Llewellyn King: A feast of knowledge at The Athenaeum

Simon Winchester in 2013

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

British bestselling author Simon Winchester last week wondered aloud whether we have too much information — so much so that it impedes our thinking.

He was speaking at The Providence Athenaeum, in Rhode Island, about his new and compelling book, Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge From Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic.

Winchester wondered whether the great minds of antiquity, who gave us what was to become Western civilization, weren’t assisted by having no legacy; weren’t boxed in by previous thinkers.

These men, including but not limited to Aristotle, Plato, Socrates, Euclid, Archimedes, Hippocrates, Thucydides and Sophocles, you might say, were the founding fathers of Western philosophy, science, history and theater.

The list is awesome and the idea of a kind of zero-sum game in thinking is intriguing. How did they do it, starting with so little knowledge in circulation around the Mediterranean about 2,500 years ago?

Winchester — who apologized for a tendency to get off the subject — mused on whether they would have been able to reach such towering intellectual heights if they had their heads stuffed full of what passes as knowledge in today’s world.

Of course, Winchester, a great purveyor of knowledge — and a lot of fun stuff — himself, doesn’t believe we should turn into know-nothings, he just raises an interesting question: How did it happen?

Winchester worked as a journalist first for the British newspapers the Guardian and then the Sunday Times. His journalism took him around the world, and from Northern Ireland’s Troubles to the numerous slums of Bangalore (now Bengaluru).

He tells in his book the story of how one woman changed the lives of otherwise hopeless children in the Bangalore slums by teaching them to read and speak in English, an official language of India. The results were that these urchins went on to great success, inside and outside of India and in many callings.

In fact, not only is Winchester’s book about learning, but it is also hugely endorsing of scholarship; he reveres libraries and during his remarks, he ran through a list of the great libraries of the world from the library of the Assyrian King Ashurbanipal to the Great Library of Alexandria to the eccentric London Library of which he is fond, less famous than the British Library.

In pondering the effects of knowledge, Winchester mentioned parenthetically how we are losing our sense of direction. This hit home for me, as my wife had a sharp sense of direction until she started using Google Maps.

In Africa, when I was a boy, the Africans could tell time with accuracy by a quick glance at the sun. This fascinated me. But when they got watches, that skill seemed to decline. Also, farmers everywhere used to determine the pH of soil by testing it on their tongues. Now they must send it to a lab.

My own favorite historical story about immaculate creation through ignorance is about James IV of Scotland, an erudite and progressive monarch. During his rule, compulsory education was introduced in 1495, and the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh was established in 1505.

James IV also had a keen interest in language and in religion. He thought that infants without parental or other influence would naturally grow up speaking Hebrew. To prove his point, he sent two infants in the care of a deaf and dumb woman to the island of Inchkeith. Some reports were that as they grew, the children could communicate with each other with grunts and their own words, but they spoke no language — let alone Hebrew.

Let me assure you that Simon Winchester, writer of books which inform (like the one about the assembling of the Oxford English Dictionary, “The Professor and the Madman,” which became a runaway success around the world) doesn’t propagate absurd theories, but they intrigue him. Ditto myself.

If you want great information, superb anecdotes and splendid writing, I suggest you read Winchester’s Knowing What We Know. You will know even more when you have read this work and your mind won’t be cluttered, just better stocked.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

On College Hill, in Providence

Providence Athenaeum interior

Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

A superb and overdue book about a great American architect

The building above is the Merchants Exchange, Philadelphia.

William Strickland (1787-1854) was one of the most important American architects. His re-interpretation of Greek temples for a modern democracy in such monuments as the Second Bank of the United States and the Merchants’ Exchange, both in Philadelphia, along with the Tennessee State Capitol, in Nashville, are among the noblest landmarks of this country’s civic identity.

William Strickland, by John Neagle, 1829, with Second Bank of the United States in the background.

-- Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery.

Although a pioneering monograph on Strickland was published in 1950, a serious study of this master has been desperately needed. Now, Robert Russell has written the definitive book, William Strickland and the Creation of an American Architecture (University of Tennessee Press).

Despite his national stature, Strickland designed only one building in New England, the Providence Athenaeum. The building committee of one of the city’s oldest cultural institutions “ascertained that William Strickland of Philadelphia had a reputation second to none in this country and in his profession” and invited the architect to Rhode Island, where he submitted a design. The library opened in the summer of 1838, having cost $18,955.76.

The Providence Athenaeum (1837-38).

Professor Russell, who wrote his dissertation at Princeton University on late medieval architecture in Italy, is one of those civilized, non-politicized historians whose interests and abilities range far beyond one narrow field. He has written a book on the buildings of Memphis and is a noted authority on gravestone restoration. His last academic post was at Salve Regina University, in Newport, where he was the director of the historic-preservation program. He is now breeding goats in the mountains of western North Carolina.

Robert Russell, in Richmond, R.I., in 2013.

Architectural histories, like that exemplified by William Strickland, set the standard in the profession before academia was sabotaged by political correctness and infected by pseudo-philosophical posturing. Russell’s writing is clear, eloquent and without the overlay of verbal obfuscation that characterizes so much contemporary writing about buildings. The sort of scholarship that characterizes the Strickland book will undoubtedly be dismissed as old-fashioned, and, since its subject led an upright life with no sex scandals or financial skullduggery, it is unlikely that the book will receive much notice. Yet the Strickland book it is the kind of treatment that so many inadequately documented American architects need, and far too few will receive in our increasingly know-nothing culture.

Architectural historian William Morgan wrote his Columbia University master’s thesis on William Strickland’s contemporary Alexander Parris, and is the author of The Almighty Wall, The Architecture of Henry Vaughan.

Back in force

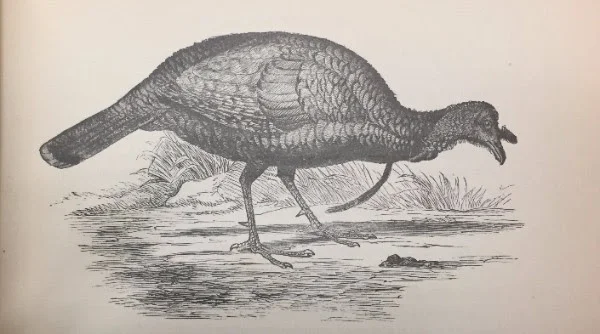

From the collection of the Providence Athenaeum: a wild turkey from A Popular Handbook of the Ornithology of the United States and Canada, by Montague Chamberlain, 1891. After many years of over-hunting, wild turkeys almost disappeared from southern New England but conservation efforts in the past few decades have brought them back big time.