Poisoned Ivy?

The Harvard Lampoon Building, also known as the Lampoon Castle, in Cambridge. Prepare to see The Lampoon, Harvard College’s humor magazine, take on Harvard’s problems with Congress.

— Photo by Beyond My Ken

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

In Schenck v. United States (1919), U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. famously wrote of free speech that “no one has the right to {falsely} shout ‘fire’ in a crowded theater.’’

What about shouting “kill all the ----"?

There was something creepy about the congressional grandstanding (mostly by Republicans, of course) in grilling the presidents of Harvard, MIT and the University of Pennsylvania about anti-Semitism, alleged and real, on their elite campuses. Of course those leaders’ robotic and evasive, or at least equivocal, responses, crafted by a law firm, didn’t do them any good in facing those on Capitol Hill set on appealing to their always-angry-and-envious base and funders by sticking it to the trio, portrayed as Ivy-covered swells.

The authoritarian-minded inquisitors were basically telling the private universities’ leaders how to run their institutions. But even small colleges, let alone the big elite ones above, are complex enough to be compared to little countries, with sometimes warring constituencies – students, trustees, faculty, funders (including very rich and sometimes arrogant and bossy donors, more and more of whom are oft-amoral hedge fund and private-equity moguls), and residents of the schools’ host communities. These institutions can’t be run as dictatorships.

Further complicating things is that colleges and universities are, more than most other parts of American society, supposed to be dedicated to freedom of speech and inquiry. That’s bound to lead to angry encounters. Finally, universities are increasingly ethnically and otherwise diverse, thus leading to tensions between, say, people of Jewish and Palestinian backgrounds on campuses.

As for speech codes for students: They may make things more toxic by bottling up anger. But I’d leave decisions on codes to each university and its officials’ sense of the danger of violence on their own campuses. And if students don’t like the codes, they can transfer to a school more suitable for their feelings and opinions.

Of course, the threat to yank federal money always hangs over congressional hearings. But we should bear in mind that colleges and universities get federal money for good reasons -- to educate future leaders and other citizens, to underwrite scientific and other research and otherwise enrich society. In short, for the national self-interest.

Thus while I think the three presidents above generally did a bad job in explaining their universities’ evasive “official” positions on confronting anti-Semitism in the current fraught climate, I have some sympathy for them, even if they are trained, as are many leaders dealing with crises, to prevaricate.

Meanwhile, now that Harvard President Claudine Gay has been raked over the coals in Congress, her career in the distant past is being exhumed, raising allegations she’s a plagiarist, and certainly some of her scholarly work has that aroma. So I wouldn’t be surprised if she’s soon no longer leader of America’s richest university. Once you’re in hot water for one problem, you’re apt to find yourself in it for something else as your enemies continue digging.

Random is better

Richard Rummell's 1906 watercolor view of Harvard’s main campus, in Cambridge

The first telephone directory, printed in New Haven, Conn., in November 1878

“I’d rather entrust the government of the United States to the first 400 people listed in the Boston telephone directory than to the faculty of Harvard University.”

William F. Buckley Jr. (1925 -2008), conservative writer and editor

David Warsh: Sachs, Ukraine and the Harvard caper

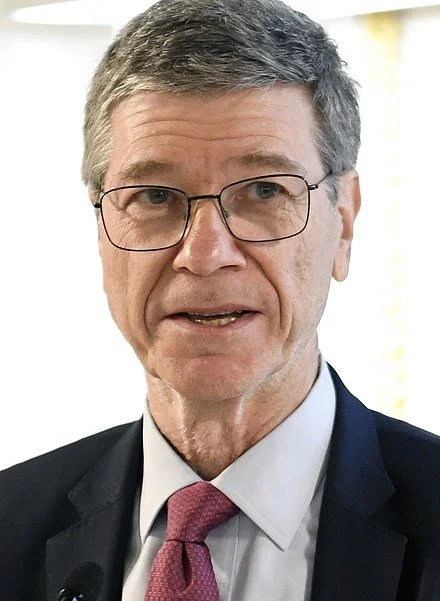

Jeffrey Sachs

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is hard to feel much sympathy for Jack Teixeira, the Air National Guardsman from North Dighton, Mass., who is accused of sharing top-secret U.S. government documents with his obscure online gaming group. It was from there that, predictably, the secrets gradually slipped out into the larger world. Still, the news story that caught my attention was one in which a friend from the original game-group explained to a Washington Post reporter what he understood to have been the 21-year-old guardsman’s motivation.

The friend recalled that Teixeira started sharing classified documents on the Discord server around February 2022, at the beginning of the war in Ukraine, which he saw as a “depressing” battle between “two countries that should have more in common than keeping them apart.” Sharing the classified documents was meant “to educate people who he thought were his friends and could be trusted” free from the propaganda swirling outside, the friend said. The men and boys on the server agreed never to share the documents outside the server, since they might harm U.S. interests.

The opinion of a callow 21-year-old scarcely matters, at least on the surface of it. Discussions will quickly shift to the significance of the leaked information itself. Comparisons will be made of Teixeira’s standing as a witness to government policy, and judge of it, relative to others of similar ilk: Daniel Ellsberg, Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, Julian Assange, and Reality Winner.

But Teixeira’s opinion interested me mainly because it mirrored views increasingly under discussion at all levels of American civil society. I thought immediately, for instance, of Jeffrey Sachs, director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University. Sachs is not widely understood to be involved in the story of the war in Ukraine. But since 2020, and the death of Stephen F. Cohen, of New York University, Sachs has become the leading university-based critic of America’s role in fomenting the war.

On Feb. 21, Sachs appeared before a United Nations session to present a review of the mysteries surrounding the destruction of Russia’s nearly complete Nord Stream 2 pipeline last September. The consequences were “enormous,” he said, before calling attention to an account by independent journalist Seymour Hersh that ascribed the sabotage to a secret American mission authorized by President Biden.

Despite a history of previous investigative-reporting successes (My Lai massacre, Watergate details, Abu Graib prison), Hersh’s somewhat hazily sourced story was not taken up by leading American dailies. In an apparent response to the attention given to Sachs’s endorsement of it, however, national-security sources in Washington and Berlin soon surfaced stories of their investigation of a mysterious yacht, charted from a Polish port, possibly by Ukrainian nationals, that might have carried out the difficult mission. Hersh responded forcefully to the “ghost ship” stories in due course.

Then on Feb. 28, at a time when English-language newspapers were writing about the year since Russia had boldly launched an all-out invasion of Ukraine, Sachs published on his Web site his own version of the story. “The Ninth Anniversary of the Ukraine War’’ is a concise account of Ukrainian politics since 2010. Especially interesting is Sachs’s analysis of U.S. involvement:

During his presidency {of Ukraine} (2010-2014), {Viktor} Yanukovych sought military neutrality, precisely to avoid a civil war or proxy war in Ukraine. This was a very wise and prudent choice for Ukraine, but it stood in the way of the U.S. neoconservative obsession with NATO enlargement. When protests broke out against Yanukovych at the end of 2013 upon the delay of the signing of an accession roadmap with the EU, the United States took the opportunity to escalate the protests into a coup, which culminated in Yanukovych’s overthrow in February 2014.

The US meddled relentlessly and covertly in the protests, urging them onward even as right-wing Ukrainian nationalist paramilitaries entered the scene. US NGOs spent vast sums to finance the protests and the eventual overthrow. This NGO financing has never come to light.

Three people intimately involved in the US effort to overthrow Yanukovych were Victoria Nuland, then the Assistant Secretary of State, now Under-Secretary of State; Jake Sullivan, then the security advisor to VP Joe Biden, and now the US National Security Advisor to President Biden; and VP Biden, now President. Nuland was famously caught on the phone with the US Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, planning the next government in Ukraine, and without allowing any second thoughts by the Europeans (“Fuck the EU,” in Nuland’s crude phrase caught on tape).

So, who is Jeffrey Sachs, anyway, and what does he know? It’s a long story. His Wikipedia entry tell you some of it. What follows is a part of the story Wiki leaves out.

Sachs was born in 1954. Having grown up in Michigan, the son of a labor lawyer and a full-time mother, he graduated from Harvard College in 1976. As a Harvard graduate student, he soon found a rival in Lawrence Summers, the nephew of two Nobel-laureate economists, who had graduated the year before from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Sachs completed his PhD in three years, after being appointed a Junior Fellow, 1978-81. Harvard Prof. Martin Feldstein supervised his dissertation, and, three years later, supervised Summers as well. Both were appointed full professors in 1983, at 28, among the youngest ever to achieve that position at Harvard. Sachs collaborated with economic historian Barry Eichengreen on a famous study of the gold standard and exchange rates during the Great Depression. Summers was elected a Fellow of the Econometric Society in 1985, Sachs the following year.

Summers went to Washington in 1982, to serve for a year in the Council of Economic Advisers under CEA chairman Feldstein; in 1985, Sachs was invite to advise the government of Bolivia on its stabilization program. After success there, he was hired by the government of Poland to do the same thing: he was generally considered to have succeeded. In 1988, Summers advised Michael Dukakis’s presidential campaign; in 1992, he joined Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign. Sachs became director of the Harvard Institute for International Development.

In the early 1990s, Sachs was invited by Boris Yeltsin to advise the government of the soon-to-be-former Soviet Union on its transition to market economy. Here the details are hazy. Clinton was elected in November 1992. During the transfer of power, another young Harvard professor, Andrei Shleifer, was appointed to run a USAID contract awarded to Harvard to formally offer advice, thus elbowing aside Sachs, his titular boss. Shleifer had been born in the Soviet Union, in 1962; arriving with his scientist parents in the US in 1977. As a Harvard sophomore, he met Summers first in 1980, becoming Summers’ protégé, and, later, his best friend.

In 1997, USAID suspended Harvard’s contract, alleging that Shleifer, two of his deputies, and his bond-trader wife, Nancy Zimmerman, had abused their official positions to seek private gain. Specifically, they had become the first to receive a license from their Russian counterparts to enter the Russian mutual fund business, at a critical moment, as Yeltsin campaign for election to a second term. A week later Sachs fired Shleifer, and the project collapsed. Stories in The Wall Street Journal played a key role. And two years later, the U.S. Department of Justice file suit against Harvard and Shleifer, seeking treble damages for breach of contract. All this is describe in Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Enlargement) after Twenty-Five Years, a book I dashed off after 2016 as I was turning my hand from one project to another.

Soon after the government file its suit, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore in the “hanging chad” election of 2000, and a few months after that, Harvard hired former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers as its president. Harvard lost is case in 2004 in 2005, and Summers’s defense under oath of Schleifer’s conduct played a role – who knows how great? – in Summers’s overdetermined decision to resign his presidency in 2006. By then, Sachs had long since decided to leave Harvard. In 2002, after 25 years in Cambridge, he became director of Columbia University’s newly established Earth Institute, uprooting the pediatric practice of his physician wife as part of the move.

Sachs was always reluctant to talk about Harvard’s Russia caper. I haven’t spoken to him in 27 years. At Columbia, he enjoyed four-star rank, both in Manhattan, and in much of the rest of the world, serving for 16 years as a special adviser to the UN’s Secretary General, beginning with Kofi Annan. Time put his book, The End of Poverty,: Economic Possibilities for Our Time, on its cover; Vanity Fair’s Nina Munk published The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty, in 2013; glowing blurbs, from Harvard’s University’s Dani Rodrik and Amartya Sen, attested to his standing in the meliorist wing of the profession. In 2020, Sachs became involved, with a virologist colleague, in the COVID “lab-link” controversy, first on one side, then on the other. His stance on the Ukraine war had earned him plenty of criticism.

Sachs will turn 70 next year. He stepped down from the Earth Institute in 2016. As a university professor at Columbia, he teaches whatever he pleases. He writes mainly on his own web page, where he is always worth reading. But he is spread too thin there to influence more than occasionally the on-going newspaper story of the war. As a life-long dopplegänger to Larry Summers, however, Sachs casts a very long shadow indeed.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Brigid Harrington: As high court decision looms, colleges search for alternatives to affirmative action

At Harvard’s campus, in Cambridge, Mass., the university’s seal.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The U.S. Supreme Court may ban race-based affirmative action for college admissions this year. But that does not mean that schools will abandon their diversity goals.

As administrators wait for the high court to issue its final decision in two key affirmative-action cases, they are figuring out how they can continue to create the heterogenous campuses they want.

It is not an easy task. In an effort to increase racial diversity on campus, many colleges already have experimented with changing early action and legacy rules to no avail. “There is no replacement for being able to consider race,” Olufemi Ogundele, the University of California at Berkeley’s dean of admissions, recently told The Washington Post. “It just does not exist.”

Still, schools are searching for viable alternatives. The justices signaled during oral arguments last fall that they were ready to overturn their 19-year-old ruling that allowed race to be a factor in admissions decisions. Even back in 2003, the court maintained that race was not the ideal way to achieve diversity, saying racial preferences would no longer be necessary within 25 years.

In the two cases currently before the court, Students for Fair Admissions sued Harvard University as well as the University of North Carolina (UNC), arguing that it was unconstitutional to use race as part of the holistic admissions process. The court is expected to issue its ruling in June.

Judicial scholars expect that the court will make no distinction between public and private universities, banning affirmative action for nearly every school. Groups that filed amicus briefs in the current cases argued for two exceptions: for certain faith-basedschools, which say their mission is to help the historically disadvantaged, and for military academies, which contend that diversity in the officer corps is critical for military cohesion. It remains to be seen how, or if, the court will consider such exceptions.

The vast majority of colleges include diversity as part of their mission statements. But they will now need to engage in some deep soul-searching to decide what diversity really means to them. Do they want only students of different races on campus or do they really seek diversity of student viewpoints and life experiences?

To be sure, race – especially in America – influences a person’s life experience, and most colleges would agree that having students interact with classmates from other races in itself is valuable. But there are many other types of diversity, too, and schools may want to balance them all, including cultural, religious, geographic and socio-economic diversity.

Colleges that do not engage in race-based affirmative actions have tried a variety of approaches to achieve diversity based on socioeconomic and other factors. Texas launched an innovative model more than 20 years ago, later adopted by Florida and California schools, that guarantees students admission to its flagship public universities if they graduated in the top 10 percent of their high school classes. This “top 10 percent plan” quickly became controversial and has had mixed results. It boosted Hispanic enrollment at leading public universities, but not Black enrollment, according to an analysis by The Texas Tribune. The law had minimal effects on application rates from low-income high schools, other analyses found.

Another potential approach: ending early admission. These programs are used mostly by affluent students with access to savvy college counseling, who know it’s far easier to get into top-rated schools by applying early. But ending the practice may not make much difference unless a lot of schools agreed to simultaneously make such a change. Harvard University ended early admissions in 2007 for five years, urging other Ivy League schools to join them. But when no other colleges halted their programs, Harvard’s ability to attract historically disadvantaged students plummeted. Top minority students simply chose other Ivy League colleges. After five years, Harvard restarted its early-action program.

In their search for alternatives to race-based affirmative action, some colleges may consider eliminating legacy preference programs. Since the vast majority of legacies are Caucasian, some education experts view this practice as unfair and arcane. Top British universities, such as Oxford and Cambridge, ended legacy admissions long ago in the name of equity, but American university administrators have argued that the number of legacies is so small that it wouldn’t affect diversity much.

Colleges that have ended legacy admissions report vastly different experiences. The University of California schools did not improve their diversity by banning legacy admissions. But Johns Hopkins University, which stopped legacy preferences in 2014, has seen a substantial increase in minority enrollment in recent years. The number of undergraduate minorities jumped by more than 10 percentage points between 2009 and 2020, and now more than one-fourth of the university’s undergraduates are minorities.

There’s one key difference between Hopkins and the University of California schools: affirmative action. Unlike the University of California, Hopkins still considers race as a factor in admissions. If the Supreme Court rules that all colleges – including Hopkins – must be race-blind, it’s not clear whether banning legacy admissions would make much difference.

Some colleges are thinking about focusing on socio-economic diversity rather than race, which could wind up increasing the number of historically-disadvantaged minorities since many such students are low-income. But that could prove tricky, too. Outside of the rarefied world of Harvard and UNC, there are limits to how many students from low-income backgrounds some colleges can admit because of financial constraints. Many simply do not have enough scholarship money to offer to these applicants.

In a race-blind admissions world, colleges may need to resort to asking its applicants for help. If they require a new essay, asking students how they could contribute to diversity on campus, they may discover all kinds of new ways to create the educational melting pot they really want. It may be schools’ best hope.

Brigid Harrington is a lawyer at Bowditch & Dewey LLP a Massachusetts firm. Her practice focuses on issues facing institutions of higher education. Email: bharrington@bowditch.com.

Rachel Bluth: Noise pollution jangles nerves and hurts sleep

Measuring the noise from a leaf blower.

— Photo by fir0002

When there’s a loud noise, the auditory system signals that something is wrong, triggering a fight-or-flight response in the body and flooding it with stress hormones that cause inflammation and can ultimately lead to disease.

— Peter James, an assistant professor of environmental health at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

SACRAMENTO

Mike Thomson’s friends refuse to stay over at his house anymore.

Thomson lives about 50 yards from a busy freeway that bisects California’s capital city, one that has been increasingly used as a speedway for high-speed races, diesel-spewing big rigs, revving motorcycles — and cars that have been illegally modified to make even more noise.

About the only time it quiets down is Saturday night between 3 and 4 a.m., Thomson said.

Otherwise, the din is nearly constant, and most nights, he’s jolted out of sleep five or six times.

“Cars come by and they don’t have mufflers,” said Thomson, 54, who remodels homes for a living. “It’s terrible. I don’t recommend it for anyone.”

Thomson is a victim of noise pollution, which health experts warn is a growing problem that is not confined to our ears, but causes stress-related conditions like anxiety, high blood pressure, and insomnia.

California legislators passed two laws in 2022 aimed at quieting the environment. One directs the California Highway Patrol to test noise-detecting cameras, which may eventually issue automatic tickets for cars that make noise above a certain level. The other forces drivers of illegally modified cars to fix them before they can be re-registered.

“There’s an aspect of our society that likes to be loud and proud,” said state Sen. Anthony Portantino (D-Glendale), author of the noise camera law. “But that shouldn’t infringe on someone else’s health in a public space.”

Most states haven’t addressed the assault on our eardrums. Traffic is a major driver of noise pollution — which disproportionately affects disadvantaged communities — and it’s getting harder to escape the sounds of leaf blowers, construction, and other irritants.

California’s laws will take time and have limited effect, but noise control experts called them a good start. Still, they do nothing to address overhead noise pollution from circling police helicopters, buzzing drones, and other sources, which is the purview of the federal government, said Les Blomberg, executive director of the Noise Pollution Clearinghouse.

In October 2021, the American Public Health Association declared noise a public health hazard. Decades of research links noise pollution with not only sleep disruption, but also a host of chronic conditions such as heart disease, cognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety.

“Despite the breadth and seriousness of its health impacts, noise has not been prioritized as a public health problem for decades,” the declaration says. “The magnitude and seriousness of noise as a public health hazard warrant action.”

When there’s a loud noise, the auditory system signals that something is wrong, triggering a fight-or-flight response in the body and flooding it with stress hormones that cause inflammation and can ultimately lead to disease, said Peter James, an assistant professor of environmental health at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Constant exposure to noise increases the risk of heart disease by 8% and diabetes by 6%, research shows. The European Environment Agency estimated in 2020 that noise exposure causes about 12,000 premature deaths and 48,000 cases of heart disease each year in Western Europe.

While California Highway Patrol officials will spend the next few years researching noise cameras, they acknowledge that noise from street racing and so-called sideshows — where people block off intersections or parking lots to burn out tires or do “doughnuts” — has surged over the past several years and disturbs people right now.

Cars in California are supposed to operate at 95 decibels — a little louder than a leaf blower or lawn mower — or less. But drivers often modify their cars and motorcycles to be louder, such as by installing “whistle tips” on the exhaust system to make noise or removing mufflers.

In 2021, the last full year for which data is available, the highway patrol issued 2,641 tickets to drivers for excessive vehicle noise, nearly double 2018’s 1,400 citations.

“There’s always been an issue with noise coming from exhausts, and it’s gained more attention lately,” said Andrew Poyner, a highway patrol captain. “It’s been steadily increasing over the past several years.”

The American Public Health Association says the federal government should regulate noise in the air, on roads, and in workplaces as an environmental hazard, but that task has mostly been abandoned since the federal Office of Noise Abatement and Control was defunded in 1981 under President Ronald Reagan.

Now the task of quieting communities is mostly up to states and cities. In California, reducing noise is often a byproduct of other environmental policy changes. For instance, the state will ban the sale of noisy gas-powered leaf blowers starting in 2024, a policy aimed primarily at reducing smog-causing emissions.

One of the noise laws approved in California in 2022, AB 2496, will require owners of vehicles that have been ticketed for noise to fix the issue before they can re-register them through the Department of Motor Vehicles. Currently, drivers can pay a fine and keep their illegally modified cars as they are. The law takes effect in 2027.

The other law, SB 1097, directs the highway patrol to recommend a brand of noise-detecting cameras to the legislature by 2025. These cameras, already in use in Paris, New York City, and Knoxville, Tenn., would issue automatic tickets if they detected a car rumbling down the street too loudly.

Originally, the law would have created pilot programs to start testing the cameras in six cities, but lawmakers said they wanted to go slower and approved only the study.

Portantino said he’s frustrated by the delay, especially because the streets of Los Angeles have become almost unbearably loud.

“It’s getting worse,” Portantino said. “People tinker with their cars, and street racing continues to be a problem.”

The state is smart to target the loudest noises initially, the cars and motorcycles that bother people the most, Blomberg said.

“You can make every car coming off the line half as loud as it is right now and it would have very little impact if you don’t deal with all the people taking their mufflers off,” he said. “That outweighs everything.”

Traffic noise doesn’t affect everyone equally. In a 2017 paper, James and colleagues found that nighttime noise levels were higher in low-income communities and those with a large proportion of nonwhite residents.

“We’ve made these conscious or subconscious decisions as a society to put minority-race communities and lower-income communities who have the least amount of political power in areas near highways and airports,” James said.

Elaine Jackson, 62, feels that disparity acutely in her neighborhood, a low-income community in northern Sacramento sandwiched between freeways.

On weekends, sideshows and traffic noise keep her awake. Her nerves are jangled, she loses sleep, her dogs panic, and she generally feels unsafe and forgotten, worried that new development in her neighborhood would just bring more traffic, noise, and air pollution.

Police and lawmakers don’t seem to care, she said, even though she and her neighbors constantly raise their concerns with local officials.

“It’s hard for people to get to sleep at night,” Jackson said. “And that’s a quality-of-life issue.”

Rachel Bluth is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

John O. Harney: An early look at 2022’s college-commencement season in New England

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE.org)

Long before COVID changed everything, NEJHE and NEBHE’s Twitter channel kept a close eye on New England college commencements. “The annual spring descent on New England campuses of distinguished speakers, ranging from Nobel laureates to Pulitzer Prize winners to grassroots miracle-workers, offers a precious reminder of what makes New England higher education higher,” we bragged. “It is a lecture series without equal.”

In the past two pandemic years, we tracked a lot of postponements and virtual commencements on this beat, as well as Olin College of Engineering’s March 2020 “fauxmencement” ceremony right before coronavirus shut down the campus. Some medical schools at the time moved up graduation dates so graduates could join New England’s COVID-fighting health-care workforce. Dr. Anthony Fauci addressed graduates of the College of Holy Cross, his alma mater.

Going virtual meant hard times for some small New England communities where college-commencement days were crucial to local hospitality providers and the economy. Not to be confused with such larger commencement hosts as the Dunkin Donuts Center for Rhode Island College and Providence College and TD Garden for Northeastern University (switched to Fenway Park during COVID).

This year, as we all hope the pandemic is easing, some New England colleges plan to celebrate not only the class of 2022, but also the classes of 2020 and 2021—for the most part, in person.

Many years, we would pay special attention to the first few announcements of the season. When there was a season. Generally it was spring in the old days. But today’s nontraditional student pursing higher ed on a nontraditional academic calendar might just as easily graduate in January … or any other time for the matter.

As with other stubborn aspects of higher ed, the richest institutions often announced the heavy hitters, though sleepers at quieter places add special value too (think Paul Krugman at Bard College at Simon’s Rock or Rue Mapp at Unity College).

Harvard University, for its part, announced that the principal speaker at its 369th commencement, on May 26, would be New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. Not a bad pick. Ardern has been lauded for her work on climate change and gender equality and, lately on how she has guided New Zealand through COVID. Harvard noted she will be “the 17th sitting world leader to deliver the address.”

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

David Warsh: Goldin's marriage manual for the next generation

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

For many people, the COVID-19 pandemic has been an eighteen-month interruption. Survive it, and get back to work. For those born after 1979, it may prove to have been a new beginning. Women and men born in the 21st Century may have found themselves beginning their lives together in the midst of yet another historic turning point.

That’s the argument that Claudia Goldin advances in Career and Family: Women’s Century-long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021). As a reader who has been engaged as a practitioner in both career and family for many years, I aver that this is no ordinary book. What does greedy work have to do with it? And why is the work “greedy,” instead of “demanding” or “important?” Good question, but that is getting ahead of the story.

Goldin, a distinguished historian of the role of women in the American economy, begins her account in 1963, when Betty Friedan wrote a book about college-educated women who were frustrated as stay-at-home moms. Their problem, Friedan wrote, “has no name.” The Feminine Mystique caught the beginnings of a second wave of feminism that continues with puissant force today. Meanwhile, Goldin continues, a new “problem with no name” has arisen:

Now, more than ever, couples of all stripes are struggling to balance employment and family, their work lives and home lives. As a nation, we are collectively waking up to the importance of caregiving, to its value, for the present and future generations. We are starting to fully realize its cost in terms of lost income, flattened careers, and trade-offs between couples (heterosexual and same sex), as well as the particularly strenuous demands on single mothers and fathers. These realizations predated the pandemic but have been brought into sharp focus by it.

A University of Chicago-trained economist; the first woman tenured by Harvard’s economics department; author of five important books, including, with her partner, Harvard labor economist Lawrence Katz, The Race between Education and Technology (Harvard Belknap, 2010); recipient of an impressive garland of honors, among them the Nemmers award in economics; a former president of the American Economic Association: Goldin has written a chatty, readable sequel to Friedan, destined itself to become a paperback best-seller – all the more persuasive because it is rooted in the work of hundreds of other labor economists and economic historians over the years. Granted, Goldin is expert in the history of gender only in the United States; other nations will compile stories of their own. .

To begin with, Goldin distinguishes among the experiences of five roughly-defined generations of college-educated American women since the beginning of the twentieth century. Each cohort merits a chapter. The experiences of gay women were especially hard to pin down over the years, given changing norms.

In “Passing the Baton,” Goldin characterizes the first group, women born between 1878-97, as having had to choose between raising families and pursuing careers. Even the briefest biographies of the lives culled from Notable American Women make interesting reading: Jeannette Rankin, Helen Keller, Margaret Sanger, Katharine McCormick, Pearl Buck, Katharine White, Sadie Alexander, Frances Perkins. But most of that first generation of college women never became more prominent than as presidents of the League of Women Voters or the Garden Club. They were mothers and grandmothers the rest of their lives.

In “A Fork in the Road,” her account of the generation born between 1898 and 1923, Goldin dwells on 75-year-old Margaret Reid, whom she frequently passed at the library as a graduate student at Chicago, where Reid had earned a Ph.D. in in economics in 1934. (They never spoke; Goldin, a student of Robert Fogel, was working on slavery then.) Otherwise, this second generation was dominated by a pattern of jobs, then family. The notable of this generation tend to be actresses – Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Rosalind Russell, Barbara Stanwyck – sometimes playing roles modeled on real-world careers, as when Hepburn played a world-roving journalist resembling Dorothy Thompson in Woman of the Year.

In “The Bridge Group,” Goldin discusses the generation born between 1924-1943, who raised families first and then found jobs – or didn’t find jobs. She begins by describing what it was like to read Mary McCarthy’s novel, The Group (in a paper-bag cover), as a 17-year-old commuting from home in East Queens to a summer job in Greenwich Village. It was a glimpse of her parents’ lives – the dark cloud of the Great Depression that hung over w US in the Thirties, the hiring bars and marriage bar that turned college-educated women out of the work-force at the first hint of second income.

“The Crossroads with Betty Friedan” is about the Fifties and the television shows, such as I Love Lucy, The Honeymooners, Leave It to Beaver and Father Knows Best that, amid other provocations, led Betty Friedan to famously ask, “Is that all there is?” Between the college graduation class of 1957 and the class of 1961, Goldin finds, in an enormous survey by the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Labor Department, an inflection point. The winds shift, the mood changes. Women in small numbers begin to return to careers after their children are grown: Jeane Kirkpatrick, Erma Bombeck, Phyllis Schafly, Janet Napolitano and Goldin’s own mother, who became a successful elementary school principal. Friedan had been right, looking backwards, Goldin concludes, but wrong about what was about to happen.

In “The Quiet Revolution,” members of the generation born between 1944-1957 set out to pursue careers and then, perhaps, form families. The going is hard but they keep at it. The scene is set with a gag from the Mary Tyler Moore Show in 1972. Mary is leaving her childhood home with her father, on her way to her job as a television news reporter. He mother calls out, “Remember to take your pill, dear.” Father and daughter both reply, “I will.” Father scowls an embarrassed double-take. The show’s theme song concludes, “You’re going to make it after all.” The far-reaching consequences of the advent of dependable birth control for women’s new choices are thoroughly explored. This is, after all, Goldin’s own generation.

“Assisting the Revolution,” about the generation born between1958-78, is introduced by a recitation of the various roles played by Saturday Night Live star Tina Fey – comedian, actor, writer. Group Five had an easier time of it. They were admitted in increasing numbers to professional and graduate schools. They achieved parity with men in colleges and surpassed them in numbers. They threw themselves into careers. “But they had learned from their Group Four older sisters that the path to career must leave room for family, as deferral could lead to no children,” Golden writes. So they married more carefully and earlier, chose softer career paths, or froze their eggs. Life had become more complicated.

In her final chapters – “Mind the Gap,” “The Lawyer and the Pharmacist” and “On Call” – Goldin tackles the knotty problem. The gender earnings gap has persisted over fifty years, despite the enormous changes that have taken place. She explores the many different possible explanations, before concluding that the difference stems from the need in two-career families for flexibility – and the decision, most often by women, to be on-call, ready to leave the office for home. Children get sick, pipes break, school close for vacation, the baby-sitter leaves town.

The good news is that the terms of relationships are negotiable, not between equity-seeking partners, but with their employers as well. The offer of parental leave for fathers is only the most obvious example. Professional firms in many industries are addicted to the charrette – a furious round of last-minute collaborative work or competition to meet a deadline. Such customs can be given a name and reduced. Firms need to make a profit, it is true, but the name of the beast, the eighty-hour week, is “greedy work.”

It is up the members of the sixth group, their spouses and employers, to further work out the terms of this deal. The most intimate discussions in the way ahear will occur within and among families. Then come board rooms, labor negotiations, mass media, social media, and politics. Even in its hardcover edition, Career and Family is a bargain. I am going home to start to assemble another photograph album – grandparents, parents, sibs, girlfriends, wife, children, and grandchildren – this one to be an annotated family album.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

A "Wife Wanted" ad in an 1801 newspaper

"N.B." means "note well".

Alternate ways of seeing

Movie poster for Timothy Leary's Dead

“Women who seek equality with men lack ambition.’’

— Timothy Leary (1920-1996, the Springfield, Mass.-born American psychologist and writer known for his strong advocacy of psychedelic drugs.

As a clinical psychologist at Harvard University, Leary worked on LSD and mushroom studies, resulting in the Concord Prison Experiment and the Marsh Chapel Experiment. The scientific legitimacy and ethics of his research were questioned by other Harvard faculty because he took psychedelics along with research subjects and pressured students to join in. Harvard fired him in 1963.

After that, he continued to publicly promote the use of psychedelic drugs and became a famous figure of the counterculture of the 1960s and after. He popularized such catchphrases as "turn on, tune in, drop out", "set and setting” and "think for yourself and question authority".

He spent much time in jail and on the lecture circuit before dying of prostate cancer in California.

Of Harvard, Summers, Russia and the future

The Kremlin

— Photo by A.Savin

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Some years ago, I set out to write a little book about Harvard University’s USAID project to teach market manners to Boris Yeltsin’s Russian government in the 1990s. The project collapsed after leaders of the Harvard mission were caught seeking to line their own pockets by gaining control of an American firm they had brought in to advise the Russians. Project director Andrei Shleifer was a Harvard professor. His best friend, Lawrence Summers, was U.S. assistant Treasury secretary at the time.

There was justice to be served. The USAID officer who blew the whistle, Janet Ballantyne, was a Foreign Service hero. The victim of the squeeze, John Keffer, of Portland, Maine, was an exemplary American businessman, high-minded and resourceful.

But I had something besides history in mind. By adding a chapter to David McClintick’s classic story of the scandal, “How Harvard Lost Russia,’’ in Institutional Investor magazine in 2006), I aimed to make it more complicated for former Treasury Secretary Summers, of Harvard University, to return to a policy job in a Hillary Rodham Clinton administration.

It turned out there was no third Clinton administration. My account, “Because They Could, ‘‘ appeared in 2018. So I was gratified last August when, with the presidential election underway, Summers told an interviewer at the Aspen Security Forum that “My time in government is behind me and my time as a free speaker is ahead of me.” Plenty of progressive Democrats had objected to Summers as well.

Writing about Russia in the1990s meant delving deeper into the history of U.S.-Russia relations than I had before. I developed the conviction that, during the quarter century after the end of the Cold War, U.S. policy toward Russia had been imperious and cavalier.

By 1999, Yeltsin was already deeply upset by NATO expansion. The man he chose to succeed him was Vladimir Putin. It wasn’t difficult to follow the story Through Putin’s eyes. He was realistic to begin with, and, after 9/11, hopeful (Putin was the among the first foreign leaders to offer assistance to President George W. Bush).

But NATO’s 2002 invitation to the Baltic states — Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — all former Soviet Republics, the U.S .invasion of Iraq, the Bush administration’s supposed failure to share intelligence about the siege of a school in Beslan, Russia, led to Putin’s 2007 Munich speech, in which he complained of America’s “almost uncontained hyper use of force in international relations.”

Then came the Arab Spring. NATO’s intervention in Libya, ending in the death of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, was followed by Putin’s decision to reassume the Russian presidency, displacing his hand-picked, Dimitri Medvedev, in 2012. Putin blamed Hillary Clinton for disparaging his campaign.

And in March 2014, Putin’s plans to further a Eurasian Union via closer economic ties with Ukraine having fallen through, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych fled to Moscow in the face of massive of pro-European Union demonstrations in Kyiv’s Maidan Square. Russia seized and annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula soon after that.

The Trump administration brought a Charlie Chaplin interlude to Russian-American relations. Putin saw no problem: He offered to begin negotiating an anti-hacking treaty right away. Neither did Trump: Remember Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s Oval Office drop-by, the day after the president fired FBI Director James Comey?

Only the editorial board of The Wall Street Journal, among the writers I read, seemed to think there was nothing to worry about in Trump’s ties to Russia. Meanwhile, Putin rewrote the Russian Constitution once again, giving himself the opportunity to serve until 2036, when he will be 84.

But Russia’s internal history has taken a darker turn with the return of Alexander Navalny to Moscow. The Kremlin critic maintains that Putin sought his murder in August, using a Soviet-era chemical nerve-agent. Navalny survived, and spent five months under medical care in Germany before returning.

Official Russian media describe Navalny as a “blogger,” when he is in fact Russia’s opposition leader. He has been sentenced to at least two-and-a-half years in prison on a flimsy charge, and face other indictments. But his arrest sparked the largest demonstrations across Russia since the final demise of the Soviet Union. More than 10,000 persons have been detained, in a hundred cities across Russia, according to Robyn Dixon, of The Washington Post. Putin’s approval ratings stand at 29 percent

What can President Biden do? Very little. However much Americans may wish that Russian leaders shared their view of human rights, it should be clear by now there is no alternative but to deplore, to recognize Russian sovereignty, to encourage its legitimate business interests, discourage its trickery, and otherwise hope for the best. There are plenty of problems to work on at home.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this columnist first appeared.

New study says mask-wearing most important factor in cutting chance of getting COVID-19 during air travel

A Delta Airlines plane being disinfected between flights

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“Researchers at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health have completed a comprehensive, gate-to-gate study on how to greatly reduce the chances of COVID-19 transmission during air travel.

“The study concludes that universal mask-wearing, rigorous cleaning protocols and high-end air filtration systems lower the risk of COVID-19 transmission to minimal levels. The study found that mask-wearing among passengers and crew is the most important factor in reducing risk during air travel. The researchers also found that the use of high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters is extremely effective in removing harmful airborne particles. Ultimately, diligently engaging in this multi-layered approach results in a substantially lowered risk of COVID-19 transmission during air travel in comparison to other activities.

“‘The risk of COVID-19 transmission onboard aircraft [is] below that of other routine activities during the pandemic, such as grocery shopping or eating out,’ the Harvard researchers concluded. 'Implementing these layered risk mitigation strategies…requires passenger and airline compliance [but] will help to ensure that air travel is as safe or substantially safer than the routine activities people undertake during these times.’

“Read more from the National Preparedness Initiative report.’’

Foreign students are a boon for New England

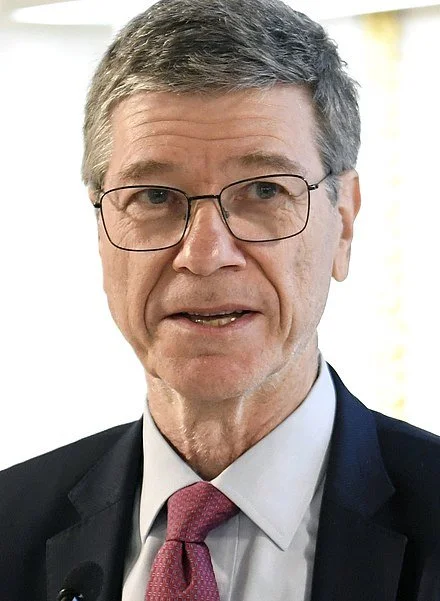

Harvard Square

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It was good news that the Trump administration has rescinded an order that would have stripped visas from foreign students whose courses are moved exclusively online because of the pandemic. Various institutions, led by Harvard and MIT, had sued to block the order, which seemed to many to be obviously illegal. There are hundreds of thousands of such students in America, with tens of thousands in New England.

Trump pushed the visa ban, which would have caused administrative and financial chaos, to try to force colleges and universities to reopen all in-person courses despite the raging pandemic, presumably because he thought that it would be a signal that things were returning to normal, thus boosting the pre-election economy? And he doesn’t like immigrants anyway.

Foreign students are particularly important in New England – economically and otherwise – because of the region’s world-famed colleges and universities. They bring a lot of energy, ambition and a hefty work ethic and help connect us with, and teach us about, the rest of the world. That makes our region more competitive. And some of the best stay and become Americans. Look at all the foreign-born health-care professionals dealing with COVID-19 and the large number of foreigners who have stayed in New England to create successful, high-paying companies based here, most notably in technology.

.

How to tell COVID-19 symptoms

A new guide from Harvard University helps providers differentiate common COVID-19 symptoms—such as shortness of breath and fever—from other symptoms to help health-care workers avoid false negatives.

This could be very useful indeed!

Hit this link to read The Boston Globe’s story.

As with medical matters in general, New England is a world center of research and treatment of COVID-19. Of course, Greater Boston and Connecticut are among the hardest hit by the disease.

The Harvard Medical School quadrangle, in the Longwood Medical Area, in Boston.

Photo by SBAmin

Phil Galewitz: Harvard study sees social distancing maybe extending into 2022

Contemporary engraving of Marseille during the Great Plague of Marseilles in 1720–1721

As New York, California and other states begin to see their numbers of new COVID-19 cases level off or even slip, it might appear as if we’re nearing the end of the pandemic.

President Donald Trump and some governors have pointed to the slowdown as an indication that the day has come for reopening the country. “Our experts say the curve has flattened and the peak in new cases is behind us,” Trump said Thursday in announcing the administration’s guidance to states about how to begin easing social distancing measures and stay-at home orders.

But with the national toll of coronavirus deaths climbing each day and an ongoing scarcity of testing, health experts warn that the country is nowhere near “that day.” Indeed, a study released this week by Harvard scientists suggests that without an effective treatment or vaccine, social distancing measures may have to stay in place into 2022.

Kaiser Health News spoke to several disease detectives about what reaching the peak level of cases means and under what conditions people can go back to work and school without fear of getting infected. Here’s what they said.

It’s Hard To See The Peak

Health experts say not to expect a single peak day — when new cases reach their highest level — to determine when the tide has turned. As with any disease, the numbers need to decline for at least a week to discern any real trend. Some health experts say two weeks because that would give a better view of how widely the disease is still spreading. It typically takes people that long to show signs of infection after being exposed to the virus.

But getting a true reading of the number of cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, is tricky because of the lack of testing in many places, particularly among people under age 65 and those without symptoms.

Another factor is that states and counties will hit peaks at different times based on how quickly they instituted stay-at-home orders or other social distancing rules.

“We are a story of multiple epidemics, and the experience in the Northeast is quite different than on the West Coast,” said Esther Chernak, director of the Center for Public Health Readiness and Communication at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

Also making it hard to determine the peak is the success in some areas of “flattening the curve” of new cases. The widespread efforts at social distancing were designed to help avoid a dramatic spike in the number of people contracting the virus. But that can result instead in a flat rate that may remain high for weeks.

“The flatter the curve, the harder to identify the peak,” said William Miller, a professor of epidemiology at Ohio State University.

The Peak Does Not Mean The Pandemic Is Nearly Over

Lowering the number of new cases is important, but it doesn’t mean the virus is disappearing. It suggests instead that social distancing has slowed the spread of the disease and elongated the course of the pandemic, said Pia MacDonald, an infectious disease expert at RTI International, a nonprofit research institute in North Carolina. The “flatten the curve” strategy was designed to help lessen the surge of patients so the health care system would have more time to build capacity, discover better treatments and eventually come up with a vaccine.

Getting past peak is important, Chernak said, but only if it leads to a relatively low number of new cases.

“This absolutely does not mean the pandemic is nearing an end,” MacDonald said. “Once you get past the peak, it’s not over until it’s over. It’s just the starting time for the rest of the response.”

What Comes Next Depends On Readiness

Although Trump said the nation has passed the peak of new cases, health experts cautioned that from a scientific perspective that won’t be clear until until there is a consistent decline in the number of new cases — which is not true now nationally or in many large states.

“We are at the plateau of the curve in many states,” said Dr. Ricardo Izurieta, an infectious disease specialist at the University of South Florida. “We have to make sure we see a decline in cases before we can see a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Even after the peak, many people are susceptible.

“The only way to stop the spread of the disease is to reduce human contact,” Chernak said. “The good news is having people stay home is working, but it’s been brutal on people and on society and on the economy.”

Before allowing people to gather in groups, more testing needs to be done, people who are infected need to be quarantined, and their contacts must be tracked down and isolated for two weeks, she said, but added: “We don’t seem to have a national strategy to achieve this.”

“Before any public health interventions are relaxed, we better be ready to test every single person for COVID,” MacDonald said.

In addition, she said, city and county health departments lack staffing to contact people who have been near those who are infected to get them to isolate. The tools “needed to lift up the social distancing we do not have ready to go,” MacDonald said.

You’re Going To Need Masks A Long Time

Whether people can go back out to resume daily activities will depend on their individual risk of infection.

While some states say they will work together to determine how and when to ease social distancing standards to restart the economy, Chernak said a more national plan will be needed, especially given Americans’ desire to travel within the country.

“Without aggressive testing and contact tracing, people will still be at risk when going out,” she said. Social gatherings will be limited to a few people, and wearing masks in public will likely remain necessary.

She said major changes will be necessary in nursing home operations to reduce the spread of disease because the elderly are at the highest risk of complications from COVID-19.

Miller said it’s likely another surge of COVID-19 cases could occur after social distancing measures are loosened.

“How big that will be depends on how long you wait from a public health perspective [to relax preventative measures]. The longer you wait is better, but the economy is worse off.”

The experts pointed to the 1918 pandemic of flu, which infected a quarter of the world’s population and killed 50 million people. Months after the first surge, there were several spikes in cases, with the second surge being the deadliest.

“If we pull off the public health measures too early, the virus is still circulating and can infect more people,” said Dr. Howard Markel, professor of the history of medicine at the University of Michigan. “We want that circulation to be among as few people as possible. So when new cases do erupt, the public health departments can test and isolate people.”

The Harvard researchers, in their article this week in the journal Science, said their model suggested that a resurgence of the virus “could occur as late as 2025 even after a prolonged period of apparent elimination.”

Will School Bells Ring In The Fall?

Experts say there is no one-size-fits-all approach to when office buildings can reopen, schools can restart and large public gatherings can resume.

The decision on whether to send youngsters back to school is key. While children have been hospitalized or killed by the virus much less frequently than adults, they are not immune. They may be carriers who can infect their parents. There are also questions of whether older teachers will be at increased risk being around dozens of students each day, MacDonald said.

Another factor: The virus is likely to re-erupt next winter, similar to what happens with the flu, said Jerne Shapiro, a lecturer in the University of Florida Department of Epidemiology.

Without a vaccine, people’s risk doesn’t change, she said.

“Someone who is susceptible now is susceptible in the future,” Shapiro said.

Experts doubt large festivals, concerts and baseball games will happen in the months ahead. California Gov. Gavin Newsom endorsed that view Tuesday, telling reporters that large-scale events are “not in the cards.”

“It’s safe to say it will be a long time until we see mass gatherings,” MacDonald said.

Phil Galewitz is a Kaiser Health News journalist (pgalewitz@kff.org, @philgalewitz)

Harvard launches joins program to help first responders

— Photo by Nikkigee3312

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

The T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University has partnered with Thrive Global and Creative Artists Agency to launch #FirstRespondersFirst, an initiative to support first responders as they combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

The effort seeks to provide first responder healthcare workers with physical and psychological resources during a time when the nation depends upon them. Donations to the fund will be used to provide protective equipment needed by these workers, as well as to provide services—such as childcare, mental health counseling, and virtual workshops—that will help these workers manage their own health while caring for others. Working with public and private sector partners including the Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers, the Conference of Boston Teaching Hospitals, and the Massachusetts Department of Health and Human Services, the initiative is mobilizing local and national groups at multiple levels to support first responders with the resources they need to care for themselves and others.

“As this crisis continues to unfold, it’s important for those on the frontlines to be fortified with essential equipment while being supported to care for themselves. Doing so will allow frontline healthcare workers to be more effective, more resilient and have more of an impact when we all take these proactive steps,” said Michelle Williams, dean of the Harvard Chan School. “We must remember that in this time of crisis, the results of these steps are measured in lives saved.”

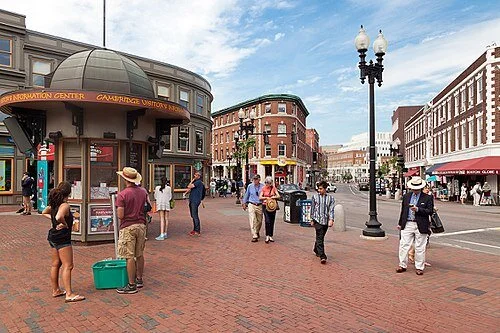

Harvardians at the trough

Drawing by F.G. Attwood for the Harvard Lampoon (1877): "Manners And Customs Of Ye Harvard Studente". Wrote Donald Harnish Fleming: "If you are stuck with a friend or relative who wants to see the sights of Cambridge ... treat him to a view of the animals feeding in Mem. Hall."

Emily P. Crowley/Robert M. Kaitz: N.E. colleges must consider labor laws in the pandemic

College lecture halls are now empty.

— Photo by ChristianSchd

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

As COVID-19 rapidly changes the economic landscape throughout the country, higher education institutions (HEIs) are facing new, constantly evolving challenges. To address these challenges, federal and state governments are quickly drafting laws and regulations that are impacting colleges and universities, and their employees.

Wage and hour challenges

As HEIs grapple with COVID-19 fallout, including the cancellation of in-person courses, commencements, freshman orientations and other events in the upcoming months, they must remain cognizant of existing wage and hour laws when rolling out reductions in hours or furloughs for employees due to the diminished workload. Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), employers need to pay only non-exempt, hourly employees for actual time worked, rather than for time employees are regularly scheduled to work. As a result, reduced-hour schedules or unpaid furloughs are relatively straightforward for these employees, with institutions obligated to compensate them for all hours worked, and nothing beyond that. Perhaps due to public relations concerns, some HEIs have gone beyond their obligations by continuing to pay employees who can neither come to work nor work remotely. Harvard initially offered full pay and benefits for 30 days to direct employees who could not work in light of the campus closure. But in the face of a social media campaign and other negative press, Harvard agreed to provide paid leave and benefits through May 28, 2020, to all direct employees, plus subcontractors. Many schools have enacted similar policies.

Unlike hourly, non-exempt employees, a reduction in hours or furlough may have significant ramifications for exempt, salaried employees. The FLSA exempts these “white collar” salaried employees from overtime premium pay, as their salary is considered remuneration for all hours worked in a week, whether more or less than 40 hours. As a result, employers must pay exempt employees their full week’s salary if they perform any work during that workweek, including work from home. This remains true even while an employee is on furlough, so colleges and universities must communicate clearly to all exempt employees that they cannot perform any work while on furlough—even small tasks like sending work emails—without prior written approval of a supervisor, because any such work would trigger the employer’s obligation to pay that employee a full week’s salary. Where an exempt employee is not furloughed but is working a reduced schedule, employers should be aware that if the reduction in hours causes the employee’s salary to fall below $684 per week, the employee will lose their exemption from overtime premium pay under the FLSA.

Higher education institutions must also consider two other wage and hour requirements. First, any reduction in compensation must only apply prospectively, and employers should give affected employees notice of the impending reduction, in writing. Second, under Massachusetts law, employers must pay furloughed employees all wages owed on the date the furlough is announced, including accrued, unused vacation time. However, the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office has stated that furloughed employees can defer their accrued, unused vacation time until after the furlough ends. Any such deferral agreement should be obtained in writing. Other New England states may have similar payment obligations when furlough is announced.

Families First Coronavirus Response Act

On March 18, 2020, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which took effect on April 1. The act’s two provisions relevant to employers pertain to paid sick time (PST) and Emergency Family and Medical Leave (EFML). Private employers with fewer than 500 employees and public employers of any size must provide PST and EFML. Employers will receive dollar-for-dollar federal tax credits for the PST and EFML benefits they pay.

The act requires covered employers to provide 80 hours of PST to an employee unable to work due to:

COVID-19 symptoms and seeking a medical diagnosis;

an order from a government entity or advice from a healthcare provider to self-quarantine or isolate because of COVID-19; or

an obligation to care for an individual experiencing COVID-19 symptoms or a minor child whose school or childcare service is closed due to COVID-19.

The employee’s reason for taking PST will determine their rate of pay during leave. Employees are eligible for PST regardless of how long they have been on payroll.

Covered employers must also provide up to 12 weeks of job-protected EFML to all employees on payroll for at least 30 days who are unable to work because their minor child’s school or childcare service is closed due to COVID-19. The first 10 days of EFML are unpaid, though an employee may use PST during this period. Eligible employees are thereafter entitled to two-thirds of their regular rate for up to 10 weeks, based on the number of hours they would otherwise be scheduled to work. However, the act caps EFML benefits at $200 daily and $10,000 total, per employee.

Notably, the act contains a broad, discretionary exclusion from PST and EFML coverage for healthcare providers, which may affect higher education institutions. “Health care provider” is defined under the act as any employee of various types of medical facilities, including a postsecondary educational “institution offering health instruction,” a “medical school” and “any facility that performs laboratory or medical testing.” This provision, which forthcoming regulations will likely clarify, ostensibly means that an institution that performs medical research or offers classes in healthcare may exclude any employees from PST and EFML benefits.

Emergency expansion of Mass. unemployment insurance

Employees subject to a furlough or reduction in hours may qualify to take advantage of expanded unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. Massachusetts, for example, has waived the usual one-week waiting period for UI benefits, allowing Massachusetts employees affected by COVID-19 (including those permanently laid off) to collect benefits immediately.

The Massachusetts Department of Unemployment Assistance (DUA) has also published emergency regulations to address the onslaught of new UI claims and provide more flexibility for prompt financial assistance to employees affected by COVID-19. All employees who temporarily lose their jobs due to COVID-19 are deemed to be on “standby status” and are eligible for UI benefits, provided they meet certain criteria. A claimant is on “standby” if he or she “is temporarily unemployed because of a lack of work due to COVID-19, with an expected return-to-work date.” The claimant must:

take reasonable measures to maintain contact with the employer; and

be available for all hours of suitable work offered by the claimant’s employer.

The DUA will contact employers to verify its employees are on standby status and ask for an expected return date. An employer can request that an employee go on standby status for up to eight weeks, or longer, if the business is anticipated to close or have operations severely curtailed for longer than eight weeks and the DUA deems the requested time period reasonable.

Other New England states have likewise implemented similar emergency regulations to ease the burden on employees who have been furloughed, subject to a schedule reduction, or otherwise affected by COVID-19. For example, Maine enacted emergency legislation with many of the same provisions as the Massachusetts emergency UI expansion, but went an extra step in extending UI eligibility to employees on a temporary leave of absence due to a quarantine or isolation restriction, a demonstrated risk of exposure or infection or the need to care for a dependent family member because of the virus.

Federal and state lawmakers are considering additional legislation to address the workplace ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic and will likely continue to do so as new and unanticipated challenges develop. HEIs should actively monitor recent developments and speak with counsel as needed to discuss the impact of additional legislation on their workplaces.

Emily P. Crowley and Robert M. Kaitz are employment and trial attorneys at the Boston law firm of Davis Malm.

Raking it in at Harvard, Yale, etc.

The Harvard seal

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal24.com

Consider the FBI’s arrest of Charles Lieber, chairman of Harvard University’s Chemistry Department, on charges of making false statements to the Defense Department and to Harvard investigators about his hugely lucrative participation in China's Thousand Talents Program, created by the Chinese government to strengthen China's scientific competitiveness. It’s a reminder of how much the Second Gilded Age money culture has infected academia. With multimillion-dollar payouts to football and basketball coaches and university presidents and huge paydays via outside contracts to professors in the sciences, engineering and business faculties, what had been a calling has been turned too often into a business, instead of a “vocation,’’ in this “nonprofit’’ sector.

And now the U.S. Department of Education is investigating Harvard, Yale and other elite universities for failing to disclose hundreds of millions of dollars in gifts and contracts from foreign donors. How much of this is an honest probe and how much is politically instigated by the fact that most of the leaders of these institutions and their professors oppose the Trump regime is unknown.

For more on Professor Lieber, please hit this link.

Plant a forest first?

In Allston, Park Vale Avenue looking toward Brighton Avenue

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Joan Wickersham writes in The Boston Globe: “I remembered how, ten years ago, the great Italian architect Renzo Piano told me about a proposal he had made to the university, that they begin by planting trees, enough trees to turn this land {hundreds of acres in Boston’s Allston neighborhood} into an urban forest. The trees would have created a healthy natural ecosystem, with its own cooling and flood controls. My point is not to pick on Harvard’s current planning. The Allston land will eventually be filled with high-performance hard-working buildings.’’

“But I am wistful about that forest that never happened, which would have created an environment in which the buildings wouldn’t have had to work so hard. Piano’s visionary question was not just ‘What should we put on this land?’ but rather ‘What kind of land should this be?’”

An interesting idea – start a development with the vegetation and landscaping, then fit in the buildings.

To read Ms. Wickersham’s column, please hit this link.

Why Harvard's weird take on Asian-American applicants?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

U.S. District Judge Allison Burroughs has ruled that Harvard’s admissions process doesn’t discriminate against Asian-American applicants, though, she wrote, the university could improve the process with more training and oversight.

But a mystery: Judge Burroughs noted that Asian-American applicants generally got lower ratings on such qualities as integrity, fortitude and empathy. How would Harvard admissions officers come up with such measurements? Makes no sense to me.

Anyway, Harvard and other very selective schools take into account ethnicity among many other factors in putting together a first-year class. The admissions process at elite institutions has to be complicated as the schools strive for diversity so that their schools are at least marginally representative of America. For the courts and other parts of government to try to micromanage the process, especially at private institutions, is inappropriate.

This issue is particularly resonant in New England, with so many highly selective schools, most famously four (Harvard, Yale, Brown and Dartmouth) of the eight Ivy League schools and MIT. Ed Blum, the lawsuit’s originator, was previously involved in challenging the University of Texas’s affirmative-action program. Blum is a right-wing zealot whose efforts would restore what has in effect been white privilege to the admissions process.

Charles Desmond/Thomas C. Jorling/Kier Wachterhauser: How Harvard and other rich institutions can help save our planet

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Nonprofit institutions with large endowments have been facing challenges from various stakeholders contesting the management of their investment portfolios. While these challenges are most commonly associated with institutions of higher education, pension funds and private foundations will increasingly face similar challenges regarding how the management of their endowments affects socially important policies. Together, these endowments represent hundreds of billions of dollars, and the market power they possess is very substantial.

In the case of higher education, students, faculty and some alumni are pressing these institutions to divest of their holdings in fossil fuel-based companies. These include coal, petroleum and, in some cases, natural gas companies. This advocacy is based upon an overall societal objective to decarbonize our energy system in order to hold greenhouse gas emissions at levels believed to be necessary to prevent an increase in global temperatures above 1.5°C. For above this level, there is widespread consensus in the scientific community that the climate will change in ways that will threaten the ability of the life-supporting biosphere to sustain the human population, which that will grow to something on the order of 10 billion by 2050. The threats from climate change are wide-ranging, from droughts and extreme storms to sea level rise and ocean acidification to migration of infectious diseases and rapid species extinction.

The challenge of climate change is real and the nonprofit institutions that manage vast portfolios must examine how their substantial investments affect the social, economic and environmental well-being of the human community. Simply put, the trustees of these major nonprofit endowments must examine the contribution to human well-being they make with the explicit choices in the composition of their portfolios.

Certainly divesting in carbon-based corporations is one avenue to consider. It is, however, our proposal that a positive investment strategy is a much more effective way to drive the message that climate change is real and requires action by nonprofit organizations who sit on large amounts of capital.

Thus, we propose, as a start, that nonprofit organizations with endowments greater than $1 billion commit to investing 10% of their endowment in corporations whose primary business activity is building and operating alternative energy systems based upon the endless supply of the sun’s energy and the wind. These alternative energy systems would include photovoltaic electric generation and associated energy storage technology, especially batteries.

The power of this investment strategy is immense. Consider the impact of a 10% investment from 100 institutions with endowments greater than a billion. At a minimum, this would produce $10 billion. Harvard alone would produce more than $4 billion. Investments of this scale would take this nation a long way toward decarbonization. More specifically, these investments would replace fossil fuel generation of electricity with the concomitant result that portfolio managers would cease to make any investments in fossil fuel companies. Thus, the proposed strategy would also accomplish the objectives of divestment.

And these investments are competitive. Investments in wind and solar projects are now returning 6% to 10%, which is fully in line with the range of investment objectives that trustees of nonprofits instruct portfolio managers to achieve.

Climate change represents a serious threat to the well-being of the human community. Leaders of nonprofit organizations cannot in good conscience watch this threat unfold as if it is someone else’s responsibility. It is also our hope that the managers of nonprofit funds in this country will set the example for all to follow, regardless of industry. It is the responsibility of all of us.

If you are managing massive amounts of capital and can achieve competitive rates of return by investing in alternative energy technologies that will help protect the life-supporting biosphere, the choice appears clear: Act Now!

Charles Desmond is CEO of Inversant, the largest parent-centered children’s saving account initiative in Massachusetts. He is past chair of the Massachusetts Board of Higher Education and was a higher education policy adviser to former Gov. Deval Patrick. Since 2011, he has served as a NEBHE senior fellow. Thomas C. Jorling is former CEO of the ecosystem nonprofit NEON Inc., former VP for Environmental Affairs at International Paper Co., former commissioner of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, and former professor and director of the Center for Environmental Studies at Williams College. Kier Wachterhauser is a partner at the law firm of Murphy, Hesse, Toomey & Lehane, LLP, in Quincy, Mass., where he specializes in labor and employment law, legal compliance and governance, and litigation.