Michelle Andrews: Fertility treatment can be out of reach for the poor

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“This is really sort of standing out as a sore thumb in a nation that would like to claim that it cares for the less fortunate and it seeks to do anything it can for them.’’

— Eli Adashi, a professor of medical science at Brown University and former president of the Society for Reproductive Endocrinologists.

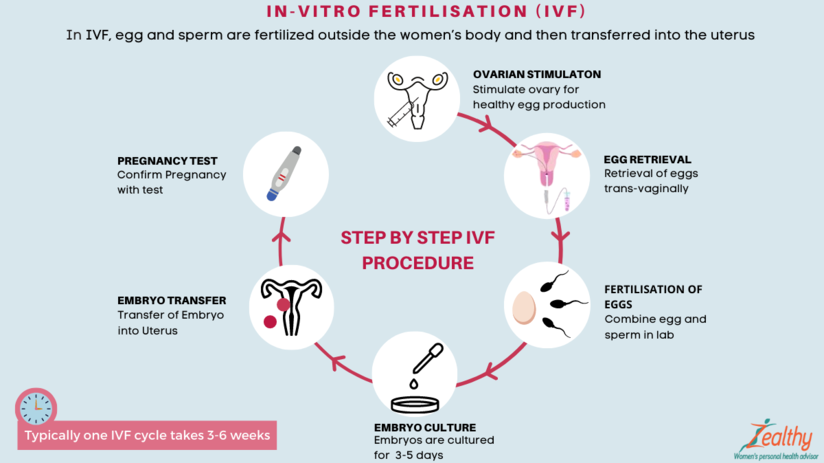

Mary Delgado’s first pregnancy went according to plan, but when she tried to get pregnant again seven years later, nothing happened. After 10 months, Delgado, now 34, and her partner, Joaquin Rodriguez, went to see an OB-GYN. Tests showed she had endometriosis, which was interfering with conception. Delgado’s only option, the doctor said, was in vitro fertilization.

“When she told me that, she broke me inside,” Delgado said, “because I knew it was so expensive.”

Delgado, who lives in New York City, is enrolled in Medicaid, the federal-state health program for low-income and disabled people. The roughly $20,000 price tag for a round of IVF would be a financial stretch for lots of people, but for someone on Medicaid — for which the maximum annual income for a two-person household in New York is just over $26,000 — the treatment can be unattainable.

Expansions of work-based insurance plans to cover fertility treatments, including free egg freezing and unlimited IVF cycles, are often touted by large companies as a boon for their employees. But people with lower incomes, often minorities, are more likely to be covered by Medicaid or skimpier commercial plans with no such coverage. That raises the question of whether medical assistance to create a family is only for the well-to-do or people with generous benefit packages.

“In American health care, they don’t want the poor people to reproduce,” Delgado said. She was caring full-time for their son, who was born with a rare genetic disorder that required several surgeries before he was 5. Her partner, who works for a company that maintains the city’s yellow cabs, has an individual plan through the state insurance marketplace, but it does not include fertility coverage.

Years after she had her first child, Joaquin , Mary Delgado found out that she had endometriosis and that IVF was her only option to get pregnant again. The news from her doctor “broke me inside,” Delgado says, “because I knew it was so expensive.” Delgado, who is on Medicaid, traveled more than 300 miles round trip for lower-cost IVF, and she and her partner, Joaquin Rodriguez, used savings they’d set aside for a home. Their daughter, Emiliana, is now almost a year old.

Some medical experts whose patients have faced these issues say they can understand why people in Delgado’s situation think the system is stacked against them.

“It feels a little like that,” said Elizabeth Ginsburg, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Harvard Medical School who is president-elect of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, a research and advocacy group.

Whether or not it’s intended, many say the inequity reflects poorly on the U.S.

“This is really sort of standing out as a sore thumb in a nation that would like to claim that it cares for the less fortunate and it seeks to do anything it can for them,” said Eli Adashi, a professor of medical science at Brown University and former president of the Society for Reproductive Endocrinologists.

Yet efforts to add coverage for fertility care to Medicaid face a lot of pushback, Ginsburg said.

Over the years, Barbara Collura, president and CEO of the advocacy group Resolve: The National Infertility Association, has heard many explanations for why it doesn’t make sense to cover fertility treatment for Medicaid recipients. Legislators have asked, “If they can’t pay for fertility treatment, do they have any idea how much it costs to raise a child?” she said.

“So right there, as a country we’re making judgments about who gets to have children,” Collura said.

The legacy of the eugenics movement of the early 20th century, when states passed laws that permitted poor, nonwhite, and disabled people to be sterilized against their will, lingers as well.

“As a reproductive justice person, I believe it’s a human right to have a child, and it’s a larger ethical issue to provide support,” said Regina Davis Moss, president and CEO of In Our Own Voice: National Black Women’s Reproductive Justice Agenda, an advocacy group.

But such coverage decisions — especially when the health care safety net is involved — sometimes require difficult choices, because resources are limited.

Even if state Medicaid programs wanted to cover fertility treatment, for instance, they would have to weigh the benefit against investing in other types of care, including maternity care, said Kate McEvoy, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “There is a recognition about the primacy and urgency of maternity care,” she said.

Medicaid pays for about 40 percent of births in the United States. And since 2022, 46 states and the District of Columbia have elected to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months, up from 60 days.

Fertility problems are relatively common, affecting roughly 10% of women and men of childbearing age, according to the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Traditionally, a couple is considered infertile if they’ve been trying to get pregnant unsuccessfully for 12 months. Last year, the ASRM broadened the definition of infertility to incorporate would-be parents beyond heterosexual couples, including people who can’t get pregnant for medical, sexual, or other reasons, as well as those who need medical interventions such as donor eggs or sperm to get pregnant.

The World Health Organization defined infertility as a disease of the reproductive system characterized by failing to get pregnant after a year of unprotected intercourse. It terms the high cost of fertility treatment a major equity issue and has called for better policies and public financing to improve access.

No matter how the condition is defined, private health plans often decline to cover fertility treatments because they don’t consider them “medically necessary.” Twenty states and Washington, D.C., have laws requiring health plans to provide some fertility coverage, but those laws vary greatly and apply only to companies whose plans are regulated by the state.

In recent years, many companies have begun offering fertility treatment in a bid to recruit and retain top-notch talent. In 2023, 45 percent of companies with 500 or more workers covered IVF and/or drug therapy, according to the benefits consultant Mercer.

But that doesn’t help people on Medicaid. Only two states’ Medicaid programs provide any fertility treatment: New York covers some oral ovulation-enhancing medications, and Illinois covers costs for fertility preservation, to freeze the eggs or sperm of people who need medical treatment that will likely make them infertile, such as for cancer. Several other states also are considering adding fertility preservation services.

In Delgado’s case, Medicaid covered the tests to diagnose her endometriosis, but nothing more. She was searching the internet for fertility treatment options when she came upon a clinic group called CNY Fertility that seemed significantly less expensive than other clinics, and also offered in-house financing. Based in Syracuse, New York, the company has a handful of clinics in upstate New York cities and four other U.S. locations.

Though Delgado and her partner had to travel more than 300 miles round trip to Albany for the procedures, the savings made it worthwhile. They were able do an entire IVF cycle, including medications, egg retrieval, genetic testing, and transferring the egg to her uterus, for $14,000. To pay for it, they took $7,000 of the cash they’d been saving to buy a home and financed the other half through the fertility clinic.

She got pregnant on the first try, and their daughter, Emiliana, is now almost a year old.

Delgado doesn’t resent people with more resources or better insurance coverage, but she wishes the system were more equitable.

“I have a medical problem,” she said. “It’s not like I did IVF because I wanted to choose the gender.”

One reason CNY is less expensive than other clinics is simply that the privately owned company chooses to charge less, said William Kiltz, its vice president of marketing and business development. Since the company’s beginning in 1997, it has become a large practice with a large volume of IVF cycles, which helps keep prices low.

At this point, more than half its clients come from out of state, and many earn significantly less than a typical patient at another clinic. Twenty percent earn less than $50,000, and “we treat a good number who are on Medicaid,” Kiltz said.

Now that their son, Joaquin, is settled in a good school, Delgado has started working for an agency that provides home health services. After putting in 30 hours a week for 90 days, she’ll be eligible for health insurance.

Michelle Andrews: is a Kaiser Family Health News contributing writer.

andrews.khn@gmail.com, @mandrews110

Hannah Recht: Many losing Medicaid coverage because they don’t complete paperwork

Green states have adopted Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act .

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFF Health News)

“{W}e need to change up our strategy.’’

— Henry Lipman, New Hampshire’s Medicaid director

More than 600,000 Americans have lost Medicaid coverage since pandemic protections ended on April 1. And a KFF Health News analysis of state data shows the vast majority were removed from state rolls for not completing paperwork.

We have published the underlying reports that contain the data used in this article so that local reporters, researchers, and others can explore state data on Medicaid renewals in more detail.

Under normal circumstances, states review their Medicaid enrollment lists regularly to ensure every recipient qualifies for coverage. But because of a nationwide pause in those reviews during the pandemic, the health insurance program for low-income and disabled Americans kept people covered even if they no longer qualified.

Now, in what’s known as the Medicaid unwinding, states are combing through rolls and deciding who stays and who goes. People who are no longer eligible or don’t complete paperwork in time will be dropped.

The overwhelming majority of people who have lost coverage in most states were dropped because of technicalities, not because state officials determined they no longer meet Medicaid income limits. Four out of every five people dropped so far either never returned the paperwork or omitted required documents, according to a KFF Health News analysis of data from 11 states that provided details on recent cancellations. Now, lawmakers and advocates are expressing alarm over the volume of people losing coverage and, in some states, calling to pause the process.

KFF Health News sought data from the 19 states that started cancellations by May 1. Based on records from 14 states that provided detailed numbers, either in response to a public records request or by posting online, 36 percent of people whose eligibility was reviewed have been disenrolled.

In Indiana, 53,000 residents lost coverage in the first month of the unwinding, 89 percent for procedural reasons like not returning renewal forms. State Rep. Ed Clere, a Republican, expressed dismay at those “staggering numbers” in a May 24 Medicaid advisory group meeting, repeatedly questioning state officials about forms mailed to out-of-date addresses and urging them to give people more than two weeks’ notice before canceling their coverage.

Clere warned that the cancellations set in motion an avoidable revolving door. Some people dropped from Medicaid will have to forgo filling prescriptions and cancel doctor visits because they can’t afford care. Months down the line, after untreated chronic illnesses spiral out of control, they’ll end up in the emergency room where social workers will need to again help them join the program, he said.

Before the unwinding, more than 1 in 4 Americans — 93 million — were covered by Medicaid or CHIP, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, according to KFF Health News’ analysis of the latest enrollment data. Half of all kids are covered by the programs.

About 15 million people will be dropped over the next year as states review participants’ eligibility in monthly tranches.

Most people will find health coverage through new jobs or qualify for subsidized plans through the Affordable Care Act. But millions of others, including many children, will become uninsured and unable to afford basic prescriptions or preventive care. The uninsured rate among those under 65 is projected to rise from a historical low of 8.3% today to 9.3% next year, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Because each state is handling the unwinding differently, the share of enrollees dropped in the first weeks varies widely.

Several states are first reviewing people officials believe are no longer eligible or who haven’t recently used their insurance. High cancellation rates in those states should level out as the agencies move on to people who likely still qualify.

In Utah, nearly 56 percent of people included in early reviews were dropped. In New Hampshire, 44 percent received cancellation letters within the first two months — almost all for procedural reasons, like not returning paperwork.

But New Hampshire officials found that thousands of people who didn’t fill out the forms indeed earn too much to qualify, according to Henry Lipman, the state’s Medicaid director. They would have been denied anyway. Even so, more people than he expected are not returning renewal forms. “That tells us that we need to change up our strategy,” said Lipman.

In other states, like Virginia and Nebraska, which aren't prioritizing renewals by likely eligibility, about 90 percent have been renewed.

Because of the three-year pause in renewals, many people on Medicaid have never been through the process or aren’t aware they may need to fill out long verification forms, as a recent KFF poll found. Some people moved and didn’t update their contact information.

And while agencies are required to assist enrollees who don’t speak English well, many are sending the forms in only a few common languages.

Tens of thousands of children are losing coverage, as researchers have warned, even though some may still qualify for Medicaid or CHIP. In its first month of reviews, South Dakota ended coverage for 10% of all Medicaid and CHIP enrollees in the state. More than half of them were children. In Arkansas, about 40% were kids.

Many parents don’t know that limits on household income are significantly higher for children than adults. Parents should fill out renewal forms even if they don’t qualify themselves, said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families.

New Hampshire has moved most families with children to the end of the review process. Lipman, the state’s Medicaid director, said his biggest worry is that a child will end up uninsured. Florida also planned to push kids with serious health conditions and other vulnerable groups to the end of the review line.

But according to Miriam Harmatz, advocacy director and founder of the Florida Health Justice Project, state officials sent cancellation letters to several clients with disabled children who probably still qualify. She’s helping those families appeal.

Nearly 250,000 Floridians reviewed in the first month of the unwinding lost coverage, 82 percent of them for reasons like incomplete paperwork, the state reported to federal authorities. House Democrats from the state petitioned Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis to pause the unwinding.

Advocacy coalitions in both Florida and Arkansas also have called for investigations into the review process and a pause on cancellations.

The state is contacting enrollees by phone, email, and text, and continues to process late applications, said Tori Cuddy, a spokesperson for the Florida Department of Children and Families. Cuddy did not respond to questions about issues raised in the petitions.

Federal officials are investigating those complaints and any other problems that emerge, said Dan Tsai, director of the Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services. “If we find that the rules are not being followed, we will take action.”

His agency has directed states to automatically reenroll residents using data from other government programs like unemployment and food assistance when possible. Anyone who can’t be approved through that process must act quickly.

“For the past three years, people have been told to ignore the mail around this, that the renewal was not going to lead to a termination.” Suddenly that mail matters, he said.

Federal law requires states to tell people why they’re losing Medicaid coverage and how to appeal the decision.

Harmatz said some cancellation notices in Florida are vague and could violate due process rules. Letters that she’s seen say “your Medicaid for this period is ending” rather than providing a specific reason for disenrollment, like having too high an income or incomplete paperwork.

If a person requests a hearing before their cancellation takes effect, they can stay covered during the appeals process. Even after being disenrolled, many still have a 90-day window to restore coverage.

In New Hampshire, 13% of people deemed ineligible in the first month have asked for extra time to provide the necessary records. “If you're eligible for Medicaid, we don't want you to lose it,” said Lipman.

Clere, the Indiana state representative, pushed his state’s Medicaid officials during the May meeting to immediately make changes to avoid people unnecessarily becoming uninsured. One official responded that they’ll learn and improve over time.

“I’m just concerned that we’re going to be ‘learning’ as a result of people losing coverage,” Clere replied. “So I don’t want to learn at their expense.”

Hannah Recht is a KFF Health News reporter.

#Medicaid

Judith Graham: In Maine and elsewhere, many elderly struggle to pay for basic necessities

Farmer's market in Monument Square, downtown Portland

— Photo by vBd2media

Townhouses in Portland’s West End, completed in 1835

— Photo by Motionhero

PORTLAND, Maine

Fran Seeley, 81, doesn’t see herself as living on the edge of a financial crisis. But she’s uncomfortably close.

Each month, Seeley, a retired teacher, gets $925 from Social Security and a $287 disbursement from an individual retirement account. To make ends meet, she’s taken out a reverse mortgage on her home here that yields $400 monthly.

So far, Seeley has been able to live on this income — about $19,300 a year — by carefully monitoring her spending and drawing on limited savings. But should her excellent health worsen or she need assistance at home, Seeley doesn’t know how she’d pay for those expenses.

More than half of older women living alone — 54% — are in a similarly precarious financial situation: either poor according to federal poverty standards or with incomes too low to pay for essential expenses. For single men, the share is lower but still surprising — 45%.

That’s according to a valuable but little-known measure of the cost of living for older adults: the Elder Index, developed by researchers at the Gerontology Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Boston.

A new coalition, the Equity in Aging Collaborative, is planning to use the index to influence policies that affect older adults, such as property tax relief and expanded eligibility for programs that assist with medical expenses. Twenty-five prominent aging organizations are members of the collaborative.

The goal is to fuel a robust dialogue about “the true cost of aging in America,” which remains unappreciated, said Ramsey Alwin, president and chief executive of the National Council on Aging, an organizer of the coalition.

Nationally, and for every state and county in the U.S., the Elder Index uses various public databases to calculate the cost of health care, housing, food, transportation and miscellaneous expenses for seniors. It represents a bare-bones budget, adjusted for whether older adults live alone or as part of a couple; whether they’re in poor, good or excellent health; and whether they rent or own homes, with or without a mortgage.

Results from the analyses are eye-opening. In 2020, according to data supplied by Jan Mutchler, director of the Gerontology Institute, the index shows that nearly 5 million older women living alone, 2 million older men living alone, and more than 2 million older couples had incomes that made them economically insecure.

And those estimates were before inflation soared to more than 9% — a 40-year high — and older adults continued to lose jobs during the second and third years of the pandemic. “With those stressors layered on, even more people are struggling,” Mutchler said.

Nationally and in every state, the minimum cost of living for older adults calculated by the Elder Index far exceeds federal poverty thresholds, which are used to calculate official poverty statistics. (Federal poverty thresholds used by the Elder Index differ slightly from federal poverty guidelines. Data for each state can be found here.)

One national example: The Elder Index estimates that a single older adult in good health paying rent needed $27,096, on average, for basic expenses in 2021 — $14,100 more than the federal poverty threshold of $12,996. For couples, the gap between the index’s calculation of necessities and the poverty threshold was even greater.

Yet eligibility for Medicaid, food stamps, housing assistance and other safety-net programs that help older adults is based on federal poverty standards, which don’t account for geographic variations in the cost of living or medical expenses incurred by older adults, among other factors. (This isn’t an issue for older adults alone; the poverty measures have been widely critiqued across age groups.)

“The poverty rate just doesn’t cut it as a realistic look at the struggles older adults are having,” said William Arnone, chief executive officer of the National Academy of Social Insurance, one of the new coalition’s members. “The Elder Index is a reality check.”

In April, University of Massachusetts researchers showed that Social Security benefits cover only a fraction of what older adults need for basic living expenses: 68% for a senior in good health who lives alone and pays rent and 81% for an older couple in the same situation.

“There’s a myth that Social Security and Medicare miraculously take care of all of people’s needs in older age,” said Alwin, of the National Council on Aging. “The reality is they don’t, and far too many people are one crisis away from economic insecurity.”

Organizations across the country have been using the Elder Index to convince policymakers that older adults need more assistance. In New Jersey, where 54% of seniors are economically insecure according to the index, advocates used the data to protect property-tax relief programs for older adults during the pandemic. In New York, where nearly 60% of seniors are economically insecure, advocates persuaded the legislature to raise the Medicaid income eligibility threshold.

In San Diego, where as many as 40% of seniors are economically insecure, Serving Seniors, a nonprofit agency, persuaded county officials to use pandemic-related stimulus payments to expand senior nutrition programs. As a result, the agency has been able to double production of home-delivered meals, to more than 1.5 million annually.

Officials are often wary of the financial impact of expanding programs, said Paul Downey, president and CEO of Serving Seniors. But, he said, “we should be using a reliable measure of economic security and at least know how well the programs we’re offering are doing.” By law, California’s Area Agencies on Aging use the Elder Index in their planning process.

Maine is No. 5 on the list of states ranked by the share of seniors living below the Elder Index, 56%. For someone in Fran Seeley’s situation (an older adult who is in excellent health, lives alone, owns a house, and doesn’t pay a monthly mortgage), the index suggests $22,560 a year is necessary — $3,200 more than Seeley’s annual income and $9,500 above the federal poverty threshold.

Fran Seeley’s income — from Social Security, a retirement account, and a reverse mortgage — comes to about $19,300 a year. With inflation increasing, “it means I have to cut back in any way I can,” Seeley says.

A look at Seeley’s budget reveals how quickly necessary expenses accumulate: $2,041 annually for Medicare Part B (this is deducted from her Social Security check), $4,156 for property and stormwater taxes, $390 for home insurance, $320 for furnace cleaning, $1,440 for heat, $125 for water, $500 for gas and electricity, $300 for property maintenance, $1,260 for phone and Internet, $150 for car registration, $640 for car insurance, $840 for gasoline at current prices, $300 for car maintenance, and $4,800 for food.

The total: $17,262. And that doesn’t include the cost of medications, clothing, toiletries, any kind of entertainment, or other incidentals.

Seeley’s great luxury is caring for four cats, which she describes as “the light of my life.” Their annual wellness checks cost about $400 a year, while their food costs about $1,080.

With inflation now making her budget even tighter, “it means I have to cut back in any way I can. I find myself going into stores and saying, ‘No, I don’t need that,’” Seeley said. “The biggest worry I have is not being able to afford living in my home or becoming ill. I know that medical expenses could wipe me out in no time financially.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News Reporter.

Phil Galewitz: ACA co-ops soon down to three, including one in Maine

New Mexico Health Connections’ decision to close at year’s end will leave just three of the 23 nonprofit health-insurance co-ops that sprang from the Affordable Care Act.

One co-op serves customers in Maine, another in Wisconsin, and the third operates in Idaho and Montana and will move into Wyoming next year. All made money in 2019 after having survived several rocky years, according to data filed with the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

They are also all in line to receive tens of millions of dollars from the federal government under an April Supreme Court ruling that said the government inappropriately withheld billions from insurers meant to help cushion losses from 2014 through 2016, the first three years of the ACA marketplaces. While those payments were intended to help any insurers losing money, it was vitally important to the co-ops because they had the least financial backing.

Lauded as a way to boost competition among insurers and hold down prices on the Obamacare exchanges, the co-ops had more than 1 million people enrolled in 26 states at their peak in 2015. Today, they cover about 128,000 people, just 1% of the 11 million Obamacare enrollees who get coverage through the exchanges.

The nonprofit organizations were a last-minute addition to the 2010 health law to satisfy Democratic lawmakers who had failed to secure a public option health plan — one set up and run by the government — on the marketplaces. Congress provided $2 billion in startup loans. But nearly all the co-ops struggled to compete with established carriers, which already had more money and recognized brands.

State insurance officials and health experts are hopeful that the last three co-ops will survive.

“These are the three little miracles,” said Sabrina Corlette, a research professor and co-director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University, in Washington, D.C.

Maine Aided in Supreme Court Victory

The Maine co-op, Community Health Options, helped bring competition to the state’s market, which has had trouble at times attracting insurance carriers, said Eric Cioppa, who heads the state’s bureau of insurance.

“The plan has added a level of stability and has been a positive for Maine,” he said.

The co-op has about 28,000 members — down from about 75,000 in 2015 — and is building up its financial reserves, Cioppa said. Community Health Options is one of three insurers in the Obamacare marketplace in Maine, the minimum number experts say is needed to ensure vibrant competition.

Kevin Lewis, CEO of the plan, attributed its survival to several factors, including an initial profit in 2014, the year the ACA marketplaces opened, that put the plan on a secure footing before several years of losses. He also credited bringing most functions of the health plan in-house rather than contracting out, diversifying to sell plans to small and large employers, and securing lower rates from two health systems during a couple of difficult years.

Jay Gould, 60, a member who offers the plan to workers at his small grocery store in Clinton, has been happy with the plan. “They have great customer service, and it’s good to know when I am talking to someone that they are from Maine,” he said.

Central Aroostook Association, a Presque Isle nonprofit that helps children with intellectual disabilities, switched to the co-op last year to save 20% on its health premiums, said administrator Tammi Easler. Having a Maine insurer means any issues can be dealt with quickly, she said. “They are readily available, and I never have to wait on hold for an hour.”

The co-op, which made a $25 million profit each of the past two years, has proposed dropping its average premiums by about 14% in 2021, Lewis said.

Community Health was one of the lead plaintiffs in the case before the Supreme Court and expects to get $59 million in back payments from the settlement.

The federal decision to suspend those so-called risk corridor payments — designed to help health plans recover some of their losses — was one of the factors that caused many of the co-ops to fail, Corlette said. Republican critics of the ACA, however, blame poor management by the plans and lack of oversight by the Obama administration.

Insurers are in talks with the Trump administration about whether the $13 billion due the carriers must be added to their 2020 balance sheet or could be counted toward operations from prior years. This year, insurers are generally banking large profits since many people have delayed non-urgent care because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the ACA limits insurers’ profit margins, adding that federal windfall to this year’s ledger might mean many insurers would have to pay out most of the money to their consumers. If the money is applied to earlier years, the insurers could likely keep more of it to add to their reserves.

Too Much Competition in New Mexico

The Supreme Court ruling came too late for New Mexico Health Connections, which lost nearly $60 million from 2015 to 2017. The co-op would have received $43 million in overdue payments, but, in an effort to raise needed cash, it sold that debt to another insurer in 2017 for a much smaller amount.

Marlene Baca, CEO of the co-op, which made a $439,000 profit in 2019, said its goal of bringing competition into the market was achieved, since five other companies will be enrolling customers this fall for 2021. Yet, that competition eventually led to the plan’s decision to end operations, announced last month.

With only 14,000 members, it made no sense to continue operating due to high fixed administrative costs, she said. Her plan was also hurt by the slumping economy this year, which pushed many state residents out of work and made more than 3,000 members eligible for Medicaid, the state-federal health program for the poor.

“We did our very best,” Baca said, noting that her company is closing with enough money to pay its outstanding health claims. Many other co-ops that shuttered were closed out by their states and unable to meet all their debts to health providers, she said.

Montana’s Co-Op Is Expanding

The Mountain Health Co-Op, with about 32,000 members, has just two competitors in its home state of Montana and four in Idaho.

A big factor behind its survival was that the plan received a $15 million loan in 2016 from St. Luke’s Health System, Idaho’s largest hospital provider, said CEO Richard Miltenberger. Although he wasn’t working for the co-op at that time, Miltenberger said, it is his understanding that the hospital wanted to help maintain competition in that marketplace.

The co-op is expecting $57 million from the Supreme Court victory.

“We are in excellent shape,” Miltenberger said. The plan, which paid back the St. Luke’s loan and made a $15 million profit in 2019, added vision benefits this year and is offering a dental exam benefit for next year. It’s also providing most insulin and medications for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to members without any copayment to help ensure compliance.

The insurer is moving into Wyoming for 2021, which will end the Blue Cross plan monopoly in that state’s Obamacare marketplace, he said.

Wisconsin’s Mystery Donor

Wisconsin’s Common Ground Healthcare Cooperative was on the verge of ending operations in 2016 when it received a lifesaving $30 million loan, said CEO Cathy Mahaffey. The insurer has refused to identify the benefactor other than to say it was not a person or company doing business with the plan.

In 2018, Common Ground was the only health plan in seven northeastern Wisconsin counties, she said. Today, the co-op has about 54,000 members and faces competition from two to five carriers in the 20 counties where it operates.

Common Ground, which recorded a $73 million profit last year, expects to receive about $95 million from the Supreme Court case victory.

Wisconsin’s decision not to expand Medicaid under the health law has benefited the co-op because people with incomes from 100% to 138% of the federal poverty level ($12,760 to $17,609 for an individual) are ineligible for Medicaid and must stay with marketplace plans for coverage. In states that expanded Medicaid, everyone with incomes under 138% of the poverty level is eligible.

Another factor was its decision in 2016 to eliminate the broad provider network offering and sell a plan offering only a narrow network of doctors and hospitals, allowing it to benefit from lower rates from its providers, according to Mahaffey.

“We are very strong financially,” she said.

Phil Galewitz is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Julie Appleby: Whither hospital-at-home services after pandemic?

After seven days as an inpatient for complications related to heart problems, Glenn Shanoski was initially hesitant when doctors suggested in early April that he could cut his hospital stay short and recover at home — with high-tech 24-hour monitoring and daily visits from medical teams.

But Shanoski, a 52-year-old electrician in Salem, Mass., decided to give it a try. He’d felt increasingly lonely in a hospital where the COVID-19 pandemic meant no visitors. Also, Boston’s Tufts Medical Center wanted to free up beds for a possible surge of the coronavirus.

With a push from COVID-19, such “hospital-at-home” programs and other remote technologies — from online visits with doctors to virtual physical therapy to home oxygen monitoring — have been rapidly rolled out and, often, embraced.

As remote visits quickly ramped up, Medicare and many private insurers, which previously had limited telehealth coverage, temporarily relaxed payment rules, allowing what has been an organic experiment to proceed.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime thing,” said Preeti Raghavan, an associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore. “It usually takes a long time — 17 years — for an idea to become accepted and deployed and reimbursed in medical practice.”

Physical therapists traded some hands-on care for video-game-like rehabilitation programs patients can do on home computer screens. And hospitals like Tufts, where Shanoski was a patient, sped up preexisting plans for hospital-at-home initiatives. Doctors and patients were often enthusiastic about the results.

“It’s a great program,” said Shanoski, now fully recovered after 11 days of receiving this care. At home, he could talk with his fiancée “and walk around and be with my dogs.”

But what will remain of these innovations in the post-COVID era is now the million-dollar question. There is a need to assess what is gained — or lost — when a service is delivered remotely. Another variable is whether insurers, which currently reimburse virtual visits at the same rate as if they were in person, will continue to do so. If not, what is a proper amount?

It remains to be seen what types of novel remote care will persist from this born-of-necessity experiment.

Said Glenn Melnick, a health-care economist at the University of Southern California who studies hospital systems: “Pieces of it will, but we have to figure out which ones.”

Hospital At Home

Long established in parts of Australia, England, Italy and Spain, such remote programs for hospital care have not caught on here, in large part because U.S. hospitals make money by filling beds.

Hospital-at-home initiatives are offered to stable patients with common diagnoses — like heart failure, pneumonia and kidney infections — who need hospital services that can now be delivered and managed at a distance.

Patients’ homes are temporarily equipped with the necessities, including monitors and communication equipment as well as backup internet and power sources. Care is overseen by health professionals in remote “command centers.”

Medically Home, the private company providing the service for Tufts, sent its own nurses, paramedics and other employees to handle Shanoski’s daily medical care — such as blood tests or consultations via camera with doctors. They inserted an IV and made sure it was working properly during their visits, which often totaled three a day. Even when Medically Home employees were not there, devices monitored Shanoski’s blood pressure and oxygen levels.

For patients transferred from the hospital, like Shanoski, Tufts pays Medically Home a portion of what the hospital receives in payment. For transfers from an emergency room, Medically Home is paid directly by insurers with which it has contracts.

Before the pandemic, at least 20 U.S. health systems had some form of hospital-at-home setup, said Bruce Leff, a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who has studied such programs. He said that, for the right patients, they’re just as safe as in-hospital care and can cost 20% to 30% less.

Tele-Rehab?

Glenn Shanoski, a 52-year-old electrician, spent 11 days with hospital-level care at home —– offered by Tufts Medical Center in Boston. Tufts provides daily visits from medical teams to closely monitor patients in their homes. (Courtesy of Glenn Shanoski)

When the coronavirus shut down elective procedures, many physical-therapy offices had to close, too. But a number of patients who had recently had surgery or injuries were at a crucial point in recovery.

Therapists scrambled to set up video capability, while their trade association called insurers and regulators to convince them that remote physical therapy should be covered.

At the end of April, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services added remote physical, speech and occupational therapy to the list of medical services it would cover during the pandemic. Just as it had done for other services, the agency said payment would be the same as for an in-person visit.

Though some patient care cannot be done virtually, such as hands-on manipulation of tight muscles, the doctors discovered many advantages: “When you see them in their home, you can see exactly their situation. Rugs lying around on the floor. What hazards are in the environment, what support systems they have,” said Raghavan, the rehabilitation physician at Johns Hopkins. “We can understand their context.”

Using video links, therapists can assess how a patient moves or walks, for example, or demonstrate home exercises. There are also specially designed video-game programs — similar to Nintendo Wii — that utilize motion sensors to help rehabilitation patients improve balance or specific skills.

“Tele-rehab was very much in the research phase and wasn’t deployed on a wide scale,” Raghavan said. Her department now does 9 out of 10 visits remotely, up from zero before March.

Pneumonia Monitoring

Even before the coronavirus emergency, some patients with mild pneumonia were treated as outpatients.

Now, with hospitals busy with COVID-19 cases and patients eager to minimize unneeded exposure, more physicians are considering this option and for sicker patients. The key is using a small device called a pulse oximeter, which clips onto the end of a finger and measures heart rate, while also estimating the proportion of oxygen in the blood. Costing at most a few hundred dollars, and long common in doctors’ offices, clinics and emergency rooms, the tiny machine can be sent home with patients or purchased online.

“We do it on a case-by-case basis,” said Dr. Gary LeRoy, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. It’s a good option for relatively healthy patients but is not appropriate for those with underlying conditions that could lead them to deteriorate rapidly, such as heart or lung disease or diabetes, he said.

A pulse oximeter reading of 95% to 100% is considered normal. Generally, LeRoy tells patients to call his office if their readings fall below 90%, or if they have symptoms like fever, chills, confusion, increasing cough or fatigue and their levels are in the 91-to-94 range. That could signal a deterioration that requires further assessment and possibly hospitalization.

“Having a personal physician involved in the process is critically important because you need to know the nuances” of the patient’s history, he said.

What It All Looks Like In The Future

Virtual therapy requires patients or their caregivers to accept more responsibility for maintaining the treatment regimen, and also for activities like bathing and taking medicines. In return, patients get the convenience of being at home.

But the biggest wild card in whether current innovations persist may be how generously insurers decide to cover them. If insurers decide to reimburse telehealth at far less than an in-person visit, that “will have a huge impact on continued use,” said Mike Seel, vice president of the consulting firm Freed Associates in California. A related issue is whether insurers will allow patients’ primary caregivers to deliver treatment remotely or require outsourcing to a distant telehealth service, which might leave patients feeling less satisfied.

The industry’s lobbying group, America’s Health Insurance Plans, said the ongoing crisis has shown that telehealth works. But it offered no specifics on future reimbursement, other than encouraging insurers to “closely collaborate” with local care providers.

Whether virtual therapy is cost-effective “remains to be seen,” said USC’s Melnick. And it depends on perspective: It may be cheaper for a hospital to do a virtual physical therapy session, but the patient might not see any savings if insurance doesn’t reduce the out-of-pocket cost.

Julie Appleby is a Kaiser Health News reporter.jappleby@kff.org, @Julie_Appleby

Shefali Luthra: How insurers sank plan for 'public option' in Connecticut

Headquarters of the huge insurance company Cigna in Bloomfield, Conn

Health-care costs were rising. People couldn’t afford coverage. So, in Connecticut, state lawmakers took action.

Their solution was to attempt to create a public health insurance option, managed by the state, which would ostensibly serve as a low-cost alternative for people who couldn’t afford private plans.

Immediately, an aggressive industry mobilized to kill the idea. Despite months of lobbying, debate and organizing, the proposal was dead on arrival.

“That bill was met with a steam train of opposition,” recalled state Rep. Sean Scanlon, who chairs the legislature’s insurance and real estate committee.

Through a string of presidential debates, the idea of a public option was championed by moderate Democrats ― such as former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and former Vice President Joe Biden ― as an alternative to a single-payer “Medicare for All” model. Those center-left candidates again touted the idea during the Feb. 25 Democratic debate in South Carolina, with Buttigieg arguing such an approach would deliver universal care without the political baggage. (Buttigieg and Klobuchar have since ended their presidential bids.)

The public option has a common-sense appeal for many Americans who list health-care costs as a top political concern: If the market doesn’t offer patients an affordable health care insurance they like, why not give them the option to buy into a government-run health plan?

But the stunning 2019 defeat of a plan to implement such a policy in Connecticut — a solidly blue, or liberal-leaning, state — shows how difficult it may be to enact even “moderate” solutions that threaten some of America’s most powerful and lucrative industries. The health-insurance industry’s fear: If the average American could weigh a public option — Medicare or Medicaid or some amalgam of the two — against commercial plans on the market, they might find the latter wanting.

That fear has long blocked political action, said Colleen Grogan, a professor at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration, because “insurance companies are at the table” when health care reform legislation gets proposed.

To be sure, the state calculus is different from what a federal one would be. In the statehouse, a single industry can have an outsize influence and legislators are more skittish about job loss. In Connecticut, that was an especially potent force. Cigna and Aetna are among the state’s top 10 employers.

“They became aware of the bill, and they moved immediately to kill it,” said Frances Padilla, who heads the Universal Health Care Foundation of Connecticut and worked to generate support for the public option.

And those strategies have been replicated at the national level as a national coalition of health industry players ramps up lobbying against Democratic proposals. Beyond insurance, health-care systems and hospitals have joined in mobilizing against both public option and single-payer proposals, for fear a government-backed plan would pay far less than the rates of commercial insurance.

Many states are exploring implementing a public option, and once one is successful, others may well follow, opening the door to a federal program.

“State action is always a precursor for federal action,” said Trish Riley, the executive director of the National Academy for State Health Policy. “There’s a long history of that.”

Virginia state delegate Ibraheem Samirah introduced a new public option bill this session. In Colorado, Gov. Jared Polis is spearheading an effort. And Washington state is the furthest along — it approved a public option last year, and the state-offered plan will be available next year.

But in 2019, Connecticut’s legislators were stuck between two diametrically opposed constituencies, both distinctly local.

Health costs had skyrocketed. Across the state, Scanlon said, small-business owners worried that the high price of insurance was squeezing their margins. A state-provided health plan, the logic went, would be highly regulated and offer lower premiums and stable benefits, providing a viable, affordable alternative to businesses and individuals. (It could also pressure private insurance to offer cheaper plans.)

A coalition of state legislators came together around a proposal: Let small businesses and individuals buy into the state employee health benefit plan. Insurers’ response was swift.

Lobbyists from the insurance industry swarmed the Capitol, recalled Kevin Lembo, the state comptroller. “There was a lot of pressure put on the legislature and governor’s office not to do this.”

State ethics filings make it impossible to tease out how much of Aetna and Cigna’s lobbying dollars were spent on the public option legislation specifically. In the 2019-20 period, Aetna spent almost $158,000 in total lobbying: $93,000 lobbying the Statehouse, and $65,000 on the governor’s office. Cigna spent about $157,000: $84,000 went to the legislature, and $73,000 to the executive.

Anthem, another large insurance company, spent almost $147,000 lobbying during that same period — $23,545 to the governor, and $123,045 to the legislature. Padilla recalled that Anthem also made its opposition clear, though it was less vocal than the other companies. (Anthem did not respond to requests for comment.)

A coalition of insurance companies and business trade groups rolled out an online campaign, commissioning reports and promoting op-eds that argued the state proposal would devastate the local economy.

Lawmakers also received scores of similarly worded emails from Cigna and Aetna employees, voicing concern that a public option would eliminate their jobs, according to documents shared with Kaiser Health News. Cigna declined to comment on those emails, and Aetna never responded to requests for comment.

Connecticut’s first public option bill — which would let people directly buy into the publicly run state employee health plan ― flamed out.

So lawmakers put forth a compromise proposal: The state would contract with private plans to administer the government health option, allowing insurance companies to participate in the system.

The night before voting, that too fell apart. Accounts of what happened vary.

Some say Cigna threatened to pull its business out of the state if a public option were implemented. Publicly, Cigna has said it never issued such a threat but made clear that a public option would harm its bottom line. The company would not elaborate when contacted by KHN.

Now, months later, both Scanlon and Lembo said another attempt is in the works, pegged to legislation resembling last year’s compromise bill. But state lawmakers work only from February through early May, which is not a lot of time for a major bill.

Meanwhile, other states are making similar pushes, fighting their own uphill battles.

“It really depends on whether there are other countervailing pressures in the state that allow politicians to be able to go for a public option,” Grogan said.

And, nationally, if a public option appears to gain national traction, Blendon said, insurance companies “are clearly going to battle.”

They’re going to go after every Republican, every moderate Democrat, to try to say that … it’s a backdoor way to have the government take over insurance,” he said.

Still, when President Barack first proposed the idea of a public option as part of the Affordable Care Act, it was put aside as too radical. Less than a decade later, support for the idea ― every Democratic candidate backs either an optional public health plan or Medicare for All ― is stronger than it ever has been.

So strong, Grogan said, that it is hard for people to understand “the true extent” of the resistance that must be overcome to realize such a plan.

But in Connecticut, politicians say they’re up for a new battle in 2020.

“We can’t accept the status quo. … People are literally dying and going bankrupt,” Scanlon said. “A public option at the state level is the leading fight we can be taking.”

Shefali Luthra is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Phil Galewitz: Trump's Medicaid chief mostly wrong on its outcomes, access

“This wouldn’t pass muster in a first-year statistics class.’’

— Benjamin Sommers, health-care economist at Harvard, of Medicare-Medicaid chief’s remarks

The Trump administration’s top Medicaid official has been increasingly critical of the entitlement program she has overseen for three years.

Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, has warned that the federal government and states need to better control spending and improve care to the 70 million people on Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for the low-income population. She supports changes to Medicaid that would give states the option to receive capped annual federal funding for some enrollees instead of open-ended payouts based on enrollment and health costs. This would be a departure from how the program has operated since it began in 1965.

In an early February speech to the American Medical Association, Verma noted how changes are needed because Medicaid is one of the top two biggest expenses for states, and its costs are expected to increase 500% by 2050.

“Yet, for all that spending, health outcomes today on Medicaid are mediocre and many patients have difficulty accessing care,” she said.

Verma’s sharp comments got us wondering if Medicaid recipients were as bad off as she said. So we asked CMS what evidence it has to back up her views.

A CMS spokesperson responded by pointing us to a CMS fact sheet comparing the health status of people on Medicaid to people with private insurance and Medicare. The fact sheet, among other things, showed 43% of Medicaid enrollees report their health as excellent or very good compared with 71% of people with private insurance, 14% on Medicare and 58% who were uninsured.

The spokesperson also pointed to a 2017 report by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), a congressional advisory board, that noted: “Medicaid enrollees have more difficulty than low-income privately insured individuals in finding a doctor who accepts their insurance and making an appointment; Medicaid enrollees also have more difficulty finding a specialist physician who will treat them.”

We opted to look at those issues separately.

What About Health Status?

Several national Medicaid experts said Verma is wrong to use health status as a proxy for whether Medicaid helps improve health for people. That’s because to be eligible for Medicaid, people must fall into a low income bracket, which can impact their health in many ways. For example, they may live in substandard housing or not get proper nutrition and exercise. In addition, lack of transportation or child care responsibilities can hamper their ability to visit doctors.

Benjamin Sommers, a health economist at Harvard University, said Verma’s comparison of the health status of Medicaid recipients against people with Medicare or private insurance is invalid because the populations are so different and face varied health risks. “This wouldn’t pass muster in a first-year statistics class,” he said.

Death rates, for example, are higher among people in the Medicare program than those in private insurance or Medicaid, he said, but that’s not a knock on Medicare. It’s because Medicare primarily covers people 65 and older.

By definition, Medicaid covers the most vulnerable people in the community, from newborns to the disabled and the poor, said Rachel Nuzum, a vice president with the nonpartisan Commonwealth Fund. “The Medicaid population does not look like the privately insured population.”

Joe Antos, a health economist with the conservative American Enterprise Institute, also agreed, saying he is leery of any studies or statements that evaluate Medicaid without adjusting for risk.

For a better mechanism to gauge health outcomes under Medicaid, experts point to dozens of studies that track what happened in states that chose in the past six years to pursue the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion. The health law gave states the option to extend Medicaid to everyone with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, or about $17,600 annually for an individual. Thirty-six states and the District of Columbia have adopted the expansion.

“Most research demonstrates that Medicaid expansion has improved access to care, utilization of services, the affordability of care, and financial security among the low-income population,” concluded the Kaiser Family Foundation in summarizing findings from more than 300 studies. “Studies show improved self-reported health following expansion and an association between expansion and certain positive health outcomes.” (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

Studies found the expansion of Medicaid led to lower mortality rates for people with heart disease and among end-stage renal disease patients initiating dialysis.

Researchers also reported that Medicaid expansion was associated with declines in the length of stay of hospitalized patients. One study found a link between expansion and declines in mechanical ventilation rates among patients hospitalized for various conditions.

Another recent study compared the health characteristics of low-income residents of Texas, which has not expanded Medicaid, and those of Arkansas and Kentucky, which did. It found that new Medicaid enrollees in the latter two states were 41 percentage points more likely to have a usual source of care and 23 percentage points more likely to say they were in excellent health than a comparable group of Texas residents.

Medicaid’s benefits, though, affect far more than the millions of nondisabled adults who gained coverage as a result of the ACA. “Medicaid coverage was associated with a range of positive health behaviors and outcomes, including increased access to care; improved self-reported health status; higher rates of preventive health screenings; lower likelihood of delaying care because of costs; decreased hospital and emergency department utilization; and decreased infant, child, and adult mortality rates,” according to a report issued this month by the nonpartisan Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Children — who make up nearly half of Medicaid enrollees — have also benefited from the coverage, studies find. Some studies report that Medicaid contributes to improved health outcomes, including reductions in avoidable hospitalizations and lower child mortality.

Research shows people on Medicaid are generally happy with the coverage.

A Commonwealth Fund survey found 90% of adults with Medicaid were satisfied or very satisfied with their coverage, a slightly higher percentage than those with employer coverage.

Accessible Care?

The evidence here is less emphatic.

A 2017 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine found 84% of Medicaid recipients felt they were able to get all the medical care they needed in the previous six months. Only 3% said they could not get care because of long wait times or because doctors would not accept their insurance.

Verma cites a 2017 MACPAC report that noted some people on Medicaid have issues accessing care. But that report also noted: “The body of work to date by MACPAC and others shows that Medicaid beneficiaries have much better access to care, and much higher health care utilization, than individuals without insurance, particularly when controlling for socioeconomic characteristics and health status.” It also notes that “Medicaid beneficiaries also fare as well as or better than individuals with private insurance on some access measures.”

The report said people with Medicaid are as likely as those with private insurance to have a usual source of care, a doctor visit each year and certain services such as a Pap test to detect cervical cancer.

“Medicaid is not great coverage, but it does open the door for health access to help people deal with medical problems before they become acute,” Antos said.

On the negative side, the report said Medicaid recipients are more likely than privately insured patients to experience longer waiting times to see a doctor. They also are less likely to receive mammograms, colorectal tests and dental visits than the privately insured.

“Compared to having no insurance at all, having Medicaid improves access to care and improves health,” said Rachel Garfield, a vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “There is pretty strong evidence that Medicaid helps patients get the care they need.”

Our Ruling

Verma said that “health outcomes today on Medicaid are mediocre and many patients have difficulty accessing care.”

Numerous studies show people’s health improves as a result of Medicaid coverage. This includes lower mortality rates, shorter hospital stays and more people likely to get cancer screenings.

While it’s hard to specify what “many patients having difficulty accessing care” means, research does show that Medicaid enrollees generally say they have no trouble accessing care most of the time.

We rate the claim as Mostly False.

Phil Galewitz is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Phil Galewitz: pgalewitz@kff.org, @philgalewitz

Judith Graham: What to do if your home health-care agency ditches you

Craig Holly, of Connecticut, was determined to fight when the home health agency caring for his wife decided to cut off services Jan. 18.

The reason he was given by an agency nurse? His wife was disabled but stable, and Medicare was changing its payment system for home health.

Euphrosyne “Effie” Costas-Holly, 67, has advanced multiple sclerosis. She can’t walk or stand and relies on an overhead lift system to move from room to room in their house.

Effie wasn’t receiving a lot of care: just two visits every week from aides who gave her a bath, and one visit every two weeks from a nurse who evaluated her and changed her suprapubic catheter, a device that drains urine from a tube inserted in the abdomen.

But even that little bit helped. Holly, 71, has a bad back and is responsible for his wife’s needs 24/7. Her urologist didn’t have a lift system in his office and had told the couple it was safer to have Effie’s catheter changed regularly at home.

Holly wasn’t sure what to do. Call his congressman and lodge a complaint? Write a letter to the director of the home health agency owned and operated by Hartford HealthCare Corp., one of the largest health care systems in Connecticut?

Things snapped into focus when Holly attended a late November presentation about Medicare’s home health services by Kathleen Holt, associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy.

If you’re told Medicare’s home health benefits have changed, don’t believe it: Coverage rules haven’t been altered and people are still entitled to the same types of services, Holt told the group. (For a complete description of Medicare’s home health benefit, click here.)

All that has changed is how Medicare pays agencies under a new system known as the Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM). This system applies to home health services for older adults with original Medicare. Managed-care-style Medicare Advantage plans, which serve about one-third of Medicare beneficiaries, have their own rules.

Under PDGM, agencies are paid higher rates for patients who need complex nursing care and less for people with long-term chronic conditions who need physical, occupational or speech therapy.

Holly got lucky. When he reached out to Holt, she suggested points to bring up with the agency. Tell them your wife’s urologist wasn’t consulted about a possible discharge from home health, doesn’t agree with this move and is willing to recertify Effie for ongoing home health services, Holt advised.

Within hours, the agency reversed its decision and said Effie’s services would remain in place.

A Hartford HealthCare spokesman said he couldn’t comment on the situation, citing privacy laws. “Our goal is to continue to provide the right care at the right place at the right time with the orders reflecting the specific treatment goals and medical needs of each patient,” he wrote in an email.

“No patients have had services reduced as a result of Medicare’s implementation of the PDGM program.”

But therapists, home health agencies and association leaders say that patients across the country are being told they no longer qualify for certain services (such as vitamin B12 injections or suprapubic catheter changes) or that services have to be cut back or discontinued.

What should you do if this happens to you? Experts have several suggestions:

Get as much information as possible. If your agency says you no longer need services, ask your nurse or therapist what criteria you no longer meet, said Jason Falvey, a physical therapist and postdoctoral research fellow in the geriatrics division at Yale School of Medicine, in New Haven.

Does the agency think skilled services are no longer necessary and that a family member can now provide all needed care? Does it believe the person receiving care is no longer homebound? (To receive Medicare home health services, a person must be homebound and in need of intermittent skilled nursing or therapy services.)

“If the therapist or the agency says that Medicare doesn’t cover a particular service any longer, that should raise red flags because Medicare hasn’t changed its benefits or clinical criteria for home health coverage,” Falvey said.

Enlist your doctor’s help. Armed with this information, get in touch with the physician who ordered home health services for you.

“Your physician should be aware if you feel you’re not getting the services you need,” said Kara Gainer, director of regulatory affairs for the American Physical Therapy Association.

“Doctors should not be sitting on the sidelines; they should be advocating for their patients,” said William Dombi, president of the National Association for Home Care and Hospice.

Take it up the chain of command. Meanwhile, let people at the home health agency know that you’re contesting any decision to reduce or terminate services.

When someone begins home health services, an agency is required to give them a sheet, known as the “Patient Bill of Rights,” with the names and phone numbers of people who can be contacted if difficulties arise. Contact the agency’s clinical supervisor, who should be listed here.

“Call us and trigger a conversation,” said Bud Langham, chief strategy and innovation officer at Encompass Health, which provides home health services to 45,000 patients in 33 states.

Also, contact the organization in your state that oversees home health agencies and let them know you believe your agency isn’t following Medicare’s rules, said Sharmila Sandhu, vice president of regulatory affairs for the American Occupational Therapy Association. This should be among the numbers listed on the bills of rights sheet.

Contact Medicare’s ombudsman. Unlike nursing homes, home health agencies don’t have designated long-term ombudsmen who represent patients’ interests. But you can contact 1-800-Medicare and ask a representative to submit an inquiry or complaint to the general Medicare ombudsman, a spokesman for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said. The ombudsman is tasked with looking into disputes brought to its attention.

File an expedited appeal. If a home health agency plans to discontinue services altogether, staff are required to give you a “Notice of Medicare non-coverage” stating the date on which services will end, the reason for termination and how to file a “fast appeal.” (This notice must be delivered at least two days before services are due to end.) You have to request an expedited appeal by noon of the day after you receive this notice.

A Medicare Quality Improvement Organization will handle the appeal, review your medical information and generally get back to you within three days. In the meantime, your home health agency is obligated to continue providing services.

Shop around. Multiple home health agencies operate in many areas. Some may be for-profit, others not-for-profit.

“All home health agencies are not alike” and if one agency isn’t meeting your needs “consider shopping around,” Dombi said. While this may not be possible in smaller towns or rural areas, in urban areas many choices are typically available.

Contact an advocate. The Center for Medicare Advocacy has been hearing from patients who are being given all kinds of misinformation related to Medicare’s new home health payment system.

Among the things that patients have been told, mistakenly: “Medicare ‘closed a loophole’ as of Jan. 1 so your care will no longer be provided after mid-January,” “Medicare will no longer pay for more than one home health aide per week,” and “We aren’t paid sufficiently to continue your care,” said Judith Stein, the center’s executive director.

Some agencies may not understand the changes that Medicare is implementing; confusion is widespread. Advocates such as the Center for Medicare Advocacy (contact them at here) or the Medicare Rights Center (national help line: 800-333-4114) can help you understand what’s going on and potentially intervene on your behalf.

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

Patty Wright: Newly blue Maine expands access to abortion

The Maine State House, designed by Charles Bulfinch, and built 1829–1832. Bullfinch also designed the famous Massachusetts State House, with its iconic gold dome.

While abortion bans in Republican-led states dominated headlines in recent weeks, a handful of other states have expanded abortion access. Maine joined those ranks in June with two new laws ― one requires all insurance and Medicaid to cover the procedure and the other allows physician assistants and nurses with advanced training to perform it.

With these laws, Maine joins New York, Illinois, Rhode Island and Vermont as states that are trying to shore up the right to abortion in advance of an expected U.S. Supreme Court challenge. What sets Maine apart is how recently Democrats have taken power in the state.

“Elections matter,” said Nicole Clegg of Planned Parenthood of Northern New England. Since the 2018 elections, Maine has its largest contingent of female lawmakers, with 71 women serving in both chambers. “We saw an overwhelming majority of elected officials who support reproductive rights and access to reproductive health care.”

The dramatic political change also saw Maine elect its first female governor, Janet Mills, a Democrat who took over from Paul LePage, a Tea Party stalwart who served two terms. LePage had blocked Medicaid expansion in the state even after voters approved it in a referendum.

Clegg and other supporters of abortion rights hailed the new abortion legislation: “It will be the single most important event since Roe versus Wadein the state of Maine.”

Taken together, the intent of the two laws is to make it easier for women to afford and to find abortion care in the largely rural state.

Nurse practitioners like Julie Jenkins, who works in a small coastal town, said that increasing the number of abortion providers will make it easier for patients who now have to travel long distances in Maine to have a doctor perform the procedure.

“Five hours to get to a provider and back ― that’s not unheard of,” Jenkins said.

Physician assistants and nurses with advanced training will be able to perform a surgical form of the procedure known as an aspiration abortion. These clinicians already are allowed to use the same technique in other circumstances, such as when a woman has a miscarriage.

Maine’s other new law, set to be implemented early next year, requires all insurance plans ― including Medicaid ― to cover abortions. Kate Brogan of Maine Family Planning said it’s a workaround for a U.S. law known as the Hyde Amendment that prohibits federal funding for abortions except to save the life of the woman, or if the pregnancy arises from incest or rape.

“[Hyde] is a policy decision that we think coerces women into continuing pregnancies that they don’t want to continue,” Brogan said. “Because if you continue your pregnancy, Medicaid will cover it. But if you want to end your pregnancy, you have to come up with the money [to pay for an abortion].”

State dollars will now fund abortions under Maine’s Medicaid, which is funded by both state and federal tax dollars.

Though the bill passed in the Democratic-controlled legislature, it faced staunch opposition from Republicans during floor debates including Sen. Lisa Keim.

“Maine people should not be forced to have their hard-earned tax dollars [used] to take the life of a living pre-born child,” said Keim.

Instead, Keim argued, abortions for low-income women should be funded by supporters who wish to donate money; otherwise, the religious convictions of abortion opponents are at risk. “Our decision today cannot be to strip the religious liberty of Maine people through taxation,” Keim said during the debate.

Rep. Beth O’Connor, a Republican who says she personally opposes abortion but believes women should have a choice, said she had safety concerns about letting clinicians who are not doctors provide abortions.

“I think this is very risky, and I think it puts the woman’s health at risk,” O’Connor said.

In contrast, advanced practice clinicians say the legislation, which will take effect in September, said this law merely allows them to operate to the full scope of their expertise and expands access to important health care. The measure has the backing of physician groups like the Maine Medical Association.

Just as red-state laws restricting abortion are being challenged, so are Maine’s new laws. Days after Maine’s law on Medicaid abortion passed, organizations that oppose abortion rights announced they’re mounting an effort to put the issue on the ballot for a people’s veto.

This story is part of a partnership that includes Maine Public Radio, NPR and Kaiser Health News. Patty Wright is a reporter at Maine Public Radio.

Nicole Braun: The GOP's war on democracy in the Heartland

From OtherWords.org

For millions of Americans, there’s no “making it” if you fall beneath a certain social class line. And the Michigan GOP, which was roundly rejected in the last election, is determined to keep it that way.

In neighboring Wisconsin, Republicans decided to show voters there that their voices, votes, hardships, and pain don’t matter. They passed a series of lame-duck bills making it all but impossible for newly elected Democrats to implement their agenda.

Here in Michigan, the GOP quickly followed suit. Republicans pushed many bills through the legislature in their last days in office that hurt regular folks but benefit the elite, despite election results that show unambiguously what voters want.

Among many other things, these egregious bills ignore voter-approved sick leave protections and minimize wage increases, make it more difficult to vote, restrict campaign finance reform measures, and — for good measure — make it harder for voters to get future proposals on the ballot.

The GOP doesn’t care how tough many folks in Michigan have it, and there’s no apparent logic to their thinking except to make it tougher.

For instance, earlier Medicaid rules passed by Michigan Republicans say that folks need to work 20 hours a week. But often when you work 20 hours a week, you no longer qualify for Medicaid — even if you still can’t afford private insurance.

And when you work 20 hours a week without insurance and get sick, you’re out of luck — because Republicans just gutted a citizen-passed initiative to make sure workers have paid sick leave.

They also pushed forward a bill to drastically slow down minimum wage increases approved by voters. Studies show that no one in America can afford a two-bedroom apartment anywhere working even full-time for minimum wage, but Republicans watered down the voter-approved increase anyway.

Outgoing Republican Gov. Rick Snyder signed those bills. Sadly, many folks I talked to weren’t surprised.

Folks in Michigan have been suffering for years under GOP rule. We’ve seen blatant power abuses, including the undemocratic recall of elected officials. We’ve seen rising inequality, a rampant opioid crisis, poverty, corruption, and egregious failures like the Flint water crisis.

“Our governor has a body count — the kids he killed in Flint,” said Wil Gallivan, who lives outside Flint.

“Expecting him to all of a sudden gain some decency is just wishful thinking. We should all be wearing yellow vests at the Capitol, 100,000 people strong,” he added, referring to the “yellow vest” protests rocking France. “But who can afford to take time off their jobs to do that?”

Recalling Snyder’s purchase of an exorbitantly expensive cake just as news of the Flint water crisis was breaking, former bartender and Flint native Carol Frey reflected: “People who pull that usually lack the compassion and empathy chip.”

I teach sociology. It’s a given that the more inequality there is, the more violence, anger, despair, addiction, and hatred there is too. Inequality produces unhealthy humans and unhappy communities. No one can bloom in such unhealthiness.

By pushing forward these harmful bills even after a progressive wave, Michigan Republicans are saying that the people who voted them out don’t matter. So are their neighbors in Wisconsin and in other states across the country (like Florida, where lawmakers are trying to water down a voter-passed initiative to give people who serve time their vote back).

Still, more protests and acts of resistance are planned. Michigan people are strong, and we fight back — even if we’re broke and tired.

Nicole Braun is a sociologist in northern Michigan.

Peter Certo: GOP's mid-terms campaign depended on lies, fear-mongering and rule-rigging

This 1874 cartoon by Thomas Nast is considered the first important portrayal of the Republican elephant.

Via OtherWords.org

I can’t be the only one who spent the night of the mid-terms tossing and turning. Though I managed to shut off the coverage and try to sleep, spasms of anxiety woke me repeatedly throughout the dreary hours.