Bad Lyme disease season on its way

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Physical distancing because of COVID-19 has caused cabin fever to reach an all-time high, and people are seeking solace in the great outdoors. And while physical distancing rules still apply outside, the Rhode Island departments of environmental management and health are hoping that people will add another practice to their outdoor excursions: keeping an eye out for ticks.

With a mild winter in which many more ticks than usual likely survived and with more people expected to be outside this year because of the pandemic, 2020 is shaping up to be a bad year for tick bites and the transmission of Lyme and other diseases, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Rhode Island already has the fifth-highest rate of Lyme disease in the country, with 1,111 people diagnosed in 2018.

To help mitigate this problem, DEM and the Department of Health are again promoting the state’s Tick Free Rhode Island campaign.

“At a time when the COVID-19 crisis has forced us into closing state parks and campgrounds, it might seem incongruous to sound the alarm about Lyme disease,” DEM Director Janet Coit said. “Yet, Lyme is a very dangerous disease. So, all of us, whether we’re taking a walk around the block, spending time in our backyards, or going fishing, should do our best to prevent tick bites along with respecting social distancing norms.”

Here are the agencies’ three keys to tick safety:

Repel. Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaves. If you are going to be in a wooded area, walk in the center of the trail to avoid contact with overgrown grass, brush, and leaves at the edges. Wear long pants and long sleeves. Tuck your pants into your socks. Wear light-colored clothes so you can see ticks more easily.

Check. Take a shower after you come back inside from a wooded area. Do a full-body tick check in the mirror; parents should check their kids for ticks and pay special attention to the area in and around the ears, in the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and in their hair. Keep an eye on you pets as well, as they can bring ticks into the house.

Remove. If possible, use tweezers to remove a tick; grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible and pull straight up. If you don’t have tweezers, use a tissue or gloves. Keep an eye on the tick bite spot for signs of rash, or symptoms such as fever and headache.

Most people who get Lyme disease get a rash anywhere on their body, though it may not appear until long after the tick bite. At first, the rash looks like a red circle, but as the circle gets bigger, the middle changes color and seems to clear, so the rash looks like a target bull’s-eye.

Some people don’t get a rash, but feel sick, with headaches, fever, body aches, and fatigue. Over time, they could have swelling and pain in their joints and a stiff, sore neck; or they could become forgetful or have trouble paying attention.

Deer ticks in their developmental progression

Tim Faulkner: Projected sea-level rise looks scarier

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A stitch in time saves nine. A cat has nine lives. Baseball legend Ted Williams wore No. 9. Unfortunately for Rhode Island, nine is also the new number for the feet of projected sea-level rise.

Just a few years ago, the upper estimate for sea-level rise was 3 feet. More recently, it was 6.6 feet. But a recent assessment by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projects sea-level rise to increase in Rhode Island by 9 feet, 10 inches by 2100.

“To put in perspective we’ve had 10 inches (of sea-level rise) during the last 90 years. We’re about to have 10 feet in the next 80 years,” said Grover Fugate, executive director of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC).

Fugate made the remarks during a recent environmental business roundtable featuring the state’s top energy and environment officials: Fugate; Janet Coit, executive director of the Department of Environmental Management; and Carol Grant, commissioner of the Office of Energy Resources.

Coit and Grant highlighted the positive trends in Rhode Island's “green economy,” such as growth in renewable energy and the fishing industry. Fugate spoke last and, referring to himself as the “Debbie Downer” of the meeting, straightaway delivered the bad news facing the state from climate change.

“I’ve been director here for 31 years and the numbers we are seeing are staggering to me,” Fugate said of the NOAA report. “The changes we are going to see to our shoreline are profound, dramatic, and there is going to be a lot of economic adjustment going forward."

The major upward revision in sea level-rise projections, he said, will be transformative to life in Rhode Island, particularly along the coastal region of Washington County and much of Bristol County and Warwick.

To drive the point home, Fugate showed photographs of severe beach erosion along Matunuck Beach in South Kingstown. The shoreline there has been eroding at a clip of 4 feet annually since the 1990s. Recently, the rate climbed to 8 feet a year. That level was calculated before NOAA released the latest projected increase in sea-level rise.

Higher seas, Fugate said, create a multiplier effect that intensifies coastal erosion and flooding. Tides and storm surges reach further inland. Climate change also produces stronger wind and rain events. Thus, a storm classified as a 50-year event can cause the same damage as a 100-year event, according to Fugate.

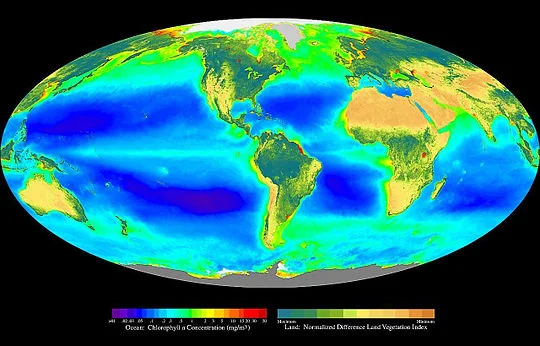

The recent NOAA report says the principal cause for higher seas is the melting of land-based ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. Since 2009, the region from Virginia north to the Canadian Maritime Provinces has experienced accelerated sea-level rise due to changing ocean currents in the Gulf Stream. NOAA expects that trend to continue.

According to the report, the impact of prolonged sea-level rise will be loss of life, damage to infrastructure and the built environment, permanent loss of land, ecological transformation of coastal wetlands and estuaries, and water-quality impairment.

Those impacts, Fugate said, are already here and being felt. He showed slides of storm drains flowing backwards and flooding parking lots during regular high tides, and buildings that are becoming islands. Coit noted that wetlands and marshes are essentially drowning in this higher water.

“The future is here now,” Fugate said. “It’s here and we are seeing profound changes.”

To combat climate change, coastal buildings are being elevated thanks to federal incentives. The CRMC also has permissive policies that allow for the rebuilding of sea walls damaged by these more forceful storms and accelerated erosion.

Several environmental engineers and municipal planners at the recent meeting raised questions about the need for policies and regulations to address threatened infrastructure, such as septic systems, utilities, and spoke about the risk of inland river flooding. Their queries suggested that the state is taking a piecemeal approach to a vast problem.

The environmental group Save The Bay has criticized an Army Corps of Engineers plan to provide funding to elevate homes along the Rhode Island coast from Westerly to Narragansett, R.I. Fugate said that plan has flaws, but endorses the concept as the best solution for protecting property owners.

Save The Bay, however, wants greater consideration given to migration away from the coast. Retreat from a receding shoreline, it argues, protects people, as well as the ecological health and resilience of the natural resource that defines the Ocean State.

“Are we going to elevate homes that can’t be reached because the roads are under water?” asked Topher Hamblett, Save The Bay’s policy director. “I think the state needs a long-term strategy about moving back from the coast.”

Hamblett portended that coastal retreat would greatly impact the real-estate market and present enormous challenges for policymakers and elected officials.

“But this is so big on so many levels that unless and until we start really seriously planning to move back out of harms way, we are going to inflict a lot of otherwise avoidable damage on ourselves,” Hamblett said.

Fugate and Coit said elevating buildings may not be the best option, but it's the only one currently with funding. If approved, it would provide about $60 million of federal relief money apportioned after Hurricane Sandy.

“Yes, the money would be better spent in another way,” Coit said. “Could we protect more land on the shore and in the flood plains? Could we help people move out all together through a buy-out program? Could we look at infrastructure that helps the whole public instead of the individual homeowner?”

Fugate said the problem is compounded by federal flood-insurance maps that created immense controversy in 2013, when the Federal Emergency Management Agency released inaccurate flood-zone maps. Those maps led to astronomically high insurance premiums for some and rampant confusion among others living on or near the water.

Fortunately, Fugate said, the CRMC and the University of Rhode Island have designed interactive maps forecasting the impacts of sea-level rise, coastal flooding and storm surge. The modeling behind those maps is helping remedy the flood-map problem. Nevertheless, Fugate encouraged anyone with property in a flood zone to buy flood insurance.

Coit said the state is in a good position to address sea-level rise and climate change by following the same model that led to the development of the Block Island Wind Farm. The Ocean Special Area Management Plan (Ocean SAMP) brought together federal, local and private stakeholders to craft a plan for mapping out public and private uses for offshore regions. CRMC is working on a similar Shoreline SAMP to address long-term coastal planning.

Coit said the state Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4) is already addressing comprehensive climate-change planning for the state. The EC4 recently released an assessment of Rhode Island's greenhouse gas-emissions reduction plan. It’s now scrutinizing flooding at wastewater treatment facilities, among other threats from climate change.

“I think we are in a good place for Rhode Island to really look holistically at a resiliency and adaptation plan that takes into account all of the issues,” Coit said.

Most of the EC4’s funding comes from the Environmental Protection Agency. CRMC gets half of its budget from the Department of Commerce. But Coit, Grant and Fugate say President Trump’s hostility toward climate change won’t curtail state planning efforts, much less the realities of sea-level rise and global warming.

While the NOAA report doesn’t offer its own solutions, it concludes that sea-level rise is unrelenting.

“Even if society sharply reduces emissions in the coming decades, sea level will most likely continue to rise for centuries,” according to NOAA.

Tim Faulkner writes for ecoRI News.

Tim Faulkner: Trump vs. the biosphere?

The day after Donald Trump’s surprise election win, the mood among environmentalists was, as expected, glum.

During his campaign, Trump, a climate-change denier and fossil-fuel proponent, vowed to withdraw from global climate treaties and neuter the Environmental Protection Agency. All told, his candidacy was considered a colossal threat to the biosphere.

Now that he’s two months away from taking office, it’s mostly guesswork as to which of Trump’s grand proclamations of environmental ruin will become reality.

Nationally, environmentalists expect that, at least, the goal of limiting temperature rise to 2 degrees is a lost cause, as is limiting atmospheric carbon dioxide to less than 400 parts per million.

To deal with their anxiety, environmental groups such as 350.org are encouraging environmentalists to partake in peaceful protesting. The National Resources Defense Council hosted a conference call for the aggrieved Nov. 10 titled “Defending Our Environment from the Trump Presidency.”

The consensus response from local government officials is to embrace autonomy.

“(Trump's win) puts an even greater burden on states to take action and be creative,” Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo said during a Nov. 9 meeting of the Rhode Island climate council.

Raimondo received an update on Rhode Island’s long-term emissions-reduction plan. She and agency and department officials gave no indication of changing course on climate adaptation and mitigation efforts.

Raimondo said it's not known what Trump will do with President Obama’s Climate Action Plan. But Trump’s unexpected victory creates urgency to move forward with local initiatives, she added.

“Norms change in times of crisis, and I do believe we are facing a climate-change crisis, so we do have to get people to take action,” Raimondo said.

The governor confirmed that she isn't changing her neutral-to-favorable position on the proposed fossil-fuel power plant in Burrillville, a project that would be the state’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Janet Coit, director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, told ecoRI News that Trump’s victory was sobering. “It means we have to work all the harder.”

Fortunately, Rhode Island is surrounded by states with shared regional and local environmental goals, Coit said.

If federal support and guidance declines, she said, “Now we have to stop, regroup and guess that the leadership will have to come from the state level. I guess we have to look to ourselves more.”

Ken Payne, chair of state renewable energy committee, as well as food and farm programs, said the election means that progress on these issues will not only have to come from the state, but from communities and neighborhoods. Before the election, he and Brown University Prof. J. Timmons Roberts announced plans to launch a new, non-government affiliated group to advance green initiatives.

Roberts wasn't at the recent climate council meeting; he's in Morocco with students researching the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations.

In an article for Climate Home, he echoed the wait-and-see refrain put forth by environmental experts who wonder if the country and climate policy will be governed by Trump the negotiator or Trump the tyrant.

“So which Trump will govern? There is cause for both hope and fear,” Roberts wrote.

To others, fear caused by the election affirms reality. Morgan Victor of the Pawtucket-based environmental activist group The FANG Collective, said Trump’s win is evidence of American ongoing legacy of colonialism and slavery.

“It’s a reality that white supremacy runs in this country both overtly and covertly,” Victor said.

The Providence resident and member of the Wampanoag tribe participated in the ongoing Standing Rock Sioux pipeline protests taking place in North Dakota.

Having Trump in office will justify more attacks against indigenous groups and their land, Victor said.

“It’s scary. I hope it wakes people up, especially white people, to take care of the ones they love,” she said.

Tim Faulkner writes for ecoRI News.