‘Desire and remains’

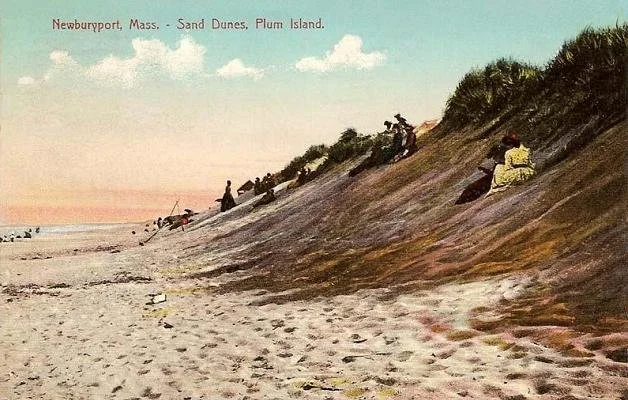

Sand dunes on Plum Island, on Massachusetts’s North Shore.

“Long waves of form, and what if under a sandhill

Socrates finds a bird? If Plato finds a lobster claw?….

And the sand — the sand is a flatbed of desire and remains.’’

— From “A Path among the Dunes,’’ by Marvin Bell (1937-2020), American poet and teacher

Lines on a beach

South Beach on Plum Island.

“What if the earth knows longing and regret,

And no one’s heard a whisper of it yet?

Why is the earth without an intimate?

These cursive lines, in which the ebbing tide

Would hint at little secrets to confide,

Denote a frilled coquette and not a bride.’’

From “On the Strand at Plum Island’’ {Mass.}, by Alfred Nicol

Lord of the North Shore

This looks like something from Brideshead Revisited. It's the Crane Estate, in Ipswich, Mass., built by plumbing-fixture mogul Richard T. Crane in the 1920s. The 59-room structure is sometimes open for tours. See: www.thetrustees.org.

It's close to the exquisite Crane Beach -- four miles of fine-grain sand backed by pitch pine forest on Ipswich Bay that's protected by a wildlife preserve. It's also close to the beautiful but often storm-battered Plum Island, named for the beach plums that flourish there. (See picture below.) But who knows if Plum Island will be there in a century, given rising seas and seemingly more frequent Nor'easters?

u\

Westport River salt marshes eroding away fast

The West Branch of the Westport River.

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

WESTPORT, Mass. — Salt-marsh islands in the West Branch of the Westport River have declined by nearly half during the past 80 years, according to a recent report.

By studying aerial imagery of six salt-marsh islands in the river’s West Branch, scientists found that the total area of salt marshes have consistently declined during the past eight decades, with losses dramatically increasing in the past 15 years. Altogether, the six islands lost a total of 12 acres of salt marsh since 1938.

Each island lost between 26 percent and 66 percent of its marsh area, according to the 16-page study conducted by the Buzzards Bay Coalition, the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program, the Marine Biological Laboratory Ecosystems Center, the Westport Fishermen’s Association and the Woods Hole Research Center.

If marsh losses continue at the accelerated rate observed during the past 15 years, the Westport River’s marsh islands could disappear within 15 to 58 years, according to the researchers.

“If you do a projection, it’s really discouraging,” said Rachel Jakuba, science director at the Buzzards Bay Coalition and the study’s coordinator. “The salt-marsh islands that are currently a characteristic feature of the Westport River could be gone in 50 years.”

Salt marshes are highly productive ecosystems that filter out pollution, provide habitat for wildlife and protect homes from flooding. More than half of commercial fish species on the East Coast use salt marshes for some part of their lives.

The study didn’t find a single cause of the accelerating loss of salt marshes, but cited nitrogen pollution and sea-level rise as two key factors. Dredging projects, erosion from large storms and grazing from crabs may also further increase losses.

Nitrogen pollution is increasingly being identified as a cause. Long-term data collected through the Baywatchers monitoring program show that the Westport River suffers from too much nitrogen pollution, with the largest source being residential septic systems. Although nitrogen pollution fuels the growth of plants, it can also cause the underground root network of salt marshes to become sparse and weak.

By examining samples of marsh plants and sediment, scientists found a relatively low ratio of underground roots and rhizomes to above-ground plant parts at all six islands. This low “roots-to-shoots” ratio suggests that all of the river’s salt-marsh islands are affected by nitrogen pollution, according to the report.

“Nitrogen concentration in the water is one factor that can contribute to marsh deterioration and loss,” said Linda Deegan, senior scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center and the Marine Biological Laboratory Ecosystems Center.

In an experiment she conducted in the Plum Island estuary in northeastern Massachusetts that began in 2003, Deegan and her colleagues found that long-term exposure to high concentrations of nitrogen in the water caused marsh plants to produce fewer roots and decomposition to increase, which led to marsh loss.

“The low roots-to-shoots ratio finding in the Westport River is very similar to our experimental results in Plum Island,” she said.

As sea-level rise accelerates, salt marshes are at risk of drowning from the rising waters. Of the six salt-marsh islands studied, the island with the lowest elevation lost the greatest number of acres since 1938, whereas the two islands with the highest elevations lost the fewest.

“The lowest elevation islands are the most vulnerable to effects of accelerating sea-level rise, but marshes on these islands also receive the most nitrogen from contact with flooding tides,” said Christopher Neill, senior scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center and former director of the Ecosystems Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory. “We strongly suspect these multiple stresses likely combine to accelerate marsh disappearance in many places.”

In addition to field work, the study analyzed at least nine aerial images of each salt-marsh island from 1938 to 2016. Using specialized mapping software, researchers determined how many acres of marsh existed in each aerial image to measure loss over time.

“We were able to ‘go back in time’ and look at changes over the decades at a level of detail that few people have,” said Joe Costa, executive director of the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program. “Over time you can see tide pools forming on top of the marsh and growing, and you can see the boundaries of salt-marsh islands receding.”

Marsh loss isn’t unique to the Westport River. Marsh loss has been observed in other rivers, harbors and coves around Buzzards Bay and along the entire East Coast. The findings in Westport could be an indicator of the future of salt marshes throughout southeastern Massachusetts.

“Global climate change, exacerbated by nitrogen pollution from local wastewater sources, is having real effects here in our backyard on Buzzards Bay,” said Mark Rasmussen, president of the Buzzards Bay Coalition.