James L. Fitzsimmons: Of hurricanes and Huracan

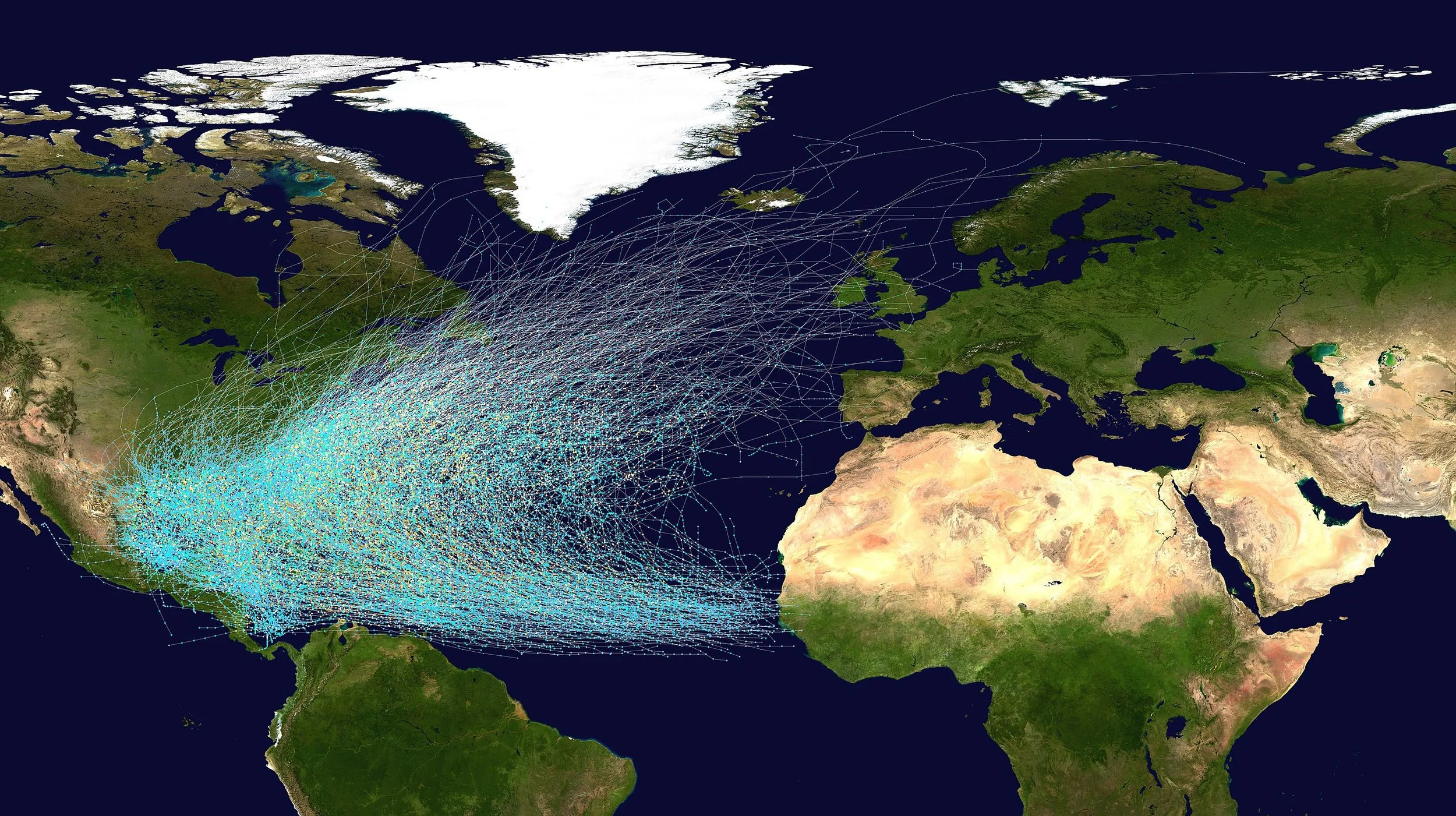

Tracks of North Atlantic tropical cyclones 1851-2019

MIDDLEBURY, Vt.

The ancient Maya believed that everything in the universe, from the natural world to everyday experiences, was part of a single, powerful spiritual force. They were not polytheists who worshipped distinct gods but pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations of that force.

Some of the best evidence for this comes from the behavior of two of the most powerful beings of the Maya world: The first is a creator god whose name is still spoken by millions of people every fall – Huracán, or “Hurricane.” The second is a god of lightning, K'awiil, from the early first millennium C.E.

As a scholar of the Indigenous religions of the Americas, I recognize that these beings, though separated by over 1,000 years, are related and can teach us something about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán, the ‘Heart of Sky’

Huracán was once a god of the K’iche’, one of the Maya peoples who today live in the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one of the main characters of the Popol Vuh, a religious text from the 16th century. His name probably originated in the Caribbean, where other cultures used it to describe the destructive power of storms.

The K’iche’ associated Huracán, which means “one leg” in the K’iche’ language, with weather. He was also their primary god of creation and was responsible for all life on earth, including humans.

Because of this, he was sometimes known as U K'ux K'aj, or “Heart of Sky.” In the K'iche’ language, k'ux was not only the heart but also the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Yet, Huracán was not perfect. He made mistakes and occasionally destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who damaged humans so they would not be his equal. In one such episode, he is believed to have clouded their vision, thus preventing them from being able to see the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was one being who existed as three distinct persons: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied different types of lightning, ranging from enormous bolts to small or sudden flashes of light.

Despite the fact that he was a god of lightning, there were no strict boundaries between his powers and the powers of other gods. Any of them might wield lightning, or create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

Another storm god

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and match their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. One thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was a different version of Huracán called K'awiil. During the first millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras venerated him as a god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

The ancient Maya god K'awiil, left, had an ax or torch in his forehead as well as a snake in place of his right leg. K5164 from the Justin Kerr Maya archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C., CC BY-SA

Illustrations of K'awiil can be found everywhere on Maya pottery and sculpture. He is almost human in many depictions: He has two arms, two legs and a head. But his forehead is the spark of life – and so it usually has something that produces sparks sticking out of it, such as a flint ax or a flaming torch. And one of his legs does not end in a foot. In its place is a snake with an open mouth, from which another being often emerges.

Indeed, rulers, and even gods, once performed ceremonies to K'awiil in order to try and summon other supernatural beings. As personified lightning, he was believed to create portals to other worlds, through which ancestors and gods might travel.

Representation of power

For the ancient Maya, lightning was raw power. It was basic to all creation and destruction. Because of this, the ancient Maya carved and painted many images of K'awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a kind of energy – as a god with “many faces,” or even as part of a triad similar to Huracán.

He was everywhere in ancient Maya art. But he was also never the focus. As raw power, he was used by others to achieve their ends.

Rain gods, for example, wielded him like an ax, creating sparks in seeds for agriculture. Conjurers summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Rulers even carried scepters fashioned in his image during dances and processions.

Moreover, Maya artists always had K'awiil doing something or being used to make something happen. They believed that power was something you did, not something you had. Like a bolt of lightning, power was always shifting, always in motion.

An interdependent world

Because of this, the ancient Maya thought that reality was not static but ever-changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and time, the forces of nature or the animate and inanimate worlds.

Residents wade through a street flooded by Hurricane Helene, in Batabano, Mayabeque province, Cuba, on Sept. 26, 2024. AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, anything could become anything else – and everything was potentially a living being. Rulers could ritually turn themselves into gods. Sculptures could be hacked to death. Even natural features such as mountains were believed to be alive.

These ideas – common in pantheist societies – persist today in some communities in the Americas.

They were once mainstream, however, and were a part of K'iche’ religion 1,000 years later, in the time of Huracán. One of the lessons of the Popol Vuh, told during the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is not that different things exist. Rather it is that they exist independent from one another. Huracán, in this sense, damaged himself by damaging his creations.

Hurricane season every year should remind us that human beings are not independent from nature but part of it. And like Hurácan, when we damage nature we damage ourselves.

James L. Fitzsimmons is a professor of anthropology at Middlebury College.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Jamie Hartmann-Boyce: Benefits of menthol-flavored e-cigarettes may outweigh the risks

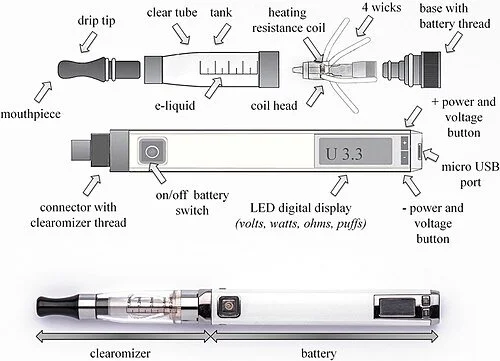

An e-cigarette with transparent clearomizer and changeable dual-coil head. This model allows for a wide range of settings.

On June 21, 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the marketing of the first electronic cigarette products in flavors other than tobacco in the U.S. Of the four new authorized products, two are sealed, prefilled pods with menthol-flavored nicotine liquid that can be used in certain types of e-cigarettes. The other two are disposable nicotine e-cigarettes – meaning once the prefilled menthol liquid is used, the device cannot be used again.

The Conversation asked Jamie Hartmann-Boyce, a health-policy expert who specializes in tobacco control and e-cigarette products, to explain the pros and cons of the FDA’s authorization and what it could mean for vulnerable populations.

AMHERST, MASS.

E-cigarettes, also known as vapes, are hand-held, battery-operated devices that heat a liquid to form a vapor that can be inhaled. This vapor can be manufactured to include flavors. Unlike traditional cigarettes, e-cigarettes do not contain tobacco leaf. E-cigarettes can – but don’t always – contain nicotine.

Until June 21, the only nicotine e-cigarettes authorized for sale in the U.S. were tobacco-flavored. Some organizations, including some tobacco industry advocates, described this as a “de facto flavor ban.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines menthol as a chemical compound found naturally in peppermint and other similar plants.

This is the first time the FDA has authorized marketing of an e-cigarette flavor other than tobacco. “Tobacco flavor” describes a range of flavors that are designed to taste similar to traditional cigarettes.

What are the potential harms, such as risks to kids?

Tobacco companies have historically added menthol to traditional cigarettes to make them seem less harsh and more appealing. Tobacco companies have aggressively marketed menthol cigarettes to Black people. In 2022, the FDA proposed a ban on menthol cigarettes based on their appeal, including to youth, and the potential of such a ban to improve health and prevent deaths. But the proposal has stalled.

Research shows that nontobacco, e-liquid flavors are more appealing than tobacco flavors, including to young people. The FDA has previously denied applications for menthol e-cigarettes, stating that the applications “did not present sufficient scientific evidence to show that the potential benefit to adult smokers outweighs the risks of youth initiation and use.”

How are e-cigarettes regulated in the U.S.?

In the U.S, e-cigarettes with nicotine fall under the authority of the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products. For their products to be legally marketed and sold in the U.S., e-cigarette manufacturers must apply for marketing authorization from the FDA.

The FDA evaluates these applications based on the scientific evidence provided by the manufacturers. To be approved, the applications must demonstrate that permitting marketing of the products would be appropriate for protection of public health.

This means the FDA needs to weigh whether the potential benefits of the product – in other words, its ability to help adults quit smoking – outweigh its risks, including its appeal to youth. Though not risk-free, e-cigarettes are considered much less harmful than smoking. This means that adults who switch from smoking to vaping may benefit from improvements in their health.

The FDA’s authorization of menthol-flavored e-cigarettes underscores the growing body of evidence that vaping can reduce the harms of traditional smoking. But many experts are concerned that the new products will entice more young people and nonsmokers to begin vaping and smoking.

Weren’t flavored vapes already available in the U.S.?

Even though only tobacco e-liquids were authorized for sale before this new announcement, many Americans report using flavored e-liquids, with sweet, fruit and mint and menthol flavors being the most popular. This is in part because many vaping products available in the U.S. haven’t been authorized for marketing or sale. These are referred to as illicit products. In addition, some of the products currently available are still being reviewed by the FDA.

Many of the harms the public associates with vaping – such as the serious vaping-related lung injuries that were widely reported in 2019 and 2020 – have been linked to illicit products and the harmful chemicals some contain, which are not present in FDA-authorized products. Earlier in June, the Justice Department and FDA announced a federal multi-agency taskforce to curb distribution and sale of illegal e-cigarettes. Meanwhile, the U.S. is awash in sleek, colorful and highly potent vapes manufactured in China.

What are the potential health effects?

The best available research doesn’t show any clear differences between menthol and tobacco flavored e-liquid in terms of direct health risks to users.

As mentioned above, research suggests that nontobacco e-liquid flavors are more appealing than tobacco-flavored ones, at least in some groups. This might mean an increase in the risk of nonsmoking youth taking up vaping. But it might also encourage people who smoke to switch to vaping, which can pose fewer risks than smoking. Quitting smoking can also improve the health of other people, by reducing secondhand smoke exposure.

Smoking kills half of its regular users and is the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S. and worldwide. So alternatives that increase chances of successfully quitting smoking can bring substantial health benefits.

To grant authorization for the four new approved products, the FDA had to review an extensive amount of documents and research showing that the benefits of the new products outweighed their risks.

Jamie Hartmann-Boyce is an assistant professor of health promotion and policy at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

She receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and Cancer Research UK, on topics related to tobacco control. She sits on Health Canada's Scientific Advisory Board on Vaping Products and consults for the Truth Initiative.

Adrienne Mayor: Wild animals know how to self-medicate

New Englanders should know that local plants were long used by the region’s Native Americans as medicines before the European colonists arrived. Above, a willow tree, whose bark contains salicylic acid, the active metabolite of aspirin, and used for millennia to relieve pain and reduce fever. Below, many Native American tribes used the leaves of sassafras as medicine to to treat wounds, acne, urinary disorders and high fevers.

.

When a wild orangutan in Sumatra recently suffered a facial wound, apparently after fighting with another male, he did something that caught the attention of the scientists observing him.

The animal chewed the leaves of a liana vine – a plant not normally eaten by apes. Over several days, the orangutan carefully applied the juice to its wound, then covered it with a paste of chewed-up liana. The wound healed with only a faint scar. The tropical plant he selected has antibacterial and antioxidant properties and is known to alleviate pain, fever, bleeding and inflammation.

The striking story was picked up by media worldwide. In interviews and in their research paper, the scientists stated that this is “the first systematically documented case of active wound treatment by a wild animal” with a biologically active plant. The discovery will “provide new insights into the origins of human wound care.”

Fibraurea tinctoria leaves and the orangutan chomping on some of the leaves. Laumer et al, Sci Rep 14, 8932 (2024), CC BY

To me, the behavior of the orangutan sounded familiar. As a historian of ancient science who investigates what Greeks and Romans knew about plants and animals, I was reminded of similar cases reported by Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, Aelian and other naturalists from antiquity. A remarkable body of accounts from ancient to medieval times describes self-medication by many different animals. The animals used plants to treat illness, repel parasites, neutralize poisons and heal wounds.

The term zoopharmacognosy – “animal medicine knowledge” – was invented in 1987. But as the Roman natural historian Pliny pointed out 2,000 years ago, many animals have made medical discoveries useful for humans. Indeed, a large number of medicinal plants used in modern drugs were first discovered by Indigenous peoples and past cultures who observed animals employing plants and emulated them.

What you can learn by watching animals

Some of the earliest written examples of animal self-medication appear in Aristotle’s “History of Animals” from the fourth century BCE, such as the well-known habit of dogs to eat grass when ill, probably for purging and deworming.

Aristotle also noted that after hibernation, bears seek wild garlic as their first food. It is rich in vitamin C, iron and magnesium, healthful nutrients after a long winter’s nap. The Latin name reflects this folk belief: Allium ursinum translates to “bear lily,” and the common name in many other languages refers to bears.

As a hunter lands several arrows in his quarry, a wounded doe nibbles some growing dittany. British Library, Harley MS 4751 (Harley Bestiary), folio 14v, CC BY

Pliny explained how the use of dittany, also known as wild oregano, to treat arrow wounds arose from watching wounded stags grazing on the herb. Aristotle and Dioscorides credited wild goats with the discovery. Vergil, Cicero, Plutarch, Solinus, Celsus and Galen claimed that dittany has the ability to expel an arrowhead and close the wound. Among dittany’s many known phytochemical properties are antiseptic, anti-inflammatory and coagulating effects.

According to Pliny, deer also knew an antidote for toxic plants: wild artichokes. The leaves relieve nausea and stomach cramps and protect the liver. To cure themselves of spider bites, Pliny wrote, deer ate crabs washed up on the beach, and sick goats did the same. Notably, crab shells contain chitosan, which boosts the immune system.

When elephants accidentally swallowed chameleons hidden on green foliage, they ate olive leaves, a natural antibiotic to combat salmonella harbored by lizards. Pliny said ravens eat chameleons, but then ingest bay leaves to counter the lizards’ toxicity. Antibacterial bay leaves relieve diarrhea and gastrointestinal distress. Pliny noted that blackbirds, partridges, jays and pigeons also eat bay leaves for digestive problems.

A weasel wears a belt of rue as it attacks a basilisk in an illustration from a 1600s bestiary. Wenceslaus Hollar/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Weasels were said to roll in the evergreen plant rue to counter wounds and snakebites. Fresh rue is toxic. Its medical value is unclear, but the dried plant is included in many traditional folk medicines. Swallows collect another toxic plant, celandine, to make a poultice for their chicks’ eyes. Snakes emerging from hibernation rub their eyes on fennel. Fennel bulbs contain compounds that promote tissue repair and immunity.

According to the naturalist Aelian, who lived in the third century BCE, the Egyptians traced much of their medical knowledge to the wisdom of animals. Aelian described elephants treating spear wounds with olive flowers and oil. He also mentioned storks, partridges and turtledoves crushing oregano leaves and applying the paste to wounds.

The study of animals’ remedies continued in the Middle Ages. An example from the 12th-century English compendium of animal lore, the Aberdeen Bestiary, tells of bears coating sores with mullein. Folk medicine prescribes this flowering plant to soothe pain and heal burns and wounds, thanks to its anti-inflammatory chemicals.

Ibn al-Durayhim’s 14th-century manuscript “The Usefulness of Animals” reported that swallows healed nestlings’ eyes with turmeric, another anti-inflammatory. He also noted that wild goats chew and apply sphagnum moss to wounds, just as the Sumatran orangutan did with liana. Sphagnum moss dressings neutralize bacteria and combat infection.

Nature’s pharmacopoeia

Of course, these premodern observations were folk knowledge, not formal science. But the stories reveal long-term observation and imitation of diverse animal species self-doctoring with bioactive plants. Just as traditional Indigenous ethnobotany is leading to lifesaving drugs today, scientific testing of the ancient and medieval claims could lead to discoveries of new therapeutic plants.

Animal self-medication has become a rapidly growing scientific discipline. Observers report observations of animals, from birds and rats to porcupines and chimpanzees, deliberately employing an impressive repertoire of medicinal substances. One surprising observation is that finches and sparrows collect cigarette butts. The nicotine kills mites in bird nests. Some veterinarians even allow ailing dogs, horses and other domestic animals to choose their own prescriptions by sniffing various botanical compounds.

Mysteries remain. No one knows how animals sense which plants cure sickness, heal wounds, repel parasites or otherwise promote health. Are they intentionally responding to particular health crises? And how is their knowledge transmitted? What we do know is that we humans have been learning healing secrets by watching animals self-medicate for millennia.

Adrienne Mayor is a research scholar in Classics and History and Philosophy of Science at Stanford University

Adrienne Mayor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

What causes earthquakes in the Northeast?

An 18th-Century woodcut taken from a religious tract showing the effects of the Cape Ann Earthquake, on Nov. 18, 1755, whose magnitude is believed to have been at 6.0-6.3 on the Richter scale.

It’s rare to feel earthquakes in the U.S. Northeast, so the magnitude 4.8 earthquake in New Jersey that shook buildings in New York City and was felt from Maryland to Boston on April 5, 2024, drew a lot of questions. It was one of the strongest earthquakes on record in New Jersey, though there were few reports of damage. A smaller, magnitude 3.8 earthquake and several other smaller aftershocks rattled the region a few hours later. We asked geoscientist Gary Solar to explain what causes earthquakes in this region.

There are many ancient faults in that part of New Jersey that extend through Philadelphia and along the Appalachians, and the other direction, past New York City and into western New England.

These are fractures where gravity can cause the rock on either side to slip, causing the ground to shake. There is no active tectonic plate motion in the area today, but there was about 250 million to 300 million years ago.

The Ramapo Fault, in green, is a major fault zone in New Jersey. The red dots indicate earthquakes of magnitude 3 or higher, reported by the U.S. Geological Survey and National Earthquake Information Center. Alan Kafka/Wikimedia

The earthquake activity in New Jersey on April 5 is similar to the 3.8 magnitude earthquake that we experienced in 2023 in Buffalo, New York. In both cases, the shaking was from gravitational slip on those ancient structures.

In short, rocks slip a little on steep, preexisting fractures. That’s what happened in New Jersey, assuming there was no man-made trigger.

Magnitude 4.8 is pretty large, especially for the Northeast, but it’s likely to have minor effects compared with the much larger ones that cause major damage and loss of life.

The scale used to measure earthquakes is logarithmic, so each integer is a factor of 10. That means a magnitude 6 earthquake is 10 times larger than a magnitude 5 earthquake. The bigger ones, like the magnitude 7.4 earthquake in Tawian a few days earlier, are associated with active plate margins, where two tectonic plates meet.

The vulnerability of buildings to a magnitude 4.8 earthquake would depend on the construction. The building codes in places like California are very strict because California has a major plate boundary fault system – the San Andreas system. New Jersey does not, and correspondingly, building codes don’t account for large earthquakes as a result.

Earthquakes are actually pretty common in the Northeast, but they’re usually so small that few people feel them. The vast majority are magnitude 2.5 or less.

The rare large ones like this are generally not predictable. However, there will likely not be other large earthquakes of similar size in that area for a long time. Once the slip happens in a region like this, the gravitational problem on that ancient fault is typically solved and the system is more stable.

That isn’t the case for active plate margins, like in Turkey, which has had devastating earthquakes in recent years, or rimming the Pacific Ocean. In those areas, tectonic stresses constantly build up as the plates slowly move, and earthquakes are from a failure to stick.

This article, originally published April 5, 2024, has been updated with several smaller aftershocks felt in the region.

James Morton Turner: Renewable energy still only modest factor in powering green manufacturing boom

From The Conversation

WELLESLEY, Mass.

Panasonic’s new US$4 billion battery factory in De Soto, Kansas, is designed to be a model of sustainability – it’s an all-electric factory with no need for a smokestack. When finished, it will cover the size of 48 football fields, employ 4,000 people and produce enough advanced batteries to supply half a million electric cars per year.

But there’s a catch, and it’s a big one.

While the factory will run on wind and solar power much of the time, renewables supplied only 34% of the local utility Evergy’s electricity in 2023.

In much of the U.S., fossil fuels still play a key role in meeting power demand. In fact, Evergy has asked permission to extend the life of an old coal-fired power plant to meet growing demand, including from the battery factory.

With my students at Wellesley College, I’ve been tracking the boom in investments in clean energy manufacturing and how those projects – including battery, solar panel and wind turbine manufacturing and their supply chains – map onto the nation’s electricity grid.

The Kansas battery plant highlights the challenges ahead as the U.S. scales up production of clean energy technologies and weans itself off fossil fuels. It also illustrates the potential for this industry to accelerate the transition to renewable energy nationwide.

The clean tech manufacturing boom

Let’s start with some good news.

In the battery sector alone, companies have announced plans to build 44 major factories with the potential to produce enough battery cells to supply more than 10 million electric vehicles per year in 2030.

That is the scale of commitment needed if the U.S. is going to tackle climate change and meet its new auto emissions standards announced in March 2024.

The challenge: These battery factories, and the electric vehicles they equip, are going to require a lot of electricity.

Producing enough battery cells to store 1 kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity – enough for 2 to 4 miles of range in an EV – requires about 30 kWh of manufacturing energy, according to a recent study.

Combining that estimate and our tracking, we project that in 2030, battery manufacturing in the U.S. would require about 30 billion kWh of electricity per year, assuming the factories run on electricity, like the one in Kansas. That equates to about 2% of all U.S. industrial electricity used in 2022.

Battery belt’s huge solar potential

A large number of these plants are planned in a region of the U.S. South dubbed the “battery belt.” Solar energy potential is high in much of the region, but the power grid makes little use of it.

Our tracking found that three-fourths of the battery manufacturing capacity is locating in states with lower-than-average renewable electricity generation today. And in almost all of those places, more demand will drive higher marginal emissions, because that extra power almost always comes from fossil fuels.

However, we have also been tracking which battery companies are committing to powering their manufacturing operations with renewable electricity, and the data points to a cleaner future.

By our count, half of the batteries will be manufactured at factories that have committed to sourcing at least 50% of their electricity demand from renewables by 2030. Even better, these commitments are concentrated in regions of the U.S. where investments have lagged.

Some companies are already taking action. Tesla is building the world’s largest solar array on the roof of its Texas factory. LG has committed to sourcing 100% renewable solar and hydroelectricity for its new cathode factory in Tennessee. And Panasonic is taking steps to reach net-zero emissions for all of its factories, including the new one in Kansas, by 2030.

More corporate commitments can help strengthen demand for the deployment of wind and solar across the emerging battery belt.

What that means for US electricity demand

Manufacturing all of these batteries and charging all of these electric vehicles is going to put a lot more demand on the power grid. But that isn’t an argument against EVs. Anything that plugs into the grid, whether it is an EV or the factory that manufacturers its batteries, gets cleaner as more renewable energy sources come online.

This transition is already happening. Although natural gas dominates electricity generation, in 2023 renewables supplied more electricity than coal for the first time in U.S. history. The government forecasts that in 2024, 96% of new electricity generating capacity added to the grid would be fossil fuel-free, including batteries. These trends are accelerating, thanks to the incentives for clean energy deployment included in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act.

Looking ahead

The big lesson here is that the challenge in Kansas is not the battery factory – it is the increasingly antiquated electricity grid.

As investments in a clean energy future accelerate, America will need to reengineer much of its power grid to run on more and more renewables and, simultaneously, electrify everything from cars to factories to homes.

That means investing in modernizing, expanding and decarbonizing the electric grid is as important as building new factories or shifting to electric cars.

Investments in clean energy manufacturing will play a key role in enabling that transition: Some of the new advanced batteries will be used on the grid, providing backup energy storage for times when renewable energy generation slows or electricity demand is especially high.

In January, Hawaii replaced its last coal-fired power plant with an advanced battery system. It won’t be long before that starts to happen in Tennessee, Texas and Kansas, too.

James Morton Turner is a professor of Environmental Studies at Wellesley {Mass.} College. He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.