Karen Gross: About those 'certificates of failure'

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The news is filled with stories about the admissions scandals at elite colleges and universities. And recently, some of the wrongdoers have pled guilty and await punishment. Apparently, prosecutors are seeking jail time. Apart from jail time, I have already suggested approaches to punishment that involve fines that go into a cy pres fund to be redistributed to small non-elite colleges and their students. Ironically (or not), the fake charity to which these parents “donated” was intended to serve low-income kids. Hey, make that really happen … and legally.

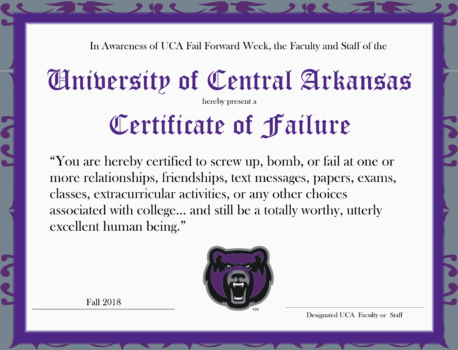

At the same time, there have been articles about the competitiveness of elite colleges and universities and the need to provide courses or partial courses or seminars in failure. The idea is legitimizing failure; it happens to everyone after all. But, since some college students have never experienced failure (see above), the colleges need to include instruction on how to fail. And some even provide “certificates of failure’’ at the beginning or end of the courses. (See image above.)

One of the pre-course certificates is issued, I am embarrassed to say, by my alma mater, Smith College. It is provided before the seminar begins with the suggestion that it be displayed proudly. The certificate provides, in part,

“You are hereby authorized to screw up, bomb or fail at one or more relationships, hookups, friendships, texts, exams, extracurriculars or any other choices associated with college … and still be a totally worthy, utterly excellent human.”

Apparently, students (at least those cited in the article about this in the New York Times) are delighted to hang these words in their dorm room. A recent article in The Washington Post shared similar initiatives, with some institutions replacing the word “failure” with “grit training” or “resiliency education,” although the certificates awarded for failure were noted.

I have no idea who invented this idea of certificates of failure for college students. Was it a psychology professor or a student-life professional or some consultant? Was it an expert in parent-child development? Answer that question, please.

From my perspective, this whole “accept” failure movement strikes me as what we term in other contexts “a first world problem.” In other words, learning about and dealing with failure is a problem for some students attending some elite colleges in America, where they suddenly get a low grade or struggle for the first time in their academic and personal lives.

From my experience in education, spanning early childhood education through adult education, I see the opposite experience among low-income, first-generation, minority, ethnically diverse and immigrant students. Many of these students experience failure early and often. In their schools, they are often, directly or indirectly, signaled: “You can’t make it.” Some are deprived access to gifted programs or AP courses. Surely they are not getting the level of tutoring that the wealthy can afford. There are assumptions, acknowledged or not, as to who progresses and where in education—from elementary school programs to elite public selective high schools to elite colleges (or any college actually). Just peruse the Pell Grant numbers of enrolled students at elite colleges (although the numbers are increasing).

I can’t count the number of students at Southern Vermont College (SVC), which is sadly failing now under current leadership and set to close unless miraculously saved (something for which I have been fighting), who said to me “I was told I was not college material.” Talk about not needing a certificate of failure. And many of the students we accepted back then at SVC had profiles that would have suggested that college was not in their future, let alone graduation. Indeed, the SVC Mountaineer Scholar Program, remarkable in so many respects though undermined of late sadly through mission drift at SVC, aimed to enroll students most thought would “never make it” in higher education. Some had projected graduation rates of under 9%; they too graduated.

There are many reasons that students have failed along the educational pipeline. Poor schools, poor teachers, fiscally underfunded schools, lack of parental support (or other adult support), cultural expectations and norms including few or no individuals believing in success. If you want to see this, view the movie Raising Bertie or the movie STEP. Surrounded by failure of every sort from food scarcity to parental absence, incarceration and addiction to homelessness, many of today’s college students have not experienced success. They have lived lives filled with failures.

These students don’t need lessons in failure; they need lessons in success and their capacity—remarkable capacity—to succeed.

I would add that trauma, a topic about which I have been writing regularly, has been a large contributor to low student expectations and misunderstanding of student capacities. Indeed, we know that trauma has many cognitive effects on student learning, and it is often mistaken for other student shortcomings—when actually the students did not ask for the trauma and had no choice in being on the receiving end. Children who have been traumatized and are not in trauma-sensitive environments with tools to defuse the autonomic nervous system can feel the effects for a lifetime. Trauma’s aftermath can make you feel like a failure when you are anything but. You are a survivor. But trauma and its impacts don’t disappear. Reflect on the recent suicides a year after Parkland and several years after Sandy Hook. Tragic.

Most of us don’t need certificates of failure. We have failed. We have experienced lowered expectations. We know what it is like not to succeed and to watch others around us fail with regularity.

The focus on “certificates of failure” makes me ill actually. It applies to such a narrow segment of college students. Why is it that we can’t pay more attention to the vast majority of students and put our time, our energy, our money and our focus on their successes—hard-fought successes—in a world that dealt them failure? Yet again, we focus all our attention in the media and elsewhere on the elite as if that is all that matters and as if that is somehow representative of the vast majority of the population.

So, with the elite parents bribing and certificates of failure to offset lots of success and soft shells in some children raised to always feel good, let’s shift gears immediately. Let’s help non-elite colleges and students across the educational landscape for whom failure has been a constant companion. We don’t need a certificate of failure. It is evident in lives being lived. Instead, we need folks who believe in our success.

Karen Gross is senior counsel with Finn Partners, former president of Southern Vermont College and author of Breakaway Learners: Strategies for Post-Secondary Success with At-Risk Students.

Karen Gross: Ranking colleges by percentage of students who vote

Registering young voters during the March for Our Lives in Boston on March 24.

From the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The recent March for Our Lives at hundreds of locations around the globe rattled my cage, particularly as I stood in the middle of hundreds of thousands of protesters in Washington, D.C. Had we finally found a way to increase activism, to get more and more people of all ages and stages involved in the well-being of their communities?

As I listened to the young speakers both over the loudspeakers and later on television, I wondered: Have the voices of high schoolers (and some even younger students) been ignited such that their fire will expand? These young people from Parkland, Fla., and beyond, seem capable of spreading their energy, their eloquence and their belief that “enough is enough” in terms of gun violence.

Here’s what worries me and I assume others: Can the efforts of these students to change gun laws to increase school safety be sustained?

Some movements falter; others have stickiness. As a product of the ‘60s, I experienced the rigor of our positions on civil rights and the Vietnam War and the need for women’s voices to be heard. We achieved some remarkable successes, though our work is still far from done.

All of this brings me to college campuses and my concerns about levels of student activism. Yes, there have been more protests in the past 24 months, spurred in part by efforts to eradicate sexual harassment and abuse. But are students actually engaging in the political process that other fundamental way: by exercising their right to vote?

Yes, many campuses have voter registration drives. Yes, there are personnel on some campuses to help students get absentee ballots. Yes, there are some young people running for office, particularly local officers. Yes, there seem to be more students interested in participating in politics.

But....

The percentage of college student voting, though rising in recent years, is below 50 percent. Data from the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service, at Tufts University, tells a story of which we should not be proud if we believe that our democracy depends on citizens’ exercising their right to vote.

The percentage of white students who vote increased between 2012 and 2016, as did the percentage of Hispanic and Asian students; the percentage of black students decreased. But more important than the increases/decreases per se are the actual percentages of students’ voting in any given year. In 2016, 53 percent of white students, 50 percent of black students, 46 percent of Hispanic students and 31 percent of Asian students voted. Yipes.

Who votes?

Ponder these statistics: 53 percent of students in social sciences voted, compared with 44 percent of students in STEM disciplines. Students at public four-year institutions (50 percent) vote more frequently than students at community colleges (46 percent) and private four-year colleges (47 percent). Voting at women’s colleges and minority-serving institutions colleges exceeded percentages at Hispanic-serving institutions. Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) had the lowest percentage—a troubling statistic for many reasons.

Notably, the Tisch study does not include data for the percentage of voting by students at for-profit institutions.

Whether the data are complete and whether they fully capture all student voting (the data focus of the study is on presidential elections not other federal elections or state or local elections), we can still observe that there are differences in student voting rates at different colleges and universities.

What this means is that, if the data were actually available, we could compare and contrast colleges/universities on the basis of student voting rates. Indeed, students particularly interested in civic engagement and activism would be able to see which colleges/universities they were considering had very high voting rates and which had very low rates.

Now, we have many ways of rating and ranking colleges and universities. And there has been considerable debate about the quality of the existing measures used to compare one college/university to another. Assessment is a quagmire. For example, institutions with large endowments and higher admissions selectivity have higher rankings as calculated by US News than those with small endowments that also enroll high numbers of their applicants. Note that none of these are measures of educational quality unless one wants to say that big endowments and enrollment selectivity are surrogates for quality measures—assumptions I think are at once wrong and misguided.

Ratings (ostensibly different from rankings) are prepared by the U.S. Department of Education through the College Scorecard, and these data are also flawed on a myriad of levels. For starters, they look at retention and graduation rates based on first year-first time students, meaning that transfer students and their successes are not measured by the institutions that receive them or from which they departed. Odd, isn’t it?

We could wish for a day when all rankings/ratings are eliminated. But perhaps in the meantime, here’s one measure that could have meaning to a newly engaged youth population emboldened to make change and perhaps their parents and teachers: a comparison of voting rates among enrolled college/university students. I am not the first to reference the possibility of ratings based on voting rates (among other variables of civic engagement). But such ideas have not been embraced yet systematically.

For example, Northwestern University reportedly introduced voting during orientation in 2011, and voting by their enrolled students in presidential elections increased from 49 percent in 2012 to 64 percent in 2016. At East Tennessee State University, after concerted institutional and student efforts, voting in presidential elections by students increased to 47 percent from 39 percent. True, the numbers are still low but not as low as they were.

With the signs encouraging voting and political muscle at the March for Our Lives and the growing activism of high school students today, it seems that voting rates at colleges would matter to today’s K-12 students. If they had a choice of colleges—say among Harvard, Haverford, Hampton and University of Hawaii—how would they choose? Location? Price? Guidebook rankings? Programmatic offerings? Size? Reputation?

What if the voting rates among these colleges differed dramatically (a set of statistics we do not know at present across institutions)?

Local elections matter, too

If one were to create a ranking/rating system of value to students and their families, we would want to look at more than federal election voting levels. Local and state voting matter; these elections reflect how communities govern and function, and in some of these elections, there are votes that affect students and justice directly: school board elections and election of judges. The latter two elections affect how our schools function (and the dollars allocated to education) and how legal disputes, including those related to protests, permitting, free speech, civil rights and voting rights, are resolved. Election of state and federal representatives matters too because these individuals can serve on education and budget committees.

Keep in mind, too, that in some states, the outcomes of local and state elections are decided by a small number of votes, given low voter turnout.

And if one wants proof that a vote matters (an issue for some who see no value to voting), just remember Bush v. Gore, in 2000, and "hanging chads." Even if students are unaware of that electoral debacle given their ages, it is a part of history as to which much has been and should be read. For me, it is about more than politics; it is a story about our civic responsibility and how the right to have one’s vote count got trampled.

For college students, there is also the thorny issue of where they can, do and are allowed to vote and this problem should not be underestimated. And it cannot be dismissed by saying: Just vote; it does not matter where. That is not even true in presidential elections where a small number of votes can move the Electoral College one way or another.

Sadly, I have had experience with the difficulty students experience registering to vote in the town where they go to college, live, eat, study and work. I remember distinctly verbally sparring with the late and revered town clerk about the propriety of students registering to vote where they go to college. It was not pretty and was overheard by many. The counter-argument given: These students are not a part of our community; they are only here for a short period; they do not have the community interests are heart. State authorities had to be contacted.

Really? There are many people who move in and out of communities—who are not students. Even longstanding residents often do not vote; they use the schools; they work outside the locale. The students, on the other hand, are often engaged in the community, most especially those who work to help pay for their education; they perform internships in local businesses and or clinical rotations in local hospitals.

I wish I had known about the Supreme Court decision of Symm v. United States (1979), and, yes, I was a law professor for decades and clearly not cognizant of voting rights.

Improve voting rates

There are concrete steps colleges and outside organizations can take to improve voting by students on college campuses. There can be voting drives. There can be debates held on campus. There can be courses dealing with electoral outcomes and even “pop-up” courses for credit that focus on particular election issues that are timely and pressing. There can be messaging about the role of voting in a democracy and the fights in other nations for the right to vote. There can be campus readings; there can be campus speakers; there can be systematic voter registration drives.

As the demography of America’s students changes to include more “non-trads” (students over age 24) and minority students, the power of the vote is all the more important so that the voices of the many are heard. And there are efforts that could be instituted legally to ease voter registration and the location where voters can rightly vote. Misinformation is, unfortunately, often used to ban voting by students. The above-referenced town clerk was dispensing bad information in my view. Or let’s say, he discouraged local registration with such rigor that students were left discouraged from pressing forward.

A rating of “voting” percentages broadly defined speaks volumes about an institution. It bespeaks campus culture, campus involvement, campus priorities. It sends a message about how activism and political activity will be received and handled and supported. In today’s world, that’s a pretty good reflection of citizenship and the role of educational institutions in preparing the leaders of tomorrow. Surely voting percentages are more important than the size of a college’s endowment or other indicators we currently use to measure the quality of colleges.

Can you imagine students, parents and teachers saying: “Before we decide on the best schools to which to apply, let’s look at their voter rating.” It could happen. And it should happen.

Voting. What is more important to the success of our democratic processes and how important is it to teach our future leaders to take their social responsibility to vote seriously? Not much except perhaps their personal health, their mental well-being, their love of learning and their openness to change and problem-solving.

Karen Gross is senior counsel with Finn Partners, former president of Southern Vermont College and author of Breakaway Learners: Strategies for Post-Secondary Success with At-Risk Students.