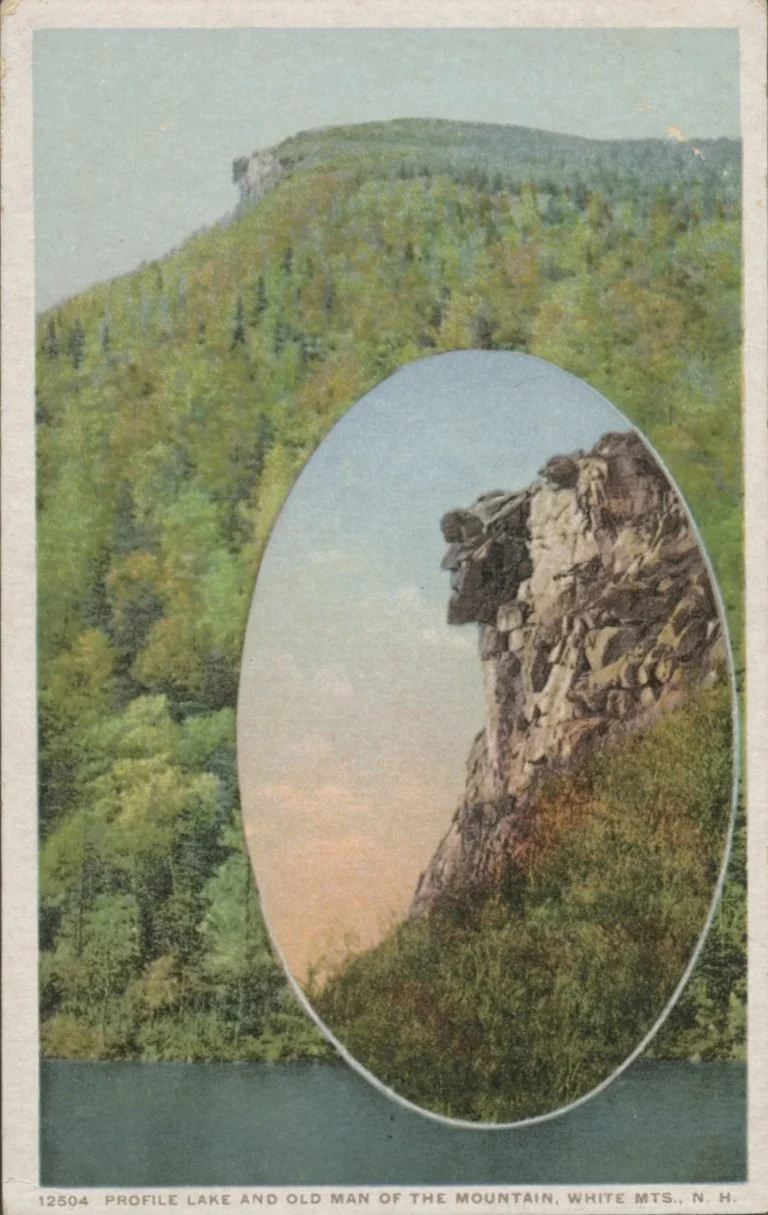

The old man in the Granite State’s heart

From the show “An Enduring Presence: The Old Man of the Mountain,’’ at the Museum of the White Mountains, at Plymouth State University, Plymouth, N.H., through Sept. 16.

The museum says:

“On May 3, 2003, New Hampshire awoke to a world in which an iconic stony face no longer looked out over Franconia Notch. For over two centuries, the Old Man of the Mountain had captured the imagination of storytellers, artists, writers, statesmen, scientists, entrepreneurs, and tourists. Twenty years later the Old Man of the Mountain remains a prominent New Hampshire icon and can still be found as an official and unofficial emblem across the state and beyond. This exhibition explores the history of the Old Man of the Mountain and the ways in which its images and narratives symbolized and reflected the evolving identity of New Hampshire and its citizens. The extraordinary story of the people and technology involved in the innovative efforts to preserve the Old Man’s place atop Cannon Mountain will also be told.’’

Robin DeRosa: An urgent call for more equity in higher education

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

PLYMOUTH, N.H.

About a year ago, I attended a meeting at the New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE) focused on reducing the cost of learning materials for college students in our region. I have been pleased since then to work with colleagues across the New England states on NEBHE’s Open Education Advisory Committee that is looking into how best to support institutions and faculty as they replace high-cost commercial textbooks with free, openly licensed resources that can make college more accessible for learners and improve student engagement and success. This work is well underway, but the world seems vastly different than it did last year, and I have been thinking about how our current reality impacts and benefits from our ongoing work in open education.

When COVID-19 shut down the college campus where I work, faculty and staff knew that many of our students would be challenged by the quick transition to emergency remote learning. Learning online can feel alien to some students, and many of our faculty had only days to transition their courses into the new modality. What may have surprised many faculty, though, was the impact that COVID-19 had on our students’ basic needs and how that impact so thoroughly halted their ability to continue their learning.

While pre-COVID surveys tell us, for example, that almost half of American college students experienced food insecurity in the month prior to being surveyed, COVID thrust many of these students from chronic precarity to immediate emergency. As work-study jobs closed, and local businesses that employed students shut down, meager incomes shriveled and affording food, housing, car payments, internet and phone service and healthcare became impossible for many.

Faculty might have worried about how students would fare with complicated content delivered over Zoom, but students were worried that they would starve, become homeless or have to witness their families fall into even more dire poverty. Students became frontline workers, increasing hours at grocery stores and gas stations even though they couldn’t afford that time away from their studies, the personal protective equipment they needed to stay safe, nor the health-care costs they’d face if they got sick. As I worked with more and more students who were trying to survive through COVID, I wondered if “open education” was really enough of an answer to this scale of crisis.

On its surface, the resurgence of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the wake of the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police officers may seem to have little to do with COVID-19. But BLM and related movements to “defund the police” are deeply entwined with critiques that highlight how systemic racism pitches the playing field against Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC).

BLM doesn’t just call out specific cases of police brutality; it asks us to look at how policing, surveillance and the justice system ironically and brutally create unfair and unsafe living conditions for some Americans. “Defunding the police” isn’t just about taking military weapons and excess funding away from departments poisoned by bad apples; it’s about reinvesting in under-resourced neighborhoods and redistributing funding for social supports in underserved areas to create healthier communities from the inside out. It’s easy to see the effects that decades of redlining and a centuries-long history of American racism have had on our students. There are thousands of data points we could examine, but stick with with food insecurity for a moment (with more stats from a recent Hope Center report): the overall rate of food insecurity among students identifying as African-American or Black is 58%, which is 19 percentage points higher than the overall rate for students identifying as white or Caucasian. When COVID ravaged our precarious students, Black students were hit especially hard. Another demographic that deals most frequently with food insecurity is students who have formerly been convicted of a crime. Think about that today, more than three months after the murder of Breonna Taylor; only her boyfriend,who was defending his home against the surprise police invasion, has been arrested in that incident.

For some students (and even contingent faculty and staff in our universities) COVID has augmented inequities that were already baked into their lives. Our continuing institutional failures to ameliorate or address these inequities can no longer be tolerated, both because the vulnerable in our colleges are at a breaking point from a global pandemic and because we have been called out by a national social justice movement that is demanding that we make real change at last. Is open education a way to answer this call?

I want to cautiously explain why I think the answer is yes. The high cost of commercial textbooks has a much larger impact on student success than most people imagine, and the benefits of switching to OER are well-documented, especially for poor students and students of color. When we imagine the reasons for these improvements in “student success,” we generally chalk it up to cost savings; after all, students can’t learn from a book they can’t afford. I don’t mean to minimize the absolutely crucial impact of cost savings on learning, but what might be even more helpful about OER is the way it asks us to rethink the kind of architecture we want to shape our education system.

Many of us are familiar with the idea of the “College Earnings Premium,” which calculates that people with college degrees on average earn much more (recently estimated at 114% more) than those who don’t have degrees. Philip Trostel, a University of Maine economist who tracks the value of public higher education, takes the story of the earnings premium much further, explaining that many market benefits extend past individuals who go to college into the community at large (for example, if more people in a region go to college, tax revenues in the region also increase and the need for public assistance goes down). Even beyond this, public benefits extend past individuals and past economics, positively affecting health, disability rates, crime rates, longevity, marital stability, happiness and more. These benefits can be passed to children (whether or not they go to college) and in some cases even to whole regions. Similarly, as OER shows such benefit to individual students, we may overlook the more public benefits of making broader policy and practical changes that would expand OER (or college access) to all students.

I don’t just want to eliminate the profit motive in the “production” and “distribution” of learning and learning materials. I also want to embed learning in a structure that is fully aware of the social, public and communal value of higher education. When a global pandemic hits, I want colleges to open their gyms as overflow hospitals, work with local food pantries to ensure access to meals for everyone in the area and develop and openly share research to aid in finding treatments and cures. This is open education. When activists raise the alarm on systemic racism in policing, I want colleges to reject plagiarism software, disarm their campus police departments, increase the number of faculty of color in their ranks, and commit resources to antiracist research and initiatives. This is open education. When we work to shift from commercial textbooks to OER, we are not just saving students money; we are centering equity in education, and we shouldn’t undersell our vision. In fact, we shouldn’t sell this vision at all.

College is not only a way to make individual students richer. OER is not only a way to save individual students money. We have a chance to rebuild a post-COVID university that sees basic needs as integral to any learner’s academic success and actively develops ways to integrate basic needs with the missions of our institutions. We have a chance to redistribute our resources away from surveillant educational technology and corporations that mine student data for profit and think more about the value of education in terms of how healthy and safe and sustainable it can make the publics outside the walls of the academy. And how the academy can be more symbiotic with those publics.

When I work on OER initiatives, especially in larger collaborations across systems and states like our NEBHE team does, I am working on a vision for the future of higher education that is deeply responsive to the inequities that are threatening the heart of our country and threatening the lives of so many Americans who are fighting for survival at the very moment I am writing this. Our colleges and universities need to step up, and open education is a framework—perhaps one of many—that can help us center equity as we go forward at a pivotal moment in time.

Robin DeRosa is the director of the Open Learning & Teaching Collaborative at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire, at the approach to the White Mountains. Check out the Museum of the White Mountains there. Hit this link:

https://www.plymouth.edu/mwm/

and:

http://digitalcollections.plymouth.edu/digital/collection/p15828coll7

Ellen Reed House, home of the English Department, at Plymouth State University

Walmart and ridgeline wind turbines in Plymouth

Photo by Atlawrence881

Lindsey Gumb: Leveraging Open Education

Source: Florida Virtual Campus (2019). 2019 Florida Virtual Campus Student Textbook & Course Materials Survey. Tallahassee, Fla.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

(Editor’s note: the author’s last name was misspelled in the headline in earlier editions; we regret the error.)

BOSTON

Late last September, I joined NEBHE as its Open Education Fellow to help build upon the grassroots efforts that have been underway for years in the Northeast aiming to lessen the burden that textbook costs place on higher education students and their families. Like so many of my colleagues doing this work day in and day out, I’m passionate about breaking down this very real barrier to student learning and success. Many people still have only a vague sense of “Open Education,” so I’d like to share some thoughts on what it is and why it matters.

I recently attended my third Open Education Global Conference in November 2019 at Politecnico di Milano in Milan, Italy. As always, I returned home from the conference, feeling inspired after engaging with colleagues from around the globe who are doing amazing things to make education more equitable and attainable for students.

The final conference keynote delivered by Cheryl-Ann Hodgkinson-Williams of the University of Cape Town in South Africa defined “open education” as an umbrella term that encompasses the products, practices and communities associated with this work. The common term that represents the products of Open Education is OER (Open Educational Resources).

OER has been defined by the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation as teaching, learning and research materials in any medium–digital or otherwise–that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions. OER include textbooks, ancillary material like quiz banks, lesson plans and syllabi, as well as full-course modules, multimedia such as video, audio and photographs, and any other intellectual property that can be protected by copyright. In short, OER can be simplified to Free + Permissions: free for the student to access and permission to partake in most if not all of the “5R” activities of reuse, revise, remix, redistribute and retain the resource at hand in perpetuity.

A learning resource may be low-cost or even free to the student, but not qualify as OER. For example, library-licensed content like e-books and scholarly journal articles are “free” for the student to access for a limited time, but those materials are still copyrighted, and in fact, are paid for by budgets supported by student tuition. This means that those resources are not actually free, and when students graduate, they lose digital access to these resources due to strict publisher agreements between the library and the publisher that stipulate only currently enrolled students be granted access. Traditional publishing is a business, after all.

Inclusive access

Another concept often conflated with OER is the “inclusive access” model. This is sweeping through our college bookstores today. Like OER, inclusive access models aim to ensure that all students have access to their learning materials on day one of class with the cost rolled into their tuition. Unlike with true OER, however, students lose access to these materials after the semester ends because of those copyright restrictions set by the publisher. Inclusive access models also strip students of their right under the “first sale doctrine” that so many took advantage of before the age of digital textbooks. This doctrine, codified at 17 U.S.C. § 109, states that an individual who knowingly purchases a legal copy of a copyrighted work (in this case, a textbook) from the copyright holder receives the right to sell it in the secondhand market. Single-semester access (like through the inclusive access model) doesn’t serve students who are taking courses in a sequence, studying for the GRE, changing careers, retaking a class or simply trying to be informed citizens throughout their lives, notes Nicole Finkbeiner, director of OpenStax at Rice University. True OER, in contrast, allow students to retain their learning content in perpetuity, serving students and learners of all ages and stages.

I often get asked: “Are the costs of textbooks really such a burden?” Yes, they are. Let’s take a closer look at the current landscape in higher ed that has educators rallying around openly licensed resources and their pedagogical benefits.

A 2018 survey of Florida’s higher education institutions showed that 64% of students aren’t purchasing the required textbook for their courses because of the high cost, 43% are taking fewer courses and 36% are earning a poor grade just because they were unable to afford the book.

A former student of mine who was a veteran was forced to wait six weeks until his stipend for books was distributed. That’s six weeks’ worth of readings, assignments, quizzes and exams for which he did not have his textbook to reference and help him prepare. Many might argue, “Just put the books on a credit card and pay it off later!” This simply isn’t an option for so many students who don’t have access to a credit card or don’t wish to take on more student debt. It’s also unrealistic for educators to determine if an assigned textbook is “affordable” or not for their students. What’s affordable for one student may be a burden for another, and it’s impossible to study from a book you can’t afford.

Academic hardships aren’t the only repercussions of expensive textbooks for our students. Many are forced to make tough decisions like skipping meals, falling behind on rent and other cost-of-living bills in order to afford their course materials. The staggering gap between state funding and tuition is putting an increasing burden on students and their families to come up with money to fund their education. While faculty have little to no control over tuition costs, they can exercise their academic freedom and elect to use OER to help alleviate the high cost of textbooks, which helps all students.

Saving students money on textbooks is critical. No student should have to decide between basic human needs like buying groceries or medications, paying rent and utility bills, going to the doctor or buying their textbooks. But we cannot pat ourselves on the back and stop at OER. My colleague on NEBHE’s Open Education Advisory Committee, Robin DeRosa at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire, put it best: “I don’t want to replace an expensive, static textbook with a free, static textbook.” She’s right. OER is not the end all be all solution, and we can’t stop there.

Not just a textbook case

Moreover, the work being done in OER extends far beyond advocating for free textbooks. Scholars and practitioners work together to continuously re-examine how to improve and build upon the existing successes, challenges and opportunities that accompany the products, practices and communities of Open Education.

Open Education has the potential to provide so many more pathways for engaged learning and innovative pedagogies, increase opportunities to intentionally build in UDL (Universal Design for Learning) practices that normalize accessibility, empower our students as content creators and contributors to the Knowledge Commons, and leverage equitable access to high-quality learning resources for all students, particularly historically marginalized groups.

Robin DeRosa and her students co-edited and published the Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature (with an open license, of course!) Students took on multiple tasks ranging from locating literature for inclusion, writing chapter introductions, and translating documents into modern English. While creating a free and openly licensed textbook for future students, DeRosa’s students also assumed the role of content creators and became published authors. The open license allows this student-created resource to be adapted and revised by other faculty and students, and interactive learning tools like Hypothes.is and H5P can be integrated into the textbook to remove that “static” element. (To view some other real examples of how educators are leveraging Open Education to encourage students take agency over their own learning experiences, I recommend checking out The Open Pedagogy Notebook, run by DeRosa and Rajiv Jhangiani, associate vice provost, open education at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in British Columbia.)

Deploying the products of Open Education, we have the potential to level the playing field and grant all students equitable access to high-quality, free postsecondary instructional materials.

Lindsey Gumb is an assistant professor and the scholarly communications librarian at Roger Williams University, in Bristol, R.I., where she has been leading OER adoption, revision and creation since 2016, focusing heavily on OER-enabled pedagogy collaborations with faculty. She co-chairs the Rhode Island Open Textbook Initiative Steering Committee. She was awarded a 2019-20 OER Research Fellowship to conduct research on undergraduate student awareness of copyright and fair use and open licensing as it pertains to their participation in OER-enabled pedagogy projects.

The funny people of Plymouth, New Hampshire

Sunset beyond the Plymouth Walmart. See the wind turbines on the ridge line.

”There's such an odd, eclectic group of people that make up the town of Plymouth, New Hampshire. I don't think I could avoid not coming out of there with a pretty good sense of humor.’’

— Eliza Coupe, actress and comedian

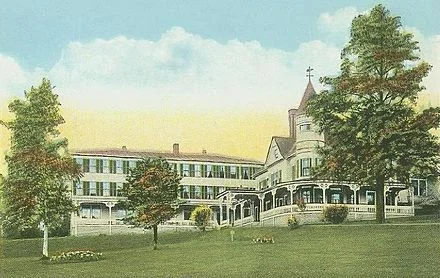

Plymouth is on the edge of the White Mountains and has long been a summer resort area, with such facilities as the late lamented Hotel Pemigewasset, whose latest version was demolished in the 1950s, to be replaced by the hideous scene at the bottom of this entry.

The hotel may be best known as being the place where famed writer Nathaniel Hawthorne died. Hawthorne had been in poor health, so in the spring of 1864 he took a trip to the White Mountains with his friend and Bowdoin College classmate, former President Franklin Pierce, to recuperate. He expired there on May 19, 1864.

Plymouth also hosts Plymouth State University and has a surprisingly large number of artists and visual artists.

Hotel Pemigewasset in 1922

Storm modeling for New England

Hurricane Bob approaching New England on Aug. 19, 1991.

From the blog of our friend Jim Brett, president of the New England Council (NEC):

"NEC member Eversource recently announced it will add Plymouth (N.H.) State University to its partnership with the University of Connecticut to improve the predictive weather modeling systems development at the Eversource Energy Center at UConn.

"Eversource will work with the two universities to develop storm modeling and damage forecasting systems designed for the New England climate. The systems will complement the Eversource Energy Center at UConn’s current power outage prediction modeling system and allow utility companies to distribute resources appropriately across the country and region in preparation to damages to an electric grid from storms.

“We are trying to improve the reliability and resilience of the entire electric grid, basically for New England. We’re trying to predict in advance what a particular weather pattern is going to do to our electric grid and the impact it will all have on our customers,” said Bill Quinlan, Eversource’s President of Operations in New Hampshire.

"The New England Council congratulates Eversource on the new collaboration that will continue to improve service to Eversource and other utility customers throughout New England.''