Stephen J. Nelson: Painful lessons in college leadership: Dartmouth College and the University of Florida

Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse, soon to be president of the University of Florida, speaking at the 2015 Conservative Political Action Conference, a right-wing Republican event.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In April 1981, David McLaughlin was named the 14th president of Dartmouth College. Though separated by four decades, there are striking similarities between Dartmouth’s appointment of McLaughlin and the University of Florida’s selection last week of its next president, Ben Sasse. If the past is prologue, Sasse and Florida are in for a rough ride.

McLaughlin was an alumnus of Dartmouth, both as an undergraduate and subsequently with an MBA from the Tuck School. While not from the Senatorial arena of Sasse, McLaughlin was a highly political animal. Dartmouth’s choice of him as president came at a moment for the college when disaffected conservative alumni were outraged about racial diversity and the opening of their male bastion to women. McLaughlin’s conservative politics and his purported fiscal belt-tightening reputation and presumed budgetary savvy as a corporate CEO at Champion Paper and Toro Corporation were thought by supporters to be great assets.

The conservative student newspaper, the Dartmouth Review, was about a year old. Conservative alumni, led by monied outside supporters, were opening their wallets and clamoring for more of the contentious voice of the Review. McLaughlin was expected to appease those forces. He promised reinstating ROTC, which had sat dormant for over a decade dating to when the faculty, in the heat of the Vietnam War, cut Dartmouth’s academic ties to the program. Conservative alumni and students cheered his arrival. McLaughlin was to be the fixer for conservative complaints about a new progressive Dartmouth—minorities, women and other changes—that they could not stand.

Sasse carries into his presidential tenure similar conservative baggage. His supporters have grand hopes that he will use the cudgels for which he is famous in the world of politics—decrying gay marriage, advocating overthrow of the Affordable Care Act, and being against abortion—to instill his social brand and edge into the culture of the university. He claims that will not be the case. But given his undeniable high-profile public positions on gay and lesbian issues and rights, abortion, healthcare, affirmative action and the MAGA agenda, the idea that Sasse will change his stripes and that his conservative political bent will now somehow disappear strains credulity and credibility.

As part of his welcome to the campus, the University of Florida faculty have already voted no confidence in the board’s selection process, a tantamount rejection of how and why Sasse was appointed in the first place. Again, if the Dartmouth experience with McLaughlin is any gauge, this vote is only the first salvo in what will be a continuing debate about Sasse as a university president.

From the outset of McLaughlin’s appointment, the Dartmouth faculty, like their Florida counterparts, voiced immense skepticism about the board’s process that resulted in his selection. In the introductory open public faculty meeting that April 1981—I was in the room, then a student affairs administrator—McLaughlin was greeted by pointed criticism from Dartmouth professors. They questioned his capacity to lead in a college and academic culture that was the antithesis of his exclusive corporate sector autocratic and top-down experience. Several faculty members railed to his face about his glaring lack of academic credentials—an MBA, but no Ph.D.—about having no experience teaching and leading a college, bringing only business experience that would never translate to being Dartmouth’s voice in the presidential pulpit.

There was no vote of no confidence in the trustees at the time of their decision. That came four years later dressed in the garb of the unprecedented impaneling of a committee to review McLaughlin’s performance as president. But the Dartmouth faculty restiveness and fear was unmistakable. Their misgivings and judgment that day were born out in a tumultuous, contentious and divisive presidential tenure marked by aggressive, vindicative grudge-based senior administrative turnover, duplicitous leadership, e.g., saying one thing to one group or individual and then the direct opposite to someone else, and a divide-and-conquer style that pitted campus constituencies against each.

For many observers, the Sasse and McLaughlin appointments are sadly only grasped as institutional overreach designed to satisfy certain constituents, rather than aspiring to the greater good of the entire university. McLaughlin lacked fundamental leadership abilities in a president of a college or university. As Sasse assumes the presidency of the University of Florida, there are eerie parallels to Dartmouth’s experience more than 40 years ago. This reality dictates that the Florida faculty must be robust in their scrutiny of how Sasse carries himself, the decisions and actions he takes and his leadership of their university community and its culture. Based on the experience of McLaughlin at Dartmouth, that means the Florida faculty must be vigilantly tuned in to what goes on in the who’s and why’s of senior leadership turnover and new appointments and to kneejerk tendencies to favor conservative causes and to support conservative over liberal professors, student groups and leaders. They must also be attentive to any fiscal and fundraising sleight-of-hand and abuse of the books to make the president look successful.

What is always essential in the leadership of America’s colleges and universities is the naming of presidents who possess critical capacities and commitments: moral grounding, the broad center of understanding and the intellectual gravitas essential in the quest to engage academic communities in the forthright pursuit of intellectual inquiry, freedom of ideas and discourse, and the common good.

Worthy and great college presidents are not accidents or the result of luck. Ill-fitted, ill-suited presidents can do great damage. Early glimmers of what is in the offing reveal what the path might be. Sasse, his faculty and all the constituencies of the University of Florida are on a precipice.

They should look at what happened at Dartmouth in the 1980s, when pressures for conservative, return to a bygone era leadership overwhelmed common sense calling for an academically, intellectually and balanced credible presidential appointment, one truly fit for the complexities and diverse voices in a university community. At Dartmouth, McLaughlin’s selection sorely damaged the esprit de corps of administrative staff, eroded \ the stature and public image of the college and caused a corrosive cynicism in the campus community about its culture. The realities of such presidencies should make all wary indeed.

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and Senior Scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. He is the author of the recently released book, John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College: The Man, the Times, and the College Presidency. His forthcoming book, Searching the Soul of the College and University in America: Religious and Democratic Covenants and Controversies, will be released in 2023. Nelson served on the student-affairs staff at Dartmouth College from 1978 to 1987.

Stephen J. Nelson: Of visionary John Kemeny and decades of court battles over affirmative action at colleges

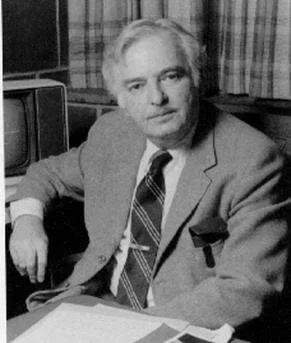

John G. Kemeny (1926-1992), Hungarian-born mathematician, computer scientist and president of Dartmouth College in 1970-1981

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The U.S. Supreme Court is taking up affirmative action at colleges and universities for the sixth time in 50 years. In that litany, an early case was the University of California vs. Bakke. Bakke complained about being denied admission to the university’s medical school because seats were guaranteed for minority applicants, thus barring the door to him and other white applicants.

When the Bakke case was on the court’s docket, John Kemeny was president of Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. The Dartmouth board of trustees wanted a public statement by the college on Bakke. Given their strong confidence in Kemeny, they gave him sole authority to craft Dartmouth’s stand on affirmative action. Kemeny’s voice from his bully pulpit into the public square about the Bakke case echoes today.

Kemeny’s argument displays ahead-of-the-curve insights. His major concern, one still very much at stake in the outcome of the court’s deliberations today, was that colleges had to be able to maintain their fundamental purposes in the face of any court judgment. Should the court mandate a cookie-cutter approach for college admissions, the unintended consequence would be to reduce diversity among institutions of higher education something that Kemeny said simply would be “highly undesirable.”

Using Dartmouth’s example, Kemeny underscored that the board had affirmed the college’s purpose as “the education of men and women with a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society.”

The board did not define that purpose as “the education of students who have the ability to accumulate high grade-point averages at the College,” a statement that would be “ludicrous!”

Kemeny pushed back against the court going over the edge if it were to compel colleges and universities exclusively to use test scores and presumed objective measures to decide which students to admit. That legal edict would restrict colleges from recruiting and admitting musicians, athletes and any student uniquely qualified to contribute to a student body and a college. Quotas of any sort were in his judgment “abhorrent.” Beware what you wish for.

Years after Bakke, in the 2003 University of Michigan cases, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor asserted that colleges had roughly 25 more years to solve their equity and equal-opportunity problems. After that time, reliance on affirmative-action policies would run out. O’Conner’s clock continues to tick.

Getting to where she urged has proved difficult. Progress on the diversity front in the Ivory Tower is glacial and complicated because competing interests must be addressed and give their blessing or at least not actively resist new programs and initiatives. More time than O’Conner predicted is clearly needed. Ideological players on all sides agree that substantive changes in fairness and equity is the arrival point, though there will always be huge differences about the roadmap.

Greater diversity at colleges and universities makes their campus communities more engaging, more demanding, more rewarding and their members more fully educated. Absent diversity, the highest values of what we want a college education to be will remain outside our grasp. That is true for our body politic inside and outside the gates as graduates take their places in the social of communities and the nation. This picture is the goal, but how to get there and how long it will take are the great unknowns.

The new challenge brought by Students for Fair Admissions alleges that Harvard University discriminates against Asian-American students and the University of North Carolina discriminates against white and Asian- American applicants by continuing the use of race as an upfront criteria in admissions rather than observing a race-blind approach that would place more credence and consideration on an applicant’s struggles with discrimination in their life experiences.

The Supreme Court, of course, relies on arguments. The presidents of our colleges and universities must as a group get in the arena, present their case and gather defenders in amicus briefs. The cards will fall as the court dictates. However, jousting over what the Justices will say has to be embraced. It must be made clear to the court’s justices that they must not do harm to hard-fought policies designed to make our colleges and universities equitable, fair and open to diverse populations. Confining latitude and judgments about the scope of admissions procedures and aspirations to add greater diversity to their student bodies would rob colleges and universities of the very autonomy and freedom in their affairs that makes us the envy of the world. The shape of the future of diversity at our colleges is at stake and college presidents must weigh in with all the authority they can muster.

The voices of college presidents have to be front and center in this debate and in the court’s verdict. John Kemeny’s wisdom is a mantle that today’s presidents and those of us concerned diversity and equal opportunity on our campus must take up.

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and senior scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. He is the author of the recently released book, John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College: The Man, the Times, and the College Presidency. He has written several NEJHE pieces on the college presidency.

Stephen J. Nelson: Trying to keep ideological chains out of colleges

The lively experiment that is the college and university in America is characterized by sustained struggles and tempered triumphs that have both undergirded and challenged the fundamental foundation of the academy. The economist and philosopher Kenneth Minogue conveyed in his bookThe Concept of the University that the university can and should allow ideologies to be debated within its gates. However, ideologies cannot be permitted to gain a foothold of control.

Those with political agendas, desires for social reform or other civic interests—no matter how principled or valuable to society—cannot be allowed to shape the university in that image and to those ends. If that happens, the university is no longer the university, but rather a wholly different institution—more a political party, a social action agency or a public policy think tank.

Large questions shape the framework of the academy in America. These include: ideological and the degree to which there should be restrictions and if so what kind on speech and behavior, curricular debates and the expression and treatment of political views, whether exercised by presidents in the bully pulpit, by faculty and students, or by those given the platform to speak on campus.

All in all, the contemporary college and university environment is at least as politicized and ideologically driven as at any time in its history, if not more so. The big question is how the college or university can maintain the fundamental identity at the foundation of its heritage in the face of ideologies that would pull it willy-nilly in one direction or the other, and bend it to the expediency of their competing and mutually exclusive points of view.

The college and university is a complex entity, in many ways an organism with interlocking, related but independent parts. Many within its gates, and certainly many critics on the outside, do not fully comprehend and appreciate how fragile the academy is. Though reductionist regarding the political winds and sways in today’s academy, the forces on today’s neo-conservative Right seek preservation, maintenance of the traditions and traditional curriculum and culture of the academy. Those on the progressive Left seek the transformation of society, the use of the college and university for egalitarian, social justice and minority-advancement ends.

Political correctness critics on the Right believe that there exists a lock exerted by the Left in all aspects of campus and student life, and a dangerous domination of the Left’s political agenda in both administrative and faculty appointments and ranks. These critics are certain that colleges and universities are shot through with litmus tests, and are bound and determined unalterably to stamp their political leanings and convictions not only within campuses, but infiltrating society and the nation as well.

In the face of these charges, the Left has pushed back using their own contending tropes. They deny these accusations. The Left is not monolithic. It features many slices and shades of individual differences. The criticisms of the Left are unfair, often ad hominem (which in many cases they are). As one example, the Dartmouth Review ran a headline in the early days of the tenure of Dartmouth President James Freedman, a Jew that read, “Ein Reich, Ein Volk, Ein Freedman,'' with the allegation that he and Dartmouth were rounding up conservatives on campus and putting them on trains in White River Junction, Vt.

However, these dueling perspectives and allegations prompt crucial questions. What if the roles of Left and Right were reversed and the shoe was on the other foot? In going about their business and using their leverage to shape the culture of the academy, is the liberal, progressive Left ignoring the legacy that their influence will surely leave behind?

In other words, if Leftists in the academy are indeed dominant and able to get their way, what would happen if they were on the outside looking in? What if they were consigned to the minority position with little power? What ammunition would they in turn use in the climb to reclaim territory? Wouldn’t they likely throw at their enemies on the Right what the Right now throws at them?

Playing willy-nilly with the core principles and values—a commitment to unfettered inquiry, free speech and expression of idea, a journey to be as objective as possible, and judgments made about ideas, not on the basis of political axes to grind—of the university is an extremely dangerous game. Its effect erodes the foundations of the academy and creates the prospect that what is wrought can come back to bite you.

This is “the shoe is on the other foot” conundrum. Surveying this scene, the late philosopher Ron Dworkin used “an old liberal warning. But it is a warning that cannot be repeated often enough.” That warning and the fear about the damage it does to academic freedom is that “Censorship will always prove a traitor to justice.” The late cultural critic Edward Said, a colleague of Dworkin at Columbia, claimed the antidote to foundational principles of the university being sacrificed on the scaffold of dueling political parties parading ideological points of view is in Cardinal Newman’s idea that “intellectual culture” constitutes the foundation of the university.

Over the past four decades, a number of critical issues and events have shaped the college and university. What have we come to today?

Donald Downs, a University of Wisconsin historian and observer experienced in the academy, notes that when the “right not to be offended” is exploited and trumps everything else in the arena of free speech and academic freedom, a double whammy results. This is precisely the problem that critics of political correctness decry: that the actions of colleges and universities become overwrought in an effort to placate the complaints of the minority. The result: The creed of the academy is eroded and the interests of the majority of its constituents are thwarted and suppressed.

Downs is concerned that we can never lose our commitment in the academy to free and open debate. Among other things, this means academicians and university leaders must exert enormous care as they assess what should be considered “in” versus what is considered “out” in curriculum, in the courses professors teach, in who is invited and permitted to speak on campus, and in how the university ensures free discussion and dialogue in all its affairs.

In the environment of the academy over the past five or more decades (certainly traceable to the aftermath of World War II and the McCarthy era), critical thinking challenged and criticized longstanding premises, and what were presumed to be established mores, ethical assumptions and beliefs. For many, this critique of society and culture created a vacuum of morality and values.

Into that breach came those demanding moral replacements, often pressing the cause by sheer demagoguery. For example, curricular battles often were reduced to whether American and other Western ideals were being supplanted by more superficial and less fitting set of cultural norms that were designed to undermine and erode the political philosophies and governing assumptions of the tested Western traditions. Both sides of the political correctness divide have made careers out of presenting themselves as the saviors to fill this vacuum, and to fix a society and academy that is in disarray and lacks moral fiber and moral compass.

The mores, debates and controversies, particularly in the 1960s and early 1970s, jumpstarted and stirred up ideological thinking. Social and political culture provided new grist for the mills of advocates for competing positions and to the coining of the term political correctness. The danger to the university became ever more clear: When the university caves to political correctness and tilts to being a social, political and cultural institution of change, it loses its identity as the university.

Maintaining rational dialogue in the academy across these divides is not a simple task and never has been. As the great thinker and experienced denizen of the Ivory Tower, Isaiah Berlin commented: “Unless we are able to escape from the ideological prisons of class or nation or doctrine, we shall not be able to avoid seeing alien institutions or customs as either too strange to make any sense to us, or as issues of error, lying inventions of unscrupulous priests. …”

The escape route for the academy in America from the confines and bondage of extreme forms of political correctness on one side—and the politically motivated critics of those progressive, leftist agendas on the other—is only through reliance on its foundation: the college and university qua the college and university.

In the battleground between warring political factions of Left and Right, the university has to be a balance wheel, it has to navigate in the middle, refusing to take sides and welcoming all comers. That is after all what it means for the university to be the university. The crucial balancing act is between the tyrannies of both the majority and the minority. Both sides in the political correctness debates would claim the wish to avoid becoming a tyranny of the minority or of the majority. However, both sides shamelessly seek and are more than willing to use this leverage when it is to their advantage and suits their purposes.

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) warned in its 1915 “Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure” about the “’tyranny of public opinion.’” The AAUP added to that admonition declaring in its 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure: “Institutions of higher education are conducted for the common good and not to further the interest of either the individual teacher or the institution as a whole. The common good depends on the free search for truth and its free exposition.”

A major question for the college and university at present and for the future is: Is the tyranny of public opinion worsening or is it simply a longstanding threat that each generation, in and outside the gates, must regularly confront in a democracy?

The college or university always faces the challenge to navigate successfully the choices between tradition and change, and between what can and should be dearly held, and what may need to be jettisoned in light of present and coming demands. Change is inevitable and should not be feared. Historian Jacques Barzun’s counsel provides context: We should “ask why that same phenomenon [that things are getting worse] recurs; in other words, the historical-minded should look into the meaning and cause of the undying conviction of decline. One cause, one meaning, is surely that in every era some things are in fact dying out and the elderly are good witness to this demise.”

The formation of the academy in America is a distinctive saga, unique to the American Republic and how it has been shaped and formed since its very beginnings and Colonial college roots. This saga demands continual reexamination and revisiting in every generation and in every era. It is a saga that endures. It is a history that only when we are able to get our arms around it and to gather a firmer grasp of it, are we able to have a more enlightened and nuanced sense for the story of the shape and shaping of the college and university in America.

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and senior scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. His most recent book, College Presidents Reflect: Life in and out of the Ivory Tower, was released in 2013. His forthcoming book, The Shape and Shaping of the College and University in America: A Lively Experiment (Rowman and Littlefield, Lexington Books) will be released in March. This commentary originated in the New England Journal of Higher Education, part of the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org).