Going medieval

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal 24.com

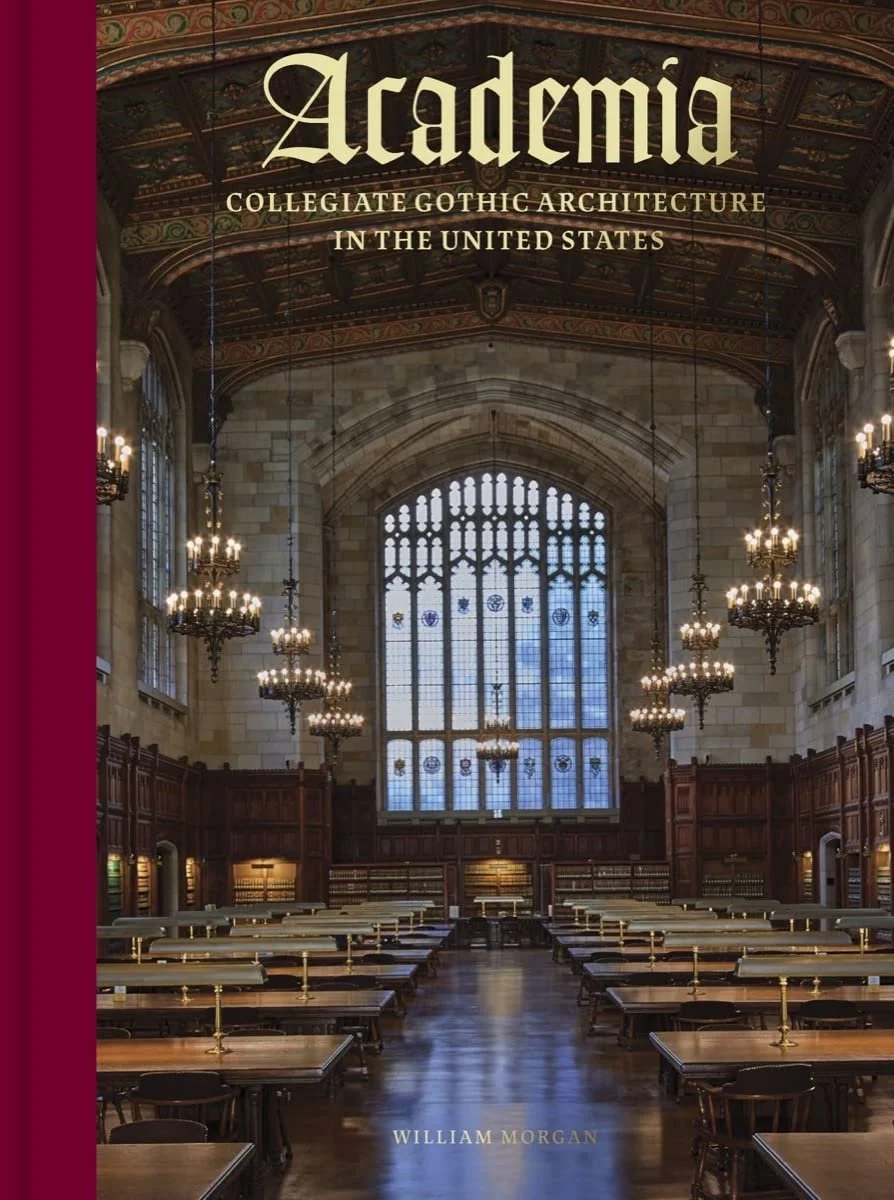

In reading William Morgan’s brilliantly written and gorgeously illustrated new book, Academia – Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, you might recall Winston Churchill’s famous line: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.’’

I thought of this looking back at an institution I attended, a then-all-boys boarding school in Connecticut called The Taft School, founded by Horace Taft, the brother of President William Howard Taft. Its mostly Collegiate Gothic buildings made some of us students feel we were in a hybrid of a medieval church and a fort. This, I think, encouraged a certain personal rigor and seriousness of purpose, amidst the usual adolescent cynicism and jokiness.

The blurb from the publisher (Abbeville Press) summarizes well the book:

"Academia provides the ultimate campus tour of Collegiate Gothic architecture across the United States, from Princeton and Yale to Duke and the University of Chicago. It tells the surprising story of how the Gothic style of Oxford {whose origins go back to 1096} and Cambridge {founded in 1209} was adapted and transformed in the United States, to lend an air of history to the country’s relatively young college and prep school campuses. And it shows how Collegiate Gothic architecture, which flourished between the Gilded Age and the Roaring Twenties {into the Thirties, too}, continues to define the popular image of the college campus today—and even inspire new construction.’’

The style originally reflected a certain Anglophilia embraced by some American nouveau riche as they accumulated fortunes in a rapidly expanding economy. Rich donors, and the institutional architects they got hired, wanted to create buildings evoking kind of elite, aristocratic culture at certain old Protestant colleges and universities and private boarding schools. (Many of the latter were modeled on English boarding schools catering to the aristocracy.) There was often a lot of snobbery involved. But the style spread to other institutions, too, including businesses and government offices, around the country.

Some of this included fantastical (to the point of silliness) ornamentation and instant aging of stonework to suggest the wear of centuries on what were brand-new buildings, perhaps most flamboyantly at Yale. Get out those gargoyles!

The nearest major Collegiate Gothic campus to Providence is the Jesuits’ beautiful Boston College in Chestnut Hill, just outside of Boston.

Some institutions mostly stuck with the simpler and cheaper Georgian brick style (in New England that includes even mega-rich Harvard and merely rich Dartmouth and Brown) but Collegiate Gothic was a huge thing for decades, and much of it was beautiful. Even today, architects are designing, sometimes ingeniously, new applications of the style.

This book is about much more than architecture. It’s also about personalities, many of them colorful, class, including social climbing, Western civilization, economics, materials, politics and many other things.

One of the book’s joys is Mr. Morgan’s footnotes, which besides adding to the understanding of the main text, are often very entertaining, sometimes even hilarious.

Gasson Hall, at Boston College, in the Chestnut Hill section of Newton, Mass., an example of high Collegiate Gothic architecture

— Photo by BCLicious

Massachusetts Hall at Harvard University, an example of the sort of Georgian Brick architecture that was the most common alternative on campuses to Collegiate Gothic.