Ocean stories

Bathymetry of the ocean floor showing the continental shelves and oceanic plateaus (red), the mid-ocean ridges (yellow-green) and the abyssal plains (blue to purple)

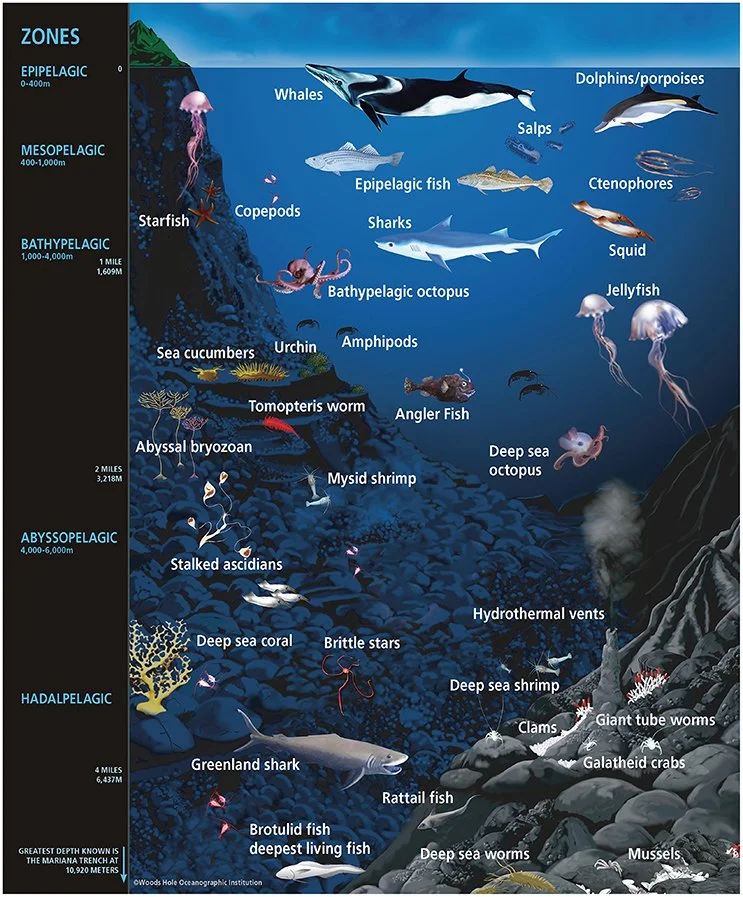

Some ocean life

Text from ecoRI.org

“Surrounded by sounds of calming music and videos of ocean habitats projected onto walls, University of Rhode Island professors and students discussed their experiences with the oceans in an immersive ‘Oceans Tell Stories Through People’ presentation last month at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

“The diverse storytellers shared narratives about their devotion to and reliance upon the sea during their Micronesian upbringing, as a Narragansett tribal elder living near Charlestown Beach, while researching marine ecology in the Bahamas, and in their work in the muddy Ecuadorian mangroves.

“Juxtaposed against the tranquility of the presentation, however, the distressingly common undercurrents of racism, colonialism, and exclusion from our oceans conflated their stories.”

To read the full article, please hit this link.

John O. Harney: N.E.’s changing ethnic demographics; shrinking police forces; honorary degrees and culture wars

1. Northwest Vermont 2. Northeast Kingdom 3. Central Vermont 4. Southern Vermont 5. Great North Woods Region 6. White Mountains 7. Lakes Region 8. Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region 9. Seacoast Region 10. Merrimack River Valley 11. Monadnock Region 12. North Woods 13. Maine Highlands 14. Acadia/Down East 15. Mid-Coast/Penobscot Bay 16. South Coast 17. Mountain and Lakes Region 18. Kennebec Valley 19. North Shore 20. Metro Boston 21. South Shore 22. Cape Cod and Islands 23. South Coast 24. Southeastern Massachusetts 25. Blackstone River Valley 26. Metrowest/Greater Boston 27. Central Massachusetts 28. Pioneer Valley 29. The Berkshires 30. South Country 31. East Bay and Newport 32. Quiet Corner 33. Greater Hartford 34. Central Naugatuck Valley 35. Northwest Hills 36. Southeastern Connecticut/Greater New London 37. Western Connecticut 38. Connecticut Shoreline

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Population studies. The U.S. Census Bureau released new population counts to use in “redistricting” congressional and state legislative districts. Delayed by the pandemic, the counts came close to the legal deadlines for redistricting in some states, raising concerns about whether there would be enough time for public input.

The U.S. population grew 7.4% in 2010-2020, the slowest growth since the 1930s, according to the bureau. The national growth of about 23 million people occurred entirely of people who identified as Hispanic, Asian, Black or more than one race.

The Associated Press reported:

The population under age 18 dropped from 74.2 million in 2010 to 73.1 million in 2020.

The Asian population increased by one-third over the decade, to stand at 24 million, while the Hispanic population grew by almost a quarter, to top 62 million.

White people made up their smallest-ever share of the U.S. population, dropping from 63.7% in 2010 to 57.8% in 2020. The number of non-Hispanic white people dropped to 191 million in 2020.

The number of people identifying as “two or more races” soared from 9 million in 2010 to 33.8 million in 2020, accounting for about 10% of the U.S. population.

A few New England snippets

Maine remains the nation’s oldest and whitest state, even though it saw a 64% increase in the number of Blacks from 2010 to 2020, as well as large increases in the number of Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Connecticut’s population crawled up 0.9% over the decade from 2010 to 2020 to 3,605,944 residents. The number of residents who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) increased from 29% of the population in 2010 to 37% in 2020. Connecticut’s number of congressional seats won’t change, but district borders will.

The total population of the only city on Boston’s South Shore, Quincy, Mass., topped 100,000 (at 101,636), as its Asian population grew to represent nearly 31% of all residents. Further south, the city of Brockton’s population increased by nearly 13% as the white population dropped by 29%, and the Black population increased by 26%.

Amazon jungle. Amazon last week announced it will pay full college tuition for its 750,000 U.S. hourly employees, as well as the cost of earning high school diplomas, GEDs, English as a Second Language (ESL) and other certifications. While collecting praise for its educational goodwill, stories of dire conditions in the e-commerce giant’s workplace also triggered a new California law that would ban all warehouses from imposing penalties for “time off-task” (which reportedly discouraged workers from using the bathroom) and prohibit retaliation against workers who complain.

Police shrink. Police forces in New England have recently felt new recruitment and retention pressures. In August 2021, The Providence Journal ran a piece headlined “Promises made, promises delivered? A look at reforms to New England police departments.” GoLocal reported that month that Providence policing staff levels stood at 403, down from 500 or so in the 1980s under then-Mayor David Cicilline. The number of officers employed by Maine’s city and town police departments and county sheriffs’ offices shrank by nearly 6% between 2015 and 2020, according to the Maine Criminal Justice Academy. Reporter Lia Russell of the Bangor Daily News noted, “It’s also a challenge that police in Maine are far from alone in facing, especially following a year during which police practices across the nation were called into question following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin.” The Burlington, Vt., City Council in August defeated efforts to reverse a steep cut in city police ranks. The police department currently has 75 sworn officers, down from 90 in June 2020. A survey by the police officers’ union found that roughly half of Burlington cops were actively seeking employment elsewhere.

Honor roll. Honorary degrees are becoming something of a frontline in the culture wars. Springfield College alumnus Donald Brown, who recently coauthored a piece for NEJHE, tells of his alma mater revoking the honorary master of physical education degree it had bestowed on U.S. Olympic Committee Chair Avery Brundage in 1940. In 1968, Brundage pressured the U.S. to take action against two Olympic athletes who gave the Black Power salute after finishing first and second in the 200 meters. That event was only the tip of the iceberg. Brundage had a history of anti-semitism, sexism and racism. Springfield President Mary-Beth Cooper met with the trustees and others and decided to take back the honor. Meanwhile, the University of Rhode Island has been tying itself in knots over the honorary degree it bestowed on Michael Flynn in 2014, before he was appointed Trump’s national security adviser and accused of sedition.

Refugees. After the U.S. ended its longest war (so far) in Afghanistan and the capital of Kabul fell, the question arose of where Afghan refugees would resettle. New England cities, including Worcester, Providence and New Haven, are among those that have readied plans to welcome Afghan refugees. In higher education, Goddard College President Dan Hocoy said it was a “no-brainer” to offer to house Afghan refugees at its Plainfield, Vt., campus for at least two months this upcoming fall. Back in 2004, NEJHE (then Connection) featured an interview with Roger Williams University President Roy J. Nirschel, who died in 2018, and his former wife Paula Nirschel on the university’s role in its community as well as their pioneering initiative to educate Afghan women.

Sunshine state. Before Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis took his most recent stand against fighting COVID, he displayed a narrow-mindedness that seems to always be in fashion. As Inside Higher Ed reported, after expressing concerns about faculty members “indoctrinating” students, DeSantis signed a law requiring that public institutions survey students, faculty and staff members about their viewpoint diversity and sense of intellectual freedom. The Miami Herald reported that DeSantis and state Sen. Ray Rodrigues, the original bill’s Republican sponsor, suggested that the results could inform budget cuts at some institutions. Faculty members have opposed the bill, which also allows students to record their professors teaching in order to file free speech complaints against them.

New colleges in a time of contraction. The nonprofit Norwalk (Conn.) Conservatory of the Arts announced plans to open a new performing-arts college and welcome its first class in August 2022. It’s unusual news amid the stream of college mergers and closures only widened by the pandemic. Among the challenges, many of the faculty members don’t have master of fine arts degrees that accrediting agencies require and, without accreditation, the college’s students won’t be eligible for federal financial aid or Pell Grants.

The Conservatory says the college will consolidate a traditional four-year undergraduate program into two years of intense training and a two-year graduate program into one year. Meanwhile, up the coast, the (Fall River, Mass.) Herald News reports that Denmark-based Maersk Training and Bristol Community College will work together to turn an old seafood packaging plant in New Bedford, Mass., into a National Offshore Wind Institute training facility to train offshore wind workers, complete with classrooms and a deepwater pool to train and recertify workers. (NEJHE has reported on the need to train talent for the burgeoning industry and the coastal economy’s special role in New England.)

Other higher-ed institutions are shapeshifting. After months of discussions and lawsuits, Northeastern University and Mills College reached agreement to establish Mills College at Northeastern University. Founded in 1852, Mills is renowned for its pre-eminence in women’s leadership, access, equity and social justice. Also, billionaire investor Gerald Chan and his family’s Morningside Foundation gave $175 million to the University of Massachusetts Medical School, which will be renamed the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. That’s the largest-ever gift to the UMass system.

Land deals. I was recently struck by a report titled We Need to Focus on the Damn Land: Land Grant Universities and Indigenous Nations in the Northeast. The report was born of a partnership between Smith College students and the nonprofit Farm to Institution New England (FINE) to look at how land grant universities view their historic relationships with local Indigenous tribes and how food can play a role in repairing those relationships. It grabbed my attention, partly because NEJHE has published some interesting stories about Native Americans and New England higher education. (See Native Tribal Scholars: Building an Academic Community and A Different Path Forward, both by J. Cedric Woods and The Dark Ages of Education and a New Hope, by Donna Loring.) And partly because two NEBHE Faculty Diversity Fellows, professors Tatiana M.F. Cruz of Simmons University and Kamille Gentles-Peart of Roger Williams University, are spearheading a fascinating Reparative Justice initiative. Among other things, Cruz and Gentles-Peart have had the courage to remind us that land grant universities in New England occupy the land of Indigenous communities. The Smith-FINE work offered sensible recommendations: Financially support Native and Indigenous faculty, activists, programs on campuses and beyond; offer free tuition for Native American students; hire Indigenous people, and fund their research.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Grace Kelly: What's meant by the 'blue economy'?

The area within red is Narragansett Bay.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Blue is the new green.

The term “blue economy” has been popping up in headlines and economic outlines with increasing frequency during the past 10 years. But what exactly does blue economy mean? And what does it specifically mean for Rhode Island, the self-proclaimed Ocean State? And, to further complicate matters, what does it mean in a COVID-19 world?

A report released in March by the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography, URI’s Coastal Resources Center, and Rhode Island Sea Grant attempts to answer the first two questions — the coronavirus pandemic hadn’t yet emerged during the report’s research period.

Jennifer McCann, director of coastal programs at the Coastal Resources Center, said that state government asked her team to define Rhode Island’s blue economy.

“So I Googled it, of course, and you get the definition from the U.N. and from other big, global programs and from different countries, and then you look at the definitions from different states like California and Michigan, and then you can go down further, and even Cape Cod has a definition of the blue economy,” she said. “Then our team looked at what data was out there, and we interviewed more than sixty people to figure out what they thought Rhode Island’s blue economy is, and so now we have a different definition than anyone else.”

Turns out Rhode Island’s blue economy, which the report defines as “the economic sectors with a direct or indirect link to Rhode Island’s coasts and ocean — defense, marine trades, tourism and recreation, fisheries, aquaculture, ports and shipping, and offshore renewable energy” — has a boatload of potential.

According to the 86-page report, 6 percent to 9 percent of Rhode Islanders work within the state’s ocean-based economy, which is valued at more than $5 billion.

Each sector listed in the report’s definition brings its own strengths to the table.

Ocean-based tourism raked in a whopping $703.6 million in 2018.

According to a 2019 study by Bryant University, the shipping industry at the Quonset Business Park generates nearly 7 percent of the state’s gross domestic product.Narra

The defense industry in Rhode Island uses certain areas of Narragansett Bay as testing grounds for new underwater technologies.

“The U.S. Navy owns an underwater tracking range located in Narraganset Bay. It is a testbed for undersea technology prototypes,” Molly Donohue Magee, executive director of the Middletown-based Southeastern New England Defense Industry Alliance, wrote in an email to ecoRI News. “The Naval Undersea Warfare Center has hosted an annual event, Advanced Naval Technology Exercise (ANTX) where companies can demonstrate their technology and prototypes to Navy engineers and the fleet.”

She goes on to note that ocean technology is the next big thing, and it will provide the state with an opportunity to strengthen its blue economy.

“Rhode Island is the hub of undersea technology,” she wrote. “It’s the home of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center, the Department of Defense’s research laboratory for undersea technology. There are many companies in Rhode Island and the region with unique technology related to the undersea environment. The ocean is the next frontier.”

Catherine Puckett is the owner of the Block Island business Oyster Wench, a shellfish and kelp farm operation. (Coastal Resources Center)

Deep blue economy

In addition to the obvious sectors of the blue economy, McCann made sure to note there are parts of it that might not seem so apparent, like advocacy groups such as Save The Bay or state agencies such as the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC).

“[Y]ou can’t forget about the marine-focused advocacy and civic groups,” McCann said. “And then you look at the role our government agencies have been playing whether it be Real Jobs RI working directly with marine trades and defense and building capacity, or CRMC who is designing our coast so we can have a pristine environment as well as a working waterfront.”

A big takeaway from the recent report, as well as from the state’s most-recent long-term economic development plan, which was approved in January, is that there is room for improvement.

During a January Rhode Island Commerce Corporation meeting that discussed the long-term economic development plan, titled Rhode Island Innovates 2.0 and written by Bruce Katz, Gov. Gina Raimondo is quoted as saying, “Basically, his analysis is: ‘Listen, you’ve made a lot of progress the past few years. But still a relatively small portion of our economy is what I would call advanced — high wage, high skill.’”

The governor went on to say that the state needs to do more to advance the education and skill of the average Rhode Islander.

Tide is high

While growing the blue economy was already seen as somewhat of an uphill battle, the coronavirus pandemic has thrown another obstacle in the way.

For instance, as of April 24, Discover Newport, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting the city of Newport and its ocean-centric tourism industry, had laid off 18 of its 22 employees, and expects to see a fall in annual revenue from $3.7 million to a little over a $1 million.

A variety of organizations that fall within the blue economy, such as Rhode Island Marine Trade Association, the Rhode Island Hospitality Association, Polaris MEP, and the Southeastern New England Defense Industry Alliance, have recently banded together to try to revive the economic momentum lost.

For McCann, this collaboration was always essential to a thriving blue economy, even before the virus took its economic and public-health toll.

“We need to work together,” she said. “That’s the way we are going to sustainably grow our state. If we just focus on economics or higher-ed, we’re not efficiently moving forward for sustainable growth in our state.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News reporter.

Dooley a great URI president

The Chester H. Kirk Center for Advanced Technology at the University of Rhode Island main campus, in Kingston

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

David Dooley has been a great president of the University of Rhode Island. He’ll retire in June 2021.

He’s helped bring in the strongest and most diverse student body and faculty the university has ever had, who have done widely recognized research in URI’s nationally, and in some cases internationally, known centers of excellence. He’s overseen construction of functionally superb and architecturally important new buildings while improving the aesthetics of the already bucolic campus. He’s been very adept at raising money to steadily raise the university’s stature.

What makes the achievements of Mr. Dooley, a chemist by training, all the more impressive is that his tenure started in July 2009, a very difficult time because of the Great Recession. He’ll face new and familiar issues as he helps guide the university and his anointed successor through the next year, which is bound to be very difficult one for American academia. The university is lucky that he’ll be in charge as this crisis rolls on

Pearl Macek: N.E. ocean fishermen worry about sector's sustainability

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

PROVIDENCE

Fishermen, scientists and interested citizens gathered in mid-April at Rhode Island College for a panel discussion about whether commercial ocean fishing is, or can be, sustainable.

The panel consisted of six speakers who discussed the current state of fish populations within U.S. waters, climate change and its impact on fish stocks, and the current rules and regulations imposed on commercial fishermen. The discussion was often heated, and it was obvious that the fishermen, both on the panel and in the audience, weren’t happy with current catch quotas and monitoring regulations.

Panelist John Bullard, the Northeast regional administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said commercial fishing is “definitely sustainable.” But fishermen David Goethel and Mark Phillips, also on the panel, believe the more important question to explore is whether fishing communities are sustainable. Both fishermen said catch quotas and the crippling expenses fishermen have to face both to run their boats and pay catch monitors are making fishing as a way of life all but impossible.

“The smell of fish is gone, replaced by burnt coffee,” Phillips said about the traditional fishing docks of New England.

NOAA regulates the fishing industry, and both Phillips and Goethel are involved in a lawsuit against the federal agency regarding the costs incurred by New England fishermen who now have to pay monitors about $700 a day to be on their boats.

Traditionally, the monitoring system was federally funded, but commercial fishermen now have to pay the monitors’ wages, a burden that many fishermen believe will push them toward bankruptcy. The lawsuit was filed last December in federal district court in Concord, N.H.

The audience clapped almost every time Phillips and Goethel spoke about the need for less regulation and more freedom to continue the tradition of small-scale commercial fishing. Phillips bemoaned the fact that U.S. fishermen are only allowed to fish one-third of Georges Bank, one of the most valuable fishing grounds off North America and easily accessible by New England fishermen.

He said fish stocks follow a natural cycle completely independent of fishing, and that every 15 to 20 years a fish population crashes and then rebounds. Phillips also said that when fishermen aren’t allowed to harvest a particular fish stock, the population often times dies off because of disease caused, at least in part, by overpopulation. He claimed there are more fish in the Atlantic Ocean than there were 20 to 30 years ago.

NOAA recently released its annual report to Congress on the status of U.S. fisheries and the numbers are fairly promising: the number of stocks listed as subject to overfishing or overfished remain near an all-time low, with only 9 percent of stocks subject to overfishing and 16 percent of stocks being overfished. Overfishing occurs when more fish are caught then the population can replace; overfished means the current population is 35 percent or below the estimated original population. A fish population can become overfished for reasons outside of fishing, such as disease, natural mortality and changes in environmental conditions.

The topic of climate change also came up frequently in the conversation.

“Climate change is a big problem we have to face,” said Jake Kritzer, director of the Fishery Solutions Center team at the Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group. He noted that a reduction in salinity and nutrients in ocean waters has caused a decrease in the production of plankton.

“Every fishery management plan has to take climate change into consideration,” Bullard said. He also spoke about whole species of fish and marine crustaceans moving further north as New England’s coastal waters get warmer. In recent years, Maine lobstermen have experienced a glut of lobster, which drove prices down to the point that fishermen refused to harvest them until prices increased.

“Fisherman should be advocates,” said Graham Forrester, a professor in the Department of Natural Resources Science at the University of Rhode Island, as he tried to be a unifying voice on a panel that was bitterly divided between fishermen and scientists. “We are struggling in the scientific community to understand these problems.”

At the beginning of the discussion, each member of the audience was given an electronic remote control with which they could answer if they thought fishing was sustainable. At the beginning of the discussion, 69 percent of the audience said yes; by the end of the discussion, that number increased to 78 percent.

In the panelists’ closing remarks Bullard extended a metaphorical olive branch to the fishermen both on the panel and in the audience by saying that regulating the fishing industry needed to be improved, because fishermen have the “hardest job in the world” and “we are making their place of business a hostile environment.”

Pearl Macek is a contributing writer for ecoRI News.