at Camp Pendleton to be deployed to Vietnam. Richard, myself, L/Cpl. Richard Belcher and PFC Gary Trott constituted a gun team with the 1st Platoon of M “Mike” Company. As team leader, Richard was responsible and caring in executing his duties. He was older, married and had been in the Corps longer than any of us. As we served together, sharing the hardship of Vietnam, we came to like him as a friend and respect him as a leader.

On May 18, at 930 we were airlifted out by helicopter to join a battle that had developed as a result of a spoiling attack code-named Operation Allen Brook. On May 17 India Company had encountered strong enemy forces on Go Noi Island. It was not truly an island, but the monsoons would flood the Ky Lam, Thu Bon, Ba Ren, and Chiem Son rivers and isolate it. It was a staging area for elements of three Viet Cong (VC) battalions and a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regiment building up for an attack on Da Nang. It took about 20 minutes to fly from Cau Ha Base Camp to Go Noi Island. Upon landing, we could hear explosions and see the tracers of rifle and machine-gun fire. Mortar rounds were coming in on our direct front. Our platoon commander told us to drop our extra gear, get down and move to the front. Enemy fire was relentless, hot and heavy. The Landing Zone (LZ) was in a defilade with a river at our back so we began to crawl to the “sound of the guns.” Our company was spread out in an area that was exposed and in front of a tree line with only paddy dikes, scrub and elephant grass for cover.

We advanced into a hail of rifle and machine-gun fire, rocket-propelled grenades and mortar fire from well-concealed bunkers, and we were pinned down by the withering fire from behind a paddy dike. The cacophony was intense and the adrenaline shock of combat surreal in its intensity. The gunfire and flying shrapnel a foot above ground were so concentrated that getting up and moving meant certain death. Marines lay in front of us – dead and dying. Despite repeated attempts, we made little headway against the enemy defenders fighting from the bunkers. Unable to advance or withdraw, we called for 105mm artillery and 81mm mortar fire on the enemy positions in the tree line. We swept supporting fire swept back and forth, with it landing within 50 yards of our lines.

Over the next several hours I fired back and forth, saturating the tree line. My M-60 machine gun began to smoke and developed a feed malfunction. We sent our ammo humper, Gary Trott, back to get more ammunition, water and another barrel for the gun. Abbate and Belcher covered me as I crawled forward to reach a critically wounded Marine, PFC Donald Byron Jones, about 15-20 yards to our right front. He had been shot through the chest and was lying on his back in an exposed position. I reached him, grabbed his ankle and rolling on my side tried repeatedly to drag him, but his utility belt with the canteens attached dug into the sand and I couldn't move him. Jones was turning blue and choking, his eyes staring blankly into oblivion. I got over him and used two fingers to clear his mouth so that he could breathe. That was when Richard appeared and began to take off the utility belt by kneeling over him between Jones’s legs. I looked at Richard, saying nothing, and began to apply a pressure bandage to Jones’s chest wound. Richard was about a foot or two away from me to my left side. I struggled to focus my attention on Jones, blocking out everything else.

It felt like a baseball bat slamming me when the bullet hit. It went through my right elbow, spinning me around, and lodging in my upper left arm. Blood seemed to explode from Richard’s face as he pitched forward. He died instantly. Disoriented, I lay there for the next hour or so talking to Jones, trying to reassure him as he slowly choked to death. I slowed the bleeding from my elbow by tying a makeshift tourniquet and putting two fingers into the gaping hole in my joint. I had blood on my chest from the wound in my left arm, and was breathing tentatively: I thought that I had been shot in the chest and feared that I would choke to death like Jones. I made the usual bargain with God to save me. Hearing the roar of jets, I looked over my right shoulder. Two planes flying parallel to our lines seemed to peel off as four canisters of napalm, tumbling wildly, hit the tree line and exploded in a huge fireball. The napalm was close enough that I felt its heat on my face. I could taste the acrid vomit in my mouth and feared that I might burn to death in the next pass, but the fire’s volume subsided.

Dazed and weak, I was grabbed by the shoulders, jerked to my feet and half dragged to the LZ. My wounds were bandaged, morphine administered, and I was led to a waiting Medivac. Before they could load me and another casualty they had to get rid of two dead Marines to make room. The crewmen lifted a poncho and two bodies rolled out like nothing special. It was over for them and it didn’t matter anymore. The helicopter lifted off and soon I arrived nauseated and shaking at a surgical unit in Da Nang – my ordeal over.

That day still echoes in my memory. I’ve reflected on the randomness of death and how lucky I’d been. After all, the bullet that killed Richard had passed within inches of my face, sparing me.

I’ve always felt deep regret for Richard’s death. I should have known that he would come to help me because that was the Marine and man he was. I often replay the events of that day, feeling the ache of having lost a friend. I wonder what life would have held in store for Richard and our other fallen comrades if they hadn’t died in Vietnam, and I feel a deep sadness when thinking of their stolen futures. I don’t know if there were worse places to be than where we fought, but I am proud to have been with “Mike” Company on that day. Every Marine in 3/27 still remembers the brothers we left behind. Richard was, and is, my brother and I miss him even now. He was one of the finer men among the Marines I have known. War is fearful, dirty and brutal but my life’s trajectory has been set by the experience…

“Through our great good fortune, in our youth are hearts were touched by fire.”

-- Oliver Wendell Holmes

In the fighting on Go Noi Island, the four companies of 3/27 lost 172 dead, with another 1,124 wounded in action. Richard Clark Abbate was one of six Marines from M Company killed in action on May 18, 1968. Enemy casualties during Operation Allen Brook were 1,017 killed and three captured. {how many wounded?} The battle at Go Noi Island remains one of most harrowing and sanguinary combat operations in Vietnam but it eliminated any direct threat to Da Nang.

“This is my commandment, that ye love one another as I have loved you. Greater love hath no man than this; that he lay down his life for his friends.”

-- John 15: 12-13

Gerald (Jerry) Mallon lives in Michigan. He arrived in Vietnam a private first class and was promoted to lance/corporal after being shot.

He’s a fellow member of an email group including New England Diary editor Robert Whitcomb.

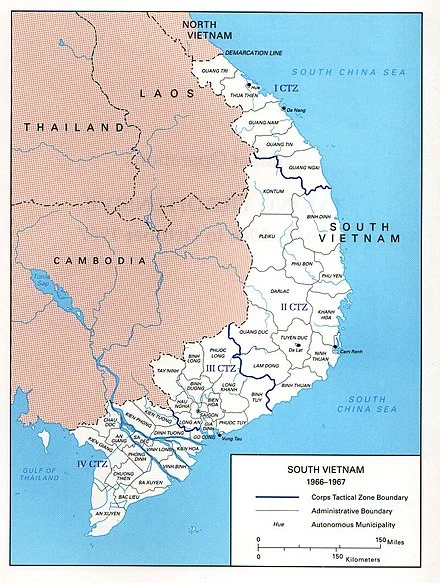

Open field fighting in Vietnam.

Da Nang, referenced in this essay, is on the ocean toward the upper right.

Llewellyn King: Novel revives Vietnam War memories and lessons

The Vietnam War was much with me. I never made it to Vietnam during the war. But the war came to me in every job I had between 1961 and 1973.

It is not that I did not try to get to Vietnam as a correspondent, or even as a soldier. I registered for the draft when I arrived in the United States in 1963, but I was rejected because my eyesight was poor, I was married, and I was too old.

I started my long-distance association with the war when I was working for Independent Television News in London in 1961, and continued it when I moved over to the BBC. I was always selected as the writer for the Vietnam segments.

At The Herald Tribune in New York, on my first night, I was asked to pull all the files together for the lead story: Vietnam. Later at The Washington Daily News and The Washington Post, Vietnam always found me.

Now comes a novel and the war finds me again, as I read about correspondents David Halberstam and Peter Arnett; U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin, who was delusional about the situation; Nguyen Van Thieiu, the president of South Vietnam until his ouster. It is all as fresh as if it were the file coming off the teleprinter today.

The novel is Escape from Saigon and its authors, Michael Morris and Dick Pirozzolo, tell the last, desperate days of Saigon in 1975. It is a novel where the end is known, but not known; where the tension ratchets up each day of the countdown to evacuation on April 29.

In Washington, Congress had refused President Gerald Ford’s last attempt to bolster aid to South Vietnam with a final $722 million. The major U.S. military participation ended with the peace treaty of 1973. For two years, the South Vietnamese had struggled on with U.S. support but without ground troops. The North Vietnamese would roundly violate the peace, and the South Vietnamese would live in hope that the United States would not let them be overrun. Forlorn hope.

The United States had lost interest in the war, after it had been so torn apart by it, and wanted no more part of a land war in Asia, or at that time, a land war anywhere. More than 58,000 Americans and an untold number of Vietnamese had perished.

Lessons? You draw them: secret plans, ground troops, aerial war, insuperable U.S. military might. These ideas are flying again about other regions of the world. Beware. Read this novel.

I have often thought that if the Kennedy brain trust had read The Quiet American, Graham Greene’s masterful novel about Vietnam, published in 1955, things would have turned out differently. We might have shunned involvement on the election of Jack Kennedy.

Escape from Saigon has the same ring of authenticity. It should: the authors both served in Vietnam. Morris was sent to Vietnam when he was just 19 years old and, as an infantry sergeant in Northern 1 Corps, he saw some of the fiercest fighting of the war. He was wounded and his bravery was rewarded with a Purple Heart.

Pirozzolo was an Air Force information officer in Saigon. Perhaps that is why the city is so well described, from the watering holes to hotels, like the Caravelle and the Continental, where so many journalists stayed and drank. Drinking was a part of Saigon in war.

When I finally made it to Vietnam, in 1995, I traced the war from Hanoi, replete with its French boulevards down through Da Nang, Hue and China Beach. All so peaceful, after so much bloodshed. Battlefields are that way.

Escape could be a sad book, or a book of recrimination, or an attack on the American role. Instead, it is a novel of facts told through the lives of the people: journalists, a bar keeper, a priest, a CIA official, South Vietnamese who worked for the Americans and sometimes betrayed them, and those who fled by plane and boat.

The novel is exceptional in authenticity. Its portrait of a city in extremis is chilling and completely engrossing. It will take many back and some forward -- forward to new foreign involvements.

Llewellyn King (llewellynking1@gmail.com) is executive producer and host of “White House Chronicle,” on PBS.