Slow, but no fossil-fuel emissions!

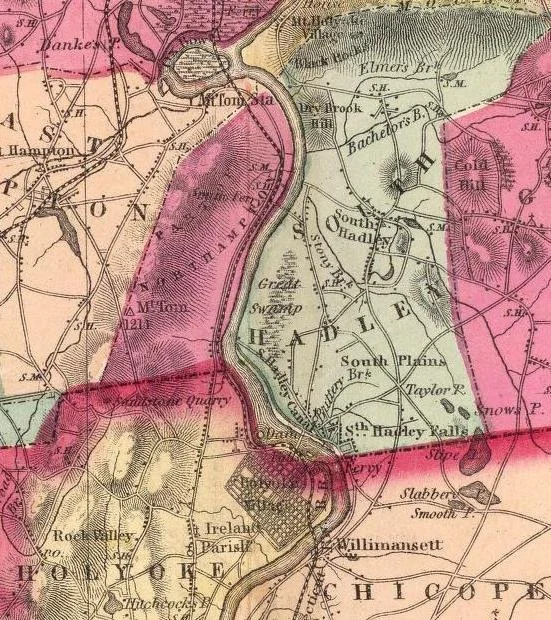

Map of South Hadley Canal, the earliest such commercial canal in the U.S. It was opened in 1795 and was closed in 1862 because of competition from railroads.

Timothy Dwight (1752-1817), who served as president of Yale (1795-1817), traveled through New England and New York beginning in the 1790s. The first volume of his four-volume account of his travels included this description of the South Hadley (Mass.) Canal.

About five or six miles above Chequapee [Chicopee] we visited South Hadley Canal. Before this canal was finished, the boats were unloaded at the head of the falls, and the merchandise embarked again in other boats at the foot.

The removal of this inconvenience was contemplated many years since, but was never seriously undertaken until the year 1792, when a company was formed, under the name of the proprietors of the locks and canals in Connecticut river, and their capital distributed into five hundred and four shares. . . .

A dam was built at the head of the falls, following, in an irregular and oblique course, the bed of rocks across the river. The whole height of the dam was eleven feet, and its elevation above the surface, at the common height of the stream, four. Its length was two hundred rods.

Just above the dam the canal commences, defended by a strong guard-lock, and extends down the river two miles and a quarter. At the lower end of the canal was erected an inclined plane. . . .

The outlet of the canal was secured by a sufficient lock, of the common construction. When boats were to be conveyed down the intended plane, they passed through the lower lock, and were received immediately through folding doors into a carriage, which admitted a sufficient quantity of water from the canal to float the boat. As soon as the boat was fairly within the carriage, the lock and the folding-doors were closed, and the water suffered to run out of the carriage through sluices made for that purpose. The carriage was then let slowly down the inclined plane. . . .

The machinery, by which the carriage was raised or lowered, consisted of a water-wheel, sixteen feet in diameter, on each side of the inclined plane; on the axis of which was wound a strong iron chain, formed like that of a watch, and fastened to the carriage.

When the carriage was to be let down, a gate was opened at the bottom of the canal; and the water, passing through a sluice, turned these wheels, and thus slowly unwinding the chain, suffered the carriage to proceed to the foot of the plane by its own weight. When the carriage was to be drawn up, this process was reversed. The motion was perfectly regular, easy, and free from danger. . . .

From Travels in New England and New York, Volume1, by Timothy Dwight

Remnant of the canal

Elizabeth Markovits/Amber Douglas: Pandemic innovation at Mount Holyoke College

The main gate of Mount Holyoke College, in the college-rich Connecticut River Valley.

From The New England Board of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Students choose small liberal arts colleges for the learning that unfolds when they are deeply immersed in intellectual collaboration with faculty and with one another. The photos that festoon our promotional materials aren’t mere marketing—we spend a lot of time with one another in close quarters. Faculty and staff are truly invested in student success, working creatively to develop exceptional experiences for our students.

Students themselves collaborate deeply both inside and outside classroom environments, facilitated by a high-density, residential campus. We do this work with the goal of helping the next generation develop the critical thinking and communication skills they need to excel for the rest of their lives—skills that seem more important with each passing day.

So how is that model going to work now when the name of the game is social distancing?

While at times, the challenge of delivering the educational experience for which we are known has seemed insurmountable, on our campus, a practical, flexible new model has begun to emerge—one built around a clear understanding of exactly who our students are, the issues they’ll face this fall, and the near certainty that the college will need to meet a wide range of different learning contexts. We call it flexible immersive teaching—FIT.

Like other institutions, we hope to return to campus this fall with students in residence. But we already know that not every student will be able to join us in person, whether because of immigration and travel issues or because of health and safety considerations. Like many of our colleagues at other liberal arts colleges, we’ve never been comfortable with the models known as “hybrid” or “hy-flex” learning, and the plans to offer a mixture of in-person and online course options are problematic for us.

Creating distinct paths through the curriculum raises significant concerns around diversity and inclusion. Depending on how students are selected or elect to return to campus in the fall, Hy-Flex models, characterized by offering the students a choice of asynchronous, online learning or real-time synchronous sessions, may reify pathways that fall along social classifications like race and class, exacerbating divisions already deepened by current health and political crises.

Offering a subset of online courses to remote students may mean institutions lose one of their greatest strengths: offering community members the opportunity to learn from one another across difference. Diverse perspectives are essential to learning, now more than ever. We fear that distinct communities, now separated by the pandemic, will result in differentiated learning experiences that undermine the sense of community that so many of us strive to create on campus. We must meet students where they are, in flexible modes, in order to stay true to our mission of inclusive excellence.

On our campus, as we worked through these issues, we listened deeply to faculty, staff and student concerns, including representatives from each of these constituencies in our planning groups. Rather than forging ahead to get back to normal as soon as possible, we listened first. We heard a yearning to return to the sense of intellectual excitement that marks the liberal arts experience—the shared discovery of new authors and conceptual frameworks to help make sense of the world around us as it changes as breakneck speed, the close collaboration between students on an art exhibit for a class, performing choral music for the community, introducing students to robotics workshops in our MakerSpace—but also a concern that workloads were doubling and tripling at a time when faculty had lost childcare, research opportunities and a sense of physical safety in the world.

We heard the need to come up with a model that will allow us to get as many students as possible back on campus—offering students more equal learning contexts and preserving staff jobs—but also a need to protect the health and safety of our community. We also heard from our students that there was significant cognitive drain when they had to switch between so many courses and tools in the emergency remote period.

As we looked at our options, FIT emerged as the best model. We are working to get as many students back into residence as health guidelines and immigration controls will allow. Meanwhile, our curriculum will be designed to work fully in digital formats, accessible to students residing on campus and around the world. However, this is not traditional online teaching, which was designed for working adults to access on their own time and own pace. Instead, we want students to come together in real time to collaborate with one another and faculty, using technology in smart ways to close the distance required by the pandemic.

Our curriculum centers on accessible, robust, active learning to recreate the immersive experience. With the FIT model, we can offer students a rigorous program of intellectually engaged work, collaboration with one another, and direct access to a faculty deeply invested in their success, no matter where they are. As we construct something entirely new, student success and faculty development must be more tightly intertwined than ever.

Mount Holyoke’s FIT model at a glance:

Delivered online to maximize student and faculty accessibility

Emphasis on real-time interaction to ensure immersive experience and inclusion for all students Modular semester: two 7.5-week modules to allow students and faculty to focus more deeply on each course

Classes take place between 8 a.m. and 10:30 p.m. to accommodate students abroad.

This is a radical change—and it’s not easy. In our case, we have already upended a great deal of how we normally operate.

In May, our faculty voted to adopt a modular system of two 7.5-week modules per semester. Taking the traditional 4-5 courses at the same time in these new formats, in environments marked by home distractions or 12-hour time differences, represents a huge additional cognitive load for students and we are too committed to their success to set them up for an unnecessary additional burden.

We’re using a broader expanse of hours in a day—from 8 a.m. to 10:30 p.m.—to ensure that students who live abroad can access our curriculum and to improve social distancing on campus. The modular semester with a reimagined daily schedule allows for students to elect individualized pathways in concert with their learning environments, but always in community with their fellow students.

Within the FIT model, these structural changes are married with innovative pedagogical practices that will enable faculty to respond to the emergent changes and events that affect student learning, fostering resiliency and continued growth and learning in our students. The adaptability of this approach allows us to be responsive to the uncertainty to come, whether in response to COVID, the upcoming national election or whatever else comes our way. The fall, indeed the coming academic year, cannot be business as usual. To act as if things have not changed sets students and faculty alike for disappointment and frustration.

We are also making significant investments in educational technology and asking everyone on campus to learn new tools and work with new materials. Reimagining classes in digital formats means re-designing from the ground up in many cases, putting the learning goals at the center, rather than a demand to be in-person. For example, if we can’t all be together in person or work together without masks and physical distance, what does it mean to grow as a lab scientist? As a violist in an orchestra? As an actor in a theater program? As a new student learning a language for the first time? We have been inspired and encouraged by our faculty when listening to their ideas and have made investments in the technology tools to facilitate these innovations. These changes require significant commitments from faculty and staff, who are postponing other plans and working through nights and weekends to redesign courses. But we view this level of radical change as absolutely necessary in order to preserve our commitment to the success of each and every student who has chosen Mount Holyoke.

In higher education, we’ve all known that disruptive change is ongoing and inevitable, even if only a year ago, few of us would have anticipated that a global pandemic would be the catalyst. Some colleges and universities will not survive this crisis. Among those that do survive, how will their core principles be affected? Which will endure, which will change and which will be jettisoned entirely?

We believe those that emerge with their principles intact are best prepared to lead in the future. At Mount Holyoke, we know exactly what makes our model special, and we’re undertaking the hard, sometimes painful, work of preserving it, even as the modes of delivery have changed dramatically.

Ultimately, we’re doing exactly what we work so hard to prepare students to do in the world long after they graduate: Be flexible, be resilient and stay true to their principles.

Elizabeth Markovits is director of the Teaching & Learning Initiative and a professor of politics at Mount Holyoke College, in South Hadley, Mass. Amber Douglas is dean of studies and associate professor of psychology at Mount Holyoke.