Frank Carini: Brockton's water use threatening region's environment

By FRANK CARINI

In late October of last year, the water level of Silver Lake, in the Brockton, Mass., area, was down 72 inches, or 6 feet. Three weeks later, in mid-November, the level had dropped another 8 inches. Large portions of Massachusetts remain under drought conditions, but Alex Mansfield and Pine duBois of the Jones River Watershed Association claim the lake’s demise is a preventable manmade crisis.

They and others blame the problem on decades of overuse and misuse of local and regional waters. The city of Brockton, for instance, takes about 10 million gallons daily out of Silver Lake and pumps it 20 miles through two pipes, one of which is more than 100 years old.

The water level of 640-acre Silver Lake, which touches three Massachusetts communities, Pembroke, Kingston and Plympton, is at a 30-year low, according to Mansfield. He said this fact shouldn’t surprise anyone. In fact, both he and duBois say it’s long been known that Silver Lake can’t sustain that amount of daily withdrawal. It can’t even sustain half the current daily allotment, according to duBois.

Mansfield said the city of Brockton tracks the lake’s water level and water quality daily. ecoRI News spoke with Mansfield and duBois on the evening of Jan. 4. They said Silver Lake’s water level was down another foot and a half from mid-November.

“This issue doesn’t have anything to do with drought,” Mansfield said. “It’s about the city taking too much water. And the thing is we haven’t seen anything close to the worst of it. We’re starting 2017 at a 30-year low, and it’s so low that the lake isn’t going to rebound by April. That’s a bad starting point.”

Silver Lake, which lies within the Jones River watershed, is the 12th-largest natural lake in Massachusetts. When substantially drained, many additional feet of lakebed are exposed, and slow-moving animals, most notably freshwater mussels that clean the lake water of nutrients, can’t keep up with the receding shore and die.

Mansfield said the current crisis has killed fish, turtles and “tens of thousands” mussels. He also noted that people are riding their ATVs around the dry lakebed.

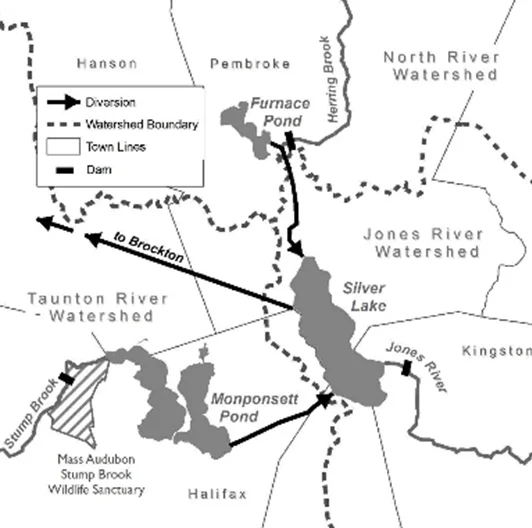

The city of Brockton gets its water from Silver Lake and several ponds in the surrounding area. (Mass Audubon)

The pumping of Silver Lake and other area waterbodies to meet Brockton’s water needs is impacting water quality and wildlife habitat from Halifax to Cape Cod, according to the Jones River Watershed Association (JRWA). Both Tubbs Meadow Brook, Silver Lake’s largest inflow, and Mirage Brook, a sub-watershed that makes up 25 percent of Silver Lake’s watershed, are stressed, according to the Kingston-based organization.

“The city of Brockton couldn’t care less,” said Mansfield, noting that the city is still negotiating a consent order with the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). “They continue to say there’s no problem.”

In a Jan. 5 e-mail to ecoRI News, Larry Rowley, Brockton’s Department of Public Works commissioner, wrote that the city is “still in negotiations with DEP on this issue so no one should be discussing anything about this. When we have a final agreement we would be happy to talk to you.”

The city of Brockton began pumping water from Silver Lake in 1904. Several times during the next five decades the city was encouraged to find additional sources, or likely face water shortages. The advice was ignored.

In 1964, Brockton and the lake’s surrounding communities got a first-hand look at the predicted impact, when Silver Lake was drawn down by more than 8 feet, like it is now. The city had to stop drawing water from the lake for several months. The crisis prompted the creation of a special commission to find Brockton more water.

The commission’s report found that Silver Lake couldn’t supply more than 4.5 million gallons daily. Despite local opposition, however, the report eventually lead to an emergency legislative action that allowed Brockton to divert water from Monponsett Ponds in Halifax and Furnace Pond in Pembroke into Silver Lake, to expand the city’s water supply.

The decision to increase Brockton’s regional water withdrawals — the JRWA says 11 million gallons a day from all sources is the recommended limit — has had an adverse impact on the environment, according to Mass Audubon.

Among those impacts, according to the organization, are: lack of flow to Jones River, from Silver Lake, Stump Brook, from Monponsett Ponds, and Herring Brook, from Furnace Pond, during significant periods of the year; severe drawdown of Silver Lake for months at a time every year; habitat for fish and other aquatic life in local waterways is severely degraded, and in some cases eliminated for months at a time; and both Monponsett Ponds and Furnace Pond both have excessive-nutrient problems.

The special commission also suggested that connecting Brockton to the Metropolitan District Commission — now the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) — water supply would be the better solution, But it was decided that such an effort would take too long to address the existing emergency.

A decade later, in 1974, a consulting firm was hired to examine the city’s existing water supplies and needs. It determined that Brockton still didn’t have enough water to survive a drought. Nothing was done. In both 1982 and ’86, Massachusetts had to enact water-supply emergencies because Brockton had drawn Silver Lake down by as much as 20 feet.

A search began for more water. Connecting to the MWRA water supply was again recommended. The idea was again ignored. Instead, a desalination plant was built on the western banks of the Taunton River in Dighton. The facility takes water from the lower part of the Taunton River and purifies it to drinking-water standards.

Since the Aquaria Desalination Plant went on-line in 2008 it has supplied Brockton with about 3 percent of its annual water needs. Last year, the plant supplied less than 7 percent of the city’s water.

Mansfield said Brockton has never made the switch to MWRA water because of cost. “It’s more expensive than taking water out of the lake,” he said. “The desalination plant is barley used because the city doesn’t want to get locked into using it.”

The MWRA was established by an act of the Legislature in 1984 to provide wholesale water and sewer services. Today, the agency serves some 2.5 million people and more than 5,500 large industrial users in 61 cities and towns.

The 1964 Legislative act didn’t include any protections for Silver Lake, but it did include protections for Monponsett and Furnace ponds. The act set limits on when water can be diverted: no diversions in the summer when there are recreational uses; no diversions when the ponds are low; and no diversions when water quality presents a public-health risk, for example.

These important protections mean these additional water supplies aren't always available. Monponsett Ponds have been suffering from poor water quality for more than year. Excessive nutrient loading, lack of flushing and other problems have led to blooms of potentially toxic cyanobacteria. In fact, cyanobacteria cell counts have been measured in the millions per milliliter, far exceeding the public-health standards for swimming, according to the DEP.

The DEP has found that the nutrient levels of Monponsett Ponds, most notably West Monponsett Pond, are more than 300 times what they should be, which is fueling the cyanobacteria blooms.

Silver Lake also has spent time on the Massachusetts impaired waters list, for “fish, other aquatic life and wildlife,” according to DEP. The Jones River, which flows out of Silver Lake, is impaired in terms of “aesthetics, fish and wildlife, and recreational contact.” The river’s specific impairments include low dissolved oxygen and excess algae growth. DEP cites “flow alterations from water diversions” as the reason for these impairments.

“The quality of the ponds that go into Silver Lake have been degraded,” Mansfield said. “Bacteria blooms, swimming bans, no pets in the water. The entire arrangement has caused water-quality problems.”