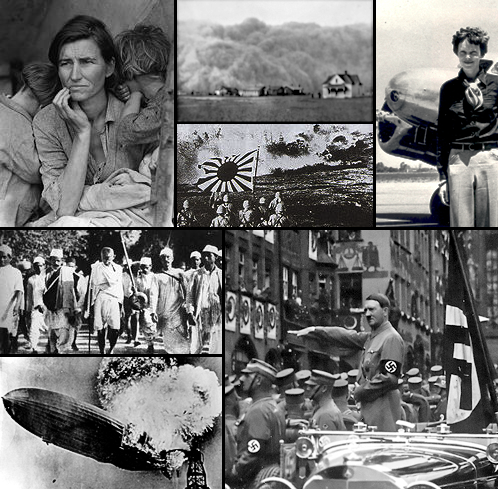

David Ekbladh: Today’s world recalls the ‘30’s more than the Cold War

From Wikipedia: Montage of images from the '30's

MEDFORD, Mass.

The past decade and a half has seen upheaval across the globe. The 2008 financial crisis and its fallout, the COVID-19 pandemic and major regional conflicts in Sudan, the Middle East, Ukraine and elsewhere have left residual uncertainty. Added to this is a tense, growing rivalry between the U.S. and its perceived opponents, particularly China.

In response to these jarring times, commentators have often reached for the easy analogy of the post-1945 era to explain geopolitics. The world is, we are told repeatedly, entering a “new Cold War.”

But as a historian of the U.S.’s place in the world, these references to a conflict that pitted the West in a decades-long ideological battle with the Soviet Union and its allies – and the ripples the Cold War had around the globe – are a flawed lens to view today’s events. To a critical eye, the world looks less like the structured competition of that Cold War and more like the grinding collapse of world order that took place during the 1930s.

The ‘low dishonest decade’

In 1939, the poet W.H. Auden referred to the previous 10 years as the “low dishonest decade” – a time that bred uncertainty and conflict.

From the vantage of almost a century of hindsight, the period from the Wall Street Crash of 1929 to the onset of World War II can be distorted by loaded terms like “isolationism” or “appeasement.” The decade is cast as a morality play about the rise of figures like Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini and simple tales of aggression appeased.

But the era was much more complicated. Powerful forces in the 1930s reshaped economies, societies and political beliefs. Understanding these dynamics can provide clarity for the confounding events of recent years.

Greater and lesser depressions

The Great Depression defined the 1930s across the world. It was not, as it is often remembered, simply the stock market crash of 1929. That was merely an overture to a large-scale unraveling of the world economy that lasted a painfully long time.

Persistent economic problems impacted economies and individuals from Minneapolis to Mumbai, India, and wrought profound cultural, social and, ultimately, political changes. Meanwhile, the length of the Great Depression and its resistance to standard solutions – such as simply letting market forces “purge the rot” of a massive crisis – discredited the laissez faire approach to economics and the liberal capitalist states that supported it.

The “Lesser Depression” that followed the 2008 financial crisis produced something similar – throwing international and domestic economies into chaos, making billions insecure and discrediting a liberal globalization that had ruled since the 1990s.

In both the greater and lesser depressions, people around the world had their lives upended and, finding established ideas, elites and institutions wanting, turned to more radical and extreme voices.

The 1929 stock market crash resulted in a loss of trust for financial institutions. AP Photo

It wasn’t just Wall Street that crashed; for many, the crisis undercut the ideology driving the U.S. and many parts of the world: liberalism. In the 1930s, this skepticism bred questions of whether democracy and capitalism, already beset with contradictions in the form of discrimination, racism and empire, were suited for the demands of the modern world. Over the past decade, we have similarly seen voters turn to authoritarian-leaning populists in countries around the world.

American essayist Edmund Wilson lamented in 1931: “We have lost … not merely our way in the economic labyrinth but our conviction of the value of what we are doing.” Writers in major magazines accounted for “why liberalism is bankrupt.”

Today, figures on the left and right can similarly share in a view articulated by conservative political scientist Patrick Deneen in his book, “Why Liberalism Failed.”

Ill winds

Liberalism – an ideology broadly based on individual freedoms and rule of law as well as a faith in private property and the free market – was touted by its backers as a way to bring democratization and economic prosperity to the world. But recently, liberal “globalization” has hit the skids.

The Great Depression had a similar effect. The optimism of the 1920s – a period some called the “first wave” of democratization – collapsed as countries from Japan to Poland established populist, authoritarian governments.

A Japanese military parade on the second anniversary of the Sino-Japanese conflict in Manchuria. Imagno/Getty Images

The rise today of figures like Hungary’s Victor Orban, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and China’s Xi Jinping remind historians of the continuing appeal of authoritarianism in moments of uncertainty.

Both eras share a growing fragmentation in the world economy in which countries, including the U.S., tried to staunch economic bleeding by raising tariffs to protect domestic industries.

Economic nationalism, although hotly debated and opposed, became a dominant force globally in the 1930s. This is mirrored by recent appeals of protectionist policies in many countries, including the U.S.

A world of grievance

While the Great Depression sparked a “New Deal” in the United States where the government took on new roles in the economy and society, elsewhere people burned by the implosion of a liberal world economy saw the rise of regimes that placed enormous power in the hands of the central government.

The appeal today of China’s model of authoritarian economic growth, and the image of the strongman embodied by Orban, Putin and others – not only in parts of the “Global South” but also in parts of the West – echoes the 1930s.

The Depression intensified a set of what were called “totalitarian” ideologies: fascism in Italy, communism in Russia, militarism in Japan and, above all, Nazism in Germany.

Importantly, it gave these systems a level of legitimacy in the eyes of many around the world, particularly when compared to doddering liberal governments that seemed unable to offer answers to the crises.

Some of these totalitarian regimes had preexisting grievances with the world established after World War I. And, after the failure of a global order based on liberal principles to deliver stability, they set out to reshape it on their own terms.

Observers today may express shock at the return of large-scale war and the challenge it poses to global stability. But it has a distinct parallel to the Depression years.

Early in the 1930s, countries like Japan moved to revise the world system through force – hence the reason such nations were known as “revisionist.” Slicing off pieces of China, specifically Manchuria in 1931, was met — not unlike Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014 — with little more than nonrecognition from the Western democracies.

As the decade progressed, open military aggression spread. China became a bellwether as its anti-imperial war for self-preservation against Japan was haltingly supported by other powers. Ukrainians today might well understand this parallel.

Ethiopia, Spain, Czechoslovakia and eventually Poland became targets for “revisionist” states using military aggression, or the threat of it, to reshape the international order in their own image.

Ironically, by the end of the 1930s, many living through those crisis years saw their own “cold war” against the regimes and methods of states like Nazi Germany. They used those very words to describe the breakdown of normal international affairs into a scrum of constant, sometimes violent, competition. French observers described a period of “no peace, no war” or a “demi guerre.”

Figures at the time understood that it was less an ongoing competition than a crucible for norms and relationships being forged anew. Their words echo in the sentiments of those who see today the forging of a new multipolar world and the rise of regional powers looking to expand their own local influences.

Taking the reins

It is sobering to compare our current moment with one in the past whose terminus was global war.

Historical parallels are never perfect, but they do invite us to reconsider our present. Our future neither has to be a reprise of the “hot war” that concluded the 1930s, nor the Cold War that followed.

The rising power and capabilities of countries like Brazil, India and other regional powers remind one that historical actors evolve and change. However, acknowledging that our own era, like the 1930s, is a complicated multipolar period, buffeted by serious crises, allows us to see that tectonic forces are again reshaping many basic relationships. Comprehending this offers us a chance to rein in forces that in another time led to catastrophe.

David Ekbladh is a professor of history at Tufts University, in Medford, Mass.

Disclosure statement

David Ekbladh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

‘Getting back my humanity’

Carmichael Hall on the Rez Quad at Tufts

—Photo by Jellymuffin40

Tufts College circa 1854, on Walnut Hill, soon after its founding, in 1852.

Edited from a report by the New England Council, based on a Boston Globe story

“An initiative by Tufts University, has achieved remarkable success in recent years by allowing inmates to pursue and complete a college education. The Tufts University Prison Initiative at the Tisch College (TUPIT), at Tufts’s main campus, in Medford, Mass., established in 2016, fosters collaboration between Tufts faculty, students, and both incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. This partnership aims to address challenges related to mass incarceration and racial justice. TUPIT also provides a unique opportunity for students who begin their studies while incarcerated to continue and complete their education on the Tufts campus after their release.

“TUPIT was created by Hilary Binda, a senior lecturer at Tufts, and now the program’s executive director. TUPIT also includes the Tufts Educational Reentry Network, MyTERN, an accredited one-year college and reentry program for people post-incarceration.

“One of the program’s graduates, 33-year-old Juan Pagan, said in his graduation speech, ‘Professors affirming that I am worthy and have something positive to offer society is the greatest gift I have ever received. I now know that I can be an asset to my family and community because [the program] helped me gain back that ineffable part of me that prison repressed — my humanity.’’

John O. Harney: Some big changes at the top

The (Brutalist) Federal Reserve Bank of Boston tower, at the edge of the Boston financial district.

— Photo by Fox-orian

(New England Diary is catching up with this report, first published Feb. 15.)

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston named University of Michigan Provost Susan M. Collins to be the bank’s next president and CEO. An international macroeconomist, Collins will be the first Black woman to lead a regional bank in the 108-year history of the Fed system. In addition to being the University of Michigan’s provost and executive vice president for academic affairs, Collins is the Edward M. Gramlich Collegiate Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics. She holds an undergraduate degree from Harvard University and a doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She will succeed Eric Rosengren, who retired in September after 14 years leading the Boston Fed.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology President L. Rafael Reif announced he will leave the post he has held for the past decade at the end of 2022. A native of Venezuela, Reif began working at MIT as an electrical engineering professor in 1980, then served seven years as provost before being named president in 2012. Among other things, he presided over a $1 billion commitment to a new College of Computing to address the global opportunities and challenges presented by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and oversaw the revitalization of MIT’s physical campus and the neighboring Kendall Square in Cambridge, Mass. Reif said he will take a sabbatical, then return to MIT’s faculty in its Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

Tufts University President Anthony Monaco told the campus that he will step down in the summer of 2023 after 12 years leading the university. A geneticist by training, Monaco ran a center for human genetics at Oxford University in the U.K. and, at Tufts, worked with the Broad Institute on COVID-19 testing programs that helped universities return to in-person learning. Among his accomplishments, Monaco oversaw the university’s 2016 acquisition of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston as well as the removal of the “Sackler” name from its medical school after the Sackler family and its company, Purdue Pharma, were found to be key players in the opioid crisis.

The Biden administration tapped David Cash, dean of the John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at UMass Boston and former commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, to be the regional administrator for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in New England.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The England Journal of Higher Education.

John O. Harney: Update on college news in New England

At Wheaton College, which has done very well in facing COVID-19. Left to right: Emerson Hall, Larcom Hall, Park Hall, Mary Lyon Hall, Knapton Hall and Cole Chapel.

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Faculty diversity. In the early 1990s, NEBHE, the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) and the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) collaborated to develop the first Compact for Faculty Diversity. Formally launched in 1994, with support from the Ford Foundation and Pew Charitable Trust, the compact focused on five key strategies: motivating states and universities to increase financial support for minorities in doctoral programs; increasing institutional support packages to include multiyear fellowships, along with research and teaching assistantships to promote integration into academic departments and doctoral completion; incentivizing academic departments to create supportive environments for minority students through mentorship; sponsoring an annual institute to build support networks and promote teaching ability; and building collaborations for student recruitment to graduate study. With reduced foundation support, collaboration among the three participating regional education compacts declined, but some core compact activities continued through SREB.

Now, NEBHE and its sister regional compacts are launching a collaborative, nine-month planning process to reinvigorate and expand a national Compact for Faculty Diversity. Under the proposed new compact, NEBHE, the Midwestern Higher Education Compact (MHEC), SREB and WICHE would collaborate to invest in the achievement of diversity, equity and inclusion in faculty and staff at postsecondary institutions in all 50 states. Ansley Abraham, the founding director of the SREB State Doctoral Scholars Program at the SREB, has been instrumental in the design and execution of that initiative. He recently published this short piece in Inside Higher Ed.

Fighting COVID. As the head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned of the roughest winter in U.S. public-health history, Wheaton College has stood out. Our Wheaton, in Norton, Mass. (not to be confused with the Wheaton College in Illinois) developed a plan based on science that has kept positive cases low on campus and allowed in-person classes during the fall semester. Wheaton was able to limit the college’s overall fall semester case count to 23 (a .06 positivity rate among 35,000 tests) due to strong protocols, rigorous testing through the Cambridge, Mass.-based Broad Institute and a shared commitment from the community, especially students. In early November, as cases were spiking across the U.S., the private liberal arts college had its own spike of 13 positive cases in one day. But thanks to immediate contact tracing in partnership with the Massachusetts Community Tracing Collaborative, only one positive case resulted after that day, notes President Dennis Hanno. Part of Wheaton’s success owes to its twice-a-week testing throughout the semester. The college also credits its work with the for-profit In-House Physicians to complement internal staff in managing on-campus testing and quarantine/isolation housing.

New England in D.C. The COVID-19 crisis should make national health positions crucial. Earlier this week, President-elect Joe Biden tapped Dr. Rochelle Walensky, an infectious disease physician at Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, to lead the CDC and Dr. Vivek Murthy, who attended Harvard and Yale and did his residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, to be surgeon general. They’ll work with Dr. Anthony Fauci, the chief medical advisor and College of the Holy Cross graduate who has served six presidents.

Last month, as Biden’s transition team began drawing on the nation’s colleges and universities to prepare to take the reins of government, we flashed back to a 2009 NEJHE piece when Barack Obama was stocking his first administration. “As they form their White House brain trusts, new presidents tend to mine two places for talent: their home states and New England—especially New England’s universities, and especially Harvard,” we noted at the time. Most recently, two New England Congresswomen have scored big promotions on Capitol Hill. Rosa DeLauro (D.-Conn.) became Appropriations chair and Katherine Clark (D.-Mass.) was elected assistant speaker of the House. Richard Neal (D.-Mass.) was already chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee.

Indebted. U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass.), long a champion of canceling student debt, called on Biden to take executive action to cancel student loan debt. “All on his own, President-elect Biden will have the ability to administratively cancel billions of dollars in student loan debt using the authority that Congress has already given to the secretary of education,” she told a Senate Banking Committee hearing. “This is the single most effective economic stimulus that is available through executive action.” About 43 million Americans have a combined total of $1.5 trillion in federal student loan debt. Such debt has been shown to discourage big purchases, growth of new businesses and rates of home ownership among other life milestones. Warren has outlined a plan in which Biden can cancel up to $50,000 in federal student loan debt for borrowers.

Jobless recovery? Everyone knew the public health crisis would be accompanied by an economic crisis. This week, Moody’s Investors Service projected that the 2021 outlook for the U.S. higher-education sector remains negative, as the coronavirus pandemic continues to threaten enrollment and revenue streams. The sector’s operating revenue will decline by 5 percent to 10 percent over the next year, Moody’s projected. The pace of economic recovery remains uncertain, and some universities have issued or refinanced debt to bolster liquidity. (As this biting piece notes, “Just as decreased state funding has caused students to go into debt to cover tuition and fees, universities have taken on debt to keep their doors open.”)

The name of the game for many higher education institutions (HEIs) is coronavirus relief money from the federal government. NEBHE has written letters to Congress calling for increased relief based on the many New England students and families struggling with reduced incomes or job loss and the costs associated with resuming classes that were significantly higher than anticipated. These costs have been growing based on regular virus testing, contact tracing, health monitoring, quarantining, building reconfigurations, expanded health services, intensified cleaning and the ongoing transition to virtual learning. Citing data from the National Student Clearinghouse, NEBHE estimated that New England’s institutions in all sectors lost tuition and fee revenue of $413 million. And that’s counting only revenue from tuition and fees. Most institutions also face additional budget shortfalls due to lost auxiliary revenues (namely, from room and board) and the high costs of compliance with new health regulations and the administration of COVID-19 tests to students, faculty and staff. (When the relief money is spent and by whom is important too. Tom Brady’s sports performance company snagged a Paycheck Protection Program loan of $960,855 in April.) Anna Brown, an economist at Emsi, told our friends at the Boston Business Journal that higher-ed staffers working in dorms, maintenance roles, housing and food services have been hit hard, and faculty will not be far behind

Admissions blast from the past. I’ve overheard too many conversations lately with reference to “testing” and wondered if the subject was COVID testing or interminable academic exams. Given admissions tests being de-emphasized by colleges, we were reminded me of a 10-year-old piece by Tufts University officials on how novel admissions questions would move applicants to flaunt their creativity. The authors told of how “Admissions officers use Kaleidoscope, as well as the other traditional elements of the application, to rate each applicant on one or more of four scales: wise thinking, analytical thinking, practical thinking and creative thinking.” Could be their moment?

Anti-wokism. The U.S. Department of Education held “What is to be Done? Confronting a Culture of Censorship on Campus” on Dec. 8 (presumably not deliberately on the anniversary of John Lennon’s assassination). The hook was to unveil the department’s “Free Speech Hotline” to take complaints of campus violations. The event organizers contended that “Due to strong demand, the event capacity has been increased!” The department’s Assistant Secretary for Postsecondary Education Robert King began noting that we’ll hear from “victims of cancel culture’s pernicious compact” where generally “administrators cave to the mob and punish the culprit.” He noted, “Coming just behind this are Communist-style re-education camps” and assured the audience that the department has launched several investigations into these kinds of offenses like those that land awkwardly in my inbox from Campus Reform. Universities are no place for “wokism,” one speaker warned, adding that calls for diversity and tolerance actually aim to squelch unpopular opinions.

Welcome dreamers. Last week, a federal judge ordered the Trump administration to restore the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program to how it was before the administration announced plans to end it in September 2017. DACA provides protection against deportation and work authorization to certain undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children. DACA participants include many current and former college students. NEBHE issued a statement in support of DACA in September 2017 and has advocated for the initiative’s support.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.