John Sideli and ‘the strange liberty of creation’

John Sideli with some of his creations

VERNON, Conn.

The ancient Greeks have a saying: “To meet a friend again after a long absence is a god.”

My wife, Andrée, and I have known John Sideli for more than 60 years. After a long absence, we met again in Bristol, R.I., where, close by in Warren, Andrée and I enjoyed a brief vacation. As the word “vacation” suggests, times spent in this way together are best savored without all the modern inconveniences: no computers, no phones, and, in my case, no newspapers -- seven days, a full week, of serendipity, and a welcomed respite from the drudgery of column writing.

Andrée has always said that political writing is a bit like scrawling a message with your finger on a strand of tide-hardened beach before the tide rushes in to erase it.

On day three, she smiled mischievously and said, “I’ve arranged a surprise for you. I’m sure you will be pleased. I can’t tell you what the surprise is, because then it will be no surprise.” There were no flaws in this logical construction.

The surprise was John Sideli, changed somewhat from the Sideli I knew six decades earlier and now living in Bristol. But the point of the Greek saying is that memories, sleeping in the brain for years, are always youthful. They stir and come to life when, after a long absence, we meet an old friend again.

Sideli’s first love was antiques, and he had a jeweler’s eye for beauty, always an enticing mistress. He was a purveyor of cluttered antique shops, junk yards and astonishing roadside finds. The eye that pierces through facades and strikes at the bone and muscle of things, destructs and constructs anew. And if it is an artist’s eye, the new construction carries within it the essence of things. All art is a reconstruction of buried narratives brought to life again by the work of the artist.

There is in Sideli’s works a living drama, the result of separate pieces of time cunningly brought together in a frame. Quite like characters in a play, these essences, alive and jostling each other, produce in a viewer pity, sorrow, laughter, tears, all the ragged radiations of a drama. They tell, they speak to the viewer. And what the viewer carries away from the encounters depends, ultimately, on what he or she brings to them.

In 1968, Sideli found himself caretaking for two years at the Roxbury, Conn., estate of the very much in demand and famous sculptor Alexander Calder, noted for his stabiles and mobiles. The experience was transformative. In some of his pieces, Calder had been collecting and putting together – deliberatively and artfully, not randomly – certain found objects that had appealed to his aesthetic sensibilities. Calder at play, it turned out, had a very well developed sense of humor present in many of his pieces. During a visit to the estate, I remember in particular a playful tabletop carousel, art and humor shaking hands and greeting each other as old friends.,

At the same time, Sideli had been collecting various bits and pieces that had appealed to him. “I realized,” Sideli noted in a Hirschi & Adler showing in New York in 2013, “why I had been collecting these fragments, bits and oddities. I was amazed by the way they would take on a new meaning when juxtaposed in different contexts. They would acquire a kind of narrative aspect and even evoke a sacred mood in a very short time. I became a champion of the art of everyday objects.”

We were seated in Sideli’s modest living room, surrounded and captivated by his enticing “mixed media constructions.” That verbal construction belongs to Riviére, at Robert Young Antiques of Battersea Bridge Road, London, an antique dealer that featured Sideli some years ago.

He was showing me some photos, some of which he had sold at mouthwatering prices to all and sundry -- millionaires, workmen, professionals of every stripe, including butchers, bakers and, for all I know, candlestick makers.

Two people had come into his then-shop in Wiscasset, Maine, looked around a bit, and the female almost immediately pointed to a humorous rendition and said, “That’s it. That’s the one I want.”

Such decisions are easily made because it is impossible not to have a conversation with the Sideli piece you love, and many purchases are the result of love at first sight. Recently, Sideli asked his daughter – trying his best to be uncomplicated -- which of the pieces she would like after he had gone the way of all flesh.

Answer: “All of them.”

“The color in this one,’’ I said, “is farm tractor red.”

“That is because the metal plate [featured in the piece] came from a tractor, or part of a roof, painted tractor red, that housed the tractor in an out-of-the way place in Costa Rica.”

Naturally, a narrative attached to the art work.

The farmer from whom Sideli had procured the plate was irascible, with a short temper, not unusual in intensely practical farmers everywhere. Farmers want to be about their business. Intrusions not business related tend to be costly. The man was cocking a poisonous eye at Sideli, who had, very politely, asked the farmer whether he might be willing to carve out a piece of his farm equipment for an art project. The price was right, the thing was done, and I was now staring at the final product.

Most of Sideliworks are tinted with humor, as are most of the conversations I’ve had with Sideli. That is because humor is always the result of a joyful asymmetry, an incongruous mixing of tragedy and comedy, a disproportion that strikes the fancy immediately, the way a hammer strikes the gong.

“That’s the one I want.”

Years after Sideli had returned to America from Costa Rica, where he had been living for a few joyous years, he returned to the farm, surprised to see the old farmer was still among the living.

“I doubt you remember me,” Sideli said to the farmer.

Some people, and some circumstances, are unforgettable.

“Oh, I remember you alright.”

Strolling the streets of Costa Rica, Sideli was struck by the various colors of metal street plates, all of them softened by years of sun and rough weather but, like distant stars, still shining brightly.

“I went in search of some cast off plates and found a shop that replaced them.”

He said to the owner of the shop, “I’d like to buy those used plates.”

Big smile! Here was an American with money.

“I have some new plates right over here.”

“No, no. I don’t want the new plates. I want these old plates, no others. How much?”

The two arrived at a price, and Sideli carried off the used plates as if they had been venerable religious objects.

French author and philosopher Albert Camus lived his life – much too brief, as it turned out -- with his eyes wide open. We tend to forget that all art is a transcendent product of time and space. “To create today,” Camus tells us, “is to create dangerously… The question, for all those who cannot live without art and what it signifies, is merely to find out how, among the police forces of so many ideologies… the strange liberty of creation is possible.”

“Protect the Innocent’’

The construction of “Protect the Innocent” began with a news account of a horrific rape in South America, Shortly after the account appeared, Sideli noticed two white, truncated mannequins lying in mud, discarded on the roadside. He washed them carefully and brought them home. The viewer will notice the saw-toothed metal rim of the frame. The mannequins, draped in tassels, are immaculate but vulnerable and white as a communion wafer.

In an artist’s note Sideli writes, “I assemble and arrange objects in the same way that a poet chooses words. I try to carefully combine them in a way that allows them to transcend their original form or purpose and evoke a feeling or tell a story. And as with poetry, there is a certain rightness to a particular combination or arrangement that will express with directness and simplicity what I want to say.

“I believe that there is spirit in matter, which, if tapped, can have a powerful resonance when objects are carefully tuned, coaxed, combined and juxtaposed.”

The sensuous penetration of all art depends ultimately upon the presence of the artist in the work and the attention viewers or auditors bring to it.

Those lucky enough to own a Sideli art work will find they need never be alone. Sideliworks, like the remembered poem, stay with you, a faithful companion, when everyone else has left the room.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

#John Sideli #Don Pesci

Don Pesci: What is a woman?

Detail from Johannes Vermeer’s (1632-1675) “Portrait of a Woman With a Pearl Earring’’

VERNON

The absurdities of post-modern life press upon us like some finely tuned, automatically updated incubus.

Awaiting approval for her nomination to be on the U.S. Supreme Court, current Associate Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was asked, by a woman legislator, as it happened, to “define a woman.”

She demurred, modestly pleading that she was no biological scientist.

But the question, not entirely innocently presented, begs to be answered. When I put the question to two politically unbiased women, both agreed that a “woman” may be defined as one who receives flowers from a male admirer.

I cannot remember ever having received a bouquet of flowers from a woman. I have given out a few bouquets of flowers to women I admire and cannot recall ever having sent a bouquet to a man.

So far, so good.

Naturally, there are exceptions, but exceptions generally prove the rule, except in rare cases when it becomes politically expedient to make a rule of an exception. This nearly always ends in disaster. Both rules and definitions should be generally accepted by what the ordinary run of humanity would regard as objective and dispassionate observers.

My grandfather – Carlo “The Fox” – stands out as an exception … sort of.

One day, when I was storming through my reckless teens, “The Old Man,” as everyone affectionately called Grandfather Carlo, showed up at the Pesci homestead clutching a fist full of Bennies, which he pressed upon his daughter Rose, my mother.

This took her, the immediate family, the extended family and, for all I know, any relatives in Italy who knew Carlo well, by surprise. Carlo The Fox was abstemious when it came to money, not exactly a Scrooge, but close.

“What’s this for?” my mother asked.

Sitting by the kitchen window, the early morning sun bathing his weather ravaged face, he explain that he was old.

My mother nodded assent, a question mark mysteriously appearing on her forehead.

He sipped his “coffee royal” -- steaming hot black coffee, just short of an espresso, never to be diluted with anisette -- while his daughter waited patiently for him to explain why on this day he had abandoned a lifetime of penny-pinching. To be sure, he had in the past made rare exceptions to his inflexible habit, most often when he was engaged in card games for money, not sport. In one game, he had won, and then lost a portion of Elm Street in Windsor Locks, Conn.

My mother groaned when she discovered this. “We could have been rich,” she observed.

Rose waited him out. And, sipping his coffee, to which was added a knuckle of Jack Daniels, it came bubbling out of him like a freshet of living water.

He did not expect to live too many years longer, most of his friends were dead, he could not – dare not! – trust anyone with the mission he assigned my mother. When he died – unfortunately the fate of all men, rich, poor and moderately well-off – she was to take the money and with it buy flowers for his wake and funeral. He did not want to go out un-flowered or unrespected by the few of his friends who might survive him.

My mother, who had gotten used to her father’s abstemiousness -- though he had made an exception in the case of coffee-royals and Italico Classico Ammezzato cigars, a refined blend of Italian and Kentucky, he was pleased to note -- was touched and instantly accepted the commission. When Carlo The Fox died, his body was smothered in flowers.

So here was a woman buying flowers for a man – to be sure, with the man’s money – an exception that proves the rule.

Few of us are linguistic scientists or professors of grammar, morphology, syntax, phonology, phonetics, and semantics. We are not Noam Chomsky, a reliable guide when he does not meander outside his discipline. The definition of a woman as “one who receives flowers from an admiring gentleman” is serviceable and practical, allowing for arcane exceptions that, given the postmodern bad habit of redefining foundational characteristics, does not touch embarrassing and painful questions such as “Should elementary school libraries stock Gender Queer and Lawn Boy?”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

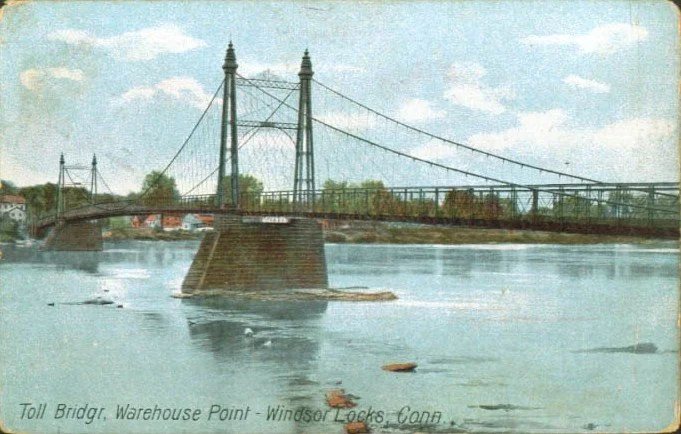

Toll bridge over the Connecticut River, c. 1910.

Don Pesci: An apolitical and literary jaunt in The Berkshires

A view of the Mt. Greylock Range from South Williamstown (from the west). The Hopper, a cirque, is centered below the summit.

—Photo by Ericshawwhite

Arrowhead, where Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick.

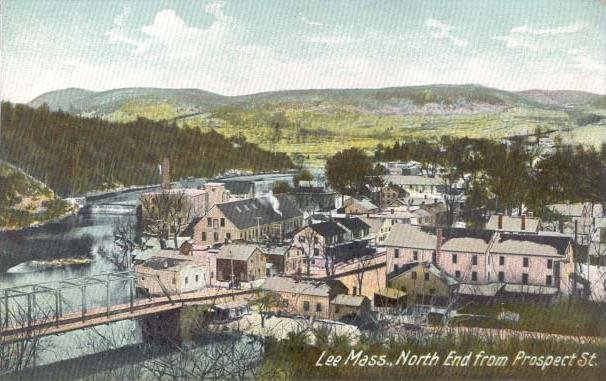

Lee, Mass., in The Berkshires, is everyone’s vision of a typical New England town. The Main Street is short and to the point. Buildings, unmolested by town planners, have maintained their character throughout the years. The house where we bunked for several days dates from the 19th Century and has been well kept by its owner, an engineer who had, like Odysseus, moved about in the world. He was born, very likely in or near the house we occupied, moved with his family to Washington, D.C., where his father had found a job that he could not refuse as an electrical engineer, and later back to Lee.

The firehouse across the street from Garfield House, where we stayed, is a solid stone structure that boasts a square steeple that one easily might mistake for a bell tower or a medieval watch tower.

Traveling around New England, one must – delicately, delicately – approach the topic of politics. Open wounds are everywhere. Much of New England is solid ultramarine blue (there are dramatic exceptions, such as Aroostook County, Maine). That is to say that many people in New England wish to see former Donald Trump in leg irons waltzing through a prison yard. My wife, Andrée, believes that such emotions are far too enthusiastic. She taught American Studies for many years and is intimately familiar with the religious enthusiasms of the 17th Century that saw a witch behind every bush.

Trump, she likes to say when not in the presence of people still suffering political whiplash from the 2016 Hillary Clinton/Donald Trump campaign, is, in some respects, a man more sinned against than sinning, though, of course, she would never say such things in the presence of those who wish to burn Trump at the stake – which is to say, in a good deal of New England. Consider that Democrats in Connecticut, a part of New England and our home state, outnumber Republicans by a two-to-one margin, with unaffiliateds topping Democrats by a small number.

Andrée laid down the law long ago: There will be no politics spoiling our vacations. This law of the household precedes Trump’s ascendency to the presidency by, say, a half century or more. No politics means no computers, no cell phones, no newspapers, no furtive notes written in the shadows, and only mercifully brief encounters with witch-burners.

“Just change the subject, will you?”

In very few places throughout the world -- Washington, D.C., of course, other uncivilized places that used to be part of the British Empire, including most of New England, and Italy— everywhere and always – political talk with strangers destroys the moment, and living in the moment is essential to travel. In Florence, Italy, we almost missed, through dreamy inattention, the spot where Savonarola had been burned at the stake. It is a grave sin to have eyes and not see, ears and not hear, when traveling about the world.

Just ask Odysseus, a victim of enchantment and forgetfulness during the year he spent, not unpleasantly, with Circe. First, the traveler forgets where he is, then who he is, and then the once-solid world dissolves like a dream.

“Pay attention!”

It was no chore for us to pay attention to Herman Melville, most famous, of course, as the author of Moby Dick. In college, he was our literary touchstone. One day, early in our marriage, I brought home a little-read book by Melville, Pierre or the Ambiguities. It’s a romance novel, and Andrée, an incurable romantic, fell for it head over heels. A little later, though we already had been married a couple of years, she fell for me, not quite head over heels.

We had visited Arrowhead, Melville’s home in Pittsfield, years earlier when the house was in transition. No one was home, the house, garnet-red at the time, was dark and forbidding and vacant. Even the spirit of the place had taken flight. We peeked in the windows. Off in the background, Mt. Greylock, the highest elevation in Massachusetts, showed his hump.

Melville wrote Moby Dick in this house. He dedicated the book to his good friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, then living part time in nearby Lenox. The book following Moby Dick, Pierre or the Ambiguities, was dedicated as follows: “'To Greylock's Most Excellent Majesty ... the majestic mountain, Greylock — my own more immediate sovereign lord and king — hath now, for innumerable ages, been the one grand dedicatee of the earliest rays of all the Berkshire mornings, I know not how his Imperial Purple Majesty ... will receive the dedication of my own poor solitary ray ...''

Greylock, we found, was full of winding ways, but so was Melville’s route through a tortuous world. Moby Dick, now considered a classic American novel, was a conspicuous failure in its day. And it was only after Melville had died that the book rose from its deadening reviews.

Today, as always, the book must be read aloud, not so much with the eye as with the ear of the heart. It is music to the ear and, like all music, it winds its way over long Shakespearian passages, moving gracefully at its own pace. It was this music that had enchanted Andrée so many years ago.

The trip to Arrowhead reminded me that traveling is an inward experience, not merely a collection of interesting photos taken of interesting places along the way.

Mark Twain, a Connecticut resident for many years, traveled widely in Europe. And partly on the basis of that, he wrote a little-read book he considered his best: “I like Joan of Arc best of all my books… It furnished me seven times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others; twelve years of preparation, and two years of writing. The others needed no preparation and got none.” (The full name of the novel is Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc.)

Twain was anti-clerical, not necessarily anti-religious. But the character of Joan, buried for many years under heaps of anti-Catholic perfidy, was paramount for Twain: “Taking into account…all the circumstances—her origin, youth, sex, illiteracy, early environment, and the obstructing conditions under which she exploited her high gifts and made her conquests in the field and before the courts that tried her for her life—she is easily and by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.”

The Mount, novelist Edith Wharton’s plush estate in Lenox, is only a 10-minute ride from Garfield House.

There’s a picture on one wall in the estate’s mansion of a salon gathering in which Henry James makes an appearance. Anything Jamesian is redemptive for Andrée. As an American Studies and American Literature teacher for many years, both in Catholic and public schools, she taught James and other famed authors to students who eventually came to appreciate James’s long winding prose paths – very Shakespearian and even Melvillean.

Twain was not a James fancier: “Once you put him down, you can’t pick him up again.”

But Andrée likes the winding ways of a strong – dare I say it? -- Faulknerian sentence, very much like the path the imagination takes when it is called into service in our travels.

Our next-door neighbor at Garfield House, a permanent resident and an expat from New York, told us that she had lived for a time in Wharton’s reading room while she was an administrator of the Shakespearian Company that put on plays at The Mount.

“You were an actress?”

“Oh, God no, please no – not an actress. I worked behind the scenes as an administrator to put on the plays.”

“In New York?”

“Yes. New York had become too cloying, so I came here, fell in love with the place and stayed. By the way, you told me that you like golf, but you do not like golfers. Just a word to the wise: You had better not say that to the proprietor of Garfield House, who is an avid golfer.”

I agreed, as Andrée said, to “change to subject” if it came round to golf.

Golf, like politics in New England, has become in recent days a secular religion full of saints and heretics – none of them, unfortunately, quite like St. Joan of Arc.

Twain on politics: “In religion and politics people’s beliefs and convictions are in almost every case gotten at second-hand, and without examination, from authorities who have not themselves examined the questions at issue but have taken them at second-hand from other non-examiners, whose opinions about them were not worth a brass farthing.”

Now there, Andrée might say, is a near perfect Jamseian sentence, very much like the hiker’s paths that cross and re-cross Mount Greylock. Our very last adventure before leaving Lee for home was to ride – not walk – to the top of Melville’s “sovereign lord and king.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn., based columnist.

Front Entrance of The Mount.

— Photo by Margaret Helminska

1907 postcard.

Don Pesci: From a contrarian's journal

Andree, Don and Dublin

February 2022

It may be time for me to explain, if only to myself, what I think I have been about.

__________________

I woke up this morning thinking: Why should we not confess our joys as well as our sins?

Today, Feb. 6, 2022, is full of sunshine, following three or four days of gray skies. It snowed several days ago. This was followed by a light rain, followed by a freezing rain – very inconvenient. It is not the hammer blows of despair, but rather the water torture of inconvenience that, in the post-modern world, drive men to murder and mayhem.

The morning sun is burning brilliantly on what is left of the snow, Andree is snug in her bed – glad I was able to warm her, since I usually wake at about 7:30 and descend the stairs to write a column I suspect no one will print – and it seems just now, as Professor Pangloss often says in Voltaire’s Candide, “the best of all possible worlds.”

God is in his heaven and, while the world sleeps, politicians in Connecticut are plotting their campaigns. The snow and rain, unlike journalistic reports, fall indiscriminately on both the just and the unjust.

__________

Within the journalism “community”, everyone has become Candide, a victim of optimism crushed by a real-world pessimism and a kind of pretentious, wild-haired and goggle-eyed cynicism.

And hasn’t the “community” business has gone a bit too far? There is such a multiplicity of communities that it seems mankind can never gather joyfully under a common flag. We used to speak of families, of neighborhoods, of towns, of states, of nations. Now all the talk is of artificial, hastily assembled “communities.” Yesterday, someone mentioned the “academic community,” another the “felon community,” and I couldn’t help but wonder whether there is any important difference between the two.

___________

You wonder, my friend, why suddenly I have taken an interest in numbers.

Simple, “I am old, I am old; I wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled,’’ a T.S. Eliot wrote in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’’.

On July 15, 2021 the day following Bastille Day, I turned 78. After 65, numbers become inordinately important. You begin counting down the days and realize, with something of a shock, that all our days are numbered – and always have been -- whichever community we may belong to. There is no salvation in belonging to the academic community or the journalistic community, both swollen with what Jacques Maritain used to call “practical atheists,” people we might call cultural Christians and Jews, which is to say people who do not take either Christianity or Judaism seriously but wish merely to dress up in castoff robes so that, as Mathew 23:5 has it, they may be seen of men: “And they do all their deeds in order to be seen by men. For they broaden their phylacteries and enlarge their tassels,” a nearly perfect description of the twittering class.

Years ago someone inadvertently put the biblical injunction into a Louis Prima song -- “Just a Gigolo.”

I'm just a gigolo and everywhere I go

People know the part, I'm playin'

Paid for every dance, sellin' each romance

Ooh, what they're sayin'

There will come a day, and youth will pass away

What'll they say about me?

When the end comes, I know they'll say -- just a gigolo

And life goes on without me

Incumbent politicians of long standing in Connecticut and elsewhere, political gigolos, know how to twitterize and tasselate the crowds.

We have in Connecticut two prominent Catholics in the all-Democrat U.S. congressional delegation who, in respect of their church’s position on abortion, are heterodox. U.S Representatives John Larson and Rosa DeLauro are abortion enthusiasts, like U.S. Sen. Dick Blumenthal. Blumenthal’s present position on abortion – never under any circumstances should the practice be regulated – might have scandalized then President Bill Clinton in 1993, a pro-abortion visionary who said, "Our vision should be of an America where abortion is safe and legal but rare.”

Post-modern progressives, now in charge of the Democratic Party’s ship of state, like their abortion well-done – indeed, overdone. That is the chief problem with progressives: Whatever they do, they overdo. If progressives were a majority of chefs in restaurants in Connecticut, rare steaks would become a rarity. On the question of abortion alone, progressives are culturally libertarian. Otherwise, they are far left-of-center socialists or Gramsci Marxists.

____________

My nieces and nephews will have no personal memory of grandfather Carlo The Fox. He passed, as people who sidestep the word “died” say, before their time. He has no standing in their memories.

But I remember him coming and going to the homestead at 1 Suffield St., Windsor Locks, Conn. He used to stop by during his peregrinations every so often to touch base with my mother, the only person in the Mandrola family he could not frighten.

The Rose who stole my father's heart

One day he came by with a bunch of flowers and a handful of bills, both of which he shoved at Rose Pesci the indomitable. Giving dollars away – and so many dollars – struck her as out of character for “The Old Man,” an affectionate term within the family.

She was bewildered.

“What’s this?”

Carlo told her, in his somewhat broken English, that he was giving her money to purchase some flowers when he… umm … passed on. He did not want the funeral parlor to be bare of flowers. And, really, there was no one else to see to it but her.

She once told me, “Your grandfather had a green thumb. He could make roses grown from rocks, and not roses alone, but any green thing.” She said she would see to the flowers.

Carlo moved on towards Bianchi’s restaurant for another coffee-royal and, later in the day, a light lunch. One of his stops was the A&P on Main Street, where he usually bought a steak to be prepared for him in the afternoon by Armando Bianchi, the proprietor of the restaurant. The Windsor Locks Main Street was a casualty of a “redevelopment” scheme that began during the silly 1960s and ended with an antiseptic Main Street, new and useless after all the merchants had been displaced, their places of business lost to “redevelopment.”

The redevelopment plan, still in process in year 2022, was an idea that burned hotly in the indifferent brains of the “redevelopment community.” The idea was to sweep aside the entire Main Street and rebuild it anew from the ground up. It was not buildings but histories and memories that were plowed under, never again to see the light of day. When everything had been leveled, Windsor Locks looked somewhat like Sodom on the day following its God inspired destruction.

There were lots of flowers at Carlo’s wake.

Most of my boyhood past is gone now. I am visited from time to time by pale, ghostly memories stripped of flesh and blood.

The future, naturally, has become a Thermopylae pass, narrow, pinched, but still worth defending, even at the cost of one’s life and fortune: “Go tell the Spartans, stranger passing by, that here, obedient to their laws, we lie."

_____________

March 2022

The voice of a Blumenthal suppliant -- most reporters in the state -- shouts in my ear: “You numbskull, can’t you see? Our enlightened Senator Dick Blumenthal believes he need not listen to the people to know what is best for them, the dirge of the postmodern progressive afflatus.

Blumenthal, whose approval rating in the state has unaccountably plummeted for the first time in his long political career, is rich in money and purloined knowledge. Harvard, Yale and an auspicious marriage have blessed him with an abundance of riches. He claims to know what is best for the poor, without having gone through the trouble of living cheek by jowl with the poor unfortunates. It is much safer to view the apparent cultural anarchy of urban life in Connecticut from a Greenwich, Conn., safe house. There is little doubt that alms, furnished by Blumenthal and his sort from the public treasury, a down payment on future votes, are best for him.

For the politician who knows how to help voters help himself, the solutions to poverty are best when they are other directed and permanent rather than passing. That is the beginning and end of the moral acuity of postmodern progressives.

And if God does not exist, the central belief of practical atheists, well then Blumenthal is perfectly willing to step into the absent landlord’s empty shoes. The media has not painted a halo round the senator’s head for nothing. Half the troubles in the world arise from voters inattentive to Psalm 146:4:

Praise the LORD, O My Soul… Put not your trust in princes, in mortal man, who cannot save. When his spirit departs, he returns to the ground; on that very day his plans perish. Blessed is he whose help is the God of Jacob, whose hope is in the lord his God.

This Psalm, ascribed to King David or Solomon, first entered the rich Jewish literary canon during or after the Babylonian captivity and the subsequent liberation of God’s people. If this is cynicism, it is prophetic cynicism.

The cynic’s eye is the jeweler’s eye that sees without distortion the difference between good deeds and the pretense of good deeds. What the poor really lack is independence and self-sufficiency. The poorest man is not the one who is temporarily incapable of helping himself or his family, but the man permanently incapable of helping both himself and the stranger among us.

__________

Mark Twain, certainly more quotable that the average post-modern politician, said about New England weather, “If you don’t like it, wait a minute, it will change.”

This past April, the whole of New England was caught in a violent rain and wind storm -- sleepless nights, the rude, rough wind banging on our windows.

Dublin, Andree’s guide dog, slept through most of it and was triggered only twice. When Andree took him out in the early morning, gray and forlorn, the wind was still shaving dead branches off the trees. I battened down the tarp covering our wood pile, removed a few fallen branches, and headed off to Lance – great first name! – the eye doctor, who was pleased to note that the pressure in my right eye had been satisfactorily reduced from 33 to 11.

“Exactly where we want it,” he said. “We already have a blind wife in the family. We don’t need a blind husband.”

Could I discontinue the use of the eye drops he prescribed a couple of weeks ago?

“Well… no.”

“How long must I use them?”

“Pretty much forever.”

When I arrived home with the good/bad news, I saw two pileated woodpeckers doing what woodpeckers do, debarking a tree, both bathed in early morning sunlight, a red stripe marking the male’s bridge between beak and crimson crown. Pileateds, executioners of carpenter ants, fly to New England this time of year from Florida, where at least a half dozen of my neighbors, lashed by winds, wished they were just now.

A storm last year sheared off the top of a large oak tree fronting the street. There it stands now, a pillar of oak, a mere suggestion of a tree, its top open to the elements, a haven for carpenter ants. I thought to direct the pileateds to the meal but realized that, like state contractors, they were not always open to creative suggestions.

Our grandfather clock, with us for decades, has been cleaned and fixed. It was last cleaned by an old septuagenarian clockmaker several years ago. The current clockmaker is a young man, sprightly, full of opinions he is happy to share at the drop of a hat, and just a wee bit off kilter, both Andree and I agree, a compliment rather than a criticism. Tedious people are on-kilter most of their lives. And when they come to die, they discover they had only begun to live three minutes before passing on.

The current clockmaker will not feel his life had been wasted when the devils or angels come to drag him up or down. I have no idea which way he is headed.

He seems religious – not, thank God, “spiritual” -- as some people are these days.

The “practical atheists” scorned by Jacques Maritain are spiritual wastelands. St. Francis of Assisi, who appeared naked before his bishop after he had surrendered to Christ and given up unprofitable ways, along with his substantial fortune, was religious rather than spiritual.

One cannot imagine Senator Blumenthal waving farewell to his vast stores of wealth in this way, though he seems to have had little difficulty over the years as state attorney general persuading the moral mob to despoil his neighbors.

“I have become a socialist,” Perrot cries out in Edna St. Vincent Millay’s play, Aria DeCapo. “I love mankind – but I HATE! people.”

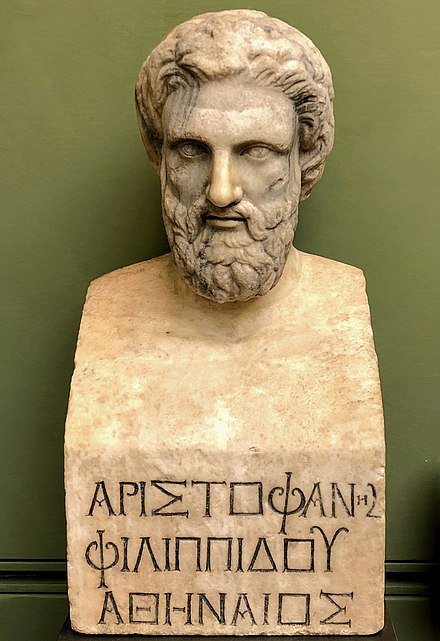

Our clockmaker does not hate people. He is amused by them, always a sign of mental stability. The comic playwright Aristophanes, writing during the Peloponnesian War, was possibly the sanest man in all of Greece. Agents of a powerful puffball he had been lampooning in his plays, Creon, stopped him on the street and asked imperiously, “Don’t you take anything seriously?” to which he replied, “Yes, I take comedy seriously.”

I tell him the story of Jonathan Swift’s missionary in Africa whose flock thought that his watch was his God, because he consulted it so often.

The clockmaker is young – but then, everyone under 65 seems young to me – and convivial. “You’re welcome to stay here and talk to me while I clean the clock,” he said. “I like talk. It passes the time.”

Dublin, holed up in the bedroom, was barking but stopped after a while.

Andrée explained that Dublin was a Fidelco guide dog. He came into our household after her previous guide dog, the mighty Titan, died, leaving her bereft and in tears for days.

Before her first guide dog, Jake, came to us, almost on Christmas Day more than 20 years ago, she had little commerce with any domestic animals, owing to her mother’s fear that dogs and cats might sully a clean and spotless house. Her mother, Margaret Descheneaux, was all of her life pure of heart, mind and hand.

Jake was Andrée’s first encounter with nature in the rough, though he was, of course, highly trained. He was a large dog, nearly 90 pounds, regal, indifferent to me – which we both appreciated – and fiercely loyal to Andrée. He lived to be about 14, all of his years a blessing to Andrée, who is, if such a thing can be imagined, as fiercely loyal to friends and family as Jake was to her. Naturally, a stickler on such things as “thank you” notes, she expects her affections to be unselfishly recompensed.

The two, a woman and her dog, also had in common a joy of life, a healthy intolerance of profound stupidity – in the age of Google, no one any longer can lay claim to innocent ignorance – and a brilliant intellect, as well as a fully functioning, inerrant intuition. Dogs are intuitive, anticipatory animals, and Andrée is now convinced that German Shepherds are the lion-kings of dogs.

Titan is in black, Jake dusted with gray at 13.

Mark Twain, incidentally, felt the same way about dogs: “The more I learn about people, the more I like my dog.”

One wonders, did Homer have a dog? Did Dante or Milton? What of Shakespeare? Google is silent on the necessary connection between dogs and poetry, so we may assume a connection, an assumption that takes no great leap of the imagination. The mistreatment of a horse brought Nietzsche to tears. T.S. Eliot’s connection with cats is well known. Surely, some bubble-enclosed, monkish academic has researched the question, yet academia remains unaccountably silent.

Jake died more than 14 years ago, noble and valiant to the end.

When we arrived home 3:00 in the morning from a trip to Arizona, we found posted on the door a note that said, “Go to the vets immediately,” this written by friends with whom we had left Jake.

The vet led us to a metal table cushioned with a towel where Jake was stretched out breathing softly. He had been there for a dozen hours – waiting, I believe, for the touch of Andree’s hand. She leaned over him, breathed into his ear a message I could not hear, and then he left us.

Titan came to us two years before Jake died, his body a shining ebony unmarred by a single spike of grey hair when he died at 14.

Bill Buckley asked me once, “Do you suppose there are dogs in Heaven?” My answer, stupidly sophistic – maybe doggyness exists in Heaven – failed to satisfy him, because he was hoping that he might encounter on the other side of the pearly gates the dog he loved when he was a boy.

Why must love and beauty die? Do they die? Is not beauty the face of God that even Moses was not privileged to see?

“You cannot see my face, for no one may see me and live."

_____________

U.S. Senator from Connecticut Dick Blumenthal gave up thinking for himself about midway through his 20 year stretch as attorney general. He found it more convenient to let others, the 200-plus lawyers in the attorney general’s office, think and do for him. Naturally, he was always available to take credit for the wins and write off the losses, few in number, as a predictable consequence of righteous action.

The front line troops in the office all were eager to do the bidding of their boss. Perhaps they too in the future might become attorney general, at which point they too might luxuriate in the soft media glow produced by eager-to-please journalists. So all-surrounding is media adulation of Blumenthal, that he cast no shadow.

The trick in both politics and business is to get others to do your work for you, on condition that the worker retires into the woodwork and allow you to reap the glory. Months and years of this sort of thing blunts the brain and makes Jack a dull boy.

Blumenthal looks like a Harvard/Yale graduated pedant, and an unruffled multimillionaire, both of which he is. Some are born pedants, some achieve pedantry, and others have pedantry thrust upon them. This persona is one Blumenthal has chosen for himself.

Blumenthal never has had an ardent and effective political opponent. His more promising Republican Party opponents have been driven from the field by money or a media adoration approaching worship.

Blumenthal drifted into the U.S. Senate, as did Senator and stated Attorney General Joe Lieberman before him. The path to glory from the Connecticut attorney general’s office to the U.S Senate is a well-worn one. This red carpet has deep grooves in it.

If some political-psychologist were to lay Blumenthal on his couch and do a deep dive into his political persona, he would uncover a frightening vacuity, all polished surfaces but no depth -- pedantry perfected.

Less accomplished political pedants, President Joe Biden comes to mind, might well be jealous. Biden is such an unoriginal thinker that he must borrow from others to rise to the level of pedantry. He has been caught plagiarizing a few times by journalists in forgiving moods who now find his inattention to detail amusing or endearing.

Plagiarism and pedantry go hand in hand.

To give but one example: Blumenthal’s position on abortion, unoriginal and self-contradictory, has been lifted from Planned Parenthood, which is why I have referred to him several times as “the Senator from Planned Parenthood.”

His position on abortion is the same as that of any chief executive officer of a large, profitable enterprise -- no impediment should get in the way of the business we support.

With regard to their own big businesses, CEOs are libertarians, shouting from the rooftops their adulation of freedom and liberty. In respect to their competitors, they are executioners very much in need of bought politicians who, their hands having been greased with campaign donations, may assist them in reordering the free market to their advantage, for the most closely guarded secret among clever big business “free marketers” is that politicians may be called upon to help them crush their creative and inventive competitors.

I sometimes think of Hilaire Belloc’s “Advice to the Rich” in connection with Blumenthal: “Get to know something about the internal combustion engine, and remember – soon you will die.” Blumenthal, one may be certain, knows far less about the internal combustion engine than his chauffeur. As to the free market – are we not all Keynesians now?

Blumenthal’s cadaverous aspect – Is he a biker? -- fairly screams, “I will live forever!”

A Democratic Party political hack, he and Biden are pretty much on the same page politically concerning the necessity to end fossil fuel as an energy source, as soon as inconveniently possible. As attorney general of Connecticut for two decades, Blumenthal was accomplished in shutting down small businesses, easy political targets, and extorting campaign funding from large businesses. His long tenure in Connecticut politics suggests that the prospect of death and a final reckoning still lies, God willing, very far in the future.

_____________

July 2022

How is it possible that the establishment media in Connecticut so infrequently reports the obvious? During his basement campaign for the presidency, Biden, one eye cocked on pseudo-anarchists such as Alexandria Ocasio Cortez and her “Squad”, pledged to do away with fossil fuel. He abandoned a nearly completed pipeline and reduced the possibility of supply -- a surety of his pledge. It worked. In no time at all, gas at the pump being in short supply, the price of gas rose from a low during the Trump regime of $2.96 in May 2018 to its present level, a brain rattling $4.84 per gallon. In concert with high energy prices, increased costs in the price of goods and services, owing largely to exorbitant spending, a historic rise in inflation, rhetorical buffoonery some ascribe to mental deterioration, and a pending recession, Biden’s approval rating has dropped to 38 percent, and “an early June poll from Ipsos/ABC News found that only 28 percent of Americans approved of Biden’s handling of inflation; along with his handling of gas prices (27 percent approved), inflation ranked lowest of any of the issues the poll asked about.”

See Biden, Lamont, Connecticut Democrats – Meet Gresham’s Law.

_______________________

We are off today to visit my cousin Bill Mandrola, at his son’s house in Suffield, Conn. Anthony and Amy Mandrola have moved from Los Angeles. Bill and all the first-family Mandrolas – two daughters of Carlo the Fox and four sons -- lived for many years in the homestead on Center Street, Windsor Locks, before he and his wife migrated to Arizona, after he had retired from a prominent Hartford insurance company.

My brother Jim, who worked for many years at Travelers Insurance Co. – bumped, as was my father, after the company had been mismanaged for years by an inept CEO – moved to Columbia, S.C., his son, David, following in his father’s footsteps a few years later. David and his wife, Corin, moved to North Carolina.

These moves I regard as the Great Unmooring. Somewhat like a shipwrecked Ishmael, I , not quite alone, am left in Connecticut “to tell the tale.”

And what a tale it is, part of it told by Bill in a personal memoir, Dampadog, Johnny Mandrola, Storyteller. My uncle John, Bill’s father, is the storyteller of the memoir.

The Mandrolas are suburb storytellers. Family stories are, in part, factual accounts graced with what Mark Twain used to call “stretchers.” The purpose of a stretcher, not in the least a distorting conscious lie, is to emphasize the truth of an event. One cannot trust memory to preserve the integrity of important, life shaping events. The memory is refined – corrected, amended -- always in the telling. And, of course, in the case of Italian families, some things are better left unsaid. But over the supper table, nothing is left unsaid.

My mother rarely left anything unsaid. If you asked her for the truth or not, you would get it.

Bill, an inveterate traveler, wears his age well. The kitchen table at Anthony and Amy’s house was well laid with antipasto – some hard cheese, Soppressata, shaved Genoa, crackers that crunched in your mouth, wine – always wine – and company. What begins in the kitchen never stays in the kitchen of an Italian household, and this includes stories told and retold, until they are as smooth in the telling of them as stones in a brook, polished and glowing beneath the flowing water.

Stories were told about the two first families, the Mandrolas and the Pescis, the Windsor Locks Canal, a swimming hole with a dangerous undertow before my father Frank, the town’s first park commissioner, put a pool in Pesci Park, visited by all on sun-drenched summer days, the nuns of Saint Mary’s parochial school, now a refurbished apartment building, Carlo’s, as it seemed to us, irrational fear of nuns, Marconi’s soda shop on Main Street, friendly idiots, unfriendly antagonists.

My sister: The Pertusi brothers, John and Anthony, came to visit us on Christmas, and other times as well. John Pertusi cornered Carlo on the Pesci porch and began, in his usual manner, to philosophize and gush over nature. Flowers were beautiful, the skies of New England, God’s blue fingerprint, were especially beautiful… and so on and so on. Carlo listened to him patiently, smiling his usual inscrutable smile, until John struck a nerve with a question. What do you think happens to us after we die?

Carlo: The worms get you.

Anthony, Bill’s son: I like the way you talk about Nellie, his grandmother.

Me: When I was small, very small, I told my mother one day that I was dissatisfied with her treatment of me. I wanted to go and live with Nellie and John on Center Street. She never hesitated a moment. Okay. She packed a small cardboard suitcase, and I was away down the stairs, where I met Carlo, returning home from Bianchi’s restaurant.

Carlo’s habits were almost mechanical, like the works of a grandfather clock, and unvarying. He was, I thought, on his way home from Bianchi’s.

Someone else: Every day, he’d go to the A&P on Main Street, buy a slab of meat, hang out at Bianchi’s with his friends, drinking and playing cards, eat a light lunch, then return up Suffield Street on his way back home to Center Street.

Me: He found me on the sidewalk and asked in his broken English, studying my suitcase, “Where you go?”

I told him I was going to live with Nellie and John. So, he took my hand and led me to my preferred home. Nellie loved me. She had taken care of me when I was a small baby. The Mandrola homestead was for me Eden without the serpent, a paradise of roses and cherry trees, and Nellie’s meals, cooked always the way I liked them. But at that age I used to walk in my sleep. And thinking I was on my way to the bathroom, I fell down the stairs. I woke the whole house with my wailing, but I was unhurt. Nellie put me back to bed. At the touch of her hand, I fell asleep. Of course, everyone understood that nothing of this was to be mentioned to my mother. However, I suspected that she knew every detail. She and Nellie were fast friends, and there could be no secrets between friends. When I returned home, my subdued mother was, I liked to imagine, properly chastened.

Bill’s Ponzi story: “He was a bit,” hesitatingly, “fussy.”

Fussy? Ponzi was a hypochondriac.

Ponzi and Dampadog made friends with a woman, widowed, who owned a house on a fish-filled pond near Stony Brook. They wanted to use her boat to catch bullheads, the pond’s bottom feeders. Ponzi was in the front of the boat, my father in the back. And Ponzi was catching fish after fish, my father nothing – very distressing. So when Ponzi passed the line to my father to bait his hook, he clipped the line, leaving only the sinkers to tempt the bullheads. But they were not biting sinkers that day. And my father began to catch all the fish, Ponzi nothing. After the catch had evened, my father said, “I think the pond has been overfished. Let’s go.” But the wondrous thing about all my father’s stories were – they had no endings. The narrative was just left there for you, tempting, dangling, unfinished….

Like those succulent apples – “experts” now have told us they may have been pomegranates – in the Garden of Eden. God, when all is said and done, is the author of final things. We poor mortals can only aspire to be honest recorders of the beginning and middle of things.

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based columnist.

Don Pesci: Chatting with Aristophanes about comedy

Bust of Aristophanes (First Century A.D.)

The Theater of Dionysus, Athens . In the time of comic playwright and poet Aristophanes (446-386, B.C.) the audience probably sat on wooden benches with earth foundations.

VERNON, Conn.

Q: It’s so good to meet you (chuckles) in person, so to speak.

Aristophanes: Funny. Would you mind if I use that in the future?

Q: I wasn’t aware there was a future for the dead.

A: That is what I might call an example of the arrogance of the living. You are forgetting William Faulkner, who said, "The past is never dead. It's not even past." He wrote most persuasively about the past by resurrecting the dead in his novels. We all do that, in one way or another. You must remember that the only advantage those who are alive at present have over the dead is that they are alive and the dead are dead. That’s it.

Q: I wonder if you can confirm a story about you, not that it has anything to do with the subject of our discussion, the role of comedy in culture. It is said that you died from a falling roof tile that struck you on the head. One of our commentators said your manner of death was ironically appropriate, for a comic writer.

A: (nonplussed, a vacant look)

Q: He was making a joke.

A: Ah, yes, I get it. And you want to know if the joke is true?

Q: Yes.

A: Well, jokes are always true. But how can I tell you that the incident happened if I had been struck dead by a falling roof tile? Besides, if you have done even minimal research on me – a quick glance at what I call Wickedpedia – you will know that little is known of me? I managed to keep myself well hidden in the plays. Your age is obsessed with facts, but it is important to understand that facts, provided they are all accounted for, are vehicles that may lead to truth. But, in some instances, fiction serves the same purpose, which is why we do not dismiss Shakespeare and Faulkner as unimportant.

Q: It’s Wikipedia, by the way.

A: Not when you are punning.

Q: One of the purposes of this interview is to gather comments from the real Aristophanes about the real world.

A: From what I know of your time and world, I’m not sure (very condescendingly) you people understand either reality or your time in it. And being introduced to your world is a frightening prospect for anyone but a comic writer, provided he is allowed to ventilate his opinions. All comedy is what the moderns call transgressive, and all comedians are at bottom contrarians. Think of “the fool” in Shakespeare’s plays. A real take on your real world would reduce Euripides to tears and make Socrates blush -- and, believe me, Socrates was not given to blushing or Euripides to weeping.

Q: I should ask you, since you and other dramatists were the journalists of your day, do you think, as a general rule, that journalists also should be contrarians?

A: I do. So did Joseph Pulitzer and H.L. Mencken.

Q: I’m guessing the tyrant Creon was cool to your plays in which he was, some say, mercilessly caricatured.

A: In the Athenian republic of my day, it was understood that comics, the Shakespearian “fools” of Greece, should be permitted to dress down world saviors. After Sparta defeated Athens at the close of the Peloponnesian War, comic writers became considerably more cautious – for obvious reasons. As you may have guessed from a close reading of Lysistrata, I was in favor of what Henry Kissinger might have called an Athenian “diplomatic entente,” rather than a 26-year war with Sparta. Actually, Sparta’s peace terms were far less draconian than the terms imposed by World War I’s victors on a humiliated Germany. Sparta won the war, but Athens won the peace, nothing short of a miracle. Old Comedy became a more politically genteel New Comedy after the war, and the New Comedy was less wearing on the nerves of tyrants the world over. Your situation is similar. You have in your country the same fixation with world saviors – naturally, all of them Americans. In a regime of authoritarians -- or, worse, experts -- comedy is rarely tolerated, because comedy is an attempt to readjust proper proportions. When things are out of shape, the comic is the person who whacks them, by means of his comedy, back into shape. It is impossible to imagine in Russia, for instance, a roast of Putin. When I was approached on the street by one of Creon’s lackeys who demanded, “Don’t you take anything seriously?” I responded, as any good comic should, “Of course, I take comedy seriously.” After Athens’s defeat by Sparta at the decisive Battle of Aegospotami, such responses became less advisable and comic wit suffered grievous indignities. Fortunately, I lived to see the revival of Athens after its crushing defeat by the Spartan General Lysander in 405 B.C. Creon wanted a war to the finish with Sparta – and he got one.

Q: Naturally we care more about our present than your past, despite what has been said by Faulkner. But what riches can you bring to our reality?

A: The French, who can be amusing if you catch them in a nonpolitical mood, say – a poor translation – “the more things change, the more they remain the same.” You are now in the process of scourging your comedians. It will not be long before you hoist them on a cross. Here is some advice worth something: comedy is the canary in the cultural mineshaft. And a poisonous culture will repress comedy first, and everyone else later, simply bury them under mounds of humorless, pretentious group-think. Just before the Hungarian revolt, a worker slated by Karl Marx as the future owner of the means of production was asked to comment on his condition under the Marxist-Leninist dispensation. “They pretend to pay us,” he said, “and we pretend to work.” That man understood the proper use of comedy.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

The Tower on Fox Hill in Henry Park, Vernon

Don Pesci: In Arles: ‘We will take you’ to our ‘Gold Coast’

Aerial view of Arles. Note the Roman arena.

— Photo by Chensiyuan

VERNON, Conn.

Whenever French President Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron comes to mind, more often than I would wish, my remembrance floats back to a conversation we had with François, a boat owner in Arles more French than the Eiffel Tower and more emblematic of France than Macron.

François’s boat was parked on the Rhone just below our larger boat. My wife Andrée and I were leaning over the rail, about to descend on Arles, when he called up to us in communicable English.

“Where are you from? You are American.”

“Connecticut. This is my wife, Andrée.”

“Ah, French!”

“Her father was from Trois-Rivières, Quebec. She has Indian blood in her. The French and the Indians were on amicable terms, you may recall.”

“Yes.”

He would have said “yes” in any case, because he was in the process of selling his boat.

“Americans are rich, eh?”

“Not us,” my wife responded in French. “We’ve escaped that torture.”

François laughed, a hearty boatman’s laugh, no guile in it at all.

“You should come down here. I’d like to sell my boat to you.”

We declined the offer, but joined him on the dock where his boat was berthed. He brought us some wine and cheese from his boat.

“In Connecticut,” Andrée said, once again in French, “you are right to suspect that all the roads are paved with gold, especially in Fairfield County, where I was born and raised. This is the ‘Gold Coast’ of Connecticut, but we have no gold in our pockets to buy your beautiful boat.”

The boatman’s eyes glowed. Here was a woman who understood him.

“I will show you Arles.”

And he did.

When we left him, Andrée said to François, “You have been so kind to us. If ever you come to Connecticut, you must find us.” She gave him our address. “And when you come, we will take you to Fairfield {County}, where there are many rich people and many yachts. The people there would be interested in buying your beautiful boat.”

The three of us knew that we would never see each other again. Some kindnesses must remain unpaid. He lifted her slim fingers to his lips and we said our farewell to Arles.

Later that night, bunking in our own boat, traveling south on the Rhone through Provence to Nice, Andrée said, “I can still smell the wine of the region on my hand.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Waveny Mansion, in New Canaan, in the “Gold Coast’’ of Fairfield County, Conn.

— Photo by Karl Thomas Moore

Don Pesci: 'Tax relief' and 'tax cuts' on shifting sand

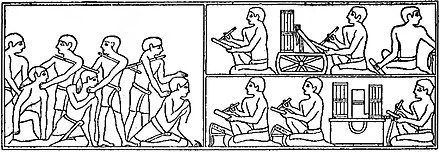

Egyptian peasants seized for non-payment of taxes several thousand years ago.

VERNON, Conn.

“The future ain’t what it used to be”

– Yogi Berra

The headline in a CTMirror story, “CT budget deal includes $600M in tax cuts, extends gas tax holiday”, includes a telling subtitle: “But more than half the tax relief is guaranteed for just one year.

There’s always a “but” in good journalism raining on someone’s parade.

The thrust of the story raises an interesting question: In what sense is “tax relief” a “tax cut”?

Many of the “tax cuts” referenced in this and other stories in Connecticut’s media are either temporary tax cuts or tax credits.

A temporary tax cut is only a “tax cut” until it elapses, after which it becomes once again a tax increase. And a “tax credit” is not, properly speaking, a tax cut. A tax, almost always permanent, moves money from a taxpayer’s budget to a state or federal treasury. A “tax cut” terminates the movement and leaves disposable assets in the account of the taxpayer.

A tax credit retains in public treasuries money moved from private to public accounts and surrenders a small part of the tax money collected to favored taxpayers.

From the point of view of the tax collector -- the state or federal government -- the beauty of a tax credit lies in the generally false appearance that those extending the credit are surrendering to preferred groups money that has been earned by state or federal government.

In moments of extreme clarity, everyone knows that a state government does not “earn” money of its own, as do private enterprises by producing and selling goods and services. States are tax collectors only, and the money they apportion belongs to tax payers who, through their own labor, earned their assets. Naturally, those surrendering money to state or federal government would like to believe political claims that the money collected would be used by government to increase the “public good.”

That is why the headline writer for CTMirror felt compelled to add to the story that clearly identifies what state Democrats and some media adepts consistently call “tax cuts” a subtitle that identifies the so called “tax cuts” as “tax relief.” A true tax cut eschews collection and leaves assets to be disposed of by a creative, enterprising and profit-seeking private marketplace. A tax credit reduces all three elements – minus a small bit of tax relief, usually temporary, apportioned for political purposes to groups favored by a reigning political party.

During election times, epistemological confusion – calling a tax credit or temporary suspension of a tax a “tax cut” – is everywhere, because give-backs and tax relief, however temporary, purchase votes, and the party in power is always interested in purchasing votes so that they may retain office and eventually raise the level of taxation to purchase vote and retain political power.

Connecticut’s temporary tax cuts and credits are built on shifting sand.

“The tax cuts,” a Hartford paper noted, “are possible because of a quickly growing state budget surplus and more than $2 billion in federal stimulus funds over 2 years that have helped fund numerous programs across the state.” The state’s budget surplus – i.e., the amount of money the state has overtaxed its citizens – is projected to reach $4 billion. And the federal stimulus funds aggravate inflation and possibly a pending recession. It takes Connecticut about 10 years to recover from a national recession.

It gets worse: The money that will finance more excessive spending is finite, and temporary, but the spending it purchases is mostly permanent and more costly than Connecticut taxpayers can afford in an era of mounting inflation, which reduces the purchasing power of the dollar, and a diminishing population.

The Yankee Institute devoted a carefully researched paper, CT’s Growing Problem: Population Trends in the Constitution State, to Connecticut’s dangerous population issues over the past few decades. The 2020 U.S. Census shows Connecticut as a negative outlier: “In a decade when the nation’s population grew by 7.4 percent, Connecticut’s population grew barely at all – less than 1 percentage point. Only 3 states ranked below Connecticut: West Virginia, Illinois and Mississippi, all of which lost population.”

If the future in Connecticut “ain’t what it used to be,” perhaps true reformers who wish to advance the public good should focus on the palpable effects ruinous policy has on the future. It is at least worth discussing whether state policy makers spend money like drunken sailors because, so long as the state can pass on to future generations the disastrous, but quite predictable consequences of hedonistic spending, politicians now serving in the General Assembly needn’t worry overmuch about their own immediate job prospects.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Don Pesci: Give the Ukrainians back their skies

The Black Madonna of Czestochowa

VERNON, Conn.

Just before the joy of Easter broke upon us, Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow, far from Russian bombardments in Ukraine.

In an interviewed on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” Nehammer said that Putin thinks he is winning the war in Ukraine despite heavy military losses and the fruitless non-stop bombing of Ukrainian cities. Putin certainly has left his mark on Ukrainian cities, and will continue to do so as long as Ukraine’s military cannot close Ukrainian air space to what can only be called urban carpet bombing.

More bombing in Bucha and Mariupol, for instance, can do little more than disturb the rubble of Putin’s carefully chosen targets.

There is not a single military man in Connecticut, from private first class to general, who would not tell you that whoever controls the skies in a war also controls ground offenses, however brave and resolute the resistance.

“We have to confront him [Putin] with that, what we have seen in Ukraine,” said Nehammer.

What the entire world has seen in Ukraine are corpses. According to an Associated Press report, Nehammer “also said he confronted Putin with what he saw during a visit to the Kyiv suburb of Bucha, where more than 350 bodies have been found along with evidence of killings and torture under Russian occupation, and ‘it was not a friendly conversation.’"

A noble Ukrainian resistance to Putin’s terror regime is lost on Putin, who calculates that nobility, honor and patriotism can be sufficiently answered by more frequent remote bombing and deadly trip wire devices placed after strategic withdrawals in refrigerators, the trunks of cars and under corpses his troops have left behind in Bucha and Mariupol.

“In the Kyiv region,” the AP reported, “authorities have reported finding the bodies of more than 900 civilians, most shot dead, since Russian troops retreated two weeks ago.”

President Biden and other Democrats continue to tout the efficacy of sanctions, much appreciated by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. But both presidents know that sanctions are neither offensive nor defensive weapons of a kind Ukraine needs to stop the Russian assault on Mariupol, for weeks Putin’s terrorist playground. Should Mariupo completly fall to Russia, Putin will be able to construct a land bridge from Russia to Crimea, surrendered to Russia during the administration of President Obama and Vice President Biden with hardly a whimper.

Even U.S. Sen. Dick Blumenthal, the Connecticut Democrat, believes that Ukraine may not be able to survive Putin’s latest attentions unless the United States is willing to supply the country with air power that will allow Ukraine to recover its skies from the Russians.

Newly returned from Poland, Blumenthal recently told New Britain Polish-American and Ukrainian American leaders, “If I have one plea to the president of the United States, it is provide more air defense to the people and the brave freedom fighters of Ukraine. The anguish and grief in their eyes is heartbreaking and harrowing. It was one of the most moving moments of my life to talk with them -- we spent the whole day at the border crossing where just hours before the Russians bombed the town just 12 miles away.”

There are many Ukrainian churches in Connecticut. Two weeks before Easter, my wife, Andree, and I visited a Ukrainian church in Hartford and after Mass had a brief talk with a priest who hails from Lviv, a city in western Ukraine that has not yet been entirely leveled by Putin, whom the priest likely regards, somewhat charitably, as the Judas of Christian Orthodoxy.

Diplomacy is fine, but it has not saved a single Ukrainian life, we were given to understand. Ukrainians are hopeful believers in the promises of God.

We spent Easter – Holy Saturday actually – in a church in Vernon my wife sometimes calls “the Polish church.” There the choir seems to call us from Heaven itself, and a representation of Poland's most well-known icon, the Black Madonna of Czestochowa, hangs just to the left of Christ on the cross.

When Mary, here portrayed sorrowfully near the cross, presented Jesus in the temple, she was told that, however joyful the moment, a sword one day would pierce her heart.

Simon clasped Jesus in his arms and, recognizing his divinity, said “Sovereign Lord, as you have promised, you may now dismiss your servant in peace. For my eyes have seen your salvation, which you have prepared in the sight of all nations a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and the glory of your people Israel.”

And then Simon, turning to Mary, said, “This child is destined to cause the falling and rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be spoken against, so that the thoughts of many hearts will be revealed. And a sword will pierce your own soul too.”

There are forebodings of despair everywhere in the testimony of the Apostles and the Fathers of the Christian Church. Over and against them all, my Ukrainian priest reminded us, stands the towering promises of God that we Christians celebrate at Easter.

Christ meets Mary Magdalene at the empty tomb and asks, “Woman, why are you weeping? Whom are you seeking?”

Supposing Him to be the gardener, she pleads, “Sir, if you have carried Him away, tell me where you have laid Him, and I will take Him away.”

Jesus said to her, “Mary!”

She then recognizes Him.

“Rabboni!”

“Do not cling to Me, for I have not yet ascended to My Father; but go to My brethren and say to them, ‘I am ascending to My Father and your Father, and to My God and your God.’ Mary Magdalene came and told the disciples that she had seen the Lord, and that He had spoken these things to her.”

Later, the first word the risen Christ brings to his disciples, cowering as usual in fear, is “Peace be with you.”

But His is not peace “as the world knows peace. These things I have spoken unto you, that in me ye might have peace. In the world ye shall have tribulation. But be of good cheer -- I have overcome the world.”

A sword cleaves my priest’s heart. In Ukraine, the streets flow with blood and tears. My Ukrainians, the priest tells us, forget nothing, remember everything, and live in hope.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Don Pesci: Conn.’s temporary gasoline-tax cut and trying to repeal economic common sense

Major roads of Connecticut

VERNON, Conn.

The default position of Connecticut’s majority Democrats on the matter of getting and spending has not changed within the past three decades: Tax cuts, infrequently imposed, should be temporary and bravely endured, while tax increases, deployed for the most part to satisfy imperious state-employee-union demands, should be permanent.

The recent temporary suspension of Connecticut’s 25-cent-a-gallon excise gasoline tax conforms to the default position of Democrats who have controlled Connecticut’s General Assembly for the last 30 years: The tax is to be suspended – operative word – “temporarily” from April to July 1.

Connecticut Democrats, it should seem obvious, are reading from a national Democratic script.

The increase in the price of gasoline, they say, is due chiefly to the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine and the greedy oil barons.

The debate in the General Assembly on reducing Connecticut’s gasoline tax centered upon whether the reduction should be temporary or permanent.

“Rep. Sean Scanlon, a Guilford Democrat who co-chairs the tax-writing committee,” one newspaper noted, “said many constituents have been hurting from the rising prices at the pump, which was recently an average of $4.32 a gallon.

“Our constituents did not start a war in Ukraine,’' Scanlon argued. “Our constituents did not contribute to the global supply chain. ... This is a great first step that we can make to give them some affordability, some relief. ... At least we’re doing something.”

The newspaper correctly noted, “The tax cuts are possible partly because the state has large budget surpluses in two separate funds due to increased federal stimulus money and capital gains taxes from Wall Street increases, paid largely by millionaires and billionaires in Fairfield County.”

In the state Senate chamber, also dominated by Democrats, Will Haskell, of Westport, rose to the occasion. Haskell argued that the gasoline-tax cut should not be permanent because providing permanent relief would deliver a “debilitating blow’' to the state’s plans to spend millions of dollars to fix roads and bridges. The paper quoted Haskell: “Gas prices are high, but not because of taxes. It’s because of [Russian dictator Vladimir] Putin.”

The federal government – which prints money, borrows money and acquires money through excessive taxation – is flush with funds now being distributed by the Biden administration to various political receptacles, some say for political purposes. In many instances, states are using the funds to offset business slowdowns caused by, some argue, imprudent decisions made by governors and federal officials that have produced a worker shortage. Common sense tells us that if you provide a living salary to workers not to work, they will not work.

High business taxes, an increase in the supply of money flowing from private pockets to the public purse, and labor shortages have produced too few goods, resulting in inflation – too many dollars chasing too few goods.

The high price of goods and services may also be attributed to a continuing effort by progressives in the United States to repeal a central law of a free-market economy, the law of supply and demand, which holds that when demand is a constant and supply is diminished, prices on all goods and services rise. The rise in prices has less to do with the greed of billionaire CEOs than a Darwinian survival-of-the fittest-impulse in over-regulated markets centrally directed by Washington politicians. Large business can survive a large regulator drag on profits. Higher taxes and an increasing regulatory burden swamp smaller businesses and, of course, make it much easier for the larger fish to swallow the minnows.

The empty shelves in Russian stores during the good old days of the Soviet Union were attributed by underpaid “workers of the world” in Russia to central planning. In the so-called “captive nations,” the necklace of states now threatened militarily by Vladimir Putin, workers used to joke among each other, “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.”

The Democratic Party program runs against the grain of good sense. Every worker in the United States knows that personal debt should be discharged by responsible debt holders willing to cut spending and pay down the debt.

Temporary reductions in taxes are insufficient to pay down a debt in Connecticut that has swelled over the years to about $57 billion. And given past performance, no one in the state can be certain that increased taxes will be put to such purposes by an administrative apparatus, growing daily, that had in the past raided various Connecticut lockboxes to pay for current expenses.

The solution to Connecticut’s most pressing economic problems is disarmingly simple: Enrich the state’s creative middle class by cutting taxes and regulations, pay down debt, and work hard to dissolve the entangling alliances between a tax-thirsty government and an even more tax-thirsty conglomeration of various state employee unions.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

The Mystic River Bascule Bridge, built in 1922, carries US 1 over the Mystic River in Connecticut. The famous span connects Groton with the Stonington.

Don Pesci: Self-nominating himself to be Lamont’s Machiavelli?

Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527), Florentine diplomat, writer and political theorist. He’s most famous as author of The Prince, a realist/cynical instruction guide for new princes and royals.

VERNON, Conn.

“If men were angels,” said James Madison, “no government would be necessary.’’

And if governors were angels, no political advisers such as John Droney, former Connecticut Democratic Party chairman and supporter of Gov. Ned Lamont, would be necessary

Droney along with other angels and academics, are now offering their expertise, which is considerable, to Governor Lamont, battered for the last couple of weeks for having been too opaque concerning the wicked Machiavellian way of professional politicians.

Somewhat like former President Trump, Lamont is not a professional politician; he is a millionaire who lives in toney Greenwich, along with other millionaires such as U.S. Sen. Dick Blumenthal. He makes lots of money – Greenwich is a rather high priced burg – but less than his enterprising wife, Annie Lamont.

Droney is caught spilling the political beans in a Hartford Courant piece titled “As Gov. Lamont faces questions on Annie Lamont’s investments and state contracts, critics say more transparency is needed.”

Here is Droney on the indispensability of Droney: “His [Lamont’s] crew is not the most sophisticated political operatives in the world. They didn’t have people who are very familiar with all the black arts of politics who would say, ‘You’ve got to do this, and you’ve got to do that.’ I don’t think that goes on in their minds.”

And: “He doesn’t have [former state Republican chairmen] Tom D’Amore and Dick Foley, and he doesn’t have John Droney. He’s got to get somebody who is really a politician as an informal adviser that says to him, ‘Don’t do this and don’t do that for political reasons’ while he’s running for office again.”

My deceased Italian mother whispered to me in a dream last night, “Sure sounds like Droney is angling for a job as the principal Machiavellian in the Lamont administration.”

I admonished her, “There is some truth in what Droney said though.” She nodded her assent, and my dream moved on.

Millionaire politicians could always make good use of campaign advisers. The services of millionaire Trump advisor Steve Bannon may be available at some point.

The general advice bearing down on Lamont like an onrushing freight train appears to be this: If only Lamont had been wiser in the black arts of politics or, failing that, if he had thought to hire someone such as Droney, intimately familiar with the black arts, he would not now be struggling with angelic academics, journalists and the political opposition. Somehow, such an advisor would have stood Lamont in good stead. He would have been transparent, against the best advice of his and Annie’s accountants -- more like likable Ned than the dastardly, redundantly rich Trump.