Of Harvard, Summers, Russia and the future

The Kremlin

— Photo by A.Savin

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Some years ago, I set out to write a little book about Harvard University’s USAID project to teach market manners to Boris Yeltsin’s Russian government in the 1990s. The project collapsed after leaders of the Harvard mission were caught seeking to line their own pockets by gaining control of an American firm they had brought in to advise the Russians. Project director Andrei Shleifer was a Harvard professor. His best friend, Lawrence Summers, was U.S. assistant Treasury secretary at the time.

There was justice to be served. The USAID officer who blew the whistle, Janet Ballantyne, was a Foreign Service hero. The victim of the squeeze, John Keffer, of Portland, Maine, was an exemplary American businessman, high-minded and resourceful.

But I had something besides history in mind. By adding a chapter to David McClintick’s classic story of the scandal, “How Harvard Lost Russia,’’ in Institutional Investor magazine in 2006), I aimed to make it more complicated for former Treasury Secretary Summers, of Harvard University, to return to a policy job in a Hillary Rodham Clinton administration.

It turned out there was no third Clinton administration. My account, “Because They Could, ‘‘ appeared in 2018. So I was gratified last August when, with the presidential election underway, Summers told an interviewer at the Aspen Security Forum that “My time in government is behind me and my time as a free speaker is ahead of me.” Plenty of progressive Democrats had objected to Summers as well.

Writing about Russia in the1990s meant delving deeper into the history of U.S.-Russia relations than I had before. I developed the conviction that, during the quarter century after the end of the Cold War, U.S. policy toward Russia had been imperious and cavalier.

By 1999, Yeltsin was already deeply upset by NATO expansion. The man he chose to succeed him was Vladimir Putin. It wasn’t difficult to follow the story Through Putin’s eyes. He was realistic to begin with, and, after 9/11, hopeful (Putin was the among the first foreign leaders to offer assistance to President George W. Bush).

But NATO’s 2002 invitation to the Baltic states — Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — all former Soviet Republics, the U.S .invasion of Iraq, the Bush administration’s supposed failure to share intelligence about the siege of a school in Beslan, Russia, led to Putin’s 2007 Munich speech, in which he complained of America’s “almost uncontained hyper use of force in international relations.”

Then came the Arab Spring. NATO’s intervention in Libya, ending in the death of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, was followed by Putin’s decision to reassume the Russian presidency, displacing his hand-picked, Dimitri Medvedev, in 2012. Putin blamed Hillary Clinton for disparaging his campaign.

And in March 2014, Putin’s plans to further a Eurasian Union via closer economic ties with Ukraine having fallen through, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych fled to Moscow in the face of massive of pro-European Union demonstrations in Kyiv’s Maidan Square. Russia seized and annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula soon after that.

The Trump administration brought a Charlie Chaplin interlude to Russian-American relations. Putin saw no problem: He offered to begin negotiating an anti-hacking treaty right away. Neither did Trump: Remember Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s Oval Office drop-by, the day after the president fired FBI Director James Comey?

Only the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal, among the writers I read, seemed to think there was nothing to worry about in Trump’s ties to Russia. Meanwhile, Putin rewrote the Russian Constitution once again, giving himself the opportunity to serve until 2036, when he will be 84.

But Russia’s internal history has taken a darker turn with the return of Alexander Navalny to Moscow. The Kremlin critic maintains that Putin sought his murder in August, using a Soviet-era chemical nerve-agent. Navalny survived, and spent five months under medical care in Germany before returning.

Official Russian media describe Navalny as a “blogger,” when he is in fact Russia’s opposition leader. He has been sentenced to at least two-and-a-half years in prison on a flimsy charge, and face other indictments. But his arrest sparked the largest demonstrations across Russia since the final demise of the Soviet Union. More than 10,000 persons have been detained, in a hundred cities across Russia, according to Robyn Dixon, of The Washington Post. Putin’s approval ratings stand at 29 percent

What can President Biden do? Very little. However much Americans may wish that Russian leaders shared their view of human rights, it should be clear by now there is no alternative but to deplore, to recognize Russian sovereignty, to encourage its legitimate business interests, discourage its trickery, and otherwise hope for the best. There are plenty of problems to work on at home.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this columnist first appeared.

David Warsh: What went wrong in Epidemiologists’ War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is clear now that United States has let the coronavirus get away to a far greater extent than any other industrial democracy. There are many different stories about what other countries did right. What did the U.S. do wrong?

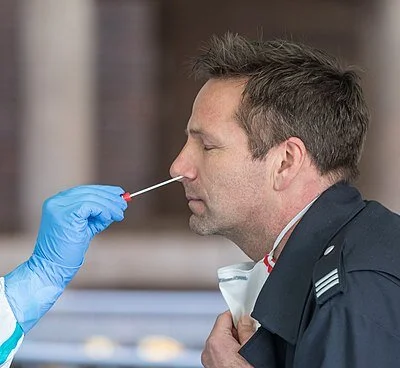

When the worst of it is finally over, it will be worth looking into the simplest technology of all, the wearing of masks.

What might have been different if, from the very beginning, public health officials had emphasized physical distancing rather than social distancing, and, especially, the wearing of masks indoors, everywhere and always?

Even today, remarkably little research is done into where and how transmission of the COVID-19 virus actually occurs – at least to judge from newspaper reports. Typical was a lengthy and thorough account last week by David Leonhardt, of The New York Times, and several other staffers.

Acknowledging that previous success at containing viruses has led to a measure of overconfidence that a serious global pandemic was unlikely, Leonhardt supposed that an initial surge may have been unavoidable. What came next he divided into four kinds of failures: travel policies that fell short; a “double testing failure”; a “double mask failure”; and, of course, a failure of leadership.

The American test, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which worked by amplifying the virus’s genetic material, required more than a month longer to be declared effective, compared to a less elaborate version developed in Germany. The U.S. test was relatively expensive, and often slow to process. The virus spread faster than tests were available to screen for it.

As for masks, Leonhardt reported, experts couldn’t agree on their merits for the first few months of the pandemic. Manufactured masks were said to be scarce in March and April. Their benefits were said to be modest.

From the outset it was understood that most transmission depended on talking, coughing, sneezing, singing, and cheering. Evidence gradually accumulated that the virus could be transmitted by droplets that hung in the air in closed spaces – in restaurants, and bars, for example, on cruise ships, or in raucous crowds. By May, it became more common for official to urge the wearing of masks.

But Leonhardt cited no evidence of the rate at which outdoor transmission occurred among pedestrians, runners or participants in non-contact sports. Nor did he take account of wide disparities of distance across America among people in cities, suburbs, and country towns. In many areas, most people used common sense, which turned out to be pretty much the same as medical advice.

Instead of becoming ubiquitous indoors and out, as in Asia, or matters of fashion, as in Europe, Leonhardt wrote, masks in the United States became political symbols, “another partisan divide in a highly polarized country,” unwittingly exhibiting the divide himself.

Whether things would have turned out differently had face-coverings been confidently mandated everywhere indoors from the very beginning, and recommended wherever where crowds were unavoidable, is a matter for further research and debate. Not much is known yet about the efficacy of various forms of “lock-down” – office buildings, public-transit, schools, college dormitories.

This much, however, is already clear: very little effort has been spent on discovering what was genuinely dangerous and what was not; still less on communicating to citizens what has been learned. Epidemiologists live to forecast. Economists conduct experiments. Expect the “light touch” policies of the Swedish government to attract increasing attention.

About the failure of leadership in the U.S., Leonhardt is unremitting: in no other high-income country have messages from political leaders been “so mixed and confusing.” Decisive leadership from the White House might have made a decisive difference, but the day after the first American case was diagnosed, President Trump told reporters, “We have it under control.” Since then consensus has only grown more elusive, at least until recently.

Word War I was sometimes called the Chemists’ War, because of the industrially manufactured poison gas employed by both sides, The German General Staff looked after their war production. World War II was the Physicists’ War,” thanks to the advent of radar and, in the end, the atomic bomb. It was equally said to be the Economists’ War, chiefly because of the contribution of the newly developed U.S. National Income and Product Accounts to war materiel planning.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been the Epidemiologists’ War. Next time look for economists to make more of a contribution. And hope for a more prescient and decisive president.

. xxx

The New York Times reported last week it had added 669,000 net new digital subscriptions in the second quarter, bringing total print and digital subscriptions to 6.5 million. Advertising revenues declined 44 percent. Earnings were $23.7 million, or 14 cents a share, down 6 percent from $25.2 million, or 15 cents a share, a year earlier.The news made the pending departure of chief executive Mark Thompson, 63, still more perplexing.

“We’ve proven that it’s possible to create a virtuous circle in which wholehearted investment in high-quality journalism drives deep audience engagement, which in turn drives revenue growth and further investment capacity,” Thompson said. His deputy, Meredith Kopit Levien, 49, will succeed him on Sept. 8, the company announced last month. Kopit Levien told analysts last week that the company believed the overall market for possible subscribers globally was “as large as 100 million.”

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

David Warsh: Getting beyond despair: Three prongs to address climate change

— By Adam Peterson

Flooding caused by Super Storm Sandy in Marblehead, Mass., on Oct. 29, 2012

From economicprincipals.com

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Weighed down by not knowing what to expect of the coronavirus timetable, I spent a day last week reading about climate change. Specifically, I read Three Prongs for Prudent Climate Policy, by Joseph Aldy and Richard Zeckhauser, both of Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

Paradoxically I came away feeling better. Grim though the situation they describe is, theirs is anything but a counsel of despair.

For three decades, advocates for climate change policy have simultaneously emphasized the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and provided unrealistic reassurances of the feasibility of doing so. It hasn’t worked out, say Alby and Zeckhauser.

The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 imposed binding commitments on industrial nations to reduce emissions below 1990 levels in a decade. They exceeded them. Even so, global carbon dioxide emission grew 57 percent over the same ten years, because developing nations hadn’t joined the accord.

So the Paris Agreement of 2015 established “pledge and review” commitments by from virtually every nation in the world, designed to prevent warming of more than 2 degrees centigrade by 2030. But even if every country honors its pledge, the policy is unlikely to succeed in meeting the target, say Aldy and Zeckhauser,

That’s because what’s already in the atmosphere is a stock, not a flow. From the pre-industrial period to 1990, carbon dioxide concentration increased by about 75 parts per million. Since 1990, CO2 has increased by another 55 parts per million, and despite the agreements, the rate of increase is apparently accelerating.

Meanwhile, global temperature have increased around half a degree centigrade in the last 30 years. They are likely to rise faster in the years ahead. Storms, droughts, floods, fires, melting will increase. Mass migrations in response to these weather events have barely begun.

So, the authors say, after 30 years of single-minded stress on emission reductions in climate change discourse, two other policy prongs are urgently needed.

One of these headings, adaptation, is well-known and uncontroversial, except that it costs a lot in more complicate applications than in simple adjustments. Moving heating plants from basements to upper stories so that equipment is not damaged by flooding is simple and relatively cheap. Sea barriers and storm gates to protect coastal cities are another. The sea wall to protect the Venice lagoon is almost finished, but the Army Corps of Engineers plan to protect New York City would take 25 years to construct.

The other strut, amelioration, is considerably less discussed, mainly for fear of the ease with which the remedy may be embraced, once the cost differences are better understood. “Solar radiation management” means putting a sunscreen into the sky – most likely sulfur particles injected into the upper atmosphere by specially built airplanes. Major volcanic eruptions over the centuries have proven that the principle will work, though myriad details of its practical application are hazy. What’s clear is that so-called “geo-engineering” would cost considerably less than emissions reduction or adaptation, especially if time were of the essence.

The only place I see radiation management brought up regularly in the things I read is in Holman Jenkins’s twice-a-week column in the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal. The other day Jenkins noted Amazon’s Jeff Bezos’s intention to spend $10 billion to fight climate change. Don’t spend it touting nuclear power, Jenkins advised; Bill Gates is already working on that. And never mind carbon taxation; that must come, if it comes, from the Left. Instead, why not atmospheric aerosol research?

Right though Jenkins may be about the possibilities of solar-radiation mitigation, he is preaching to those ready to be converted. That’s why I was interested in the Aldy-Zeckhauser paper: they are several steps closer to the mainstream. Aldy served as the Special Assistant to the President for Energy and Environment in 2009-2010. Zeckhauser works in in the tradition of tough-minded cooperation pioneered by his mentor, the policy intellectual (and Nobel laureate) Thomas Schelling.

But if we can’t handle a virus, what hope is there of devising effective policies against climate change? That’s just the point: we can handle a virus. It just takes a year, or, probably, two. The problem of arresting global warming is much more difficult, but if you believe the science, there can be no doubt that disastrous events will sooner or later cause public opinion around the world to come around

Wisdom begins with the recognition that there are three policy prongs with which to address the problem of greenhouse gases, not just one. Slowing the effects of carbon dioxide emissions – while continuing to slow emissions themselves – turns on the next election, and the two or three elections after that.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

© 2020 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

web design by PISH P