James P. Freeman: Department stores in fast descent as Amazon takes their business and destroys jobs

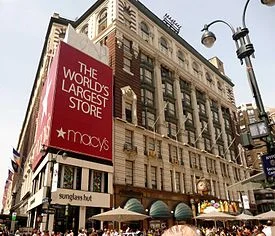

Macy's flagship store in Manhattan.

“Macy’s of today is like in soul and spirit to

Macy’s of yesterday; Macy’s of tomorrow…”

— Edward Hungerford, The Romance of a Great Store (1922)

If today is yesterday’s tomorrow, the Macy’s of 2017 would be unrecognizable to its founder, Rowland Hussey Macy. Except, perhaps, for the ubiquitous red star, the company’s logo, which was inked onto his forearm as a young sailor, while working on the whaling ship Emily Morgan, based out of New Bedford, Mass.. The star was inspired by the North Star, which, according to legend, guided him to port and an optimistic future. Today, the company — and, by extension, the traditional retailing industry — rocked by an exceptional gale, looks to the heavens for safe harbor and secure future. The turbulence, however, is a healthy sign of the creative destruction of capitalism. Accordingly, let traditional retail perish.

Last April, a New York Times expose, “Is American Retail at a Historic Tipping Point?,” revealed that 89,000 Americans have been laid off in general-merchandise stores since October 2016. “That is more than all of the people employed in the United States coal industry, which President Trump championed during the campaign as a prime example of the workers who have been left behind in the economic recovery.”

About one out of every 10 Americans works in retail. That’s nearly 16 million people (both online and in stores), confirms the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. Unsurprisingly, only 5 percent are represented by unions.

More than 300 retailers have filed for bankruptcy just in 2017. Among them: Gymboree (operating 1,300 stores), rue21 (1,200 stores), Payless ShoeSource (4,400 stores), The Limited (250 stores), and a century-old regional department store company, Gordmans Stores (106 stores, in 22 states). In the past year, Macy’s has announced it would close 100 stores (identifying 68 locations, eliminating 10,000 jobs). J.C. Penney will close 138 stores. Sears (which also owns Kmart) is shuttering 150 stores and said last March that the company has “substantial doubt” about its survival after 13 decades in business. Since 2010, Sears has lost $10.4 billion and has closed several hundred stores.

A report released this spring by Credit Suisse, the financial-services firm, estimates that 8,640 retail stores will close by year’s end and, more staggering, approximately one quarter of the nation’s 1,100 malls will close in the next five years.

“Modern-day retail is becoming unrecognizable from the glory era of the department store in the years after World War II,” notes the Times. “In that period, newly built highways shuttling people to and from the suburbs eventually gave rise to shopping malls — big, convenient, climate-controlled monuments to consumerism with lots of parking.” The glitz and glamour of shopping reminiscent of the Mad Men period is over. Instead, a wrenching, permanent restructuring is likely under way. As it should be.

What happened?

Shifting consumer shopping habits driven by, and probably, a result of, e-commerce. Stated simply: “market forces.” A concept understood by ordinary people. Alarmingly, though, highly compensated retail executives were slow in identifying these new dynamics. For which many big retailers are now desperately, but not adequately, adapting to these changes. They are failing.

Devoid of any romance, today’s retail is a hard scrabble of Sisyphean drudgery. Product comes in. Product goes out. Product comes back in … Repeat. Generic and dingy department stores are full of tired-looking mannequins and haggard-looking, underpaid sales associates pushing promotions and credit cards. But many stores are empty of customers.

America is called “overstored” — having too much retail space, which now totals about 7.3 square feet per capita. On a comparative basis, that is well above the 1.7 square feet per-capita in Japan and France, and the 1.3 square feet in the United Kingdom. Jonathan Berr of Moneywatch says: “Overstoring can be traced back to the 1990s when the likes of Walmart, Kohls, Gap, and Target were expanding rapidly and opening new divisions.” And then the Internet happened.

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw the evolution of a new business model. Those who embraced a so-called “brick and click” model (combining brick-and-mortar operations with online presence) were certain to survive, and those who executed it well would likely thrive for the foreseeable future. Many retailers were late to the party. When they did arrive, they never harmonized their physical space and cyberspace. Consequently, traditional retailers never kept pace with the value created by the likes of Amazon. The new disruptors perfected the model and, more importantly, created a better customer experience.

Between 2010 and 2014, e-commerce grew by an average of $30 billion annually. Now, e-commerce represents 8.5 percent of all retail sales, (trending straight upward since 2000) disproportionately affecting the big-box retailers that are anchor tenants in malls that, in turn, draw foot traffic from which other mall retailers ultimately benefit. ShopperTrak estimates that retail store foot traffic has plunged 57 percent between 2010 and 2015. And more stunning, Amazon is expected to surpass Macy’s this year to become the biggest apparel seller in the United States.

Macy’s, self-described as “America’s Department Store” — a brand celebrating ubiquity over uniqueness — is symbolic and symptomatic of retail’s quandary.

With its corporate sibling, Bloomingdale’s, the company is a constellation of complexities. Far from its meager beginnings as a single dry goods store in Haverhill, Mass. when it opened in 1851, it is now a cobbled-together conglomerate operating 700 stores in 45 states, employing 140,000 (of which 10 percent are unionized). Because of so many mergers and acquisitions, there is no unifying culture. It has 50 million proprietary charge accounts on record (nearly one in six Americans).

Macy's flagship store in Herald Square in Manhattan attracts 23 million visitors annually. Known as an “omnichannel retailer” (myriad ways of consumer engagement; i.e., store, Internet, mobile device), with sales over $25.7 billion, Macy’s is still profitable (earning $619 million last year). But it is in trouble.

In July 2015, Macy’s market capitalization (total value of its publicly traded shares) was more than $22 billion. It has plummeted to about $7 billion today. Constantly tweaking marketing and merchandising, the company nevertheless reported that net sales declined for the ninth straight quarter, in May. Saddled with $6.725 billion in debt and with fewer customers, over half its earnings are derived from its credit-card business. (Just three years ago, credit cards accounted for a quarter of its earnings.) Lead times for its lifeblood, the supply chain, are long and slow. Real estate holdings (estimated to be worth between $15 billion and $20 billion) are substantially more valuable than its business operations. Double-digit growth in online business is cannibalizing negative growth in store business.

Macy’s is ever-reliant upon the next generation of shoppers, but Millennials may not be that reliable; they defy consumption patterns that previous generations followed for years (less materialistic and more loyal to experiences than to physical brands). And Amazon’s new Prime Wardrobe might prove to be a death star, obliterating many red ones. Gloomy and overwhelmed, Macy’s reflects the industry at large.

This past January, Amazon announced it would create 100,000 jobs over the course of 18 months. Yet it is foolish to think that Amazon — which is much more efficient than traditional retailers — will absorb all the displaced workers.

As Rex Nutting, writing for MarketWatch, warns, what Amazon “won’t tell us is that every job created at Amazon destroys one or two or three others.” And what Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos “doesn’t want you to know is that Amazon is going to destroy more American jobs than China ever did.”

Even if the American consumer is the beneficiary of these disruptive but necessary market forces, sooner or later this economic issue will become a political issue.

Conservative commentator George Will raises a good question: “Why should manufacturing jobs lost to foreign competition be privileged by protectionist policies in ways that jobs lost to domestic competition are not?”

President Trump should, but probably won’t, answer a question that would help clarify the puzzling public policy he is now crafting (see his “major border tax” proposals). As the president will surely learn, economics — like health care — is complicated fare. And like most things involving Trump, it is personal.

During last year’s presidential campaign, Trump said Amazon has “a huge antitrust problem.” (An analysis found that 43 percent of all online retail sales in the United States went through Amazon in 2016.) Notably, Bezos owns The Washington Post, largely critical of the president. In late 2015, Trump called for a boycott of Macy’s after the company stopped selling Trump merchandise and severed ties with the presidential candidate because of comments he made about Mexicans earlier that year.

Then there is his daughter, Ivanka Trump. Despite her father’s call last January that “We will follow two simple rules — buy American and hire American,” she still owns an apparel company with much of its product line foreign-made. And with gilded irony, some is still sold at Macy’s.

With or without first family entanglements, markets will dictate those retailers it deems omnipresent and obsolescent.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer and former columnist with The Cape Cod Times. He formerly worked in financial services.