Philip K. Howard: Reframing Andrew Yang’s ideas for a new political party

Andrew Yang

Every so often, a citizen emerges to challenge the political establishment. Ross Perot’s 1992 presidential run drew on a public hunger for a new approach; he received 20 percent of the vote. In 2016 Donald Trump steamrolled traditional Republican candidates and changed the party’s face to his own. Andrew Yang is more a firecracker than a depth charge, but he has captured the public imagination with his refreshing candor and fearlessness.

Unlike Perot or Trump, Yang came from nowhere—no public reputation, no big money, no access to any part of the establishment. Yet, by force of his personality, Yang now has a pedestal in the political landscape. In his new book, Forward: Notes on the Future of Our Democracy, Yang plants the flag of a new political party. He argues that, though Americans are not as polarized as polls suggest, neither existing party will address the legitimate needs of the other side. He also says that the two parties are comfortable with their duopoly of failure—first you fail, then I fail—and therefore will not support disruptive electoral reforms such as ranked-choice voting.

Yang is not the first to suggest that our two political parties no longer represent most Americans. Frank DiStefano, in his recent essay in these pages, argued that the parties are on “a locked-in path to destruction and decline.” In my 2019 book, Try Common Sense, which Yang cites, I said that each party’s outmoded ideology precludes the overhauls needed to respond to public frustration.

It is no surprise that a plurality of voters now identifies as “independent” or as a member of a third party. But the electoral machinery makes it difficult for a would-be candidate to operate outside the two parties; and the primary system promotes extremists, not problem solvers.

Yang’s idea of a party is, initially, not one with its own candidates but a centrist movement that exercises influence on candidates from both parties. As DiStefano elaborates it, a movement that captures public imagination can eventually take over or supplant one of the parties. The challenge is to galvanize public support for this type of new overhaul movement in a political environment like today’s, which breeds deadlock, not solutions. While many Americans might be receptive to a new party, the current political shouting match has left them exhausted and cynical. There is a huge gulf today between wanting change and rolling up your sleeves to force change.

So, what does it take to engender the excitement needed for a new movement? Yang proposes a six-point platform for his Forward Party:

1. Ranked-choice voting, with open primaries: These arrangements would reduce the stranglehold of the two parties and defang the extremists.

2. Fact-based governing: The idea here is to evaluate programs objectively.

3. Human-centered capitalism: Yang wants to re-center business around employees and communities, not just owners.

4. Effective and modern government: Here Yang embraces the need to “fix the plumbing” of paralyzed government.

5. Universal Basic Income: Giving Americans $1,000 per month was Yang’s signature proposal in his presidential campaign—a proposal that was validated, he argues, by the Covid relief payments.

6. Grace and tolerance: Yang urges Americans to be more accepting of each other, not stay locked in a battle of identity politics.

By opening the door to a new party, Yang once again reveals solid leadership instincts. But a new movement requires a tougher, more focused platform. A list of centrist do-good reforms is unlikely to elicit the public passion needed to dislodge the current parties. Yang himself is a bold and disarming figure; his party must be as well. A new party needs a clarion call that can galvanize popular support—as the Progressive Movement did, for example, with its vision of public oversight of food and fair practices, or the New Deal with its idea of social safety nets. Successful movements also energize public passion by fingering villains, as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street did.

To get Americans out of their easy chairs, the new party must light a bonfire. Yet Yang’s platform is soporific, with no inspirational theme or evil targets. What’s the vision? Who are the enemies? Here is the way I would reframe Yang’s proposed Forward Party.

First, the clarion call for a new way of governing: Responsibility for America. Americans have lost their sense of self-determination. We should be re-empowered to make a difference. Revive individual responsibility at all levels of society. Replace mindless bureaucracy with accountability for results. Teachers should be free to do their best, with authority to maintain classroom discipline. Principals should be free to hold teachers accountable, and the same should hold true all the way up the chain of responsibility. Officials must be free to authorize action within a reasonable timeframe; and they, too, must be accountable up the chain of responsibility. Mayors and police chiefs should have authority to manage the police force and other departments, including authority to promote public employees who do their jobs and fire those who don’t.

Reviving human responsibility requires overhauling government’s operating systems, replacing thick rule books with simpler goals and principles managed by people who take responsibility for themselves and are accountable to others. This is not so hard: It is far easier to agree on goals than to bicker over endless details of implementation. Modern American government has become basically a bad form of central planning, tying Americans into knots of red tape. Ask any teacher or doctor. Restoring responsibility would empower officials and citizens to govern better and adapt to local needs.

Second, identify enemies and attack them. Powerful forces will resist a movement to revive responsibility. I see two main villains: public unions, which exist to block all accountability, and the political parties themselves, which have become organs of identity politics and special interests. It is impossible to fix broken government or revive a shared sense of national purpose without defeating these villains.

Public unions have made government unmanageable and must be outlawed. Public unions have preempted democratic governance. Citizens elect leaders to run the police force and schools, but these leaders have no authority to fulfill this responsibility. The Minneapolis mayor appointed the police chief; but under the police union’s collective-bargaining agreement, the mayor lacked authority to fire the rogue cop who killed George Floyd—or even to reassign the officer. Unlike private unions, which are dependent on the success of a private enterprise, public unions retain power even where they cause government to fail miserably.

Democracy is supposed to be a process of giving officials responsibility and holding them accountable. But public unions have broken the links: Today, there is zero accountability in the daily operations of American government. Without accountability, rote compliance with the thick rule books replaces individual responsibility for results. The bottom line today is a government bogged down in a bureaucratic jungle of dictates and entitlements. Nothing much works sensibly or fairly because no one is empowered to make things work.

As for political parties, they compete through failure, not achievement. Party leaders have basically given up on reforming government. Instead, they take turns in power pointing to the failures of the incumbent. In 2016 presidential candidate Donald Trump tapped into broad public frustrations with Washington. Trump’s erratic leadership opened a door through which Joe Biden entered, offering sanity. But Biden’s failures of execution in Afghanistan and on the Mexican border now empower Republicans to go on the attack and prepare for their own return.

This spiral of negative democratic competition is accelerated by the rise of extremism: Each side stokes fear of the extremists on the other (“Defund the police!” “Stop the steal!”). Actually fixing government is no longer the way the parties compete.

Each party will aggressively resist reforms that would revive responsibility. Public unions have a stranglehold on the Democratic Party. Identity groups on the left will resist any accommodation of other points of view, or what Andrew Yang calls “grace and tolerance.” Republicans have become a party of nihilism and offer no discernible governing vision. They will rail against any reform that empowers public officials, opens elections to moderate candidates, or imposes taxes for public projects.

The existing political parties are the problem, not the path to a solution. The new party envisioned by Yang must ultimately supplant one of them. The new party must ask its supporters to defeat the defenders of the status quo: They are not the agents but the enemies of a successful future. Generating public enthusiasm will require not a laundry basket of reforms but a spear with a sharp point. No matter which party is in charge, focus on its virtually unblemished recent record of failure.

America needs a new party. Its vision must be condensed into a new governing principle that resonates with American values and represents a clean break from bureaucratic paralysis—a principle like human responsibility, which can guide an overhaul of all levels of government.

The current state of American politics has squeezed all energy and hope out of our democracy. There’s no oxygen to serve as fuel for anyone who wants to do what is needed. Yang has cracked open a door, but we need a new vision to open it wide and attract a public enervated by decades of failure.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, author, civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder of the government- and legal-reform nonprofit organization Common Good (commongood.org) and author, most recently, of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left (2019). This essay first appeared in American Purpose.

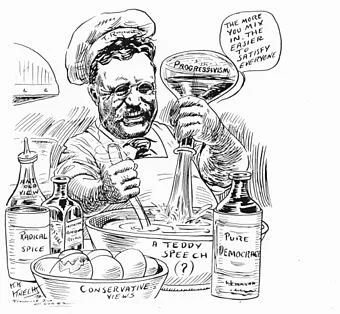

Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party’s (aka “Bull Moose Party’’) presidential candidate in 1912, mixing ideologies in his speeches in this 1912 editorial cartoon by Karl K. Knecht (1883–1972) in the Evansville (Ind.) Courier. The former president’s running mate was California Gov. Hiram Johnson.

Philip K. Howard: The administrative state is paralyzing American society

VERNON, Conn.

Philip K. Howard’s powers of concision are remarkable. In a very readable Yale Law Journal piece, “From Progressivism to Paralysis,” Howard, founder of the nonprofit and nonpartisan reform group Common Good (commongood.org), writes:

"The Progressive Movement succeeded in replacing laissez-faire with public oversight of safety and markets. But its vision of neutral administration, in which officials in lab coats mechanically applied law, never reflected the realities and political tradeoffs in most public choices. The crisis of public trust in the 1960s spawned a radical transformation of government operating systems to finally achieve a neutral public administration, without official bias or error. Laws and regulations would not only set public goals but also dictate precisely how to implement them. The constitutional protections of due process were expanded to allow disappointed citizens, employees, and students to challenge official decisions, even managerial choices, and put officials to the proof. The result, after fifty years, is public paralysis. In an effort to avoid bad public choices, the operating system precludes good public choices. It must be rebuilt to honor human agency and reinvigorate democratic choices.”

The gravamen of the article is that progressive precisionism causes paralysis because laws and regulations must be general and non-specific enough to allow administrative creativity. And, a correlative point, administrators should not be permitted to arrogate to themselves legislative or judicial functions that belong constitutionally to elected representatives.

Why not? Because in doing so the underlying sub-structure of democratic governance is subtly, and sometimes not so subtly, fatally undermined. The authority of governors rests uneasily upon the ability of the governed to vote administrators and representatives in and out of office, a necessary democratic safeguard that is subverted by a permanent, unelected administrative state that, like a meandering stream, has wandered unimpeded over its definitional banks.

Detecting a beneficial change in the fetid political air, Howard warns, “Change is in the air. Americans are starting to take to the streets. But the unquestioned assumption of protesters is that someone is actually in charge and refusing to pull the right levers. While there are certainly forces opposing change, it is more accurate to say that our system of government is organized to prevent fixing anything. At every level of responsibility, from the schoolhouse to the White House, public officials are disempowered from making sensible choices by a bureaucratic and legal apparatus that is beyond their control.”

And then he unleashes this thunderbolt:

“The modern bureaucratic state, too, aims to be protective. But it does this by reaching into the field of freedom and dictating how to do things correctly. Instead of protecting an open field of freedom, modern law replaces freedom.

“The logic is to protect against human fallibility. But the effect, as discussed, is a version of central planning. People no longer have the ability to draw on ‘the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place,’ which Nobel economics laureate Friedrich Hayek thought was essential for most human accomplishment. Instead of getting the job done, people focus on compliance with the rules.

“At this point, the complexity of the bureaucratic state far exceeds the human capacity to deal with it. Cognitive scientists have found that an effect of extensive bureaucracy is to overload the conscious brain so that people can no longer draw on their instincts and experience. The modern bureaucratic state not only fails to meet its goals sensibly, but also makes people fail in their own endeavors. That is why it engenders alienation and anger, by removing an individual’s sense of control of daily choices.”

Indeed, as a lawyer (sorry to bring the matter up), Howard probably knows at first hand that complexity, which provides jobs aplenty for lawyers and accountants, is the enemy of creative governance. The way to a just ordered liberty is not by mindlessly following ever more confusing and complex rules – written mostly by those who intend to preserve an iron-fisted status quo – but by leaving open a wide door of liberty in society for those who are best able to provide workable solutions to social and political problems.

Howard, I am told by those who know him well, is not a “conservative’’ in terms of the current American political parlance. For that matter, besieged conservative faculty at highbrow institutions such as Yale are simply exceptions that prove the progressive rule; such has been the case before and since the publication of Yalie William F. Buckley Jr.’s book, God and Man at Yale.

But I am also assured that Howard is an honest and brave man.

In an era in which democracy is being throttled by a weedy and complex series of paralytic regulations produced by the administrative state, any man or woman who can write this – “It is better to take the risk of occasional injustice from passion and prejudice, which no law or regulation can control, than to seal up incompetency, negligence, insubordination, insolence, and every other mischief in the service, by requiring a virtual trial at law before an unfit or incapable clerk can be removed” -- is worth his or her weight in diamonds.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Philip K. Howard: Misdiagnosing what has led to failed state America

People want answers for what went wrong with America’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic—from lack of preparedness, to delays in containing the virus, to failing to ramp up testing capacity and the production of protective gear. But almost nowhere in the current discussion can one find a coherent vision for how to avoid the same problems next time or help restore a healthy democracy.

Bad leadership has been identified as a primary culprit. The “fish rots from the head,” as conservative columnist Matthew Purple puts it. There’s plenty to blame President Trump for, but stopping there, as, say, former New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani does, ignores many bureaucratic failures. Cass Sunstein gets closer to the mark by focusing on how red tape impedes timely choices, but even he sees the bureaucratic structures as fundamentally sound and simply in need of some culling. Sunstein suggests that “it might be acceptable or sensible to tolerate a delay” in normal times, but not in a pandemic. Tech investor Marc Andreessen sees a lack of national willpower, an unwillingness to grab hold of problems and build anew. Prominent observers such as Francis Fukuyama, George Packer and Ezra Klein blame a broken political system and a divided culture; they offer little hope for redemption, even with new leadership.

All misdiagnose what caused government to fail here, and they confuse causes with what are more likely symptoms. Fukuyama rightly identifies a critical void in American political culture: the loss of a high “degree of trust that citizens have in their government,” which countries such as Germany and South Korea enjoy. But why have Americans lost trust in their government?

No doubt, after this is all over, a report will catalog the errors and misjudgments that let COVID-19 shut down America. The report will likely begin years back, when officials refused to heed warnings about pandemic planning. It will further expose President Trump, who for almost two months said that the coronavirus was “totally under control.” Errors of judgment like these are inevitable, to some degree—they happened before and after Pearl Harbor and 9/11, too—and with luck, they will inform future planning. The light will then shine on the operating framework of modern government, revealing not mainly errors of judgment, or cultural divisions, but a tangle of red tape that causes failure. At every step, officials and public-health professionals were prevented from making vital choices by legal obstacles.

Andreessen is correct that Americans have lost the spirit to build, but that’s because we’re not allowed to build. A governing structure that takes upward of a decade to approve an infrastructure project and ranks 55th in World Bank assessments for “ease of starting a business” does not encourage individual and institutional initiative. Of course Americans don’t trust government—it gets in the way of their daily choices, even as it fails to meet many national needs.

Our response to the COVID-19 missteps should not be to wring our hands about our miserable political system, or about the cynicism and selfishness that have infected our culture. We should focus on why government fails in making daily choices. What many Americans see clearly—but most public intellectuals cannot see—is a system that prevents people from acting on their best judgment. By re-empowering officials to do what they think is right, we may also reinvigorate American culture and democracy.

The root cause of failed government is structural paralysis. What’s surprising about the tragic mishaps in dealing with COVID-19 is how unsurprising they were to the teachers, nurses and local officials who are continually stymied by bureaucratic rules. A few years ago, a tree fell into a creek in Franklin Township, N.J., and caused flooding. A town official sent a backhoe to pull it out. But then someone, probably the town lawyer, pointed out that a permit was required to remove a natural object from a “Class C-1 Creek.” It took the town almost two weeks and $12,000 in legal fees to remove the tree.

In January, University of Washington epidemiologists were hot on the trail of COVID-19. Virologist Alex Greninger had begun developing a test soon after Chinese officials published the viral genome. But while the coronavirus was in a hurry, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was not. Greninger spent 100 hours filling out an application for an FDA “emergency-use authorization” (EUA) to deploy his test in-house. He submitted the application by e-mail. Then he was told that the application was not complete until he mailed a hard copy to the FDA Document Control Center.

After a few more days, FDA officials told Greninger that they would not approve his EUA until he verified that his test did not cross-react with other viruses in his lab, and until he agreed also to test for MERS and SARS. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) then refused to release samples of SARS to Greninger because it’s too virulent. Greninger finally got samples of other viruses that satisfied the FDA. By the time they arrived, and his tests began, in early March, the outbreak was well on its way.

Regulatory tripwires continually hampered those dealing with the spreading virus. Hospitals learned that they couldn’t cope except by tossing out the rulebooks; other institutions weren’t so lucky. For example, after schools were shut down, needy students no longer had meals. Katie Wilson, executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance and a former Obama administration official, secured an agreement in principle to transfer federal meal funding to a program that provides meals during summer months. But red tape required a formal waiver from each state, which in turn required formal waivers from Washington. The bureaucratic instinct was relentless: school districts in Oregon were first required to “develop a plan as to how they are going to target the most-needy students.” Meantime, the children got no meals. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens, interviewing Wilson, summarized her plea to government: “Stop getting in the way.”

What’s needed to pull the tree out of the creek is no different than what’s needed to feed school kids: responsible people with the authority to act. They can be accountable for what they do and how well they do it, but they can’t succeed if they must continually pass through the eye of the bureaucratic needle.

Reformers are looking in the wrong direction. Electing new leaders won’t liberate Americans to take initiative. Nor is “deregulation” generally the solution for inept government; the free market won’t protect us against pandemics. The only solution is to replace the current operating system with a framework that empowers people again to take responsibility. We must reregulate, not deregulate.

American government rebuilt itself after the 1960s on the premise of avoiding human error by replacing human choice. That’s when we got the innovation of thousand-page rulebooks dictating the one-correct-way to do things. We mandated legal hearings for ordinary supervisory choices, such as maintaining order in classrooms or evaluating employees. We replaced human judgment with rules and objective proof. Finally, government would be pure—almost like a software program. Just follow the rules.

For 50 years, legislative and administrative law has piled up, causing public paralysis and private frustration. Almost no one has questioned why government prevents people from using their common sense. Conservatives misdiagnose the flaw as too much government; liberals resist any critique of public programs, assuming that any reform is a pretext for deregulation. In the recent Democratic presidential debates, no one asked how to make government work better.

Experts have it backward. Polarized politics, they say, causes public paralysis. While hyper-partisanship certainly paralyzes legislative activity, the bureaucratic idiocies that delayed everything from COVID-19 testing to school meals had nothing to do with politics. Paralysis of the public sector came first, leading to polarized politics.

By the 1990s, broad public frustration with suffocating government fueled the rise of Newt Gingrich. The growth of red tape made it hard to make anything work sensibly. Schools became anarchic; health-care bureaucracy caused costs to skyrocket; getting a permit could require a decade; and Big Brother was always hovering. Is your paperwork in order? Americans kept electing people who promised to fix it—the “Contract with America,” “Change we can believe in,” and “Drain the swamp”—but government was beyond the control of those elected to lead it. What happens when politicians give up on fixing things? They compete by pointing fingers—“It’s your fault!”—and resort to Manichean theories and identity-based villains. Public disempowerment breeds extremism.

A functioning democracy requires the bureaucratic machine to return to officials and citizens the authority needed to do their jobs. That necessitates a governing framework of goals and principles that re-empowers Americans to take responsibility for results. Giving officials, judges, and others the authority to act in accord with reasonable norms is what liberates everyone else to act sensibly. Students won’t learn unless the teacher maintains order in the classroom. New ideas by a teacher or parent go nowhere if the principal lacks the authority to act on them. To get a permit in timely fashion, the permitting official must have authority to decide how much review is needed. To enforce codes of civil discourse—and not allow a small group of students to bully everyone else—university administrators must have authority to sanction students who refuse to abide by the codes. To prevent judicial claims from becoming weapons of extortion, judges must have authority to determine their reasonableness. To contain a virulent virus, public-health officials must have authority to respond quickly.

Giving officials the needed authority does not require trust of any particular person. What’s needed is to trust the overall system and its hierarchy of accountability—as, for example, most Americans trust the protections and lines of accountability provided by the Constitution. There’s no detailed rule or objective proof that determines what represents an “unreasonable search and seizure” or “freedom of speech.” Those protections are nonetheless reliably applied by judges who, looking to guiding principles and precedent, make a ruling in each disputed situation.

The post-1960s bureaucratic state is built on flawed assumptions about human accomplishment. There is no “correct” way of meeting goals that can be dictated in advance. Nor can good judgment be proved by some objective standard or metric. Judgments can readily be second-guessed, as appellate courts review lower-court decisions, but the rightness of action almost always involves perception and values. That’s the best we can do.

The failure of modern government is not merely a matter of degree—of “too much red tape.” Its failure is inherent in the premise of trying to create an automatic framework that is superior to human choice and judgment. We thought that we could input the facts and, as Czech playwright and statesman Vaclav Havel once parodied it, “a computer . . . will spit out a universal solution.” Trying to reprogram this massive, incoherent system is like putting new software onto a melted circuit board. Each new situation will layer new rules onto ones already short-circuiting.

Nothing much will work sensibly until we replace tangles of red tape with simpler, goal-oriented frameworks activated by human beings. This is a key lesson of the COVID-19 crisis. It’s time to reboot our governing system to let Americans take responsibility again.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, civic leader and photographer, is founder of Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left. This piece first ran in City Journal.

Philip K. Howard: A plan to fix America's crumbling infrastructure?

The Crook Point {Railroad} Bridge over the Seekonk River, in Rhode Island.

Fixing America’s decrepit infrastructure enjoys rare bipartisan support. But the recent announcement of a $2 trillion plan by President Trump, Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) was quickly doused by reality. White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney said the proposal would go nowhere without permitting reform. Leaders in Congress, including some Democrats, said they would not support any significant increase in gasoline taxes to fund it.

No one seriously doubts the need to modernize America’s infrastructure. The main stumbling block is broad distrust of Washington’s ability to deliver any large public works initiative. Getting past this impasse offers a unique opportunity to reboot the rules, cutting effective costs by over 50 percent. Here are three reforms that should be enacted as the foundation of any infrastructure bill:

Permitting reform: In 2009, Congress authorized $800 billion to stimulate the economy, promising to rebuild infrastructure. In the final tally, a grand total of 3.6 percent was spent on transportation infrastructure. Projects never got out of the gate, because, as President Obama put it, “There’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects.”

The red tape is also cripplingly expensive. The 2015 Common Good report, “Two Years, Not Ten Years,” found that a six-year delay in permitting more than doubles the effective cost of projects, and lengthy environmental reviews are generally harmful to the environment because they prolong polluting bottlenecks.

The reform needed is not to weaken environmental rules but to create clear lines of authority to make the decisions needed to adhere to deadlines. For example, a project with minimal environmental impact — such as raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge using existing foundations — does not need a 10,000-page analysis (plus another 10,000 pages of appendices). Common Good has a three-page legislative proposal that gives designated officials the job of deciding the proper scope of environmental review and resolving disagreements among different agencies.

Discipline in prioritizing and procuring projects: Cynics don’t have to look far to see the likelihood of wasting public funds on pork such as “the bridge to nowhere.” Just as most of the 2009 stimulus was distributed to states in block grants, so too it is likely that much of any large infrastructure initiative will end up being distributed for political purposes.

Nor should the price tag of infrastructure be inflated to meet unrelated social goals. The goal is modern roads, locks and electrical grids — not, as Pelosi and Schumer stated, an “imperative to involve women, veteran and minority-owned businesses.”

Congress should create an independent National Infrastructure Board, using the model of base-closing commissions, to set priorities for use of public infrastructure funds. That’s how Australia does it — it receives applications from states and then announces who gets federal funds.

A National Infrastructure Board could avoid pork barrel projects and avoid use of critical infrastructure as pawns in unrelated political disputes. The Trump administration early on highlighted the new Gateway rail tunnel into Manhattan as a critical need of the Northeast. This $30 billion project is vital not only for commuters and rail travelers, but also for vehicular traffic. Gridlock would extend for 25 miles if one of the two existing rail tunnels shuts down long term. Now that project is being held up because President Trump is using it as a political chip in a running dispute with Senators Schumer and Cory Booker (D-N.J.).

The National Infrastructure Board also could oversee contracting policies, to avoid waste of inflexible procurement practices and local featherbedding.

Funding infrastructure: User fees will only repay a small portion of the cost of most public infrastructure. Republicans are correct that Washington is filled with wasteful programs that can be cut. Democrats (supported by the Chamber of Commerce and Business Roundtable) are correct that gas taxes, last set in 1993, have not kept up with inflation. The obvious political compromise is for Congress to use both sources and create a funding plan that is half cuts and half new taxes. A 25-cent hike in gas taxes would raise about $40 billion each year. The 2010 Simpson-Bowles debt reduction plan offers a road map for cutting obsolete subsidies, such as New Deal farm subsidies.

Modernizing America’s infrastructure would be a boon to the economy — enhancing competitiveness and creating over a million jobs that cannot go offshore. It would result in a greener footprint. The case for funding is compelling if accompanied by streamlined permitting and a National Infrastructure Board to avoid waste. Abandoning the legacy bureaucracies that stifle infrastructure projects might be the most important change of all — rebooting the rules could demonstrate what’s needed to fix broken government.

Philip K. Howard is chairman of Common Good and author of the new book Try Common Sense. This piece first ran in The Hill.

Follow him on Twitter@PhilipKHoward.

Philip K. Howard: A radical centrist platform for 2020 --replace red tape with individual responsibility

Centrist politics don’t offer the passion of absolutist solutions. In the words of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.): “Moderate is not a stance. It’s just an attitude towards life of, like, ‘meh.’”

But electoral success in 2020 likely will hinge on who attracts the centrist voters. One issue seems to unite most Americans: Frustration with how government works. Political scientist Paul Light recently found 63 percent of voters support “very major reform” of federal government, up from 37 percent 20 years ago.

For several decades, Americans have elected “outsider” candidates who promise some version of Barack Obama’s “change we can believe in.” Yet nothing much changes. The elections of Obama and Donald Trump can be viewed as symptoms of unrequited reform. When Obama’s promise of change got bogged down, 8 million Obama voters turned around and voted for Trump. Now Trump’s promise to “drain the swamp” is headed towards futility, amounting to little more than reversing Obama-era executive orders.

What’s missing is a governing vision that makes Americans part of the solution. Only then can leaders attract the popular mandate needed to overcome the resistance of Washington. Only then will there be a principled basis for officials and citizens to make practical choices going forward.

The best model for modern government is to revive the framework of democratic responsibility designed by the Framers: Replace red tape with human responsibility at all levels of society. This governing vision, though centrist, requires a radical simplification of Washington bureaucracies.

Over the past 50 years, almost without anyone noticing as it happened, the jungle of red tape in Washington has grown progressively denser — at this point 150 million words of detailed statutes and regulations (over 180,000 pages of the Code of Federal Regulations and over 40,000 pages of the U.S. Code). The effects of this build-up include bureaucratic paralysis and pervasive micromanagement of daily choices throughout society.

Bureaucracy is staggeringly costly. Common Good’s 2015 report, “Two Years, Not Ten Years,” found that a six-year delay in permitting infrastructure more than doubles the effective cost of projects. Twenty states now have more non-instructional personnel than teachers in their schools, mainly to comply with legal reporting requirements. The administrative costs of American health care are estimated to be as much as 30 percent — that’s about $1 trillion, or $1 million per physician.

Bureaucracy is a prime source of voter alienation. Many Americans today don’t feel free to be themselves — almost any decision, comment, joke, or child’s play activity can involve legal risk. Rule books tell us how to correctly run schools and provide social services. Small businesses are put in an almost impossible position of being regulated by multiple agencies with detailed requirements — a family-owned apple orchard in New York state, for example, is regulated by about 5,000 rules from 17 different regulatory programs. Fear of offending employees leads many companies to impose speech codes that, studies suggest, exacerbate discriminatory feelings.

Since Ronald Reagan’s tenure in the White House, the Republican mantra has been deregulation. Yet what frustrates most Americans is not public goals, such as safeguarding against unsafe work conditions, but micromanaging exactly how to organize a safe workplace with thousands of detailed rules. One-size-fits-all regulations often drive Americans to resistance, because rigid rules don’t honor tradeoffs, local circumstances, or a sense of proportion in enforcement.

This reform vision is simple: Focus regulation on goals and guidelines. Simpler codes will allow Americans to understand what is expected of them and will afford them flexibility to get there in their own ways. The reform is also radical: Legacy bureaucracies must be largely replaced with these simpler codes. Detailed rules would be limited to areas such as effluent limits where specificity is essential. The resulting regulatory overhaul would be historic, comparable in magnitude to the Progressive Era.

Area by area, recodification commissions would propose to Congress new codes. Public goals that require practical choices, such as overseeing safe and adequate services, would allow flexibility and local innovation. Instead of Big Brother breathing down our necks, Washington would be more like a distant uncle, intervening only when citizens or local officials transcended boundaries of reasonableness.

Not that long ago, that’s how government was organized. The Interstate Highway Act in 1956 was 29 pages long. Ten years later, over 20,000 miles of highway had been built. By contrast, the most recent highway bill was almost 500 pages long, and implemented by thousands of pages of regulations.

Law is more effective when people focus on goals. The Constitution is only 15 pages long, but its principles nonetheless are effective to protect our freedoms. Agencies where officials take responsibility for ultimate goals, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with its focus on disease reduction, accomplish more than those such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which is organized around rote compliance with thousands of rules.

No one designed the current bureaucratic tangle. It just grew and grew more, as each ambiguity sprouted a new rule. Leaders can’t lead it, because the rules trump common sense. But that’s precisely why a new movement is needed. Legacy bureaucracies never fix themselves.

Philip K. Howard is chair of Common Good and author of the new book Try Common Sense (W.W. Norton, 2019). Follow him on Twitter@PhilipKHoward.

TAGS ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ DONALD TRUMP BARACK OBAMA POLITICS OF THE UNITED STATES DEMOCRATIC PARTY REPUBLICAN PARTY 2020 CAMPAIGN FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

Philip K. Howard: Red tape has replaced responsibility

For decades now, Americans have slogged through a rising tide of idiocies. Getting a permit to do something useful, say, open a restaurant or fix a bridge, can take years. Small businesses get nicked for noncompliance of rules they didn’t know. Teachers are told not to put an arm around a crying child. Doctors and nurses spend up to half the day filling out forms that no one reads. Employers no longer give job references. And, in the land of the First Amendment, political incorrectness can get you fired.

We’d all be better off without these daily frustrations. So why can’t we use our common sense and start fixing things?

But common sense is illegal in Washington. Red tape has replaced responsibility. No official has authority even to do what’s obvious. In 2009, Congress allocated $800 billion, in part to rebuild America’s infrastructure. But it didn’t happen because, as President Obama put it, there’s “no such thing as a shovel-ready project.” Even President Trump, a builder, can’t get infrastructure going. The entire government was shut down in a spat over one project, the Mexican border wall, that the parties don’t agree on. How about fixing the broke rail tunnel coming into New York?

Washington’s ineptitude is only the tip of the iceberg. A bureaucratic mindset has infected American culture. Instead of feeling free to do what we think is right, Americans go through the day looking over our shoulders: “Can I prove that what I’m about to do is legally correct?”

Every Republican administration since Reagan has promised to cut red tape with deregulation. “Washington is not the solution,” as Reagan put it: “It’s the problem.” But Washington has only gotten bigger during their terms in office. That’s because deregulation is too blunt: Americans want Medicare, clean water, and toys without lead paint.

Americans are not stupid. Government drives people nuts because it prevents anyone from being practical. Nothing’s wrong with requiring a permit for a new restaurant, but should you have to go to 11 different agencies? Who has the job of moving things along in Washington and making sure officials focus on real issues? That would be, uh, no one.

No one designed Washington’s giant bureaucracy either. It just grew, like kudzu, since the 1960s. Its organizing idea is to tell everyone exactly how to do everything correctly. Mindless compliance replaced human judgment. A new problem? Write another rule. The steady accretion of rules is why government has become progressively paralytic over the past few decades.

Back in the old days, of say, JFK or the late Sen. Majority Leader Howard Baker, government fixed problems by giving some official that job and then holding them accountable. Congress authorized the Interstate Highway System with a 29-page statute, and nine years later over 21,000 miles had been built. Today, the red tape would probably prevent it from being built at all.

It’s time to bite the bullet: Washington can’t be repaired; it must be replaced. Creating a coherent governing framework is not so daunting. Most bureaucratic detail is irrelevant when people are allowed to take responsibility again.

Instead of bickering over a laundry list of reforms, Americans should demand a few core principles:

* Radically simplify regulation. Law should set goals, not require mindless compliance with thousand-page rulebooks. Let Americans take responsibility and meet public goals in their own ways. More local control will not only work better but restore pride and self-respect.

* Accountability is key. Democracy is toothless without accountability. Accountability today is lost in legal quicksand and then strangled by public unions. Fairness should be protected with oversight, not exhausting lawsuits.

* Shake up Washington. Obsolete laws, bureaucratic stupor, partisan politics and lobbyists’ money all preserve the status quo. Reboot everything. Disrupt the electoral process by changing campaign rules. Move most agencies out of Washington — the bureaucratic culture there is toxic. Let the FDA go to Boston or San Diego. Send the worker safety agency to Ohio.

Experts say that change is impossible, pointing to the gridlock in Washington. Incremental change may be impossible, but big change is inevitable. Americans are fed up. That’s why they elected Donald Trump president and why Democrats are steering to the far left.

What’s missing is not public demand for change but a coherent vision of how Washington can work again. My proposal is basic: Replace the dense bureaucracy and put humans in charge again. Empower Americans, at all levels of responsibility, to make practical and moral daily choices. Then hold them accountable for how they do. Let Americans be American again.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, civic leader and writer, is chairman of Common Good and author of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left.

Philip K. Howard: Infrastructure repairs drown in regulatory molasses

To our readers: This column also ran in a pre-renovation version of New England Diary a few weeks ago. As we seek to import the pre-renovation archives, we will rerun particularly important files, such as Philip Howard's piece here.

-- Robert Whitcomb

By PHILIP K. HOWARD

NEW YORK

President Obama went on the stump this summer to promote his "Fix It First" initiative, calling for public appropriations to shore up America's fraying infrastructure. But funding is not the challenge. The main reason crumbling roads, decrepit bridges, antiquated power lines, leaky water mains and muddy harbors don't get fixed is interminable regulatory review.

Infrastructure approvals can take upward of a decade or longer, according to the Regional Plan Association. The environmental review statement for dredging the Savannah River took 14 years to complete. Even projects with little or no environmental impact can take years.

Raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge at the mouth of the Port of Newark, for example, requires no new foundations or right of way, and would not require approvals at all except that it spans navigable water. Raising the roadway would allow a new generation of efficient large ships into the port. But the project is now approaching its fifth year of legal process, bogged down in environmental litigation.

Mr. Obama also pitched infrastructure improvements in 2009 while he was promoting his $830 billion stimulus. The bill passed but nothing much happened because, as the administration learned, there is almost no such thing as a "shovel-ready project." So the stimulus money was largely diverted to shoring up state budgets.

Building new infrastructure would enhance U.S. global competitiveness, improve our environmental footprint and, according to McKinsey studies, generate almost two million jobs. But it is impossible to modernize America's physical infrastructure until we modernize our legal infrastructure. Regulatory review is supposed to serve a free society, not paralyze it.

Other developed countries have found a way. Canada requires full environmental review, with state and local input, but it has recently put a maximum of two years on major projects. Germany allocates decision-making authority to a particular state or federal agency: Getting approval for a large electrical platform in the North Sea, built this year, took 20 months; approval for the City Tunnel in Leipzig, scheduled to open next year, took 18 months. Neither country waits for years for a final decision to emerge out of endless red tape.

In America, by contrast, official responsibility is a kind of free-for-all among multiple federal, state and local agencies, with courts called upon to sort it out after everyone else has dropped of exhaustion. The effect is not just delay, but decisions skewed toward the squeaky wheels instead of the common good. This is not how democracy is supposed to work.

America is missing the key element of regulatory finality: No one is in charge of deciding when there has been enough review. Avoiding endless process requires changing the regulatory structure in two ways:

Environmental review today is done by a "lead agency"—such as the Coast Guard in the case of the Bayonne Bridge—that is usually a proponent of a project, and therefore not to be trusted to draw the line. Because it is under legal scrutiny and pressure to prove it took a "hard look," the lead agency's approach has mutated into a process of no pebble left unturned, followed by lawsuits that flyspeck documents that are often thousands of pages long.

What's needed is an independent agency to decide how much environmental review is sufficient. An alteration project like the Bayonne Bridge should probably have an environmental review of a few dozen pages and not, as in that case, more than 5,000 pages. If there were an independent agency with the power to say when enough is enough, then there would be a deliberate decision, not a multiyear ooze of irrelevant facts. Its decision on the scope of review can still be legally challenged as not complying with the basic principles of environmental law. But the challenge should come after, say, one year of review, not 10.

It is also important to change the Balkanized approvals process for other regulations and licenses. These approvals are now spread among federal, state and local agencies like a parody of bureaucracy, with little coordination and frequent duplication of environmental and other requirements. The Cape Wind project off the coast of Massachusetts, now in its 12th year of scrutiny, required review by 17 different agencies. The Gateway West power line, to carry electricity from Wyoming wind farms to the Pacific Northwest, requires the approval of each county in Idaho that the line will traverse. The approval process, begun in 2007, is expected to be complete by 2015. This is paralysis by federalism.

The solution is to create what other countries call "one-stop approvals." Giving one agency the authority to cut through the knot of multiple agencies (including those at state and local levels) will dramatically accelerate approvals.

This is how "greener" countries in Europe make decisions. In Germany, local projects are decided by a local agency (even if there's a national element), and national projects by a national agency (even though there are local concerns). One-stop approval is already in place in the U.S. New interstate gas pipelines are under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Special interests—especially groups that like the power of being able to stop anything—will foster fears of officials abusing the public trust. Giving people responsibility does not require trust, however. I don't trust anyone. But I can live with a system of democratic responsibility and judicial oversight. What our country can't live with is spinning our wheels in perpetual review. America needs to get moving again.

Philip K. Howard, a lawyer, is chairman of the nonpartisan reform group Common Good. His new book, "The Rule of Nobody," will be published in April by W.W. Norton. He is also the author of, among other works, "The Death of Common Sense''.