Fred Schulte: Medicare Advantage corruption in action

From Kaiser Family Health News

“CMS saving money for taxpayers isn’t enough of a reason to face the wrath of very powerful health plans.’’

Erin Fuse Brown, professor at the Brown University School of Public Health, in Providence

A decade ago, federal officials drafted a plan to discourage Medicare Advantage health insurers from overcharging the government by billions of dollars — only to abruptly back off amid an “uproar” from the industry, newly released court filings show.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services published the draft regulation in January 2014. The rule would have required health plans, when examining patient’s medical records, to identify overpayments by CMS and refund them to the government.

But in May 2014, CMS dropped the idea without any public explanation. Newly released court depositions show that agency officials repeatedly cited concern about pressure from the industry.

The 2014 decision by CMS, and events related to it, are at the center of a multibillion-dollar Justice Department civil fraud case against UnitedHealth Group pending in federal court in Los Angeles.

The Justice Department alleges the giant health insurer cheated Medicare out of more than $2 billion by reviewing patients’ records to find additional diagnoses, adding revenue while ignoring overcharges that might reduce bills. The company “buried its head in the sand and did nothing but keep the money,” DOJ said in a court filing.

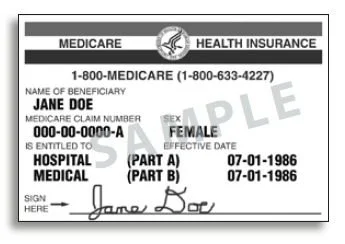

Medicare pays health plans higher rates for sicker patients but requires that the plans bill only for conditions that are properly documented in a patient’s medical records.

In a court filing, UnitedHealth Group denies wrongdoing and argues it shouldn’t be penalized for “failing to follow a rule that CMS considered a decade ago but declined to adopt.”

This month, the parties in the court case made public thousands of pages of depositions and other records that offer a rare glimpse inside the Medicare agency’s long-running struggle to keep the private health plans from taking taxpayers for a multibillion-dollar ride.

“It’s easy to dump on Medicare Advantage plans, but CMS made a complete boondoggle out of this,” said Richard Lieberman, a Colorado health data analytics expert.

Spokespeople for the Justice Department and CMS declined to comment for this article. In an email, UnitedHealth Group spokesperson Heather Soule said the company’s “business practices have always been transparent, lawful and compliant with CMS regulations.”

Missed Diagnoses

Medicare Advantage insurance plans have grown explosively in recent years and now enroll about 33 million members, more than half of people eligible for Medicare. Along the way, the industry has been the target of dozens of whistleblower lawsuits, government audits, and other investigations alleging the health plans often exaggerate how sick patients are to rake in undeserved Medicare payments — including by doing what are called chart reviews, intended to find allegedly missed diagnosis codes.

By 2013, CMS officials knew some Medicare health plans were hiring medical coding and analytics consultants to aggressively mine patient files — but they doubted the agency’s authority to demand that health plans also look for and delete unsupported diagnoses.

The proposed January 2014 regulation mandated that chart reviews “cannot be designed only to identify diagnoses that would trigger additional payments” to health plans.

CMS officials backed down in May 2014 because of “stakeholder concern and pushback,” Cheri Rice, then director of the CMS Medicare plan payment group, testified in a 2022 deposition made public this month. A second CMS official, Anne Hornsby, described the industry’s reaction as an “uproar.”

Exactly who made the call to withdraw the chart review proposal isn’t clear from court filings so far.

“The direction that we received was that the rule, the final rule, needed to include only those provisions that had wide, you know, widespread stakeholder support,” Rice testified.

“So we did not move forward then,” she said. “Not because we didn’t think it was the right thing to do or the right policy, but because it had mixed reactions from stakeholders.”

The CMS press office declined to make Rice available for an interview. Hornsby, who has since left the agency, declined to comment.

But Erin Fuse Brown, a professor at the Brown University School of Public Health, said the decision reflects a pattern of timid CMS oversight of the popular health plans for seniors.

“CMS saving money for taxpayers isn’t enough of a reason to face the wrath of very powerful health plans,” Fuse Brown said.

“That is extremely alarming.”

Invalid Codes

The fraud case against UnitedHealth Group, which runs the nation’s largest Medicare Advantage plan, was filed in 2011 by a former company employee. The DOJ took over the whistleblower suit in 2017.

DOJ alleges Medicare paid the insurer more than $7.2 billion from 2009 through 2016 solely based on chart reviews; the company would have received $2.1 billion less if it had deleted unsupported billing codes, the government says.

The government argues that UnitedHealth Group knew that many conditions it had billed for were not supported by medical records but chose to pocket the overpayments. For instance, the insurer billed Medicare nearly $28,000 in 2011 to treat a patient for cancer, congestive heart failure, and other serious health problems that weren’t recorded in the person’s medical record, DOJ alleged in a 2017 filing.

In all, DOJ contends that UnitedHealth Group should have deleted more than 2 million invalid codes.

Instead, company executives signed annual statements attesting that the billing data submitted to CMS was “accurate, complete, and truthful.” Those actions violated the False Claims Act, a federal law that makes it illegal to submit bogus bills to the government, DOJ alleges.

The complex case has featured years of legal jockeying, even pitting the recollections of key CMS staff members — including several who have since departed government for jobs in the industry — against those of UnitedHealthcare executives.

‘Red Herring’

Court filings describe a 45-minute video conference arranged by then-CMS administrator Marilyn Tavenner on April 29, 2014. Tavenner testified she set up the meeting between UnitedHealth and CMS staff at the request of Larry Renfro, a senior UnitedHealth Group executive, to discuss implications of the draft rule. Neither Tavenner nor Renfro attended.

Two UnitedHealth Group executives on the call said in depositions that CMS staffers told them the company had no obligation at the time to uncover erroneous codes. One of the executives, Steve Nelson, called it a “very clear answer” to the question. Nelson has since left the company.

For their part, four of the five CMS staffers on the call said in depositions that they didn’t remember what was said. Unlike the company’s team, none of the government officials took detailed notes.

“All I can tell you is I remember feeling very uncomfortable in the meeting,” Rice said in her 2022 deposition.

Yet Rice and one other CMS staffer said they did recall reminding the executives that even without the chart review rule, the company was obligated to make a good-faith effort to bill only for verified codes — or face possible penalties under the False Claims Act. And CMS officials reinforced that view in follow-up emails, according to court filings.

DOJ called the flap over the ill-fated regulation a “red herring” in a court filing and alleges that when UnitedHealth asked for the April 2014 meeting, it knew its chart reviews had been under investigation for two years. In addition, the company was “grappling with a projected $500 million budget deficit,” according to DOJ.

Data Miners

Medicare Advantage plans defend chart reviews against criticism that they do little but artificially inflate the government’s costs.

“Chart reviews are one of many tools Medicare Advantage plans use to support patients, identify chronic conditions, and prevent those conditions from becoming more serious,” said Chris Bond, a spokesperson for AHIP, a health insurance trade group.

Whistleblowers have argued that the cottage industry of analytics firms and coders that sprang up to conduct these reviews pitched their services as a huge moneymaking exercise for health plans — and little else.

“It was never legitimate,” said William Hanagami, a California attorney who represented whistleblower James Swoben in a 2009 case that alleged chart reviews improperly inflated Medicare payments. In a 2016 decision, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals wrote that health plans must exercise “due diligence” to ensure they submit accurate data.

Since then, other insurers have settled DOJ allegations that they billed Medicare for unconfirmed diagnoses stemming from chart reviews. In July 2023, Martin’s Point Health Plan, a Portland, Maine, insurer, paid $22,485,000 to settle whistleblower allegations that it improperly billed for conditions ranging from diabetes with complications to morbid obesity. The plan denied any liability.

A December 2019 report by the Health and Human Services Inspector General found that 99% of chart reviews added new medical diagnoses at a cost to Medicare of an estimated $6.7 billion for 2017 alone.

Fred Schulte is a Kaiser Family Foundation health news reporter.

Susan Jaffe: Feds rein in Medical Advantage predictive software

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

Judith Sullivan was recovering from major surgery at a Connecticut nursing home in March when she got surprising news from her Medicare Advantage plan: It would no longer pay for her care because she was well enough to go home.

At the time, she could not walk more than a few feet, even with assistance — let alone manage the stairs to her front door, she said. She still needed help using a colostomy bag following major surgery.

“How could they make a decision like that without ever coming and seeing me?” said Sullivan, 76. “I still couldn’t walk without one physical therapist behind me and another next to me. Were they all coming home with me?”

UnitedHealthcare — the nation’s largest health-insurance company, which provides Sullivan’s Medicare Advantage plan — doesn’t have a crystal ball. It does have naviHealth, a care-management company bought by UHC’s sister company, Optum, in 2020. Both are part of UnitedHealth Group. NaviHealth analyzes data to help UHC and other insurance companies make coverage decisions.

Its proprietary “nH Predict” tool sifts through millions of medical records to match patients with similar diagnoses and characteristics, including age, preexisting health conditions, and other factors. Based on these comparisons, an algorithm anticipates what kind of care a specific patient will need and for how long.

But patients, providers, and patient advocates in several states said they have noticed a suspicious coincidence: The tool often predicts a patient’s date of discharge, which coincides with the date their insurer cuts off coverage, even if the patient needs further treatment that government-run Medicare would provide.

“When an algorithm does not fully consider a patient’s needs, there’s a glaring mismatch,” said Rajeev Kumar, a physician and the president-elect of the Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, which represents long-term care practitioners. “That’s where human intervention comes in.”

The federal government will try to even the playing field next year, when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services begins restricting how Medicare Advantage plans use predictive technology tools to make some coverage decisions.

Medicare Advantage plans, an alternative to the government-run, original Medicare program, are operated by private insurance companies. About half the people eligible for full Medicare benefits are enrolled in the private plans, attracted by their lower costs and enhanced benefits like dental care, hearing aids, and a host of nonmedical extras like transportation and home-delivered meals.

Insurers receive a monthly payment from the federal government for each enrollee, regardless of how much care they need. According to the Department of Health and Human Services’ inspector general, this arrangement raises “the potential incentive for insurers to deny access to services and payment in an attempt to increase profits.” Nursing home care has been among the most frequently denied services by the private plans — something original Medicare likely would cover, investigators found.

After UHC cut off her nursing home coverage, Sullivan’s medical team agreed with her that she wasn’t ready to go home and provided an additional 18 days of treatment. Her bill came to $10,406.36.

Beyond her mobility problems, “she also had a surgical wound that needed daily dressing changes” when UHC stopped paying for her nursing home care, said Debra Samorajczyk, a registered nurse and the administrator at the Bishop Wicke Health and Rehabilitation Center, in Shelton, Conn., the facility that treated Sullivan.

Sullivan’s coverage denial notice and nH Predict report did not mention wound care or her inability to climb stairs. Original Medicare would have most likely covered her continued care, said Samorajczyk.

Sullivan appealed twice but lost. Her next appeal was heard by an administrative law judge, who holds a courtroom-style hearing usually by phone or video link, in which all sides can provide testimony. UHC declined to send a representative, but the judge nonetheless sided with the company. Sullivan is considering whether to appeal to the next level, the Medicare Appeals Council, and the last step before the case can be heard in federal court.

Sullivan’s experience is not unique. In February, Ken Drost’s Medicare Advantage plan, provided by Security Health Plan of Wisconsin, wanted to cut his coverage at a Wisconsin nursing home after 16 days, the same number of days naviHealth predicted was necessary. But Drost, 87, who was recovering from hip surgery, needed help getting out of bed and walking. He stayed at the nursing home for an additional week, at a cost of $2,624.

After he appealed twice and lost, his hearing on his third appeal was about to begin when his insurer agreed to pay his bill, said his lawyer, Christine Huberty, supervising attorney at the Greater Wisconsin Agency on Aging Resources Elder Law & Advocacy Center in Madison.

“Advantage plans routinely cut patients’ stays short in nursing homes,” she said, including Humana, Aetna, Security Health Plan, and UnitedHealthcare. “In all cases, we see their treating medical providers disagree with the denials.”

UnitedHealthcare and naviHealth declined requests for interviews and did not answer detailed questions about why Sullivan’s nursing home coverage was cut short over the objections of her medical team.

Aaron Albright, a naviHealth spokesperson, said in a statement that the nH Predict algorithm is not used to make coverage decisions and instead is intended “to help the member and facility develop personalized post-acute care discharge planning.” Length-of-stay predictions “are estimates only.”

However, naviHealth’s website boasts about saving plans money by restricting care. The company’s “predictive technology and decision support platform” ensures that “patients can enjoy more days at home, and healthcare providers and health plans can significantly reduce costs specific to unnecessary care and readmissions.”

New federal rules for Medicare Advantage plans beginning in January will rein in their use of algorithms in coverage decisions. Insurance companies using such tools will be expected to “ensure that they are making medical necessity determinations based on the circumstances of the specific individual,” the requirements say, “as opposed to using an algorithm or software that doesn’t account for an individual’s circumstances.”

The CMS-required notices nursing home residents receive now when a plan cuts short their coverage can be oddly similar while lacking details about a particular resident. Sullivan’s notice from UHC contains some identical text to the one Drost received from his Wisconsin plan. Both say, for example, that the plan’s medical director reviewed their cases, without providing the director’s name or medical specialty. Both omit any mention of their health conditions that make managing at home difficult, if not impossible.

The tools must still follow Medicare coverage criteria and cannot deny benefits that original Medicare covers. If insurers believe the criteria are too vague, plans can base algorithms on their own criteria, as long as they disclose the medical evidence supporting the algorithms.

And before denying coverage considered not medically necessary, another change requires that a coverage denial “must be reviewed by a physician or other appropriate health care professional with expertise in the field of medicine or health care that is appropriate for the service at issue.”

Jennifer Kochiss, a social worker at Bishop Wicke who helps residents file insurance appeals, said patients and providers have no say in whether the doctor reviewing a case has experience with the client’s diagnosis. The new requirement will close “a big hole,” she said.

The leading MA plans oppose the changes in comments submitted to CMS. Tim Noel, UHC’s CEO for Medicare and retirement, said MA plans’ ability to manage beneficiaries’ care is necessary “to ensure access to high-quality safe care and maintain high member satisfaction while appropriately managing costs.”

Restricting “utilization management tools would markedly deviate from Congress’ intent in creating Medicare managed care because they substantially limit MA plans’ ability to actually manage care,” he said.

In a statement, UHC spokesperson Heather Soule said the company’s current practices are “consistent” with the new rules. “Medical directors or other appropriate clinical personnel, not technology tools, make all final adverse medical necessity determinations” before coverage is denied or cut short. However, these medical professionals work for UHC and usually do not examine patients. Other insurance companies follow the same practice.

David Lipschutz, associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy, is concerned about how CMS will enforce the rules since it doesn’t mention specific penalties for violations.

CMS’ deputy administrator and director of the Medicare program, Meena Seshamani, said that the agency will conduct audits to verify compliance with the new requirements, and “will consider issuing an enforcement action, such as a civil money penalty or an enrollment suspension, for the non-compliance.”

Although Sullivan stayed at Bishop Wicke after UHC stopped paying, she said another resident went home when her MA plan wouldn’t pay anymore. After two days at home, the woman fell, and an ambulance took her to the hospital, Sullivan said. “She was back in the nursing home again because they put her out before she was ready.”

Susan Jaffe is Kaiser Family Foundation reporter.