David Warsh: Dorchester's weekly paper plows on through the decades

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Rupert Murdoch is stepping down as chairman of Fox and News Corp, having built the little Australian newspaper he inherited at the age of 21 (The News of Adelaide, circulation 75,000) into a global multi-media complex of enormous political influence. He is to be succeeded by his elder son.

Myself, I have been preoccupied recently with the saga of The Dorchester Reporter, which celebrated the 40th anniversary of its founding with an ebullient party in Boston on Sept. 14.

That “every banker has one good idea” is an old-time industry joke. Ed Forry’s good idea was to get out of the business. In 1983, at age 39, with banking deregulation accelerating, he quit his $24,000-a-year job as a savings bank executive to found a community newspaper in Boston’s largest neighborhood. Dorchester was then recovering from a decade of white flight to the suburbs,

Forry had some experience to start with: confirmed in St. Gregory’s Parish, he had graduated from Boston College High School and Boston College. As a community activist, he had written a column for the Dorchester Argus-Citizen, with which Forry had created a profitable yearbook business. His wife, Mary Casey Forry, would be an all-in partner. The couple had two young children and $5,000 in the bank.

The Reporter circulated monthly for several years. At first, advertising paid the way. The monthly went weekly, paid subscriptions were introduced, circulation grew. There were hard times. In 1993, as recession lingered, Forry laid off the entire staff of nine. Mary Forry died in 2004. By then, son Bill had joined the business, to become, eventually, executive editor and publisher. He married Linda Dorcena Forry, a Haitian-American who won election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 2005, then moved on to the state Senate, where she held a seat until 2018. For an account of those first 25 years, read the story by Boston Globe columnist Jack Thomas.

What is the business worth today? Decent livings for its eight fulltime staffers, paid gigs for its regular lineup of columnists and critics, and opportunities for interns and freelance writers. The paper has disproportionate political influence —-Boston Mayor Michelle Wu and U.S. Sen. Ed Markey spoke at the party — and retained earnings, and has considerably enhanced Dorchester pride.

xxx

In 1963, at the opposite end of the enterprise spectrum, a married couple of lawyers from Brooklyn saw promises in the California building boom and purchased the Golden West Savings and Loan Association in Oakland. In a go-go market of 1968, they made a public offering, Over the next 40 years, Herbert and Marion Sandler ran the most successful residential-mortgage lender in the country, until they sold the firm in 2006 at the top of the market for $24 billion to a North Carolina bank. Widely blamed – in their view unfairly – for the subprime housing-mortage crisis, they commenced a long-planned entry into the philanthropy business.

Among many other overtures, they called Paul Steiger, who for 16 years had been editor of The Wall Street Journal, which was just the being acquired by Rupert Murdoch. The result, in short order, was ProPublica, with an annual budget of $10 million, for the practice of WSJ-style investigative journalism.

Steiger hired as his successor Stephen Engleberg, an 18-year veteran of The New York Times. Effective fund-raising raising increased the annual budget to $40 million. So with a staff of a hundred or so well-seasoned journalists, ProPublica has established itself as the most successful of philanthropically endowed news organizations that have arisen among the ruins of the old advertising-supported metropolitan print press.

What’s the second-best nonprofit news organization? National Public Radio, at least in my view. And though it is reasonably well endowed, it has recently beginning a new fund-raising campaign. Lacking the same marriage of top newspaper cultures, its enterprise ventures in news are somewhat lower-key. And lacking undisputed foundational principles, it is susceptible to the regular political tempests that afflict Washington D.C.

xxx

Now back to Murdoch. How did he do it? Mostly by buying newspapers properties in down markets, then building them up experimentally instead of stripping them down. Fox News, which he founded in 1996, with former Richard Nixon pollster Roger Ailes, was a particular success; MySpace, an early competitor to Facebook, didn’t fair nearly as well.

Murdoch, 92, and in good health, has put his first-born son, Lachlan, in charge of all of the empire. But further struggles maybe in store. The mogul has three other children; they are entitled to equal shares under terms of his will. The conglomerate can be disassembled and shared out. But the conglomerate’s Wall Street Journal will probably power on.

That in turn leads to The Washington Post. When Donald Graham sold his family-controlled newspaper to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos for $250 million, in 2013, it was for far less than might have been offered by other bidders. Why was that? Consider that as one of the world’s richest men, Bezos possessed both the means and the moxie to restore one of America’s three leading newspapers to robust good health. Yet it can’t have escaped Graham’s attention, either, that Bezos has four children. Thus the Post’s independence will be preserved well into the future. That seems to have been a central aim of the public-spirited Graham.

Finally, that leads back to Boston. When the New York Times Co, sold The Boston Globe to Boston Red Sox owner John Henry, in 2012, for $70 million, having mismanaged the property for more than a decade, the direction of the paper itself fell to Henry’s wife, Linda, a native Bostonian. She has managed to keep it not just afloat, but interesting. It is profitable, she says, though print circulation continues to decline.

At a Globe conference on the new business last week, she spoke proudly of new bureaus in Rhode Island and New Hampshire. We’re not interested in becoming a national [paper],” she told listeners, “but as there’s been a decline in smaller regional places, we’re trying to fill that gap.”

In Dorchester, meanwhile, the money comes from putting newsprint on the front porch. The Dorchester Reporter probably out-influences the old Boston Herald, once owned by News Corp and now operated out of suburban Braintree by Media News Group, and, at least in municipal politics, often rivals The Globe itself.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Economicprincipals.com is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support Mr. Warsh’s work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

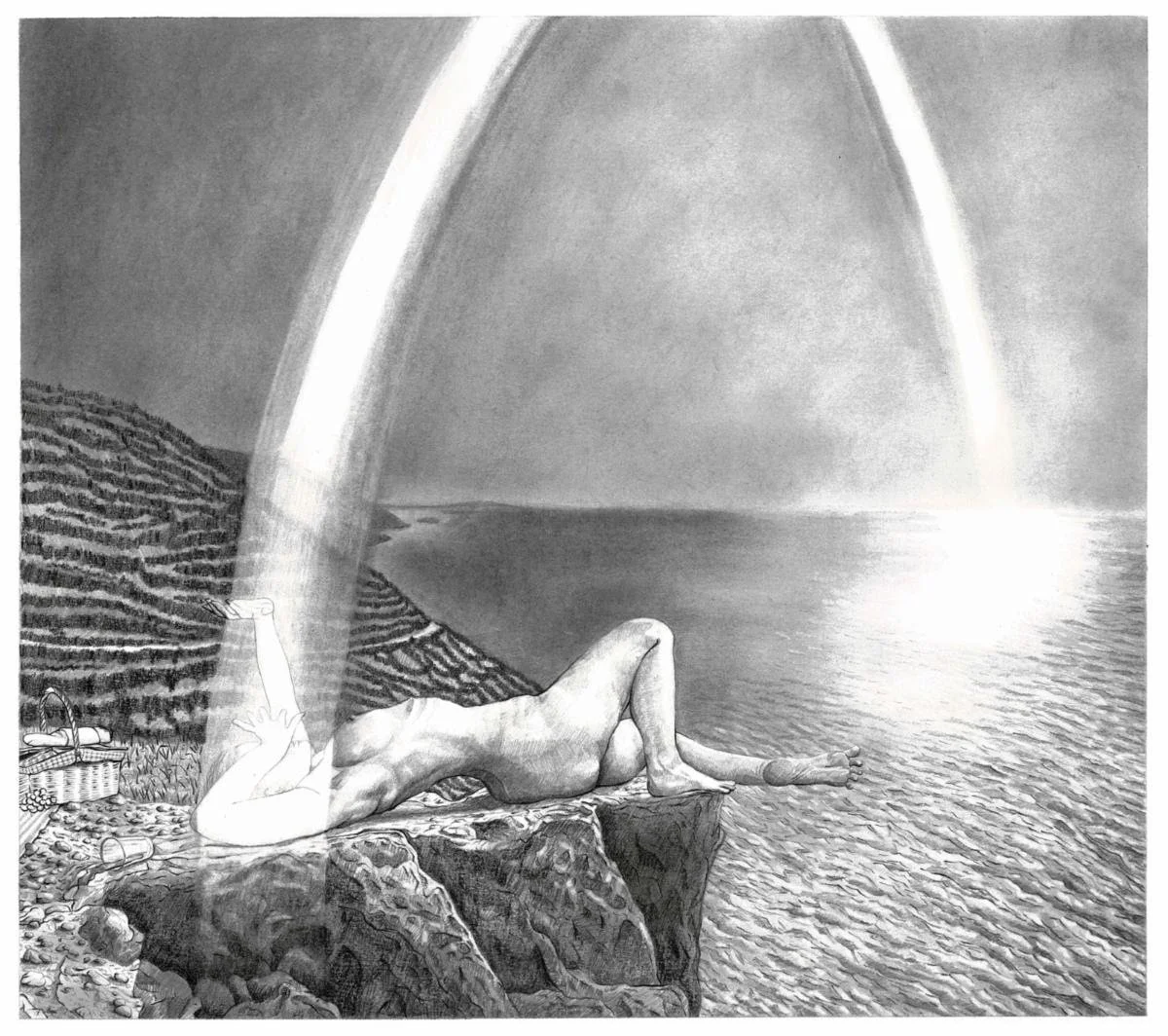

But don’t look down

‘‘Climb to the Rise’’ (oil on canvas), by Judith Brassard Brown, at Kingston Gallery, Boston.

Her artist statement:

‘The acts of making and viewing are opportunities to heal. While paintings may appear traditional at first glance, they do not recreate a specific location or event. Rather, each provides connections across boundaries of time or a captured moment, contrasts what we see with what we sense below the surface. Their qualities may activate our capacity to connect with others and with our own buried emotions. In recognizing what is compressed, that recognition may activate a corresponding release of psychic burden and an increase in joy.’’

She’s based in Boston’s Dorchester section.

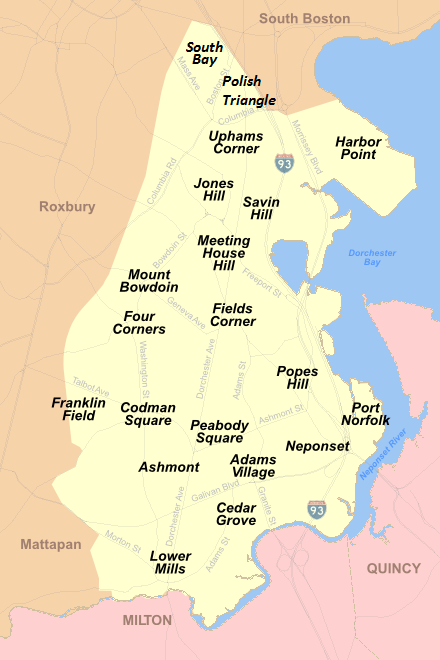

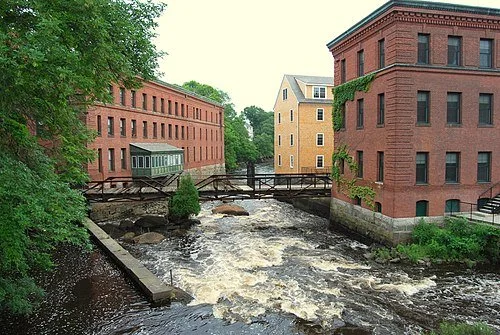

Neponset River at Lower Mills (2009). Dorchester on the left, Milton on the right (south) side of the river.

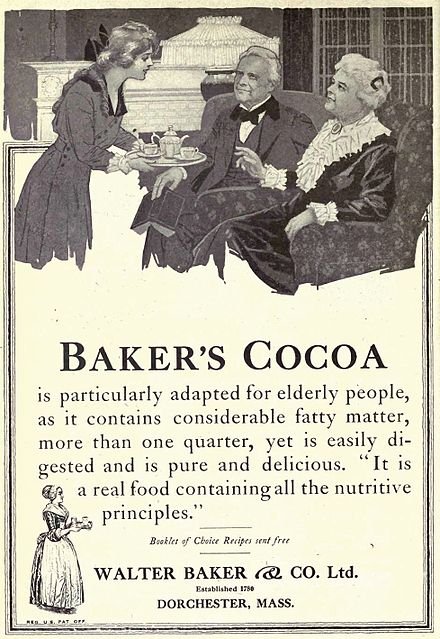

Baker's Cocoa Advertisement in Overland Monthly, in January 1919. The manufacture of chocolate had been introduced in the United States in 1765 by John Hannon and Dr. James Baker in Dorchester, then a separate town from Boston. The long-gone Walter Baker & Co. was based in Dorchester.

Chaseedaw Giles: What does it say about your Boston neighborhood if your grocery store isn’t great?

Not very healthy: A variety of Oreos line the shelves at the Stop & Shop at 460 Blue Hill Ave. in the Dorchester section of Boston.

— Photos by Chaseedaw Giles for Kaiser Health News

The Stop & Shop at 301 Centre St. in Boston’s heavily gentrified Jamaica Plain section features a large marketplace for natural and organic foods.

Though I grew up in Roxbury, “the heart of Black culture in Boston,” I now live in Los Angeles, where I typically shop for groceries at Whole Foods Market or Trader Joe’s. Their produce is fresh, green, abundant. Organic options beckon as you walk in the door.

So it gnawed at me, a Black woman, when I recently walked into a supermarket in a lower-income L.A. neighborhood and was greeted instead by an array of processed, high-sugar, high-sodium foods — often offered with a nice discount: Coca-Cola products, five 2-liter bottles for $5; sugary cereals, two for $4; boxed brownie and cake mixes, four for $5.

The pandemic had underlined long-standing health disparities of Black and brown communities. COVID had resulted in a 2.9-year decrease in life expectancy for Black Americans, compared with 1.2 years for white Americans. Research had consistently shown that among the underlying factors giving rise to those poor health statistics — high rates of diabetes and heart disease, for example — is poor diet, fueled by a lack of healthy food options in their neighborhoods.

“I could go into a supermarket, and I can tell everything about the people who live [in the area] based on what’s in their carts, based on what’s at eye level, what’s not at eye level,” said Phil Lempert, also known as the “Supermarket Guru.”

In retail, specific product placement — not just a store’s inventory — heavily influences a shopper’s experience. So shouldn’t responsible markets encourage shoppers to make better choices?

“There’s a lot of racism, to be honest, I think, behind these decisions, whether it’s unconscious or implicit,” said Andrea Richardson, a policy researcher focused on nutrition epidemiology at the Rand Corp. and professor at the Pardee Rand Graduate School. The presence of a supermarket in your neighborhood should signal that you aren’t living in a food desert, but, I wondered, if the supermarket isn’t guiding you toward more healthful food choices, you might as well be.

Chaseedaw and Lilie’s Shopping List

– Oat milk

– Lettuce

– Ezekiel bread

– Breakfast sausage (MorningStar)

– Fruit

– Cereal

– Cashew cheese

– Quinoa

– Snacks/chips

– Soda/juice

– Meat (fish)

– Mushrooms

So when I flew home for Thanksgiving, I enlisted my mother, Lilie — who always cared about her kids’ diets — to help with more research. I have vivid childhood memories of her scouring multiple grocery stores — often traveling to different parts of town — for the freshest ingredients when none were available close by. We set out one Sunday last fall to buy 12 items on a simple “healthy eating” shopping list at five locations of Stop & Shop, a supermarket chain with stores in a cross-section of Boston neighborhoods.

First the good news: We were able to find every item we wanted at each store. But, just as I’d experienced in L.A., healthy foods were easier to find in higher-income neighborhoods. In lower-income areas, junk food was more likely to be front and center.

At the Stop & Shop I recall from my childhood in Jamaica Plain, the food choices had become much more balanced, with a plentiful organic food section in the front of the store. My mom can now buy fresher greens locally.

But that likely in part reflects the gentrification that has taken place since I was a kid. Jamaica Plain now has a median income of almost $77,000 — though the poverty rate is 18.3 percent and the aroma of Dominican and Haitian patties still scented the air as we approached the entrance.

Our next two stops were in even fancier areas, Brookline (median income over $115,000) and Somerville — both green oases compared with many of Boston’s grittier neighborhoods.

At the Brookline location, each aisle started with low-fat, low-sugar choices like Crystal Light and V8, and the candy section was minuscule. In Somerville, the produce section was spacious, leaving plenty of room to browse the bins of guava and dragon fruit.

Our next Stop & Shop was in South Boston — a working-class, Irish Catholic community. It was strikingly different than our first three stops. The organic section consisted mostly of breakfast bars and cereals. The produce section positioned caramels, candied apples, and pumpkin-spice doughnuts in a bin alongside regular apples — at the bargain price of two packages for $3. The “International Foods” aisle sold everything you need for a very American Taco Tuesday, while a big part of this section was dedicated to Italian and Irish foods.

In the Grove Hall neighborhood in Dorchester — a predominantly Black neighborhood with a median income of $55,000 — the offerings were downright dispiriting.

Soda was displayed prominently near one entrance. And as we walked the aisles it seemed that many of the “sale” items were sugary soda products, chips, or cookies. This store had a dizzying array of snack food options, including 20 kinds of Oreos. And there wasn’t an organic food section at all.

The chain has been “doing a lot of work” to make sure that stores are “culturally relevant and [reflect] the demographics of the neighborhood,” said Jennifer Brogan, director of Stop & Shop’s corporate external communications and community relations.

How a store is stocked depends on size, product movement, shelf size, and a mixture of customer feedback and data. That data comes from companies like IRi, a research company, that provides consumer, shopper, and retail market intelligence and analyses.

Lempert, the “supermarket guru,” further explained that companies and brands pay retailers “promotional dollars” to put their goods “at eye level” or on sale, or make them available for consumers to sample.

But in making these largely commercial decisions, markets make it more difficult for people in low-income areas to eat healthfully, encouraging those with poor diets to continue the habits that landed them with diet-related illnesses.

“It has been well documented that junk-food companies spend significantly more money advertising in certain communities,” said Kelly LeBlanc, director of nutrition at Oldways, a Boston-based food and nutrition nonprofit. A 2019 report, for instance, found that junk-food advertising disproportionately targeted Black and Hispanic youth.

Stop & Shop has started to try to redress the inequity, with changes coming first to its Dorchester location, including an in-store dietitian. The Grove Hall store also sends out an ad circular that features promotional pricing on better-for-you items, which may include fish, vegetables, and fruit. It has joined the Fresh Connect food prescription program that allows participating doctors to prescribe to patients a prepaid Visa card that can be used to purchase fruits and vegetables.

Still, why not simply cut down on the soda and bewildering number of Oreos, I wondered. “I think our job is to give customers a choice,” Brogan said. “I also think we have a responsibility to help them make healthier choices.”

I’m glad my mom taught me how to make those choices early on.

Another thing I learned: There’s a whole science behind how supermarkets are organized, and depending on where you live, that could say a lot about the surrounding area. So the next time I think about moving, the first place I’m heading to is the local supermarket because, as Lempert told me, “going to that community grocery store is going to tell you about the neighborhood.”

Chaseedaw Giles is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Just me and my landscape

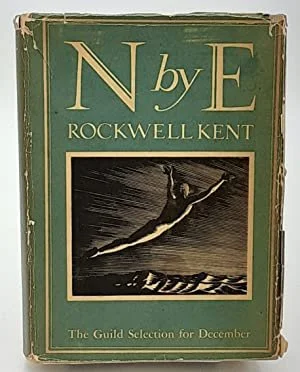

“Light” (graphite and charcoal on paper), by New York-based Catalina Viejo Lopez de Roda, in her show “Self Care’’, at HallSpace Contemporary Art Gallery, in Boston’s Dorchester section, starting Dec. 11. {Editor’s note: This reminds me of the work of Rockwell Kent.}

The gallery says: "Dealing with a persistent virus has instigated a new direction in Viejo’s work, with the central theme being Self Care. A single woman lives in isolation in each of her drawings, paintings and animations. These women inhabit wild environments and have developed a symbiotic relationship with the landscape."

Training by the Boston cops

“Growing up, I think I was arrested 20-odd times by the Boston police. The good news is that I've been able to use those experiences in a lot of my roles, and that has been a blessing.’’

— Mark Wahlberg (born in 1971). The movie actor and businessman was born and raised in Boston’s then mostly gritty Dorchester neighborhood, before gentrification moved in.

As repetitive as snow

"Snow Day,'' by Emily Berger, in the group show "Painting Is Not a Good Idea,'' at HallSpace, in the Dorchester section of Boston, through Jan. 7.

The gallery says that this show "invites viewers… to challenge views about what art should be and how art should be expressed. Guest curator Jo Ann Rothschild selected work from abstract painters Emily Berger, David Fratkin, Colleen Randall and Elizabeth Yamin. Though each artist works abstractly, their works are vastly different. Emily Berger, for her part, notes that the "paintings and drawings are based on a structure of repetitive and deliberate gesture that is intuitive but carefully considered."