Llewellyn King: Great newspaper editors I’ve known

Martin Baron, who servved as head editor of The Miami Herald, The Boston Globe and The Washington Post. He lead The Globe’s investigation of sexual abuse of young people by Catholic priests, an investigation dramatized in the Academy Awards-winning movie Spotlight.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I am something of a connoisseur of editors. I have worked for them, alongside them, and have hated and admired them.

So I was ecstatic when Adam Clayton Powell III, my cop-host on the TV show White House Chronicle, told me he contacted Martin “Marty” Baron, who has a place in the pantheon of great editors, and he agreed to come on the show.

We recorded a two-part series with Baron, which was a tour de force appearance. He talked about the excitement of being the editor of The Miami Herald when Elian Gonzalez was the big story; the years-long unveiling of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church in The Boston Globe when he was its editor; and his becoming executive editor of The Washington Post and its transition from being a family property to being owned by Jeff Bezos, then the world’s richest man.

As he did in his book, Collision of Power: Trump, Bezos, and The Washington Post, he discussed how Trump early on had the new Post team to dinner at the White House and endeavored to co-opt them into the Trump camp. Trump had, as Baron explained, picked on the wrong team.

Baron’s biggest achievement, I believe, was the investigation that exposed the Catholic Church. I was traveling frequently to Ireland at that time — a country, sadly, that had seen more than its share of clerical excess. The Globe’s revelations had an immediate impact there and around the world: Think of the thousands of boys and girls who won’t be abused as a result.

Every editor edits differently and leaves a different mark. I worked for a weekly newspaper editor in Zimbabwe, Costa Theo, who set much of the hot type and edited on the Linotype machine. He urged me to use what he called “informants” many years before Watergate ushered in the practice of talking about “sources” without naming them and relying on the integrity of the reporter to guarantee the existence of the sources.

Herbert Gunn, father of the poet Thom Gunn, edited various newspapers in London’s Fleet Street — when I knew him, it was The Sunday Dispatch. He sat in a commanding way on what was called the “backbench” at the end of the newsroom and edited what he thought needed his touch in green ink with a Parker 51. If you saw green ink, you jumped.

Gunn was a superb editor and, like Ben Bradlee at The Post, gave a theatrical performance as well. All I ever saw in green ink were cryptic notes like “15 minutes.” That meant, “I will see you in the pub in 15 minutes.” It was an assignment not an invitation.

Some editors are technicians and change the look of the papers they edit. John Denson, at The New York Herald Tribune, is credited with introducing horizontal layouts using Bodoni typefaces as the principal type of the newspaper. This became the standard for many U.S. newspapers, including The Washington Post.

A newspaper genius, David Laventhol, put the women’s page in The Post to flight. As the Style section’s first editor, he did it with typological aplomb and with the use of photos in a Life magazine way: big and bold.

Laventhol, who ended up as publisher of the Los Angeles Times and Newsday, came to The Post from The New York Herald Tribune, where he had risen to managing editor. He and I worked together briefly in 1963 and I remember him having a days-long battle with Marguerite Higgins, the famous foreign correspondent, over the use of the word “exotic.”

Of course, Laventhol was only able to create the revolutionary Style section because executive editor Bradlee gave him free rein.

Bradlee edited with leadership, while affecting a kind international jewel thief persona, as might be played by David Niven or Steve McQueen. His genius always was the big picture. He didn’t write headlines or change captions, but he did decide the big stories of the day.

One of those stories was about a break-in at an office and apartment complex called The Watergate. I had arranged a dinner date with a reporter at the rival Evening Star. She called me and said, “I am afraid I will be late. There has been some sort of break-in at The Watergate. But it can’t be important because the Post is sending Carl.”

At that time, Carl Bernstein wasn’t a star, just a young city-desk reporter. I don’t think my date that night stayed in journalism.

Baron, like Bradlee, had a nose for the big one — and he brought it home.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: AI’s assault on journalism and many other jobs will intensify

AI robot at Heinz Nixdorf Museum, in Paderborn, Austria

—- Photo by Sergei Magel/HNF

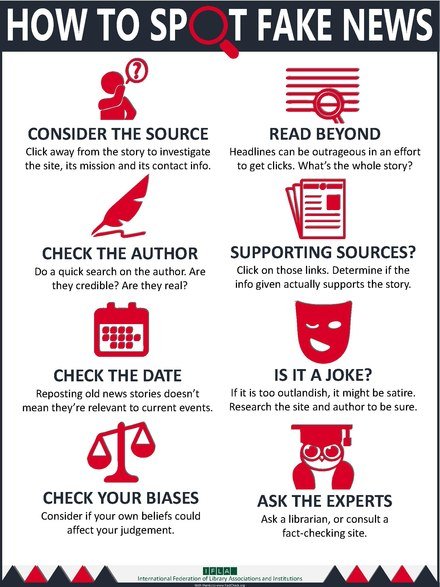

Infographic published by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions.

This article is based on remarks the author made to the Association of European Journalists annual congress in Vlore, Albania, last month.

I am a journalist. That means, as it was once explained to me by Dan Raviv, of CBS News, that I try to find out what is going on and tell people. I know no better description than that of the work.

To my mind, there are two kinds of news stories: day-to-day stories and those that stay with us for a long time.

My long-term story has been energy. I started covering it in 1970, and, all these years later, it is still the big story.

Now, that story for me has been joined by another story of huge consequence to all of us, as energy has been since the 1970s. That story is artificial intelligence.

Leon Trotsky is believed to have said, “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.” I say, “You may not be interested in AI, but AI is interested in you.”

Just as the Arab oil embargo of October 1973 upended everything, AI is set to upend everything going forward.

The first impact on journalism will be to truth. With pervasive disinformation, especially emanating from Russia, establishing the veracity of what we read — documents we review, emails we receive — will be harder. The provenance of information will become more difficult to establish.

Then, it is likely that there will be structural changes to our craft. Much of the more routine work will be done by AI — such things as recording sports results and sifting through legal documents. And, if we aren’t careful, AI will be writing stories.

One of the many professors I have interviewed while reporting the AI story is Stuart Russell, at the University of California at Berkeley, who said the first impact will be on “language in and language out.” That means journalism and writing in general, law and lawyering, and education. The written word is vulnerable to being annexed by AI.

The biggest impact on society is going to be on service jobs. The only safe place for employment may be artisan jobs — carpenters, plumbers and electricians.

Already, fast-food chains are looking to eliminate order-takers and cashiers. People not needed, alas.

The AI industry — there is one, and it is growing exponentially —likes to look to automation and say, “But automation added jobs.”

Well, all the evidence is that AI will subtract jobs almost across the board. Think of all the people around the world who work in customer service. Most of that will be done in the future by AI.

When you call the bank, the insurance agency, or the department store, a polite non-person will be helping you. Probably, the help will be more efficient, but it will represent the elimination of all those human beings, often in other countries, who took your orders, checked on your account, helped you decide between options of service, and to whom you reported your problems or, as often, voiced your anger and disappointment.

The AI bot will cluck sympathetically and say something like, “I am sorry to hear that. I will help you if I can, but I must warn you that company policy doesn’t allow for refunds.”

On the upside, research — especially medical research — will be boosted as never before. One researcher told me a baby born today can expect to live to 120 — another big story.

As journalists, we are going to have to continue to find out what is going on and tell people. But we will also have to find new ways of watermarking the truth. Leica, for instance, has come out with a camera that it says can authenticate the place and time that a photo was taken.

We are going to have to find new outlets for our work where people will know that it was written and reported by a human being, one of us, not an algorithm.

Journalists are criticized constantly for our failings, for allegedly being left or right politically, for ignoring or overstating, but when war breaks out, we become heroes.

I salute those brave colleagues reporting from Gaza and Ukraine. They are doing the vital work of finding out what is going on and telling us. Seventeen have been killed in Ukraine and 34 in Gaza. They are the noble of our trade.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Resilience is the key word now as utilities face increasing stresses

Regional transmission organizations in the continental U.S.

— Graphic by BlckAssn

WEST WARWICK

We all know that sinking feeling when the lights flicker and go out. If bad weather has been forecast, the utility has probably sent you advance warning that there could be outages. You should have a flashlight or two handy, fuel the car, charge your cell phone and other electronic devices, take a shower, and fill all the containers you can with water. If it is winter, put extra blankets on beds and pray that the power stays on.

Disaster struck mid-February in Texas. Uri, a freak and deadly winter storm, froze the state’s power grid. It lasted an unusually long time: five terrible days.

There was chaos in Texas, including more than 150 deaths. The suffering was severe. Paula Gold-Williams, president and CEO of San Antonio-based CPS Energy, told a recent United States Energy Association (USEA) press briefing on resilience that the deep freeze was an equal opportunity disabler: Every generating source was affected. “There were no villains,” she said.

Uri wasn’t just a Texas tragedy, but also a sharp warning to the electric utility industry across the country to look to their preparedness, and to take steps to mitigate damage from cyberattacks and aberrant, extreme weather.

This is known as resilience. It is the North Star of gas and electric utility companies. They all have resilience as their goal.

But it is an elusive one, hard to quantify and one that is, by its nature, always a moving target.

This industry-wide struggle to improve resilience comes at a time when three forces are colliding, all of them impacting the electric utilities: more extreme weather; sophisticated, malicious cyberattacks; and new demands for electricity.

On the latter rests the future of smart cities, electrified transportation, autonomous vehicles, delivery drones, and even electric air taxis. The coming automation of everything -- from robotic hospital beds to data mining -- assumes a steady and uninterrupted supply of electricity.

The modern world is electric and modern cataclysm is electric failure.

Richard Mroz, a past president of the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities, who had to deal with the havoc of Superstorm Sandy in 2012, said at the USEA press briefing, “All our expectations about our critical infrastructure, particularly our electric grid, have increased over time. We expect much more of it.”

Gold-Williams said extreme cold and extreme heat, as in Texas this year, put special pressures on the system. She said the future is a partnership with customers, and that they must understand that there are costs associated with upgrading the system and improving resilience. Currently, CPS Energy is implementing post-Uri changes, she said.

Joseph Fiksel, professor emeritus of systems engineering at Ohio State University, said at the USEA briefing that the U.S. electric system “performs at an extraordinary level of capacity” compared to other parts of the world. He said utilities must rethink how they design their systems to recognize the huge number of calamities around the world that have affected the industry.

A keen observer of the electric utility world, Morgan O’Brien, executive chairman of Anterix, a company that is helping utilities move to private broadband networks, believes communications are the vital link. He told me, “Resilience for utilities is the time in which and the means by which service is restored after ‘bad things’ happen, be they weather events of malicious meddling. Low-cost and ubiquitous sensors connected by wireless broadband technologies, are the instruments of resiliency for the modern grid. No network is so robust that failure is impossible, but a network enabled by broadband conductivity uses technology to measure the occurrence of damage and to speed the restoration of service.”

Neighborhood microgrids, fast and durable communications, diversity of generation, undergrounding critical lines, storage and cyber alertness are part of the resilience-seeking future.

As more is asked of electricity, resilience becomes a byword for keeping the fabric of the modern world intact. Or at least repairing it fast when it tears.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington,D.C.

--

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Thanks!

Got it.

Done.

ReplyReply allForward