Llewellyn King's Journal: Thank God for the Gulf Stream; joys of cruising; novel-adaption angst

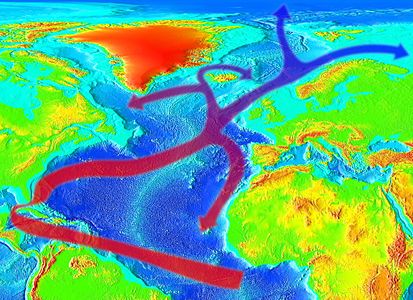

The Gulf Stream system.

COPENHAGEN

Whenever I stray from the East Coast of the United States, I’m reminded of the debt we owe to the Gulf Stream. Malibu, Calif. may be thick with Hollywood stars, but the water is damned cold. Always. I can tell you I’ve tried swimming there often and it is, by the standards of southern New England’s summers, cold. Really, for all the beauty of the West Coast, you have to travel as far south as San Diego to enjoy a dip, which might remind you of the waters of Cape Cod in July.

Lest you didn’t know, that’s why the number of pleasure boats in Seattle is said to be the highest on a per-capita basis in the nation. When it’s too cold to get in the water, get on it.

The Gulf Stream divides as it goes north and sends one branch to Africa and one to Europe, known as the Atlantic Drift. There’s some argument about how much the Atlantic Drift affects the climate of Europe. My empirical, unscientific observation is that it’s a big player and Europe and America would both be devastated with climate change if the Gulf Stream were to cease to flow or change course – a possibility with global warming.

It’s because of this great benevolent current, that there are palm trees on the coast of Cornwall and Devon in the west of England as well as in Ireland and Scotland. In those locations, they are small stunted things, in no way like their robust relatives in Florida. But they’re palm trees. And I’ve inspected some.

About Cruising, the New International Norm

I looked down my proboscis for years when anyone mentioned cruising. I also had harsh things to say about it.

Well, for a decade and a half, I’ve been dining on my words. I took a cruise with my wife, Linda Gasparello, that changed everything back in the early 1990s. We cruised mostly in the Black and Aegean seas -- and it was actually the best cruise we’ve ever taken.

It started our cruise contagion; we’ve cruised far and wide ever since. We’ve even journeyed briefly and enjoyably from Boston to Nova Scotia, but nothing equaled that first cruise. The ship wasn’t too big and the crew -- mostly Greeks on the catering side of things -- were marvelous.

The thing about cruising is the shore stops and tours. That first cruise took us from Athens to Yalta, Odessa, Constantia, Istanbul, Kusadasi, Mykonos, Patras and set us down in Venice. We learned – and this is the thing about cruising -- that it's wonderful because the hotel goes with you and the shore trips are usually well worth taking. That’s the kernel of what it’s about for us; not the food (too much, but good enough), nor the shows (Las Vegas lite), but the floating accommodation and shore excursions.

In 2015, just before Christmas, we cruised around Cape Horn. Amazing. It astounds me that rounding the Horn, where so many mariners perished, can be accomplished in a luxury liner. The shore trips in Argentine and Chilean Patagonia are worth running the credit cards up to the limit to do.

Linda and I have just been at it again. Capriciously, we decided that it was time to cruise the Baltic and see the jewel in its crown, St. Petersburg.

For me, it was a third visit and was Linda’s first. I knew it wouldn’t disappoint and it didn’t. If it isn’t on your bucket list, write it down right now. Then go.

If you get there by water, so much the better because the cruise companies deal with the hassles , and traveling in Russia can be a big hassle, from getting a visa to finding a hotel that doesn’t look like it’s an incubator for social diseases.

So many nationalities now cruise that it’s a new universal cultural norm, like pizza and Coca-Cola.

What’s Wrong with England and Australia for Novel Adaptations?

Paula Hawkins’s The Girl on the Train was a great read; an original story with an original kind of heroine: she has a drinking problem. Also, it's set in England and depends on English train commuting habits, not American. But when it was turned into a movie, it was mysteriously set in New York and the English actress, Emily Blunt, was the heroine.

Now there's a seven-part miniseries made by HBO and starring Sharon Stone and Reece Witherspoon of the splendid Liane Moriarty novel Big Little Lies. I haven’t seen it yet, but the thing is that Moriarty is Australian and her novels, excellent writer that she is, are set in suburban Australia. One of the considerable joys of reading Moriarty is that you forget that the novels are Australian: The struggles of school playgrounds and other aspects of middle-class suburbia are apparently universal.

The makers of the Big Little Lies the miniseries, which has gotten rave reviews, chose to relocate it to Monterey, Calif. Why? Maybe they thought a dash of Oz would be too hard for us to understand.

Oddly, Monterey is not typical of America’s suburbs either. Maybe, also, the series producers forgot that star Nicole Kidman is an Australian. Confusing.

Llewellyn King ( llewellynking1@gmail.com), is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a frequent contributor to New England Diary.

Tim Faulkner: Projected sea-level rise looks scarier

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A stitch in time saves nine. A cat has nine lives. Baseball legend Ted Williams wore No. 9. Unfortunately for Rhode Island, nine is also the new number for the feet of projected sea-level rise.

Just a few years ago, the upper estimate for sea-level rise was 3 feet. More recently, it was 6.6 feet. But a recent assessment by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projects sea-level rise to increase in Rhode Island by 9 feet, 10 inches by 2100.

“To put in perspective we’ve had 10 inches (of sea-level rise) during the last 90 years. We’re about to have 10 feet in the next 80 years,” said Grover Fugate, executive director of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC).

Fugate made the remarks during a recent environmental business roundtable featuring the state’s top energy and environment officials: Fugate; Janet Coit, executive director of the Department of Environmental Management; and Carol Grant, commissioner of the Office of Energy Resources.

Coit and Grant highlighted the positive trends in Rhode Island's “green economy,” such as growth in renewable energy and the fishing industry. Fugate spoke last and, referring to himself as the “Debbie Downer” of the meeting, straightaway delivered the bad news facing the state from climate change.

“I’ve been director here for 31 years and the numbers we are seeing are staggering to me,” Fugate said of the NOAA report. “The changes we are going to see to our shoreline are profound, dramatic, and there is going to be a lot of economic adjustment going forward."

The major upward revision in sea level-rise projections, he said, will be transformative to life in Rhode Island, particularly along the coastal region of Washington County and much of Bristol County and Warwick.

To drive the point home, Fugate showed photographs of severe beach erosion along Matunuck Beach in South Kingstown. The shoreline there has been eroding at a clip of 4 feet annually since the 1990s. Recently, the rate climbed to 8 feet a year. That level was calculated before NOAA released the latest projected increase in sea-level rise.

Higher seas, Fugate said, create a multiplier effect that intensifies coastal erosion and flooding. Tides and storm surges reach further inland. Climate change also produces stronger wind and rain events. Thus, a storm classified as a 50-year event can cause the same damage as a 100-year event, according to Fugate.

The recent NOAA report says the principal cause for higher seas is the melting of land-based ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. Since 2009, the region from Virginia north to the Canadian Maritime Provinces has experienced accelerated sea-level rise due to changing ocean currents in the Gulf Stream. NOAA expects that trend to continue.

According to the report, the impact of prolonged sea-level rise will be loss of life, damage to infrastructure and the built environment, permanent loss of land, ecological transformation of coastal wetlands and estuaries, and water-quality impairment.

Those impacts, Fugate said, are already here and being felt. He showed slides of storm drains flowing backwards and flooding parking lots during regular high tides, and buildings that are becoming islands. Coit noted that wetlands and marshes are essentially drowning in this higher water.

“The future is here now,” Fugate said. “It’s here and we are seeing profound changes.”

To combat climate change, coastal buildings are being elevated thanks to federal incentives. The CRMC also has permissive policies that allow for the rebuilding of sea walls damaged by these more forceful storms and accelerated erosion.

Several environmental engineers and municipal planners at the recent meeting raised questions about the need for policies and regulations to address threatened infrastructure, such as septic systems, utilities, and spoke about the risk of inland river flooding. Their queries suggested that the state is taking a piecemeal approach to a vast problem.

The environmental group Save The Bay has criticized an Army Corps of Engineers plan to provide funding to elevate homes along the Rhode Island coast from Westerly to Narragansett, R.I. Fugate said that plan has flaws, but endorses the concept as the best solution for protecting property owners.

Save The Bay, however, wants greater consideration given to migration away from the coast. Retreat from a receding shoreline, it argues, protects people, as well as the ecological health and resilience of the natural resource that defines the Ocean State.

“Are we going to elevate homes that can’t be reached because the roads are under water?” asked Topher Hamblett, Save The Bay’s policy director. “I think the state needs a long-term strategy about moving back from the coast.”

Hamblett portended that coastal retreat would greatly impact the real-estate market and present enormous challenges for policymakers and elected officials.

“But this is so big on so many levels that unless and until we start really seriously planning to move back out of harms way, we are going to inflict a lot of otherwise avoidable damage on ourselves,” Hamblett said.

Fugate and Coit said elevating buildings may not be the best option, but it's the only one currently with funding. If approved, it would provide about $60 million of federal relief money apportioned after Hurricane Sandy.

“Yes, the money would be better spent in another way,” Coit said. “Could we protect more land on the shore and in the flood plains? Could we help people move out all together through a buy-out program? Could we look at infrastructure that helps the whole public instead of the individual homeowner?”

Fugate said the problem is compounded by federal flood-insurance maps that created immense controversy in 2013, when the Federal Emergency Management Agency released inaccurate flood-zone maps. Those maps led to astronomically high insurance premiums for some and rampant confusion among others living on or near the water.

Fortunately, Fugate said, the CRMC and the University of Rhode Island have designed interactive maps forecasting the impacts of sea-level rise, coastal flooding and storm surge. The modeling behind those maps is helping remedy the flood-map problem. Nevertheless, Fugate encouraged anyone with property in a flood zone to buy flood insurance.

Coit said the state is in a good position to address sea-level rise and climate change by following the same model that led to the development of the Block Island Wind Farm. The Ocean Special Area Management Plan (Ocean SAMP) brought together federal, local and private stakeholders to craft a plan for mapping out public and private uses for offshore regions. CRMC is working on a similar Shoreline SAMP to address long-term coastal planning.

Coit said the state Executive Climate Change Coordinating Council (EC4) is already addressing comprehensive climate-change planning for the state. The EC4 recently released an assessment of Rhode Island's greenhouse gas-emissions reduction plan. It’s now scrutinizing flooding at wastewater treatment facilities, among other threats from climate change.

“I think we are in a good place for Rhode Island to really look holistically at a resiliency and adaptation plan that takes into account all of the issues,” Coit said.

Most of the EC4’s funding comes from the Environmental Protection Agency. CRMC gets half of its budget from the Department of Commerce. But Coit, Grant and Fugate say President Trump’s hostility toward climate change won’t curtail state planning efforts, much less the realities of sea-level rise and global warming.

While the NOAA report doesn’t offer its own solutions, it concludes that sea-level rise is unrelenting.

“Even if society sharply reduces emissions in the coming decades, sea level will most likely continue to rise for centuries,” according to NOAA.

Tim Faulkner writes for ecoRI News.

Tropical fish are arriving earlier in the summer in Narragansett Bay

A crevalle jack.

By TODD McLEISH, for ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When a tropical fish called a crevalle jack turned up this summer in the Narragansett Bay trawl survey, which the University of Rhode Island conducts weekly, it was the first time the species was detected in the more than 50 years that the survey has taken place.

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s (DEM) seine survey of fish in Rhode Island waters also captured a crevalle jack this year for the first time.

While it’s unusual that both institutions would capture a fish they had never recorded in the bay before, it’s not unusual that fish from the tropics are finding their way to the Ocean State. In fact, fish from Florida, the Bahamas and the Caribbean have been known to turn up in local waters in late summer every year for decades. But lately they’ve been showing up earlier in the season and in larger numbers, which is raising questions among those who pay attention to such things.

“There’s been a lot of speculation about how they get here,” said Jeremy Collie, the URI oceanography professor who manages the weekly trawl survey. “Most of them aren’t particularly good swimmers, so they probably didn’t swim here. They don’t say, ‘It’s August, so let’s go on vacation to New England.’ They’re not capable of long migrations.”

Instead, fish eggs and larvae and occasionally adult fish are believed to arrive in late summer on eddies of warm water that break from the Gulf Stream. Collie said they “probably hitch a ride” on sargassum weed or other bits of seaweed that the currents carry toward Narragansett Bay.

Most of these tropical species, including spotfin butterflyfish, damselfish, short bigeye, burrfish and several varieties of grouper, don’t survive long in the region. When the water begins to get cold in November, almost all perish.

“There’s no transport system to carry them back south, which is the reason they can’t get back where they came from,” Collie said.

While climate change and the warming of the oceans has been responsible for many unusual marine observations in recent years, that doesn’t appear to be the case with the annual arrival of tropical fish in local waters.

“Warming doesn’t really have an effect on it,” said Mark Hall, owner of Biomes Marine Biology Center in North Kingstown, which has been exhibiting locally caught tropical fish since it opened in 1989. “It’s just the way the Gulf Stream meanders and carries these fish our way.”

Ocean warming does appear to be affecting the timing of the arrival of the fish, however.

“Twenty years ago I wouldn’t bother trying to find tropicals until mid-August, but now we’re seeing them in July,” Hall said.

The good news is that none of these tropical species appear to be harming or out-competing the native marine life in Narragansett Bay.

“They arrive in July or August and are dead by November, so they’re just not here long enough to have an impact,” Hall said. “I can’t think of a single animal that’s having a negative effect.”

Collie agrees. “These strays are small and appear here in small numbers. The threat would come from wholesale movements of new species that can stay here for long periods. Tropicals aren’t a threat.”

For those interested in seeing some of the tropical species that are making their way to Rhode Island, visit Biomes in North Kingstown or Save The Bay’s Exploration Center and Aquarium at Easton’s Beach in Newport. Save The Bay just opened a new exhibit this month featuring tropical fish species collected locally by its staff, volunteers and partner organizations, including the Norman Bird Sanctuary and DEM. The exhibit, called The Bay of the Future, features a variety of what manager Adam Kovarsky calls Gulf Stream orphans.

“We want to spark people’s thought processes about the things that can happen from climate change,” he said. “While tropical strays have been showing up here forever and ever, there’s evidence that now they’re showing up in larger numbers and arriving earlier and surviving later. It’s not a problem now, but eventually they may stay year-round, and that could stress our local species.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Llewellyn King: Our destruction of life in the oceans

Memo to environmental activists: It’s the oceans, stupids.

This summer, hundreds of millions of people in the Northern Hemisphere will flock to beaches to swim, surf, wade, boat, fish, sunbathe, or even fall in love. To these revelers, the oceans are eternal -- as certain as the rising and setting of the sun, and a permanent bounty in an impermanent world.

But there is a rub: The oceans are living entities and they are in trouble. Much more trouble than the sun-seekers of summer can imagine.

Mark Spalding, president of The Ocean Foundation, says, “We are putting too much into the oceans and taking too much out.”

In short, that is what is happening. Whether deliberately or not, we are dumping stuff into the oceans at a horrifying rate and, in places, we are overfishing them.

But the No. 1 enemy of oceans is invisible: carbon.

Carbon is a huge threat, according to ocean champion Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I. The oceans are a great carbon sink, he explains, but they are reaching a carbon saturation point, and as so-called “deep carbon” resurfaces, it limits the oxygen in the water and destroys fish and marine life.

There is a 6,474-square-mile “dead zone” -- an area about the size of Connecticut with low to no oxygen -- in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Dead zones are appearing in oceans around the world because of excessive nutrient pollution (especially nitrogen and phosphorous) from agribusiness and sewage. Two great U.S. estuaries are in trouble: the Chesapeake Bay and Long Island Sound.

Warming in the North Atlantic is disturbing fish populations: Maine lobsters are migrating to Canada's cooler waters. Whitehouse and other Atlantic Coast legislators are concerned as they see fish resources disappearing, and other marine life threatened.

Colin Woodard, a reporter at The Portland (Maine) Press Herald, has detailed the pressures from climate change on fish stocks in the once bountiful Gulf of Maine. He first sounded the alarm 16 years ago in his book, Oceans End: Travels Through Endangered Seas, and now he says that things are worse.

The shallow seas, such as the Baltic and the Adriatic, are subject to “red tides” -- harmful algal booms, due to nutrient over-enrichment, that kill fish and make shellfish dangerous to consume.

Polluted waterways are a concern for Rio de Janeiro Olympic rowers and other athletes. Apparently, the word is: Don’t follow the girl from Ipanema into the water. The culprit is raw sewage, and the swelling Olympic crowds will only worsen the situation.

My appeal to the environmental community is this: If you are worried about the air, concentrate on the oceans. It is hard to explain greenhouse gases to a public that is distrustful, or fears the economic impact of reducing fossil-fuel consumption. If I lived in a West Virginia hollow, and the only work was coal mining, you bet I would be a climate denier.

The oceans are easier to understand. You can explain that the sea levels are rising; that it is possible for life-sustaining currents, such as the Gulf Stream, to stop or reverse course; and you can point to the ways seemingly innocent actions, or those thought of as virtuous (like hefting around spring water in plastic bottles) have harmful effects.

Plastic is a big problem. Great gyres of plastic, hundreds of miles long, are floating in the Pacific. Flip-flops washed into the ocean in Asia are piling up on beaches in Africa. Fish are ingesting microplastic particles – and you will ingest this plastic when you tuck into your fish and chips. Sea birds and dolphins get tangled in the plastic harnesses we put on six-packs of beer and soft drinks. They die horrible deaths. Sunscreen is lethal to coral.

It is hard to explain how carbon, methane and ozone in the atmosphere cause the Earth to heat up. It is easier, I am telling my environmentalist friends, to understand that we will not be able to swim in the oceans.

I have met climate deniers, but I have never run into an ocean denier. Enjoy the beach this summer.

Llewellyn King, executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, is a longtime publisher, editor, columnist and international business consultant. This piece first ran on InsideSources.

Gulf Stream feeling

"Storm Lifting'' (oil on panel), by MARTHA STONE, in her show "Atmospheric Landscapes,'' at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, May 1-29.

April 29, 2o14

This morning had that pleasant wet feel that comes before a southeast rainstorm -- almost a breath of the tropics that reminds us of how close the Gulf Stream is.

A very agreeable effect until I realized that the basement might flood in the next couple of days.

And the wind and the rain might soon strip off the blossoms from the flowering trees, whose show is so brief.

rwhitcomb51@gmail.com

January thaw

Jan. 25, 2014 A windy, mild and sweetly melancholic day with scudding clouds from the southwest. Snow and ice are melting without man-made stimulants. Once again I'm rather surprised and pleased by how the light is brighter in late January than even just a couple of weeks before, and by the power of even the winter sun to quickly heat us in sheltered places. Our unheated but glassed-in sleeping porch, which faces the south, gets up to 75 even when it's 15 outside. We use the space to heat the adjoining bedroom by day.

We New Englanders could do a lot more with passive solar heating. It's not as if we're that far north; we're at the latitude of Portugal.

One nice thing about aging is that while the cold itself is harder to take, especially the windy chill of Northeast coastal cities, you're ever more aware of how fast time goes -- it will be spring very soon. And while it has seemed recently that we're living on Hudson's Bay, actually we're much closer to the Gulf Stream.

In New England, more than in most places, we have the weather to help mark off sections of our lives, as an aide-memoire, and that's handy. Now we have the predictable "January thaw,'' which, though this one will be very brief, reminds us that our weather won't really be paralyzed by the likes of "polar vortexes'' or other such Weather Channel monsters. By the way, California is having record heat and drought. And Alaska has been pretty warm for, well, Alaska.

Scientists differ on why the rise in temperatures associated with the "January thaw' ' tends to happen in late January rather than in early February, which would seem to make more sense. In any case, I'm more vulnerable to the sadness from lack of light than from the cold. And the light is moving in the right direction.

comment via rwhitcomb51@gmail.com