Chris Powell: Wretched excess in the deep; Ellsberg’s lesson

— Photo by Jjm596

MANCHESTER, Conn.

As they descended toward their target 2½ miles under the North Atlantic, the five people aboard in the OceanGate Expeditions submersible vessel Titan were, at least superficially, aware of the risks they were taking for a close look at the wreck of RMS Titanic. They apparently had been compelled to provide a waiver of the company's liability, a waiver that repeatedly noted that the journey could be fatal.

But no one had been killed yet on such expeditions, and the five could consider themselves heroic explorers.

Since the wreck of the Titanic already had been discovered and extensively photographed, there was no necessity for the trip. To the vessel's pilot, the CEO of OceanGate Expeditions, it was a way of making a lot of money -- $250,000 per passenger. For his passengers the trip was more than a bit of arrogance and wretched excess.

Because the vessel imploded at great depth, there is little chance that its occupants suffered or even knew they were being killed. As many in the submarine service and industry in Connecticut know, death by implosion in the deep is instantaneous, a matter of milliseconds, too fast for the human brain to perceive.

In exchange for this mercy there will be no bodies to recover.

Many prayers sought the rescue of the occupants of the Titan, and their loss has been felt throughout the world. Instead of the granting of those prayers, the world has gotten two valuable reminders: first, of the limits imposed on mankind by the natural world, and second, of the incredibly precious smallness of the environment in which humans can survive. Despite many science-fiction movies to the contrary, the environmentalists are right in one respect: There is no Planet B.

While the ocean bottom holds many secrets, as the infinity of the universe does, mankind hardly needs to learn them as much as how to get along with itself and improve life where it can be lived: on the surface of the planet. Lives can be expended far better than in pursuit of another look at a shipwreck, and while the deep will always have to be challenged now and then, the poet George Gordon Byron (1788-1824) saw long ago that it would remain master.

Roll on, thou deep and dark blue Ocean -- roll!

Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain.

Man marks the earth with ruin. His control

Stops with the shore. Upon the watery plain

The wrecks are all thy deed, nor doth remain

A shadow of man's ravage, save his own,

When, for a moment, like a drop of rain,

He sinks into thy depths with bubbling groan,

Without a grave, unknelled, uncoffined, and unknown.

xxx

How should the country remember Daniel Ellsberg, who died the other week?

As national security adviser in 1971, Henry Kissinger called him “the most dangerous man in America” for copying classified documents about the Vietnam war -- the Pentagon Papers -- and distributing them to news organizations.

Ellsberg was charged with espionage. But the Pentagon Papers revealed nothing of battlefield use to the enemy. Instead they showed that the administrations of Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon had been lying to the country about the war. Ellsberg was dangerous only to dishonest and criminal government officials.

Ellsberg might have been convicted except for the crimes the Nixon administration committed in pursuit of him, illegally wiretapping him and burglarizing his psychiatrist's office. So the charges against him were dismissed.

The Ellsberg affair may have been understood best by Nixon aide H.R. Haldeman, a criminal himself. He was taped telling Nixon: "To the ordinary guy, all this is gobbledygook. But out of the gobbledygook comes a very clear thing. .... You can't trust the government. You can't believe what they say. And you can't rely on their judgment. The implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because it shows that people do things the president wants to do even though it's wrong, and the president can be wrong."

Has anything changed in 50 years?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics and other topics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Phyllis Bennis: A tale of two tragedies at sea

Via OtherWords.org

Recent weeks saw two terrible tragedies at sea.

In one, five explorers died when the Titan submersible imploded in the North Atlantic. In the other, over 600 refugees — most of them women and children — drowned in the Mediterranean when their fishing trawler sank.

Both voyages ended in a heartbreaking loss of life. But there were vast differences between the two tragedies in media attention and government response, highlighting just how unequal our world has become.

On board the Titan were two billionaires and one of their sons, along with a CEO and research director of companies tied to undersea adventure tourism. They were headed for the wreckage of the Titanic, which sank 111 years ago.

When the Titan lost contact with its mother ship less than two hours after descent began, calls for assistance immediately went out. Help came quickly from the U.S. and Canadian coast guards and navies, along with support from France and offers from other countries.

Sonar-equipped planes, undersea diving equipment, trained divers, and search ships of every variety steamed to the area. Meanwhile, breathless coverage of the tragedy stayed on the front pages around the world as TV news counted down the hours of oxygen left in the small craft.

The rescue cost is unknown, but initial estimates are around $100 million — a cost that will be footed by taxpayers.

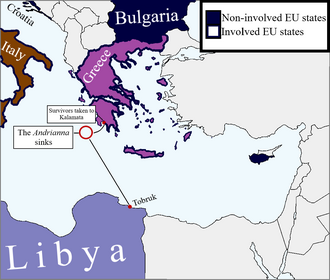

Compare this to the story of the Andriana, which sank off the coast of Greece just two days after the Titan went down. The Andriana was thought to be carrying over 700 people, of whom just 104 survived. No women or children were among the survivors.

The limited news coverage of the Andriana included nothing like the up-close-and-personal human stories of the lives and dreams of the five men aboard the Titan. Except for a few, we don’t even know their names.

They were desperate migrants, many of them refugees, from countries wracked by war, poverty, climate disasters and human-rights violations — including Afghanistan, Syria, Palestine, Pakistan and Egypt. They were sailing from Libya in a decrepit fishing boat, hoping to make it to Europe alive.

The Greek coast guard quickly realized that the ship was in trouble, but didn’t try to rescue the desperate passengers on the deck. Greek authorities made assertions — vehemently disputed by ship captains nearby, migrant advocates, and the passengers themselves — that the ship had turned down offers of assistance.

The ship had been in distress almost two days before it sank, but help didn’t come until it was too late. How many might have been rescued with one-tenth the resources that were rushed to save the very, very people on the Titan?

Europe’s racist approach to migration starts and ends with preventing African, Asian and Arab migrants from entering European territory. But it’s not just a European problem.

Indeed, the continent’s policies on migrants bear a tragic — indeed criminal — similarity to our own in the United States. As thousands of desperate refugees and migrants have died crossing the Mediterranean, thousands more from Central America, the Caribbean, and beyond have died trying to cross the desert along the U.S.-Mexico border.

How many might have been saved if immigration policy were grounded in keeping migrants safe, rather than keeping them out?

The rescue effort mounted for those lost on the Titan shows what’s possible when those in danger are treated like they matter. U.S. officials should work just as hard to rescue poor and endangered migrants as they do the billionaires — their lives matter just as much.

Phyllis Bennis directs the New Internationalism Project at the Institute for Policy Studies.

#Titan

#Andrina

#migrants