Don’t be a slob, become president

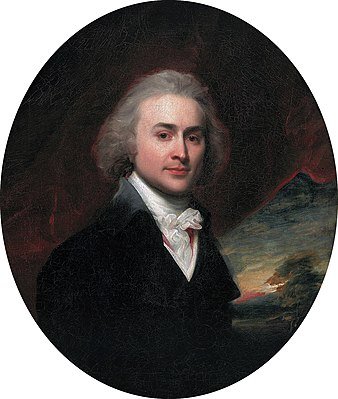

John Quincy Adams as a young man

“You come into life with advantages which will disgrace you if your success is mediocre. And if you do not rise to the head not only of your own profession, but of your country, it will be owing to your own laziness, slovenliness and obstinacy.“You come into life with advantages which will disgrace you if your success is mediocre. And if you do not rise to the head not only of your own profession, but of your country, it will be owing to your own laziness, slovenliness and obstinacy.’’

— Then Vice President (and the next President) John Adams (1735-1826) to his son John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), then a teenager, in 1794. John Quincy Adams managed to become secretary of state, president and congressman, in which job he led the opposition to slavery. Both Adamses are buried at the United First Parish Church, in Quincy, Mass.

Enjoying Quincy’s 19th Century ‘multiplicity of nature’

Still pretty: View looking east on Quincy Bay

— Photo by Sswonk

Quincy, Massachusetts (oil on canvas), by Childe Hassam, 1892

“Winter and summer, then, were two hostile lives, and bred two separate natures. Winter was always the effort to live; summer was tropical license. Whether the children rolled in the grass, or waded in the brook, or swam in the salt ocean, or sailed in the bay, or fished for smelts in the creeks, or netted minnows in the salt-marshes, or took to the pine-woods and the granite quarries, or chased musk-rats and hunted snapping turtles in the swamps, or mushrooms or nuts on the autumn hills, summer and country were always sensual living, while winter was always compulsory learning. Summer was the multiplicity of nature; winter was school.”

Henry Adams on growing up in and around Boston, in The Education of Henry Adams. Adams ( 1838-1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, which included his paternal grandfather, President John Quincy Adams, and great-grandfather, President (and a U.S. founding father) John Adams.

Adams’s book, published posthumously, won the 1919 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction and The Modern Library placed it first in a list of the top 100 English-language nonfiction books of the 20th Century.

As a boy he spent his summers in Quincy, just outside of Boston but large parts of which were still quite bucolic then.

Quincy Quarries Reservation, in West Quincy.

— Photo by Sswonk

'Democracy never lasts long'

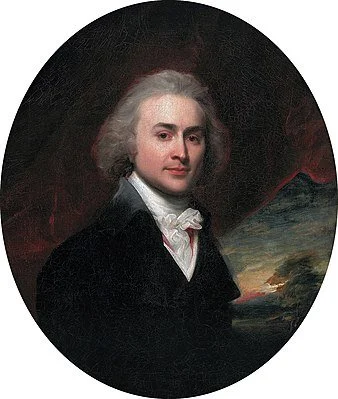

Document written by John Adams in 1776 and published anonymously.

John Adams, by Gilbert Stuart.

“I do not say that democracy has been more pernicious on the whole, and in the long run, than monarchy or aristocracy. Democracy has never been and never can be so durable as aristocracy or monarchy; but while it lasts, it is more bloody than either. … Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to say that democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious, or less avaricious than aristocracy or monarchy. It is not true, in fact, and nowhere appears in history. Those passions are the same in all men, under all forms of simple government, and when unchecked, produce the same effects of fraud, violence, and cruelty. When clear prospects are opened before vanity, pride, avarice, or ambition, for their easy gratification, it is hard for the most considerate philosophers and the most conscientious moralists to resist the temptation. Individuals have conquered themselves. Nations and large bodies of men, never.”

— John Adams (1735-1826), American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, political philosopher, writer and a U.S. Founding Father who was the second president of the United States (1797-1801) and its first vice president (1789-1797). He was a loyal native of Massachusetts. His remarks were in a letter to a Virginian, John Taylor, in 1814.

John Adams’s birthplace, in Quincy, Mass.

A temporary treatment for SAD

“Christmas Cactus, Winter Light” (oil on panel), by Yvonne Troxell Lamothe, in the show “Beyond the Curve,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Dec. 3-Jan. 16

The gallery says:

“{Ms. Lamothe} has been producing both oil paintings and watercolors mainly completed en plein air. Yvonne embraces her roots in New England. Finding intrigue with marshlands, woodlands and glorious vistas of Quincy, Mass., and Greater Boston’s South Shore, where she now lives and her cabin in Ossipee, N.H., and the White Mountains where she finds solitude gives her ample inspiration for painting. Trips to the Maine coast and Vermont offer great additional and endless places to stop and paint. It is no wonder that such a range of American painters have found their way here to New England. Among her favorites are Marsden Hartley, Lois Dodd and Milton Avery. Her paintings show close connections to the earth because of the unusual perspectives that she finds to insure a closeness to her subject. Color is of essence to Yvonne and this joy can be felt in her work. And, of course, as the earth becomes more threatened, she hopes her paintings will inspire others to take time to appreciate and celebrate our planet.’’

View of Marina Bay and Boston across Quincy Bay from Wollaston Beach, in Quincy

Center Ossipee in 1915

John O. Harney: N.E.’s changing ethnic demographics; shrinking police forces; honorary degrees and culture wars

1. Northwest Vermont 2. Northeast Kingdom 3. Central Vermont 4. Southern Vermont 5. Great North Woods Region 6. White Mountains 7. Lakes Region 8. Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region 9. Seacoast Region 10. Merrimack River Valley 11. Monadnock Region 12. North Woods 13. Maine Highlands 14. Acadia/Down East 15. Mid-Coast/Penobscot Bay 16. South Coast 17. Mountain and Lakes Region 18. Kennebec Valley 19. North Shore 20. Metro Boston 21. South Shore 22. Cape Cod and Islands 23. South Coast 24. Southeastern Massachusetts 25. Blackstone River Valley 26. Metrowest/Greater Boston 27. Central Massachusetts 28. Pioneer Valley 29. The Berkshires 30. South Country 31. East Bay and Newport 32. Quiet Corner 33. Greater Hartford 34. Central Naugatuck Valley 35. Northwest Hills 36. Southeastern Connecticut/Greater New London 37. Western Connecticut 38. Connecticut Shoreline

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Population studies. The U.S. Census Bureau released new population counts to use in “redistricting” congressional and state legislative districts. Delayed by the pandemic, the counts came close to the legal deadlines for redistricting in some states, raising concerns about whether there would be enough time for public input.

The U.S. population grew 7.4% in 2010-2020, the slowest growth since the 1930s, according to the bureau. The national growth of about 23 million people occurred entirely of people who identified as Hispanic, Asian, Black or more than one race.

The Associated Press reported:

The population under age 18 dropped from 74.2 million in 2010 to 73.1 million in 2020.

The Asian population increased by one-third over the decade, to stand at 24 million, while the Hispanic population grew by almost a quarter, to top 62 million.

White people made up their smallest-ever share of the U.S. population, dropping from 63.7% in 2010 to 57.8% in 2020. The number of non-Hispanic white people dropped to 191 million in 2020.

The number of people identifying as “two or more races” soared from 9 million in 2010 to 33.8 million in 2020, accounting for about 10% of the U.S. population.

A few New England snippets

Maine remains the nation’s oldest and whitest state, even though it saw a 64% increase in the number of Blacks from 2010 to 2020, as well as large increases in the number of Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Connecticut’s population crawled up 0.9% over the decade from 2010 to 2020 to 3,605,944 residents. The number of residents who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) increased from 29% of the population in 2010 to 37% in 2020. Connecticut’s number of congressional seats won’t change, but district borders will.

The total population of the only city on Boston’s South Shore, Quincy, Mass., topped 100,000 (at 101,636), as its Asian population grew to represent nearly 31% of all residents. Further south, the city of Brockton’s population increased by nearly 13% as the white population dropped by 29%, and the Black population increased by 26%.

Amazon jungle. Amazon last week announced it will pay full college tuition for its 750,000 U.S. hourly employees, as well as the cost of earning high school diplomas, GEDs, English as a Second Language (ESL) and other certifications. While collecting praise for its educational goodwill, stories of dire conditions in the e-commerce giant’s workplace also triggered a new California law that would ban all warehouses from imposing penalties for “time off-task” (which reportedly discouraged workers from using the bathroom) and prohibit retaliation against workers who complain.

Police shrink. Police forces in New England have recently felt new recruitment and retention pressures. In August 2021, The Providence Journal ran a piece headlined “Promises made, promises delivered? A look at reforms to New England police departments.” GoLocal reported that month that Providence policing staff levels stood at 403, down from 500 or so in the 1980s under then-Mayor David Cicilline. The number of officers employed by Maine’s city and town police departments and county sheriffs’ offices shrank by nearly 6% between 2015 and 2020, according to the Maine Criminal Justice Academy. Reporter Lia Russell of the Bangor Daily News noted, “It’s also a challenge that police in Maine are far from alone in facing, especially following a year during which police practices across the nation were called into question following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin.” The Burlington, Vt., City Council in August defeated efforts to reverse a steep cut in city police ranks. The police department currently has 75 sworn officers, down from 90 in June 2020. A survey by the police officers’ union found that roughly half of Burlington cops were actively seeking employment elsewhere.

Honor roll. Honorary degrees are becoming something of a frontline in the culture wars. Springfield College alumnus Donald Brown, who recently coauthored a piece for NEJHE, tells of his alma mater revoking the honorary master of physical education degree it had bestowed on U.S. Olympic Committee Chair Avery Brundage in 1940. In 1968, Brundage pressured the U.S. to take action against two Olympic athletes who gave the Black Power salute after finishing first and second in the 200 meters. That event was only the tip of the iceberg. Brundage had a history of anti-semitism, sexism and racism. Springfield President Mary-Beth Cooper met with the trustees and others and decided to take back the honor. Meanwhile, the University of Rhode Island has been tying itself in knots over the honorary degree it bestowed on Michael Flynn in 2014, before he was appointed Trump’s national security adviser and accused of sedition.

Refugees. After the U.S. ended its longest war (so far) in Afghanistan and the capital of Kabul fell, the question arose of where Afghan refugees would resettle. New England cities, including Worcester, Providence and New Haven, are among those that have readied plans to welcome Afghan refugees. In higher education, Goddard College President Dan Hocoy said it was a “no-brainer” to offer to house Afghan refugees at its Plainfield, Vt., campus for at least two months this upcoming fall. Back in 2004, NEJHE (then Connection) featured an interview with Roger Williams University President Roy J. Nirschel, who died in 2018, and his former wife Paula Nirschel on the university’s role in its community as well as their pioneering initiative to educate Afghan women.

Sunshine state. Before Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis took his most recent stand against fighting COVID, he displayed a narrow-mindedness that seems to always be in fashion. As Inside Higher Ed reported, after expressing concerns about faculty members “indoctrinating” students, DeSantis signed a law requiring that public institutions survey students, faculty and staff members about their viewpoint diversity and sense of intellectual freedom. The Miami Herald reported that DeSantis and state Sen. Ray Rodrigues, the original bill’s Republican sponsor, suggested that the results could inform budget cuts at some institutions. Faculty members have opposed the bill, which also allows students to record their professors teaching in order to file free speech complaints against them.

New colleges in a time of contraction. The nonprofit Norwalk (Conn.) Conservatory of the Arts announced plans to open a new performing-arts college and welcome its first class in August 2022. It’s unusual news amid the stream of college mergers and closures only widened by the pandemic. Among the challenges, many of the faculty members don’t have master of fine arts degrees that accrediting agencies require and, without accreditation, the college’s students won’t be eligible for federal financial aid or Pell Grants.

The Conservatory says the college will consolidate a traditional four-year undergraduate program into two years of intense training and a two-year graduate program into one year. Meanwhile, up the coast, the (Fall River, Mass.) Herald News reports that Denmark-based Maersk Training and Bristol Community College will work together to turn an old seafood packaging plant in New Bedford, Mass., into a National Offshore Wind Institute training facility to train offshore wind workers, complete with classrooms and a deepwater pool to train and recertify workers. (NEJHE has reported on the need to train talent for the burgeoning industry and the coastal economy’s special role in New England.)

Other higher-ed institutions are shapeshifting. After months of discussions and lawsuits, Northeastern University and Mills College reached agreement to establish Mills College at Northeastern University. Founded in 1852, Mills is renowned for its pre-eminence in women’s leadership, access, equity and social justice. Also, billionaire investor Gerald Chan and his family’s Morningside Foundation gave $175 million to the University of Massachusetts Medical School, which will be renamed the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. That’s the largest-ever gift to the UMass system.

Land deals. I was recently struck by a report titled We Need to Focus on the Damn Land: Land Grant Universities and Indigenous Nations in the Northeast. The report was born of a partnership between Smith College students and the nonprofit Farm to Institution New England (FINE) to look at how land grant universities view their historic relationships with local Indigenous tribes and how food can play a role in repairing those relationships. It grabbed my attention, partly because NEJHE has published some interesting stories about Native Americans and New England higher education. (See Native Tribal Scholars: Building an Academic Community and A Different Path Forward, both by J. Cedric Woods and The Dark Ages of Education and a New Hope, by Donna Loring.) And partly because two NEBHE Faculty Diversity Fellows, professors Tatiana M.F. Cruz of Simmons University and Kamille Gentles-Peart of Roger Williams University, are spearheading a fascinating Reparative Justice initiative. Among other things, Cruz and Gentles-Peart have had the courage to remind us that land grant universities in New England occupy the land of Indigenous communities. The Smith-FINE work offered sensible recommendations: Financially support Native and Indigenous faculty, activists, programs on campuses and beyond; offer free tuition for Native American students; hire Indigenous people, and fund their research.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Ho-Jo fried clams were addictive too

Founded in Quincy, Mass., in 1925, this was by far the most famous restaurant chain to come out of New England.

All democracies commit suicide

Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide.”

— John Adams (1735-1826), one of the most important American Founding Fathers and the second president

John Adams’s birthplace, at the Adams National Historical Park, in Quincy, Mass.

JFK speech on N.E. economic problems in 1954; region’s industries very different now!

At the now long-gone Fore River Shipyard, in Quincy, Mass., about the time of this Kennedy speech

Text of remarks by Sen. John F. Kennedy on “The Economic Problems of New England’’ June 3, 1954, in the U.S. Senate

Mr. President: Since my discussion before the Senate exactly one year ago of the economic problems of New England and their alleviation, considerable progress has been made in meeting those problems, including the organization of the twelve New England Senators in response to the call of the senior Senator from Massachusetts (Mr. Saltonstall) and myself. These 12 Senators, regardless of party, have been working faithfully on behalf of New England's needs.

But more effective action by the Executive Branch is necessary. The disappointing failures to meet many of New England's economic needs, too easily overlooked in our drive for psychological confidence, cannot be justified by recent trends. In these twelve months since my Senate speeches, unemployment in New England – which is above the national average – has increased by more than 125%* until insured unemployment has reached approximately 180,000. Manufacturing** has declined in all six New England states for a total loss of 133,000 jobs, highlighted by the 48,000 job decline in the textile industry which is now approximately 60% of its February 1951 strength. Our leather, shoe, rubber, apparel, and other non-durable goods industries have also declined; as have the more publicized machinery, metal and other durable goods industries. New England's steel fabricating mills operated in the first quarter of 1954 at 62% of capacity, 30% less than a year ago. Reports from The New England Council and the Boston Federal Reserve Bank indicate that declining defense orders will increase the difficulties of New England's electronic, aircraft, shipbuilding, and equipment manufacturers.

The battle against recession is now more nationwide in scope than it was one year ago, and it involves many legislative issues to be discussed subsequently on this floor, including taxation, credit and interest, public works, housing, farm income, and world trade, in addition to the items which I shall mention; but permit me to outline those steps which the administration should take promptly in order to help restore prosperity in New England and other similarly situated areas, and in order to complement the effectiveness of the New England members of Congress.

1. Restore bid-matching to Defense Manpower Policy No. 4, the program for channeling defense contracts to labor surplus areas. This program, both widely hailed and condemned when announced six months ago, has had only a negligible effect because of its elimination of the bid-matching features under which New England labor surplus areas had previously obtained $14 million in defense contracts. During the new policy's first full quarter of operation***, not a single contract went to a New England surplus labor area as a result of this preference, and only two "distressed areas" in the rest of the country received contracts totaling only $163,159. Moreover, only two of New England's labor surplus areas received any defense contracts at all in the first quarter; and New England's share of all defense contracts declined instead of increasing.

2. Expand the application of the administration's new policy of tax amortization certificates of necessity for industries in labor surplus areas. The delay in initiating this policy, the restrictions placed upon it, and the fact that it provided only an extra percentage for that declining number of industries already eligible for emergency amortization, have made this program of little value; and as of April 15, only two certificates under this policy had been awarded to one New England community, covering a capital investment of only $250,843. Only ten such certificates were awarded throughout the entire country. During this same period under the regular tax amortization program, the number and value of certificates of necessity awarded to all firms in all New England states continued to lag behind New England's proportionate share and defense contribution.

3. Revitalize and broaden the authority of the Small Business Administration. The establishment of this agency to strengthen the economy by aiding small business was of particular interest in New England, which has a higher proportion of small business than any other region in the United States, and where the rate of business failures is higher this year than last. But as a result of legislative ceilings and administrative delays, the Small Business Administration as of May 13 had approved in its 7½ months of operation only six loans, for a total of only $204,000 in all six New England states. Indeed, as of April 30, SBA had disbursed less than $1.2 million on thirty-seven loans throughout the nation (as compared with administrative expenses on March 30 totaling nearly $2.4 million).

4. Eliminate discrimination and confusion in New England transportation rates. I have previously pointed out examples of such discrimination and confusion in rail, truck, and ocean shipping rates, and this subject is now under review by the New England Senators Conference. ICC decisions during the past twelve months have intensified this situation. Division 2 of the Commission recently denied to New England, and its railroads and ports, the opportunity to enjoy rates on iron ore shipped by rail to the interior steel-producing areas, comparable to the rates enjoyed by the Ports of Philadelphia and Baltimore. In January, a Commission decision denied adequate service in inter-coastal shipping between the Port of Boston and the West Coast. Other recent ICC decisions affecting shipments of New England goods by truck have continued this discrimination.

5. Plug tax loopholes which contribute to improper industrial migration. The House Ways and Means Committee, in its deliberation on the tax revision bill, originally decided to plug one of the most flagrant of such loopholes by removing the immunity from "industrial development" bonds issued by states and municipalities in order to build tax-free factories as a lure to industry; but, the Committee reversed this decision and instead voted to deny the use of rentals on such factories as business deductions. The Senate Finance Committee has now voted to eliminate even this substitute, which is ineffective whenever such factories are given or cheaply sold to the migrant industry. I am hopeful that the Senate Committee or the Senate, with the administration's backing, will reinstate at least this modified version before the bill is finally passed, and eliminate this unjustifiable abuse of public credit.

6. Request legislative and administrative action to correct substandard wage competition. It is my hope that the President will reexamine his decision not to seek an increase in the minimum wage or to extend its coverage at this time; that his administration will ask Congress to modify or repeal the Fulbright Amendment to the Walsh-Healey Act which has stymied effective application of adequate nationwide minima on defense contracts; and that the Department of Justice will act more vigorously in pending litigation under the Fulbright Amendment which has delayed the adoption of realistic wage standards for the textile industry. I am particularly hopeful that this year's budget for Labor's Wage and Hour Enforcement Division will rectify last year's error, when this budget was cut 27% below the previous appropriation, thus making it possible to inspect only one out of twenty-two establishments covered by the law, requiring the complete elimination of eight southern regional offices, and making possible the review of wages in Puerto Rico only once in every seven years for each industry.

7. Initiate a program to revive the shipbuilding industry. Such a program, much discussed but not as yet forthcoming, is of particular interest in New England and other areas dependent upon this vital industry. An essential part of such a program would be to make more effective those defense manpower policies applicable to the shipbuilding industry, inasmuch as the third Forrestal-type aircraft carrier was awarded to a shipyard with increasing employment and substantial naval projects, instead of the Fore River shipyard at Quincy, Massachusetts, where employment had already dropped by more than 25%, and where seven out of its ten shipbuilding ways will be idle by this fall.

8. Support the Saltonstall-Kennedy Bill to aid research and market development in the fishing industry. The active opposition by the Department of Agriculture with the approval of the Bureau of the Budget to this measure, which seeks only to allocate to our fishing industry its fair share of tariff receipts, has handicapped its passage without restrictive amendments. I am hopeful that the administration will reverse this position, and support this bill which is of great importance to New England's hundred million dollar fishing industry.

9. Seek more effective social insurance against the ills of unemployment and forced retirement. In order to maintain community purchasing power and individual living standards, New England requires improvements in the existing Social Security Program, which improvements are only partly contained in the recommendations of the President, particularly with respect to our disabled citizens. It is especially important to strengthen our unemployment compensation program by extending coverage, providing federal reinsurance for states with low reserves and by establishing through congressional action – not, as the President asked in vain, through individual state action – minimum standards for unemployment insurance benefits and their duration. As a first step, the administration should withdraw its support, even though it is substantially modified, of the House-passed Reed Bill which would undermine the basic strength of our jobless insurance program. The bill introduced today by myself and several other Senators would far more adequately meet the needs of New England and the nation.

10. Accord equal treatment to New England and all other areas in federal programs, including those for resource development. Last year, the original budget request for the New England-New York Inter-Agency Survey of Water Resources was set at $1,200,000 in order that that survey might be completed by the end of fiscal 1954, inasmuch as its original termination was fiscal 1952. The revised budget, however, when finally enacted into law, cut this figure exactly in half, thus delaying completion by at least another year. This stepchild treatment of New England by a Federal Government which has provided direct grants for the establishment of power facilities in other areas already enjoying cheaper power rates, should be reversed by the present administration, for the recommendations of the Budget Bureau and Army Engineers are generally conclusive on such items. New England's share of the Army Civil Functions Appropriation Bill is less than that received by some two dozen individual states, practically all of whom contribute less in tax revenues than Massachusetts alone; and therefore the request for adequate funds with which to survey our potential resource development is not excessive.

It is my hope, Mr. President, that the administration will take prompt action on the 10-point program which I have outlined above, and that we in Congress – with the assistance of the twelve New England Senators who have indicated their active concern for these problems – will be able to follow through on legislation to restore economic strength and expand employment in New England and all other parts of the country.

* As measured by the average weekly insured unemployment under state programs, May 1953-May 1954.

** March 1953 to March 1954, latest available Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys.

*** Defense Department release based upon contracts of $25,000 value or more, $10,000 for Navy.

The romance of Quincy

“Peacefield,’’ the main house at the Adams National Historical Park, in Quincy, Mass., which was the Adams family homestead. The preserves the home of Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, of U.S. Ambassador to Britain Charles Francis Adams, and of writers and historians Henry Adams and Brooks Adams.

“My father and my mother have departed. The charm which has always made this house to me an abode of enchantment is dissolved; and yet my attachment to it, and to the whole region, is stronger than I ever felt before.’’

John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) in his diary entry for July 13, 1826, during his presidency. He was the sixth president; his father, John Adams, the second.

'The story of this place'

"Summer at Sailor's Home Cemetery and Black's Creek" (oil on panel), by Yvonne Troxell Lamonth, in the joint show, "Unknown Terrain,'' with Constance Bigony, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, May 1-31.

Ms. Lamonth wrote about her work:

"As the 'City' encroaches on us, pushing in and filling up any open space, a need to make reverent that which remains wild and free becomes critical. Living in Quincy, Mass., somewhat new to me, is a process of discovery. My morning walk with my dog, Wiki has becomes a small journey. Past Sailor's Pond, with its egret tree, Beechwood Knoll Elementary School and around to the Sailor's Home Cemetery path and Black's Creek the landscape comes alive.

"Color, shape, movement and constant environmental changes make capturing the essence a challenge. Working en plein air is a race against time, grabbing for the subtle changes as the channels fill and the clouds subdue the golden sea grass. Now, I am attempting to synthesize the overall experience and glory of this natural wonder. Each day I see more and gather more sensations.

"I hope to tell the story of this place. I visit and revisit certain branches and the way they fall over the field. I am surprised when pale green leaves fall over glistening snow. My awareness becomes heightened when, from my flood zone abode a short distance from the sea, I watch the waves splash over the sea wall bringing water, sand and wind closer to my comfort zone than I had ever anticipated. What comes next?

"My most recent inspirations have come from the imagination of Milton Avery, the seas and depth of Winslow Homer and the earthiness of Lois Dodd. And, of course, I look to the spirit of Marsden Hartley and Helen Torr. Learning from the greats helps inch me along.

"All this is to say, how frightened I am, not just of encroachment of 'City,' but, of our climate being undone by corporate irreverence and profit, deception and greed. How important for us all to have a voice, 'Think Globally, Act Locally.'

"Now that my neighborhood has inspired my art making, it has also become the source of my concern. I have learned about a compressor station being pushed into Weymouth, Mass., that will impact Quincy, Braintree, Boston Harbor and beyond, with toxic chemicals, causing harm to people, animals, the earth and the sea. As I make my small journey each day, I hope others will appreciate their own Mother Earth and take a stand."

'Summer was drunken'

"Peacefield,'' the former grand house of the Adamses in Quincy, Mass. It's now a museum.

Boys are wild animals, rich in the treasures of sense, but the New England boy had a wider range of emotions than boys of more equable climates. He felt his nature crudely, as it was meant. To the boy Henry Adams, summer was drunken. Among senses, smell was the strongest: smell of hot pinewoods and sweet fern in the scorching summer noon; of new-mown hay; of plowed earth; of box hedges; of peaches, lilacs, syringas; of stables, barns, cow yards; of salt water and low tide on the marshes; nothing came amiss.

Next to smell came taste, and the children knew the taste of everything they saw or touched, from pennyroyal and flag root to the shell of a pignut and the letters of a spelling book: the taste of A-B, AB, suddenly revived on the boy’s tongue sixty years afterward. Light, line, and color as sensual pleasures came later and were as crude as the rest. The New England light is glare, and the atmosphere harshens color. The boy was a full man before he ever knew what was meant by atmosphere; his idea of pleasure in light was the blaze of a New England sun. His idea of color was a peony with the dew of early morning on its petals. The intense blue of the sea, as he saw it a mile or two away, from the Quincy hills; the cumuli in a June afternoon sky; the strong reds and greens and purples of colored prints and children’s picture books, as the American colors then ran; these were ideals. The opposites or antipathies were the cold grays of November evenings and the thick, muddy thaws of Boston winter. With such standards, the Bostonian could not but develop a double nature. Life was a double thing. After a January blizzard, the boy who could look with pleasure into the violent snow glare of the cold white sunshine, with its intense light and shade, scarcely knew what was meant by tone. He could reach it only by education.

Winter and summer, then, were two hostile lives, and bred two separate natures. Winter was always the effort to live; summer was tropical license. Whether the children rolled in the grass, or waded in the brook, or swam in the salt ocean, or sailed in the bay, or fished for smelt in the creeks, or netted minnows in the salt marshes, or took to the pinewoods and the granite quarries, or chased muskrats and hunted snapping turtles in the swamps or mushrooms or nuts on the autumn hills, summer and country were always sensual living, while winter was always compulsory learning. Summer was the multiplicity of nature; winter was school.

The bearing of the two seasons on the education of Henry Adams was no fancy; it was the most decisive force he ever knew; it ran though life and made the division between its perplexing, warring, irreconcilable problems, irreducible opposites, with growing emphasis to the last year of study. From earliest childhood the boy was accustomed to feel that, for him, life was double. Winter and summer, town and country, law and liberty were hostile, and the man who pretended they were not was in his eyes a schoolmaster—that is, a man employed to tell lies to little boys. Though Quincy was but two hours’ walk from Beacon Hill, it belonged in a different world. For two hundred years, every Adams, from father to son, had lived within sight of State Street, and sometimes had lived in it, yet none had ever taken kindly to the town, or been taken kindly by it. The boy inherited his double nature. He knew as yet nothing about his great-grandfather, who had died a dozen years before his own birth; he took for granted that any great-grandfather of his must have always been good, and his enemies wicked; but he divined his great-grandfather’s character from his own. Never for a moment did he connect the two ideas of Boston and John Adams; they were separate and antagonistic; the idea of John Adams went with Quincy. He knew his grandfather John Quincy Adams only as an old man of seventy-five or eighty who was friendly and gentle with him, but except that he heard his grandfather always called “the President,” and his grandmother “the Madam,” he had no reason to suppose that his Adams grandfather differed in character from his Brooks grandfather, who was equally kind and benevolent. He liked the Adams side best, but for no other reason than that it reminded him of the country, the summer, and the absence of restraint. Yet he felt also that Quincy was in a way inferior to Boston, and that socially Boston looked down on Quincy. The reason was clear enough even to a five-year-old child. Quincy had no Boston style. Little enough style had either; a simpler manner of life and thought could hardly exist, short of cave dwelling. The flint and steel with which his grandfather Adams used to light his own fires in the early morning was still on the mantelpiece of his study. The idea of a livery or even a dress for servants, or of an evening toilette, was next to blasphemy. Bathrooms, water supplies, lighting, heating, and the whole array of domestic comforts, were unknown at Quincy. Boston had already a bathroom, a water supply, a furnace, and gas. The superiority of Boston was evident, but a child liked it no better for that.

The attachment to Quincy was not altogether sentimental or wholly sympathetic. Quincy was not a bed of thornless roses. Even there the curse of Cain set its mark. There as elsewhere a cruel universe combined to crush a child. As though three or four vigorous brothers and sisters, with the best will, were not enough to crush any child, everyone else conspired toward an education which he hated. From cradle to grave this problem of running order through chaos, direction through space, discipline through freedom, unity through multiplicity has always been, and must always be, the task of education, as it is the moral of religion, philosophy, science, art, politics, and economy; but a boy’s will is his life, and he dies when it is broken, as the colt dies in harness, taking a new nature in becoming tame. Rarely has the boy felt kindly toward his tamers. Between him and his master has always been war. Henry Adams never knew a boy of his generation to like a master, and the task of remaining on friendly terms with one’s own family, in such a relation, was never easy.

All the more singular it seemed afterward to him that his first serious contact with the President should have been a struggle of will, in which the old man almost necessarily defeated the boy, but instead of leaving, as usual in such defeats, a lifelong sting, left rather an impression of as fair treatment as could be expected from a natural enemy. The boy met seldom with such restraint. He could not have been much more than six years old at the time—seven at the utmost—and his mother had taken him to Quincy for a long stay with the President during the summer. What became of the rest of the family he quite forgot, but he distinctly remembered standing at the house door one summer morning in a passionate outburst of rebellion against going to school. Naturally his mother was the immediate victim of his rage—that is what mothers are for, and boys also—but in this case the boy had his mother at an unfair disadvantage, for she was a guest, and had no means of enforcing obedience. Henry showed a certain tactical ability by refusing to start, and he met all efforts at compulsion by successful, though too vehement protest. He was in fair way to win, and was holding his own, with sufficient energy, at the bottom of the long staircase which led up to the door of the President’s library, when the door opened, and the old man slowly came down. Putting on his hat, he took the boy’s hand without a word, and walked with him, paralyzed by awe, up the road to the town. After the first moments of consternation at this interference in a domestic dispute, the boy reflected that an old gentleman close on eighty would never trouble himself to walk near a mile on a hot summer morning over a shadeless road to take a boy to school, and that it would be strange if a lad imbued with the passion of freedom could not find a corner to dodge around somewhere before reaching the school door. Then and always, the boy insisted that this reasoning justified his apparent submission, but the old man did not stop, and the boy saw all his strategical points turned, one after another, until he found himself seated inside the school, and obviously the center of curious if not malevolent criticism. Not till then did the President release his hand and depart. .

The point was that this act, contrary to the inalienable rights of boys, and nullifying the social compact, ought to have made him dislike his grandfather for life. He could not recall that it had this effect even for a moment. With a certain maturity of mind, the child must have recognized that the President, though a tool of tyranny, had done his disreputable work with a certain intelligence. He had shown no temper, no irritation, no personal feeling, and had made no display of force. Above all, he had held his tongue. During their long walk he had said nothing; he had uttered no syllable of revolting cant about the duty of obedience and the wickedness of resistance to law; he had shown no concern in the matter; hardly even a consciousness of the boy’s existence. Probably his mind at that moment was actually troubling itself little about his grandson’s iniquities, and much about the iniquities of President Polk, but the boy could scarcely at that age feel the whole satisfaction of thinking that President Polk was to be the vicarious victim of his own sins, and he gave his grandfather credit for intelligent silence. For this forbearance he felt instinctive respect. He admitted force as a form of right; he admitted even temper, under protest, but the seeds of a moral education would at that moment have fallen on the stoniest soil in Quincy, which is, as everyone knows, the stoniest glacial and tidal drift known in any Puritan land.

From The Education of Henry Adams (an autobiography). He lived from 1838 to 1918.