John O. Harney: The Rose Kennedy Greenway bursts into bloom

The Rose Kennedy Greenway

Some sights on the Greenway:

BOSTON

I began volunteering as a phenologist on the Rose Kennedy Greenway, in downtown Boston, in spring 2023 and returned a few weeks ago for the 2024 season.

Peppermint-striped tulips were flowering along Pearl Street. Grape hyacinths create purple blankets; anemones whitish carpets. Hellebores that made an early spring show with dusty green-white and pink flowers were already fading. In one spot, it looked like a resting animal has flattened a bed of irises and allium.

Last year, all narcissuses were daffodils to my hardly trained eye. This year, I think I was seeing poeticus with white petals and yellow and reddish-outlined centers, sagitta with yellow double flowers around an orange tube and pheasants eye with its complex yellow and orange center. But I could be wrong.

Many plants were leafing but not yet flowering: irises, alliums, yellow- and red-twig dogwoods, lamb’s ear, roses, penstemon leafing purplish, dracunculus, astilbes, peonies, tickseed in a tough place along Purchase Street, nepeta, grasses near the tunnel vent still yellowish but with a few strands of green, achillea, aruncus and hosta shoots I’ve watched turn from young purplish shoots to fat green leaves reminiscent of a Rousseau painting. Few veggies or fruits visible. No sunflowers yet.

(By the way, in my old job as the executive editor of the New England Journal of Higher Education I was in charge of editorial style rules … things such as when to capitalize words, including names of plants I suppose. It always seemed too arbitrary, and, in retirement, I don’t bother.)

At the corner of Congress Street, I notices a mat of creeping blue phlox with its many light blue-purplish flowers—not, to my eye at least, the pink phlox associated with April 2024’s pink moon.

Speaking of such connections, serviceberry shrubs (also known as shadbushes) had flowered, mirroring the season when shad fish run up New England rivers and, for me, the promise of the delicious season of shad roe.

Jumping out to me on Parcel 21 was a humble dandelion. I note that, sure, it’s a pest, but it’s flowering full yellow, so it gets a 3 in the Greenway ranking system that I’ve never quite got my head around, as they say. The “best” rank among 1 to 5 is 3, not the lowest or highest, but 3 for full flower … peak.

A few other observations …

Maybe it’s the natural magnificence of the Greenway that somehow makes man-made signs catch my eye. Even the troubles of the world pierce the serenity of the park. Take the spot near the North End where a Priority Mail sticker on a park sign reads: “FROM: POWER TO THE RESISTANCE TO: GLOBALIZE THE INTIFADA’’.

Then the welcome reminder of “No mow May on the Greenway … The Greenway Conservancy is participating in Plantlife’s No Mow May initiative to support local pollinators, reduce lawn inputs, and grow healthier lawns. Certain areas of the Greenway will not be mowed in May.” A noble goal for homeowners too.

Nice to see a rare nametag on the Greenway identifying the good-looking and great-smelling Koreanspice viburnum. I had proposed such tagging last year in my piece on A Volunteer Life. Undoubtedly, others made similar suggestions. Still, I naively congratulated myself for any role in the tag, as two houseless people tried to tell me that there are apps on the market that ID plants. Immersed in my headphones, I reacted dismissively. Like a jerk, really. Quickly realizing my rudeness, I returned and apologized. These gardens are theirs more than mine.

With the helpful tips from the houseless on my mind and my interest in signs piqued, I also noticed for the first time, in Parcel 22, a green sign reading: “PARK CLOSED, 11 PM – 7 AM Trespassers will be prosecuted.”

With its tunnel vent, Parcel 22 is a big part of my Greenway life partly for its proximity to the park’s edible and pollinator gardens and Dewey Square and the Red Line plaza. The tunnel vent holds the Greenway mural. A sign reads: “What has this mural meant to you?” A mailbox is supplied for reader comments. One of the recent murals depicted a youth from the city, who critics insisted was a Middle Eastern terrorist. (Murals are dangerous business in New England. See here and here.)

And now to presumably dazzle the Greenway: colorful coneflowers, sturdy Joe Pye weeds, beebalm, furry salvia, white fringe trees, flowering black elderberries and hydangeas.

John O. Harney: Remembering my brother; ‘safe for blueberrying’

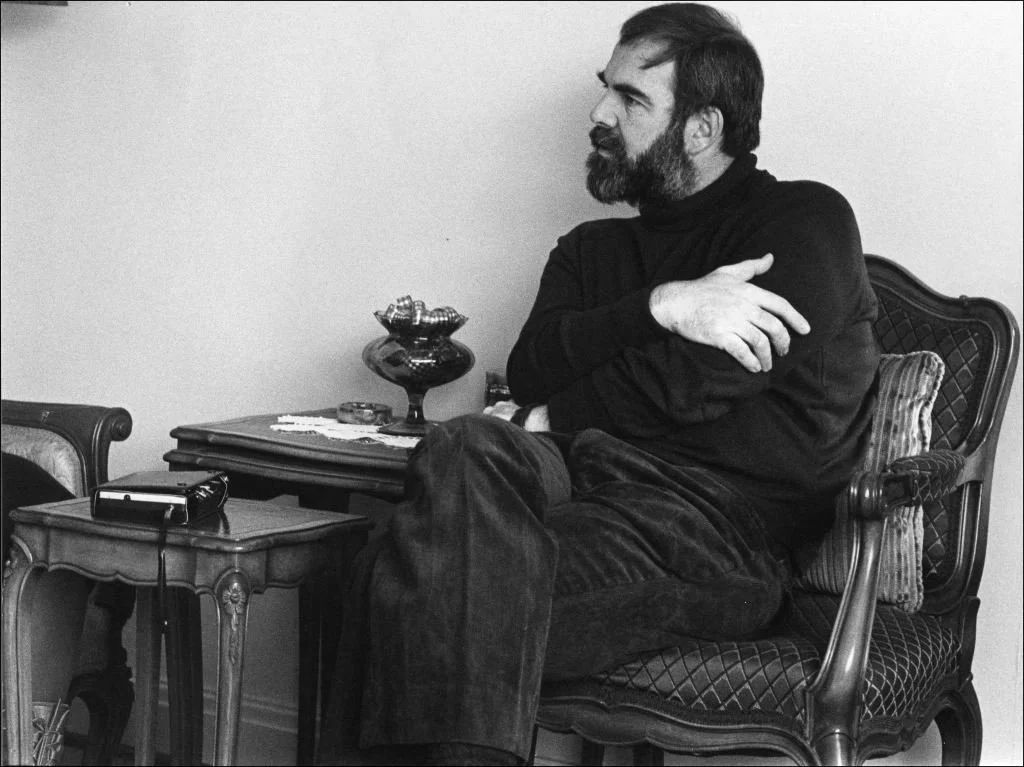

Robert Harney

My oldest brother Robert, historian, social observer and role model, died nearly 35 years ago after an unsuccessful heart transplant. One doctor quipped that there was not a heart big enough to replace Bob’s.

Memories of my childhood feature Bob’s summer visits to the North Shore … Essex clams, tennis, various adventures on the coast. Also my visits to him in Toronto, where he led the Multicultural History Society of Ontario and introduced me to seemingly limitless exotic culinary experiences.

I still often have questions I wish I could ask Bob on issues ranging from family history to world tensions. I can imagine his presumably sharp and funny take on the explosion in amateur ancestry.

After being surprised at how little Bob’s important work intersected with the age of the Internet, I was recently cheered to see many references to Bob’s work.

But even with all his fascinating work in multiculturalism, it’s Bob’s humanity that sticks with me. Check out this poem of his …

Blueberries

It took the better half of the day

to reach the woods and piggery

up beyond the Lynn road

blueberrying with Capt.

He knew the route. the sun,

prickly shrubs and soggy spots.

He knew the granite outcroppings

beneath the berry bushes

the snakes nesting there—

garter, milk, and copperhead.

He overturned the stones with sticks

making startled humus steam

and baby snakes wriggle

like green tendrils at low tide

of shorewall seaweed.

Beyond the ledge was the piggery fence.

Sows and swill, the farmer’s share

of Salem’s scavenger economy.

The sun made us giddy, the brambles stung

we dreamed Capt.’s tales of bears and lynx,

and so a grunting sow, a piglet’s squeal,

a towhee rustling through the leaves

made the stooping berrypickers freeze.

My sister and I believed in bears

in Salem’s woods.

The old man’s stories made us surer,

gave circumstances and color to the dream.

The fear we knew to be untrue,

for what they didn’t convert,

the Puritans drove away or slew,

and that included beasts as well as men.

Then to show our own descent,

our links in time and space to them.

We threw the little snakes by handfuls

as morsels for the hungry sows

propitiating bears and

exorcizing woods.

Making the ledge

forever safe for blueberrying.

John O. Harney is a writer and retired executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

John O. Harney: My new parcels of volunteer life

The author overseeng coneflowers at the Rose Kennedy Greenway

Inspired by the story of George Orwell caring for his roses while writing masterpiece essays, I looked forward to a retirement spent partly watching over the plants on Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway. Sure, I got a bit stressed over whether the fading white blooms I saw were Virginia Sweetspire Itea Virginica or Witch Alder Fothergilla. As I had earlier over whether the purple perennials were Salvia or Veronica. But for the most part, my most stressful dilemma would be choosing which dim sum joint to hit near the Greenway’s Chinatown “parcel.”

As for my own essays, never brilliant like Orwell’s, they’ve slowed to a crawl since the beginning of this year, when after 30-plus years, I left the editorship of The New England Journal of Higher Education and began volunteering in phenology at the Greenway. (Regrettably, I may have planted a kiss of death on the journal, where you’ll see few new postings since my departure.)

Fearing America’s increasing flirtations with nationalism and Us vs. Them politics, I also began volunteering in English language teaching at the Immigrant Learning Center, in Malden, Mass.

On the Greenway

Early on, a Greenway staff member gave me her cell number in case I needed help ID’ing plants or, she quipped, if I needed to report anything unusual on the Greenway, “like a body.” A staffer mentioned during an earlier volunteer pruning day, “the Greenway is enjoyed by all kinds of people so watch out for needles as you clean up around plants.”

Then Greenway retirement gig also reminded of my work days, attending economic conferences at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, directly across the street from Parcel 22. That Dewey Square stretch of gardens was then housing Boston’s version of the Occupy Wall Street movement. (Sometimes, feeling out of place in my ill-fitting suit, I wished that I was helping their cause rather than returning to my office.) By now, though, the whiff of rebellion had yielded to a riot of pink and white Coneflowers Echinacea and a Boxwoody imperial fragrance in the parcel near the Fed.

Sunflowers on the Greenway

Earlier in the summer, the Greenway folks worked with local nonprofit groups from Roxbury to plant massive stands of Sunflowers, the unofficial flower of my daughter-in-law’s war-torn Ukraine. In August, the Sunflowers bloomed gloriously around the vent and mural on Parcel 22. But more recently, it looked like some force had crashed into the middle of the main patch, pushing the Sunflower stocks outward like the Tunguska event in Siberia.

Nearby, I’m fascinated by the Pawpaw tree because of my childhood memory of a nursery rhyme that went: “Where, oh where oh where is Johnny [personalized for me], way down yonder in the Pawpaw patch.”

I’m also drawn to the paver my kids and I placed at the corner of Milk Street for my wife, saying “Joanne Harney We Love You.” I still check on the paver when I go to visit my “parcels.” And it looks sharp, as if a good angel has been coming along and buffing it. A half-joke in my house was that we could all meet there in case of disaster (though the urban location 500 feet or so from a rising sea may not be a safe haven forever).

I am also heartened by the Greenway’s small steps in food equity. In the edible garden, a sign reads:

ATTENTION GARDEN VISITORS: Please help us share the harvest!

The produce grown here is specifically cultivated and donated to our local homeless shelters.

Kindly refrain from picking the food to ensure it reaches those in need.

Your cooperation will help us make a difference in our community.

I’ve noted the ferny asparagus and carrots as well as strong corn and tomatillos. One day, a woman emerged from near a small houseless encampment and asked me if there was any mint in the garden. I said I thought there was some in Parcel 22, to which, she seemed relieved, saying that her husband, who camps out with her, eats it from time to time. A staffer suggested some of the Milkweeds in the gardens were planted secretly by visitors hoping to encourage Monarch Butterflies on the Greenway.

Ricinus

But I assume all know the stay clear of the purplish-leaved Ricinus growing in a galvanized bucket on Parcel 22 … host of the castor bean but also of famously deadly ricin.

My confines became Pearl, Congress and Purchase streets and Atlantic Avenue. The key reference points in my geographic descriptions were: the restaurant Trade, the Brazilian consulate with its national flag, the Native American Land Acknowledgment, the various Greenway maintenance sheds (and hangouts for the houseless), the Fed, the Red Line plaza, the Purchase Street tunnel (a reminder that the Greenway sits just a matter of a few feet over an interstate highway) and my favorite landmark, the Japanese Umbrella Pine in Parcel 21.

At the Immigrant Learning Center

Given America’s xenophobia, I also wanted to use my newly found time to help marginalized people in immigrant communities. I had tried to cover their predicament editorially in the journal. But retirement brought a new commitment. Reasoning that my decades of editing was something like teaching English, I applied for volunteer teaching of adults at the Immigrant Learning Center.

It has been a great pleasure to work with new immigrants from Haiti, Vietnam, China, Syria, Rwanda and elsewhere. When I helped one Syrian student read a children’s book about Winnie the Pooh, the description of the One Hundred Acre Wood reminded me of the Greenway work.

Many of the countries of origin of students at the center share a history of exploitation by the U.S., where these innocents fervently want to settle.

I have covered a few subjects probably too subtly for non-English speakers. Holidays, for example. I explained that Memorial Day was a day to remember people who had died. Sure, it was originally people who died in wars, but really anyone who’s died. Back to my old view that people who resisted the Vietnam War were as worthy of honor on Veterans Day as those who served.

Of Juneteenth, I tried to explain that while Americans say that they believe all are created equal, the concept of slavery clearly ran counter to that. And I reminded the many Haitians in the class that Haiti was among the many countries that abolished slavery before the U.S. I also mentioned to the Haitian students that I was rooting for the Haiti women’s national soccer team in the World Cup. To which, I was asked to explain the meaning of “rooting for.”

The immigrant lessons also teach much about the U.S. economy. One exercise focuses on occupations such as dishwasher, house cleaner, delivery driver and “manager.” One student noted getting a pay raise of 50 cents per hour—a modest honor. In one lesson, my lead teacher, himself a Haitian immigrant, drilled students on the difference between odd from even numbers … somewhat unimportant I thought until he noted smartly that Americans increasingly were getting shot knocking on the wrong doors.

Too much analytics

My aversion to analytics—clearly taking over the worlds of higher education and journalism that I recently fled—hobbles me even in volunteer life.

The Greenway folks prefer describing bloom progress with number rankings rather than comments. To make matters worse, the rankings are not the usual, 1 is best and 5 is worst, or vice versa. Instead, 3 is the best. It is peak flowering, then 4 is much less and 5 about done. 1 signifies just starting to bloom and 2 is progressing. Even an amateur like me can take a stab at peak flowering, but discriminating between 1 and 2 and between 4 and 5 is much tougher. And what to think of the Lamb’s Ear whose foliage graced two large banks in Parcel 21 but only shot out one flower on my watch.

The ranking snafu is familiar to anyone pestered by evaluation requests whenever you buy a product or service these days. As a former writer and editor, I’m happier with my rough notes than my arbitrary rankings.

I tell myself I may be a small part of a grand repository of plant info, or at least some effort to introduce identifying plant tags, which the Greenway lacks. Or an “interactive bloom tracker,” which sees to be always out of order when I try it. Of course, the data may be going into a black hole. But for me, the exercise is worth it.

The immigration educators understandably discourage use of synonyms, puns and anecdotes that may just confuse new English learners. All tough for a guy who considered himself “thoughtful,” but may have really been “wordy” and “unfocused.”

John Harney: Many thanks, New England

John O. Harney

From, The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

In October, I wrote to NEBHE colleagues to let them know I would be retiring from the organization and the editorship of its New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE) in early January 2023.

While NEBHE has been my job, NEJHE has been my passion. I joined NEBHE in 1988 and, in 1990, became editor of NEJHE (then called Connection: New England’s Journal of Higher Education and Economic Development).

Thirty-four years for one outlet. Sometimes I forget I’m even that old.

I looked at the journal editions, printed on paper until 2010, as pieces of art (albeit imperfect ones) as much as a news service. The best issues I thought were like our own “Sgt. Pepper’’ album. Today, reminds me a bit of Bob Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm.’’

I’ll miss working with our distinguished authors, sometimes goading them into writing their bylined commentaries—usually for no fee. Those writers also happened to be our readers … a community of policymakers, practitioners and regionalists we described variously as “opinion leaders” in the old days, “thought leaders” more recently. All bound together by an interest in higher education and New England (which I recall was a tough audience to quantify for analytically retentive advertisers).

I’ll also miss the editorial “departments” we developed, such as Data Connection, a sort of spinoff of the Harper’s Magazine Index, but with a New England and higher education flavor. Reflective of a certain “NEJHE Beat,” these items—like a lot of NEJHE content—track along a unique constellation of issues anchored in higher education but also moored to social justice, economic and workforce development, regional cooperation, quality of life, academic research, workplaces and other topics that, together, say New Englandness.

In our print days, I was especially invested in my Editor’s Memo columns that opened every edition from 1990 to 2010.

A few of these Editor’s Memos noted the transition from Connection to NEJHE, an illness that forced me to take leave in 2007 and the journal’s shift from print to all-Web in 2010.

Many pieces looked at the future of New England. One touched on our mock Race for Governor of the State of New England. That exercise helped midwife New England Online, an attempt by NEBHE and partners to take advantage of then-new networking technologies to provide something of a clearinghouse of all things New England—a bit unfocused perhaps, but poignant in a region where, the “winner” of that fantastic New England governor’s race, then state Rep. Arnie Arnesen of New Hampshire, quipped that the capital of New England should not be, say, Boston or Hartford, but instead something along the lines of “www.ne.gov.” (See our house ad.)

The House that Jack Built focused on the first NEBHE president I worked with, Jack Hoy, who passed away in 2013. Jack was a mentor who pioneered understanding of the profound nexus between higher education and economic development that is now taken for granted and that served as the basis for the journal’s name, Connection.

Among other of these commentaries and columns, several focused on the magical relationship between higher-education institutions and their host communities. Even in the emerging age of a placeless university, there is no diminishing the correlation between campuses and good restaurants, bookstores, theaters and other amenities, driven by faculty, students and otherwise smart locals.

In this vein, I was personally sustained for more than three decades by NEBHE’s home in Boston. Despite its difficult racial past (which NEBHE and NEJHE have attempted to address), the Hub, and next-door Cambridge, comprise Exhibit A in such college-influenced communities. Indeed, our street in Downtown Crossing has offered a lesson in the region’s changing economy, being transformed from a strip of small nonprofits that wanted to be close to Beacon Hill, to dollar stores, to, most recently, chic restaurants and bars. The foot traffic, meanwhile, has become much more collegiate as Emerson College and Suffolk University have expanded downtown.

I noted in my letter to colleagues that I strongly believe that the regional journal is a key strength of NEBHE that should continue to be appreciated and bolstered.

For years, we characterized Connection and NEJHE as America’s only regional journal on higher education and its impact on the economy and quality of life. In addition, the topics we’ve covered are just too important to cast our gaze elsewhere. New England’s challenging demography—where some states now see more deaths than births—means there are fewer of us to nourish a workforce and exercise clout in Congress. This all makes our historic strength in attracting foreign students and immigrants to build our communities and industries all the more important. Growing chasms in income and wealth between chief executives and employees, meanwhile, agitate antidemocratic and racist forces. While too many critics diss snowflakes, dangerous trauma grows among students and staff. And a pandemic (that is not over) exposed our fault lines, but also showed the promise of joining together behind scientific breakthroughs … and behind one another.

NEBHE President Michael Thomas and I agreed that the weeks leading up to my retirement will provide opportunities to celebrate the journal’s four decades of contributions to the region—as well as to think about its future and the ways NEBHE can best inform and engage stakeholders going forward.

But these are tough times for independent-minded journalism—especially in the quasi-free press world of association journalism, where the goal is to be objective, but for a cause (and ours is generally a good one). NEBHE has launched a job search for a director of communications and marketing. To be sure, my functions at NEBHE also included PR and media relations and style maven (editorial style that is), and those too are key tasks that NEBHE must continue to fulfill. (Full disclosure, I always urged NEJHE authors to make their pieces “issue-oriented” and “avoid marketing.” The goal for the journal was to be thoughtful and candid.)

Just keep it real.

Here’s to the future of NEBHE and NEJHE.

John O. Harney is the executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Editor’s note: New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is a former member of the Advisory Board of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

John O. Harney: Some intriguing N.H. and other indices

“The View from Andrew’s Room Collage Series #8″, by Timothy Harney, a professor at the Monserrat College of Art, Beverly, Mass.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Percentage of U.S. counties where more people died than were born in 2021: 73% University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of National Center for Health Statistics data

Number of additional births that would have occurred in the past 14 years had pre-Great Recession fertility rates continued: 8,600,000 University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy analysis of National Center for Health Statistics data

Percentage of Americans who told the Annenberg Science Knowledge survey in July 2022 that they have returned to their “normal, pre-COVID-19 life”: 41% Annenberg Public Policy Center

Percentage who said that in January 2022: 16% Annenberg Public Policy Center

Percentage of teenagers who reported that their post-high school graduation plans changed between the March 2020 start of the COVID-19 pandemic and March 2022: 36% EdChoice\

Change during that period in percentage of teenagers who said they planned to enroll in a four-year college: -14% EdChoice

Ranks of “Self Discovery,” “Finances” and “Mental Health” among reasons for change in plans: 1st, 2nd, 3rd EdChoice

Percentage of college students who say they will pay their education expenses completely on their own: 67% Cengage

Percentage who say they have $250 or less left after paying for education costs each month: 46% Cengage

Ranks of “lower tuition,” “more affordable options for course materials” and “lowering on-campus costs, such as housing and meal plan costs” among actions students say their colleges could take to lower education costs: 1st, 2nd, 3rd Cengage

Percentage of Americans who graded their local public schools with an A or a B in 2019: 60% Education Next

Percentage who gave those grades in 2022 after two years of COVID-related disruption: 52% Education Next

Percentage of aircraft pilots and flight engineers who are women: 5% U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Percentage of aircraft pilots and flight engineers who are Black: 4% U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Percentage of aircraft pilots and flight engineers who are Asian: 2% U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Percentage of aircraft pilots and flight engineers who are Hispanic: 6% U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Approximate percentage increase in sworn personnel in New Hampshire State Police, from 2001 to 2020: 30% Concord Monitor

Percentage of New Hampshire State Police personnel who are white: 95% Concord Monitor reporting of N.H. Department of Safety data

Percentage of New Hampshire State Police personnel who are men: 91% Concord Monitor reporting of N.H. Department of Safety data

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

John O. Harney: Marketing abortion ruling; armed youth; ‘don’t say gay’ in Greenwich; not the ‘Flutie Effect’

Map by Tpwissaa

Greenwich, Conn., High School

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Could the anti-choice, forced-birth culture of the U.S. Supreme Court and many U.S. states present an advantage for New England economic boosters?

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker told reporters that he had heard from a lot of companies that the recent Supreme Court decision removing the federal protection of the right to abortion may offer a big opportunity for Massachusetts to attract some employers whose employees would want access to reproductive-health services. Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont called on businesses in states that limit abortion access to consider relocating to Connecticut.

In the context of choosing where to start or expand a business, big employers have occasionally written off New England as “old and cold” compared with economically and meteorologically sunnier spots. However, a 1999 poll by the University of Connecticut’s Center for Survey Research and Analysis, while admittedly dated, found an interesting niche for New England. International site-selection consultants, accustomed to Europe’s pricey, regulated environments, were less concerned with New England’s notoriously high costs than domestic site-selection pros. Key issues for the international consultants were access to higher education, an educated workforce and good infrastructure.

Peter Denious, chief executive of Advance CT, a business-development organization, recently told the Connecticut Mirror that such issues as diversity, equity and inclusion—and the state’s commitment to clean energy—could all help Connecticut align with the corporate goals of certain companies.

Our culture of active government, unionization and especially our human- resource development, could bode well once again in relatively enlightened New England.

Anti-semitism rising: The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) reported 2,717 anti-semitic incidents of assault, harassment and vandalism in 2021 in the U.S., the highest number since the ADL began tracking anti-semitic incidents in 1979, according to the group’s annual Audit of Antisemitic Incidents. These included more than 180 anti-semitic incidents in New England. And nationally, 155 anti-semitic incidents were reported at more than 100 college campuses. Meanwhile, tension between anti-semitism and anti-zionism, including the boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) movement, is challenging on campuses and beyond

Packing heat. More than 1 million U.S. adolescents (ages 12 to 17) said they had carried a handgun in 2019-20, up 41% from about 865,000 in 2002-03, according to a study by researchers at Boston College’s Lynch School of Education and Human Development, using data from the National Survey on Drug Use & Health. The socio-demographic profile of the gun carriers also changed. Carrying rates grew from 3.1% to 5.3% among white adolescents, from 2.6% to 5.1% among higher-income adolescents, and from 4.3% to 6.9% among rural adolescents between, while rates among Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native and lower-income adolescents decreased.

“Don’t Say Gay” here? In April, Mount Holyoke College President Sonya Stephens wrote here that Florida legislation dubbed by opponents the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, was part of a nationwide wave of proposal laws linking divisive issues of race, sexual orientation and gender identity to parents’ concerns about what their children are being taught in public schools. These bills not only undermine the real progress that LGBTQ+ people have made in society over the past 50 years, Stephens wrote, but they also further erode trust in some of our most under-compensated public servants: school teachers and administrators.

On July 1, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona noted that the Florida parents and families he’d spoken with said the legislation doesn’t represent them and that it put students in danger of bullying and worse mental health outcomes.

In Cardona’s home state of Connecticut, meanwhile, the Greenwich School Board adopted a new Title IX policy unanimously, but not without controversy. Edson Rivas and Colin Hosten of the Fairfield County-based Triangle Community Center Board of Directors wrote in Connecticut Viewpoints that the policy adopted by the Greenwich School Board “conspicuously removes any language referring to gender identity and sexual orientation” which was part of the original version of the policy introduced last fall. The board replied that “this policy covers all students, whether or not certain language is included.” But Rivas and Hosten aren’t buying it. “If the substance of the policy remains the same, as they say, then the only effect of removing the language about gender identity and sexual orientation is the linguistic pseudo-erasure of the LGBTQ+ community in Greenwich Public Schools.”

Truth to tell: Recently, the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) named 75 higher-education institutions to participate in the 2022 Institute on Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation (TRHT) Campus Centers as part of an effort to dismantle racial hierarchies.

As we at NEBHE and others have wrestled with a “reckoning” on race, gender and so many other wrongs, the “truth and reconciliation” concept has always made sense to me. Check out, for example, the thoughtful book Honest Patriots exploring how true patriots in post-World War II Germany, post-apartheid South Africa and the U.S. in the the aftermath of slavery and the genocide of Native Americans loved their country enough to acknowledge and repent for its misdeeds.

Under the AAC&U initiative, campus teams develop action plans to advance the parts of the TRHT framework: narrative change, racial healing and relationship building, separation, law and economy. The institute helps campus teams to prepare to facilitate racial-healing activities on their campus and in their communities; examine current realities of race relations in their communities and the local history that has led to them; identify evidence-based strategies that support their vision of what their communities will look, feel and be like when the belief in the hierarchy of human value no longer exists, and learn to pinpoint critical levers for change and to engage key stakeholders.

Among participating New England institutions: Landmark College, Middlesex Community College, Mount Holyoke College, Suffolk University, the University of Connecticut and Westfield State University.

Another problem with over-incarceration. NEBHE has published a policy brief about the effects of higher education on incarcerated people in New England prisons and jails—and increasingly broached conversations about the dilemmas created by the world’s biggest incarcerator — America. Now, another byproduct surfaces: Children with an incarcerated parent have exceedingly low levels of education. The most common education level for respondents from a low-income family who had an incarcerated parent was elementary school, according to research by a group of Wake Forest University students who put together an article for the Nation Fund for Independent Journalism. The students set out to understand how the academic achievement, mental health and future income of children of incarcerated parents compare to those with deceased parents. Just under 60% as many respondents with an incarcerated parent completed a university education compared to the baseline of respondents with neither an incarcerated nor deceased parent.

Acquisition of Maguire: I first heard the term “Flutie Effect” in the context of former Boston College Admissions Director Jack Maguire. The term refers to the admissions deluge after the BC quarterback Doug Flutie threw the famed Hail Mary pass (caught by the less-famous Gerald Phelan) in 1984. Flutie won the Heisman Trophy, then pursued a pro career, first with Donald Trump’s New Jersey Generals in the USFL and then in the Canadian Football League, with a few bumpy stops in the NFL.

But Maguire attributed BC’s good fortune not to the diminutive quarterback but to the college’s “investments in residence halls, academic facilities, and financial aid.” In 1983, Maguire, a theoretical physicist by training, founded Maguire Associates and introduced the concept of “enrollment management,” combining sophisticated analytical techniques, customized research and deep experience in education leadership with a genuine enthusiasm for client partnerships. Maguire became a sort of admissions guru whose insights we have been pleased to feature.

Now, higher-education marketing and enrollment strategy firm Carnegie has announced it is buying Maguire Associates. Not to be confused with the foundation that administered the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, which recently moved to the American Council on Education, nor the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which has encouraged disarmament, this Carnegie, also founded in the 1980s and based in Westford, Mass., is formally known as Carnegie Dartlet LLC. Its pitch: “We are right definers. We are your intelligence. We are truth revealers. We are your clarity. We are obstacle breakers. We are your partners. We are audience shapers. We are your connection. We are brand illuminators. We are your insight. We are story forgers. We are your voice. We are connection creators. …”

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

The status of youth engagement in American democracy

At the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate at the UMass Boston campus, on Columbia Point: Inside the replica of the U.S. Senate chamber.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In the following Q&A, NEJHE Executive Editor John O. Harney asks Mary K. Grant, president of the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, in Boston, about the institute’s work connecting postsecondary education to citizenship and upcoming elections. Edward M. Kennedy (1932-2009) was U.S. senator from Massachusetts in 1962-2009. He became known as a “liberal lion” of that body.

Harney: What did the 2016 and 2018 elections tell us about the state of youth engagement in American democracy?

Grant: We are seeing a resurgence of interest in civic engagement, activism and public service among young people. From 2014 to 2018, voter turnout among 18- to 29-year-olds increased by 79%, the largest increase among any group of voters.

The 2016 election was certainly a catalyst for galvanizing renewed interest. Since 2016, we have seen increases in people being more engaged in organizing platforms, messages and movements to motivate their peers and adults. The midterm elections brought a set of candidates who were the most diverse in our history, entering politics with urgency and not “waiting their turns” to run for office. One of the most encouraging findings was that those who felt most frustrated were more likely to vote.

While young-voter turnout in the 2018 election was historically high, it was still just 31% of those eligible to vote. Democracy depends on the voice of the people. And a functioning democracy depends on participation, particularly in polarized times. Senator Kennedy said “political differences may make us opponents, but should never make us enemies.” He envisioned the Edward M. Kennedy Institute as a venue for people from all backgrounds to engage in civil dialogue and find solutions with common ground.

As a nonpartisan, civic education organization, the institute’s goal is to educate and engage people in the complex issues facing our communities, nation and world. Since we opened four years ago, we have had more than 80,000 students come through our doors for the opportunity to not only learn how the U.S. government works, but also to understand what civic engagement looks like. All of us at the Kennedy Institute see how important it is to give young people a laboratory where they can truly practice making their voices heard and experience democracy; our lab just happens to be a full-scale replica of the U.S. Senate Chamber.

Harney: How else besides voting do you measure young people’s civic citizenship? Are there other appropriate measures of activism or political engagement?

Grant: Voter turnout is one measure, but civic engagement is needed every day. Defined broadly, activism and civic citizenship are difficult to measure. We engage in our local, state and national communities in so many ways.

Our team at the institute values reports like “Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools” that discuss how the challenge in the U.S. is not only a lack of civic knowledge, but also a lack of civic skills and dispositions. Civic skills include learning to deliberate, debate and find common ground in a framework of respectful discourse, and thinking critically and crafting persuasive arguments and shared solutions to challenging issues. Civic dispositions include modeling and experiencing fairness, considering the rights of others, the willingness to serve in public office, and the tendency to vote in local, state and national elections. To address the critical issues and make real social change, we need a better fundamental understanding of how our government works. And we need better skills for healthy, respectful debate.

Harney: What are the key issues for young voters?

Grant: The post-Millennial generation is the most racially and ethnically diverse generation in our history. Only 52% identify as non-Hispanic whites. As they envision their future livelihoods in an increasingly automated workplace, they are concerned about climate change and how related food security may affect the sustainability of daily life and they are concerned about income inequality, student debt, gun violence, racial disparities, and being engaged and involved in their communities.

The institute’s polling data indicated that interests for 18-34-year-olds were reflective of society as a whole, but gun rights and gun control, education and the economy would be among the most important as they are deciding on congressional candidates in the next election.

Young people are focused on the complex global issues that concern us all but with added urgency. A Harvard Institute of Politics Youth Poll this spring found that 18-29-year-old voters do not believe that the baby boomer generation—especially elected officials—“care about people like them.” And, they expressed concern over the direction of the country.

Harney: Are there any relevant correlations between measures of citizenship and enrollment in specific courses or majors?

Grant: In a democracy, we need all majors. And more importantly, we need students and graduates to know how to work together. In a global economy, people in the sciences, business and engineering work right next to people in the fields of social sciences. I had the privilege of leading two of the finest public liberal arts college and universities in the country. I am a firm believer that regardless of disciplinary area, problem-solving requires us to ask questions, to be curious and open-minded, to think critically and creatively, incorporate a variety of viewpoints and work in partnership with others. We need to understand how you take an idea, move it along and make it into something that can improve the common good.

Harney: Are college students and faculty as “liberal” as “conservative” commentators make them out to be?

Grant: From my own work in higher education, I can say that there is diversity of perspectives and viewpoints on college campuses, which is encouraging and exciting. Liberals and conservatives are not unique in the ability to hold on quite strongly to their own viewpoints. Anyone who has ever witnessed a group of social and natural scientists discuss research methodologies can attest to that. We all need to learn how to listen to ideas other than our own.

Harney: What are ways to encourage “Blue-State” students to have an effect on “Red-State” politics and vice versa?

Grant: Part of the country’s challenge in civil discourse is that we stop listening or we are listening for soundbites to which we overreact. One of the most important skills that we can develop is the ability to listen actively. It’s truly remarkable what can happen when students have an opportunity to get to know and work and learn with their peers across the country and around the world.

What we’re finding in our programs is that people are hungering for conversation, even on difficult matters. It’s similar to the concept of creating spaces on college campuses where you can intentionally connect with people. This coming fall, we’re using an award that we earned from the Annenberg Public Policy Center, at the University of Pennsylvania, to pilot a program called “Civil Conversations.” The program is designed to help eighth through 12th grade teachers develop the skills necessary to lead productive classroom discussions on difficult public policy issues. We’re starting in Massachusetts and plan to expand to all the blue, red and purple states.

And for those coming to the institute, we convene diverse perspectives through daily educational and visitor programs where people can talk with and listen to others who might be troubled or curious about the same things you are. Our public conversation series and forums bring together government leaders with disparate ideologies and from different political parties who are collaborating on a common cause; we host special programs that offer insight into specific issues and challenges facing communities and civic leaders, and what change-makers are doing about it.

Harney: What role does social media play in shaping engagement and votes?

Grant: Social media has fundamentally changed not only how we get our information, but how we interact with each other. According to a Harvard Institute of Politics Youth Poll, more than 4-in-5 young Americans check their phone at least once per day for news related to politics and current events.

As social media reaches more future and eligible voters, and when civic education is lacking, those who depend on social media platforms are at risk of consuming inaccurate information. This underscores not only the need for robust civic education programs, but also those in media literacy.

Harney: How can colleges and universities work together to bolster democracy?

Grant: Anyone who spends time around young people or on a college campus feels their energy and can’t help but come away with a renewed sense of hope. Colleges can continue to work together and advocate for unfettered access to higher education for students in all areas of the country. More specifically, they can engage with organizations like Campus Compact, a national coalition of more than a thousand colleges and universities committed to building democracy through civic education and community development.

Harney: How will New England’s increased political representation of women and people of color affect real policy?

Grant: The increasingly diverse representation helps to broaden and deepen the range of perspectives, ideas and viewpoints that influence public policy. There is also a renewed energy that is generated and it encourages next generation leaders to get involved, run for office, work on campaigns and make a difference in their communities. The institute has held several Women in Leadership programming events that highlight the lack of gender equity and racial diversity in public office and provide opportunities for women to network and learn more about the challenges and the opportunities.

Harney: Do young voters show any particular interest in where candidates stand on “higher education issues” such as academic freedom?

Grant: Students may not be focused on “higher education issues,” per se, but they do have a lot to say about accessibility and affordability. This generation is saddled with an enormous amount of student loan debt. That is certainly one of their greatest concerns, particularly when it comes to the 2020 presidential race.

Academic freedom is important in making colleges and universities welcoming to the exchange of differing ideas, which is a bedrock of democracy. As a former university chancellor, I believe that it is essential to create an environment where we welcome a diversity of opinion. We need to model the ability to listen to and consider viewpoints that may be very different from our own. We need to show students that we can sit down with people who think differently, find common ground, and even respectfully disagree. That’s a key part of what the Edward M. Kennedy Institute is all about.

John O. Harney: Some big changes at the top

The (Brutalist) Federal Reserve Bank of Boston tower, at the edge of the Boston financial district.

— Photo by Fox-orian

(New England Diary is catching up with this report, first published Feb. 15.)

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston named University of Michigan Provost Susan M. Collins to be the bank’s next president and CEO. An international macroeconomist, Collins will be the first Black woman to lead a regional bank in the 108-year history of the Fed system. In addition to being the University of Michigan’s provost and executive vice president for academic affairs, Collins is the Edward M. Gramlich Collegiate Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics. She holds an undergraduate degree from Harvard University and a doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She will succeed Eric Rosengren, who retired in September after 14 years leading the Boston Fed.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology President L. Rafael Reif announced he will leave the post he has held for the past decade at the end of 2022. A native of Venezuela, Reif began working at MIT as an electrical engineering professor in 1980, then served seven years as provost before being named president in 2012. Among other things, he presided over a $1 billion commitment to a new College of Computing to address the global opportunities and challenges presented by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and oversaw the revitalization of MIT’s physical campus and the neighboring Kendall Square in Cambridge, Mass. Reif said he will take a sabbatical, then return to MIT’s faculty in its Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

Tufts University President Anthony Monaco told the campus that he will step down in the summer of 2023 after 12 years leading the university. A geneticist by training, Monaco ran a center for human genetics at Oxford University in the U.K. and, at Tufts, worked with the Broad Institute on COVID-19 testing programs that helped universities return to in-person learning. Among his accomplishments, Monaco oversaw the university’s 2016 acquisition of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston as well as the removal of the “Sackler” name from its medical school after the Sackler family and its company, Purdue Pharma, were found to be key players in the opioid crisis.

The Biden administration tapped David Cash, dean of the John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at UMass Boston and former commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, to be the regional administrator for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in New England.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The England Journal of Higher Education.

John O. Harney: The state of the New England states as COVID winds down (for now?)

Regions of New England:

1. Northwest Vermont/Champlain Valley

2. Northeast Kingdom

3. Central Vermont

4. Southern Vermont

5. Great North Woods Region

6. White Mountains

7. Lakes Region

8. Dartmouth/Lake Sunapee Region

9. Seacoast Region

10. Merrimack Valley

11. Monadnock Region

12. Aroostook

13. Maine Highlands

14. Acadia/Down East

15. Mid-Coast/Penobscot Bay

16. Southern Maine/South Coast

17. Mountain and Lakes Region

18. Kennebec Valley

19. North Shore

20. Metro Boston

21. South Shore

22. Cape Cod and Islands

23. South Coast

24. Southeastern Massachusetts

25. Blackstone River Valley

26. Metrowest/Greater Boston

27. Central Massachusetts

28. Pioneer Valley

29. The Berkshires

30. South County

31. East Bay

32. Quiet Corner

33. Greater Hartford

34. Central Naugatuck Valley

35. Northwest Hills

36. Southeastern Connecticut/Greater New London

37. Western Connecticut

38. Connecticut Shoreline

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

“This Covid-19 pandemic has been part of our lives for nearly two years now. It’s what we talk about at our kitchen tables over breakfast in the morning, and again over dinner at night. It gets brought up in nearly every conversation we have throughout the day, and it’s a topic at nearly every special gathering we attend,” Rhode Island Gov. Daniel McKee noted in his recent 2022 State of the State address.

Indeed, that was a consistent theme among all six New England governors’ 2022 State of the State speeches. As were plugs for innovation in healthcare, especially mental health, housing, workforce development, climate strategies, children’s services, transportation, schools, budgets and, with varying degrees of gratitude, acknowledgement of federal infusions of relief money.

Here are links to the full New England State of the State addresses, highlighting some key points from the beat:

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont’s 2022 State of the State Address

“Our budget invests 10 times more money than ever before in workforce development—with a hyper focus on trade schools, apprentice programs and tuition-free certificate programs where students of all ages can earn an industry-recognized credential in half the time, with a full-time job all but guaranteed.

This investment will train over 10,000 students and job seekers this year in courses designed by businesses around the skills that they need.

This isn’t just about providing people with credentials; this is about changing people’s lives.

A stay-at-home mom whose husband lost his job earned her pharmacy tech certificate in three months and now works at Yale New Haven Hospital.

A man who was homeless was provided housing, transportation, a laptop and training. He’s now a user support specialist for a large tech company.

These are just two examples of opportunities that completely change the course of someone’s life.

We are working with our partners in the trade unions to develop programs for the next generation of laser welders and pipefitters. Building on the amazing partnership between Hartford Hospital and Quinnipiac University, we are also ramping up our next generation of healthcare workers.

I want students and trainees to take a job in Connecticut, and I want Connecticut employers to hire from Connecticut first! To encourage that, we’re expanding a tax credit for small businesses that help repay their employees’ student loans. More reasons for your business to hire in Connecticut, and for graduates to stay in Connecticut—that’s the Connecticut difference.”

Maine Gov. Janet Mills’s 2022 State of the State Address

“It is also our responsibility to ensure that higher education is affordable.

And I’ve got some ideas to tackle that.

First, I am proposing funding in my supplemental budget to stave off tuition hikes across the University of Maine System, to keep university education in Maine affordable.

Secondly, thinking especially about all those young people whose aspirations have been most impacted by the pandemic, I propose making two years of community college free.

To the high school classes of 2020 through 2023—if you enroll full-time in a Maine community college this fall or next, the State of Maine will cover every last dollar of your tuition so you can obtain a one-year certificate or two-year associate degree and graduate unburdened by debt and ready to enter the workforce.

And if you are someone who’s already started a two-year program, we’ve got your back too. We will cover the last dollar of your second year.”

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s 2022 State of the State Address

“We increased public school spending by $1.6 billion, and fully funded the game-changing Student Opportunity Act.

We invested over $100 million in modernizing equipment at our vocational and technical programs, bringing opportunities to thousands of students and young adults.

We dramatically expanded STEM programming, and we helped thousands of high school students from Gateway Cities earn college credits free through our Early College programs.”

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s State of the State Address

“Our way of life here in the 603 is the best of the best.

We didn’t get here by accident—we did it through smart management, prioritizing individuals over government, citizens over systems, and delivering results with the immense responsibility of properly managing our citizens tax dollars.

As other states were forced to buckle down and weather the storm, we took a more proactive approach in 2021. In just the last year, we:

• Cut the statewide property tax by $100 million to provide relief to New Hampshire taxpayers

• Cut the rooms and meals tax

• Cut business taxes—again

• Began permanently phasing out the interest and dividends tax

And while we heard scary stories of how cutting taxes and returning such large amounts of money to citizens and towns would ‘cost too much’, the actual results have played out exactly as we planned, record tax revenue pouring into New Hampshire, exceeding all surplus estimates, allowing us to double the State’s Rainy Day Fund to over $250 million.”

Rhode Island Gov. Daniel McKee’s State of the State Address

“We all know that the economy was changing well before the pandemic. A college degree or credential is a basic qualification for over 70 percent of jobs created since 2008. Although we have made great progress over the last decade, there’s more to do.

Let’s launch Rhode Island’s first Higher Ed Academy, a statewide effort to meet Rhode Islanders where they are and provide access to education and training, that leads to a good-paying job. Through this initiative, which will be run by our Postsecondary Education Commissioner Shannon Gilkey, we expect to support over a thousand Rhode Islanders helping them gain the skills needed to be successful in obtaining a credential or degree.

Having a strong, educated workforce is critical for a strong economy—and Rhode Island’s economy is built on small businesses. Small businesses employ over half of our workforce. As these businesses continue to recover from the pandemic, we know that challenges still persist. That’s why in the first several weeks of my administration, I put millions of unspent CARES Act dollars that we received in 2020 into grants to help more than 3,600 small businesses stay afloat.

My budget will call for key small business supports like more funding for small business grants, especially for severely impacted industries like tourism and hospitality. It will also increase grant funding for Rhode Island’s small farms.

As our businesses deal with workforce challenges, I’ll also propose more funding to forgive student loan debt, especially for health-care professionals, and $40 million to continue the Real Jobs Rhode Island program which has already helped thousands of Rhode Islanders get back to work.”

Vermont Gov. Phil Scott’s State of the State Address

“The hardest part of addressing our workforce shortage is that it is so intertwined with other big challenges, from affordability and education to our economy and recovery. Each problem makes the others harder to solve, creating a vicious cycle that’s been difficult to break.

Specifically, I believe our high cost of living has contributed to a declining workforce and stunted our growth. As we lose Vermonters who cannot afford to live, do business or even retire here, that burden—from taxes and utility rates to healthcare and education costs—falls on fewer and fewer of us, making life even less affordable.

With fewer working families comes fewer kids in our schools. But lower enrollment hasn’t meant lower costs and from district to district, kids are not offered the same opportunities, like foreign languages, AP courses or electives. And with fewer school offerings, it is hard to attract families, workers and jobs to those communities.

Fewer workers and fewer students mean our businesses struggle to fill the jobs they need to survive, deepening the economic divide from region to region.

And for years, state budgets and policies failed to adapt to this reality. …

Let’s start with the people already here and do more to connect them with great jobs.

First, our internship, returnship and apprenticeship programs have been incredibly successful, not only giving workers job experience, but also building ties to local employers. To improve on this work, the Department of Labor assists employers to fill and manage internships statewide and we’ll invest more to help cover interns’ wages.

And let’s not forget about retired Vermonters who want to go back to work and have a lot to offer. I look forward to working with Representative Marcotte and the House Commerce Committee on this issue and may others.

Next, let’s put a greater focus on trades training. And here’s why:

We all know we need more nurses and healthcare workers. And as I previewed with {state} Senator Sanders and {state} Senator Balint earlier this week, I will propose investments in this area. But if we don’t have enough CDL drivers, mechanics and technicians, hospital staff won’t get to work; there will be issues getting the life-saving equipment and supplies we need; and we will see fewer EMTs available to get patients to emergency rooms. If we don’t have enough carpenters, plumbers and electricians, or heating, ventilation, air handling and refrigeration techs, there are fewer to construct and maintain the facilities in our health-care system or build homes for the workers we are trying to attract.”

John O. Harney is the executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

John O. Harney: An early look at 2022’s college-commencement season in New England

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE.org)

Long before COVID changed everything, NEJHE and NEBHE’s Twitter channel kept a close eye on New England college commencements. “The annual spring descent on New England campuses of distinguished speakers, ranging from Nobel laureates to Pulitzer Prize winners to grassroots miracle-workers, offers a precious reminder of what makes New England higher education higher,” we bragged. “It is a lecture series without equal.”

In the past two pandemic years, we tracked a lot of postponements and virtual commencements on this beat, as well as Olin College of Engineering’s March 2020 “fauxmencement” ceremony right before coronavirus shut down the campus. Some medical schools at the time moved up graduation dates so graduates could join New England’s COVID-fighting health-care workforce. Dr. Anthony Fauci addressed graduates of the College of Holy Cross, his alma mater.

Going virtual meant hard times for some small New England communities where college-commencement days were crucial to local hospitality providers and the economy. Not to be confused with such larger commencement hosts as the Dunkin Donuts Center for Rhode Island College and Providence College and TD Garden for Northeastern University (switched to Fenway Park during COVID).

This year, as we all hope the pandemic is easing, some New England colleges plan to celebrate not only the class of 2022, but also the classes of 2020 and 2021—for the most part, in person.

Many years, we would pay special attention to the first few announcements of the season. When there was a season. Generally it was spring in the old days. But today’s nontraditional student pursing higher ed on a nontraditional academic calendar might just as easily graduate in January … or any other time for the matter.

As with other stubborn aspects of higher ed, the richest institutions often announced the heavy hitters, though sleepers at quieter places add special value too (think Paul Krugman at Bard College at Simon’s Rock or Rue Mapp at Unity College).

Harvard University, for its part, announced that the principal speaker at its 369th commencement, on May 26, would be New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. Not a bad pick. Ardern has been lauded for her work on climate change and gender equality and, lately on how she has guided New Zealand through COVID. Harvard noted she will be “the 17th sitting world leader to deliver the address.”

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

John O. Harney: Latest people moves at N.E. colleges

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The New Commonwealth Racial Equity and Social Justice Fund named Makeeba McCreary to be the first president of the fund launched by 19 local Black and Brown executives a few weeks after the killing of George Floyd. McCreary recently served as chief of learning and community engagement at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and, before that, as managing director and senior advisor of external affairs for the Boston Public Schools.

University of Maine System Chancellor Dannel Malloy said he would ask system trustees to approve the appointment of Vice President of Academic Affairs and Provost Joseph Szakas as interim president at the University of Maine at Augusta (UMA), while the system searches for a permanent replacement for UMA President Rebecca Wyke. In July, Wyke informed the UMA community that she would step down to become CEO of the Maine Public Employees Retirement System. Szakas will continue in his VP and provost roles while serving as interim leader.

Mark Fuller, who became interim chancellor of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth in January, was named permanent chancellor this week. He previously served for nine years as dean of the UMass Amherst Isenberg School of Management.

Ryan Messmore, former president of Australia’s Campion College, became the fifth president of Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts in Warner, N.H.

Sharale W. Mathis joined Holyoke Community College as vice president of academic and student affairs. A biologist, she previously was dean of academic and student affairs at Middlesex Community College in Connecticut and STEM division director at Manchester Community College. Mathis was an early adopter of Open Educational Resources (OER), utilizing online resources for supplemental instruction designating that course as no cost to students.

Middlebury College appointed Caitlin Goss as its vice president for human resources and chief people officer. Goss previously served as the director of people and culture at Rhino Foods in Burlington, Vt., and as the team leader for employee engagement in global human capital at Bain & Company.

Johnson & Wales University appointed former Norwich University Executive Vice President of Operations Sandra Affenito to be vice chancellor of academic administration, and Mary Meixell, an industrial engineer and former senior associate dean of Quinnipiac University’s School of Business, to be dean of JWU’s College of Business.

Berkshire Community College appointed Stephen Vieira, former chief information officer for the Tennessee Board of Regents and at the Community College of Rhode Island, to be director of information technology at the Pittsfield, Mass., community college.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

John O. Harney: New England and other experts address racial and economic reckoning'

Logo of the Color of Change reform group

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Even in this time when people presume to be having a “racial reckoning,” signs of enduring racial inequity pop up everywhere. From nagging disparities in health—Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) die at higher rates than other groups from COVID-19 and are underrepresented in medical research (except in vile experiments such as in the Tuskegee study) … to the steep declines in Black and Latino students submitting the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) … to Black food-service workers experiencing disproportionate short-tipping for enforcing social-distancing rules … inequality reigns. These persistent forces should be a big deal for New England’s Historically White Colleges and Universities, which are rarely called out as HWCUs.

Some help is on the way. Beside targeting $128.6 billion for the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, $39.6 billion to the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, $39 billion for child care and $1 billion for Head Start, the new $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan does other less visible things to begin to address structural racism. For example, the package provides Black farmers with debt relief and help acquiring land. Black farmers lost more than 12 million acres of farmland over the past century, attributed to systemic racism and inequitable access to markets.

I’ve been trying to monitor the racial-equity conversation mostly via Zoom since the pandemic began. This mention of aid to Black farmers reminded me of something I heard Chuck Collins say at a webinar convened last month by MIT’s Sloan School of Management via Zoom titled “The Inclusive Innovation Economy: Amplifying Our Voices Through Public Policy’’.

Collins is the director of inequality and the common good at the Institute for Policy Studies and a white man. He told of his uncle getting a 1 percent fixed-rate mortgage in 1949 to buy an Ohio farm—a public investment that led his cousins to get on “America’s wealth-building train.” Black and Brown people did not get the same benefits. Collins suggested that systems such as CARES relief should be examined with a racial-equity lens, as should policies such as raising the minimum wage or forgiving student loans. Unquestionably, Black students struggle more than whites with student debt. But with Capitol Hill debating the right amount of debt to forgive, Collins suggested we need to test how well these changes would affect racial inequity.

Dynastic wealth

Noting that we’re living through an updraft of “dynastic wealth,” Collins asked why the U.S. taxes work income higher than income from investments. He pointed out that “50 families in the U.S. that are now in their third generation of billionaires coming online and that represents a sort of Democracy-distorting and market-distorting concentration of wealth and power.”

That distortion could be partly cushioned with a “dignity floor,” said Collins. “It’s not a coincidence that a society like Denmark has much higher rates of entrepreneurship than the U.S. per capita because they have a social-safety net and because they have social investments that create a decency floor through which people cannot all. So if you want to start a business, you know you can take that leap and not end up living in your car.”

We need to disrupt the narrative of “everyone is where they deserve to be,” said Collins. So many entrepreneurs tell their story from the standpoint of I did this. We need to talk about the web of supports and multigenerational advantages behind their ability to take the step they took.

Color-coded

An audience member asked if a bridge could be built to connect the rich and poor. To this, one of the conversation moderators, Sloan School lecturer and former chief experience and culture officer at Berkshire Bank Malia Lazu, quipped that in the U.S., there’s another dimension: The sides of the bridge are “color-coded.”

Lazu and co-moderator Fiona Murray, associate dean for innovation and inclusion at Sloan, agreed that ironically this is how the policies were designed to work. That’s why we need to change how the systems are wired.

It’s not that Black people are less likely to get loans from banks, but that banks are less likely to give loans to Black people, explained Color of Change President Rashad Robinson. Shifting the subject that way, he said, has led to remedies like financial literacy programs for Black people, rather than changes in the policies of big banks.

Color of Change was formed in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, which, like COVID-19, disproportionately hurt Black and Brown people. Narrative is not static, Robinson said, reminding the audience of what people might have unabashedly said in the workplace about LGBT people just 15 years ago.

Moreover, budgets are “moral documents,” Robinson pointed out. So if you say you’re going to prosecute more corruption crimes than street crime, that has to be reflected in budgets. People of color are not vulnerable, they’ve been targeted, added Robinson, who is working on a report that will look at not only Black pain, but also Black joy and how BIPOC are portrayed in stories on TV.

An audience questioner asked which policies actually embed structural racism. Lazu pointed to the U.S. Constitution’s original clause declaring that any person who was not free would be counted as three-fifths of a free individual. For a more modern example, Robinson noted minimum-wage laws that exclude certain kinds of work, originally farm workers and domestic workers, now work usually done by people of color and women. Structural racism is rooted in how our economy is designed, said Robinson. “An equity focus means we’re not just trying to undo harm but we’re trying to create systems and structures that actually move us forward.”

Afraid to bring children into the world

Also last month, the Boston Social Venture Partners convened a Zoom webinar with affiliates in San Antonio and Denver to discuss how nonprofit leaders have struggled to implement strategies that funders require for diversity, equity and inclusion.

The conversation was moderated by Michael Smith, executive director of the Obama Foundation’s My Brother’s Keeper Alliance, based in Washington, D.C. The alliance was created in 2014 in the aftermath of the killing of Trayvon Martin and aimed at addressing opportunity gaps. It works today against the backdrop of the COVID pandemic and resulting school closures, an economic downturn and police violence in communities of color.

Another Obama fellow, Charles Daniels, the executive director of Boston-based Father’s Uplift, explained: “We have a shortage of clinicians of color in this country—sound, qualified therapists who are able to provide that necessary guidance,” he said. “One of the main requests of single mothers bringing their children to us or fathers entering our agency is that they want a clinician of color, someone who looks like them,” he said. “There are conversations they don’t know necessarily how to have with their loved ones about racism, about oppression, about maintaining their dignity and self-respect.”

Daniels noted that constituents are grappling with what to tell sons about getting pulled over by the police and daughters about what their school may say about hairstyles. “These are conversations that people of color dread this day and age. They wake up trying to parent their inner child and also parent the child who they brought into this world.” He notes that some constituents are actually afraid of having children for these reasons.

A young Black man told Daniels that if he had a choice to be white, he would take it: “I wouldn’t have to worry about my life every time I go to school,” the child suggested, or “an administrator being on my back in school because she’s assuming I’m not doing my work because I don’t care as opposed to me not being able to feed my stomach because I’m hungry.” Daniels said these are real-life situations that young men and single mothers struggle with on a daily basis.

When the federal government recently sent relief stipends, many men of color were left out for not paying child support as if they just didn’t want to pay, when the real reason was they couldn’t afford it.

Growing up as a person of color, you’re taught that you have to be near perfect. You can’t get away with things other populations can, said Daniels. He added: “If someone of color who you’re vetting sends an email with an error, it doesn’t mean they’re incompetent; it probably means they’re doing more than one thing or wearing two hats.” He said he likes funders who offer technical support, as well as authentic conversation, and who don’t avoid the word “racism.”

Giant triplets

Meanwhile, the Quincy Institute, led by retired U.S. Army colonel and noted critic of the Iraq War-turned Boston University professor Andrew Bacevich, held a virtual “Emergency Summit” of public intellectuals to reflect on America Besieged by Racism, Materialism and Militarism—the “giant triplets” identified by Martin Luther King, Jr. in his 1967 speech “Beyond Vietnam.”

Against the backdrop of the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, Bacevich began by asking the panelists how those triplets continue to threaten democracy.

One panelist, New York Times contributing writer Peter Beinart, noted that one of the triplets, materialism, while an enormous cultural problem, might not rank as one of the three main ones today because, unlike in the 1960s when people assumed that American living standards would be going up, many today suffer from a lack of materialism and hold very little hope that their situations will improve.

Militarism and racism, however, do persist. As a foreign-policy term, however, “militarist” has been replaced by euphemisms such as “muscular” or “tough-minded.” But militarism is plain to see in the degree to which domestic policing has been affected by military equipment, and veterans return home without decent healthcare. (As an aside, the military has been lauded for well-run coronavirus vaccine sites while the civilian counterparts are often cast as failures. Asked why this is on a recent television news show, Alex Pareene, a staff writer for The New Republic, offered a simple explanation: The U.S. has never disinvested in the military.)

One panelist, the Rev. Liz Theoharis, who is co-chair with Rev. William Barber, of the Poor People’s Campaign, said she would add to King’s triplets, two more demons: ecological devastation and emboldened religious nationalism evidenced on Jan. 6.

Regarding militarism, Theoharis noted that while there’s no military draft per se, there is a “poverty draft” because for many young people, it’s the only way to put food on their table and get an education. Yet, they come home to a lack of opportunity. The majority of single male adults that are homeless in our society are veterans. The military system is “not about the ideals of a democracy and opportunity and possibility and freedom for all, it’s sending poor people, Black people and Latino people to go and fight and kill poor people in other parts of the world,” she said, noting that the U.S. has military bases in more than 800 places. The coronavirus threat has spread in the fissures that we faced before in terms of racism and inequality, which were already claiming lives before the pandemic.

Neta C. Crawford, a professor and chair of political science at Boston University, said democracy is the antidote to militarism, extreme materialism and racism. Members of Congress are tightly connected to military bases and defense contractors in their districts based on the belief that the military-industrial complex creates good jobs. Crawford said we need break this misconception with solid analysis that shows military spending actually produces fewer jobs and what we could be doing instead.

Daniel McCarthy, editor of Modern Age: A Conservative Review and editor-at-large of The American Conservative, noted the irony that U.S. military adventures abroad are framed as antiracist. When he opposed the Iraq War, he was accused of being against Arab democracy and therefore racist. He lamented that we need to find something for the part of industrial America that has been declining, not necessarily related to militarism but to make things that people want to buy.

Justice and belonging in New England